I’m no Enid Blyton apologist when it comes to word echo and other matters of style, but Enid Blyton never wrote the phrase ‘lashings of ginger beer’. This phrase was used in a popular parody called Five Go Mad In Dorset, and is now often mistakenly attributed to the author herself.

Enid Blyton did use the word ‘lashings’, and there was a lot of ginger beer. I also remember lemonade, but what was it the children were actually drinking? Well, it wasn’t 7UP. The lemonade consumed by the Famous Five would have been sugar and lemon juice mixed in cold water, not the very high sugar carbonated variety. That’s simple enough to make. What about the ginger beer? Was it alcoholic? Were the children getting drunk, imagining those pixies, goblins and mushroom rings with lands at the tops of trees and chairs that grew wings?

In Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, the Swallows pretend that they’re drinking ‘grog’ instead of ginger beer. (This is all part of their pirate fantasy.)

To make traditionally brewed, homemade ginger beer, you will also need some lemons. Lemons plus ginger root and sugar and cream of tartar and brewer’s yeast. You can find a recipe for it here. The fizziness comes from the fermentation process, and required about four days to make — these are cooking skills which have been lost today. But our guts coevolved with the bacteria found in fermented foods and we should probably to go back to eating more of them to achieve well-balanced guts. That fermented stuff would not have been as sweet as today’s beverages by far, despite requiring quite a bit of sugar — that’s because bacteria eat the sugars in order to populate. (Hence, traditionally made sauerkraut is so sour — the bacteria has eaten any fructose out of it.)

There probably was a bit of alcohol in it if left for weeks, but if left for less than a week the alcohol is negligible. Basically, we don’t really know if Joe, Bessie and Fanny were getting pissed when they took a picnic into the woods, because we didn’t know how long it had been brewed for.

Edith Nesbit was also a fan of ginger beer. It makes me wince when Robert uses it to wash sand out of Lamb’s eyes, but remember it wasn’t the super fizzy stuff you’re probably thinking of:

The thoughtful Robert had brought one solid brown bottle of ginger-beer with him, relying on a thirst that had never yet failed him. This had to be uncorked hurriedly — it was the only wet thing within reach, and it was necessary to wash the sand out of the Lamb’s eyes somehow. Of course the ginger hurt horribly, and he howled more than ever. And, amid his anguish of kicking, the bottle was upset and the beautiful ginger-beer frothed out into the sand and was lost for ever.

Five Children and It

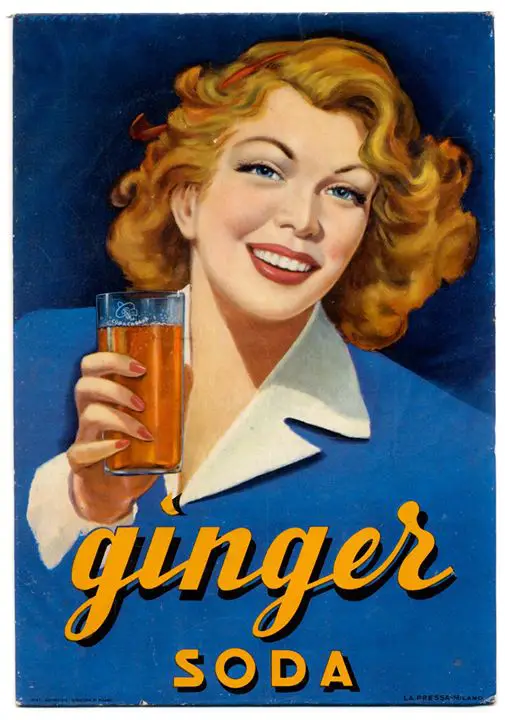

Australians were busy making their own ginger fizzy drinks, lest you think it was limited to the British Isles:

Food In The Work Of Enid Blyton

Blyton’s most prolific period of writing took place during the war era when food rationing meant that the majority of people in England were eating less than they had throughout the whole of the twentieth century. Following the outbreak of WW2, food rationing began in January 1940 and continued until 1954. The average weekly rations consisted of one shilling and sixpence worth of meat, eight ounces of sugar, four ounces of butter or fat, one egg, one ounce of cheese, with jam and honey also heavily rationed. Fresh vegetables were in short supply, unless grown in the home vegetable garden.

While the Famous Five were consuming fat red radishes, their readers were being fed banana sandwiches made with parsnips and banana essence or carrot tart glazed with lemon jelly to make a pudding, and while the Secret Seven breakfasted off well-buttered home-baked bread with chunky marmalade, their devotees never even saw fruit like oranges and bananas and had to make do with the infamous Woolton Pie, a combination of carrots, parsnips, turnips, and potatoes, covered with white sauce and pastry.

Barker

[…] Blyton can hardly be portraying the period realistically. […] the original appeal of Blyton’s food fantasies was intensified by the reader’s knowledge that their own family teatime was never likely to be as scrumptious as the feast Blyton served for them. And, for contemporary readers, the appeal lies in the huge quantities and the exoticism of the homemade foods in her narratives which, because of healthy-eating discourses and the lack of time generally available in contemporary households to produce such meals, are usually denied them. From this perspective it can be seen that a large proportion of the readers’ enjoyment is vicarious, a form of voyeurism, a chance to experience gluttony second-hand.

Carolyn Daniels, Voracious Children: Who Eats Whom In Children’s Literature

Enid Blyton and Froebel Training

Enid Blyton would have had all the skills of a good housekeeper, even if she preferred to write instead. As a student teacher Blyton received Froebel training, which encourages housekeeping, cooking, gardening and farming as a means of expression for young children.

Blyton’s ideal was one in which the earth-mother or a substitute earth mother provides food (preferably home-grown) for her cubs.

Barker

Mothers in Enid Blyton’s books tend to be plump, good at home-making and cheerful. While the children were out having their adventures, we can guess at what the mothers were doing: They were in the kitchen, fermenting fizzy beverages and making fruit cakes.