A key term in classical Chinese poetry is ju jue yi bujue (句絕意不絕) which means “lines that end but meaning that does not end.” This is a useful distinction, and a similar concept applies to many short stories.

Staying in Asia, Japan also has a concept which applies to many types of short story endings: Yugen (幽玄) refers to a concept which holds something back, keeping certain facets shrouded in mystery. Yugen stories have ambiguous endings, and also many other stories hidden between the lines.

I have encapsulated everything I know about story endings elsewhere. Almost all narrative ends with a Anagnorisis followed by a hint at the main character’s New Situation, though sometimes writers leave off the New Situation for the audience to extrapolate. The Wrestler is an excellent film example of Extrapolation.

In this regard, The Wrestler feels like a short story in tone. If you like to read short stories, you probably fall into the category of audience who enjoys piecing things together, imagining the outcome for yourself.

Another film which does this is Ghost World. In his review of Ghost World, Roger Ebert points to a trope more reminiscent of short stories than of film:

The movie sidesteps the happy ending Hollywood executives think lobotomized audiences need as an all-clear to leave the theater. Clowes and Zwigoff find an ending that is more poetic, more true to the tradition of the classic short story, in which a minor character finds closure that symbolizes the next step for everyone. “Ghost World” is smart enough to know that Enid and Seymour can’t solve their lives in a week or two. But their meeting has blasted them out of lethargy, and now movement is possible. Who says that isn’t a happy ending?

Roger Ebert

SHORT STORIES ARE ALL ABOUT THE ENDINGS

The short story is about form — less so than the poem, but more so than the novel. Endings should be fundamental. Their job is not so much resolution; a short-story ending wants to somehow emphasises or echo the quality of the story, as though a story’s voice, in its dying fall, can reminds us of everything we have just read. Even an airy, apparently open ending, like those in the stories of Lydia Davis or Alice Munro, is a way of saying ‘this is what my story is about’.

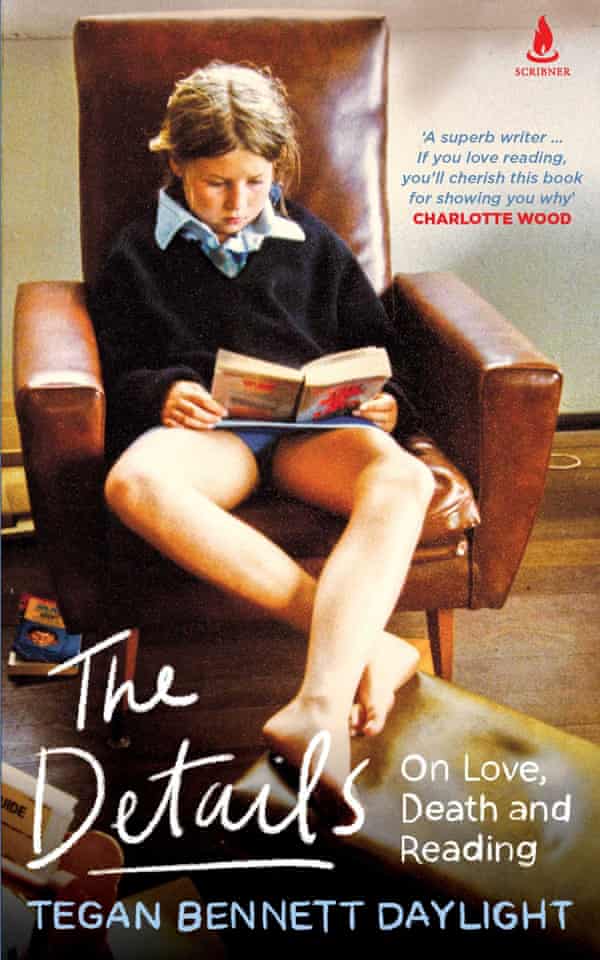

Tegan Bennett Daylight, The Details

A book about the connections we form with literature and each other

Tegan Bennett Daylight has led a life in books – as a writer, a teacher and a critic, but first and foremost as a reader.

