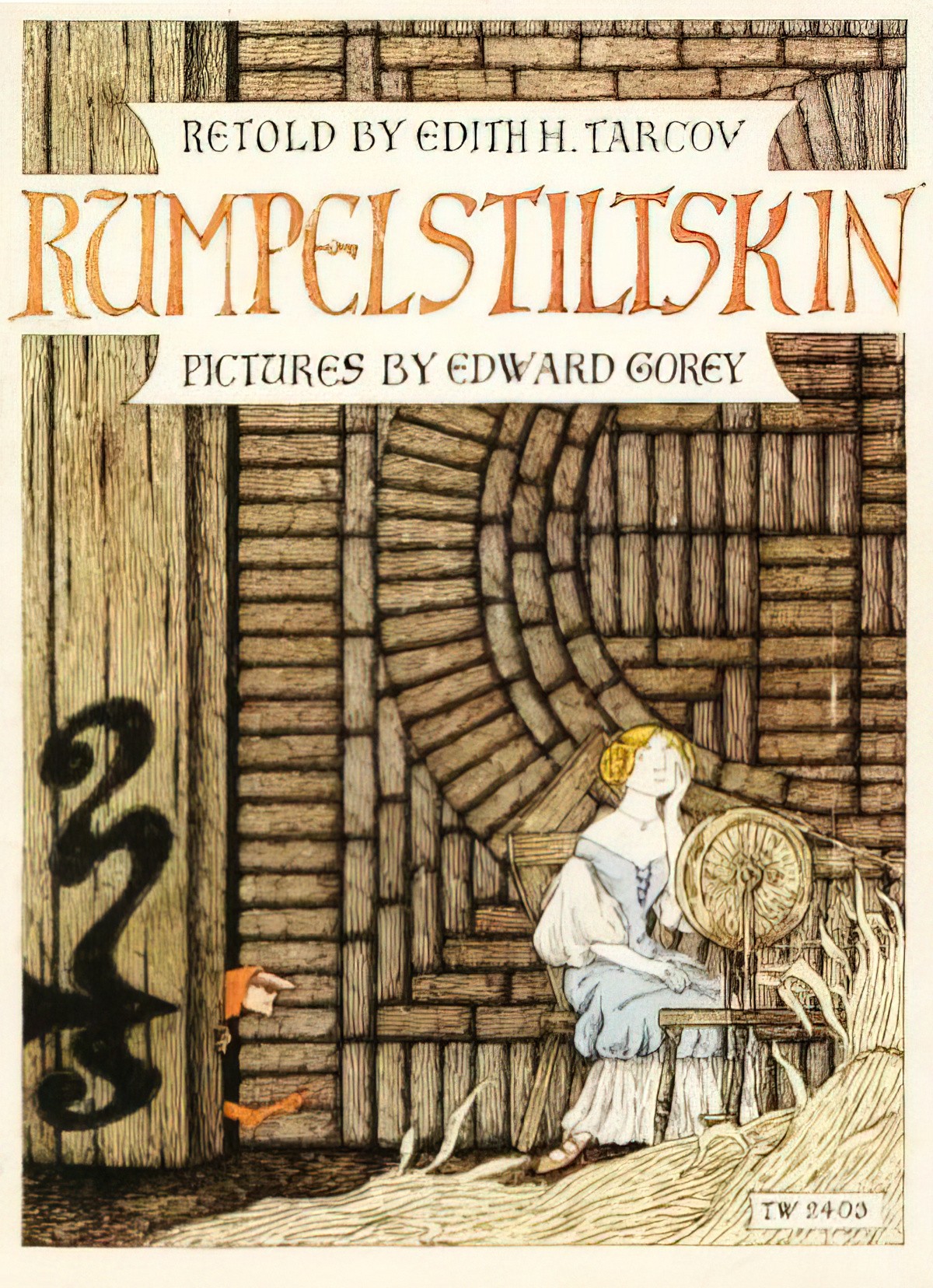

The tale of Rumpelstiltskin asks a moral question: Who is the worst of the three men? The lying father who gives away his own daughter, the greedy King who threatens death, or the proto-men’s rights activist dwarf? Or is it the daughter herself?

