Read a modern re-telling of “The Elves and the Shoemaker” and you might conclude it’s a tale in praise of gratitude: Gratitude is noble. If someone does you a kind turn, be nice in return.

But that was not the takeaway message for earlier audiences of this tale, told to people with a very different, supernatural worldview. Back when people sort-of-really did believe in fairies, “The Elves and the Shoemaker” tales offered a warning: Do not, whatever you do, make clothes for fairies. DO NOT DABBLE IN ELF-CRAFT. DO NOT ENCOURAGE THEM INTO YOUR HOME.

14th-century English saint, John Schorne, may have been the source of the belief that shoes had the power to protect against evil. Schorne was said to have succeeded in trapping the Devil in a boot, a legend that may have its origin in a more ancient folk belief, which the Church was attempting to convert into an “approved Christian rite”.

Wikipedia

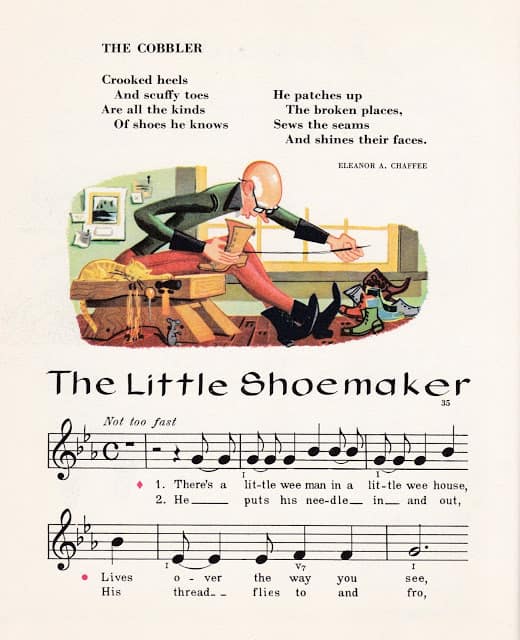

SHOES AND FAIRYTALES

Across separate narratives, elves and hobgoblins have a strong association with shoes.

SMALL HELPFUL CREATURES IN THE HOME

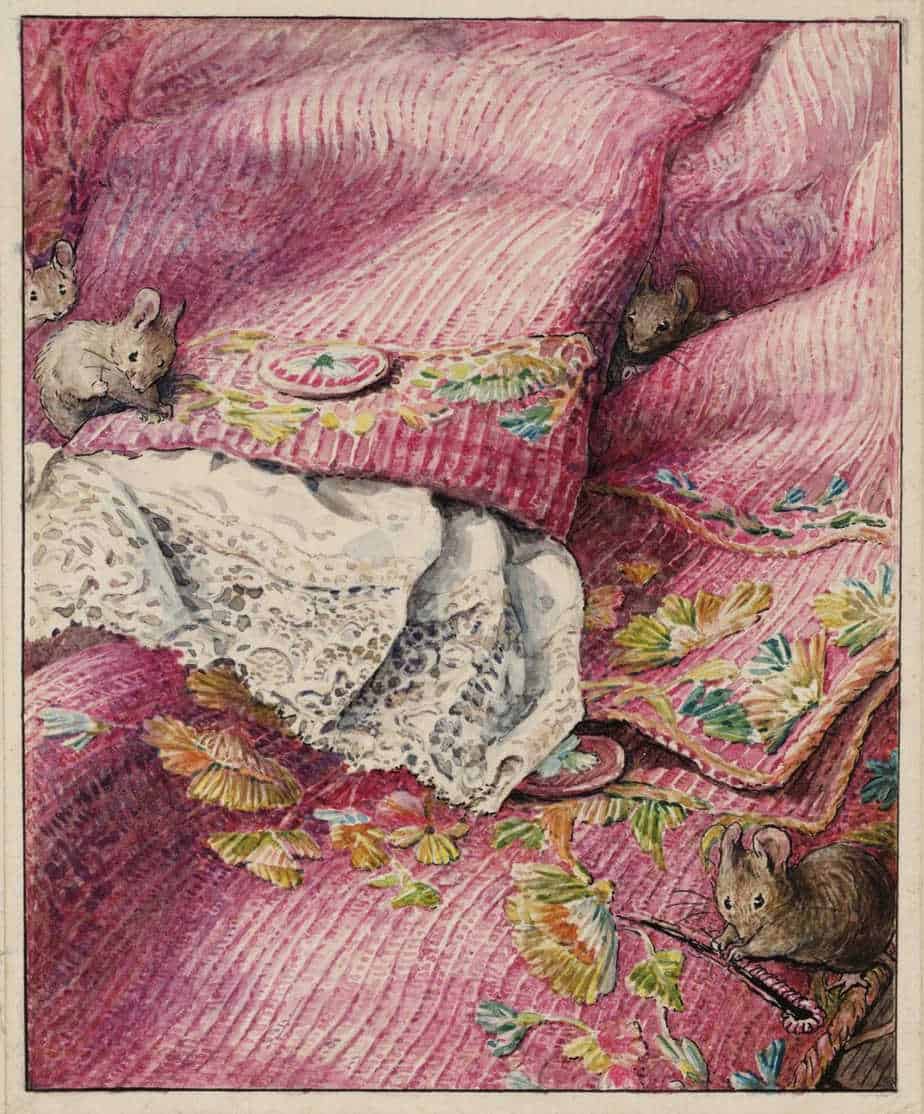

Likewise, there’s a long history of ideas about small creatures entering the home and carrying out monotonous tasks. I believe this is a common wish fulfilment fantasy common to women, especially to housekeepers and wives.

Small creatures doing your housework:

