Alison Lurie has pointed out that every national folk tradition seems to produce two types of supernatural being:

- The national type is idealised

- The national type is mocked or caricatured

Ireland

- heroic fairies (daoine sidhe (“theena shee”). Human size or larger, beautiful, passionate, noble, skilled in warfare, poetry and music.

- cluricaune and the leprechaun. Squat little Paddy types who enjoy whiskey, tobacco, singing coatse songs and hiding their gold.

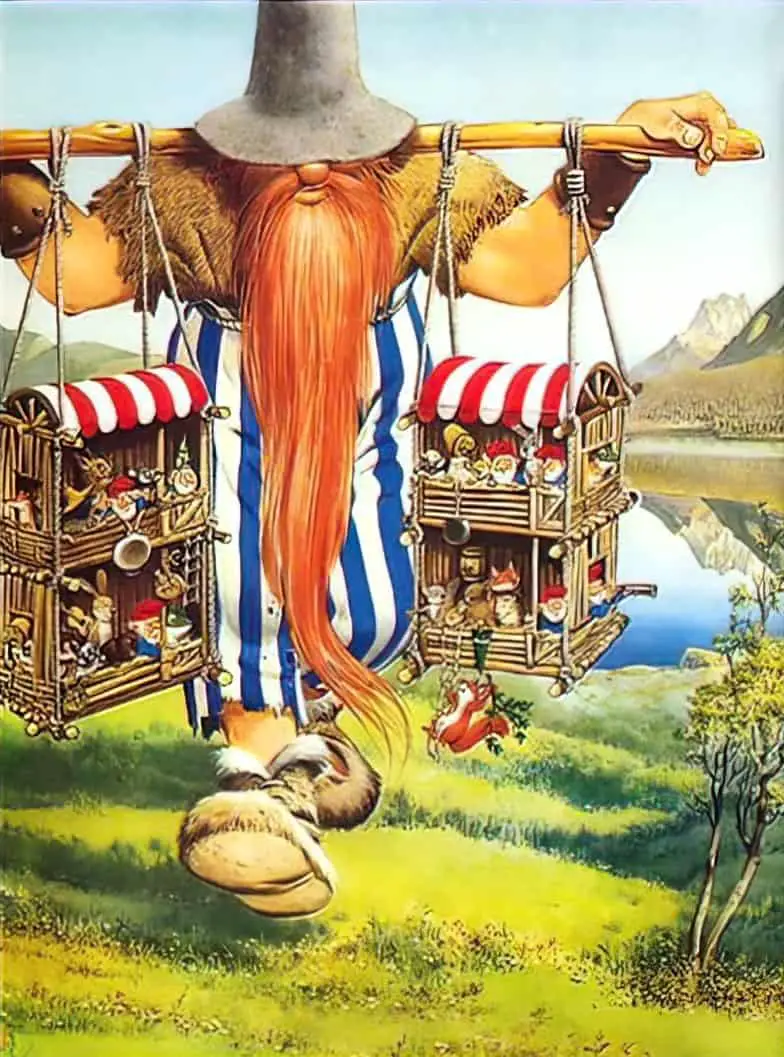

Scandinavia

- tomte specialize in agriculture

- nisse specialise in horseplay

Italy

- folletti pursue women

- The Mazzamurello is a whimsical fantasy creature of the Italian fairy-folk tradition, who scares bad people but is generous with good ones.

Arguably, these mocking types of fairies emerged because it’s generally taboo to make light of your national characteristics, so attributing these characteristics to fantastic creatures is one way of talking about it.

