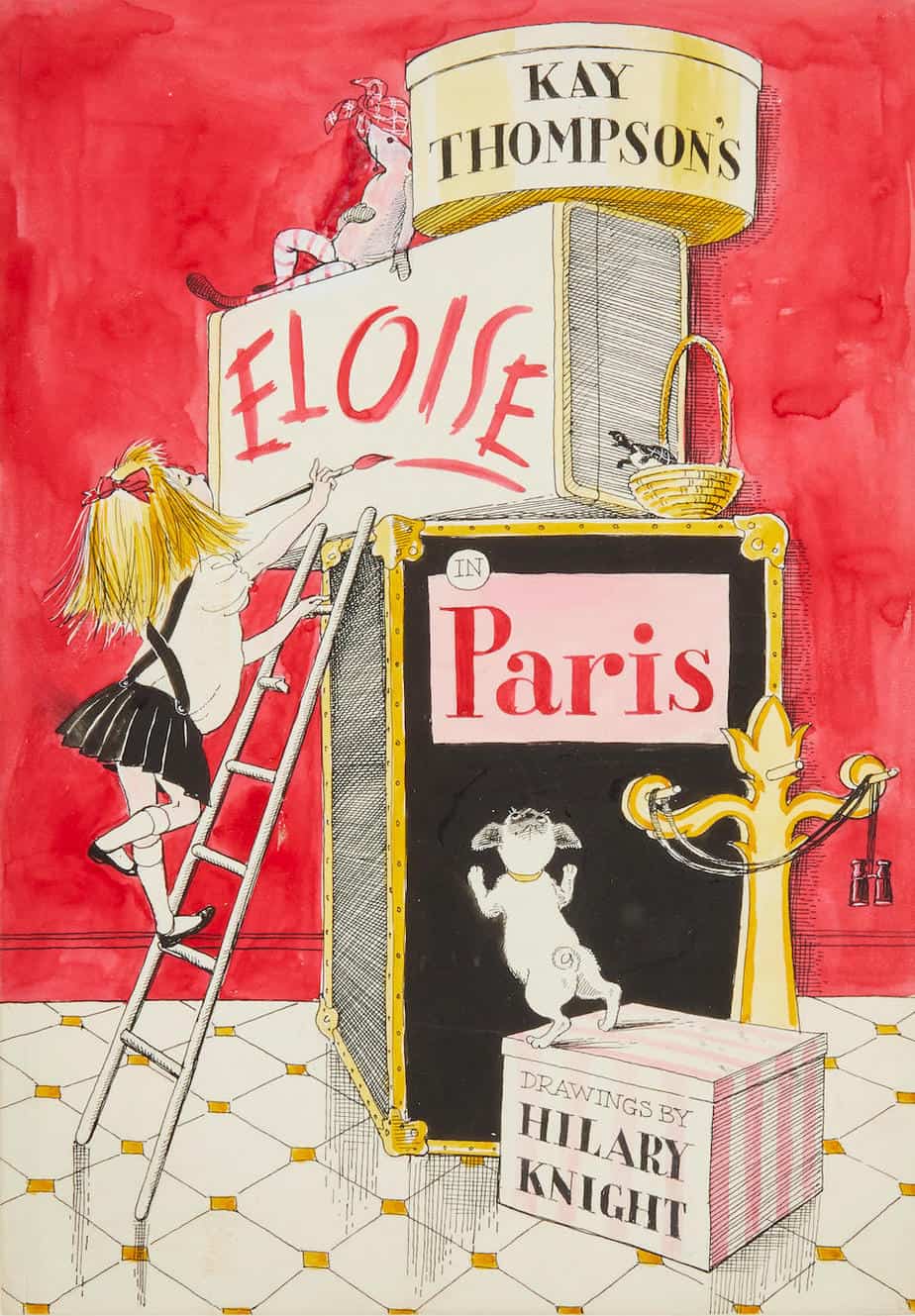

Eloise is a classic 1955 picture book written by Kay Thompson, illustrated by Hilary Knight. Writer Kay Thompson (1909–1998) was also a composer, musician, actress and singer. Illustrator Hilary Knight was born in Hempstead, Long Island, New York, in 1926.

Most popular picture books endure because they appeal to a dual audience of children and also to the adults who read it aloud, night after night after night. Eloise tips over into the ‘more for adults than for children’ category, telegraphed in the subtitle: A Book For Precocious Grown Ups. Since there is no such thing as a ‘precocious grown up’, this also prepares readers for irony.

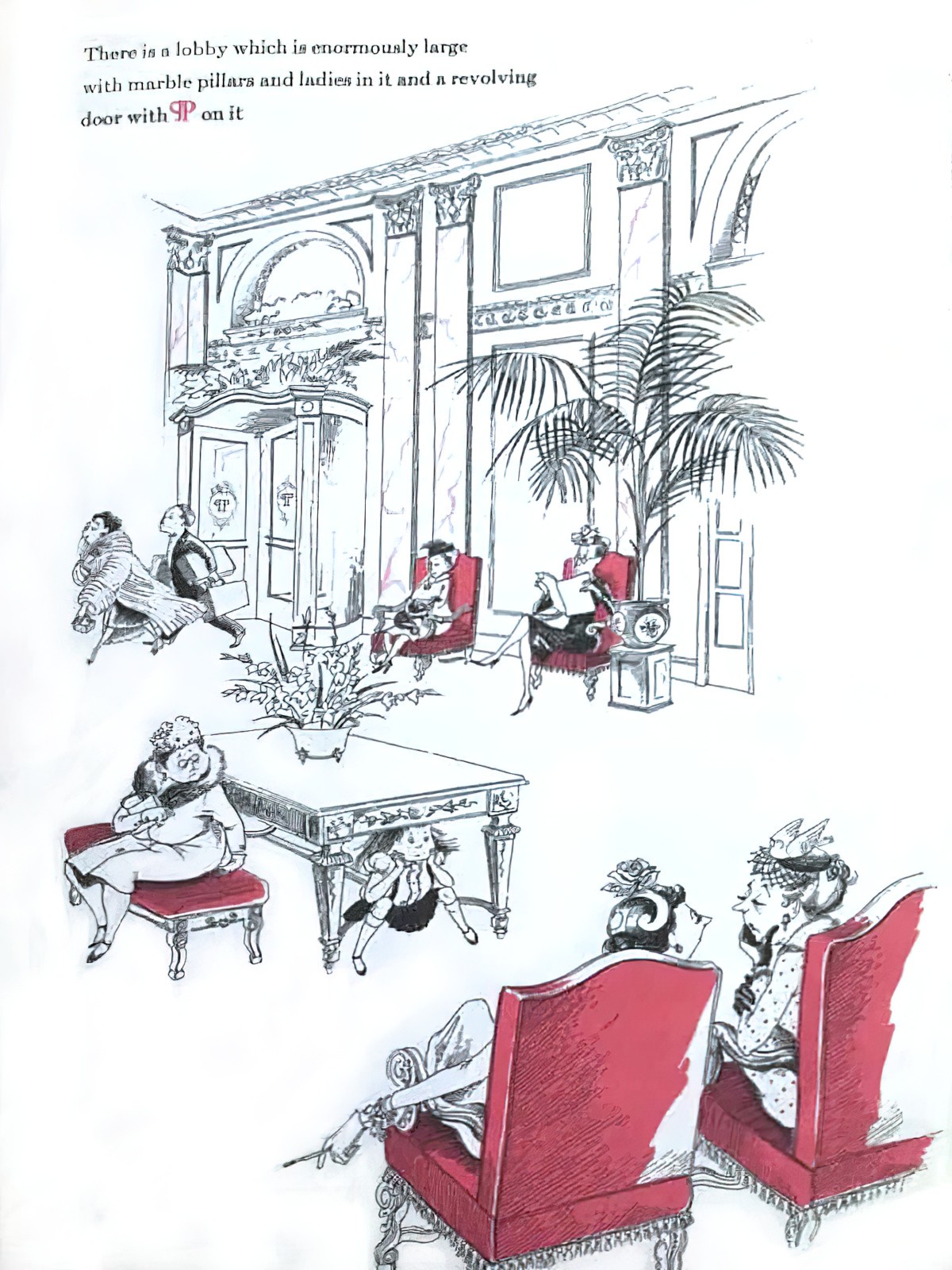

The main character is a six-year-old girl who lives in the top floor of an expensive New York hotel, cared for by her English nanny, called Nurse.

The nanny is an older woman who shows genuine affection for her charge, but she no longer has the energy to run around after a hyperactive child such as Eloise. So the care of Eloise is shared across the staff who work at the hotel and its environs. Eloise also inserts herself into the high-end experiences of paying customers, who look side-eyed at her. She sneaks into weddings and eats the food, opens packages not meant for her and has great fun ordering bizarre things via room service, instructing staff to ‘charge it’.

Eloise is much longer than a typical contemporary picture book, more suited to an adult’s attention span than a child’s, though I’m sure there are kids who love Eloise. In the early 2010s Lena Dunham became a prominent spokesperson for an Eloise revival. Eloise was her favourite childhood character. Lena grew up in New York herself, and identifies with the experience of living as a child in that very specific, very privileged social milieu. She has an Eloise tattoo. Dunham subsequently made a short documentary about the life of Eloise illustrator Hilary Kay after the illustrator heard about the tattoo and got in touch. The documentary is called It’s Me, Hilary: The Man Who Drew Eloise.