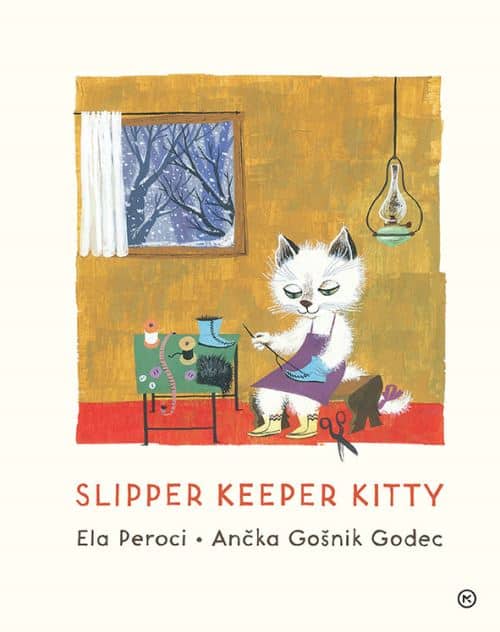

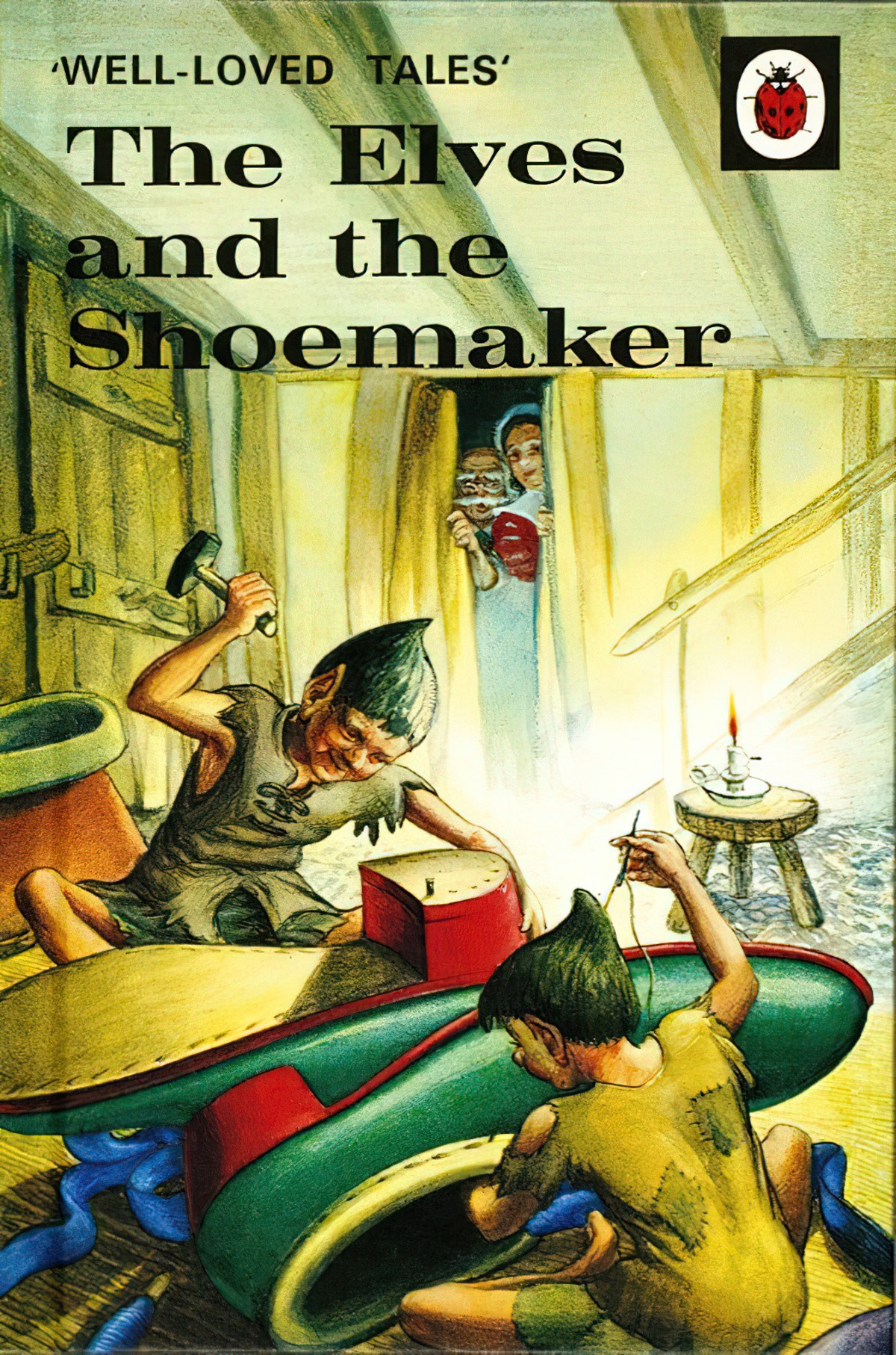

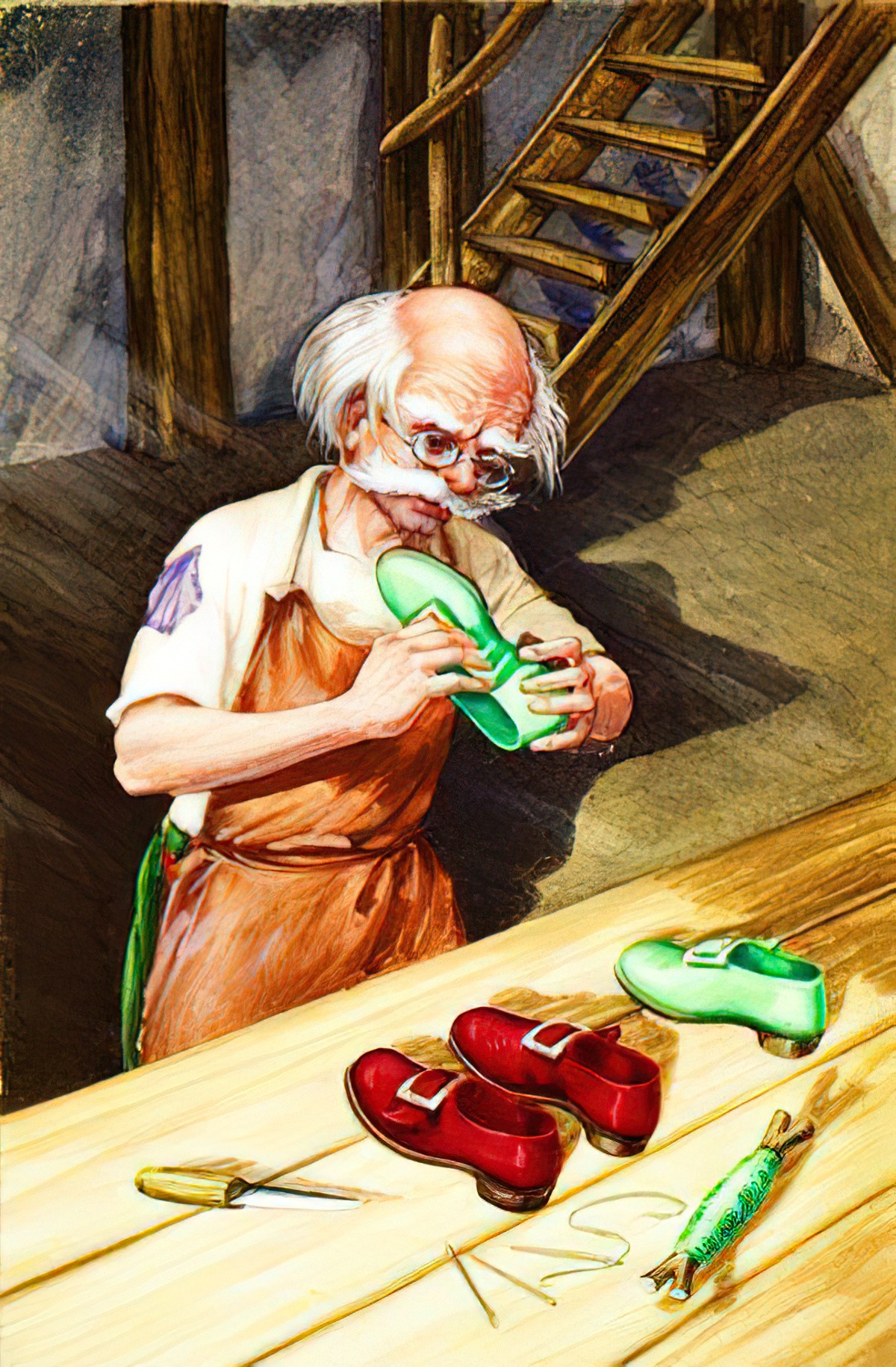

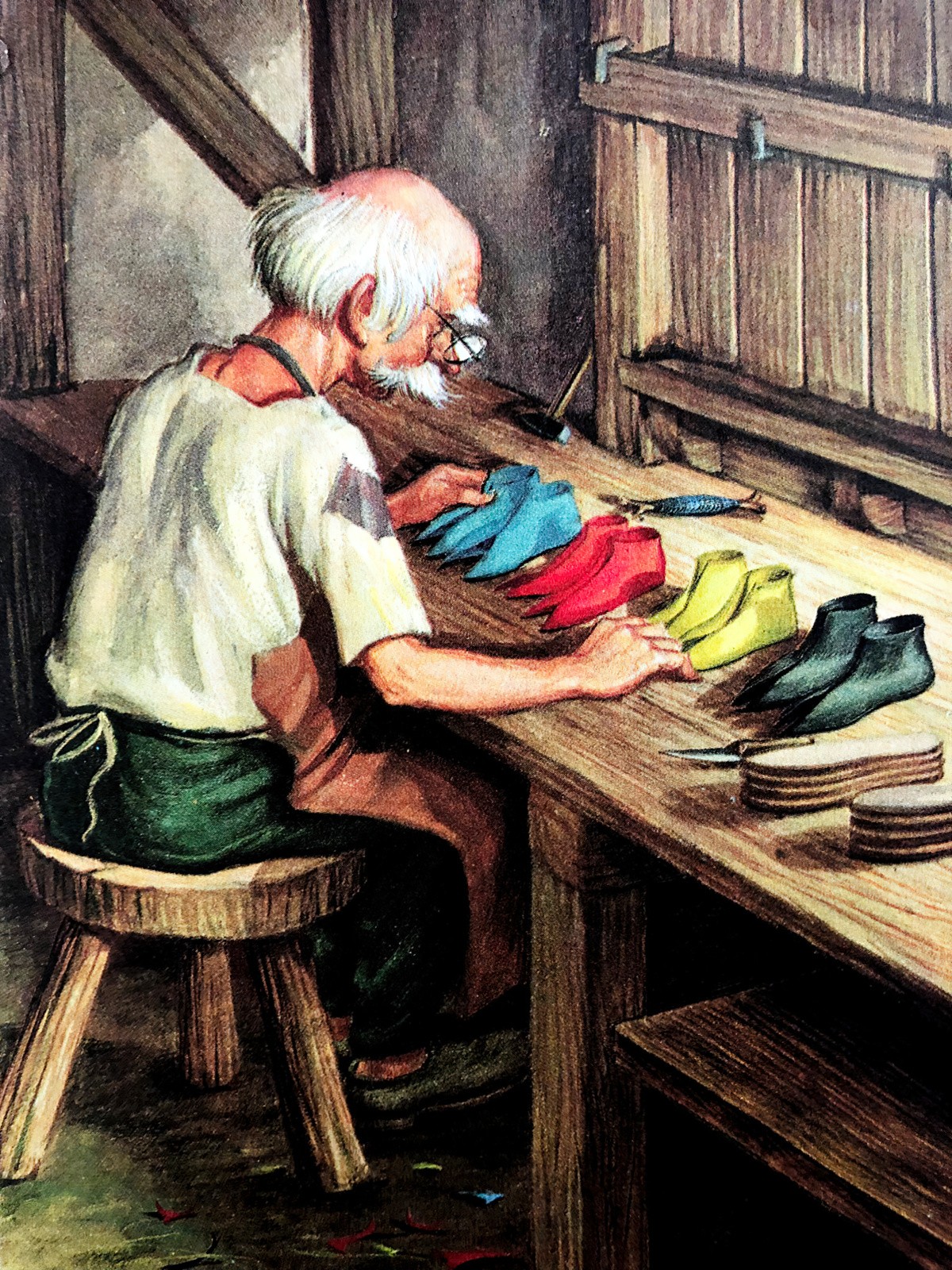

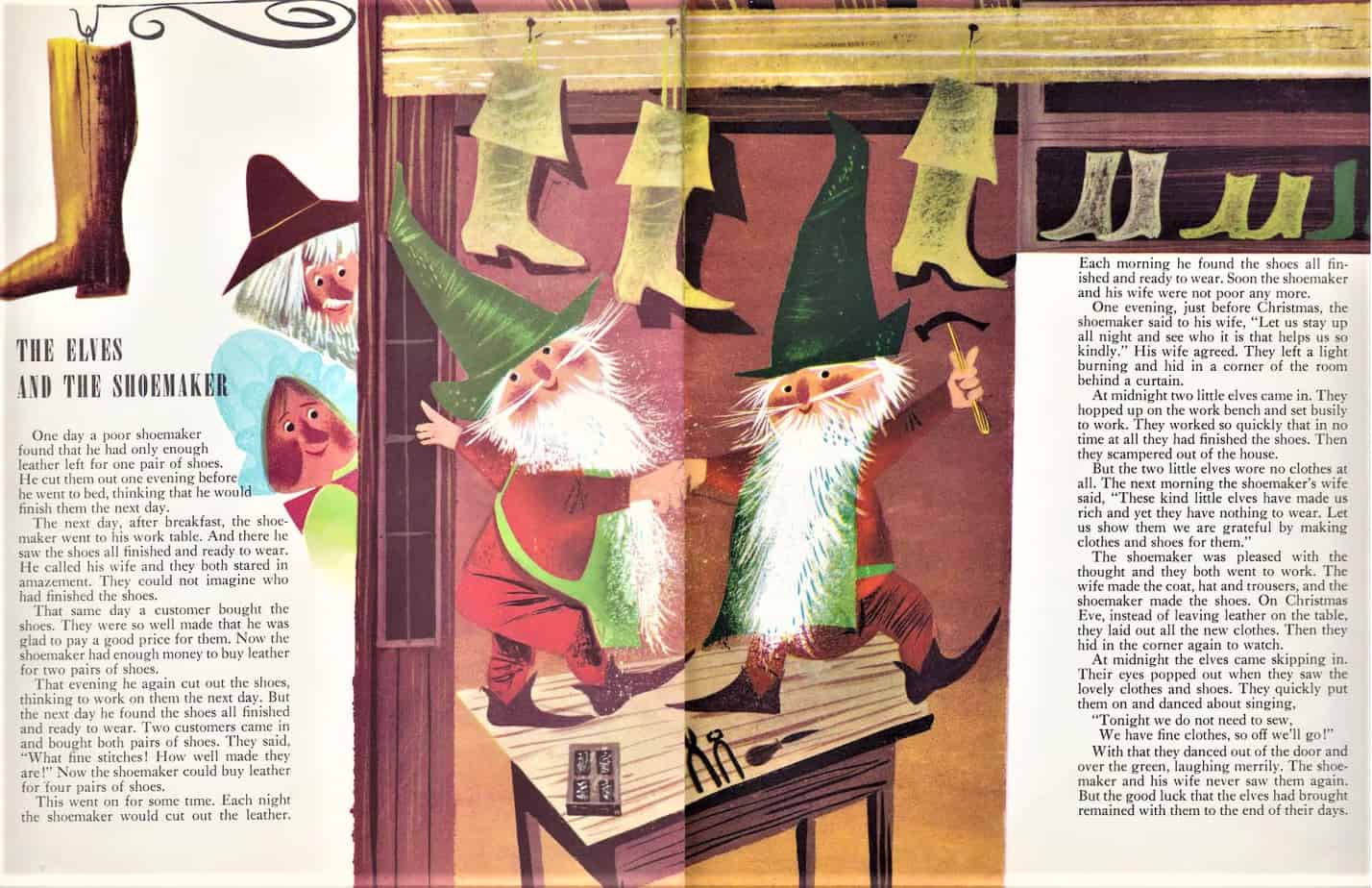

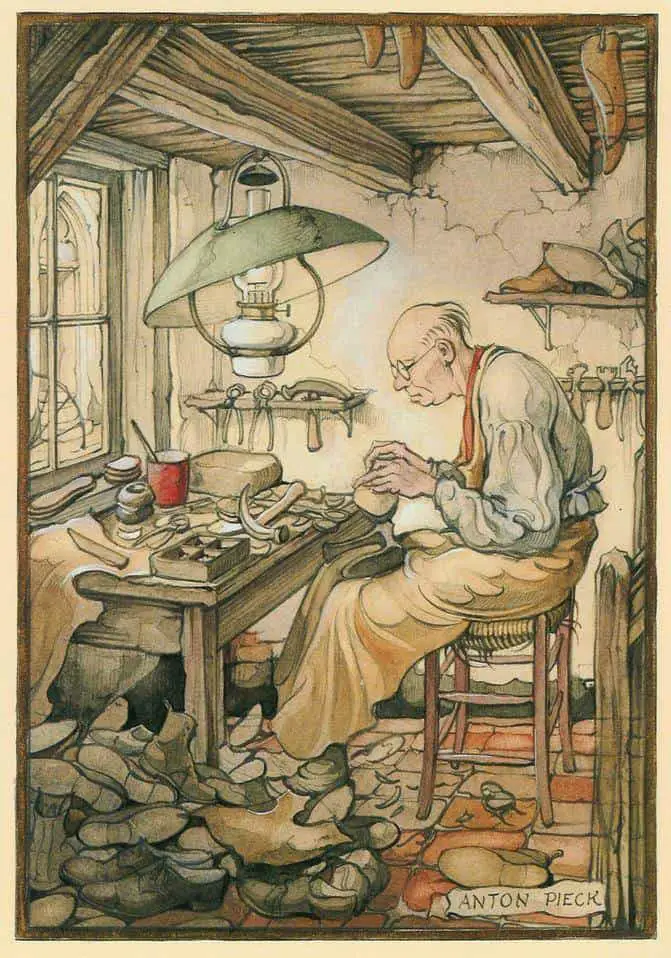

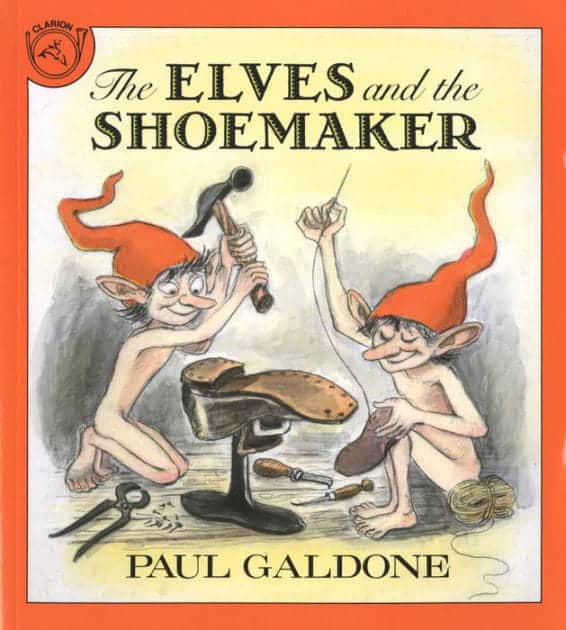

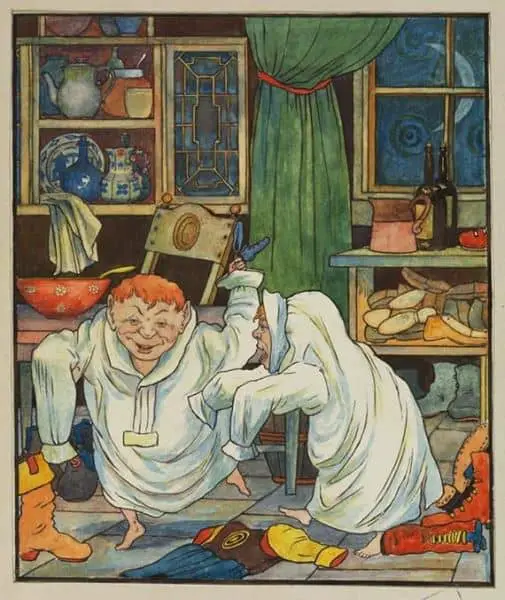

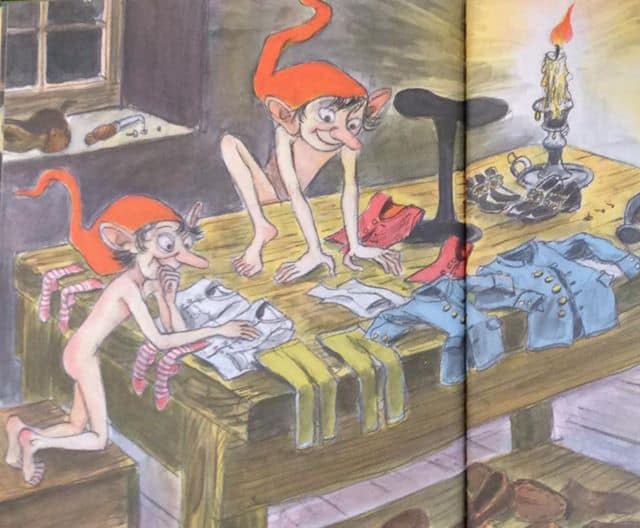

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ELVES AND THE SHOEMAKER

THE ELVES AND THE SHOEMAKER, GRATITUDE VERSIONS

The Grimms called the story “Die Wichtelmänner”.

There was once a shoemaker, who worked very hard and was very honest: but still he could not earn enough to live upon*; and at last all he had in the world was gone, save just leather enough to make one pair of shoes.

* By the time the Grimms collected “The Elves and the Shoemaker”, the fortune of shoemakers had dropped considerably. They were competing with factory made shoes, made much more cheaply. Shoemakers in the medieval era were very