In this deeply insightful and intimate work, Daylight describes how her reading has nourished her life, and how life has informed her reading. In both, she shows us that it’s the small points of connection – the details – that really matter: what we notice when someone close to us dies, when we give birth, when we make friends. In life’s disasters and delights, the details are what we can share and compare and carry with us.

Daylight writes with invigorating candour and compassion about her mother’s last days; her own experiences of childbearing and its aftermath (in her celebrated essay ‘Vagina’); her long admiration of Helen Garner and George Saunders; and her great loves and friendships. Each chapter is a revelation, and a celebration of how books offer not an escape from ‘real life’ but a richer engagement with the business of living.

Yep, there is such a thing as a ‘short story ending’ even if the story is not a short story. Even if it’s a film. We might instead call it a ‘lyrical’ ending.

“Get in, get out” is a maxim you’ll have heard before when it comes to writing short stories. In this post, I collect various interpretations on the “Get Out” part of that old chestnut. What does it mean, exactly, to Get Out?

The last collaborator is your audience…when the audience comes in, it changes the temperature of what you’ve written. Things that seem to work well — work in a sense of carry the story forward and be integral to the piece — suddenly become a little less relevant or a little less functional or a little overlong or a little overweight or a little whatever. And so you start reshaping from an audience.

Stephen Sondheim

Ambiguity is the mark of good literature, be it for children or adults.

Ursula Dubosarsky, SMH

The short story is about form — less so than the poem, but more so than the novel. Endings should be fundamental. Their job is not so much resolution; a short-story ending wants to somehow emphasise or echo the quality of the story, as though a story’s voice, in its dying fall, can remind us of everything we have just read. Even an airy, apparently open ending, like those in the stories of Lydia Davis or Alice Munro, is a way of saying ‘this is what my story is about’.

Tegan Bennett Daylight, The Details

As much as possible, the end of the story should lie open, so that you feel, that your people have got to go on living when the story is over.

V.S. Pritchett

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN NOVEL AND SHORT STORY ENDINGS

Using different terminology Nancy Kress is saying the same thing: The New Situation is often left off. She goes even further in fact, saying even the Anagnorisis can be left off, with a short story concluding right after the Battle (ie. climax).

The truth is that although everything in any work of fiction should contribute to the whole, the last few paragraphs of a novel are relatively unimportant. A novel is so long that by the time the reader comes to the end, 99 percent of the plot, character development, theme and everything else are over. And since the structure of a novel usually requires a climax followed by a denouement, the very end of a novel is a time of decreasing tension. Nothing startling, new or highly emotional is likely to turn up this late in such a lengthy tale. A short story is much different. The climax may be the ending. Even when an additional scene follows the climax, it is likely to carry heavy symbolic significance. And the shorter the story, the more important the last few paragraphs become.

In a certain kind of short story, the last sentence is especially crucial.

Nancy Kress, from Beginnings, Middles and Ends

PLOTTED VERSUS LITERARY

Kress does make a careful distinction between the ‘plotted short story’ and the ‘contemporary literary short story’. The plotted short story follows classic story structure (Shortcoming/Need/Problem, Desire, Opponent, Plan, Battle, Anagnorisis, New Situation). Stephen King and Jeffrey Archer write plotted short stories. They are enjoyed by a wider audience, who come to them via novels.

In a literary story, perhaps nothing is resolved. Readers unused to these stories often say, “Nothing happened,” or may think they’re missing the last page, or didn’t ‘get it’. Sometimes the point is that there is no resolution — because life can be like that. These stories are ‘the question minus the answer‘. Literary stories make their point via symbolism.

One thing about the short story is that it’s kind of an exotic, hothouse version of the “real” story. It does a little more—there’s more compression, of course, but also a higher expectation of shapeliness and some kind of aesthetic closure—a moment where the wires the writer has filled with current get a chance to really cross.

