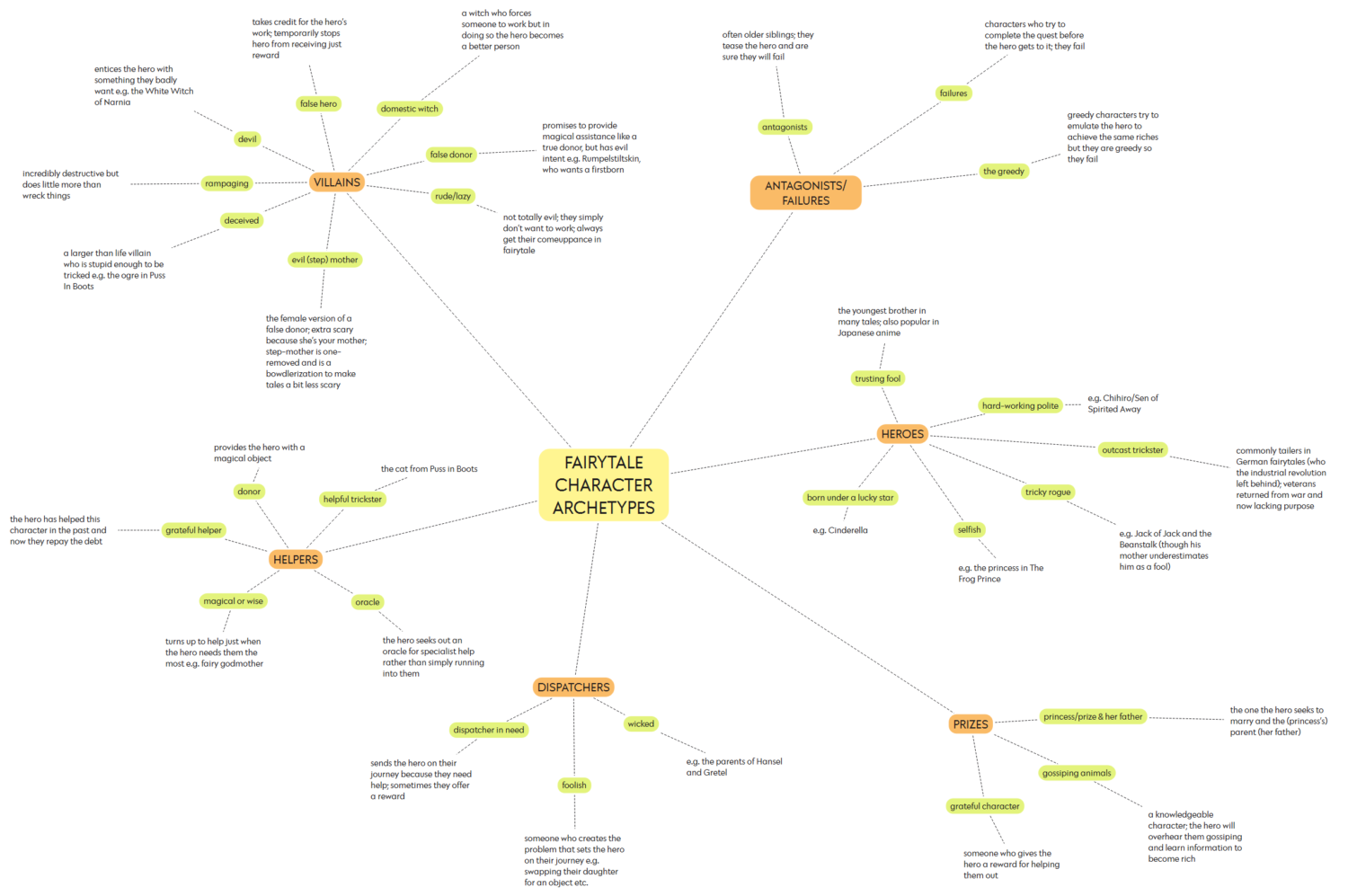

Marina Warner has a great way of thinking about fairytale archetypes: Imagine them as pieces on a chessboard. We know all we need to know about them just from their appearance. Moreover, their position on the board limits the number of possible moves they’re able to make.

If you’ve ever seen Tarot cards, the archetypes on those may also put you in mind of characters from fairytales.

Meet the Forgotten Female Artist Behind the World’s Most Popular Tarot Deck (1909)

Invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory; nothing can come from nothing.