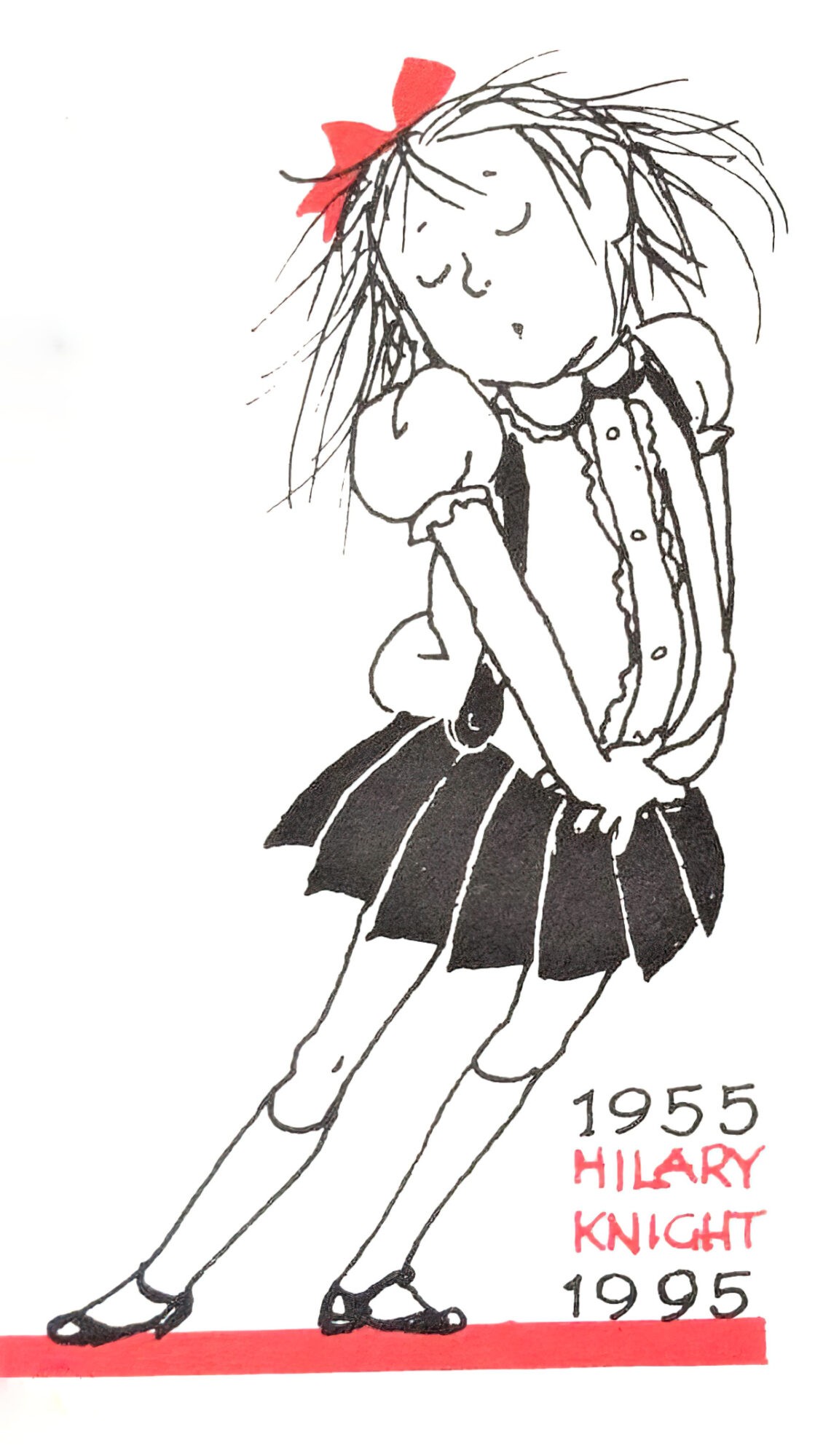

Looks like Eloise had a bit of a revival in the 1990s, with the publication of the complete collection:

IRONY

In Eloise, irony comes at us in many forms:

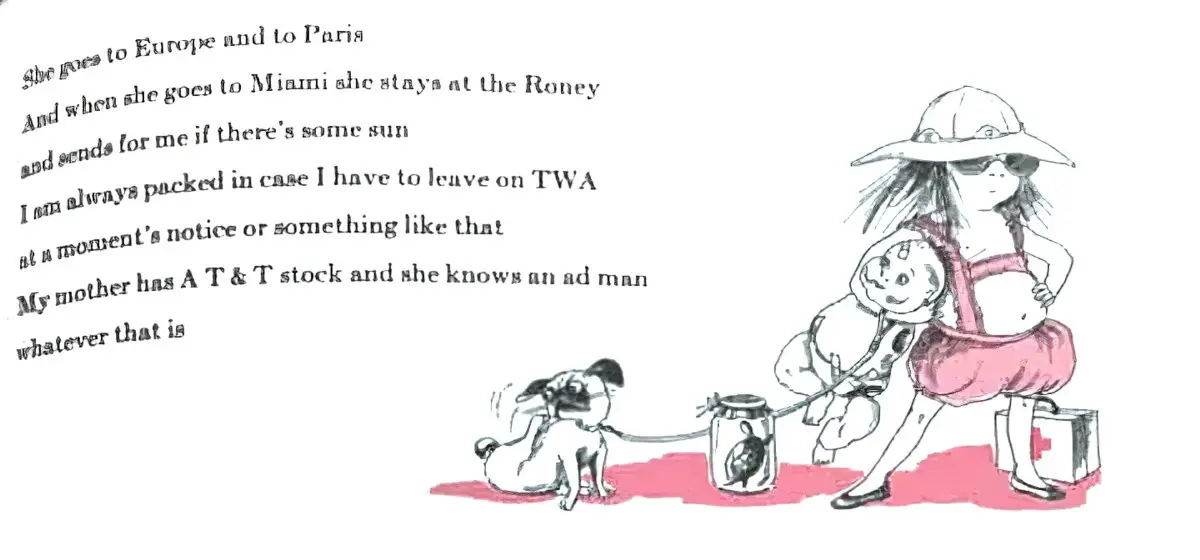

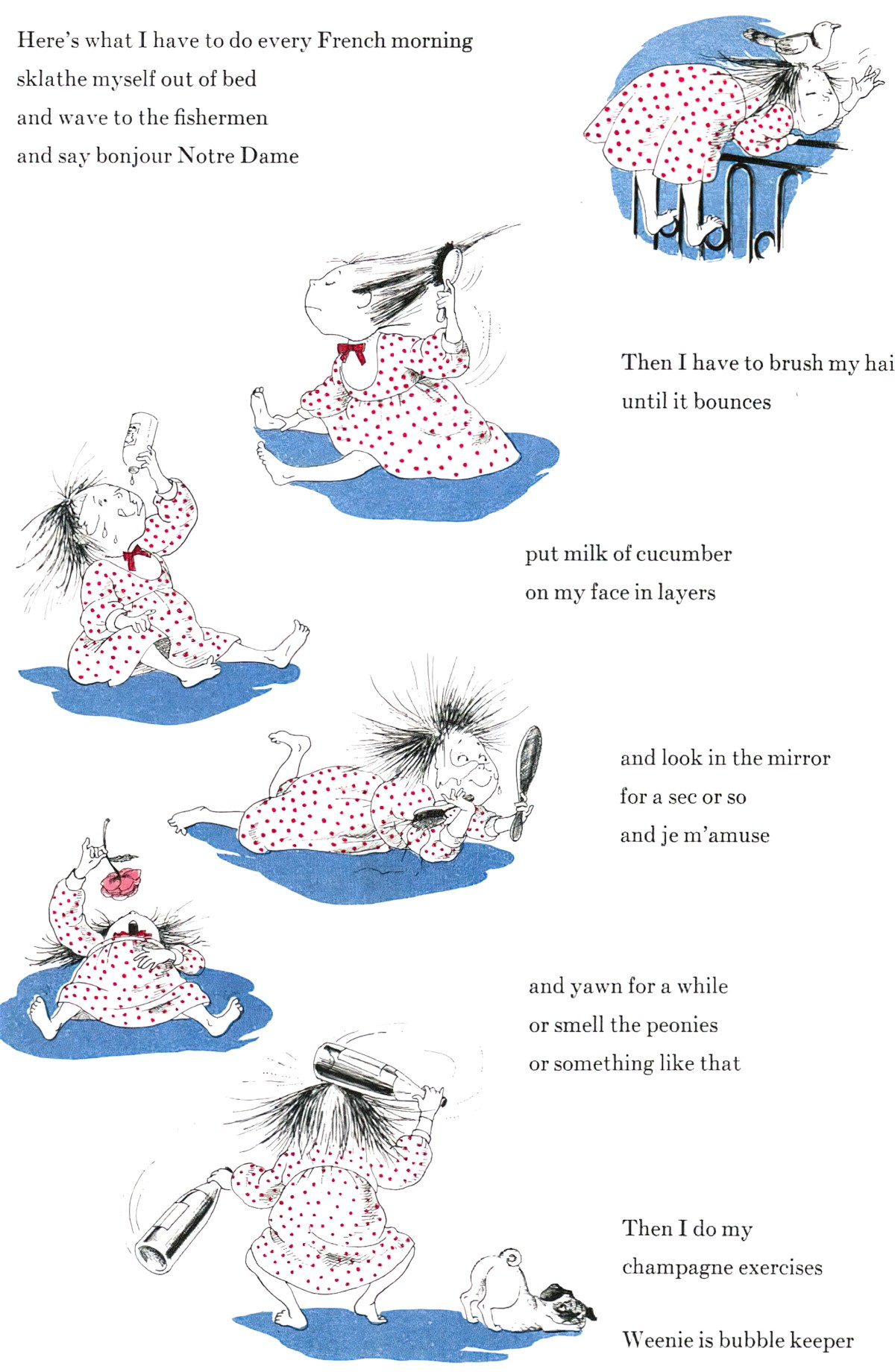

- The spectacle of a little girl living the life of a Dorothy Parker character

- Gender non-conformity

- The gap between how the adult reader understands a situation (Eloise is unwelcome) compared to how Eloise perceives a situation (she is entitled to do what she wants, whenever she wants)

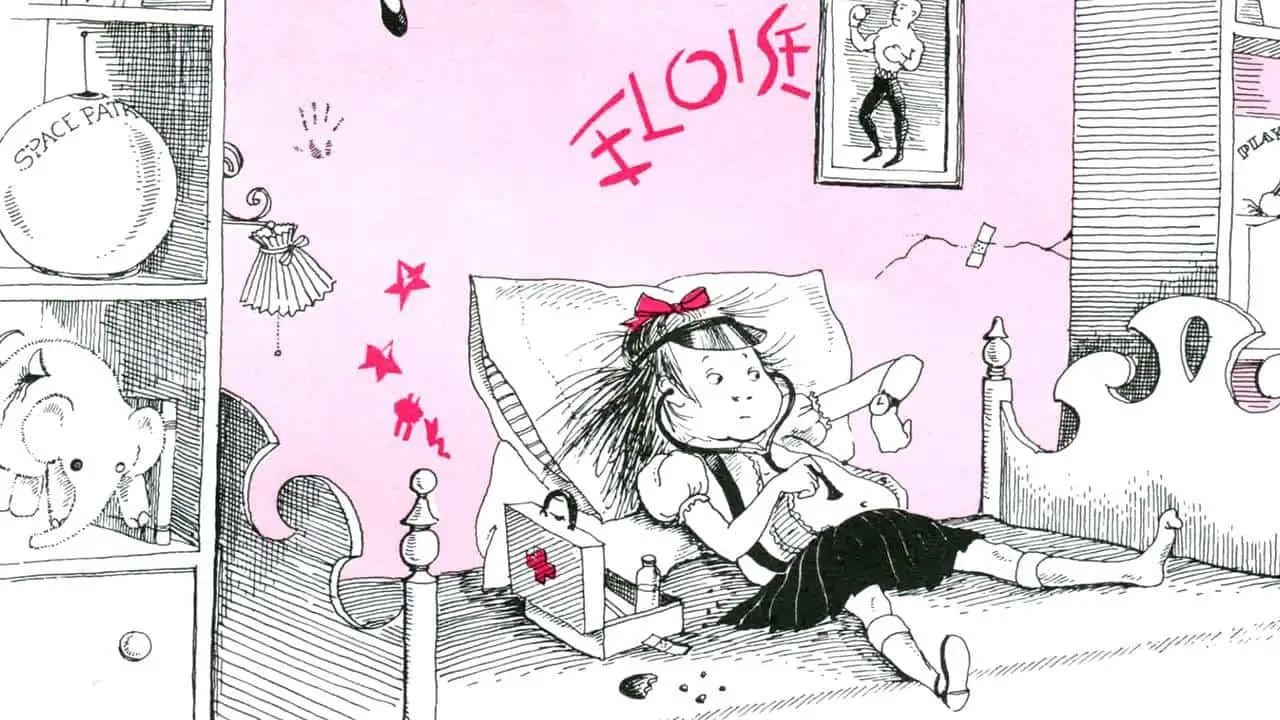

- Related to that, the gap between reality and fantasy, which the reader understands but Eloise doesn’t (tortoises don’t wear sneakers, though Eloise tells us hers does). Hilary Knight uses a different colour line drawing (mostly red) to show us when characters exist only in Eloise’s imagination.

