Is fairy land real? Some children’s stories would like us to think so. Their endings contain a ‘wink’, encouraging readers to carry the possibility of fantasy lands with them, even after the story draws to a close. This is one way of achieving resonance. We might argue this is a cheap trick.

Enter Richard Dawkins, who wrote The Magic of Reality partly as an antidote to magical thinking, which he famously despises. His main argument? Reality is far more interesting than anything fiction writers can make up. In this he is probably right.

Magic takes many forms. Supernatural magic is what our ancestors used in order to explain the world before they developed the scientific method. The ancient Egyptians explained the night by suggesting the goddess Nut swallowed the sun. The Vikings believed a rainbow was the gods’ bridge to earth. The Japanese used to explain earthquakes by conjuring a gigantic catfish that carried the world on its back—earthquakes occurred each time it flipped its tail. These are magical, extraordinary tales. But there is another kind of magic, and it lies in the exhilaration of discovering the real answers to these questions. It is the magic of reality—science.

marketing copy of The Magic of Reality

Is it possible to enjoy fantasies and understand science at the same time? Cognitive science has already told us that humans are plenty capable of holding two completely contradictory beliefs at the same time. As for fantasy versus science, I can’t answer for other people, but I had a different relationship with fantasy as a young kid.

When our year two teacher read us The Witches by Roald Dahl and described what a witch looks like, I examined her very closely. I was never sure whether she had square toes under her shoes, but she didn’t wear gloves and her spittle was not blue. My coding of the fantasy world presented by Dahl blended with my reality in a way no fantasy can do for me today. I now approach fantasy stories as commentary on real world societies and politics, acknowledging that fantasy can be an excellent vehicle for big ideas, presented symbolically.

For young children, fantasy stories work differently. At the same age I left an earnest note for the tooth fairy and was only just starting to doubt the logic around Father Christmas. After reading Enid Blyton, which I understood as fiction, I thought the rocking chair at home really might grow wings and spirit me away. I have excellent memories of sitting in that chair and wishing. Did I ever really believe any of this, deep down? I’m not sure, but I certainly don’t now. Developmental milestones took care of that.

But what if I’d grown up in a different subculture, anti-science, anti-expert? Might a childhood diet of fairies and witches then have a damaging effect upon my ability to distinguish fact from fantasy? The popularity of fantasy on children’s bestseller lists today shows that the majority of adult gatekeepers aren’t worried about children in this regard, instead going with the idea that kids are smart enough to work out the difference for themselves. ‘Let kids be kids’, now more than ever, perhaps.

I’ve long wondered about stories which encourage kids to blend fantasy and reality. But I may have been worrying about the wrong thing.

‘Proof’ of Fairy Land

In The Polar Express by Chris Van Allsburg, the child comes back from a fantasy land with just one treasure as proof of the reality of magic. (Technically he’s lost it via the hole in his dressing-gown pocket, but it comes back to him via Santa, with a finders keepers understanding.)

The child does not tell his parents the whole story when asked where it came from — he doesn’t lie (that would make him unlikeable), but nor does he practise transparency. We assume because the adults would not believe him even if he told his truth. This conforms to another ancient fairy belief: Gifts from fairies are dangerous; blab about it and the gift will dissipate. Hell may rain down upon you.

By the way, something else is going on in the ending to The Polar Express: Only those who ‘truly believe’ can hear the bell. Telling the story from the extradiegetic position of an older man looking back, the sister loses her ability to hear it as she grows older, but the narrator main character does not. This ending functions as a metaphor for how children learn to prioritise an empirical understanding of the world over fantasy. This adult view on a world without magic is framed as a tragic loss for Sarah.

Somewhat cagily, I point out that auditory hallucinations are more common than you might think, even among adults. (As are false memories.)

In short, the brain is not trustworthy. If the main character of The Polar Express hears the tinkle of a broken bell, it might not be magic after all.

Other picture books use the same wink to end a story, but according to the logic of the narrative, a so-called magical item isn’t always coded as magic. An example of that can be seen in There’s A Crocodile Under My Bed! Whereas the child in this story has spent the story believing there’s been a real crocodile under her bed, the story ends with her father pulling out a crocodile crafted of egg-carton. The takeaway message here is directly inverse to that in The Polar Express: The child can enjoy magical ideas, but fantasy is never real.

Souvenirs from ‘Fairy Land’

The one souvenir brought back from fairy land is a trope straight out of Romance. Mythology around a famous glass beaker is an excellent example of this trope, and like The Polar Express, blends fact with fiction.

I’m talking about the beaker in the Victoria & Albert museum known as the Luck of Edenhall. There’s a photo of it on Wikipedia. It’s special even without the supernatural folklore; glass artifacts rarely survive intact across centuries, yet this is a pristine example of glassware which has survived since the 14th century.

Adding to the magic story around it: A butler of Eden Hall received it after meeting fairies while out on a picnic. Eden Hall no longer exists. Amazingly — magically — this glass vase has survived longer than the building which once housed it. This is actually proof against fairy magic because apparently the fairies yelled after the butler that if the vase ever broke this would signal the downfall of Eden Hall. Yet here we are. Hall, gone. Glassware, intact.