Sir Joshua Reynolds

Even modern stories make use of the stock characterisation of fairy tales, or what I’m calling ‘fairytale archetypes’. There is no need to shy away from using these in your own stories. Audiences love them. The trick is to expand upon them, or, according to your purposes, to subvert expectations and challenge the reader’s prejudices.

Archetypes arrive in statu nascendi (without backstory). This is a huge storytelling advantage, saving time. The reason they have no (on-the-page) backstory: their lives until this point have been predictable.

In fairy tales, famously, character is destiny. Who the personages are, and what happens to them, are completely inseparable. You can predict what will happen to a good princess, just from the fact that she is a good princess. Her identity in the story maps out her future. Conversely, her goodness has no other aspects except those that are revealed by her marrying a handsome prince. That’s all her goodness really means; though we will of course have seen it in action in acts of kindness or victimhood at the beginning of the story, so we know that it is there. In true fairy tales, as opposed to literary hybrids smuggling in the techniques of the novel, there are no individual characters, only types.

Good princess; bad princess.

Witches.

Fairy godmothers.

Genies.

Kings who set tasks for suitors.

Ogres and giants.

MentorsThese beings do not exist in the environment of the child who, at the same time as hearing about Snow White, is also thrilled by stories of door-opening. But the vocabulary of types is actually easier to acquire, in some ways, than knowledge about the child’s own world, because the fairy-tale world is so perfectly self-explanatory. Every appearance by a witch is a complete, sufficient demonstration of what a witch is. In life, knowledge of other people’s natures is both important and relatively hard to come by; it depends on a long loop of inferences moving gradually from the things people do and say, to conclusions about what they’re like. Children can afford to be much less cautious about the information in stories — much quicker to decide. Arthur Applebee asked a group of pre-school children to tell him the characters of a list of animals. They were more certain of the stereotypical personalities of animals they could only have met in stories, such as brave lions or sly foxes, than of the characters of dogs or cats, where experience of specific dogs and cats came in to complicate the picture. Story characteristics are prepared for reception, so to speak; they’re consistent, they don’t contradict themselves, and they’re dispensed at the pace that understanding demands.

The Child That Books Built, Frances Spufford

CHARACTERS ARE ‘NOT ACTUALLY CONSCIOUS’

“Conventional stock figures”: there is no psychology in a fairy tale. The characters have little interior life; their motives are clear and obvious. If people are good, they are good, and if bad, they’re bad. Even when the princess in “The Three Snake Leaves” inexplicably and ungratefully turns against her husband, we know about it from the moment it happens. Nothing of that sort is concealed. The tremors and mysteries of human awareness, the whispers of memory, the promptings of half-understood regret or doubt or desire that are so much part of the subject matter of the modern novel are absent entirely. One might almost say that the characters in a fairy tale are not actually conscious.

They seldom have names of their own. More often than not they’re known by their occupation or their social position, or by a quirk of their dress: the miller, the princess, the captain, Bearskin, Little Red Riding Hood. When they do have a name it’s usually Hans, just as Jack is the hero of every British fairy tale.

The most fitting pictorial representation of fairy-tale characters seems to me to be found not in any of the beautifully illustrated editions of Grimm that have been published over the years, but in the little cardboard cut-out figures that come with a toy theatre. They are flat, not round. Only one side of them is visible to the audience, but that is the only side we need: the other side is blank. They are depicted in poses of intense activity or passion, so that their part in the drama can be easily read from a distance.

Philip Pullman, The Guardian

BOYS AND BROTHERS

Brothers in a fairy tale will often manifest a different aspect of personality. This provides a moralistic tale about which traits will get you far in life and which will lead to your downfall.

For example, the lazy brother, the haughty brother and the smart brother. The youngest is usually the best. This is because the youngest brother was the least privileged — in a culture of primogeniture it was the eldest son who inherited everything. These tales teach younger brothers that they can still do okay on merit — we’re still telling ourselves this today.

GIRLS AND SISTERS

When it comes to fairytale sisters, good and evil are connected to how they look. Pretty girls are good girls. This is an obvious case of physical discrimination but is in line with other fairytale archetypes in which What You See Is What You Get, and if that’s not the case, it’s because you’ve been deliberately deceived.

In the best-known folktales there are several possible roles for the adult male protagonist. He may be a prince, a poor but ambitious boy, a fortunate fool a traveling vagabond, or a clever trickster. But if you are the female protagonist of one of the fairy tales most popular today, there are only two possibilities: either you are a princess or you are an underprivileged but basically worthy girl who is going to become a princess if she is brave and good and lucky.