well-off, and employed many staff. They were the bosses of their own small businesses. It’s quite likely an old shoemaker living in the mid 1800s would feel unfairly disadvantaged and cranky. Schuster’s father and grandfather both would have been much better off, doing the same work.

In some versions of the tale, storytellers insert a Save the Cat moment to make the shoemaker even more empathetic. He gives away the last pair of shoes he has to a needy lady. Then he uses the money from the final shoes to pay the rent, buy food and more shoe leather. He also feeds a poor traveller. This makes the shoemaker a worthy recipient of good fortune, and a story which says, “Be generous and you will be rewarded in kind.”

Then he cut his leather out*, all ready to make up the next day, meaning to rise early in the morning to his work.

* As late as 1850 the shoes were made on straight lasts, with no difference between the left and right foot. (Lasts are bits of wood in the shape of a foot.) Breaking in a new pair of shoes was not easy. There were but two widths to a size; a basic last was used to produce what was known as a “slim” shoe. When it was necessary to make a “fat” or “stout” shoe the shoemaker placed over the cone of the last a pad of leather to create the additional foot room needed.

His conscience was clear and his heart light amidst all his troubles; so he went peaceably to bed, left all his cares to Heaven, and soon fell asleep. In the morning after he had said his prayers, he sat himself down to his work; when, to his great wonder, there stood the shoes all ready made, upon the table. The good man knew not what to say or think at such an odd thing happening. He looked at the workmanship; there was not one false stitch in the whole job; all was so neat and true, that it was quite a masterpiece.

The same day a customer came in, and the shoes suited him so well that he willingly paid a price higher than usual for them; and the poor shoemaker, with the money, bought leather enough to make two pairs more. In the evening he cut out the work, and went to bed early, that he might get up and begin betimes next day; but he was saved all the trouble, for when he got up in the morning the work was done ready to his hand. Soon in came buyers, who paid him handsomely for his goods, so that he bought leather enough for four pair more. He cut out the work again overnight and found it done in the morning, as before; and so it went on for some time: what was got ready in the evening was always done by daybreak, and the good man soon became thriving and well off again.

One evening, about Christmas-time, as he and his wife were sitting over the fire chatting together, he said to her, ’I should like to sit up and watch tonight, that we may see who it is that comes and does my work for me.’ The wife liked the thought; so they left a light burning, and hid themselves in a corner of the room, behind a curtain that was hung up there, and watched what would happen.