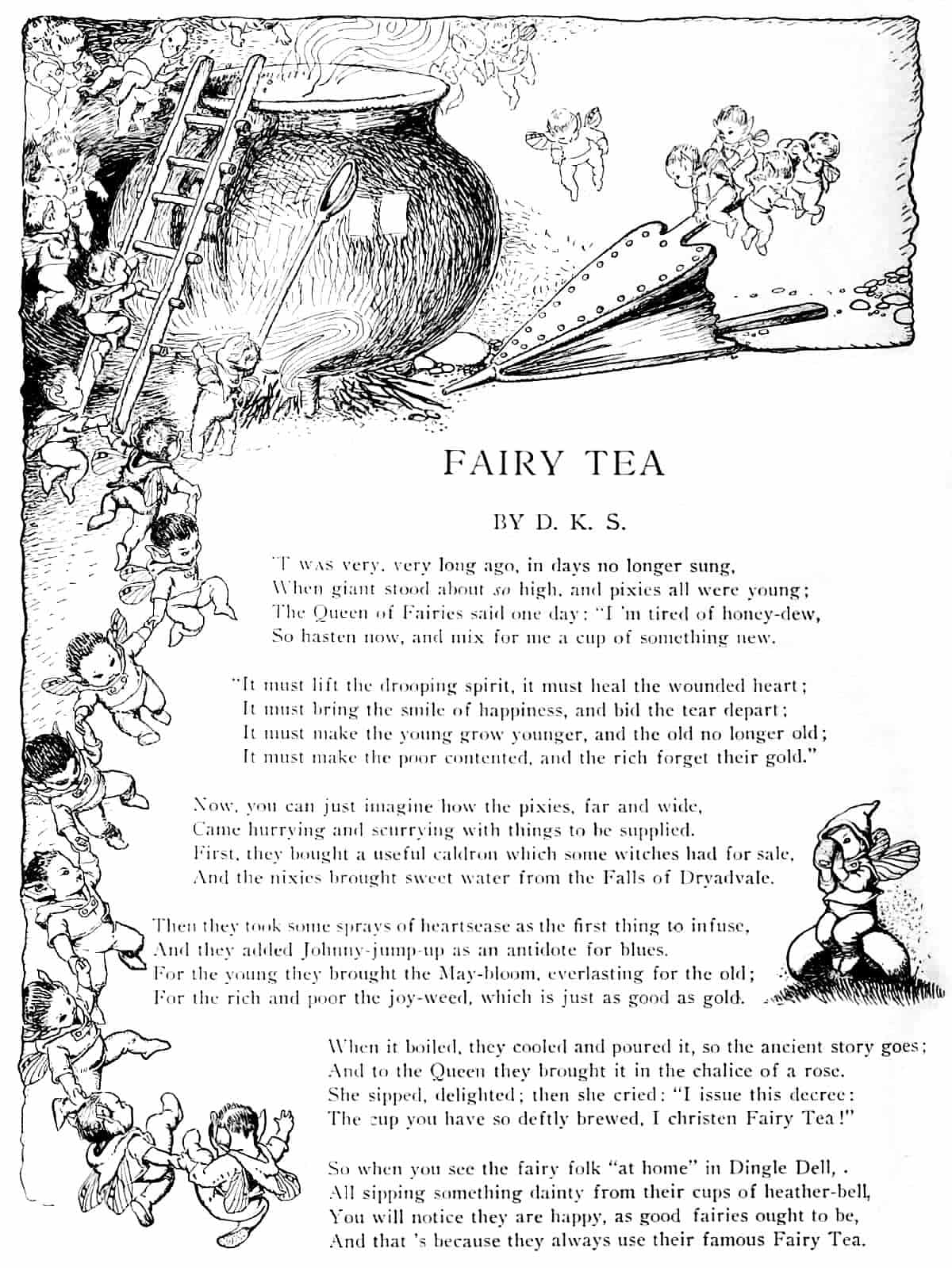

GOOD FAIRIES, BAD FAIRIES

FAIRIES AND THE REFORMATION

Over time [reformation] tends to delete the grey areas of folklore. Everything is black or white. You’re either going to the hot place or you’re going to heaven—there’s no in-between. There’s no purgatory; there’s no limbo. Similarly, every supernatural entity has to come from either heaven or hell. All those middling beings like fairies and ghosts also get dropped. Anything that does bad stuff is, therefore, a demon.

Diane Purkiss

The Influence Of Tinker Bell (1904)

J.M. Barrie wrote his stage play Peter Pan with the conventional hodgepodge collection of fantasy figures and settings seen in all sorts of stories from Mother Goose to Dick Whittington:

- a mermaids’ lagoon

- forest full of wolves

- Indians

- the pirate ship

Then of course these are the conventional pantomime characters. But one thing Barrie did differently was the fairy. Tinker Bell appears only as a moving light and a silvery ringing in the original play. Moreover, she is both the Good Fairy and the Bad Fairy all rolled into one. At times she is loving and protective toward Peter but she is also murderously jealous of Wendy.