This is my all-time favourite fairy tale because it’s so twisted. It’s got everything: greed, abandonment, deceit, royalty. If you ask anyone who the monster of this story is, they’d most likely say Rumpelstiltskin, the little man who bargains with the desperate young woman for her firstborn child. But here’s the real story: The young woman’s father wants to impress the king, so he brags that his daughter can spin straw into gold. The king imprisons her over the course of a series of nights and demands that she perform this trick (which she does, thanks to Rumpelstiltskin). The last time, the king tells her that if she doesn’t succeed he’ll kill her, and if she does succeed, he’ll marry her. So of course she does succeed, and then she gets to marry the king who threatened to kill her. Happy ending?

That last story gets me every time. Who’s the real monster? Is it actually the little guy who fulfills his promise? Or is it the father who sells out his daughter to impress the king? Or is it the greedy king who is already rich but threatens the life of a powerless young woman in order to get even richer…and then forces her into marriage? I don’t know about you, but there are a couple of pairs of red-hot iron shoes I’d happily give to those guys.

Riveted

Or perhaps we are to pass judgement on the miller’s daughter, who promises her first born under duress and then ‘fails’ to follow through, by handing the baby over to the gold-spinning dwarf? We are certainly invited to pass judgement on The Frog Queen, who promises to marry a frog if he retrieves her golden ball, and then promptly changes her mind once the frog has given it back. The idea that women have free will is a much newer concept than this tale. The morality of the miller’s daughter is interesting because she is both trapped in a prison, but also an honoured guest. Scholars of feminism will realise that this gilded cage has resonance for many women even today. Any girl who takes the ‘lazy’ way out by getting someone else to magically do her (spinning) work for her is judged harshly. The ethic of work hard and you will be rewarded is very old.

Rumpelstiltskin is a rags-to-riches tale of sorts — we don’t hear about the miller after he gives his daughter to the King, but we can assume he lived in comfort, at least for a good while.

HISTORY

“Rumpelstiltskin” is a German fairytale, also known as “Whuppity Stoorie” in Scotland, “Gilitrutt” in Iceland, “Joaidane” (جعيدان) in Arabic, (Martinko Klingáč) in Slovakia and “Ruidoquedito” in South America. Other versions are found in Israel, Serbia and Japan. Although individual plot details inevitably differ, the core of the story is the same as the German “Rumpelstiltskin”.

A Japanese tale called Oniroku and the Carpenter (だいくとおにろく)has strong Rumpelstiltskin vibes. Instead of spinning straw into gold, a supernatural creature (an ogre) builds a carpenter’s bridge for him. Instead of threatening to take the carpenter’s firstborn, he threatens to take his eyes, unless the carpenter can guess the ogre’s first name.

Rumpelstiltskin stories are likely over 2500 years old, and possibly as old as the Indo-European’s life on the Steppes 6000 years ago. The earliest literary mention of Rumpelstiltskin occurs in Johann Fischart’s Geschichtklitterung, or Gargantua of 1577 referring to an “amusement” for children named “Rumpele stilt or the Poppart”.

There are various ways to spell Rumpelstiltskin and in Germany, in case you were wondering, it’s Rumpelstilzchen. It means ‘little rattle stilt’. (The ending -chen is a German diminutive classifying something as “little” or “dear”.)

A rumpelstilt or rumpelstilz was the name of a type of goblin (also called a pophart or poppart) that makes noises by rattling posts and rapping on planks. The meaning is similar to rumpelgeist (“rattle ghost”) or poltergeist. But at some point, and by the time it was translated into English, ‘goblin’ became ‘dwarf’.

Some of his other names include Tom Tit Tot, Päronskaft, or Repelsteeltje.

There is a version of this tale in sorts of cultures from Japan to Iceland.

As for the Grimms’ collected tale, this one is similar to The Three Spinners. Unlike Rumpelstiltskin, the characters in The Three Spinners are women — from the Queen (rather than the King), the mother (rather than the father) and the three deformed women who show up to do the spinning for the girl.

Most of the early stories related to Rumpelstiltskin involve a fairy trying to take the woman to be his wife. When the Brothers Grimm got hold of it, that’s when Rumpelstiltskin suddenly wants a baby.

Rumpelstiltskin hasn’t been made into a Disney film, though the character Rumpelstiltskin does exist on the TV series Once Upon A Time, played by Robert Carlyle.

Gold has long been associated with fairies and similar creatures (such as hobgoblins). Why? Fairies come from underground, and that’s where treasure comes from, too.

By the by, there is a live action film of Rumpelstiltskin: the 1940 live action one produced in Nazi Germany, directed by Alf Zengerling. I’ve not sought that out.

I consider this fairytale well-suited to the oral tradition. The part where the Queen/miller’s daughter guesses Rumpelstiltskin’s name can be turned into a type of word game where young listeners play with language and come up with all sorts of different, original names each time.