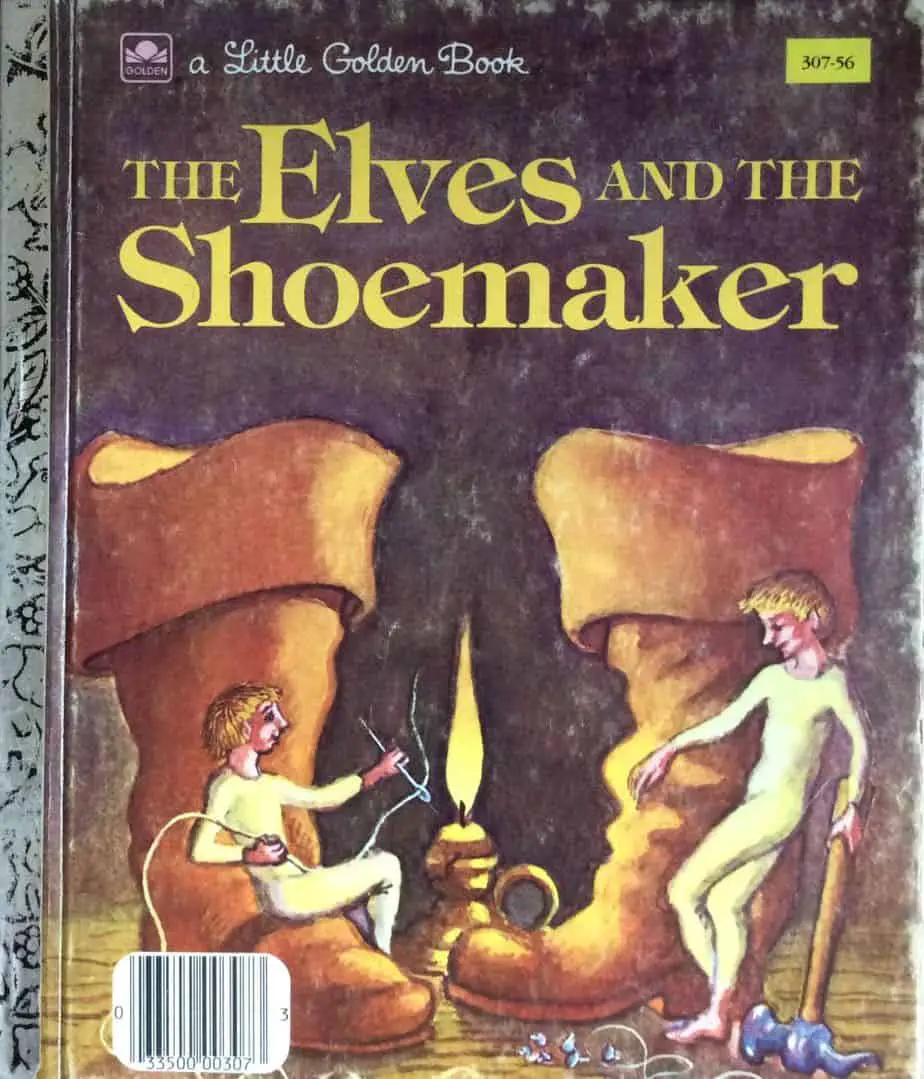

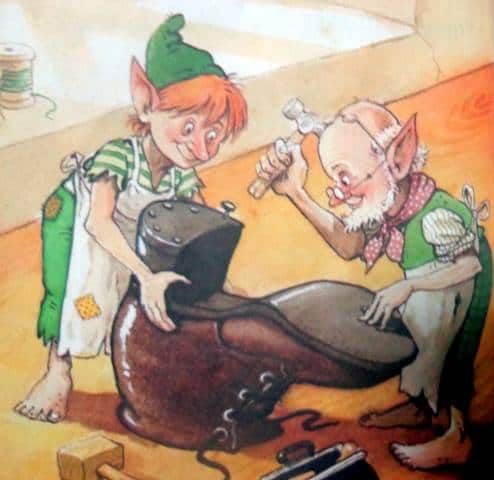

As soon as it was midnight, there came in two little naked dwarfs; and they sat themselves upon the shoemaker’s bench, took up all the work that was cut out, and began to ply with their little fingers, stitching and rapping and tapping away at such a rate, that the shoemaker was all wonder, and could not take his eyes off them. And on they went, till the job was quite done, and the shoes stood ready for use upon the table. This was long before daybreak; and then they bustled away as quick as lightning.

The next day the wife said to the shoemaker. ’These little wights* have made us rich, and we ought to be thankful to them, and do them a good turn if we can. I am quite sorry to see them run about as they do; and indeed it is not very decent, for they have nothing upon their backs to keep off the cold. I’ll tell you what, I will make each of them a shirt, and a coat and waistcoat, and a pair of pantaloons into the bargain; and do you make each of them a little pair of shoes.’

* a spirit, ghost, or other supernatural being (Archaic dialect). From Dutch wicht, meaning little child and in German, ‘creature’.

The thought pleased the good cobbler very much; and one evening, when all the things were ready, they laid them on the table, instead of the work that they used to cut out, and then went and hid themselves, to watch what the little elves would do.

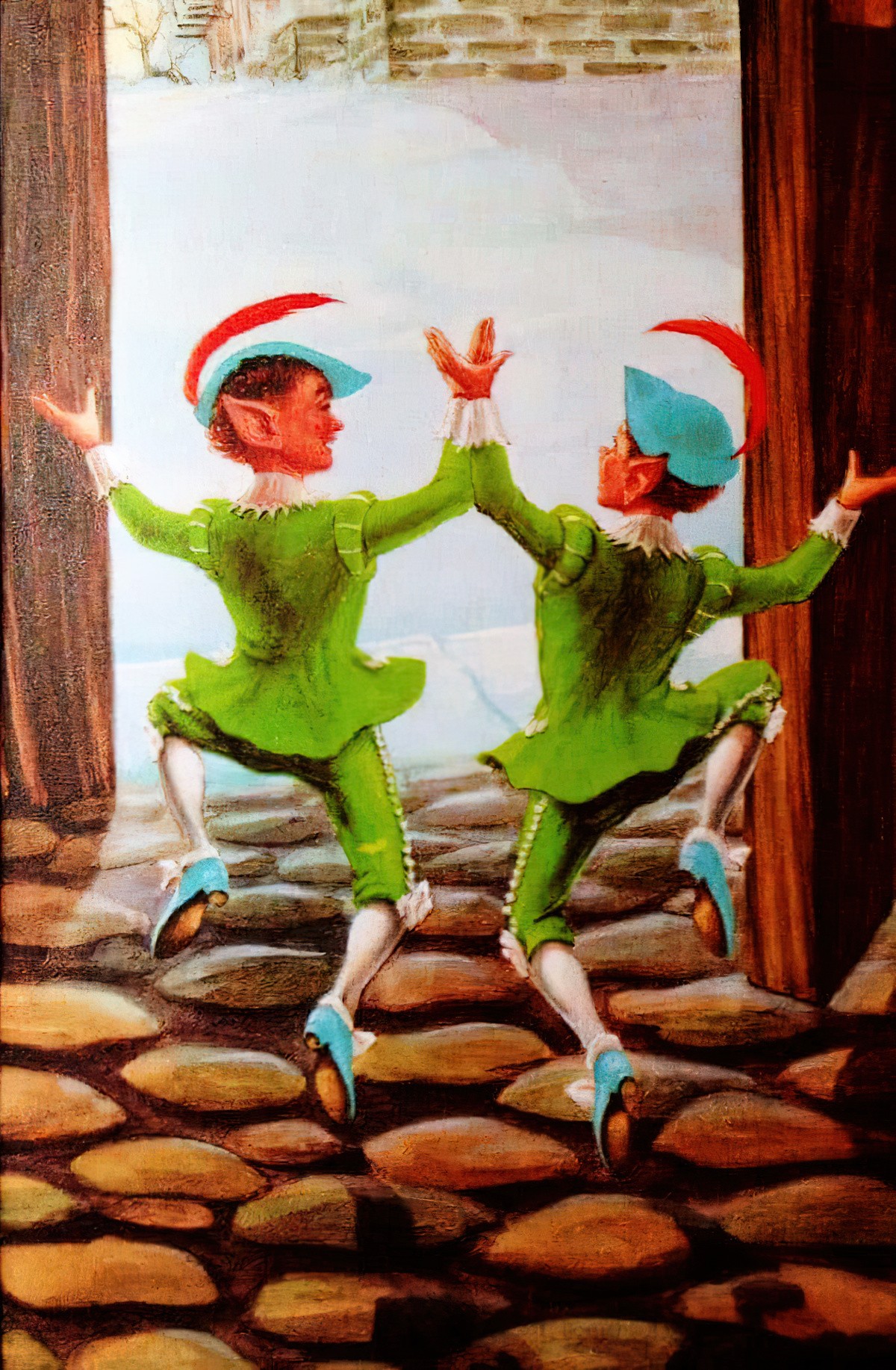

About midnight in they came, dancing and skipping, hopped round the room, and then went to sit down to their work as usual; but when they saw the clothes lying for them, they laughed and chuckled, and seemed mightily delighted.

Then they dressed themselves in the twinkling of an eye, and danced and capered and sprang about, as merry as could be; till at last they danced out at the door, and away over the green.

The good couple saw them no more; but everything went well with them from that time forward, as long as they lived.

