There are many things that date a children’s book — racism, sexism and other -isms are widely discussed and relatively easy to pick. I know that when I re-read Enid Blyton or almost anything from The First Golden Age of Children’s Literature these things stick in my craw.

Other aspects are a little more subtle. Take the expression of emotions. Until recently, children in the West (especially boys) were uniformly required to keep their emotions in check — the younger the better. If you’re my age or older, you probably remember being told to stop crying. You were told, ‘It’s not worth crying over,’ or ‘Don’t cry over spilt milk.’

Psychologists now know it is unhelpful to persuade a child not to feel an emotion which they are very much feeling. If we want to teach emotional literacy we must name emotions when they occur. We can’t be afraid of them.

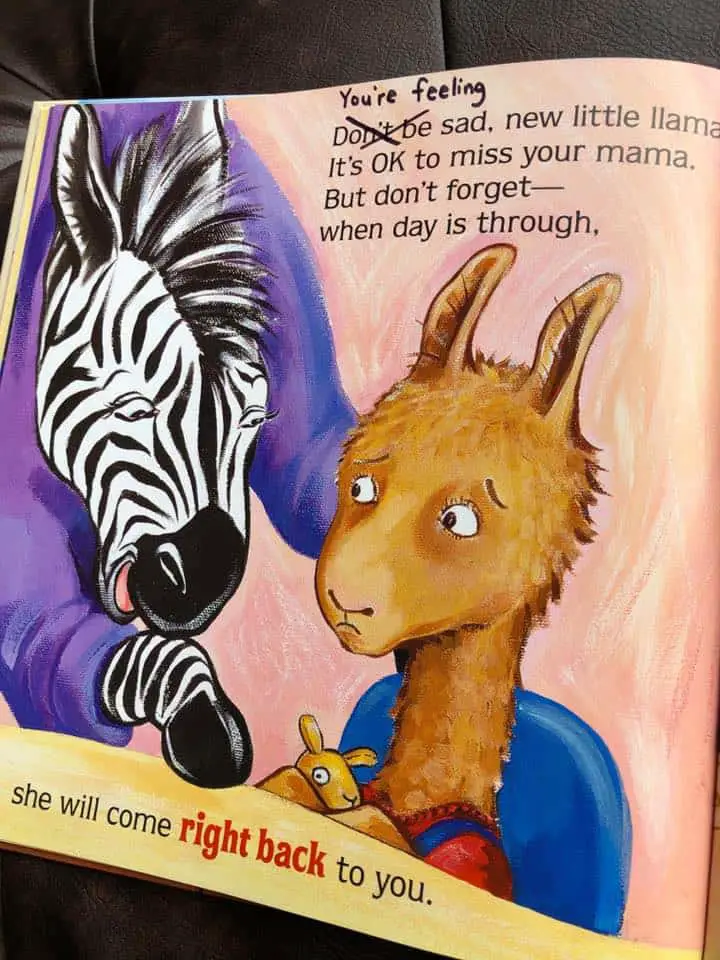

Yet picture books are still not fully reflecting this change, especially if we’re still reading books more than 10 or 15 years old to our kids. In this case, we may want to edit them ourselves.

The following photos are plucked from Generation Mindful’s social media stream — a small organisation whose mission is to improve emotional literacy and mental health, especially in children.

EXAMPLE ONE

When emotions are denied in picture books, edit in favour of acknowledgement.

Sesame Street has made a wonderful contribution towards teaching emotional literacy. In the image below, everyone at the park is happy except Bert. Books from the First Golden Age of children’s literature tell children to smile, regardless of how they feel. But Bert is allowed to have his feelings.

Australian cartoon series Bluey is also very good at letting children live with their feelings.