STORY STRUCTURE OF RUMPELSTILTSKIN

Who is the main character of this story? If in doubt, the main character is the one who changes the most. Failing that, the one who learns a life lesson. The King and the Father are monsters of men with zero shades of grey. (When it comes to fairytale archetypes, Kings and Fathers are basically the same person.) This whittles it down to either the nameless miller’s daughter or Rumpelstiltskin.

I will treat Rumpelstiltskin as the main character, not because he is given a name (indeed, in the title) but because the miller’s daughter is entirely passive. In the era this tale existed, she would not have been considered someone even capable of making plans. She is simply a chattel. Even the baby is more important than she is. I presume the baby is a boy, though it is not specified in my version of the fairytale (1979, Cathay Books).

SHORTCOMING

Rumpelstiltskin is a dwarf, presumably shunned by society for this ‘deformity’. He has no status or power despite having the wonderful and rare skill of being able to turn straw into gold.

DESIRE

He wants power. Surely he could get rich on his own, if he can spin straw into gold. His real aim must therefore be to enter the realm of royalty. But as explained by Ravens Shire, Rumpelstiltskin must have a goal, but it is not clear to the audience:

Rumpelstiltskin, despite outward appearances, is neither clear in his goal nor his motivation. On the cusp of it, it would seem that he wants the girl’s first-born baby. However, most fairies in stories don’t ask for the child they want, instead they simply take it. Rumpelstiltskin, however, despite being clearly able to sneak into a prison, being able to weave magic doesn’t just take the child as he obviously could. He tries to get the girl to accept giving the baby to him. What’s more, even after he comes to collect the child, he decides to give her another chance to escape her agreement with him.

Ravens Shire

Ravens Shire has some interesting theories about why Rumpelstiltskin wants this baby:

- he may be a forgotten god

- a baby would offer him love

- he could bring the baby up as ‘the good king’ to eventually replace this evil one

- he is seeking revenge (for what, I wonder?)

- he will utilise the baby’s help at a later date

I’m thinking the original creators of this tale lived in a world where an imp’s/goblin’s intentions were assumed because of pre-existing stories about these creatures. Let’s not forget that the baby twist came quite late, in the mid 1800s. I wonder if this was a throwback to an earlier tale or if it was a brand new twist at that time. (In the same way, Disney have changed certain fairytales in the public imagination. We’ll always think of the dwarves in Snow White as miners, for instance.)

But in Troublesome Things, Diane Purkiss encourages us not to ask why a fairy (or a hobgoblin) would want a baby:

Why did fairies want babies? No one knows. The short, modern answer is that fairies reflect a mother’s love … Babies, especially boy babies, are wanted because everyone wants a baby — or is supposed to. But why do the fairies want human babies? This is not the right question: the point is that babies are, in certain crucial ways, like fairies. we… fairy beings in the ancient world are liminal, borderers; so medieval fairies remain. They wander between the dead and the living.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

Rumpelstiltskin would’ve had this in common with a baby: They were both on the edge of life.

Later in the same book, Purkiss says something else which makes me think again of Rumpelstiltskin: ‘Giving up your baby in exchange for your own power or security is the ultimate crime in agnatic kinship’. That the girl did not want to give up her baby means she is a good girl, because she is conforming to the patriarchal structure designed to keep her in her place.

OPPONENT

Aside from society at large, Rumpelstiltskin’s opponent in this story ends up being the miller’s daughter who, once Queen, has ‘forgotten’ all about her promise: to hand over her firstborn. (I guess PTSD wasn’t a thing back then.)

PLAN

The only way to get power is to act through people connected to the King. Rumpelstiltskin himself must pull strings behind the scene (at night, in the barn), like a puppeteer. If he were to get his hands on a baby of normal height — the King’s son no less — he would be the owner of the ultimate bargaining power.

More specifically, he notices when the King keeps a girl captive and must have somehow overheard the miller boasting. The dwarf’s diminutive size must therefore allow him to be almost omnipresent, blending in to the landscape — his status so low that he is invisible.