If you are already a princess when the story starts, you usually have a problem. Very likely you need rescuing from some danger or enchantment. Maybe you have been promised to a dragon or promised yourself to a dragon; or you might have been kidnapped by a witch or enchanter, who asks impossible riddles or sets impossible tasks for your would-be rescuers. Possibly it is your father, the king, who has set these tasks. Or perhaps you are just very difficult to please, like the princess in “King Thrushbeard,” and set the tasks or riddles yourself, to drive away possible suitors.

Alison Lurie: Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The subversive power of children’s literature

Before fairy tales were written down by men, the heroines of fairy tales were very often courageous young women who retained their wits during times of adversity. A look into the history of Little Red Riding Hood is a good example of a heroine who was deliberately stripped of power, in this story’s case, mostly by The Grimms.

KINGS

There’s not much point separating the father from the king — they’re basically the same archetype. They’re either the head of their household or head of their kingdom.

VILLIANS

Villains often have seductive powers, as in the witch who is an ugly old crone underneath, but can shapeshift and trick men into thinking she’s attractive to them.

The rise of the fairytale created a tectonic shift in children’s literature and revealed that something had long been off kilter. Fairytales—sometimes referred to as “wondertales” because they traffic in magic—opened the door to new theatres of action, with casts of characters very different from the scolding schoolmarm, the aggravated bailiff, or the disapproving cleric found in manuals for moral and spiritual improvement. Books were suddenly invaded by fabulous monsters—bloodthirsty giants, red eyed witches, savage blue beards, and sinister child snatchers— and they produced a giddy sense of disorientation that roused the curiosity of the child reader.

Maria Tatar, Enchanted Hunters

Villains are also very often cannibalistic, especially ogres.

THE WISE WOMAN

The wise woman is a good witch.

The wise women of modern fiction come from all classes of society. Some, like Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Ramsy and E.M. Forster’s Mrs Wilcox, are upper-class or upper middle-class. Others, such as William Faulkner’s Dilsey and the cook Berenice Brown in Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding, are servants. Many of them are also in a sense nature goddesses whose power is related to a semi-magical connection with the earth, the seasons, and the processes of growth and creation. They can be recognized by their knowledge of plants, their instinctive sympathy with children and animals, and their intuition, which sometimes operations at the level of ESP.

Alison Lurie: Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The power of subversive children’s literature

The wise woman archetype can also be found in:

- Of The Farm by John Updike

- Wise Child by Monica Furlong

She couldn’t be a prince, and she’d never be a princess, and she didn’t want to be a woodcutter, so she’d be a witch and know things.

Terry Pratchett

THE PAUPER

America is the wealthiest nation on Earth, but its people are mainly poor, and poor Americans are urged to hate themselves . . . Every other nation has folk traditions of men who were poor but extremely wise and virtuous, and therefore more estimable than anyone with power and gold. No such tales are told by the American poor. They mock themselves and glorify their betters.”

Jessica Bruder, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century

THE MILLER

The Folktale Podcast

THE SPINSTER/WEAVER

The skills of weaving, spinning and knitting were vital to clothe and keep warm members of every class, race, religion or social group from the poorest to the richest. And so, we find wool, yarn and thread and the working of those materials rooted very deeply in the folklore of countries around the globe.

In this episode, Folklore Podcast creator and host Mark Norman discusses the folklore associated with wool, thread, spinning and associated crafts, through folk and fairy tales, customs and more.

FOOLS AND JESTERS

Fools and Other Unwise Persons, a categorisation from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966

Consider the jester an inverted king. Notice how one of the jesters in the image above is standing on his head.

The jester is also a sacrificial victim, associated with the abnormal. Because the jester is abnormal, he has supernatural/magical powers.

The archetypal fool figure extends back to Dionysus festivities, where ecstatic animalistic trance-like behaviours were encouraged. During the Middle Ages (from the Roman period into the Dark Ages*), as Christianity took hold, all forms of theatre were suppressed in favour of didactic stories, and the fool wasn’t exactly considered a good role model. But you can’t get rid of the fool so easily, and he never really went away.

(*Actually, don’t call them the Dark Ages. “Dark Ages? What Dark Ages!? Did the light go somewhere? No, no it didn’t… In this episode, Ken and Glen discuss how a very misleading term for the Middle Ages came about (hint – it has something to do with Rome!) and why it has rightly fallen out of use…by them, anyway.”)