George Saunders

IT’S ALL ABOUT THE QUESTION, NOT THE ANSWER

Describing a short story by Amy Tan, the following is from J. T. Busnell, about the issues his students sometimes have when studying short stories which end abruptly:

And then comes the final line: “I closed my eyes and pondered my next move.” My students often complain that this ending seems abrupt, unfinished. In the anthology we use, it comes at the very bottom of the page, and students often admit to having flipped to the next page, expecting the story to continue. Usually I avoid telling them that it does continue in the collection of linked stories, because doing so allows students to dismiss the ending as a concession to the larger narrative or as something other than an ending. Instead, I direct them to the letter by Chekhov in which he famously instructs A.S. Suvorin, “You are right in demanding that an artist approach his work consciously, but you are confusing two concepts: the solution of a problem and the correct formulation of a problem. Only the second is required of the artist.” In other words, the writer’s job is, first, to write about questions complex enough that they avoid simplistic answers or easy moralizing and, second, to demonstrate such questions with precision and accuracy. The writer’s job is not, however, to answer them. Answers are not only reductive, they’re also political, prescriptive, moralistic, and this undermines the efforts of such realists to be “visible nowhere.”

This is exactly what Tan’s ending accomplishes. To show Waverly’s “next move” would provide an answer, and, as Chekhov says, that’s not her job.

Right, so if we’re writing a literary short story we’re onto a winner if we are able to articulate a good question.

A COMMON PROBLEM WITH SHORT STORY ENDINGS

Here’s what it doesn’t mean: Chopping off the last two stages of the seven step structure. At The Masters Review, editors have seen this in their submissions. They are well placed to describe literary endings done badly:

We regularly reject stories where we feel the endings aren’t fully earned. I can best summarize this to mean, that for me, when I read a story where I feel the writer is working toward an end but the rest of the piece isn’t supporting that conclusion, whether it be emotionally, on a plot level, or thematically, that ending isn’t fully earned. […]

A story’s ending is most powerful when it feels like the culmination of everything that has been bubbling throughout it — the character’s motivations and actions, the preoccupations of the prose. I know that, in the past, incredibly strong stories that end with a seemingly random disaster have been hotly debated. We get upset when we come to the end of a carefully crafted story and a character who we’re invested in suddenly dies, or is injured, or it turns out (please, no!) has been dreaming this whole time — with no clear reason, we’re often left wondering what the author’s intention was. For example, one of our honorable mentions (which, overall, we really enjoyed) for this last contest ends with a shot being fired (though it’s not clear that any harm is done by it), and neither one of us was sure why. Though this sort of violence is built to more thoroughly in this story than others, here it seemed to take the place of a deeper reflection or significance.

Of course, there are degrees to this. I think that story endings can often be strengthened. One of the most common edits I make to pieces we do accept is to change the ending. Take, for example, “Family, Family,” our second-place Fall Fiction Contest winner. (Read it now to prevent any spoilers.) Though the original ending felt natural enough, all of our editors thought that it was lacking power and that it could have had a clearer “takeaway,” so I flat-out asked the author what she meant by it. Her answer was clear: she wanted to convey the desire of a first-grader who has been ridiculed by his peers to return to the safety of his nursery school classroom, to go backwards in time rather than face the challenges of growing up. We ended up changing the ending image entirely, so that the little boy literally climbs into a pine doll cradle, for which he is (of course) too big. This resonates instantly.

Even when editing pieces with quite a bit of narrative distance … I’ll often push the author to give a little more (even a sentence!) at the end. I never want the ending of a story to be too “neat,” but at the same time I want to finish it feeling satiated.

The Masters Review

PH.S.: Is not there a danger, many people would say, of the short story becoming artificial with such components as the final twist, or the introduction of short bits of information at any point of the story that will serve to bring about the conclusion, or the necessary selection of components in which the role of the writer is too obvious? Do you think there is some truth in all that, that there is a danger for the short story?

V.S.P.: Well there’s the same sort of danger really that there is in the novel on a larger scale. I think if you try to write short stories well, you try and evade those things. I mean they stick out a mile when you read them through to you. And you think “No, that is really not so, not like the life I’m trying to put in.“ Nevertheless, there are a vast number of anecdotal stories which are like that. I think actually there is a public taste for the anecdote, that is much stronger than it is for the story which is not an anecdote. Maupassant, Maugham, even Chekhov sometimes, sinned in this way. One must of course distinguish between the “trick“ ending and the “closed“ ending in which the story has a fitting end. I think we’ve had far too many anecdotal stories. The twist can be avoided entirely by making it spring from the characters themselves.