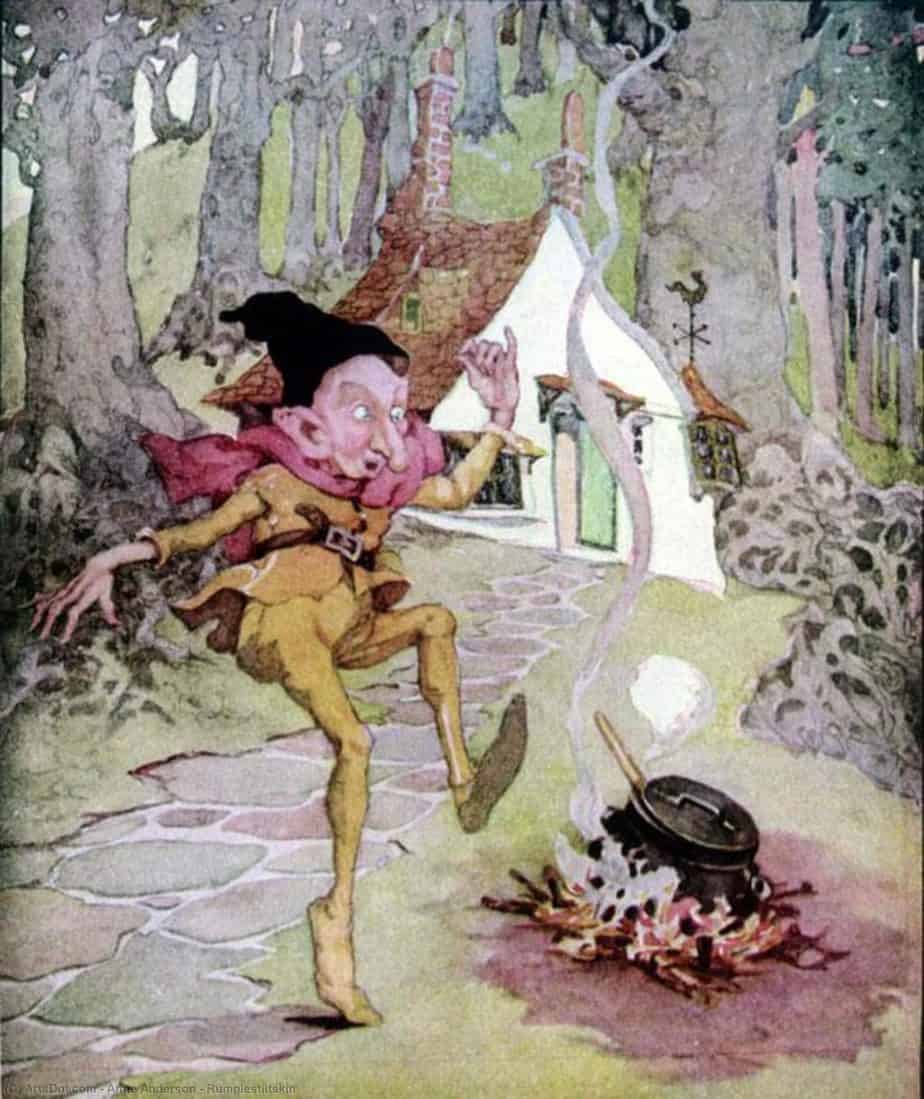

In the illustration below, I feel those birds may represent Rumpelstiltskin’s messengers.