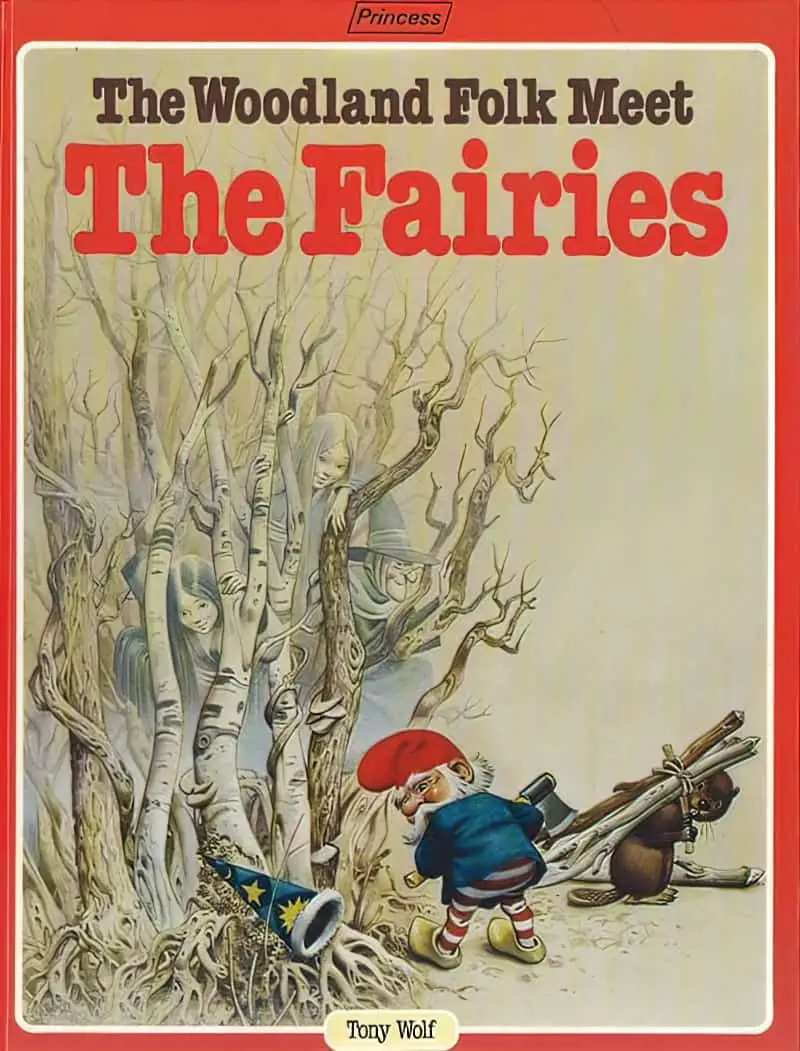

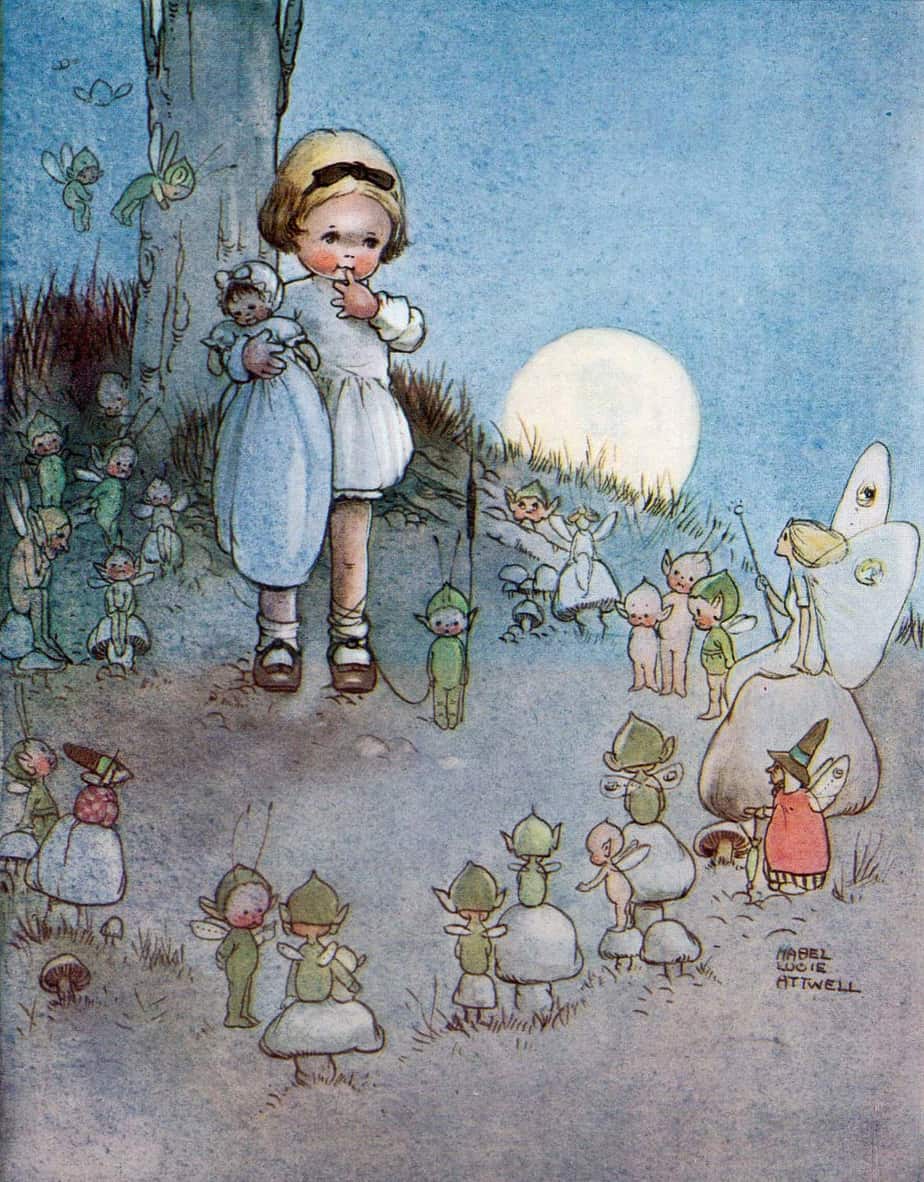

The Cult Of Fairies In 1970s America

In the 1970s and early 1980s, when many strange social phenomena occurred, there was a proliferation of fads and cults, some of Eastern or quasi-Eastern origin, others homegrown. One of the most widespread, though least recognized, was the fascination with fairies, elves, gnomes, unicorns, dragons, and the like, which continues to some extent today. Though it never became an organized faith, at its height it attracted more followers than est, Dianetics, Krishna Consciousness, or Sun Myung Moon and sold millions of books, posters, calendars, and