“Encounter” is a 1971 short story by New Zealand author Noel Hilliard (1929-1996).

Find it in New Zealand’s famous 20th century literary magazine Landfall, which is now available online.

LANDFALL, VOLUME TWENTY-FIVE, NO. 3, 1971 p. 270

NOEL HILLIARD’S WRITING STYLE

As you read “Encounter”, consider if you agree with the following assessment of Hilliard’s style, and whether it applies to this short story in particular:

[Hilliard’s] fame as an exponent of modern Māori life, based on his novels, has perhaps tended to obscure the fact that even in those a series of vignettes offers a broad picture of Pākehā life as well.

Hilliard tends towards the conservative. His narrative is finely controlled, but it is often pre-Mansfield in its concentration on telling rather than revealing.

Hilliard’s greatest weakness is his tendency to explicit moralising, which interrupts the narrative flow and causes the reader’s suspension of disbelief to crumble.

Nelson Wattie, translator (from German, French, Italian and Dutch to English), editor, lecturer, actor, radio scriptwriter, reviewer and professional singer. Wattie considers “Friday Nights are Best” Hilliard’s best short story.

AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND LANGUAGE

“An eight, please.”

In 1970s New Zealand, ordering “An eight” at a pub typically meant asking for a half-pint of beer. Aa traditional British pint is divided into eight fluid ounces. New Zealand has long since switched to metric.

h*ri

A highly offensive word for a Māori person.

Pākehā

A white New Zealander of European descent

pipi

A pipi is a type of shellfish found in New Zealand and Australia. The scientific name is “Paphies australis.” Pipis are bivalve mollusks, which means they have a hinged shell that consists of two parts. They are commonly found in intertidal zones, buried in the sandy or muddy seabed, and are known for their sweet and tender meat.

Pipis are a popular seafood in New Zealand and are used in various culinary dishes, such as pipi fritters, soups, and stir-fries. They are often harvested for both commercial and recreational purposes. Pipis are typically collected by digging in the sand or mud where they are buried, and this activity is often referred to as “pipi-picking.”

pā

A Māori “pā” (often spelled “pa” in English) is a fortified village or settlement that was historically built and used by the Māori people, who are the Indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand. Pā were a central aspect of Māori culture and society, serving as both defensive and residential structures.

Key characteristics of a Māori pā included:

- Defensive Structures: Pā were often situated on elevated terrain, such as hills or cliffs, to make them more defensible. They typically featured a series of trenches and palisades (fencing or walls made of wooden stakes) for protection. These defensive features helped safeguard the inhabitants from tribal conflicts and potential invasions.

- Terraced Gardens: Māori pā commonly included terraced gardens for the cultivation of crops like kumara (sweet potato) and taro. These gardens were a vital source of food for the community.

- Whare: Within the pā, there were houses or structures called “whare” where families or groups of people lived. Whare were typically made from natural materials like wood, flax, and thatch.

- Community Spaces: Pā often had communal meeting areas, known as “marae,” where important gatherings, ceremonies, and cultural activities took place.

- Storage Facilities: Storage pits were used to preserve food, such as kumara, for times when resources were scarce.

Today, while many traditional pā have been abandoned or lie in ruins, some are preserved and used as cultural and historical landmarks, allowing visitors to learn about Māori history and culture. Māori culture remains an important part of New Zealand’s identity, and pā continue to be of cultural and historical significance.

marae

A marae is a traditional Māori meeting ground or complex in New Zealand. The term “marae” refers not only to the physical space but also to the communal, spiritual, and social aspects of Māori life associated with it.

Key features:

- Wharenui (Meeting House): The wharenui is the central building on the marae and is traditionally a carved and adorned structure. It serves as a focal point for meetings, ceremonies, and other cultural activities. The wharenui typically features intricate carvings and serves as a place for welcoming guests and hosting events.

- Wharekai (Dining Hall): The wharekai is the dining hall or kitchen where communal meals and feasts are prepared and shared during gatherings.

- Whare Karakia (Prayer House): Some marae have a separate building for religious or spiritual activities, which is known as the whare karakia.

- Ātea (Open Space): The ātea is an open courtyard area in front of the wharenui, where various cultural performances and ceremonies take place.

- Urupā (Burial Ground): Some marae complexes include a burial ground or cemetery for ancestral burials.

Marae serve a variety of functions: welcoming visitors, conducting traditional ceremonies, celebrating important life events, discussing communal matters. They are also places where Māori cultural practices, such as haka (war dances) and waiata (songs), are performed.

rangatira

A “rangatira” is a person of high rank e.g. a ‘chief’. The word “rangatira” carries a sense of leadership, authority, and prestige within the Māori community. Rangatira are individuals who hold positions of significance and influence, often in both social and political contexts.