Fairies and the Fall of Constantinople

Much has been said about this watershed historical event elsewhere, but how does the fall of Constantinople relate to magical objects brought back as proof of fairy land?

The capturing of Byzantine was important to military history but it is also important to the history of shopping. Europeans were taking luxurious new consumer goods back from the East to Europe. The vase which ended up at Eden Hall is the stand out example of one such luxury item brought back to England during that era.

Exotic Eastern luxury items were so very luxurious that Europeans couldn’t believe they’d been made by human hands. These items merged with fairy lore, and ideas around fairies, luxury and exoticism.

Weren’t people silly back then? They really thought these things had been made by fairies.

Ha. I’m reminded of contemporary stories of aliens and the Egyptian pyramids, which according to some white conspiracy theorists must have been built by aliens because the notion that a non-white Imperialist culture could manage a feat more technologically advanced than their own is so beyond them that an alien story is easier to believe. There is even a documentary series about how aliens built the pyramids on A+E’s ‘History’ Channel. A very similar prejudice surely led to those medieval fairy stories. Objects stolen from Istanbul were so exquisitely beautiful to white Europeans that it was easier to believe they came from fairies. Also, that way they didn’t have to feel guilty for stealing them.

Story Structure of a Fairy Cup Legend

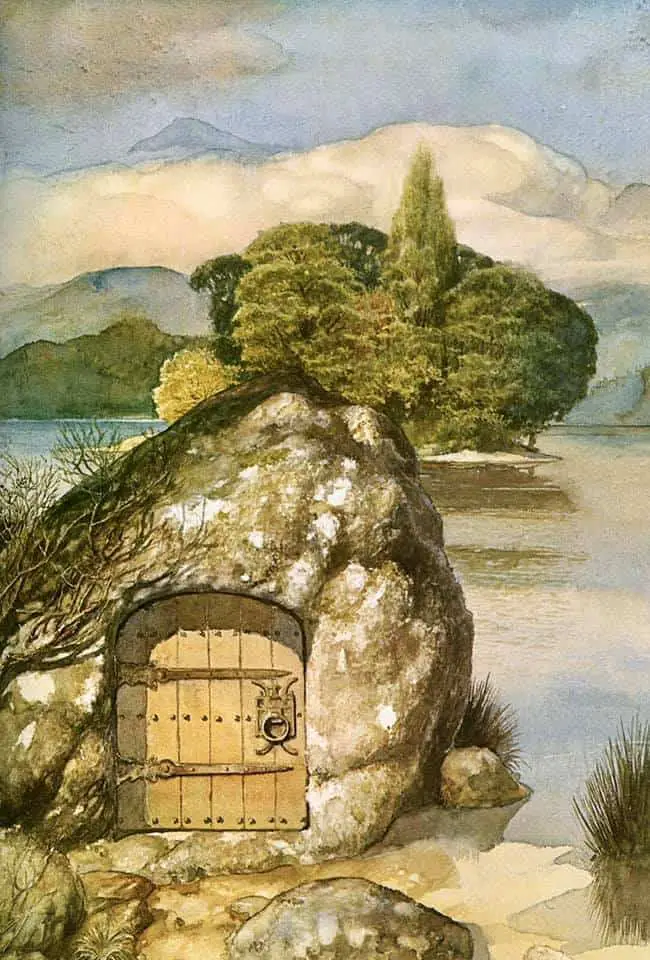

White European cultures therefore have many stories in which precious items are ‘found in the ground’. The fairy cup legend typically goes like this:

- The main character is walking around in nature when a mysterious hole opens up in the ground.

- Small creatures are revealed to be living under there.

- A fairy-sized creature offers the main character a drink from a cup. The cup is often horn-shaped. It is usually made of gold or something similarly expensive.

- The main character refuses to drink, knowing that to consume the food of the fairies is to be drawn into their dangerous world. But if they don’t take the offering, bad luck will befall them anyway. To get around this, they might pretend to take the drink, but then secretly discard it — coffee in the pot plant.

- The main character doesn’t take the drink but can’t resist stealing the cup, though. Hey, it’s an expensive cup.

- The main character then feels guilty and also scared.

- There’s a chase sequence. Fairies want their cup back.

- The fairies don’t get their cup back, and nor did the real people of Byzantine. Instead, the precious object ends up owned by white European nobility or perhaps by the church.

Here is a list of Fairy Cup Legends. They are related to King Arthur Holy Grail mythology. The fairytales have been classified as ‘migratory type’ tales and were popular in the following countries:

- England

- Scotland

- The Isle of Man

- Germany

- Norway

- Sweden

- Denmark

It’s one thing to worry about whether children will eventually learn the difference between fantasy and reality, encouraged to believe in magic by stories such as The Polar Express. Fairy land is indeed real. Fairy land stands for cultures Othered and exoticised by our own, past and present.

So perhaps we should be asking young readers a different question after reading a modern Fairy Cup Legend such as The Polar Express:

Who does that bell belong to, and why did the boy bring it home? As precious as it is to this sympathetic main character, ‘magical’ souvenirs have invisible victims. That bell may have flown loose from a galloping reindeer’s reins, but that does not mean it automatically belongs to the white boy.