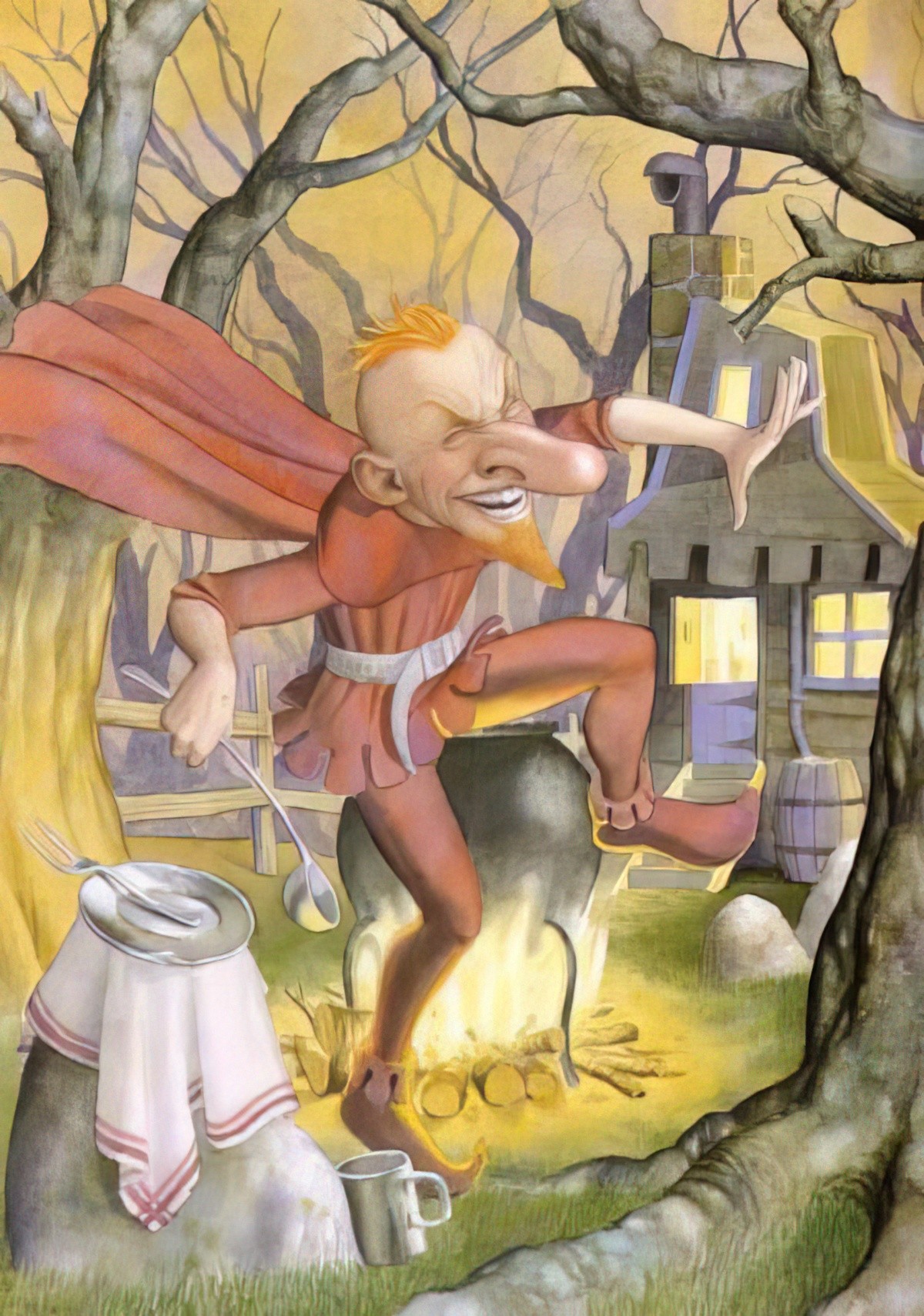

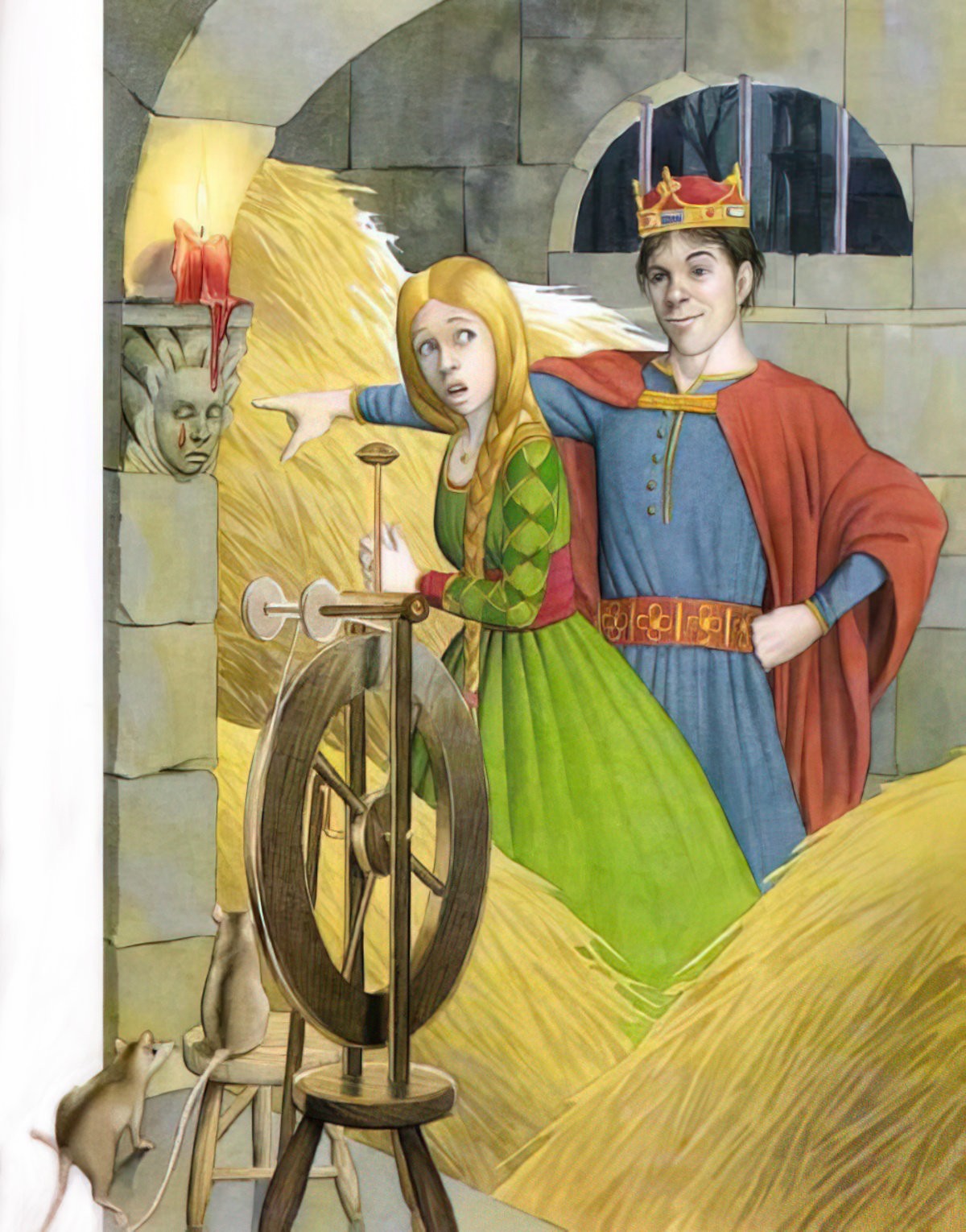

Almost all illustrated versions of Rumpelstiltskin show both dwarf and girl in the barn. Often she is crying; sometimes they are engaged in conversation; other times we see him at the spinning wheel, working away.

BIG STRUGGLE

The big struggle scenes are the episodes in which the miller’s daughter tries to guess Rumpelstiltskin’s name, and the final big struggle scene is of course when she gets it right, after having heard word from a man who passed a man in the woods singing all about his name. The Rule Of Three is used here and in the very sentence structure of some retellings, with repetition of words three times, for instance.

In some versions it is the Queen who sends out her messenger to find the dwarf in the woods, giving the female character more agency by turning her into a trickster who is a worthy opponent for the baddie. In my version she asks for help from the people in suggesting names, but in the end the revelation is an accident.

In the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm tales, Rumpelstiltskin then “ran away angrily, and never came back”. The ending was revised in a final 1857 edition to a more gruesome ending wherein Rumpelstiltskin “in his rage drove his right foot so far into the ground that it sank in up to his waist; then in a passion he seized the left foot with both hands and tore himself in two.” Other versions describe Rumpelstiltskin driving his right foot so far into the ground that he creates a chasm and falls into it, never to be seen again. In the oral version collected by the brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle. (Why cooking ladle? Well, why broomsticks?)

