Industrialization refers to the change from a society without machinery to wide scale development of industries. The time before The Industrial Revolution is called The Pre-industrial Era: hunting, agriculture, small scale production.

What are the four Industrial Revolutions?

1. THE FIRST INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

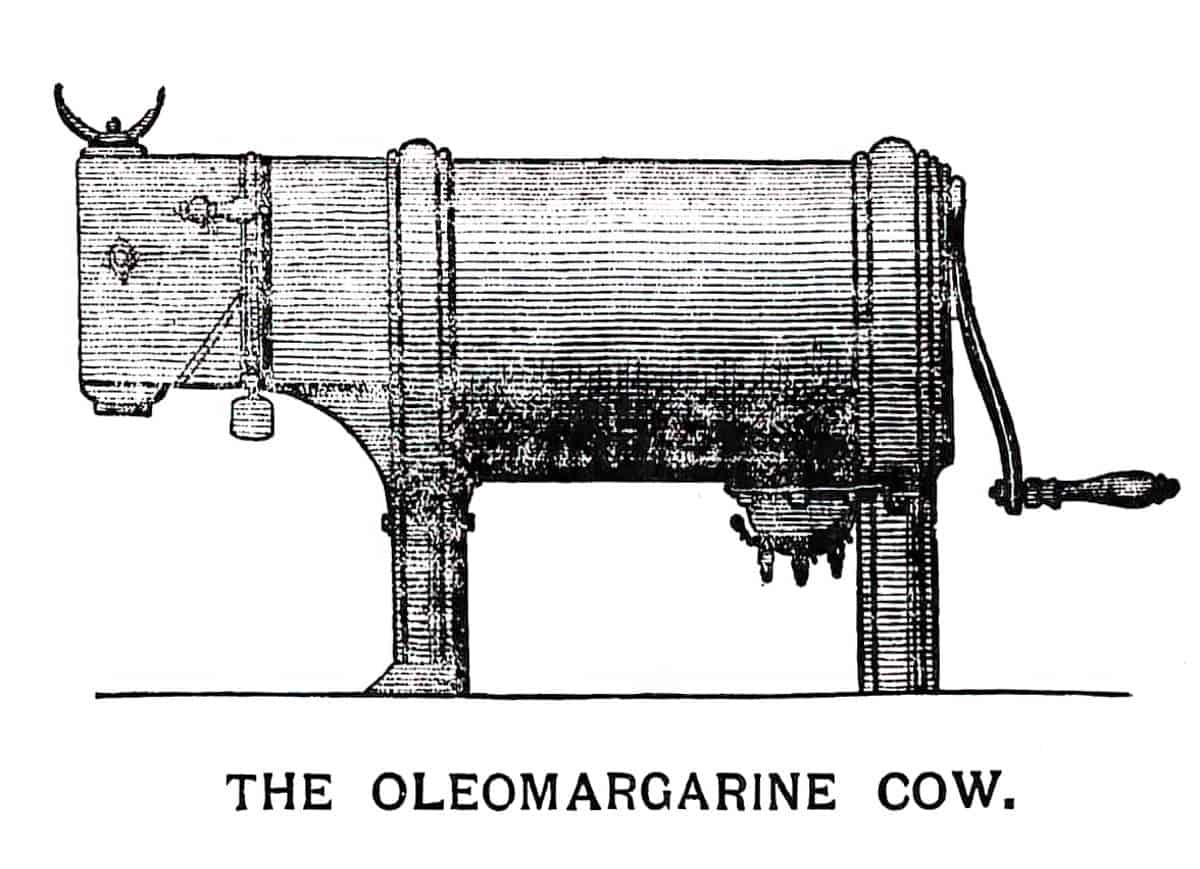

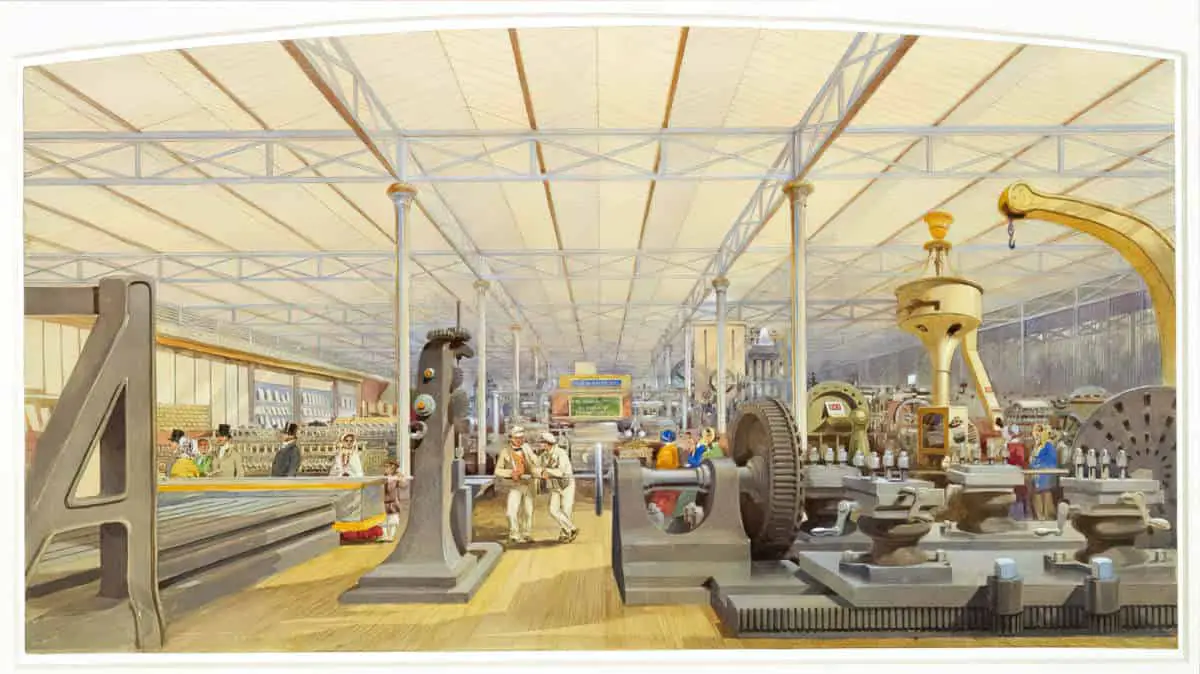

The (first) Industrial Revolution happened 1750-1850. It didn’t happen at the same time in every region. Countries rich in iron ore and coal were perfectly suited to factories and mass production. For these regions, the revolution happened early. Some say it began in 1780. This decade marked the introduction of machines powered by steam and water.

2. THE SECOND INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

A second Industrial Revolution broadly happened 1870-1914. These dates are not a hard line. In some places, it started twenty years earlier.

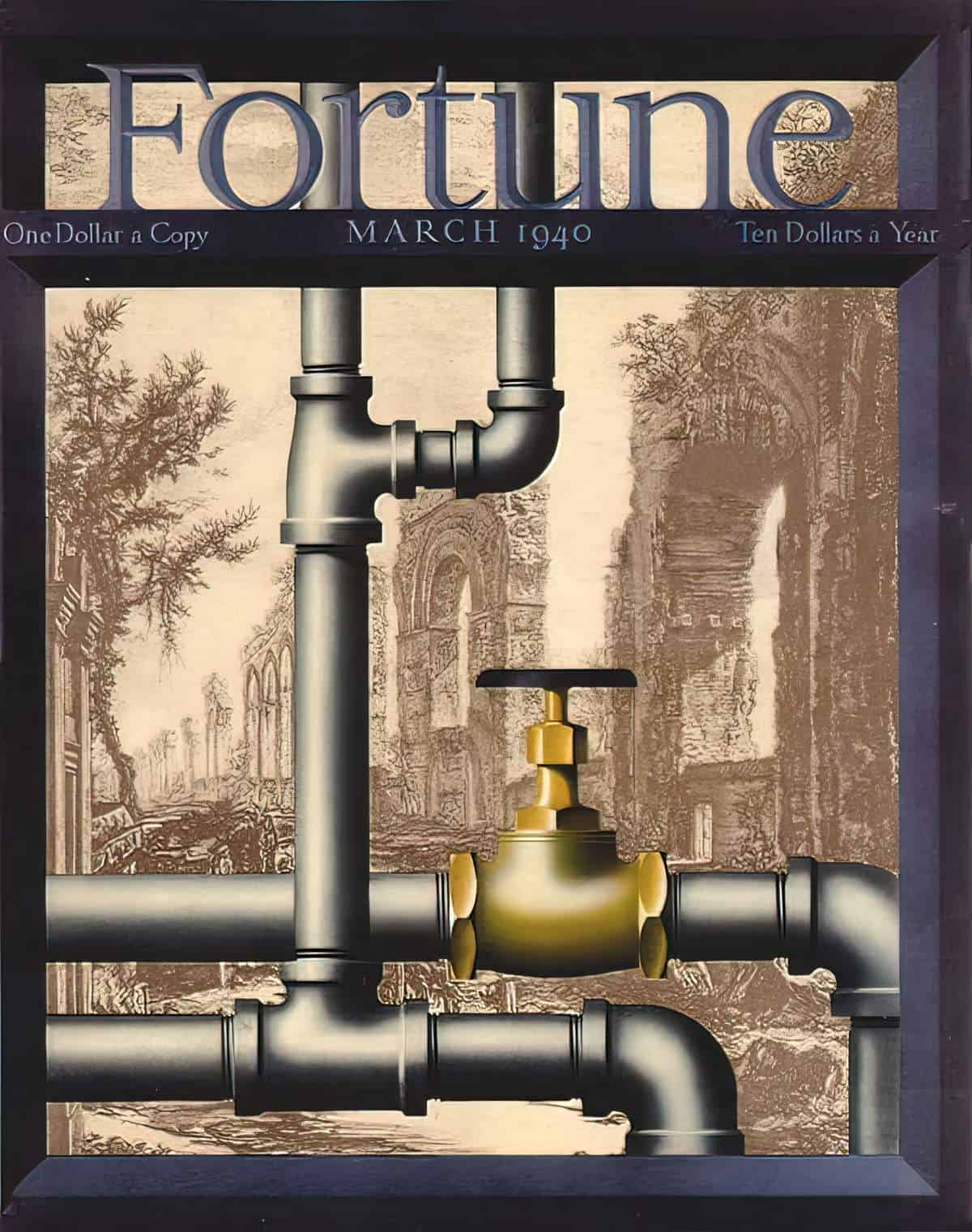

The second Industrial Revolution was marked by a widespread switch to electricity. Of course, not everything is powered by electricity, even now. Energy diversified. Aside from coal we now had: electricity, coal, steam engines, gas and petroleum. These sources of energy replaced a lot of human muscle power. Manual labour became less intense.

See also: A Brief History Of Home Lighting

We also got antibiotics. Antibiotics made many modern medical procedures possible, including cancer treatment, organ transplants and open-heart surgery. Before penicillin, hospitals were full of people with blood poisoning. A small cut or a scratch could kill you.

With these major advances of the second industrial revolution, life improved considerably for many people.

3. ELECTRONICS AND NUCLEAR

The third and fourth revolutions are sometimes bundled in together. Some people consider early 20th century electronics part of the Digital Revolution. Others keep micro chips and the Internet separate.

When scientists learned how to split the atom, nuclear energy thrust us into The Atomic Age. Now that nuclear weapons exist, the world will never be the same. We forget this now, but in the first three years of the 1960s, the world came very close to Armageddon. (Because of a bear.)

In better news, nuclear powers many regions. The first nuclear reactor to produce a usable amount of electricity opened in 1951. Opinions are divided over whether massive amounts of carbon-free electricity are worth the danger associated with nuclear power stations.

4. THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION

Some consider The Digital Revolution the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and separate from Electronics and Nuclear. Those who bundle the two together say this third, digital revolution began around 1900.

For those who consider it separate (and fourth), the digital revolution happened around 1980. Others say it happened in the 1970s.

During the digital revolution, computers replaced many ‘low-skilled’ tasks. There are now far fewer positions for people without tertiary qualifications. The digital revolution is all about ‘automation’. If processes have become automated, you’re talking about the digital revolution.

Regardless of the exact date, this is when Internet, mobile devices, social networking, big data, and computing clouds all combined to revolutionize how we work and how much we produce.

Artificial intelligence and big data go together.

What is big data? Big Data (BD) is extremely large data sets. These sets can be analysed by computers to reveal previously invisible patterns and trends. Few of us really grasp how quickly we can now gather data. Much of the data that was created in the world was created in the last few years. (The exact calculations depend on who you ask.)

5. THE FIFTH INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Some commentators think the world is entering a fifth Industrial Revolution, sparked by the 2019 corona virus pandemic and climate change.

We are now entering the age of artificial intelligence. As just one example, 2022 has been a big one for graphic artists with the release of Stable Diffusion. This AI is not yet putting artists out of work, but the technology is advancing so quickly, it’s hard to imagine it won’t.

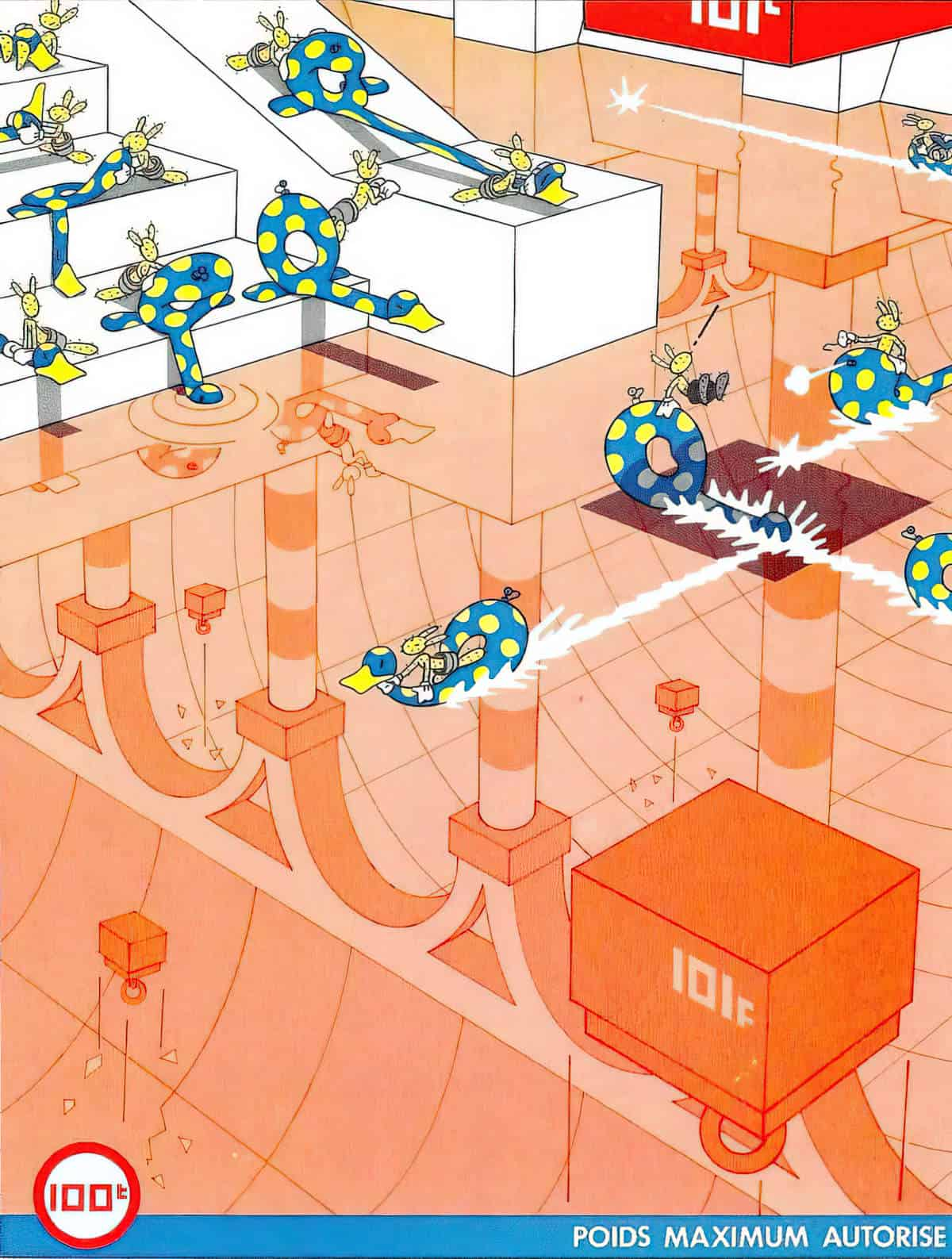

A fifth industrial revolution will involve robotics, drones, 3D printing, The Internet of Things (IoT) and digital platforms.

The Internet of Things: The proliferation of wireless networks. An expansion of the Internet away from designated ‘computers’ and into everything you can imagine. Basically, more and more things will become connected. Embedded sensors will exchange data. We already see this in smart appliances, smart security systems etc.

With more data, city planners can ease congestion and plan for population changes. Smart lighting can save energy. We will get more notice before natural disasters and personal health events. Vehicles will be driven by computers and we will (eventually) see fewer deaths on the roads. We’ll have robotics to assist in home care. We can eventually go cashless.

Why Do Major Revolutions And Disaster Go Together?

What’s the corona virus and climate change got to do with propelling us into a new era?

Anything that threatens public health leads to social unrest. People have a very low capacity to tolerate hunger, in particular. When large numbers of people don’t have enough to eat, they together make change happen. Ditto for when their family and friends are dying at alarming rates.

How Did Life Change During The Industrial Revolution?

INDUSTRIALIZATION CASE STUDY: WALES

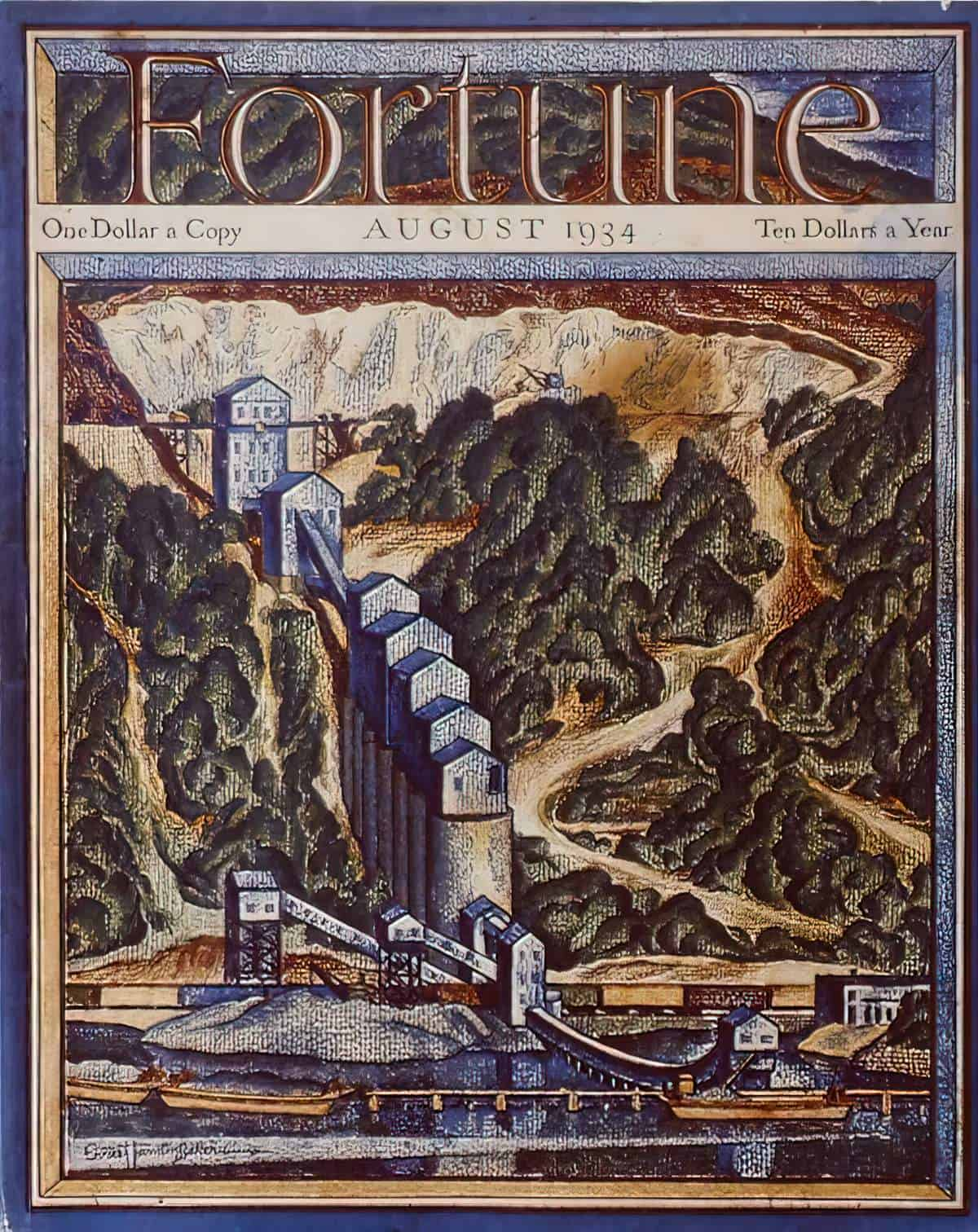

Wales was one of the first countries to enter the industrial revolution. Previously a quiet, rural place on the edge of the United Kingdom, Wales suddenly became a key centre of the British iron industry.

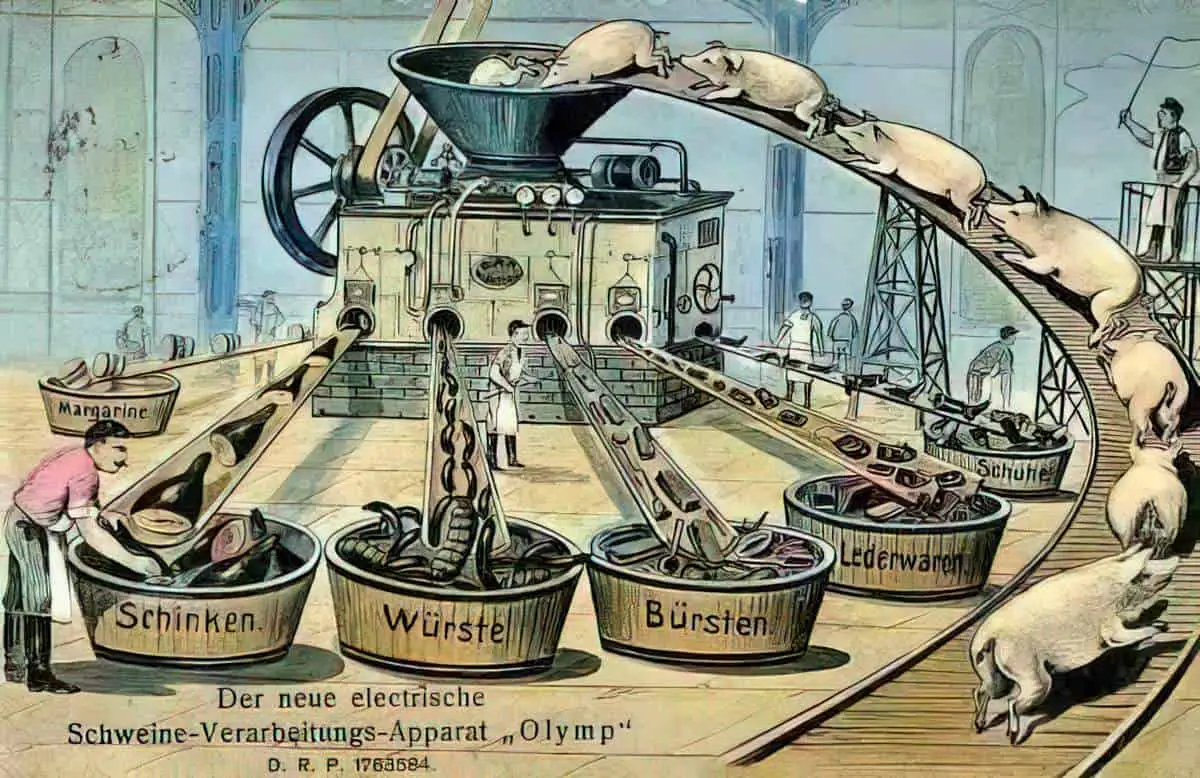

Wales was rich in both iron ore and in coal. Welsh coal burns at a very high temperature, which makes it high quality. High quality coal gives off little smoke.