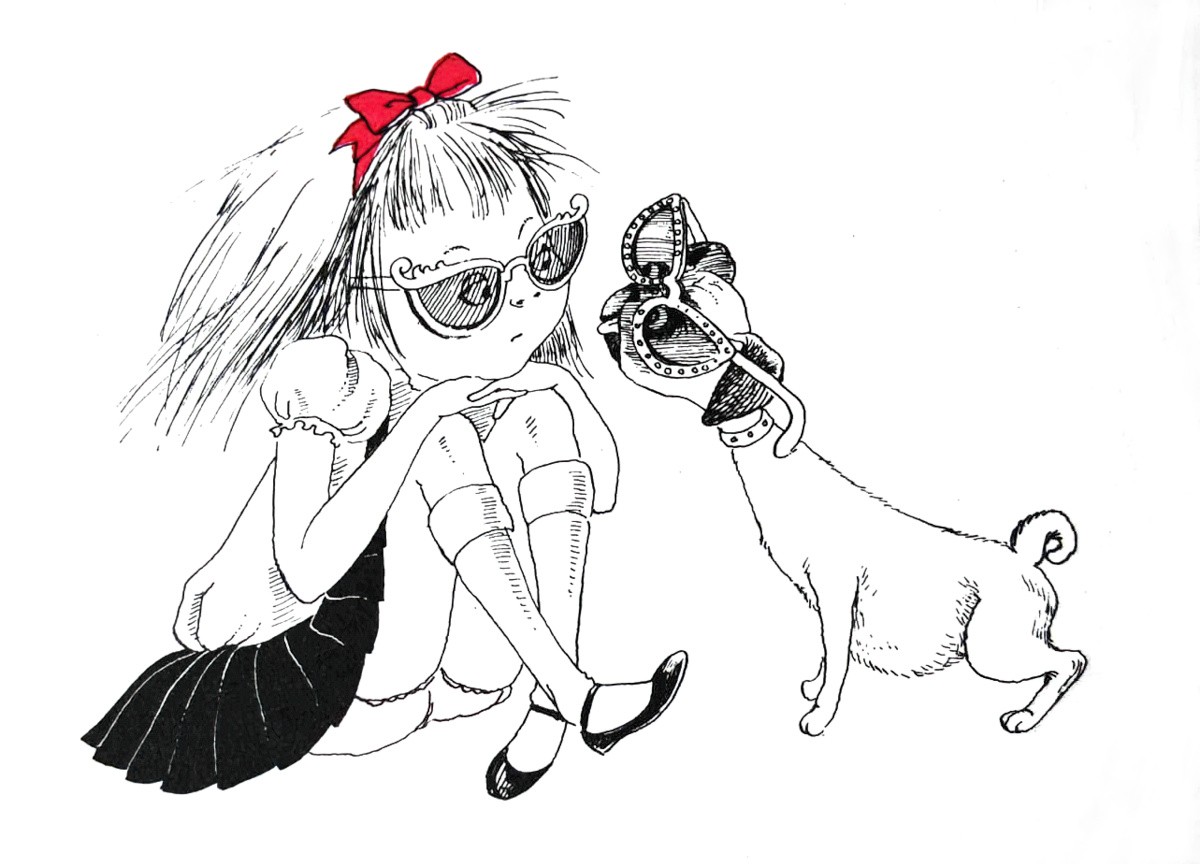

- ‘Hat on a dog’ humour e.g. sunglasses on the dog (this is readily understood by child readers)

CHARACTERISATION

This theme song for Eloise tells you a lot about the character.

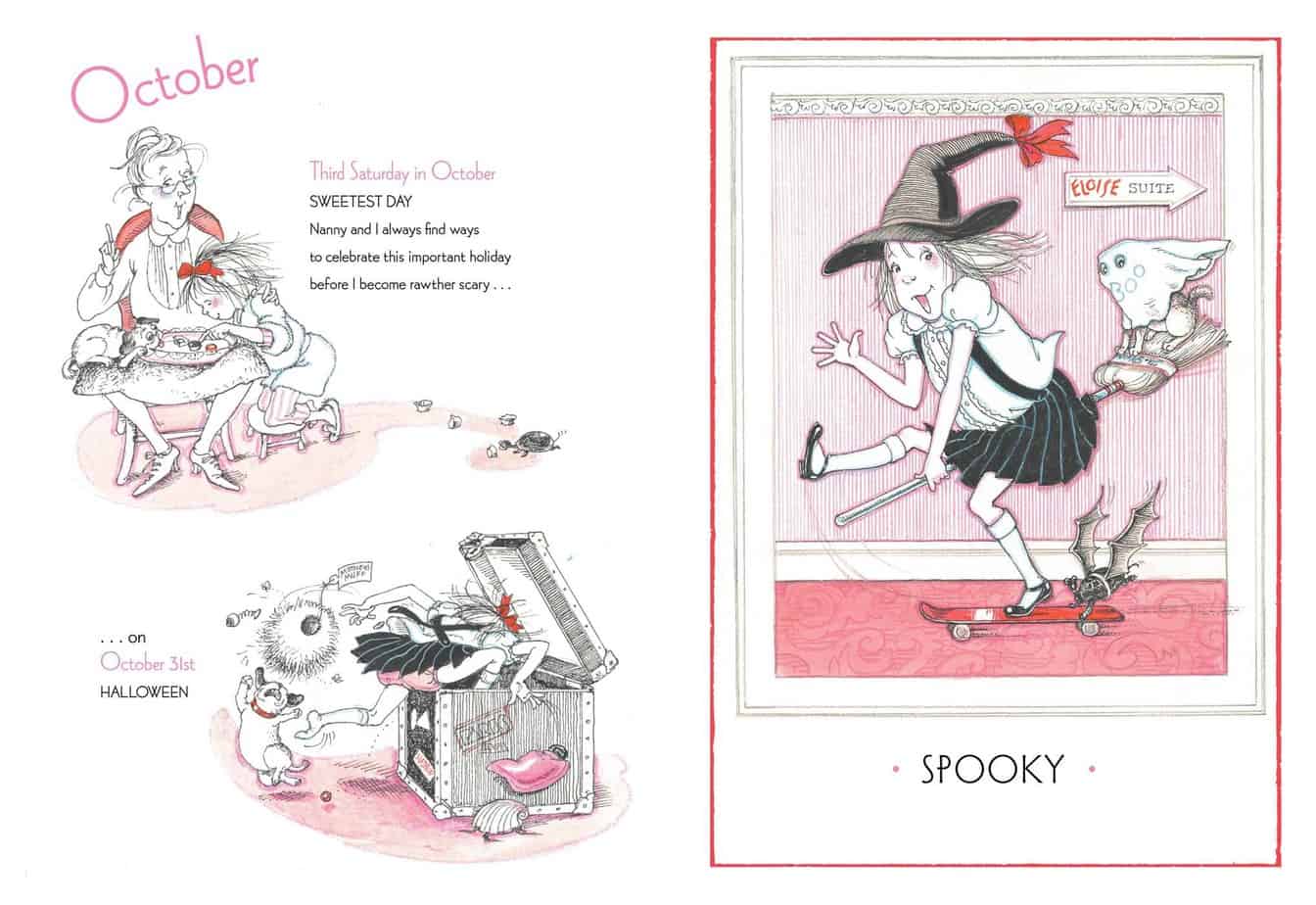

WITCH ARCHETYPES

I have written previously about the burlesque witch archetype. You’ll recognise them from cartoons which emphasis the grotesqueness of ageing in a woman’s body, and celebrate the freedom which comes once a woman shucks off all expectations to conform to gender (to look pretty and act ladylike). Burlesque witches tuck their saggy boobs into their belts, drink copious amounts of wine and laugh raucously in the company of likeminded woman friends.

Eloise is a burlesque witch in a child’s body. But I feel a little sad for Eloise, because unlike those older women, Eloise has no likeminded friends. The life of this little kid is ultimately one of loneliness.

The adults put up with Eloise because they have their own jobs to do and don’t need an inquisitive kid getting in their way. The mother is contactable only via the phone, charged ‘long distance’. The father is never mentioned. Filling in the gaps, I would guess Eloise is the ‘love child’ of a woman from an uber-wealthy family. The family is paying to house Eloise away in a gilded cage, assuaging their own guilt of abandonment by letting her charge whatever she wants to their account.

Nurse is another witch archetype. Eloise tells us she wears ‘bones in her hair’, which is a far more (delightfully) grotesque way of saying her hair clips are made of ivory. This makes the woman sound like Baba Yaga. Eloise shares with us private information she knows about Nurse, which reminds me of how trans women are so often depicted in fiction. By telling us about Nurse’s ‘very big girdle’, the emphasis is on transformation from grotesque (read: non-feminine) to socially acceptable. Via the childlike narration of Eloise, the story suggests a daily masking and unmasking happens with older women, as if one version of Nurse is authentic (crone), and the girdled version a poor facsimile of glamour.

Nurse wears a kimono (or what Westerners call a kimono) which has the furisode sleeves. Furisode are worn only until marriage. I’m not convinced this cultural knowledge transfers to this New York context, but may be signalling that Nurse is unmarried. (I’d assumed she’s unmarried anyway.) The unmarried older woman is frequently seen as a pathetic figure because proper womanhood requires birthing one’s own children (and looking after those children yourself).

The carnivalesque plot and voice of this book overturns all rules of femininity, such as ‘women must get married’, starting with Eloise, who rejects all rules of girlhood.

THE NAUGHTY CHILD IN PICTURE BOOKS

Adults can identify with wanting to muck up when required to work and be sensible. Ignoring social rules without consequence is a universal fantasy across ages. Children’s books about naughty children are especially popular with children, though a significant proportion of adult gatekeepers of children’s literature don’t appreciate bad behaviour when it’s left unpunished, thinking fictional children are bad role models for real child readers.

This affects which ‘Naughty Children’ books take off and endure. Many have a cult following and the best stay in print, dipping in and out of popularity. Eloise is an example of that. Punishment as acceptable parenting practice is out of fashion, of course. It seems to me that if you’re trying to get a picture book published today, ‘naughty children’ are okay so long as there’s emotional honesty (a la Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day). First person narration is a safer choice for that.

THE INFLUENCE OF ELOISE ON CONTEMPORARY PICTURE BOOKS

AN AUTHENTICALLY CHILDLIKE VOICE

Judith Viorst broke new ground when she wrote Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day. She wrote from the heart about the difficult emotions experienced in a typical, childhood day, without varnishing. She utilised a few techniques perfectly suited to emotional honesty, and there, I feel, came from Eloise:

For one thing, Viorst launched straight into the singulative part of Alexander’s story, chopping off the iterative section at the start. Neither Kay Thompson nor Judith Viorst dispense with iterative information entirely, though. Any information about the general, everyday (iterative) part of the child character’s life comes at us haphazardly, as if issued unedited from a child.

‘As if issued unedited from a child’ is another way of saying both authors make use of psycho narration.

WORD PLAY

In many ways, despite her immense wealth, Eloise is the Every Child. All children use language creatively when learning to speak. All children need to move their bodies, a lot.