T-shirts. Like other cultus of the time it appealed mainly to young people, often the most privileged and best educated among them; in a survey of 350 under-graduates at Brown University, for instance, nearly 100 declared that they believed in hobbits, while only 40 claimed to believe in angels.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The power of subversive children’s literature. (Full essay here)

Lurie called this cult ‘pixiolatry’.

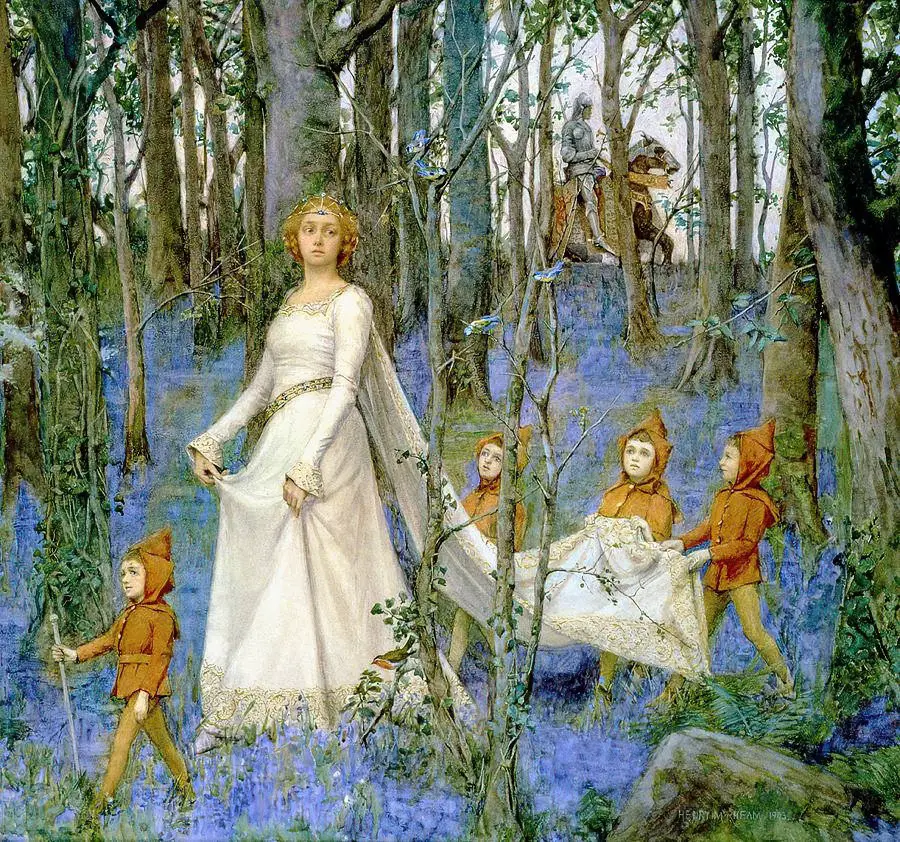

Fairies In British History

Fairy-type characters have been invented all over the world but my own version of fairy comes mostly from the English books I read growing up.