In the American The Peachy Cobbler cartoon adaptation from 1950, emphasis falls upon the carnivalesque gags of the elves making the shoes. Aside from this difference, The Peachy Cobbler is another version in which a kind shoemaker feeds some birds and is rewarded when the birds turn out to be helpful elves.

THE ELVES AND THE SHOEMAKER, DARKER VERSION

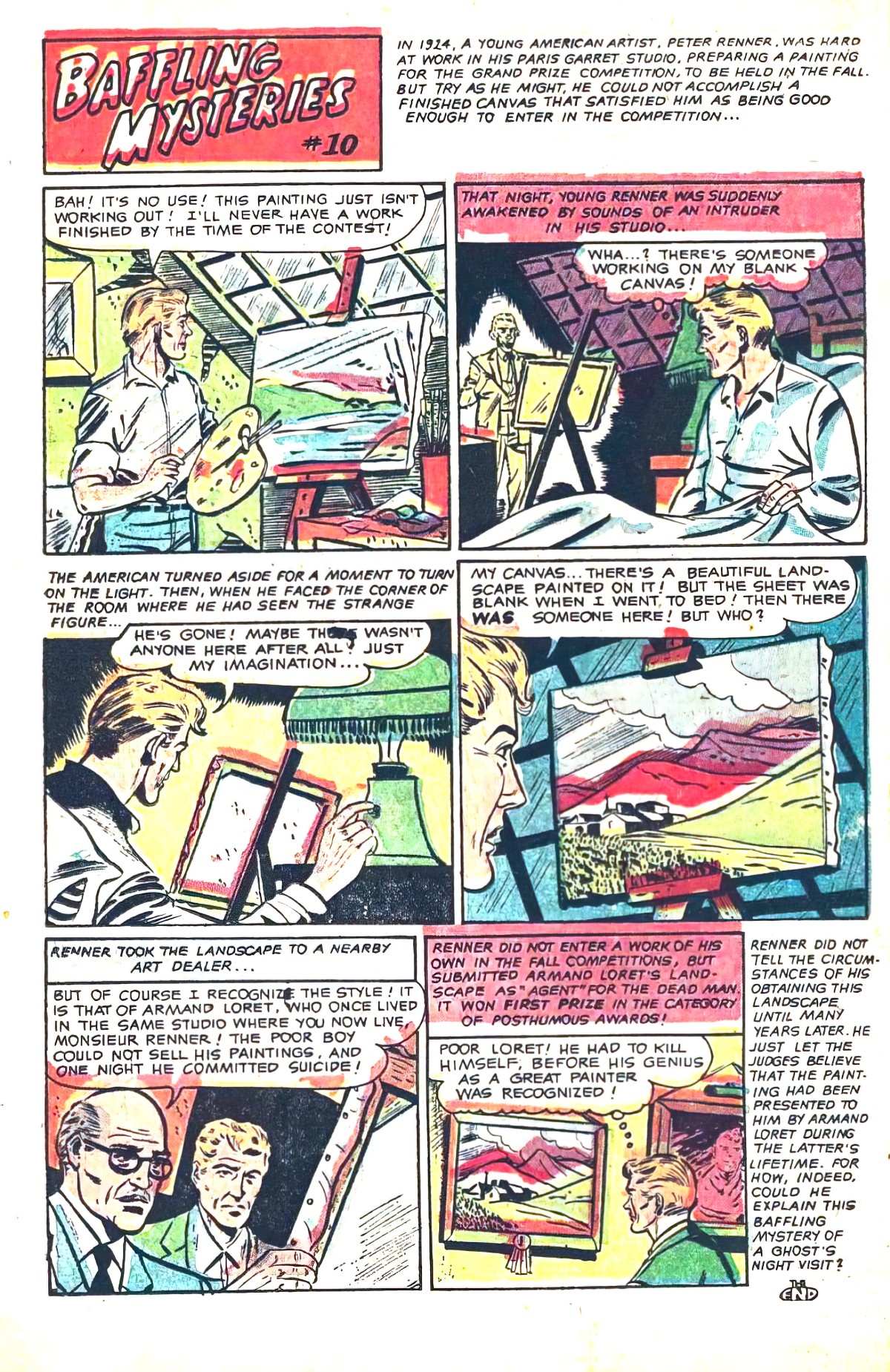

Let’s take a look at earlier versions of the shoemaker fairytale, for instance “The Dwarf As A Journeyman Shoemaker“.

The evolution of “The Elves and the Shoemaker” is probably to do with the changed fortune of your typical European shoemaker over time. Shoemakers known by the Grimm Brothers would’ve lived humble, unadorned lives, but this differed from the fortune of shoemakers in the Medieval era. In Medieval times a shoemaker was both a skilled craftsman and a merchant of some status. He was capable of acquiring some wealth. By the way, Medieval shoes were more like slippers than like shoes as we know them today. Fashionable ladies wore goatskin leather or cordwain (a fine leather originally made by the Moors of Cordova). This is even less study than ordinary cowhide.

Interesting backstory for the version below: Shoemakers required awls for punching holes in leather; hot burnishers that rubbed soles and heels to a shine; sole knives that shaped soles; stretching pliers which stretched the leather uppers; marking wheels to mark where the needle should go through the sole, and size sticks to measure the foot. By 1750 shoemakers were making shoes in different sizes for anyone who wanted to buy them. Before that they only made shoes on special order.

Unlike some other guilds, grain merchants, ale brewers, goldsmiths, greengrocers and shoemakers are allowed to take a good number of apprentices (some only allow one). A middle ground between a master and an apprentice would be a journeyman. These guys were hired partly to stop them providing competition as standalone craftsmen.

A dwarf came to shoemaker and offered his services as a journeyman. The shoemaker had a lot of work at the time and was therefore happy to accept the offer. He asked what he expected for wages. The dwarf asked for twenty-four thalers* per week. The shoemaker replied that that was a lot of money, and that the dwarf was very small. How much work would he be able to do?

* A thaler is a German silver coin.

“Yes,” said the dwarf. It was a lot of money, but his work would be worth it. Each week he would be able to make twenty-four pair of tall riding boots. So the shoemaker hired him.

The next morning the dwarf did not begin to work but instead made himself comfortable and walked around in the house. The shoemaker reminded him of his promise, and the dwarf answered that he would keep it, but did nothing. Saturday arrived, and this day passed as well with the dwarf doing no work.

That night at eleven o’clock there arose a commotion in the house, and suddenly it was full of dwarfs. The shoemaker, who had already gone to bed with his wife, heard the noise and became curious. He looked through the keyhole and saw a roomful of dwarfs. Some were cutting and some were stitching while the journeyman sat comfortably in their midst and smoked.