The demand for iron was partly driven by the Anglo-French war between England and France in 1778. During this war, iron was needed to make canons. Coal was also required, because coal stokes furnaces which melts the iron for canons.

Because Welsh coal burned so cleanly, warships powered by Welsh coal weren’t easily seen from a distance. There were no billowing plumes of smoke to blow their cover. For a time, the Royal Navy would only sail on Welsh coal.

In the 19th century, coal became more important than iron as the major Welsh export. Coal was needed to power everything, including steam ships and railways.

Regions of the world rich in ‘clean-burning’ resources were perfectly suited to industry. There, population growth followed. Wales is an excellent example of industrial-powered population growth. Before the industrial revolution, the population of Wales was half a million. Just one century later, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Welsh population was well over two million. In just 100 years, the population had more than quadrupled.

When populations grow this rapidly, tiny villages suddenly become towns. When communities grow too fast, there’s no infrastructure to support people — not enough housing, no sewerage, no good transport network in and out of the town.

And in countries like Wales, where industrialization and capitalism go together, wages can fluctuate quickly and significantly. Wages can go up quickly, and fall just as quickly. When wages fall and workers become hungry, people become angry. They rebel en masse.

Wales had the Rebecca Riots in the late 1830s and early 1940s because people were suddenly being charged tolls to get to their own farms. Other less specific riots tend to be about general unfairness around falling wages. Factories make a few at the top very wealthy. The people doing the grunt work are considered tools. Without laws to protect workers, and strong labour unions, humans across the globe are exploited by corporations. That’s how the machinery works.

INDUSTRIALIZATION AND INQUALITY

The scientific advance upon nature led to industrialization, which is … a mixed curse and blessing; and industrialization led to the expansion of capitalism. The backbone of capitalism was the middle class family, with its objectives of ‘the continuity of the male line, the preservation intact of the inherited property, and the acquisition through marriage of further property or useful political alliances. These values — power through property possessed by males — intensified the stratification of classes: the rich had more ease and luxury than any but an oriental despot had possessed in earlier ages, and the poor were more utterly dispossessed, vulnerable, destitute — landless, homeless, and starving, than they had been under feudal regimes.

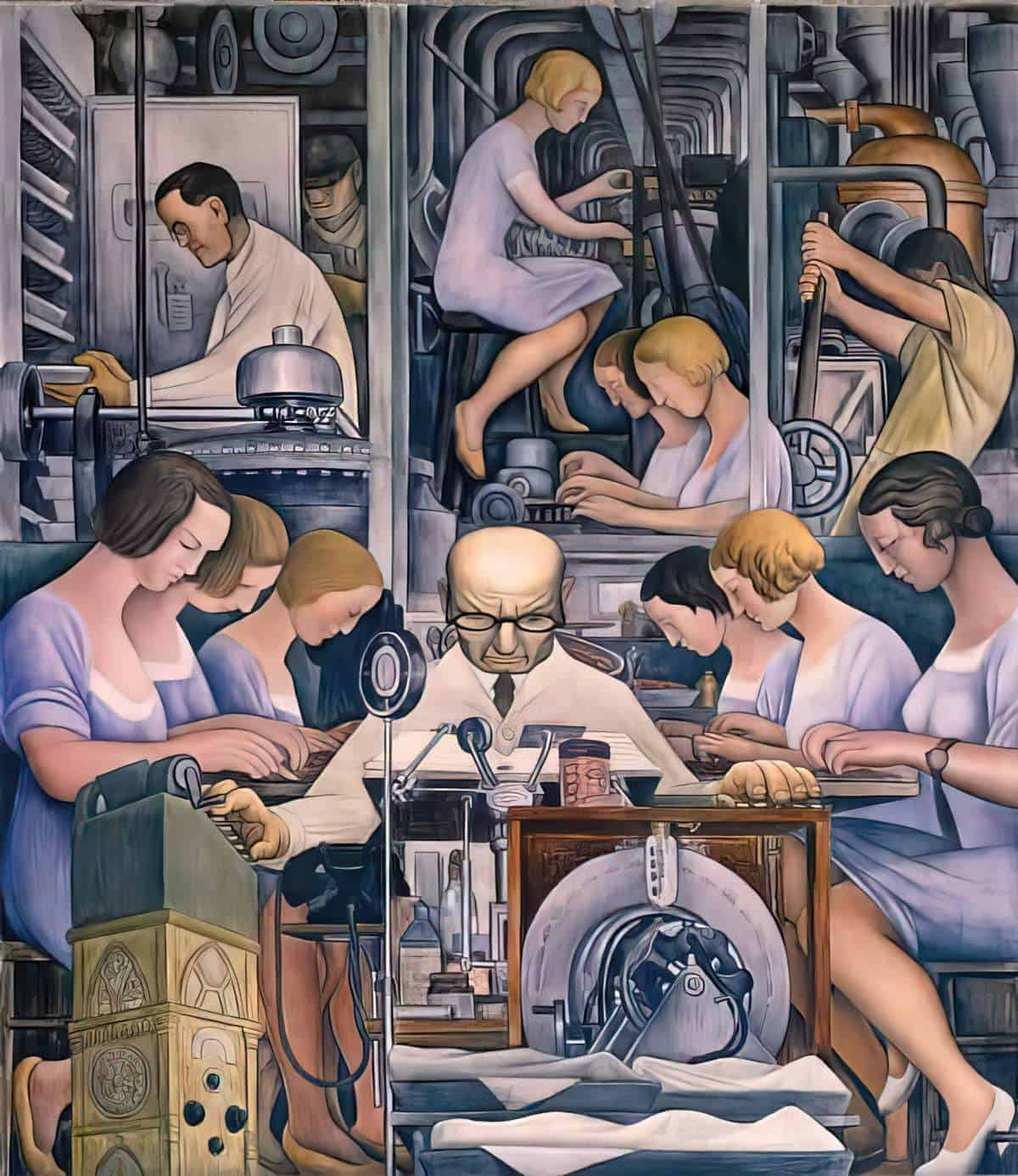

Industrial capitalism carried to an extreme the tendencies of instrumentalism. Having lost the land they used to work, the communities in which they used to live, people were forced to sell themselves, their labor power. For the first time, masses of workers were deprived of any control over the production of what they needed: they could not choose what to make, when to make it, or jow to make it. Workers became, for capitalises, merely another factor of production, along with raw materials and machinery. Moreover, if the capitalist wants to survive, he must act ‘rationally’; that is, he must treat workers as means to his end (profit) rather than as fellow human beings.

Imperialism — capitalism extended to alien peoples — developed naturally enough, and a new class of ‘nonhumans,’ indigenous populations, was added to Western consciousness. Whether they were seen as innocents in need of Western ‘light,’ or as expendable resources of exploitation, indigenous populations presented themselves to the imagination of the power-worshipping West as a ‘free’ territory for the exercise of Western ‘virtues’ (among which was acquisitiveness). […]

Like early industrialization, like early capitalism, imperialism was described at first in terms of expansion and liberation of the human spirit and improvement in material circumstance. But all new waves of patriarchal thought are described in this way, and are no doubt conceived of in this way by those who incite them and those who are persuaded to follow them. Even small revolutions are fought on grounds of liberation.

Beyond Power: On Women, Men & Morals by Marilyn French p 107

Beverly Gordon writes about the conflation between women and their houses and the new expectations heaped upon housewives in the industrial era.

How did this conflation between animate woman and inanimate room come about, and why was it so strong in the decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century? It was largely an outgrowth of women’s ideal role in the culture that was created by industrial capitalism. An almost obsessive preoccupation with proper appearance was characteristic of the nineteenth century, a time of rapid and far-reaching social change fostered by unbridled industrialization and urbanization. Although upward social monility was far from guaranteed, its success was apparently common enough by the middle of the century to support the popular belief that status was no longer ascribed as much as achieved. In a world of urban strangers, appearance beame ever-more important as the outward sign of such achievement. This in itself was not new; wealthy individuals since the Renaissance had been very concerned with the impression created by what they wore. However, this preoccupation was now extended to whole new categories of people, comprising the majority of the population. Individuals on nearly every step of the social ladder had to be vigilantly concerned with and conscious of their presentation of self. Dress–the decoration of the body–and interior furnishings–the decoration of the home–together formed what in more contemporary terms has been called the front that projected the desired image to the world at large.

Beverly Gordon, Woman’s Domestic Body: The Conceptual Conflation of Women and Interiors in the Industrial Age, 1996.

In The Remains of the Day, Lord Darlington (and later Mr Farraday) is having trouble domestics and they must be sourced from overseas at one point (the Jewish girls). This is because fewer women and girl were attracted to a life in service. Industrialization gave women more options. They might now work in a factory, which at least had set hours.