There was not a village in England that had not a ghost in it, the churchyards were all haunted, every large common had a circle of fairies belong to it, and there was scarce a shepherd to be met with who had not seen a spirit.

a writer in the Spectator in the early 1700s, writing of the 1600s

Fairies were common tormentors in England, Ireland, Scotland and that general area.

In England their king was Robin Good-fellow. He was a classic trickster who lead travellers astray at night, taking them into bogs and forests. In the late 1500s Robin Good-fellow was the inspiration for Shakespeare’s character Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Closely allied to fairies:

- Will-o’-the-wisps — imps which glow at night above marshland. Travellers mistake these for lights on at night. These remind me of Japanese Kodama, which you may have seen in Princess Mononoke. (They also remind me of moths.)

Fairy or Faerie?

Tolkien wrote what he himself called fairy-story. By this he meant stories of “Faerie, the Perilous Realm,” which “contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted.” The Lord of the Rings […] was intended by its author for adults; but Tolkien thought there should be fairy-story (in his sense of the phrase) within the measure of children. The Hobbit is recognizable (sometimes all too recognizable) over wide areas of children’s and indeed of general literature.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

C.S. Lewis was heavily influenced by Tolkien. But he insisted that he only wrote children’s stories because it was the best form for expressing what he had to say.

The Function Of Fairies In Children’s Stories

Fairies Soften Harsh Plots

In The Water Babies there is murder, tragedy, shipwreck and sudden death, but the effect is softened by the justice of the two great Fairies who arrange the fates of all the creatures in this natural and supernatural history — and as Tom is half supernatural himself, justice is seen to be done.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