Tatau ka haere!

This phrase signifies the commencement of an event, meeting, or some form of collective action, with an emphasis on unity and cooperation.

E koe

“E koe” means “you”, used when addressing someone directly. “Hey, you!” (“I nga!” doesn’t seem to have a clear meaning in this context, but it may be used as an exclamation or expression of surprise or emphasis.)

to put someone’s weights up

To secretly disadvantage someone in some way. In this context, Paul is asking how Jason Pine can be so sure he won’t use his white man privilege to get him thrown back in the slammer, because surely the guy’s still being monitored for good behaviour.

SETTING OF “ENCOUNTER”

PERIOD

1970s, two nights before Christmas.

Christmas is symbolic in this story of colonisation. Europeans brought Christianity to New Zealand. Also, Christmas is meant to be a happy, festive time and this pub is no such thing. The beer is disgusting, there are flies, it’s raining and dreary outside.

DURATION

Paul spends about as much time in that pub as it takes us to read the story. (The word for this is ‘isochronical‘.) In isochronical stories, we feel we’re right there with the main character.

LOCATION

New Zealand, in a North Island country town

ARENA

a dive bar

MANMADE SPACES

Noel Hilliard writes a description of the unfamiliar pub as lonely. Literature students might call this ‘a liminal space‘:

It was more than lonely: you were known where you came from and you were known (if you were lucky) where you were going to; but here in the place between you were nobody, you didn’t exist, you just occupied space and made noises and jingled coins but you were totally without personality or presence and you began to wonder, after a while, who the hell you were and what you were supposed to be doing.

“Encounter”

This reflects the experience of being a white man in 1970s New Zealand. The Pākehā culture is specific to Aotearoa New Zealand, and very new in the scheme of human history.

WEATHER

Since it’s Christmas time in New Zealand, remember that means it is summer. However, the Christmas/New Year period is a notoriously unsettled time for New Zealanders, who frequently have their Christmas plans ruined by rain, wind and so on.

The morning had been overcast, mist had come down in the afternoon and showers in the evening and now Paul felt cold and damp and his feet were wet from puddles he hadn’t been able to see in the shadow of the railway station when he’d got off the train.

“Encounter”

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

There may or may not be some technology which your plot will rely on. In some genres (especially science fiction) this technology will be central.

Note that by the 1970s, passenger trains in New Zealand had gone the way of the moa. Contrast this to Janet Frame’s first short story collection, in which train travel between towns is the norm.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

“Encounter” takes Māori and Pākehā and pits them as opposition who must somehow find a way to rub along together, all travelling in the same ‘bus’.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “ENCOUNTER”

SHORTCOMING

“You wondered who you were and what you were supposed to be doing.” As the Pākehā Paul stands at the bar — the Every White Man — he wonders what he’s doing there in this nowhere space. This encapsulates the feeling of disconnection of a white man in New Zealand, who has no connection to The Mother Country (“Home”, meaning England), nor any particular connection to the land of Aotearoa. He’s trying to find his way.

DESIRE

On the surface level of the story, Paul Bennett is headed back to his home town for Christmas. It’s likely he works in the big smoke of Auckland. He has stopped at a small, unfamiliar town to catch a connecting bus to get back to see his father. For reasons we aren’t told, he hasn’t been home since ‘the war’. (Another minor war is about to break out in the pub.)

As his new “pub mates” point out, Paul is happy to blithely get on with his Pākehā life, without giving much thought to the fact that he is a settler living on unceded Māori land. Sure, there’s a pā in his home town. But he disrespects it by calling it The Pā. He doesn’t honour it by calling it by its individuating Māori name.

THE INVISIBLE KNAPSACK

Noel Hilliard several times mentions Paul’s suitcase, so let’s take a closer look. That suitcase must be symbolic. Funnily enough, a very similar metaphor was popularized by Peggy McIntosh in her 1988 essay titled “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” The concept is a metaphorical way of explaining how certain privileges are often unseen or unnoticed by those who possess them, much like items in a backpack that one carries without thinking about their weight or impact.

The invisible backpack represents the unearned advantages and benefits that individuals from a dominant or privileged group (in this case, white people) often experience in society without being consciously aware of them. McIntosh’s work primarily focuses on white privilege, but the concept can be extended to other forms of privilege as well.

Some examples of the privileges that may be included in this “backpack” are:

- Not being racially profiled or harassed by law enforcement.