It’s not surprising that we don’t see Rumpelstiltskin tearing himself in two in illustrations for children. Instead we see the seconds leading up to it — there are many images of a dwarf/goblin dancing around a fire. The fire conjures up associations with hell.

ANAGNORISIS

As in Roald Dahl’s The Enormous Crocodile and various other non-bowdlerised fairytales, there is no anagnorisis because the dwarf tears himself in two and dies.

NEW SITUATION

We must extrapolate that the Queen gets to keep her first born. Don’t think about it too hard, however, or you’ll realise she’s living in a permanently abusive relationship under a powerful man who keeps her not only as a gold-spinning slave but as a sex-slave. And now she has no way of continuing to expand his fortune. I don’t envy her prospects.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

"John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt His name is my name too When ever we go out The people always shout There goes John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt!"

In a Sicilian variant, Rumpelstiltskin is none other than the devil himself:

One day, as she sat and wept, a fine gentleman suddenly stood before her. It was none other than Master Paul. “Why are you weeping?” he asked.

She told him everything, and the devil answered, “Good, I’ll spin all this straw […] But when I bring back the yarn on the last day; if you cannot tell me what my name is, you will belong to me and must follow me.

from Beautiful Angiola, L. Gonzenbach ed

Header illustration: Rumpelstiltskin by Anne Anderson