The fool stayed on as:

- Mimi

- jongleurs

- histriones

- etc.

These guys sang, danced, mimed, made music and performed acrobatics. Then they made a comeback big time, from about the 10th century CE. It was actually the churches who realised the best way to convert and retain was to make Bible stories fun, so this whole new genre popped up of Bible stories interspersed with comical interludes. These are known as Miracle Plays or Mystery Plays. Believe it or not, the funniest character in one of those church plays was Satan. He was the character who got the best lines and the biggest laughs. Fools aren’t part of the Christian cast of characters, but what’s a comedy without a decent fool? Fools came into it. These fools were ‘wanderers’, which includes minstrels and so on.

We can see depictions of the fool as early as the mid 1400s, on tarot cards. He’s wearing clothes made out of light-coloured rags and has feathers in his hair, probably not to make himself look pretty so much as to make him look like an animal like people did during Dionysus activities. (The word we need here is ‘zoomorphic’.) Devil horns also morph someone into an animal, releasing them from their restrictive human status. We’re talking about pre-Christian rituals here.

I’m also talking about Europe, but every culture has its own fool archetype.

From Tibet to Africa, and places in between, many cultures have set aside a special place for fools. We may be most familiar with this from Shakespeare’s plays where court jesters appear, like the wise one who has a role in King Lear. And to all appearances, court fools had an enviable job since they could say what they liked with impunity and be pranksters without fear of reprisal. Protected by their special status, given room to act up, making acute but silly comments from the side of the stage, not taken very seriously–the fool, in many ways, resembles the child. Hence, the appeal of this figure to children: the fool is their cousin. Hence, too, the childhood business of “playing the fool.”

Jerry Griswold

A story all about the foolishness of a fool is sometimes called a ‘noodlehead tale’. Contemporary sit-com characters take elements from the classic fool or noodlehead tale, in which the audience takes delight at watching a character do one stupid thing after another, never learning from their mistakes.

But there’s a difference between the sort of fool an audience likes to watch and a real life fool. The fictional, comedic fool may be bumbling and stupid but they also have a certain wisdom.

George Kostanza of Seinfeld is a good example of this archetype. Though he never learns from his mistakes (at work, with women etc.) he also has a certain pragmatic wisdom about him. He knows that lying can get you a long way, and it often does. We like watching him get away with things, and we also like watching him fail. Succeed, fail, succeed fail; that’s the fool cycle.

These fools exist to show the audience that the world is a foolish place in general. Everyone is a fool in their own way. Win some, you lose some.