V.S. Pritchett

This advice is echoed by David Jauss, who wrote a book called On Writing Fiction. In his chapter called Some Epiphanies About Epiphanies, Jauss writes:

there are indeed far too many epiphanies in American fiction these days, and […] most of them are unearned or unconvincing, the literary equivalent of faked orgasms.

David Jauss

Jauss thinks most of the problem with epiphanies is that they happen at the end of the story. He offers examples of stories which do not put the epiphany at the end of the story, but play with expected structure by placing it elsewhere.

I’ve noticed myself that short story writers can play with placement of the epiphany by first giving the reader their epiphany, and holding onto the character’s epiphany until after they’re done. (The sex metaphors keep on coming.) Examples of authors who play around with the placement of the epiphany (or anagnorisis):

- Charles Baxter

- Sheila Schwartz

- Alice Munro

- John Updike

Oftentimes, and we have to remember this, the character experiences an epiphany OFF THE PAGE (or screen), and we only know they’ve had one because of the plans they make next.

THE INFLUENCE OF CHEKHOV

A word for the literary short story which leaves the reader to extrapolate is Post-Chekhovian, because Anton Chekhov is kind of famous for starting this trend. James Joyce also wrote like this, ending with ‘tacit’ epiphanies rather than clear anagnorises.

DRAMATIC VS AESTHETIC CLOSURE

Whereas Nancy Kress makes a distinction between ‘plotted’ and ‘literary’, critic Charles May draws a distinction between stories resolved dramatically and stories resolved aesthetically. I think this is a different way of saying the same thing.

A primary characteristic of the modern post-Chekhovian short story is that stories that depend on the metaphoric meaning of events and objects can only achieve closure aesthetically rather than phenomenologically. James Joyce’s stories often end with tacit epiphanies, for example, in which a spinster understands but cannot explain the significance of clay or in which a young boy understands but cannot explain the significance of Araby. His most respected short fiction, “The Dead”, is like a textbook case of a story that transforms hard matter into metaphor and that is resolved only aesthetically. Throughout the story the “stuff” described stubbornly remains mere metonymic details; even the snow that is introduced casually into the story on the shoes of the party-goers’ feet is merely the cold white stuff that covers the ground — that is until the end of the story when Gabriel’s recognition transforms it into a metaphor that closes the work by mystically covering over everything.

Charles E. May, The Art of Brevity: Excursions in short story theory and analysis

May goes on to explain that Bernard Malamud is one of the best-known writers within this tradition of stories that end with aesthetic rather than dramatic resolutions. He seems to construct his stories backwards. The meaning of his stories is left to the reader. Irreconcilable forces are resolved aesthetically.

The short story, standing alone, with no life before it or after it, can receive no … comforting merging of the extraordinary with the ordinary [like the novel can]. For example, we might hypothesise that after Miss Brill has been so emphatically made aware of her role in the park each Sunday, she will still go on with her life, but Katherine Mansfield’s story titled “Miss Brill” gives us no such comforting afterthought based on our confidence that “life goes on”, for it ends with the revelation.

Charles E. May, The Art of Brevity: Excursions in short story theory and analysis

SECRET CHARACTER KNOWLEDGE

On Twitter, author Adam O’Fallon Price uses the phrase ‘secret character knowledge’ to describe a difference between good and great short stories:

Most great short stories contain a secret knowledge, usually about the narrator or protagonist, that the reader senses as they read. The story understands some deep truth about the main character that is largely unavailable to them, but that hovers on the periphery. Very often, this knowledge is at last articulated in the end, either ambiguously or explicitly. Great endings are often, but not always, an expression of the story’s secret knowledge—this is why they are so satisfying. I’ve heard it said that great story endings feel both surprising and inevitable. They’re surprising because they articulate a deep knowledge left unsaid; they’re inevitable for the same reason. The reader has sensed a thing held in reserve.