But speaking from parenting experience, if you have a child like Eloise, get her tested for AD/HD and dyslexia. Seriously. The labels may (or may not) help secure accommodations when she is required to conform in a school environment. Applicable labels will certainly help her to explain herself to herself.

By the way, dyslexia is more than ‘getting letters back to front’. Dyslexia on the same gene as AD/HD, so AD/HD and dyslexia frequently go hand-in-hand. These genes are also related to autism, which in girls especially, often means children seek out adult company, spend a lot of time imagining scenarios, and when young, lack the theory of mind to know which people are ‘real’ friends.

As for the fictional character of Eloise, her strange vocabulary can be explained by the reality that she sneaks around adult environments all the time, and adults speak differently to each other than to children. “Oh my Lord!” is Eloise’s catch phrase. We can deduce that adults frequently say this whenever they see Eloise coming.

In some ways, the Fancy Nancy series is a grand-daughter of Eloise, who creates her own neologisms. “Let’s skibble down to the lobby!”

I have previously said that spirited girls such as Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby, or Sara Pennypacker and Marla Frazee’s Clementine are the grandchildren of Anne of Green Gables. We might throw Eloise into that mix, though the link between Anne Shirley and Eloise is not immediately obvious due to their very different economic circumstances. However, they are both highly imaginative, love words, and are cared for most in the world by a perfectly adequate older woman who is not her birth mother.

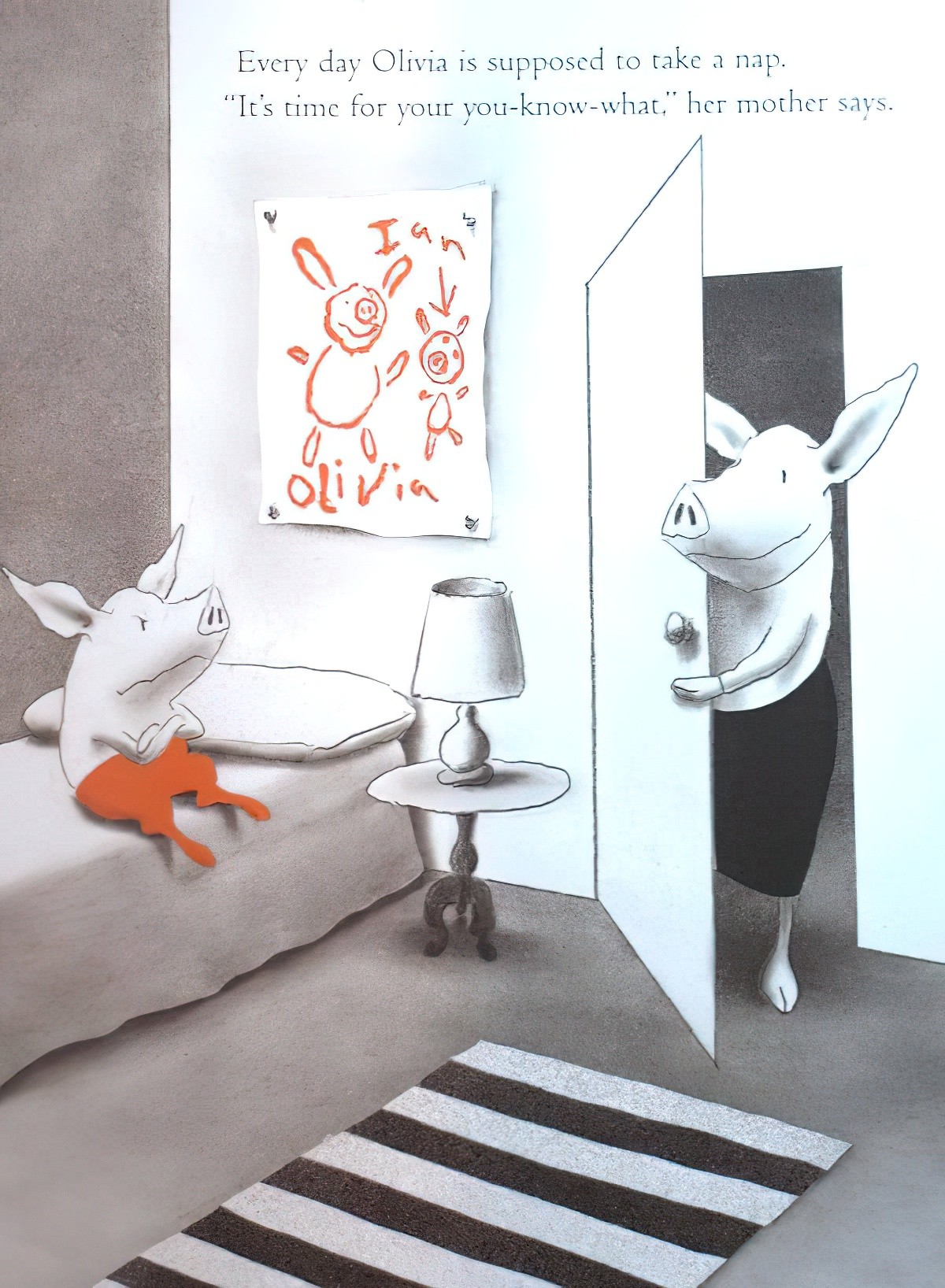

ELOISE AND OLIVIA the karen pig

The influence of Eloise on Ian Falconer’s Olivia is clear, from the brattiness to the New York setting to the use of accent colour. Personally, Olivia the Pig shits me to tears, but I have no problem with Eloise, who I find funny. It would be a useful exercise for me to work out why, exactly, that is. I suspect a number of factors are at play:

- The first person psycho narration of Eloise really helps because I’m in awe of how well the author has emulated a childlike voice. Olivia is written in third person, which inserts an unseen adult narrator. So much of the humour is lost. (Also, if there’s an adult here, why isn’t that adult telling her to stop being such an insufferable brat?)

- Perhaps it also helps that I feel a little sorry for Eloise, who has been abandoned by her parents. Olivia seems to have two loving parents and I don’t feel the slightest bit bad for her.

- Olivia’s parents are creating a monster. Find your own damn toy. While I’ve no doubt that Eloise grew up to be an insufferable adult, I imagine adult Eloise as a burlesque witch, whereas Olivia will simply be a Karen. (She’s a pig because pigs are pink, which makes Olivia white.)

- The Olivia books go out of their way to be message-y, like ‘Girls can do boy things too!’ whereas Eloise was unashamedly for adults, and so the creators were free to do what the hell they wanted with their child creation.

