Storytellers can manage audience emotions by writing characters who do — and feel — the unexpected. In doing so, writers can subvert common emotional tropes to great effect.

Why is this technique necessary and so effective? A major element of good storytelling is surprise.

The writer’s characters must stand before us with a wonderful clarity, such continuous clarity that nothing they do strikes us as improbable behavior for just that character, even when the character’s action is, as sometimes happens, something that came as a surprise to the writer himself. We must understand, and the writer before us must understand, more than we know about the character; otherwise neither the writer nor the reader after him could feel confident of the character’s behavior when the character acts freely.

John Gardner, The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers

And why is it so important that writers avoid the cliched and expected when writing emotional responses?

Reading about the response of people in stories, plays, poems, helps us to respond more courageously and openly at our own moments of turning.

Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art

Today’s first storytelling example comes from music.

Canadian singer songwriter Michelle Gurevich is expert at creating songs which function as antidotes to pop messages. Her songs have titles like Drugs Saved My Life, standing in contrast to more conservative ideologies such as The Drugs Don’t Work from The Verve.

Drugs do save lots of lives — generally they’re on prescription, though. There remains a stigma regarding certain classes of drugs: antidepressants and stimulant medications cop it pretty bad.

No surprise, then, that The Verve’s The Drugs Don’t Work is pop whereas you may never heard of Drugs Saved My Life, unless you’re reading this from Eastern Europe where Gurevich is popular — an interesting cultural difference.

When drugs ruin someone’s life, the emotions around that narrative are intense; when drugs save someone’s life, bringing the character back to equilibrium, this prioritises the muted story over the sensational one. But expressing a muted response is one good way to subvert a dominant narrative: That drugs dependence is bad.

Similarly, Michelle Gurevich’s I Saw The Spark feels like the literary counterpoint to Dolly Parton’s pop song Jolene.

In Jolene, the singer/narrator contacts the rival woman and pleads.

The lyrics of Jolene appeal to baser instincts — calling is what we might do if our frontal lobes weren’t doing their job.

MY MAN: (comes home)

ME: (nervous) how was the store

MY MAN: fine

ME: oh thank g —

MY MAN: ran into jolene

ME: oh no

MY MAN: she mentioned you left kind of an intense voicemail— Rob Dubbin (@robdubbin) July 28, 2019

Jolene as a song is therefore cathartic, and although I really do think the singer/narrator should ditch the man, those feelings of jealousy and inadequacy are real, relatable and… intense.

Gurevich’s song I Saw The Spark evokes a different emotion in a similar situation and therefore makes an excellent counterpoint to Jolene. The singer/narrator demonstrates unexpected emotional maturity when her partner is attracted by another woman. She acknowledges that sometimes in love you win, other times it’s your turn to lose. This is a fatalistic but realistic worldview. Finally:

And there’s nothing I can do

But to love you both the more

No there’s nothing I can do

But to love you both the more

Second best thing to a cure

These two songs feel like the difference between what a friend might tell you to do (“Call that bitch and tell her to back the hell off” — a la Jolene) and what a therapist might advise — “You can’t make someone stay with you — it takes two to be in a relationship — keep your perspective and remember this isn’t about you personally”.)

There’s room for both kinds of stories in this world. The question is, as a writer, which are you going for in any given narrative? Cathartic or nuanced? Expected or unexpected?

UNEXPECTED EMOTIONS IN SHORT STORIES

Now to the world of short stories.

Literary short stories are perhaps designated ‘literary’ precisely because of the nuanced, unexpected, unexplored Anagnorises and emotions from the main characters.

Alice Munro is a particularly nuanced writer, especially evident in the stories she wrote as an older person. Take the short story “Fiction” as a mentor text exploring the nuanced, unexpected emotions around infidelity.

There’s another unexpected emotional response in “Wigtime” (1989).

One of the most confronting sentences I’ve encountered in a short story is written by Cynthia Ozick for a Holocaust narrative called “The Shawl” which includes the death of a baby from hunger. The mother feels two things at once: joy and grief.

Every day Magda [the baby] was silent, and so she did not die. Rosa [the mother] saw that today Magda was going to die, and at the same time a fearful joy ran in Rosa’s two palms, her fingers were on fire, she was astonished, febrile: Magda, in the sunlight, swaying on her pencil legs, was howling.

“The Shawl” by Cynthia Ozick

AIM FOR UNEXPECTED EMOTIONS IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS

As children’s storytellers, be mindful of reaching for the easy, expected emotion. The ‘unexpected’ emotion in a children’s book — same as in stories for adults — is often the more muted one.

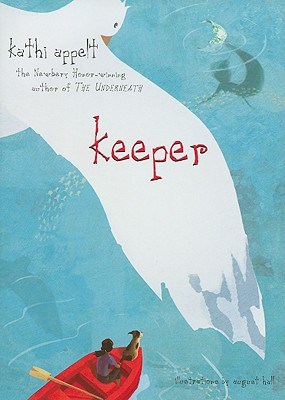

Keeper is a breathtaking, magical novel from National Book Award finalist and Newbery Honoree Kathi Appelt.

To ten-year-old Keeper the moon is her chance to fix all that has gone wrong … and so much has gone wrong.

But she knows who can make things right again: Maggie Marie, her mermaid mother, who swam away when Keeper was just three. A blue moon calls the mermaids to gather at the sandbar, and that’s exactly where Keeper is headed – in a small boat. In the middle of the night, with only her dog, BD (Best Dog), and seagull named Captain. When the riptide pulls at the boat, tugging her away from the shore and deep into the rough waters of the Gulf of mexico, panic sets in and the fairy tales that lured her out there go tumbling into the waves. Maybe the blue moon won’t sparkle with mermaids and maybe – Oh, no … “Maybe” is just too difficult to bear.

Below, Betsy Bird makes special note of a children’s book which makes an excellent job of portraying the complex emotion of guilt. It it’s a lot easier to write about tantrums (or ‘snits’), and let’s face it, more fun. I have covered numerous examples of picture books featuring snits/tantrums on this blog, but middle grade novel Keeper by Kathi Appelt knows that middle grade readers are ready for something a little more complex:

There is a note at the back of this book in the Acknowledgment section that strikes me as just as important as any word in the text itself. Writes Ms. Appelt of one Diane Linn, “She lovingly cast her knowledge of tides and currents and stingrays my way, and she asked me to consider heartbreak over anger.” Heartbreak over anger. The very root of why Keeper goes traipsing out into the sea in a boat with only a dog by her side. Any book, heck most books, would have sent Keeper into that boat in the midst of a snit. Kids understand snits. They’re experts in `em. But while a snit may help your plot along, it isn’t as emotionally rewarding as good old-fashioned guilt. Keeper goes into that boat not because she’s mad or even because she feels much affection for her absent mother, but because she’s wholly convinced that she’s ruined the lives of everyone she loves and this is the only way to rectify the situation. That packs the necessary emotional wallop the book requires, while also making Keeper a sympathetic character. Well played, Diane Linn.

review of Keeper by Diane Linn, reviewed by Betsy Bird

Photo in header is by Allef Vinicius.