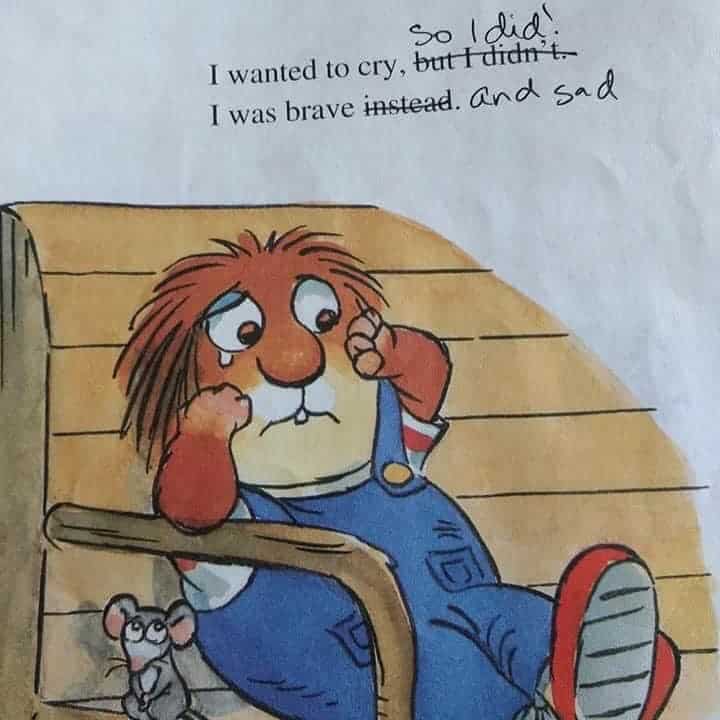

EXAMPLE TWO

It’s important children learn it’s possible to feel more than one emotion at the same time. When child characters in picture books are rewarded for not crying, edit to allow for crying. This is especially important for boy characters.

At the risk of sounding like a ‘don’t cry’ apologist, I believe earlier generations were in part attempting something akin to the ‘opposite action‘ technique when they advised their children not to cry. It wasn’t called that then, but you can observe the grandmother in Katherine Mansfield’s “At The Bay” practising something similar. Katherine Mansfield was interested in the vitalists and had done a lot of reading on popular psychology of the time. According to this line of reasoning, you privately acknowledge what you feel, but then you behave in the way you want to be feeling. So, if you’re feeling really down and are inclined to spend the day in bed, you really need to get out of bed and do something you normally love. This can help you to feel better. We might assume that smiling when you feel like crying really can make you feel better.

Crucially, opposite action only works when the emotion doesn’t fit the situation. And the very first step in the opposite action technique is identifying the uncomfortable emotion.

Part of the problem with telling children not to cry is that we may also be telling them they have no reason or right to feel that uncomfortable emotion. Boys who are not allowed to feel sad can learn after some years to turn any negative emotion into anger — the only ‘acceptable’ masculine emotion. This has devastating consequences for everyone.

EXAMPLE THREE

The following text is all round unhelpful. Sometimes the very premise of a story is unhelpful. The following edit works for the page, but I suspect it changes the entire dynamics:

“Are you frightened?” asked Fuzzy and Scratchy.

“The cricket does look a little bit scary. We’re frightened, too.”

THE MIDDLE CLASS ASSUMPTION ABOUT BOYS AND CRYING

As you may have noticed, children’s books cater most adequately to the book-buying middle class. This has been the case since the end of oral narrative, as soon as stories started being printed out and sold, to people with money to spare.

To quote feminist philosopher Kate Manne on Twitter:

It is an unquestionable trope of white middle-class parenting that boys must be prevailed upon to feel & show their emotions. But what if this isn’t much of a—or isn’t quite the—problem? What if girls need to be similarly encouraged? What if white boys need to show less anger?

Dr. Manne also shared a study called Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Yes, people are studying this stuff.

And here’s Manne’s response to that:

It’s often taken for granted that boys/men don’t—or aren’t permitted to—cry. What is the evidence for this, exactly? This recent meta-analysis suggests differences in the emotional expressions of boys vs. girls are small and subtle.

In children’s books as in everything else, we may need to examine our himpathy.