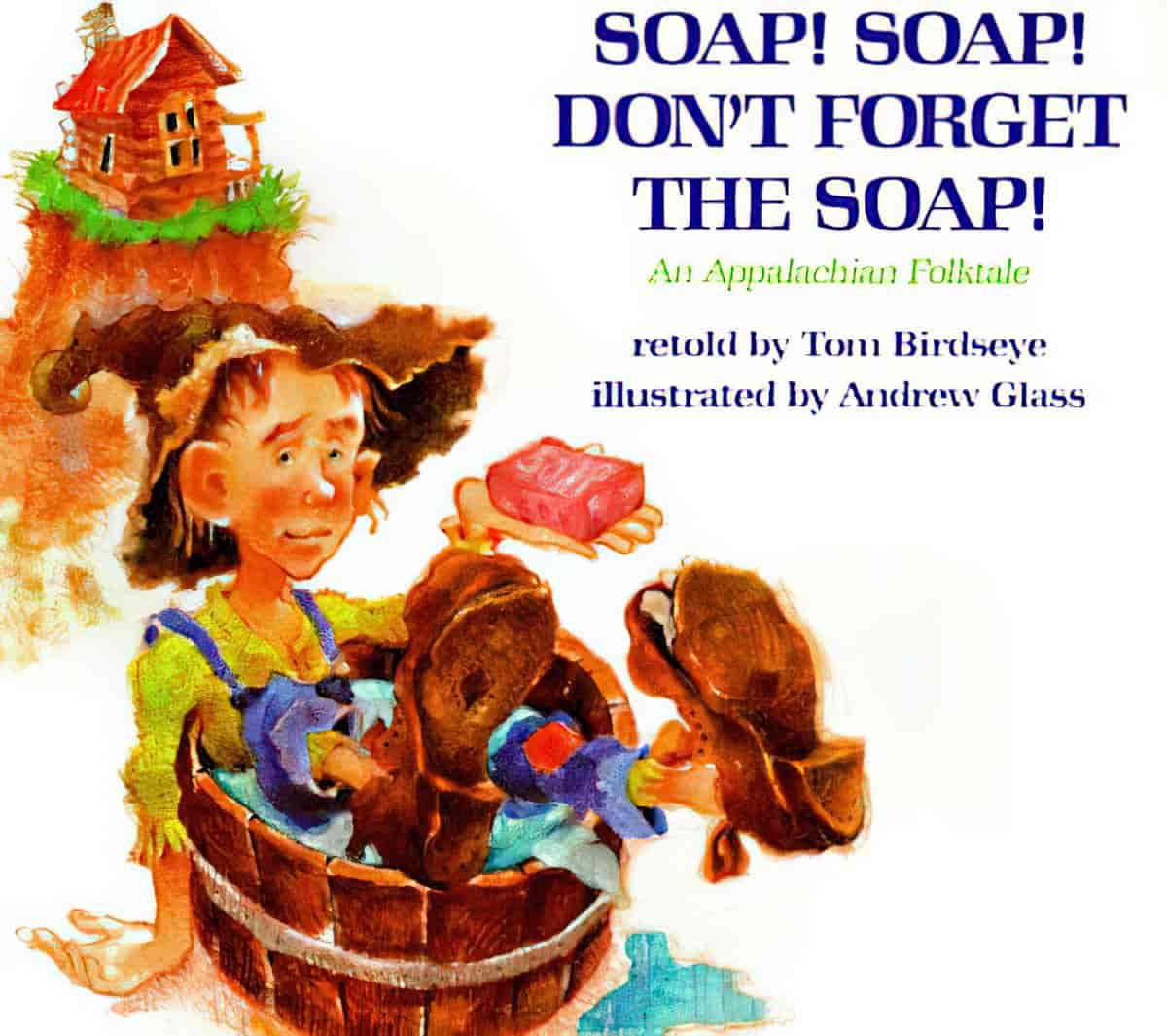

NOODLEHEAD TALES

Sometimes called simpletone tales or fool tales, noodlehead tales are humorous stories about absurd situations in which the stupidity or foolishness of the characters plays a central part. The main character in a noodlehead tale usually makes the same mistake over and over until the resolution of the story. Although foolish and bumbling, the noodlehead is often wiser than the other characters, suggesting that the rest of the world is foolish and unable to recognise wisdom.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

Picture book examples of noodlehead tales:

Soap! Soap! Don’t Forget The Soap! by Tom Birdseye and Andrew Glass. A forgetful boy gets himself into trouble. (1993)

Flossie and the Fox (1986)

Lazy Jack by Russell Ayto (1995)

Piggie Pie! (1995) by Howard Fine

The Fool Archetype In Picture Books

- Soap! Soap! Don’t Forget The Soap! (1993), illustrated by Andrew Glass

- Flossie and the Fox (1986) illustrated by Rachel Isadora

- Lazy Jack (1995) illustrated by Russell Ayto

- Piggie Pie! (1995) illustrated by Howard Fine

There’s a subcategory of the fool which is a very old archetype in folk tale, in which a character understands the world in an overly literal way. In contemporary stories, this character is often read as autistic, whether on or off the page.

MENTORS

When a hero (or saviour/chosen one) character embarks upon a mythic journey they will encounter a number of characters. Some of them will be opponents, some allies. The mentor is a type of ally who will hand the hero a secret, a weapon, a magic spell, something like that.

The mentor doesn’t get much credit.

Each of these [saviour] heroes had a guide to help them along the way. So are the actions of…Harry [Potter], Frodo and the like…the decisions of those around them, forcing their way into people’s lifves? Is it the mentorship tat makes them great? Are these [heroes] just fitting a predetermined mold of what greatness means? If so, what does that say of us, those without that support?

Sean Dicker, PanelxPanel

In Cinderella, it’s the fairy godmother.

The mentor in a large number of stories has been ostracised from society because they don’t conform. Witches in the middle of the forest fall into this group.

In the children’s film Monster House, the kids find their mentor playing video games at the parlour. Likewise, this guy is slightly ostracised from mainstream (accceptable) society and it’s his madness that makes him useful. This is mad people are coded as mad because they see the truth, when everyone else still has the wool over their eyes.

The novel Curious Toys by Elizabeth Hand is an interesting example because the story uses the legend of a real person (reclusive, prolific artist Harry Darger) to function as mentor.

Header painting: Frederick Judd Waugh – Chess Players