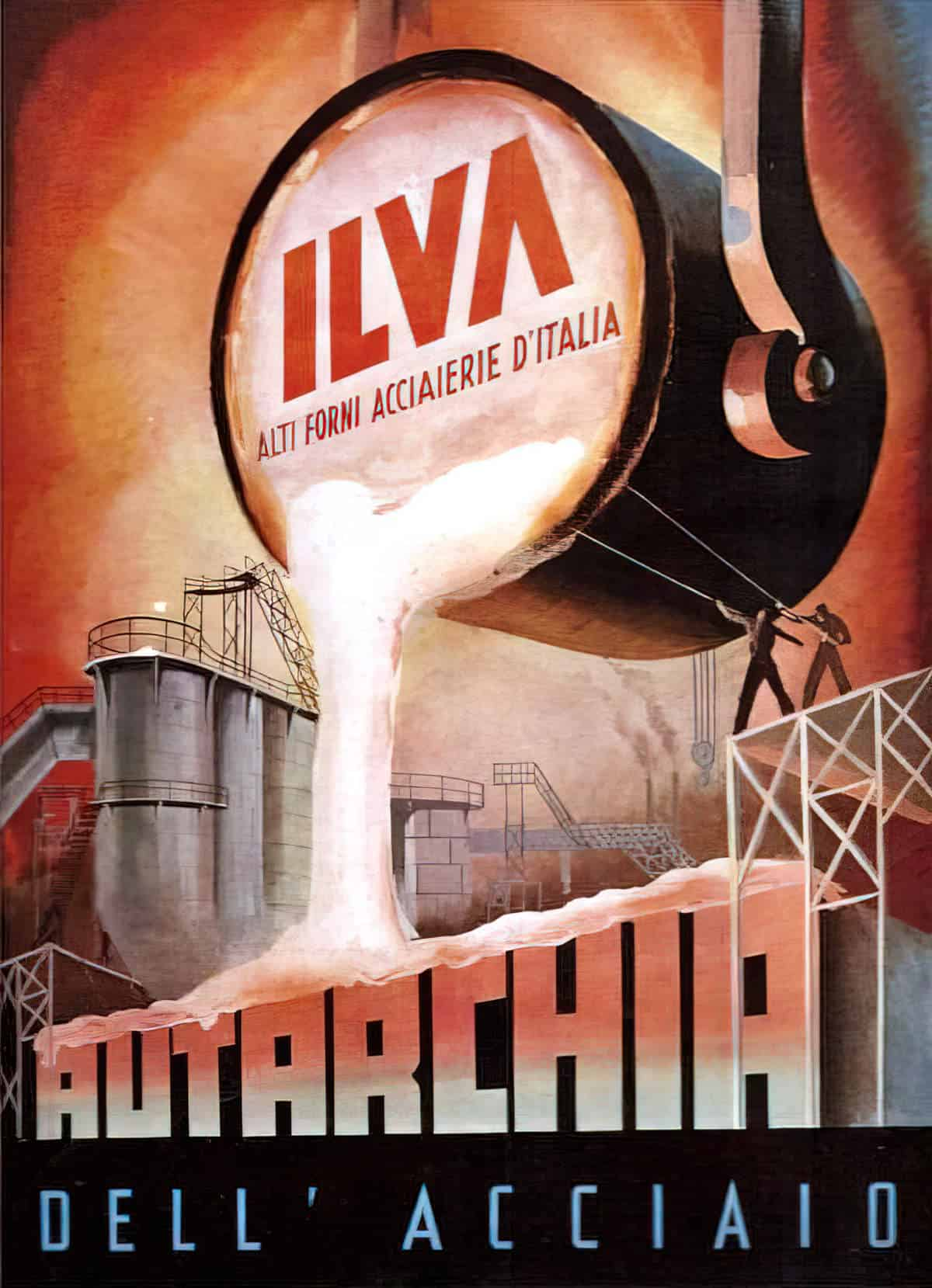

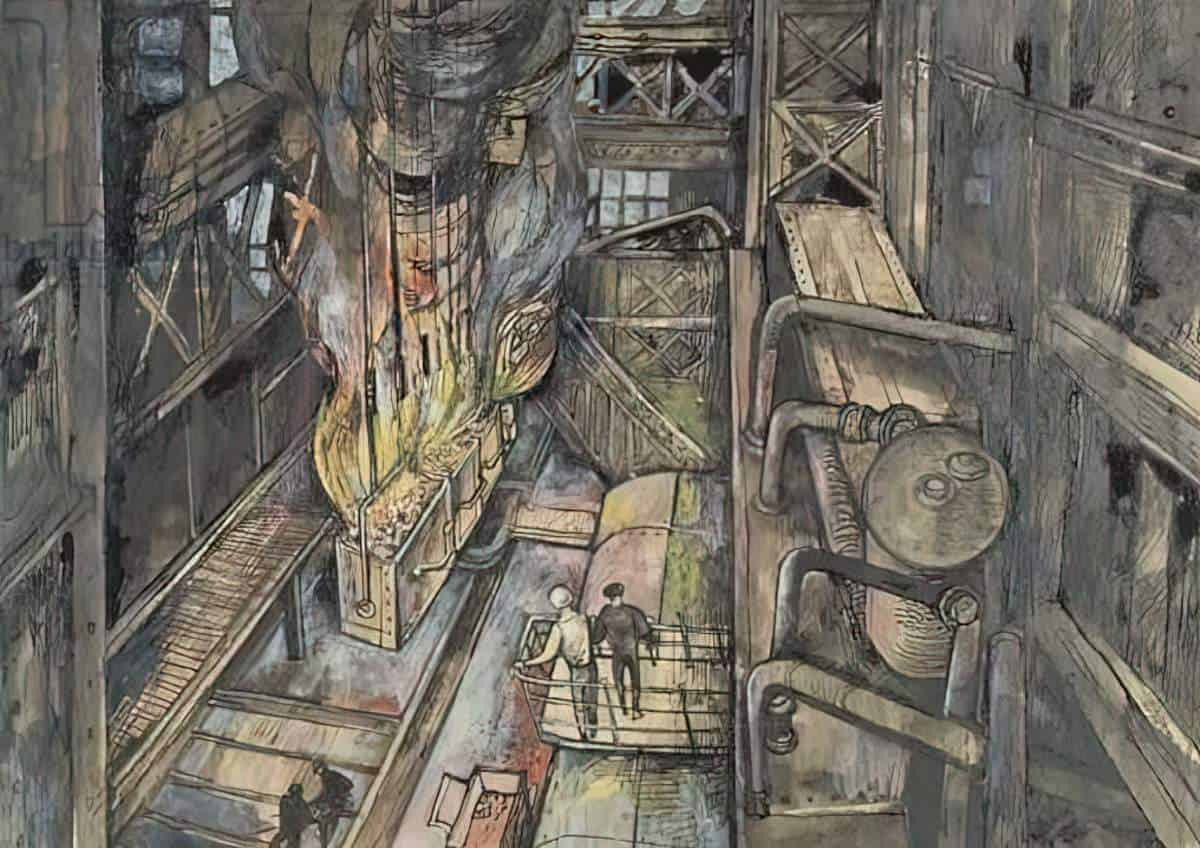

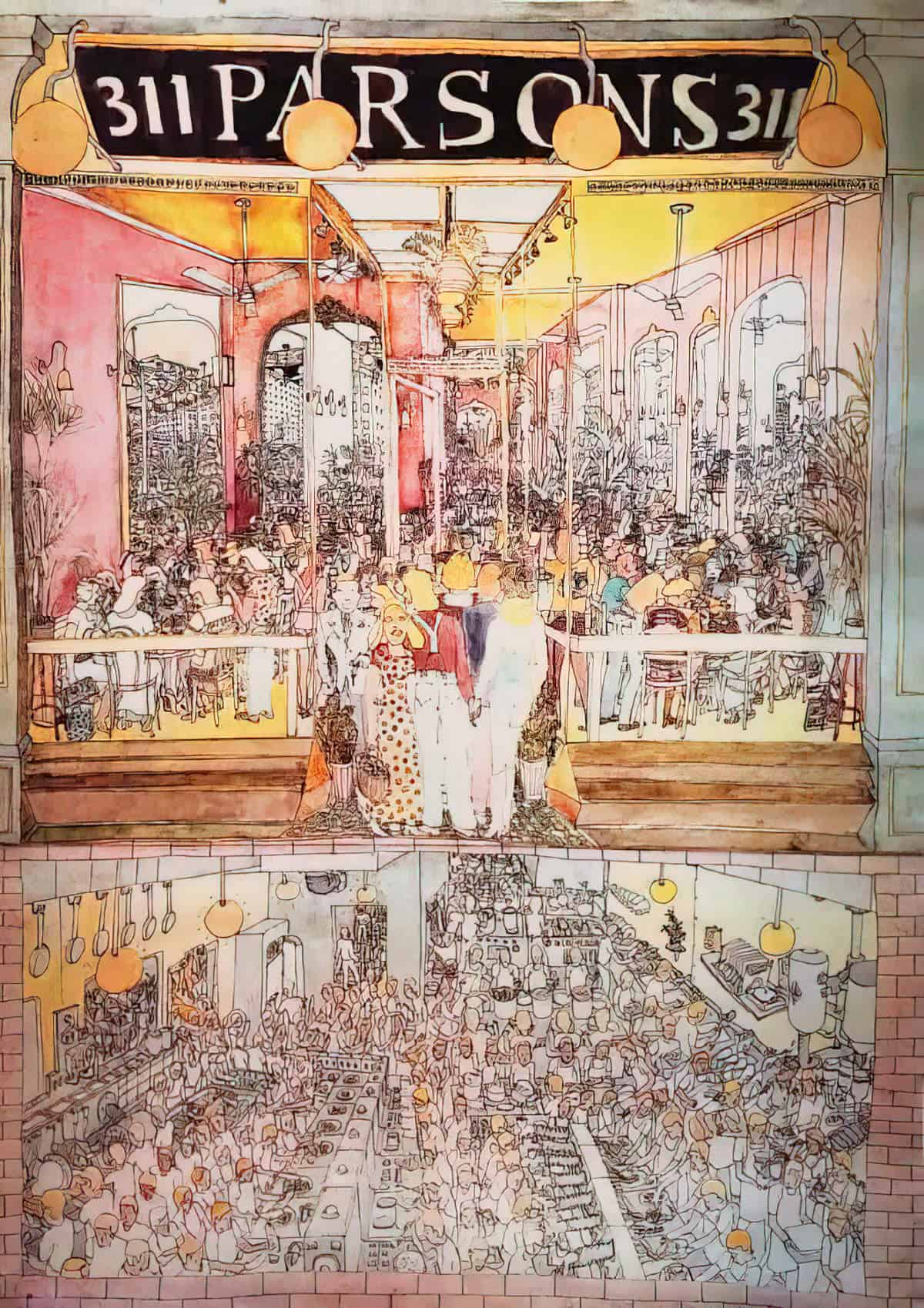

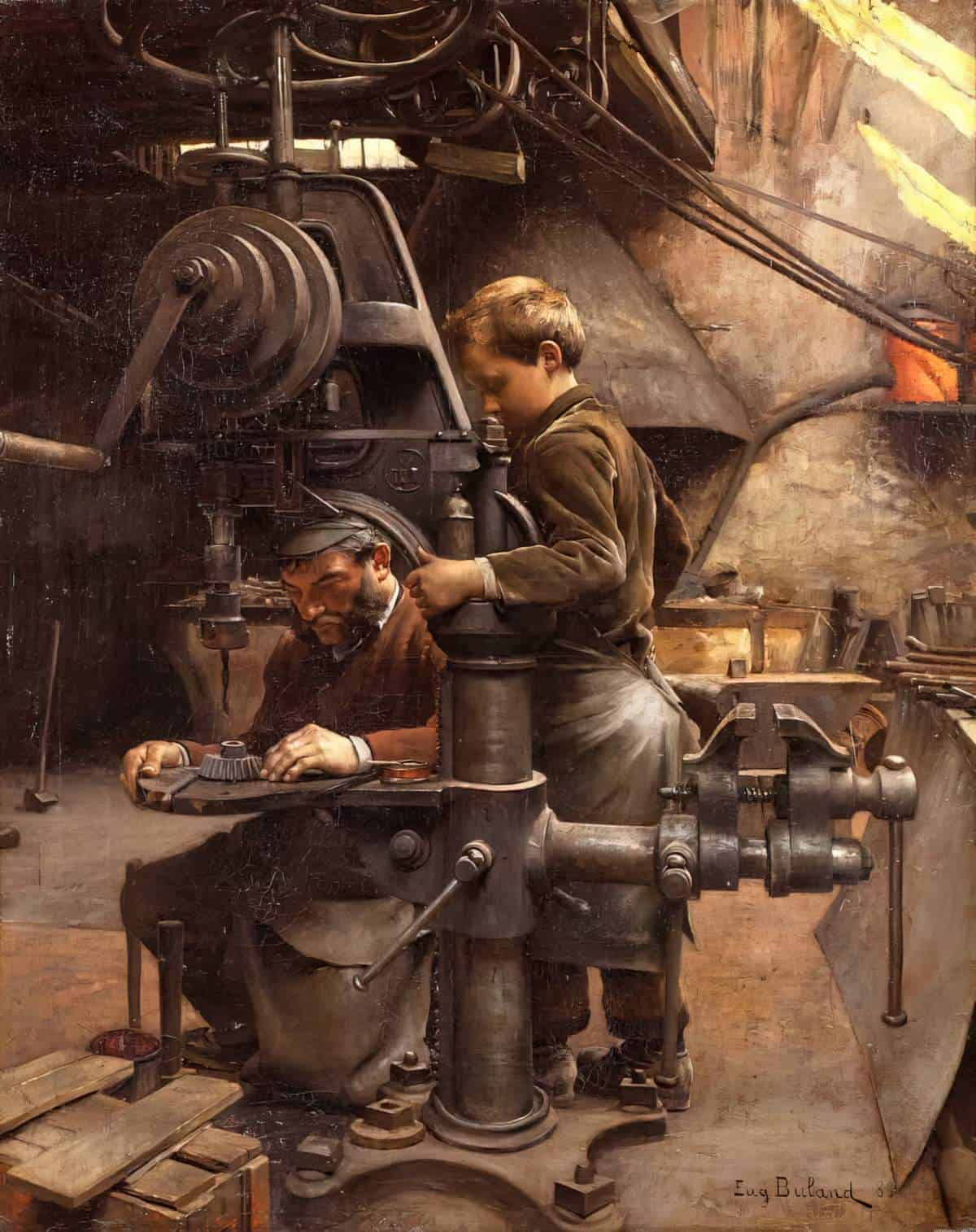

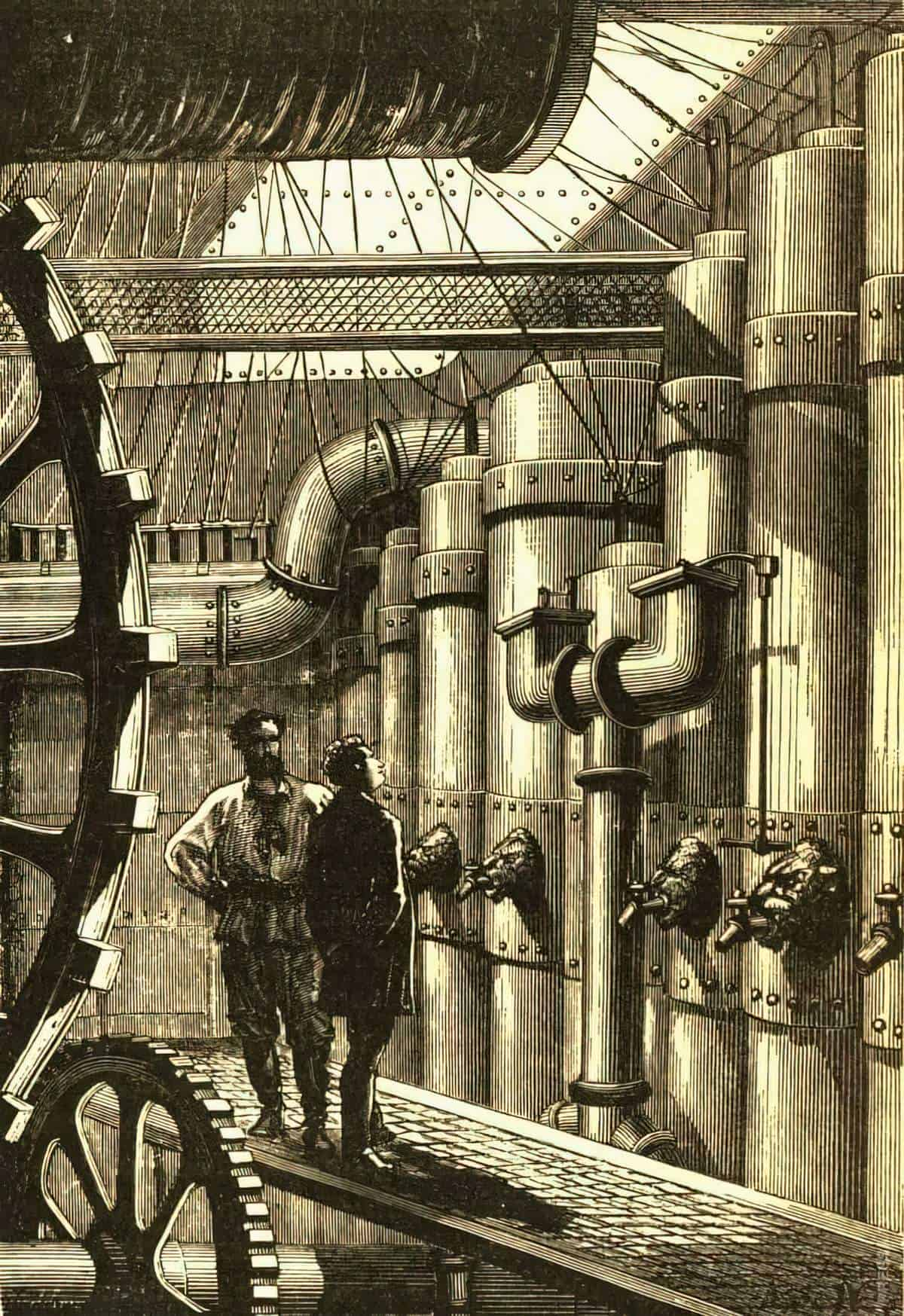

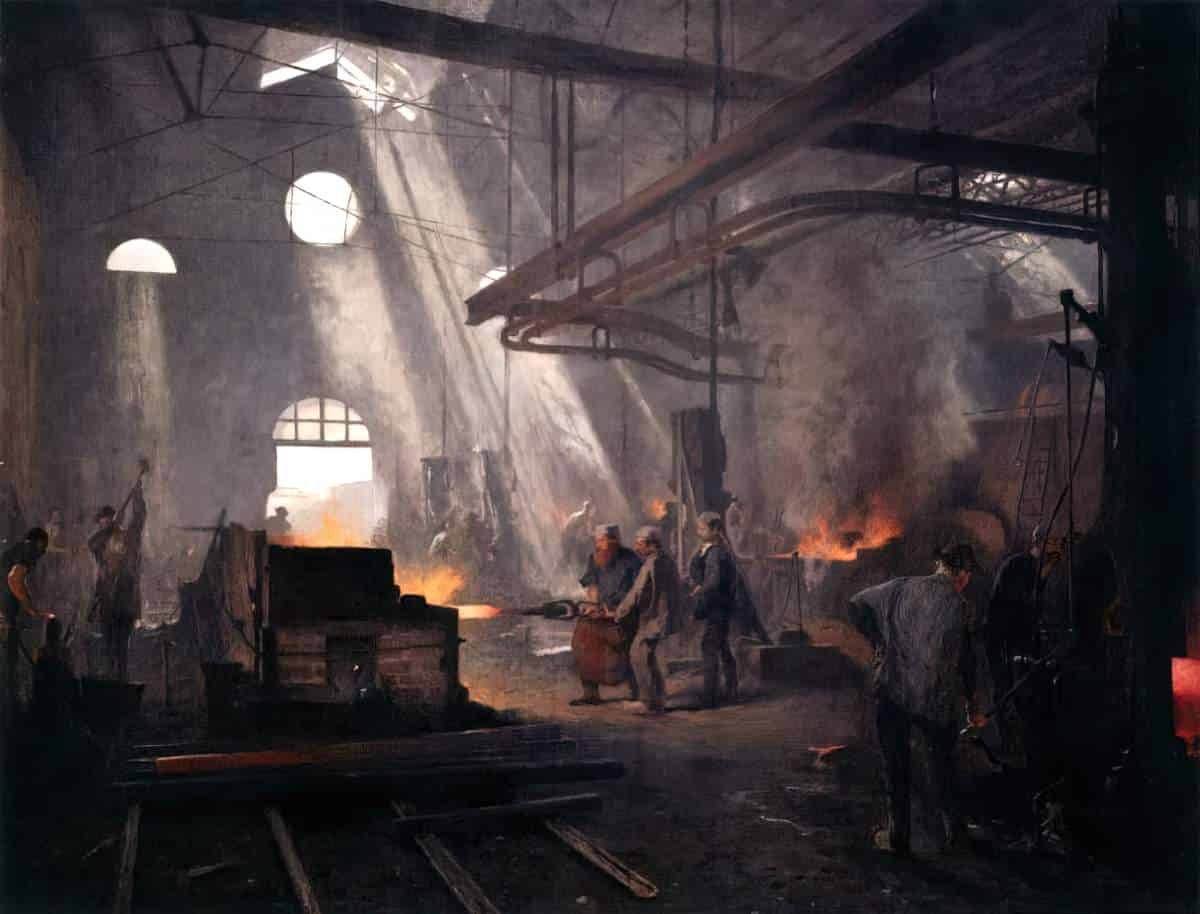

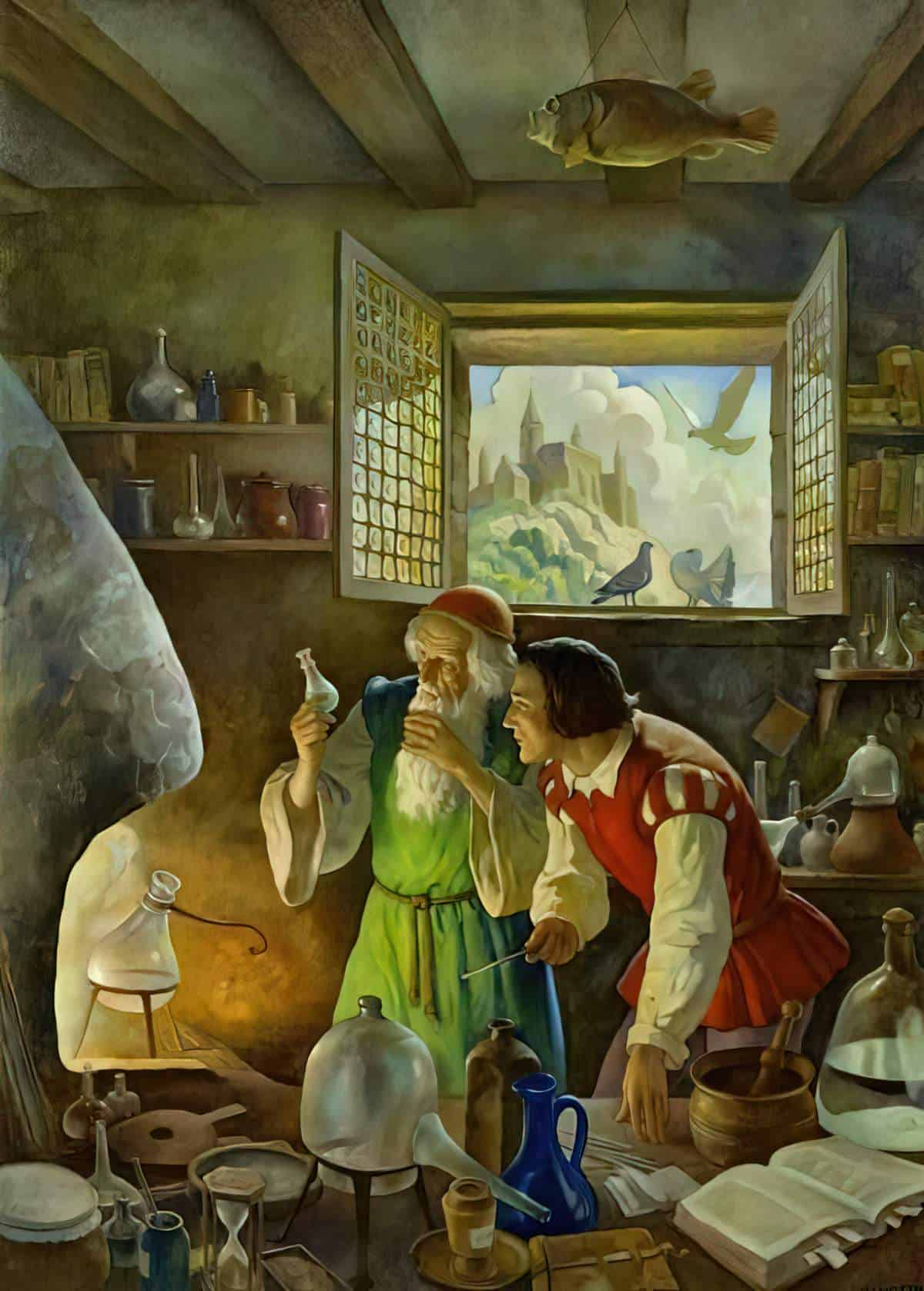

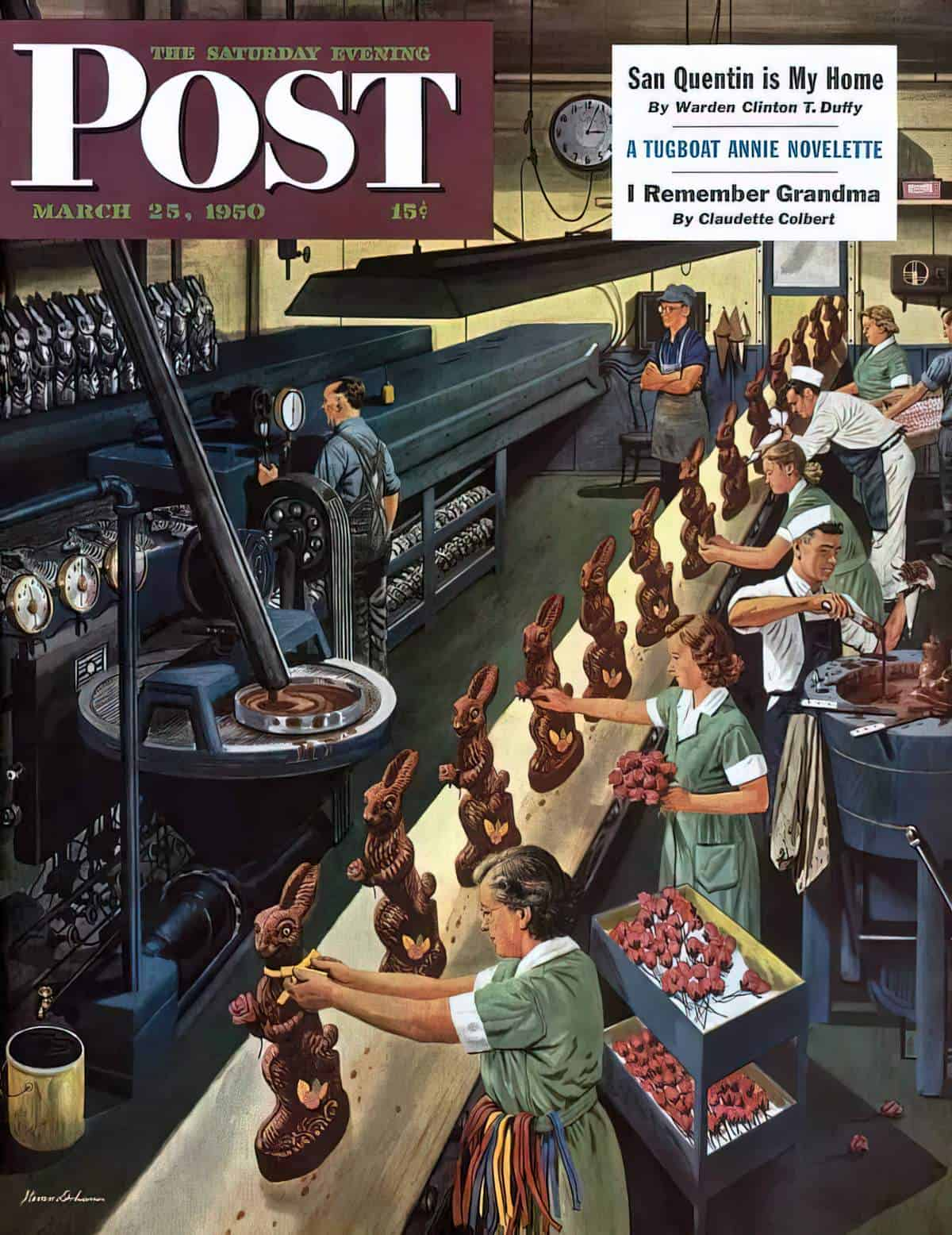

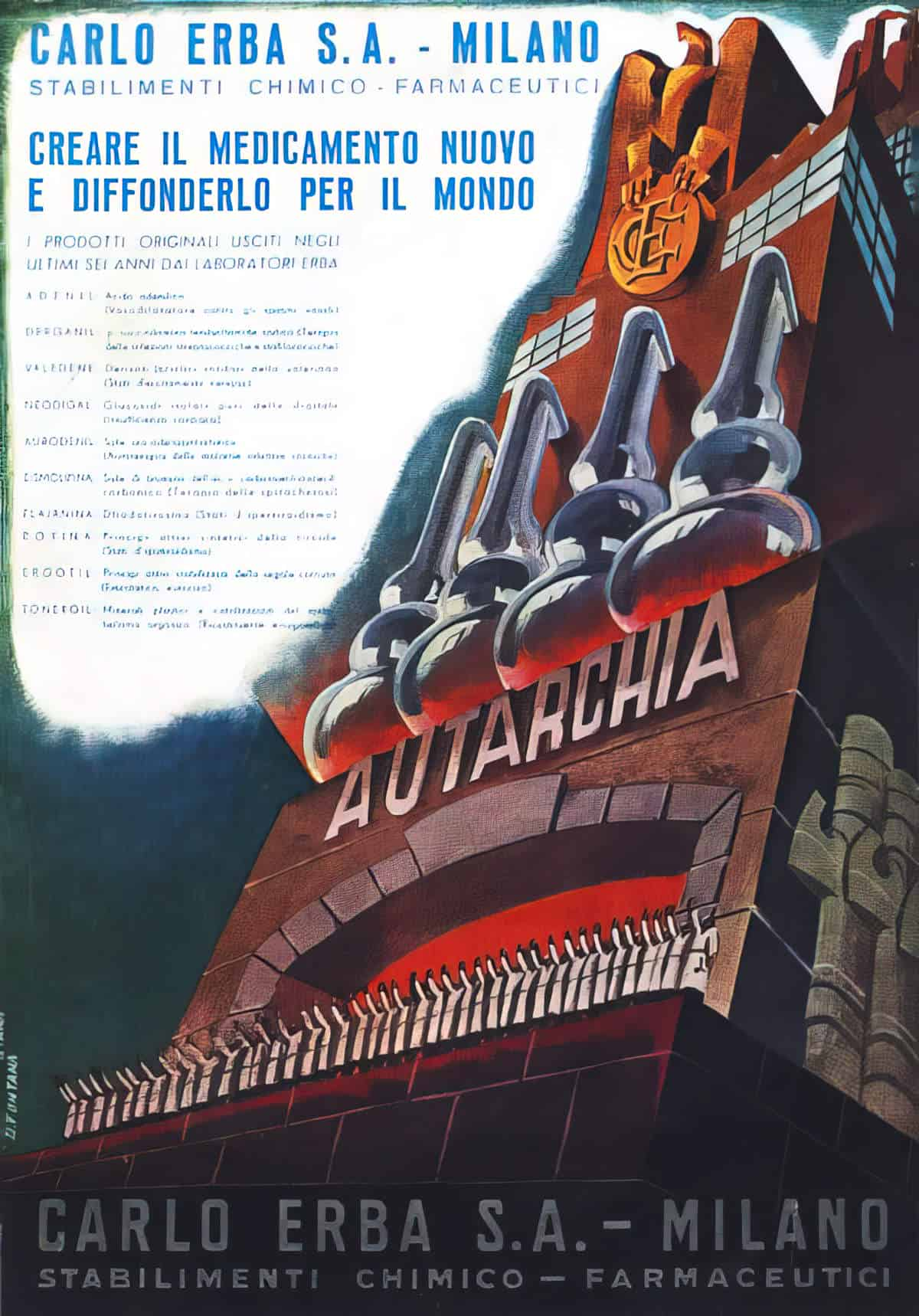

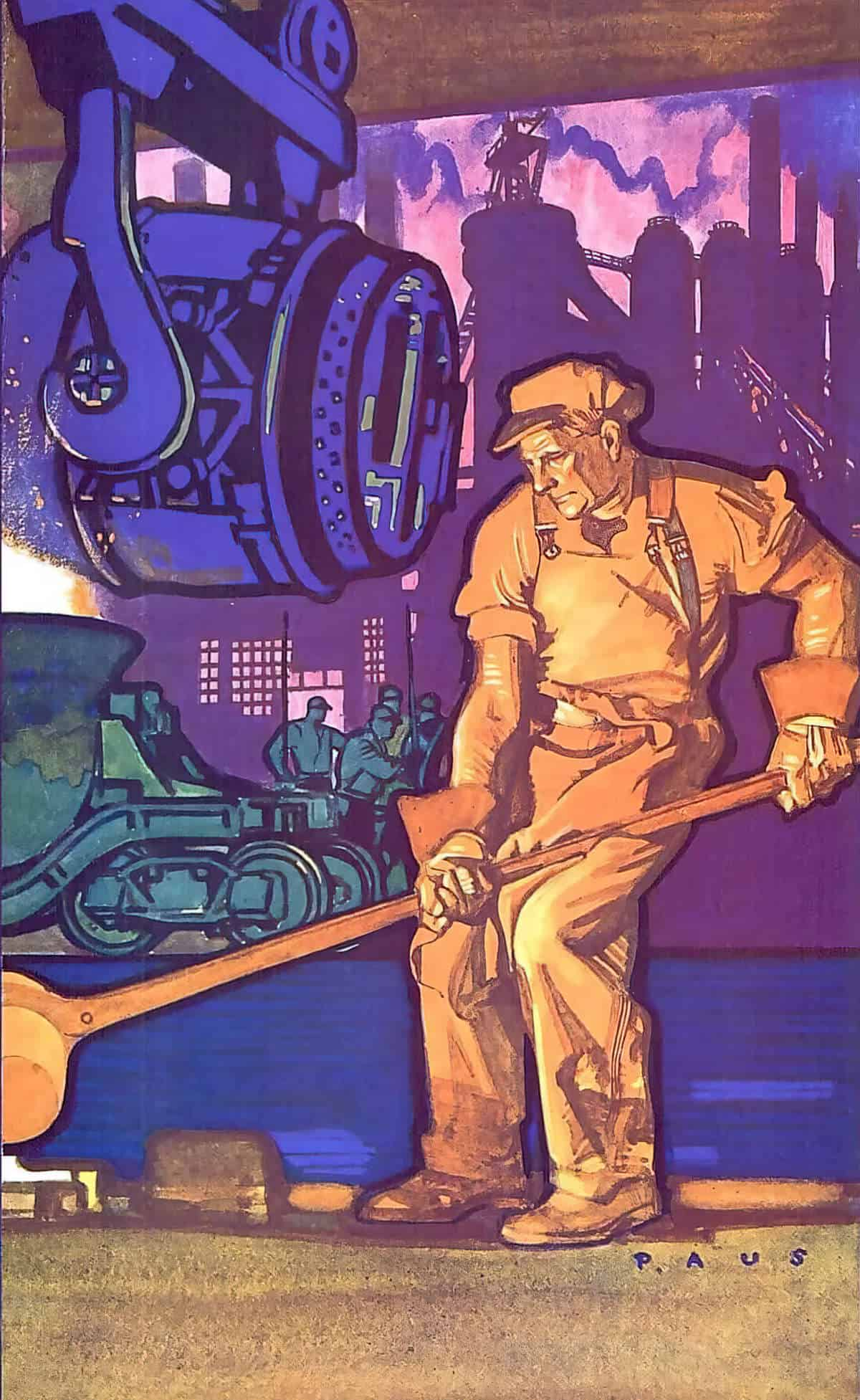

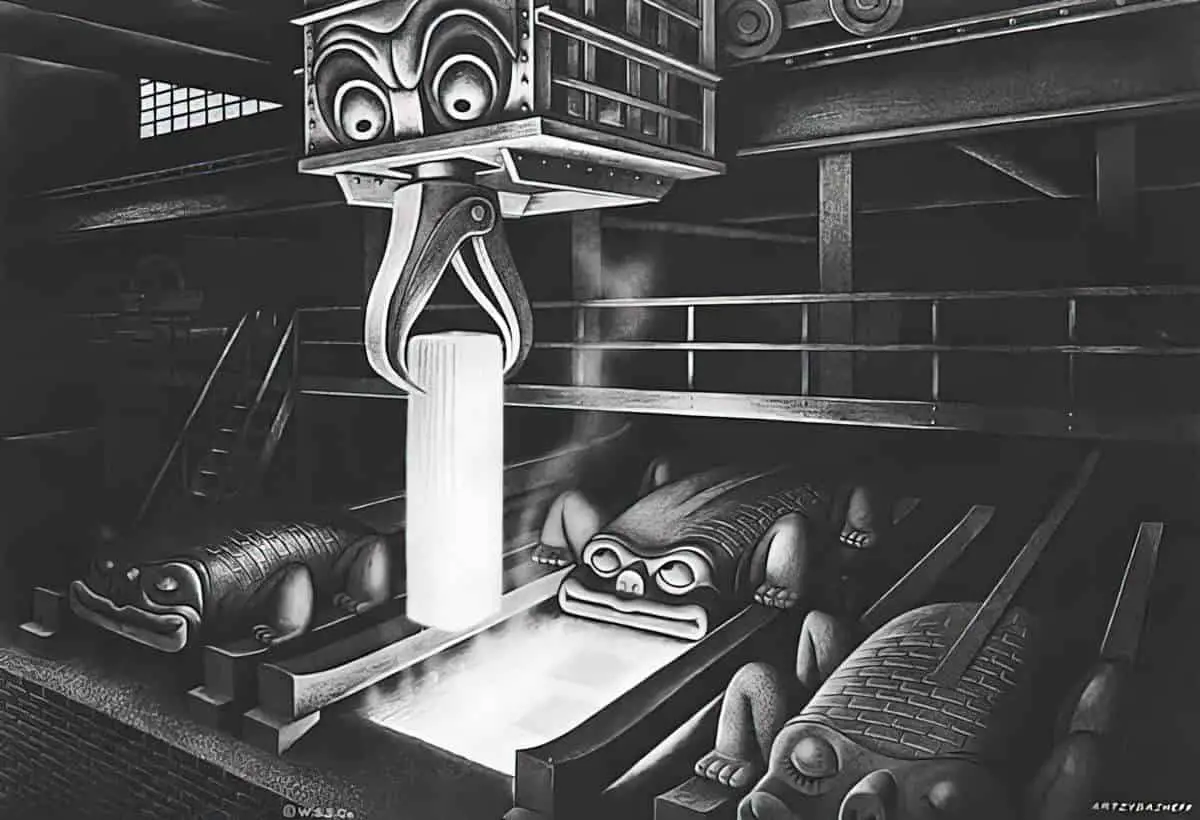

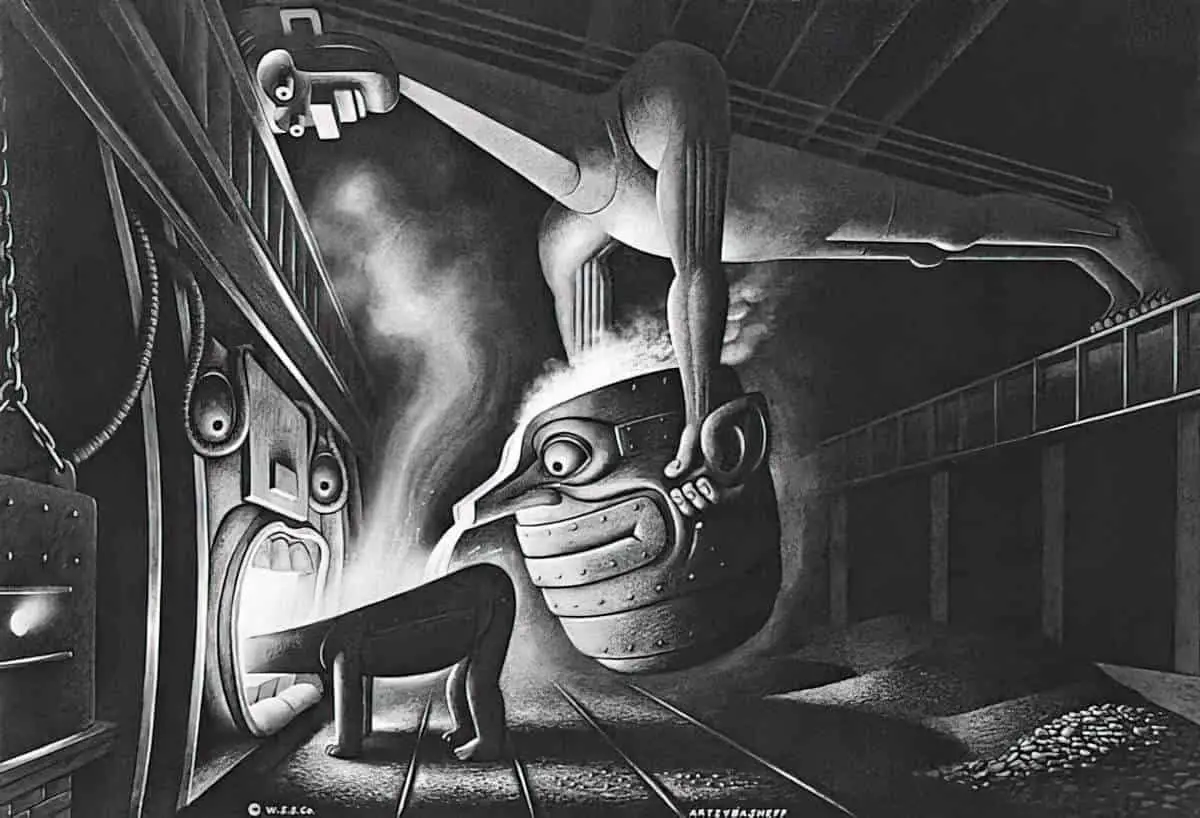

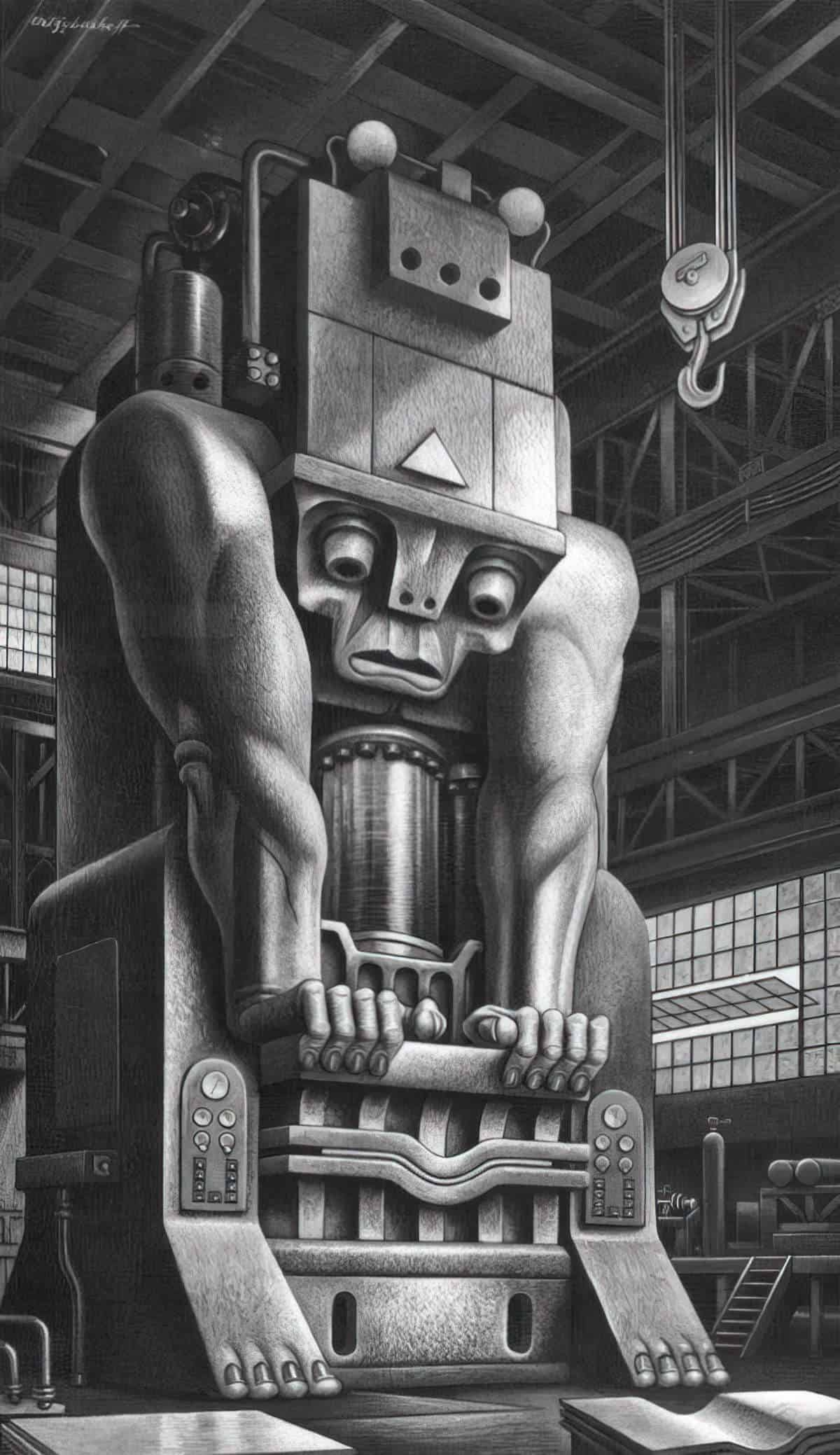

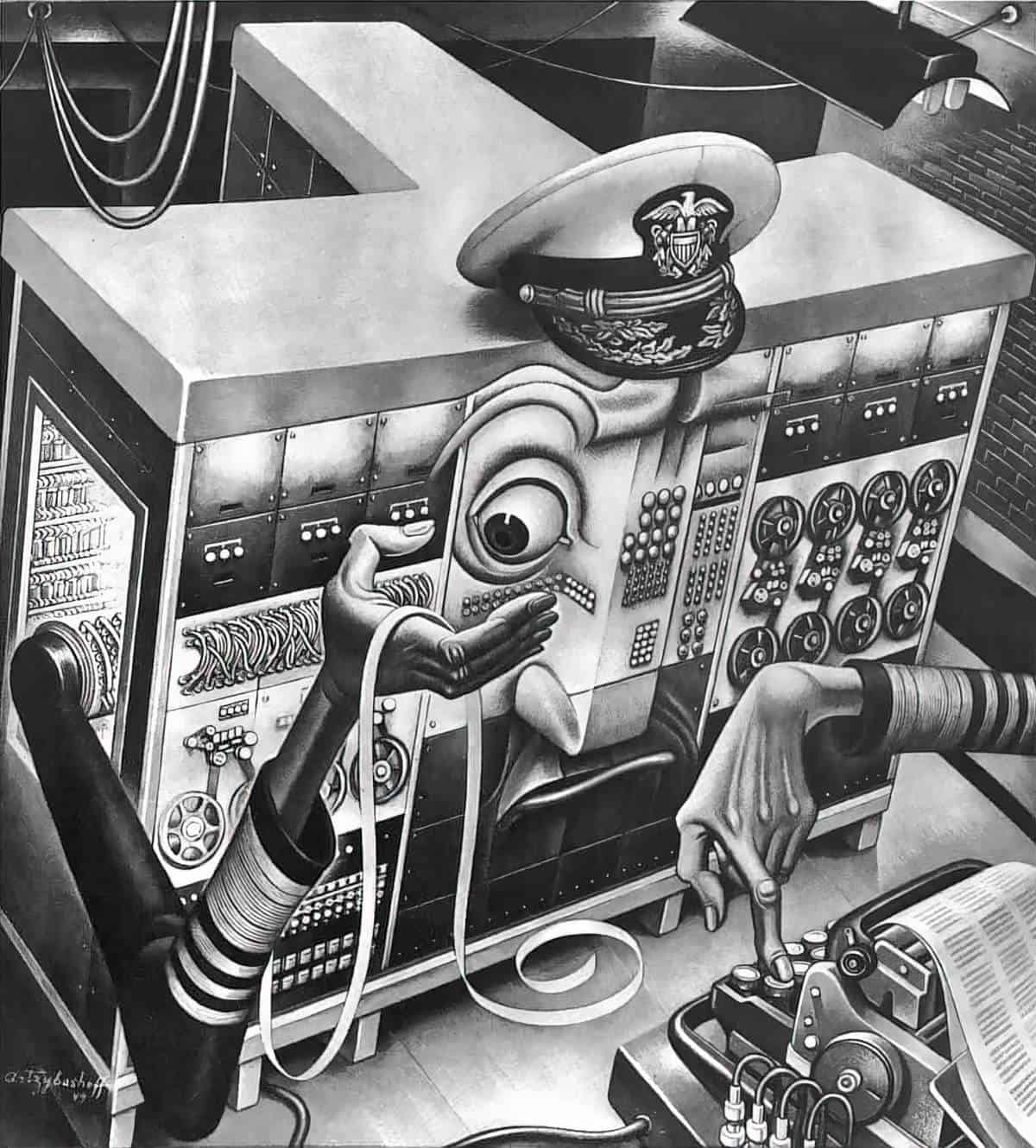