Suddenly one of the dwarfs said, “Master, he’s looking!”

“Let him look!” was the answer.

The dwarf repeated this three times, and the fourth time the answer was, “Then poke his eye out!”

With that the dwarf poked out the shoemaker’s eye with an awl.

The latter went to his wife and told her what he had seen and what had happened to him. His wife advised him to not go back.

The dwarfs’ work lasted until one o’clock, and then everything was quiet.

The next morning the wife got up and gave the journeyman his twenty-four thalers and told him he could go. The latter asked where the master was; he wanted to speak with him.

The wife answered that that was not possible, for the master was ill.

The dwarf asked, “What is wrong with him?”

“I don’t know,” she answered.

The dwarf insisted that she call her husband. Perhaps he could help him. So finally she fetched her husband.

The dwarf asked the shoemaker what was wrong with him, and he answered that he had seen the dwarfs at work and told what had happened to him.

With that the dwarf blew into his eye, with the words, “Next time don’t look!”

And in that instant the shoemaker could again see with his eye.

Dark as it is, the story ends happily (though not wonderfully) with the shoemaker’s eyesight restored. However, the message is clear: If you interact with supernatural creatures and invite them into your home, you’re cruising for a bruising.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE ELVES AND THE SHOEMAKER”

PARATEXT

The marketing copy of modern editions for children go something like this:

An adaptation of the classic tale in which a poor old shoemaker becomes successful with the help of two elves who finish his shoes during the night.

SHORTCOMING

In the Grimm version, the shoemaker has no moral shortcoming. Conversely, he is rewarded for his generosity. (The reward is completely disproportionate.)

In earlier, darker versions, the shoemaker will be temporarily punished for allowing supernatural creatures into his home, so his shortcoming is lack of foresight around this.

DESIRE

In gratitude versions, the shoemaker has no strong desire other than to make a living and support himself and his wife. (No children of their own are mentioned. I wonder if childless couples in folk and fairy tale were more likely to be visited by proxy children, i.e. elves, goblins and fairies.)

OPPONENT

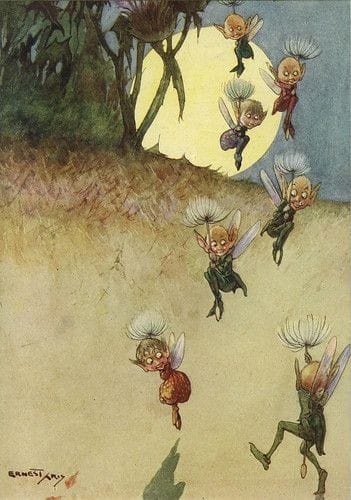

Though translators use various related words when referring to human creatures of very small size, the ‘elves’ in this fairy tale are technically ‘hobgoblins’. Hobgoblins live in the house. Brownies are similar. This category of fairy was considered extremely capricious, their motives unfathomable. If you left them alone to get on with things they would continue to help you out. But as soon as you thank them or do them a good turn they were liable to take their services elsewhere. “No, really, don’t thank me!” is the hobgoblin’s catch cry, followed by, “I’m leaving!”:

Hemton hamten, here will I never tread nor stampen!

That’s a quote from Reginald Scott, Discoverie of Witchcraft, 1584, p. 85, who was trying to stop the persecution of witches but who also thought unicorn horns were medicinal.

Nowadays, the elves of this classic tale are depicted differently depending on the degree of bowdlerisation required by the publisher. In the illustrations below, those by George Roland Halkett remind me of the sinister child figures of Maurice Sendak, while the skinny, naked elves wearing only hats have the bodies (and flexibility) of playful five year olds.

The elves in gratitude versions of the story turn out to be allies, whereas the hobgoblins of earlier versions are dangerous and, yes, capricious would be the word.

PLAN

Hard work and humility is rewarded. Note that in the gratitude versions the Christianity runs strong. The shoemaker prays piously and whatnot. The ideology of rich reward for hard work runs strong in the Christian tradition.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

In gratitude versions, the scene of the elves making the shoes is carnivalesque. The audience takes delight in imagining or seeing tiny creatures making shoes.

The darker version above features a more traditional battle scene in which the shoemaker loses an eye.

ANAGNORISIS

Since the gratitude message is central to the Grimms’ didactic tale, the anagnorisis is meant for the reader: If I work hard and remain humble then I too might be rewarded richly. Maybe not by ‘elves’, but by ‘the universe’.

NEW SITUATION

Everyone is happy and rich.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

The kind and generous shoemaker will be rich forevermore. We’re to imagine the shoemaker will continue to share his spoils by giving shoes away, though more recent psychological research shows what we can all abase ourselves by looking at the richest of the rich in the era of late capitalism: Simply being rich makes a person lose empathy for others.

Who is more likely to lie, cheat, and steal—the poor person or the rich one? It’s temping to think that the wealthier you are, the more likely you are to act fairly. After all, if you already have enough for yourself, it’s easier to think about what others may need. But research suggests the opposite is true: as people climb the social ladder, their compassionate feelings towards other people decline.

Scientific American

The other shoemaker gets his eyesight restored but he’s no better off than before. But because this earlier shoemaker lived in more prosperous times for shoemakers, I imagine he was still okay. This guy just needed to keep doing his own work and he was justly rewarded by simply selling his wares.

In all kinds of Elves and the Shoemaker stories, authenticity is rewarded. The word ‘authenticity’ comes from Greek authentes. This word has two related meanings:

- One who acts with authority

- Made by one’s own hands

Our cultures clearly revere people who make things with their own hands. Much folklore and fairy tale is about ‘being real’, and is related to a very common narrative trope about removing the mask to reveal your best life. It’s interesting, however, that people are buying the shoemaker’s shoes all the while thinking he’s made them himself. Normally this is exactly the kind of trickery that gets punished in stories! I propose the shoemaker gets away with this because good fortune happened upon him; he did not go seeking it out.

RESONANCE

A few centuries later Rhonda Byrne took the same ideology conveyed by the Grimms and ran with it. The Secret is a self-help book about the Law of Attraction and a huge bestseller.

Stories about elves, fairies and goblins were common in 20th century children’s literature, but they were the bowdlerised version, not the capricious slash evil hobgoblins of darker, earlier tales.

Modern young readers are likely to know about helpful elves due to Harry Potter even if they haven’t read a fairytale version. In Harry Potter House Elves take care of the needs of human wizards. They are also free of their obligation once given clothes.

FURTHER READING

I looked deep into the history of this story because I was interested in using the basic premise of this tale as a vehicle to say something different again, about generosity but also about whose labour we value and whose labour remains invisible (much like the elves are invisible). I called my revisioning “The Awlings“.