MEN AND CRYING BEFORE THE 20TH CENTURY

Someone else on the same thread made the following observation:

I can’t say it’s very scientific but I’m always struck when reading 18th/19th Century novels (men and women authors) by how much the men cry to express extremes of emotion. It’s not really made a meal of – just something the authors feel is relatively normal for them to do.

I can’t say I’ve noticed this myself, but I may not have read enough 18th and 19th century novels. If true, this suggests that the phenomenon of repressed emotion was a temporary blip lasting the length of the 20th century, and not a long-standing feature of humanity. We are perhaps now returning to a cultural norm in which it is acceptable to express certain emotions, for all genders.

We can expect to see this trend in children’s books.

TEACHING EMOTIONAL LITERACY USING CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Throughout the history of children’s literature, children’s books have existed in large part to teach lessons. Not only do they teach children to be compliant, grateful, pious, and to work hard, children’s books socialise children. Today we might say they teach ’emotional literacy’.

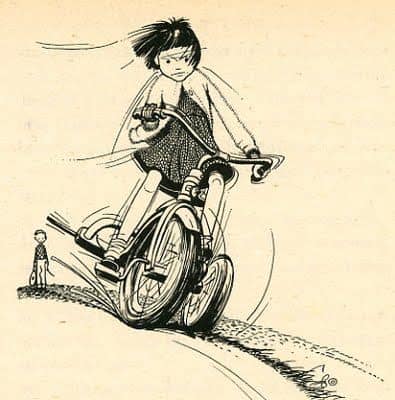

“Everybody else on the block rides two-wheelers. Only babies ride tricycles.” She made this remark because she knew Howie still rode his tricycle, and she was so angry about the ribbon she wanted to hurt his feelings.

Ramona the Pest, Beverly Cleary

Adult readers are left to work out motivations, ironies and desires for ourselves — we read between the lines. And this is true for young adult novels, too. But when children are learning to read they are also learning to recognise and name their feelings. Chapter books such as the Ramona series are good at doing that because they add that little extra bit of explanation.

This little bit of extra explanation can be found in children’s books for older readers, too:

“So you should have told me before, that’s what. You shouldn’t hide things like that from people, because they feel stupid when they find out, and that’s cruel.“

Northern Lights, Philip Pullman (Lyra to her father)

When an adult is unable to identify their own feelings it’s called alexithymia.

Alexithymia is defined by:

- difficulty identifying feelings and distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal

- difficulty describing feelings to other people

- constricted imaginal processes, as evidenced by a scarcity of fantasies

- a stimulus-bound, externally oriented cognitive style.

Alexithymia is found more commonly in the autistic population, but not all autistic people have trouble understanding and identifying emotions. In fact, only about one in two autistic people have trouble with this.

Likewise, a surprisingly high 10 percent of non-autistic individuals are alexithymic.

Reading and understanding complex and difficult emotions are skills that need to be learned by all of us. Another reason not to skip the chapter books!

While Beverly Cleary does it beautifully, it’s easy to name emotions badly.

I’ve noticed a tendency in children’s books to describe the feeling of an emotion without using the word commonly associated with that emotion. A classic example is repeated like a chorus through the picture book Hannah and the Seven Dresses.

Hannah, with her closet full of dresses handmade by her mother, breaks out in a sweat when she has to decide which to wear: “”Her face got hot. She shivered all over. Her knees went jiggly and her toes curled under.”

from the Publishers Weekly review

These physiological reactions are described but not named.

The reason I advocate for naming as well as describing emotions in children’s stories is because attaching feelings to descriptive words is a learned skill, a difficult skill, alexithymia or no, and children’s writers needn’t shy away from it.

FURTHER READING

Dark feelings will haunt us until they are expressed in words from Psyche

The teaching of emotion differs across cultures, and this difference can be seen in children’s books. In the West, we tend to conceptualise emotions as happening in the heart. The picture book In My Heart: A Book of Feelings by by Jo Witek and Christine Roussey is a classic Western example.

In other parts of the world, such as Japan, emotions are thought to happen in the stomach. A Japanese picture book, then, will be different.