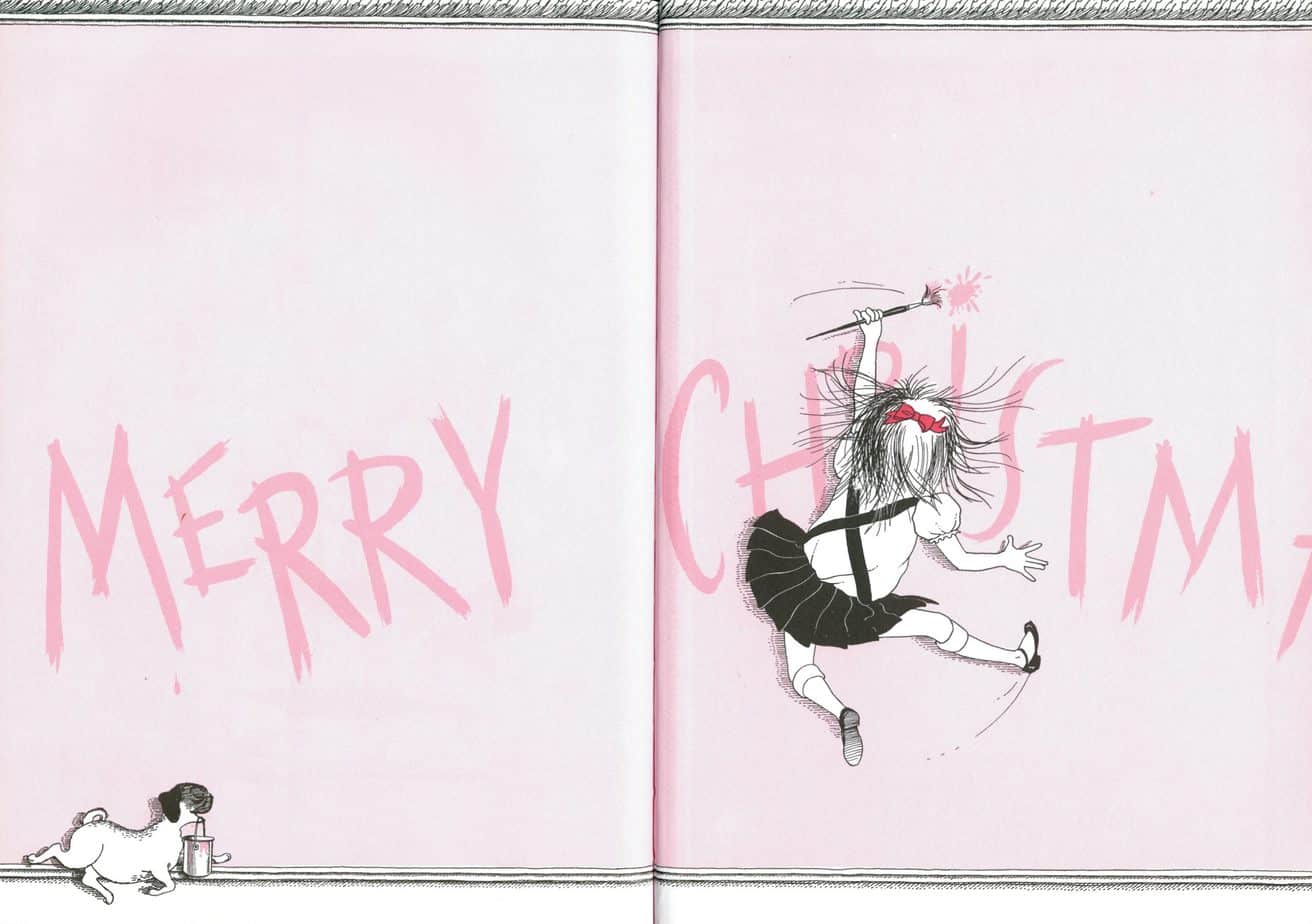

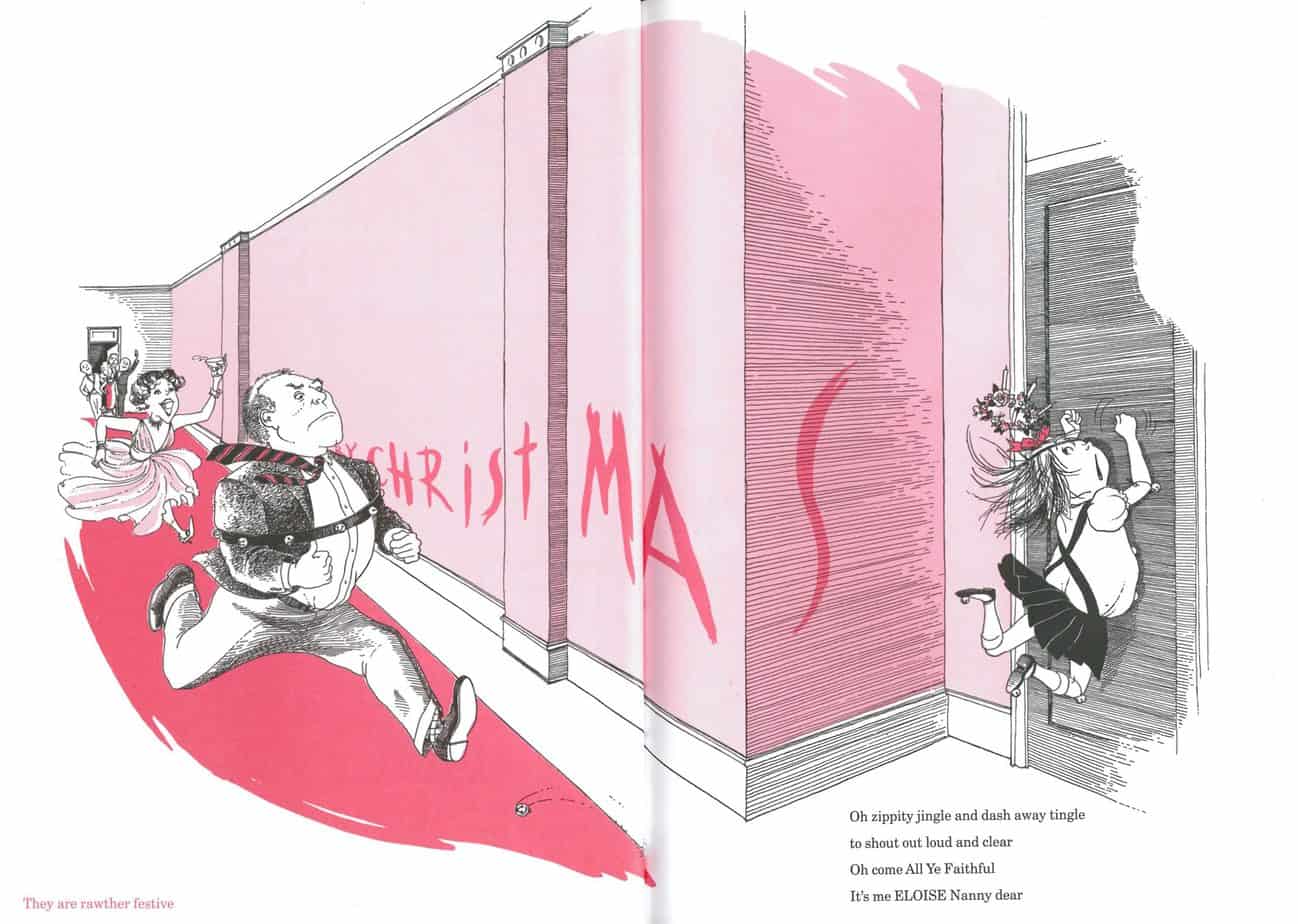

ELOISE AT CHRISTMASTIME

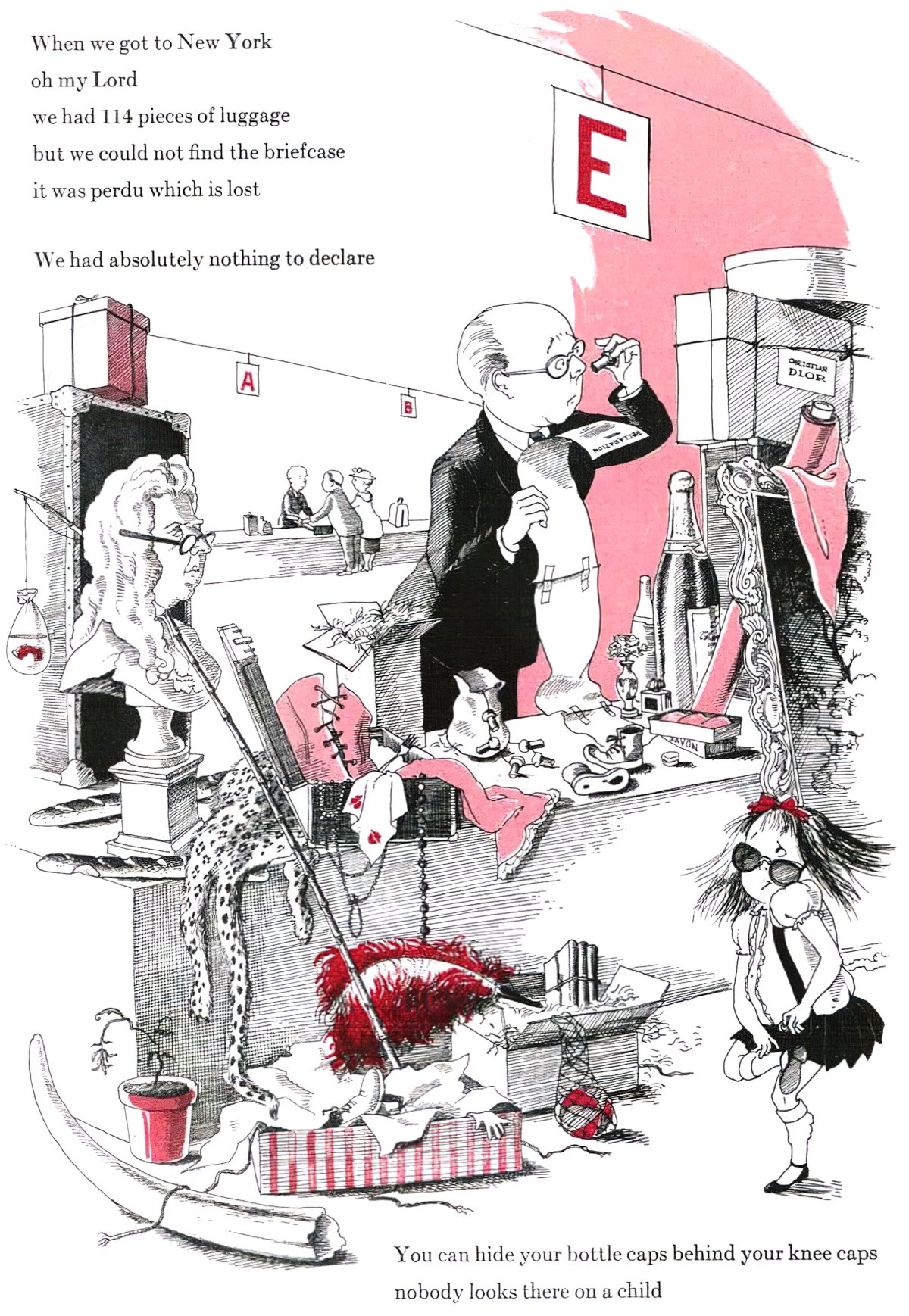

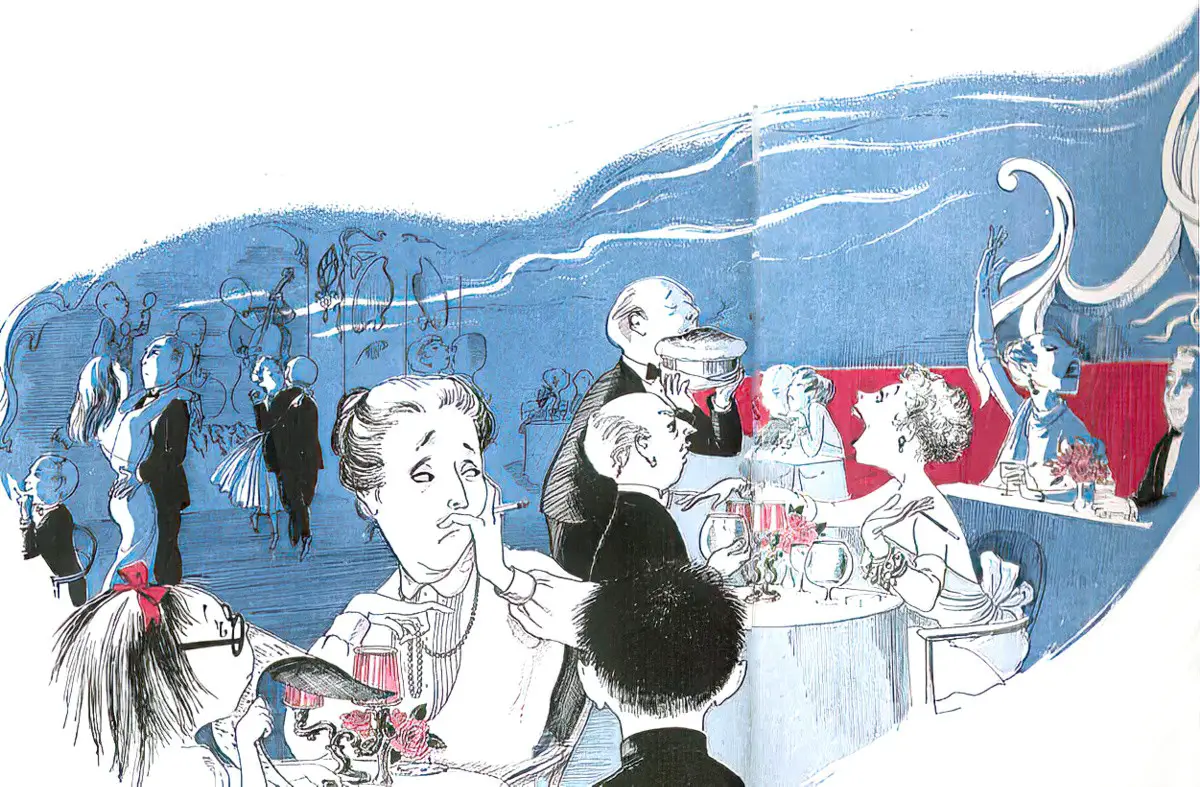

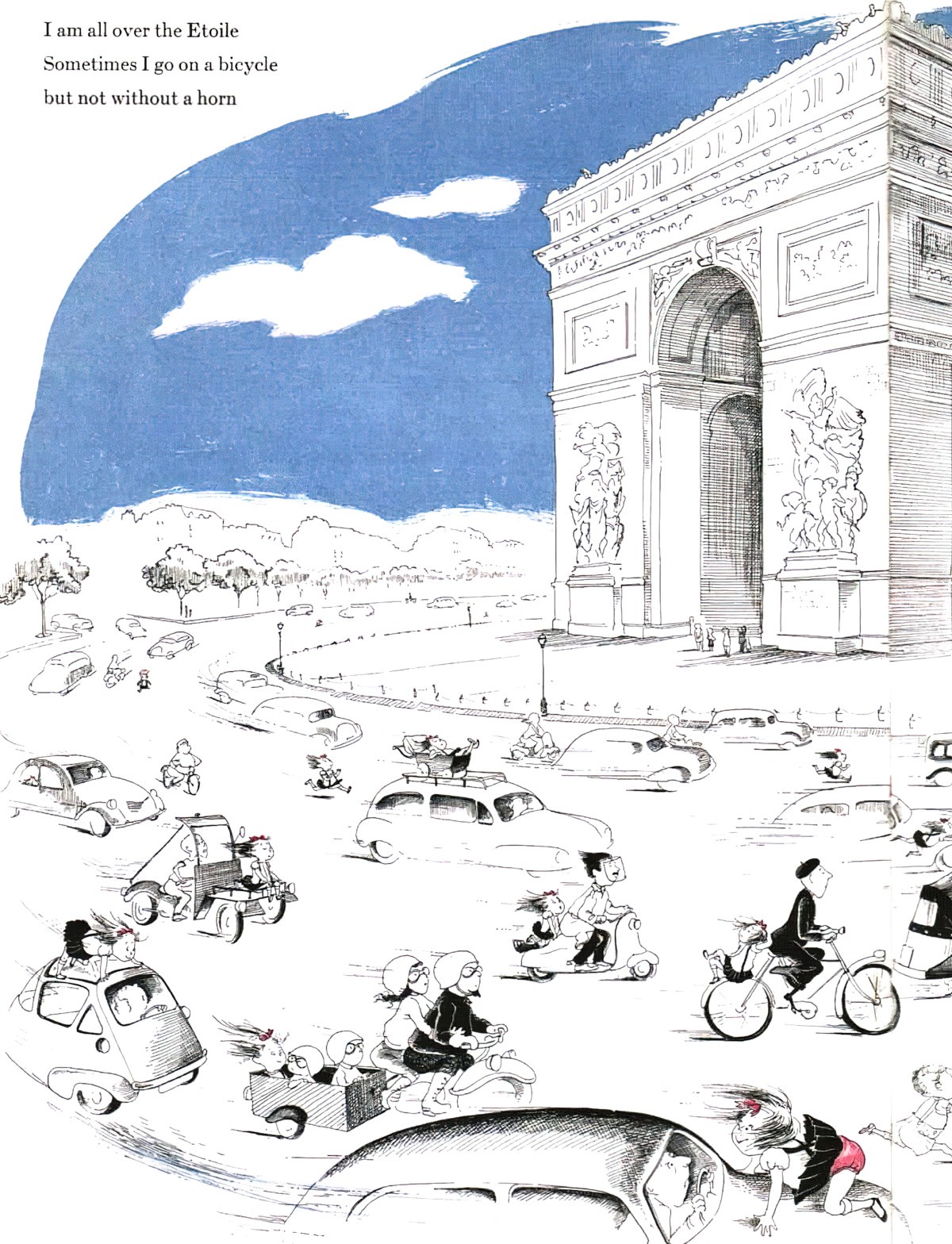