- Having one’s culture and history widely represented and acknowledged in educational curricula and mainstream media.

- Not being subjected to negative stereotypes or microaggressions based on one’s race.

- Easier access to housing, employment, and educational opportunities.

- Being able to move through the world without fear of discrimination or violence based on one’s race.

- Being allowed to use your native language in public spaces such as school.

Imagine Paul carries white privilege in his suitcase. It’s with him all the time, everywhere he goes. He takes it for granted.

OPPONENT

The opponents in this story are pretty clear, but importantly, the two sides stand for entire cultural groups.

PLAN

The Māori men are out for some trouble tonight, and Paul makes a great target. First they check if he can speak Te Reo by asking him his name. These guys seem to have noticed Paul from a distance and struck a bet between themselves. When Paul says ‘the pa’, the guy called Jason is required to buy the drinks in.

Paul is on his own, outnumbered. He makes a good volley board for years of pent-up frustration against white colonisers. Alongside Hilliard’s readers, the Māori men consider Paul the Every White Man.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Noel Hilliard’s white man can’t say anything right. He doesn’t respect the landmarks, he seems to mock them by using English stereotypically associated with Māori. In the biggest insult, he uses the word ‘Chief’.

Whereas Paul is oblivious to his privilege, the Māori opponent is petty and easily offended, bordering on paranoid.

- Paul has a point when he says ‘the pa’ is the only one at the end of the line, so why specify? In all languages, speakers use the most economic method of communication by default.

- When he slips up and addresses Jason as ‘chief’, this is a common way of addressing someone without using his name, similar to how the Māori men addressed Paul as ‘boss’ when they first entered.

- When Paul says ‘youse’, this is likely an example of linguistic accommodation — Paul is trying to appease.

The character Jason Pine is so paranoid he puts me in mind of someone who’s been smoking pot all day and now he’s on the comedown. However, the accumulation of gaffes is significant here. If it were just one little microaggression, perhaps Jason could walk past. But it’s constant. This guy called Jason, even if he is paranoid, serves to point out to white readers what microaggressions like like and how frequent they come at you if you’re Māori. (This story was written before the word microaggression existed.)

Hilliard also avoids a cut-and-dry “Māori good, white man bad” story by telling us that Jason has been in prison for rape, a violent crime that any right-minded person would find shocking. Hilliard complicates the story further with the further information that Jason is quite possibly innocent of this crime, and was unjustly vilified due to his being Māori. Both scenarios seem equally plausible to readers of this story.

ANAGNORISIS

The unexpected possible reveal: The “Nice and Good Māori” is possibly the bad one, whereas the guy with the chip on his shoulder has the most upright morals and the most caring nature.

This story throws a question rather than provides an answer: What does it mean to be a “Good Māori”? A “Good Coloniser”? Like the bus driver Mattie, Paul just walks around minding his own business without stepping in when he sees wrong. He leaves that to someone else, someone who garners the reputation for ‘having a chip on his shoulder’. (‘Feminist killjoys’ will relate.)

The standard we walk past is the standard we accept. Paul accepts the views of the coloniser without challenging them, so can he really say he’s on Jason’s ‘side’?

NEW SITUATION

After getting a clip from Jason, he gets on the bus and continues on his way.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

When Paul gets to his destination he’ll be passing that pa and he won’t look at it in the same way ever again. And he won’t put Jason’s ‘weights up’ for knocking him to the ground because he knows the picture of violence is far bigger than anything that happened to him that night.

RESONANCE

The ideas in “Encounter” are much better understood today, in general. Lately in AoNZ there’s a brouhaha over Māori language signage. Racism hangs around like a pall over the country.

I would say that far more white New Zealanders are aware of the significance of the Marae and the Pa, know significantly more Māori language than typical 1970s Pākehā did, and if they don’t fully understand the concept of privilege, they’ve at least heard the term ‘white privilege’ and have a theoretical knowledge of what it means.

This wasn’t the case last century.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR NOEL HILLIARD

Noel Harvey Hilliard was born in Napier in 1929. As an adult he lived in Wellington – Te Whanganui-a-Tara and worked as a primary school teacher. His major work started to appear in the 1960s. He is best remembered for his novel Māori Girl.

I don’t know if Noel himself was of Māori descent, but he attended a Māori school as a boy in Hawkes Bay. His wife Kiriwai Mete was of Ngāti Kahu and Ngāpuhi descent. They married in 1954. Together they had two boys and two girls. Kiriwai died in 1990. His famous novel was based partly on his wife’s experiences.