The White People

Available online at Gutenberg Press

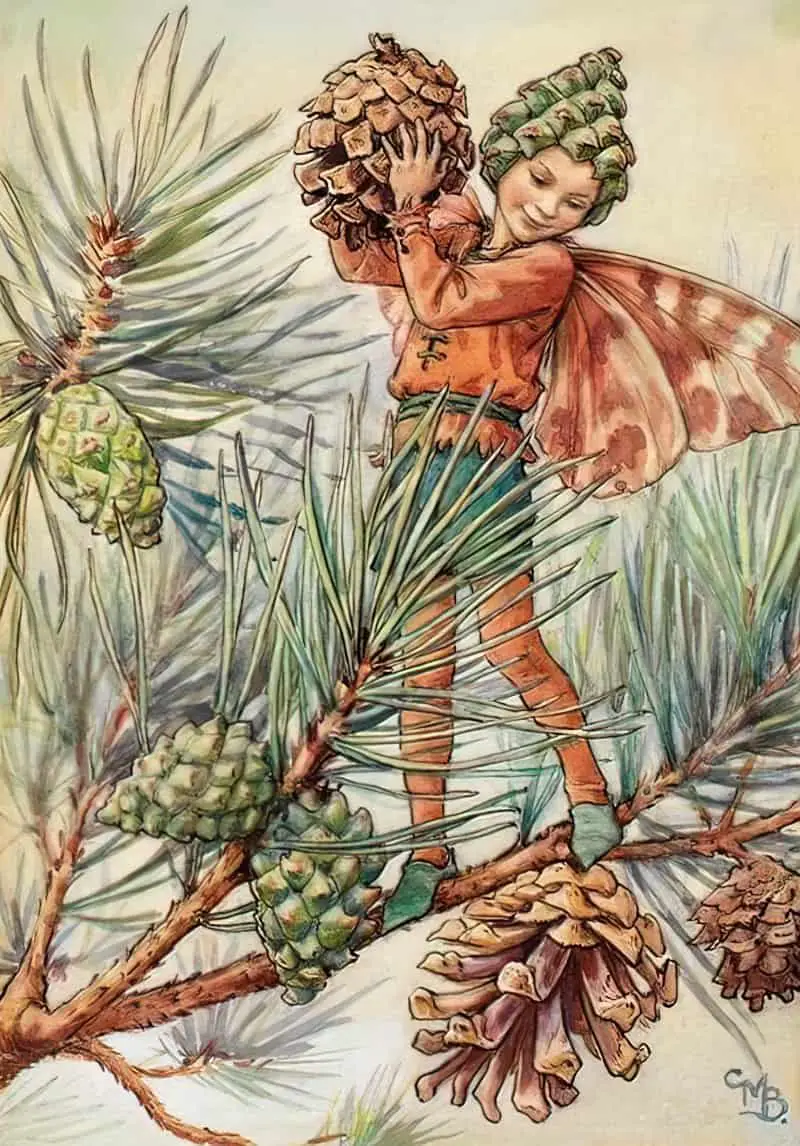

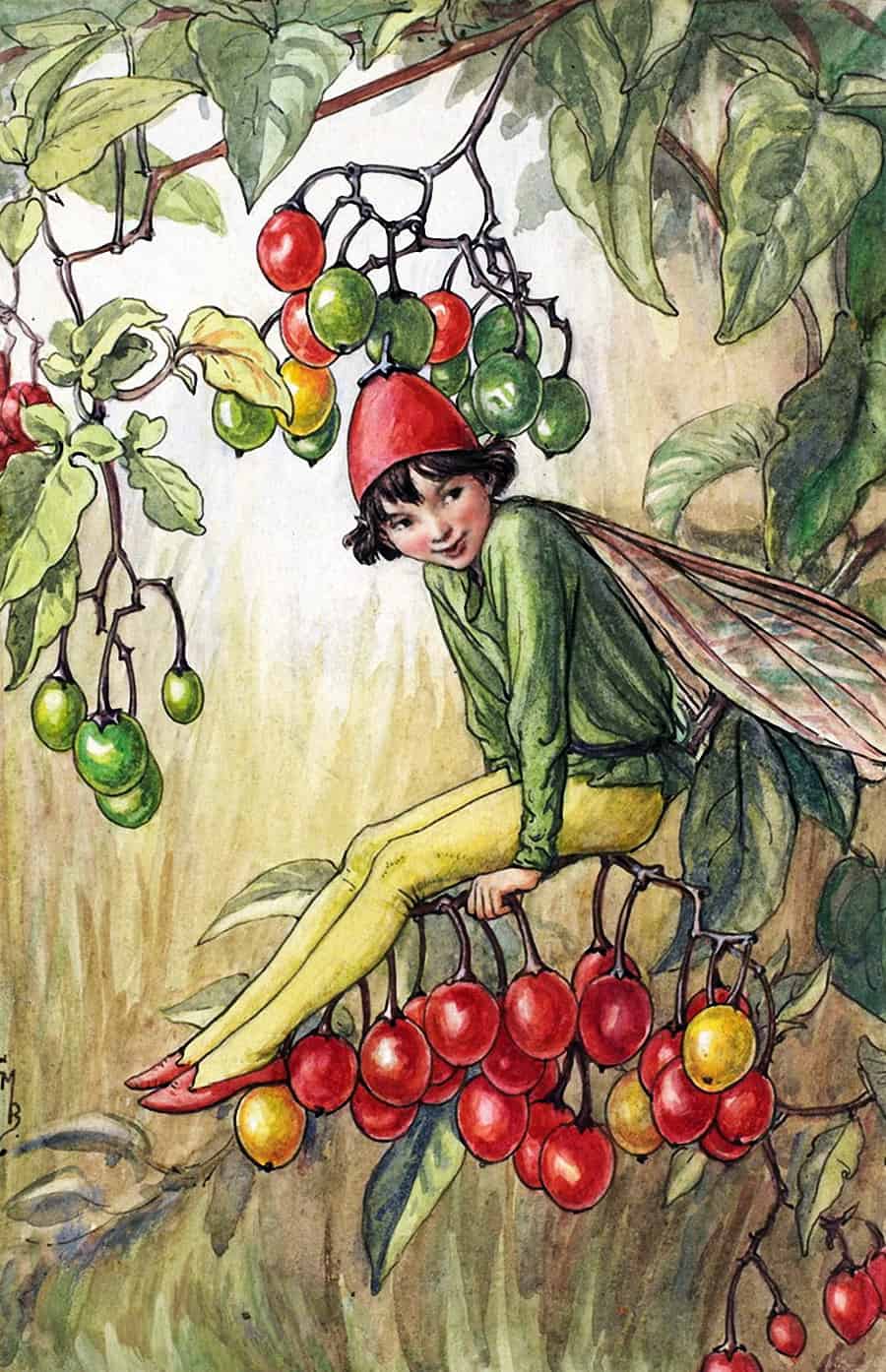

Machen manages to achieve, only a few years before the comfortably kitsch flower fairies of Cicely Mary Barker, the singular feat of rendering fairies terrifying…

The fear that Machen summons up with regard to meeting the fairies among the trees was long one of the reasons why rationalist opponents of such tales were so vociferous in wishing them stamped out. Fairy tales were bad for children, because they frightened them. Worse, they were scared by unrealities that could not be, by witches, ogres, dragons and wicked pixies. A course of no-nonsense realism and facts was the required cure, not a giving over of the self to wild imaginings.