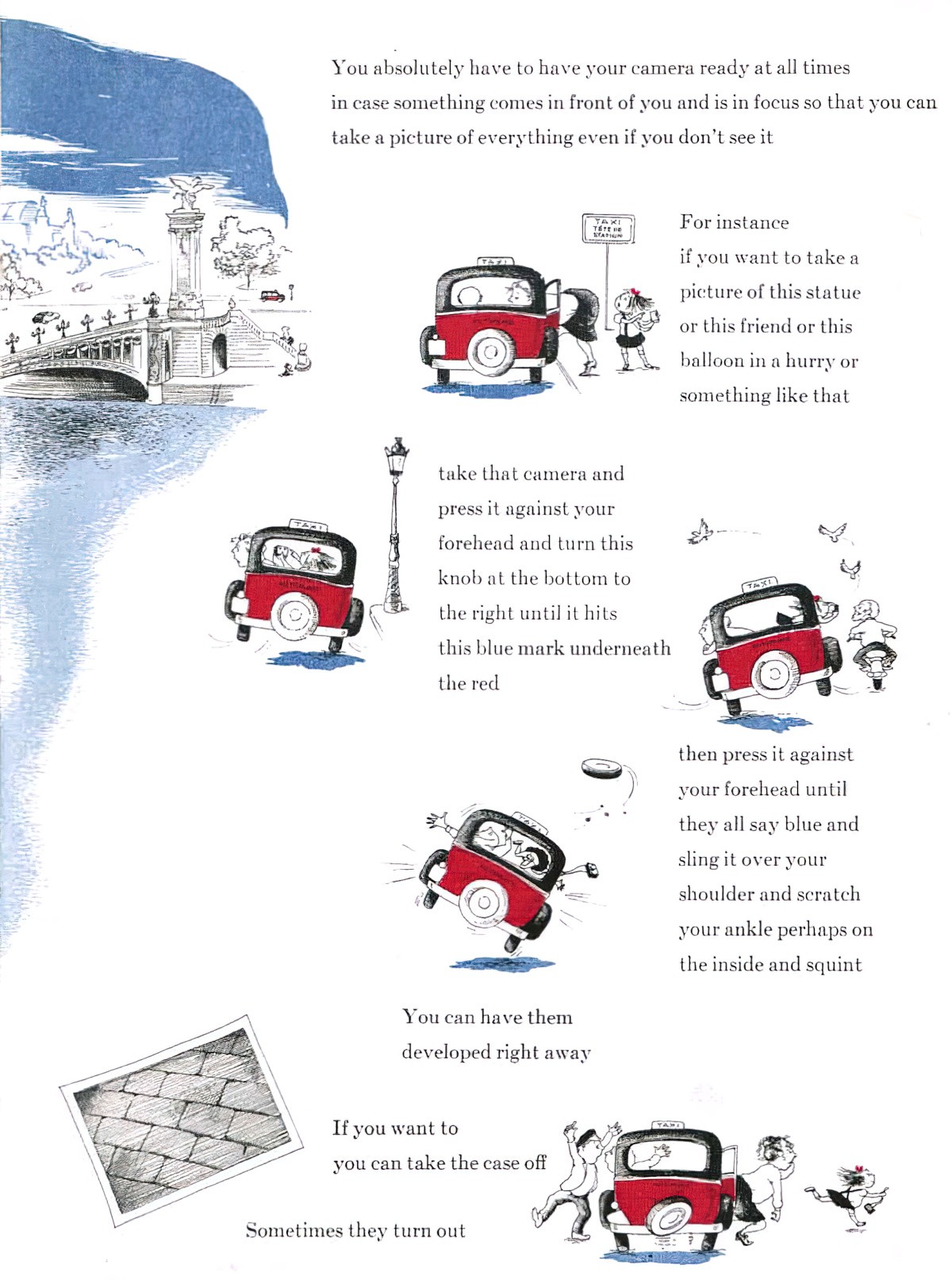

ELOISE IN PARIS (1958)

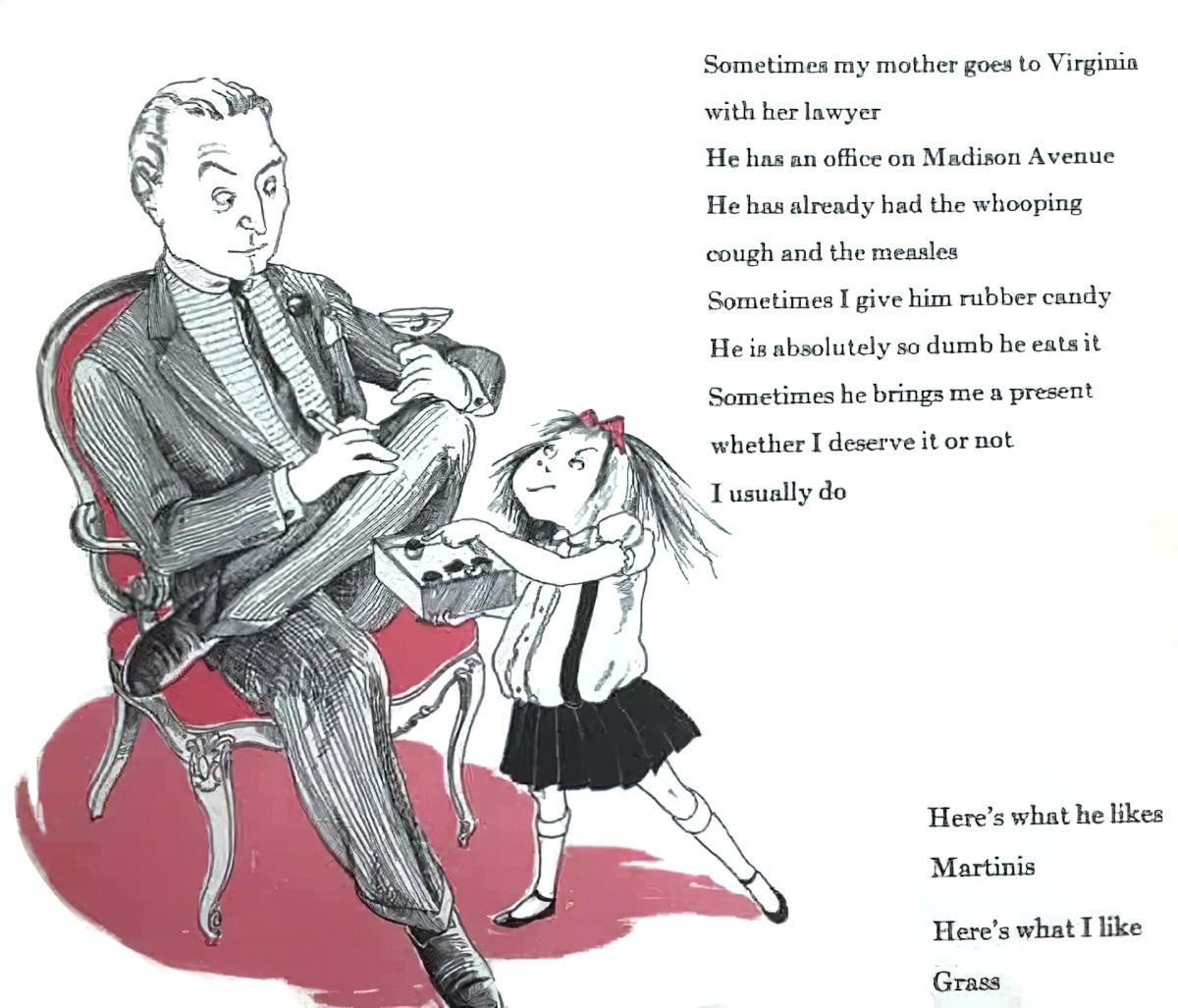

Although Eloise would be happy with ‘grass’, she holidays to expensive cities, where once again, she is a fish-out-of-water as a child in expensive restaurants etc.