Adam O’Fallon Price

He gives the example of Denis Johnson’s “Emergency” then says:

Anyway, this kind of hidden character knowledge represents the dividing line between good and great fiction imo. Good literary fiction might give the reader coherent dramatic narrative + satisfying arcs rendered in quality prose. But it is flat, nothing lurking in the depths. Great short fiction has the feeling of a secret being shared. It isn’t just or even primarily what happens, it’s what’s being held in reserve, the words not fully spoken until the very end, if then.

Adam O’Fallon Price

(When secret knowledge is only ever aesthetically implied, is this a form of literary Mystery Boxing?)

TAXONOMIES OF SHORT STORY ENDINGS

Ah, my favourite. Taxonomies. Pick your fave and go with it.

GERLACH

All short stories use at least one of five signals of closure: solution of the central problem, natural termination, completion of antithesis, manifestation of a moral, and encapsulation.

John Gerlach, Toward the End: Closure and Structure in the American Short Story, 1955

Gerlach’s study is about how the anticipation of the ending of a short story structures the whole:

- SOLUTION OF THE CENTRAL PROBLEM: This kind of ending is more common to the short story than to novels. Short stories focus on one problem only. The short story is over when that one problem is solved.

- NATURAL TERMINATION: “is the completion of an action that has a predictable end.” For example, the day ends, the main character dies. A lot of picture books have this kind of ending too, with the beginning of the story coinciding with the main character getting out of bed, and ending when the main character is tucked in at night. Other types of natural terminations are, for instance, a visit being over (because there’s an implied return to point of origin), or a mental state like happiness or bliss suggests the end of some process.

- COMPLETION OF ANTITHESIS: Antithesis refers to any opposition, often characterised by irony, that indicates something has polarised into extremes. In short stories, space is often metaphorical. There’s an emphasis on mental life. When a character sets out on an adventure, that character is actually exploring a set of attitudes towards something. When a story returns to any aspect of the beginning, this is one form of ‘antithesis’. The new territory doesn’t have to be explored because boundaries have been established by the story.

- MANIFESTATION OF A MORAL: The reader’s sense that a theme has emerged can give a story a sense of closure.

- ENCAPSULATION: “a coda that distances the reader from the story by altering the point of view or summarising the passing of time.”

WINTHER

But in The Art of Brevity: Excursions in short story theory and analysis, Per Winther is keen to point out that this is not an exhaustive list.

Winther’s alternative taxonomy of short story endings:

- SOLUTION OF THE CENTRAL PROBLEM

- NATURAL TERMINATION

- EMOTIONAL AND/OR COGNITIVE MATERIAL

- CIRCULARITY

- MANIFESTATION OF A MORAL

- EVALUATION

- PERSPECTIVAL SHIFT

EVALUATION

Winther renames Gerlach’s last category of Encapsulation EVALUATION. Examples of evaluations as closures:

- I was glad I was not there.

- I had never met such a bore in my life.

An evaluation as closural marker is often the first-person narrator’s exasperated final comment.

Evaluations often serve as the manifestation of a moral, also.

- “I guess he loved the man as much as I did the horse because he knew what I knew.”

MORE ON WINTHER’S ‘PERSPECTIVAL SHIFT’

Modern short stories tend to have a more gradual shift of narrative focus at the story’s end. In these cases there is no change in point of view — the focalizer stays the same, and time is not an essential factor. Still, a notable change of perspective marks that the narrative may now come to a halt. Hence the addition of Winther’s seventh category.

METONYMIC VS METAPHORIC

Charles May thinks in terms of metonymic vs metaphoric. This is where my head starts to hurt.

- Metaphor substitutes a concept with another; metonymy selects a related term.

- Metaphor is based on similarity; metonymy is based on contiguity.

- Metaphor suppresses an idea; metonymy combines ideas.

Why is the short story’s resolution often metaphoric? Since the short story cannot reconcile “the tension between the necessity of the everyday metonymic world and the sacred metaphoric world,” [Charles] May finds that “the only resolution possible is an aesthetic one.”…the short story’s brevity “force[s] it to focus not on the whole of experience … but rather on a single experience lifted out of the everyday flow of human actuality.”