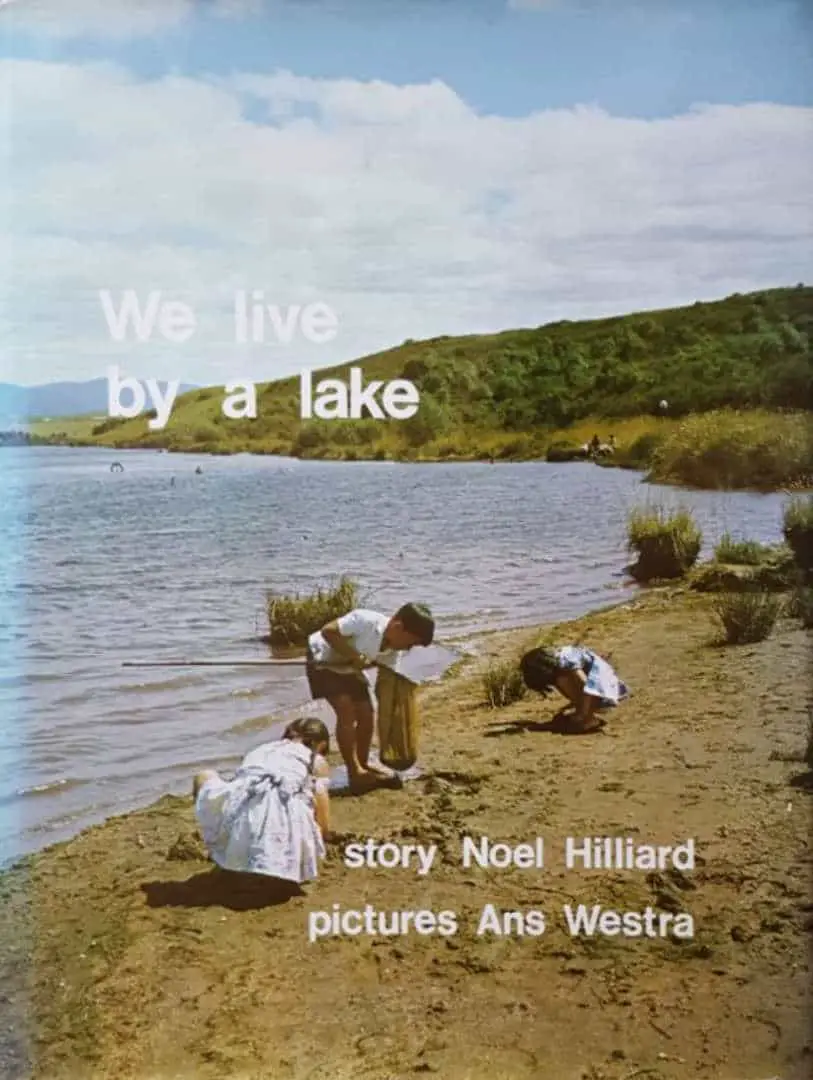

In 1972 Noel Hilliard and Dutch-born New Zealand documentary photographer Ans Westra published a children’s picture book called We Live by a Lake. As a child of the 80s, the cover of this book feels super nostalgic. I must have seen books with this exact font and basic graphic design all through my childhood.

Once in high school English we studied a Noel Hilliard short story called “Erua”, which left a lasting impression on me. A young Māori boy idolises his male school teacher because the teacher is the only man in his life who feels safe. But one night he encounters his beloved school teacher drunk, stumbling out of the pub and his world is shattered.

When I went through New Zealand’s school system at the end of the 20th century, Noel Hilliard’s work was fairly commonly taught by his fellow teachers. (The teaching world in NZ has always been a small one.)

Our Year 11 task was to rewrite the ending, because our teacher didn’t think it was finished. I hated this activity — rewriting the ending was wholly unnecessary! I suspect, in hindsight, our English teacher preferred Noel Hilliard’s usual style of writing, which these days looks a bit moralistic.

Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to find a copy of Noel Hilliard’s Selected Stories, in which “Erua” appears. Nor is there any copy of the story online, unlike the works which appeared in New Zealand’s famous literary magazine Landfall, now digitally archived. If anyone has a digital copy of “Erua” by Noel Hilliard, please let me know! I imagine a class set of copies still float around some of AoNZ’s high school English departments.

Noel Hilliard died in 1996, just a few years after my cohort of students read some of his short stories in high school English. (Ans Westra died in 2023.) I’m not sure how frequently his work is taught today. I suspect he’s one of those authors whose name and work is in danger of being entirely forgotten.