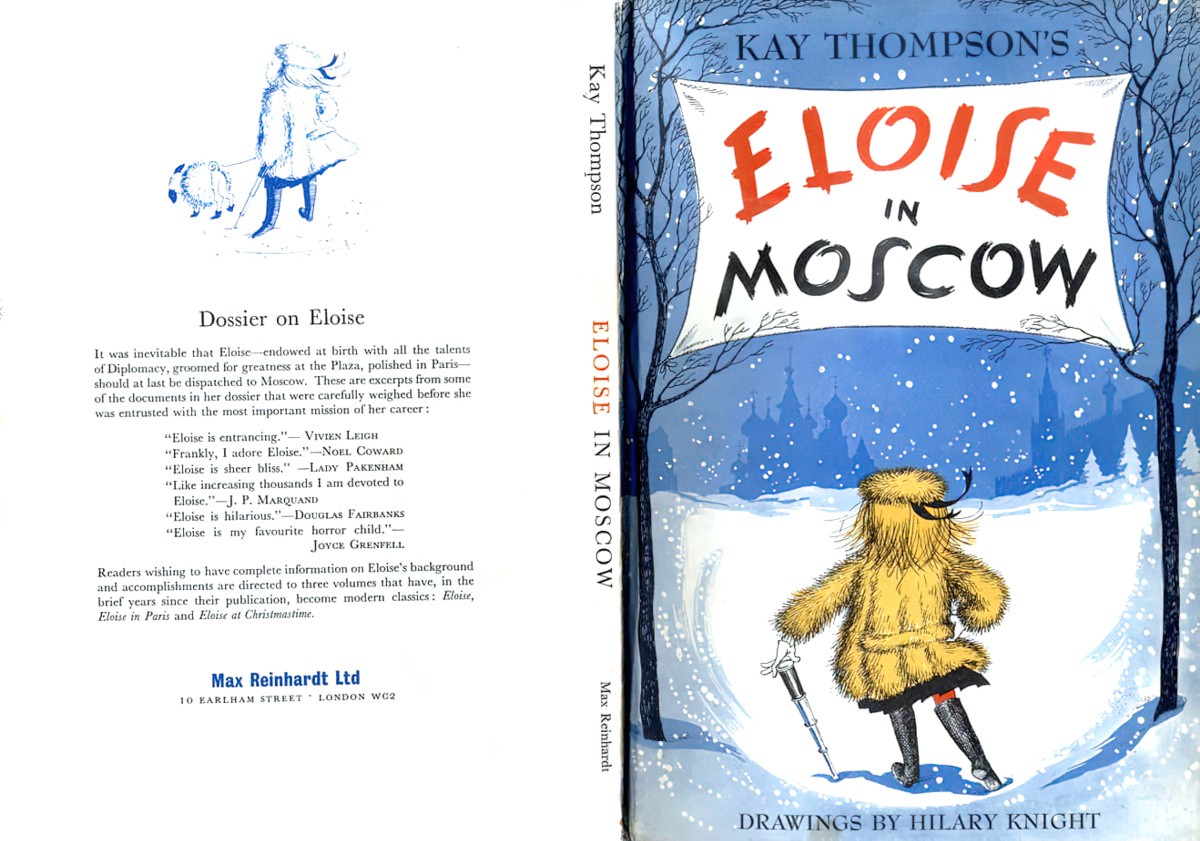

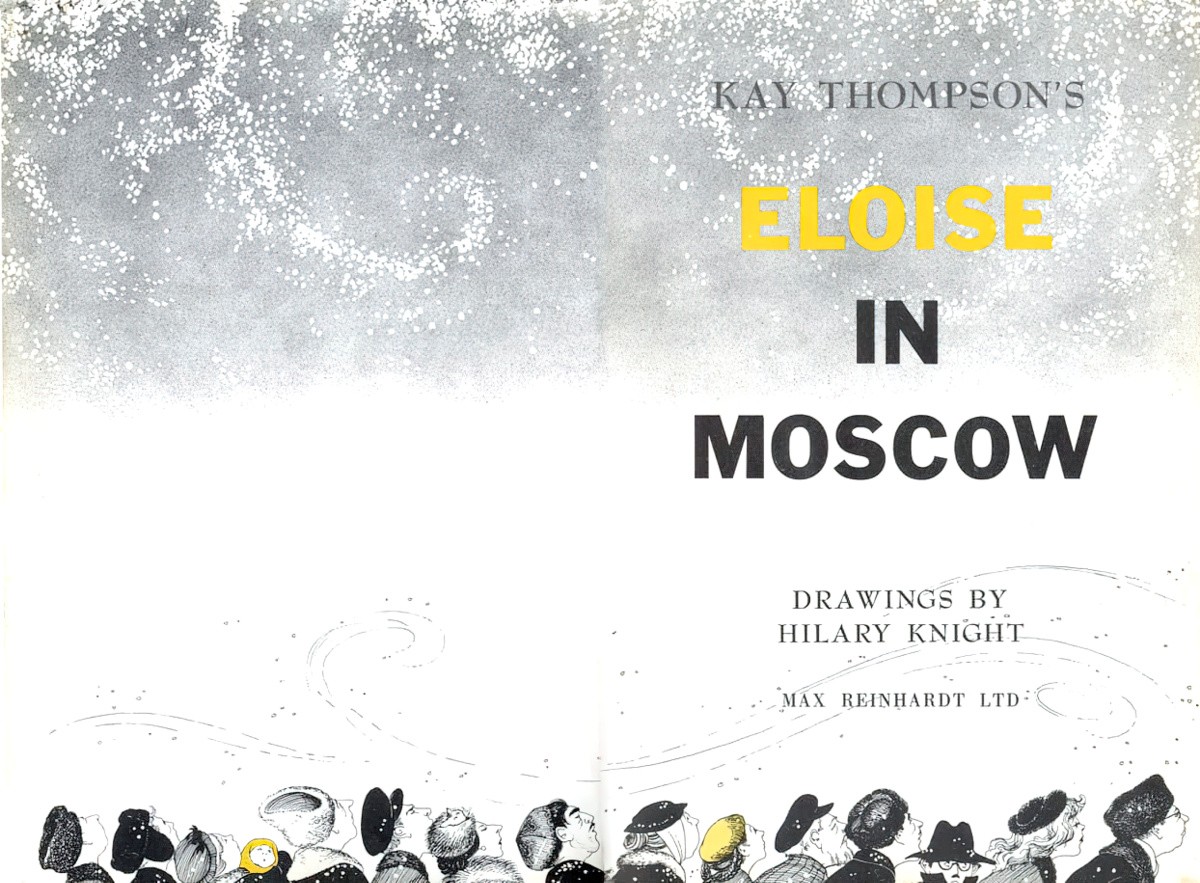

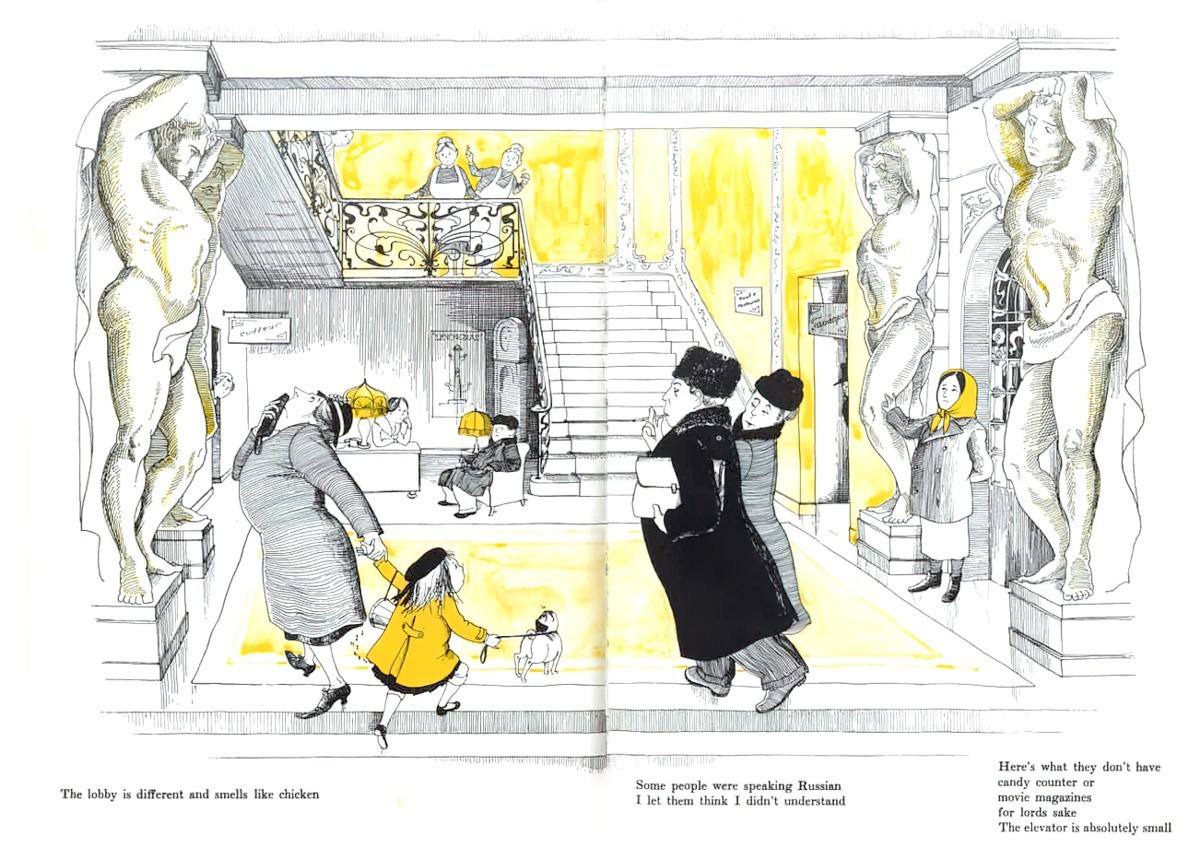