Charles E. May, The Art of Brevity: Excursions in short story theory and analysis

THE STRANGE TIME-WARPY LOOPINESS OF SHORT STORY ENDINGS

In a short story, an end does more than complete a pattern and effect closure. The amazing thing about the short story is that beginning and end make a strange loop: beginning is end, and end is also beginning. Epiphany expressed through analogy fuses past, present, and future in a moment of continuous flux. Epiphany encompasses answers to the questions posited by structure, reconciling the contraries inherent in the differences between appearance and reality, on the one hand, and form and content on the other.

Mary Rohrberger, The Art Of Brevity

In other words, a common plot shape for a short story is the circle, if only metaphorically.

Open Endings

Storytellers have thought of many ways to create a circular feeling of completion or closure, basically by addressing the dramatic questions raised in Act One. However once in awhile a few loose ends are desirable. Some storytellers prefer an open-ended Return. In the open-ended point of view, the story-telling goes on after the story is over; it continues in the minds and hearts of the audience, in the conversations and even arguments people have in coffee shops after seeing a movie or reading a book.

Writers of the open-ended persuasion prefer to leave moral conclusions for the reader or viewer. Some questions have no answers, some have many. Some stories end, not by answering questions or solving riddles but by posing new questions that resonate in the audience long after the story is over.

Hollywood films are often criticized for pat, fairy tale endings in which all problems are solved and the cultural assumptions of the audience are left undisturbed. By contrast the open-ended approach views the world as an ambiguous, imperfect place. For more sophisticated stories with hard or realistic edges, the open-ended form may be more appropriate.

from The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler

Michael Connelly On Tidy Endings

In an interview at The Bestseller Experiment podcast, bestselling crime writer Michael Connelly says that he doesn’t tidy everything up in his novels. Connelly has a background as a crime journalist, and in his real world earlier career many, many crimes were never tidied up. When he left to become a full time novelist he left many files open-ended. This was a reminder to him that real life is vastly different from fiction. He tidies his book endings up a lot more than is done in real life, but refuses to tidy absolutely everything.

A Brief History Of Open Endings

A number of significant changes took place as a result of the Industrial Revolution in the way we tell stories – endings are just as likely now to consist of an ‘open ending’, partly to add an air of uncertainty and partly because in a godless universe death doesn’t mean what it once did. As Shakespearean scholar Jan Kott noted before him, ‘Ancient Tragedy is loss of life, modern Tragedy is loss of purpose’. Characters nowadays are just as likely to drift into meaningless oblivion as to die.

Into The Woods by John Yorke

AUTHORS ON WRITING ENDINGS

I often have an idea of what the outcome may be, but I have never demanded of a set of characters that they do things my way. On the contrary, I want them to do things their way. In some instances, the outcome is what I visualized. In most, however, it’s something I never expected. For a suspense novelist, this is a great thing. I am, after all, not just the novel’s creator but its first reader. And if I’m not able to guess with any accuracy how the damned thing is going to turn out, even with my inside knowledge of coming events, I can be pretty sure of keeping the reader in a state of page-turning anxiety. And why worry about the ending anyway? Why be such a control freak? Sooner or later every story comes out somewhere.

Stephen King, from On Writing

If you choose to use a protagonist who is an admirable crook, do not fall into the moralistic trap of using the cliché ending in which, after all his trials and tribulations, the lead loses the stolen loot either through a quirk of fate, the machinations of an even morecrooked partner, or the cunning of the police. If you have established your crook as a sympathetic character and have gotten your reader to root for him throughout the bank robbery (or whatever), your audience will only be frustrated when he loses everything simply because you feel that you must prove “crime doesn’t pay.”

Dean Koontz, from Writing Popular Fiction

I can’t start writing until I have a closing line.

Joseph Heller

I rewrote the ending of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times before I was satisfied.

Ernest Hemingway

Stories do not end.

ANAÏS NIN

RELATED RESOURCES

- The Three Endings Of Alice Munro’s Story “Corrie” from Reading The Short Story Blog

- Ending A Short Story: Some Thoughts from Literary Lab

I don’t have a solution. Just concerning thoughts.

Ana Rodrigues