RELATED

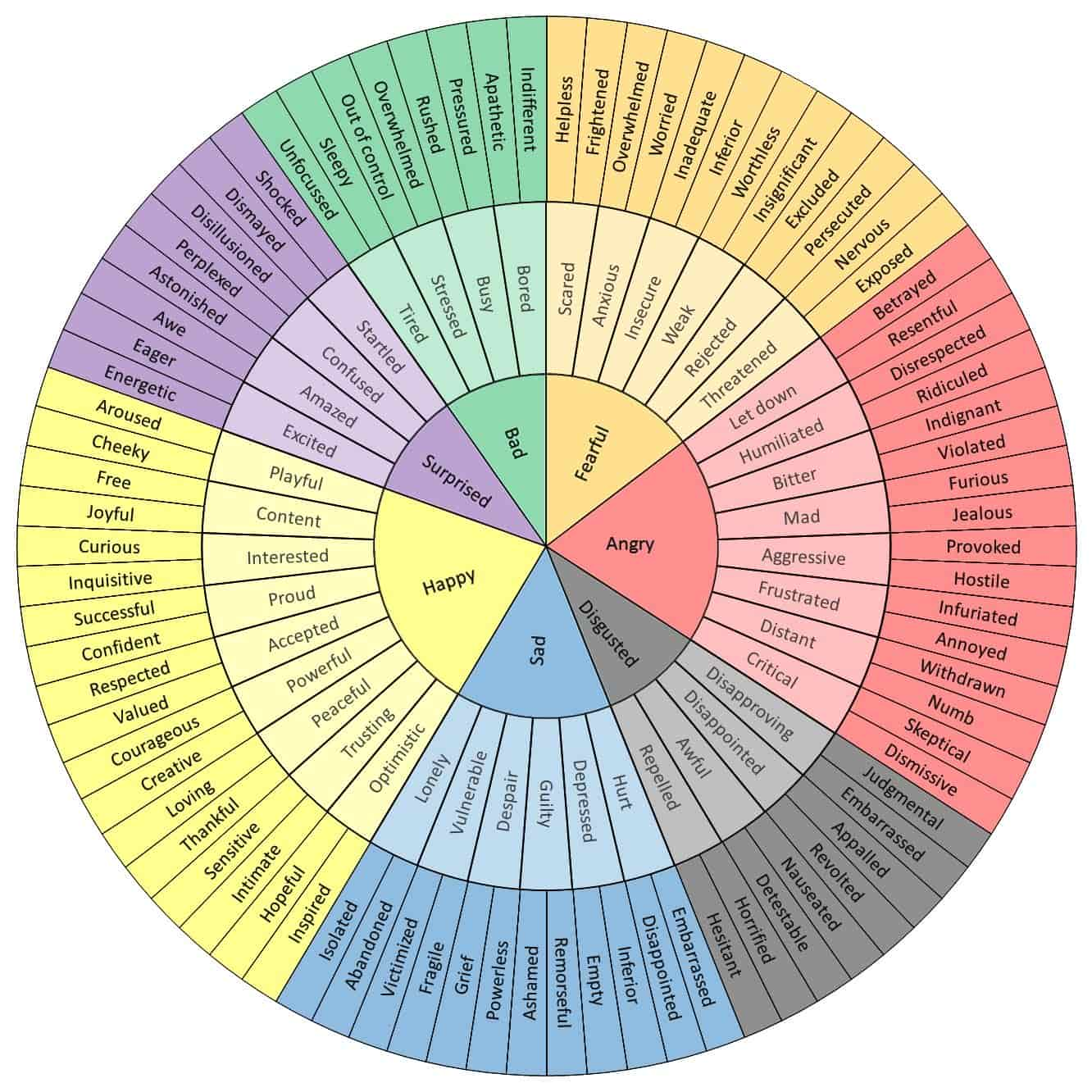

The Feel Wheel is a graphic by Geoffrey Roberts which helps people to be specific about how we are feeling and express it to others.

Header photo by Kat J