Between Terror and Kitsch

I am not so sure about Eleanor Farjeon (1881-1965), whose outstanding personal qualities may have caused her work to be valued too highly in her lifetime. She was prolific, and there were many collections of her verses, which were often rolled forward from one book to another. Her own choice from a wide span of her work was made in The Children’s Bells (1960). She wrote many fairy poems, poems of time and place and of the seasons. All were graceful and some were more than graceful; for instance, “It was long ago”, recalling an incident from the earliest misty edge of memory; or “Cotton”, which reflects Eleanor Farjeon’s special feeling for young girlhood. Yet already it seems that time may be closing gently over much of her work.

Written for Children, John Rowe Townsend

Rose Fyleman (1877-1957) is remembered for a single line: “There are fairies at the bottom of our garden!” Her arch little verses were highly popular in the 1920s, and she produced several “fairy” collections, all of which are out of print. She must however be given the credit for having induced A.A. Milne to try writing verse for children.

Written for Children, John Rowe Townsend

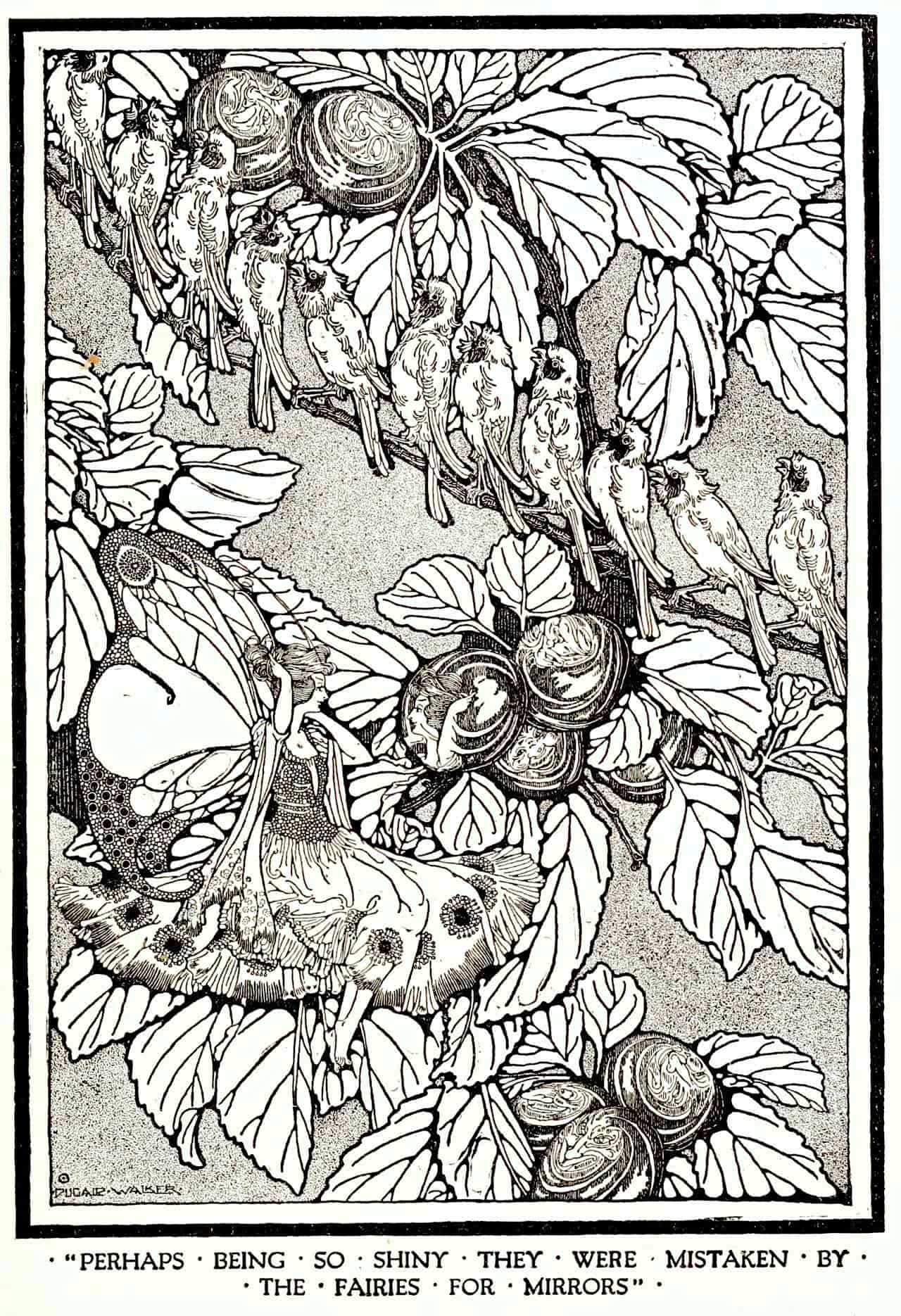

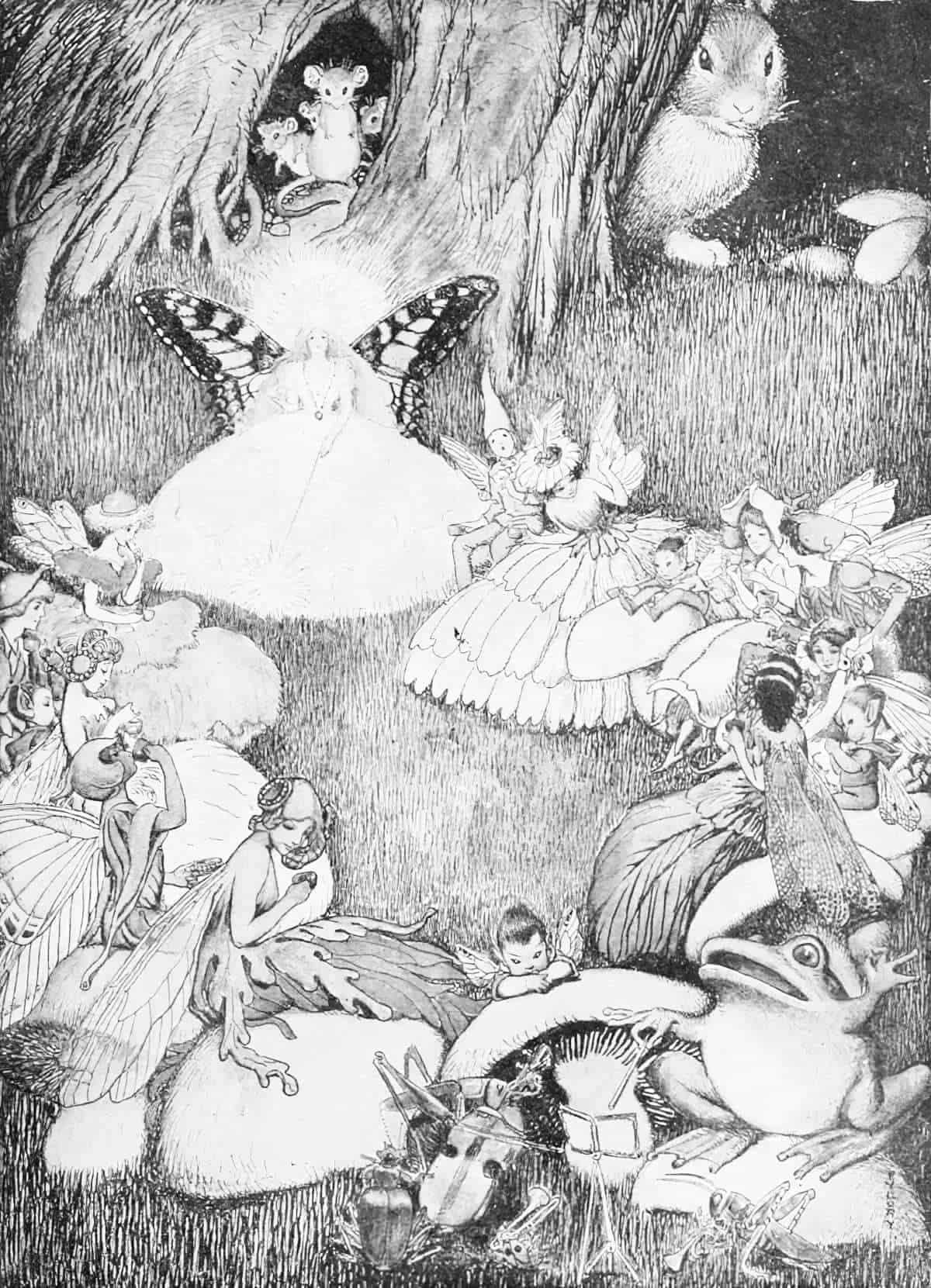

Fairies and Flowers

FURTHER READING

A List Of Modern Books That Are Either A Retellling Of A Fairy Tale Or Have An Accurate Use Of Folklore from Faery Tales & Nightmares

Fairies and Fairy Stories: A history by Diane Purkiss

Katharine Briggs’s Dictionary of British Folk Tales In The English Language (1970-71) is a four volume encyclopedia which summarises all the fairy tales, novellas, animal stories, fables and legends collected in the British Isles.