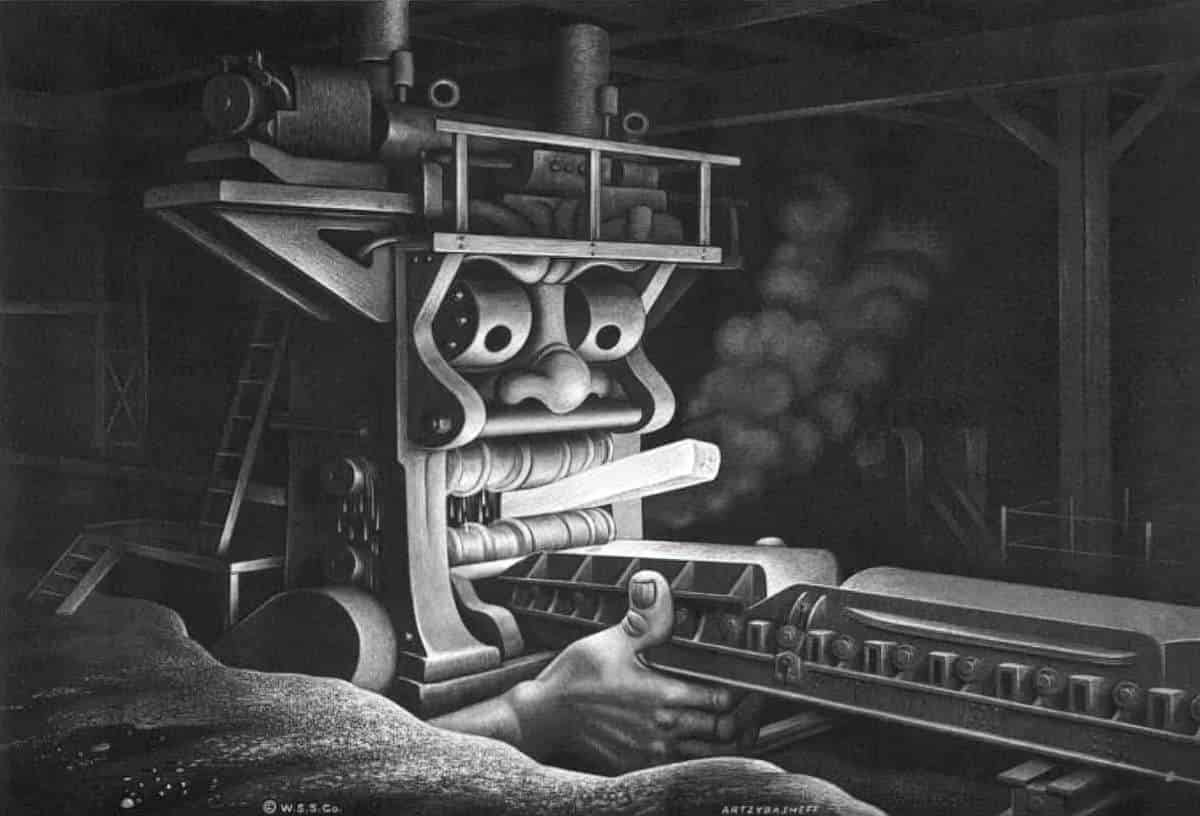

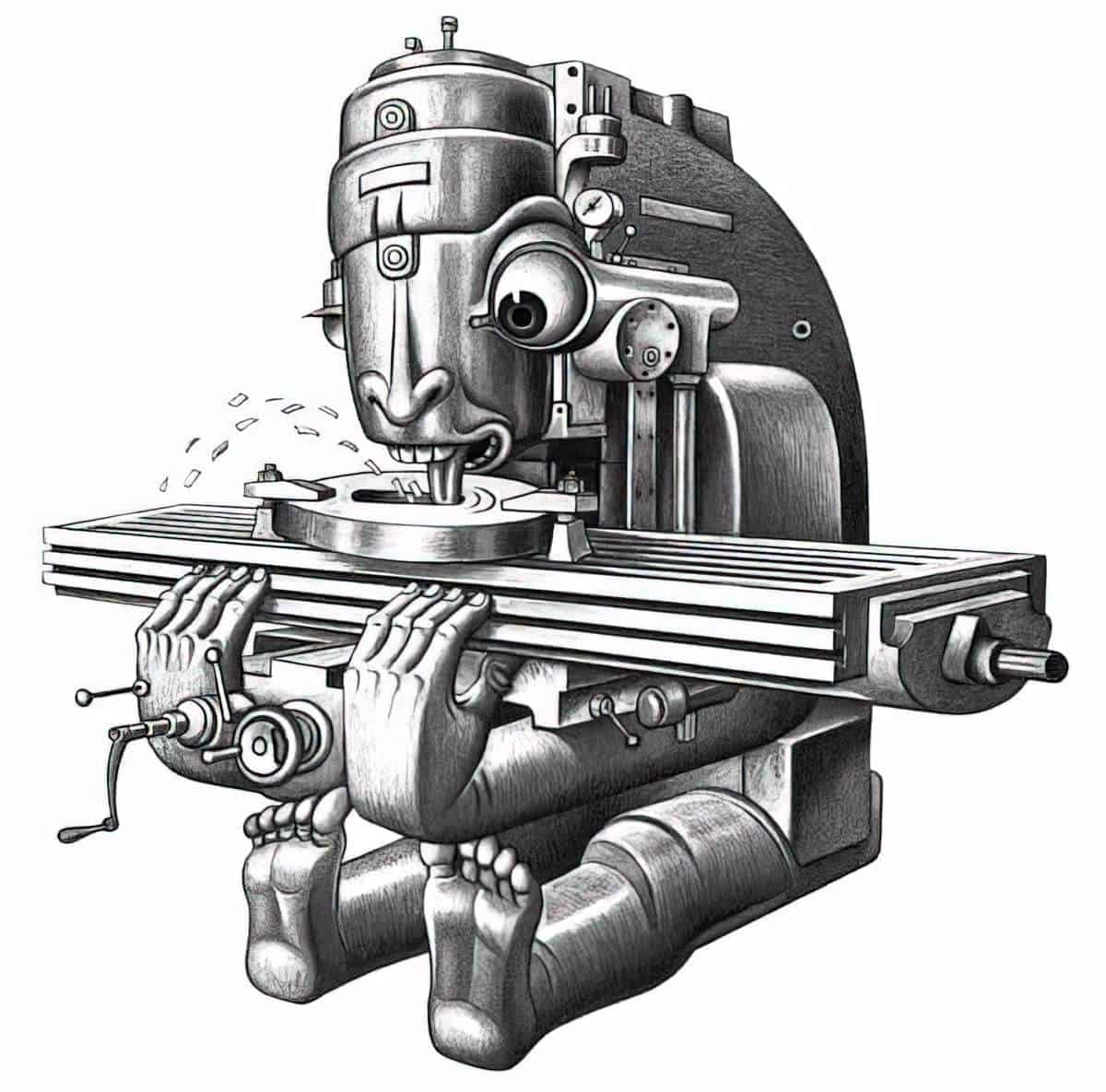

ART OF THE INDUSTRIAL ERA

SEE ALSO

Since the beginning of capitalist industrialization, humans have been mass-migrating from rural areas to cities. The post-apocalyptic story reverses this trend. This time, the cities become abandoned wastelands, not the regional towns. Reverse industrialization.

The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information

The history of how a deceptively ordinary piece of office furniture transformed our relationship with information The ubiquity of the filing cabinet in the twentieth-century office space, along with its noticeable absence of style, has obscured its transformative role in the histories of both information technology and work.

In The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (U Minnesota Press, 2021), Craig Robertson explores how the filing cabinet profoundly shaped the way that information and data have been sorted, stored, retrieved, and used. Invented in the 1890s, the filing cabinet was a result of the nineteenth-century faith in efficiency. Previously, paper records were arranged haphazardly: bound into books, stacked in piles, curled into slots, or impaled on spindles. The filing cabinet organized loose papers in tabbed folders that could be sorted alphanumerically, radically changing how people accessed, circulated, and structured information. Robertson’s unconventional history of the origins of the information age posits the filing cabinet as an information storage container, an “automatic memory” machine that contributed to a new type of information labor privileging manual dexterity over mental deliberation. Gendered assumptions about women’s nimble fingers helped to naturalize the changes that brought women into the workforce as low-level clerical workers. The filing cabinet emerges from this unexpected account as a sophisticated piece of information technology and a site of gendered labor that with its folders, files, and tabs continues to shape how we interact with information and data in today’s digital world.

interview at New Books Network

Header painting: John Wilson Carmichael – A View of Murton Colliery near Seaham, County Durham 1843 factory