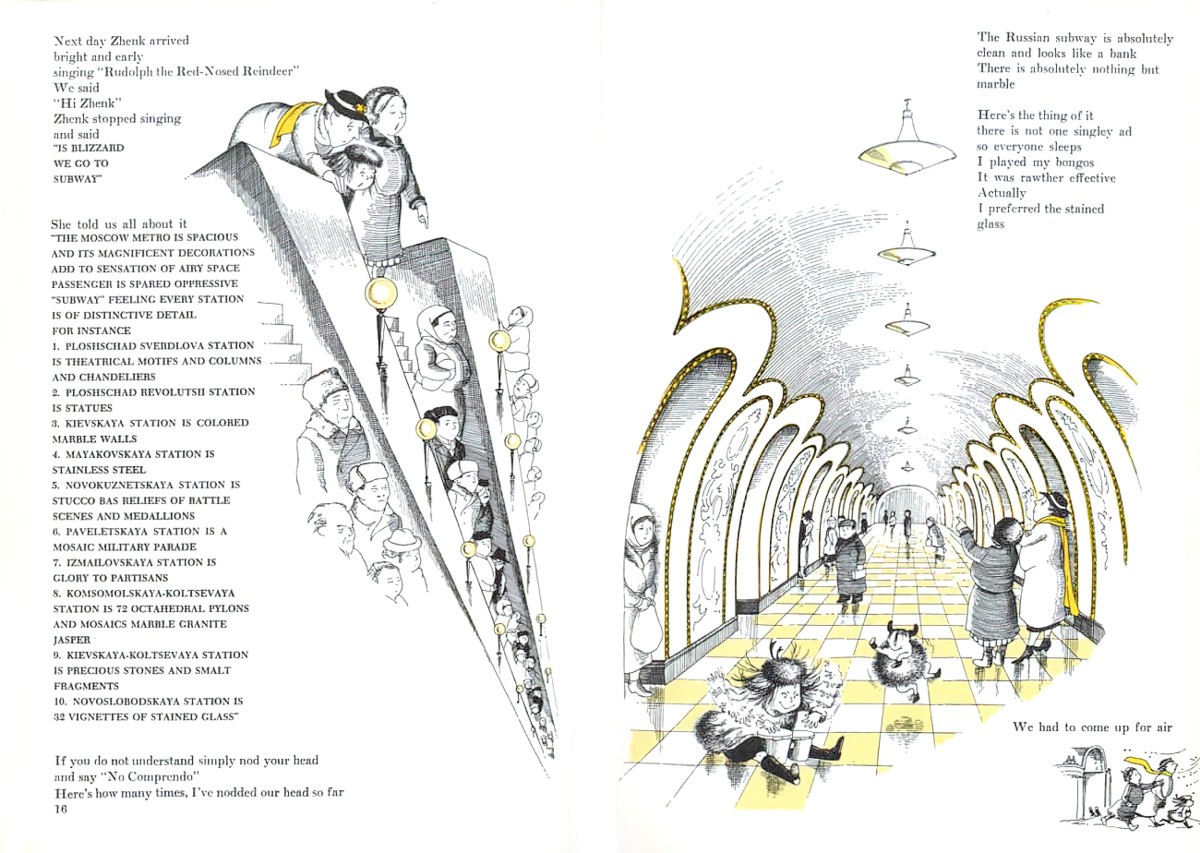

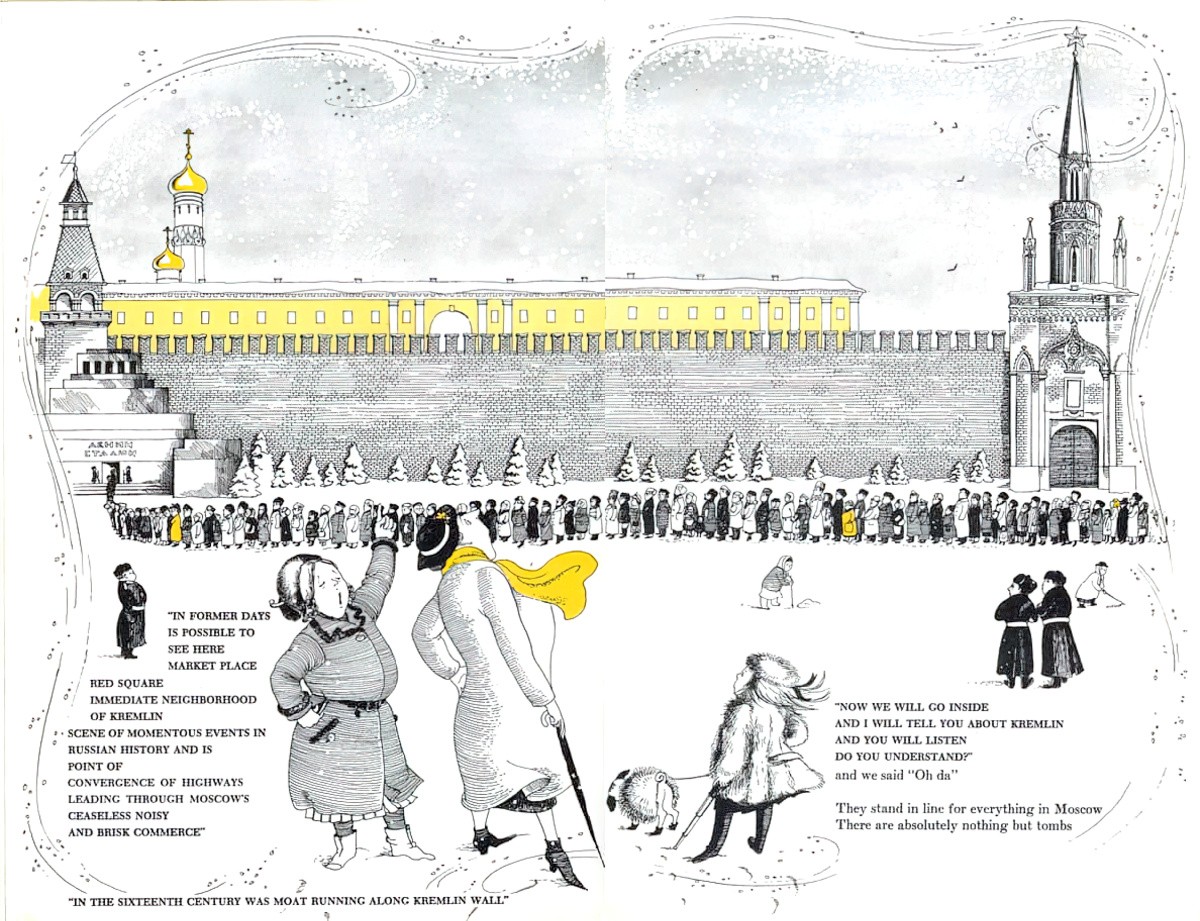

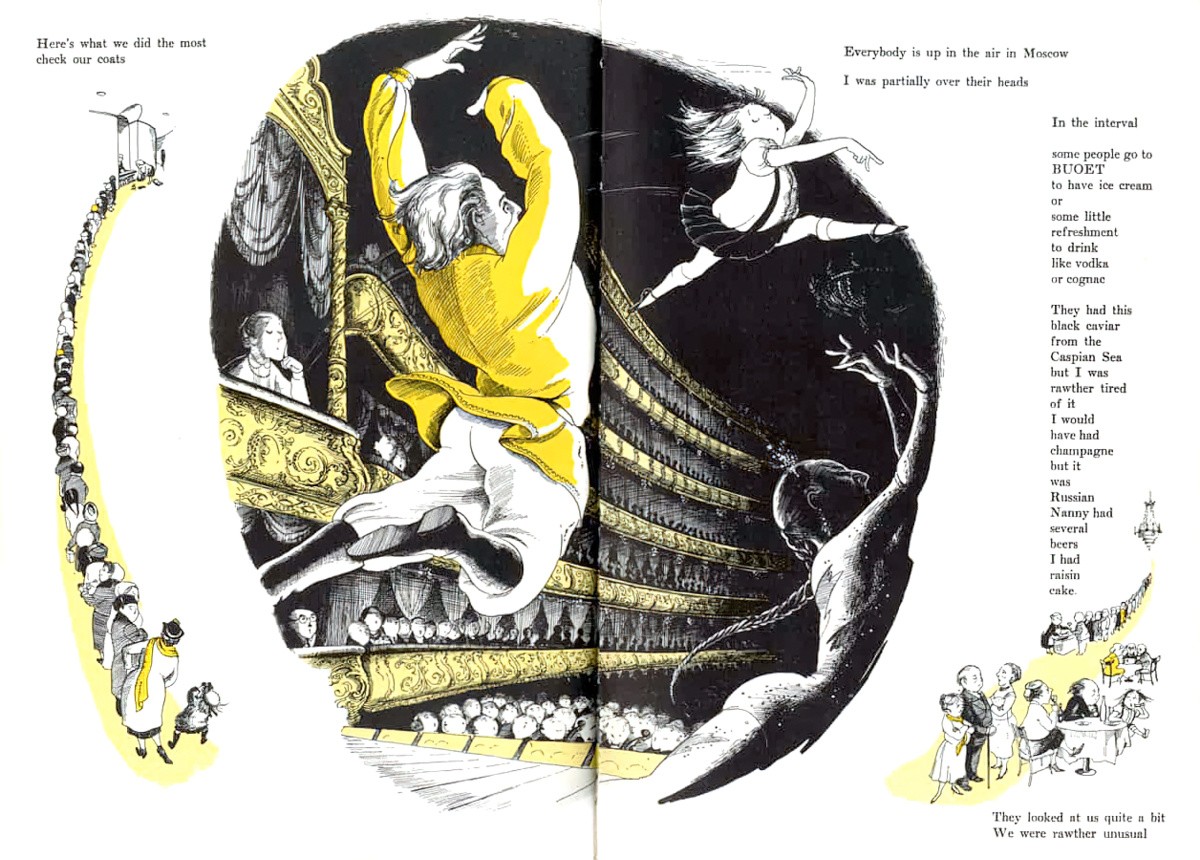

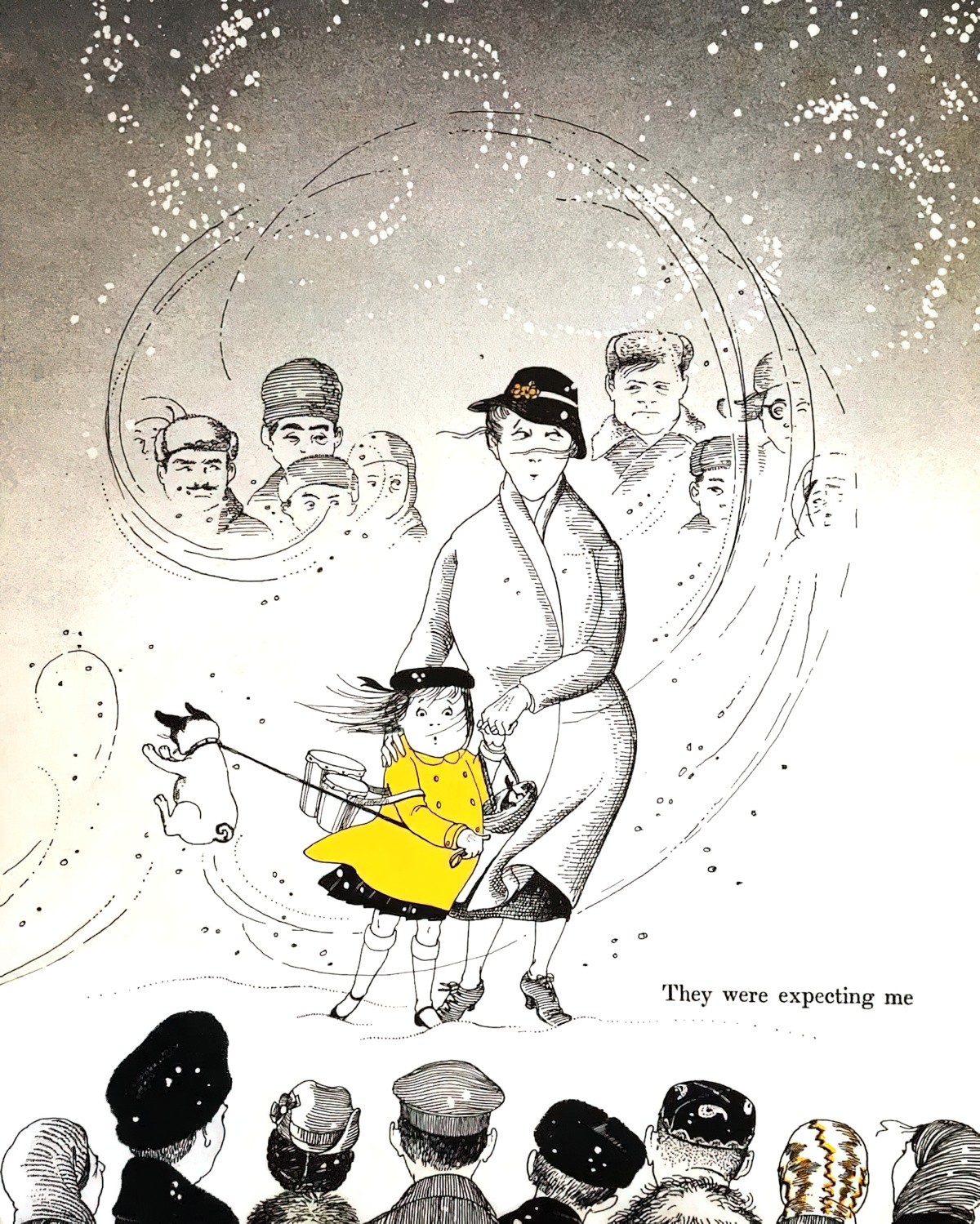

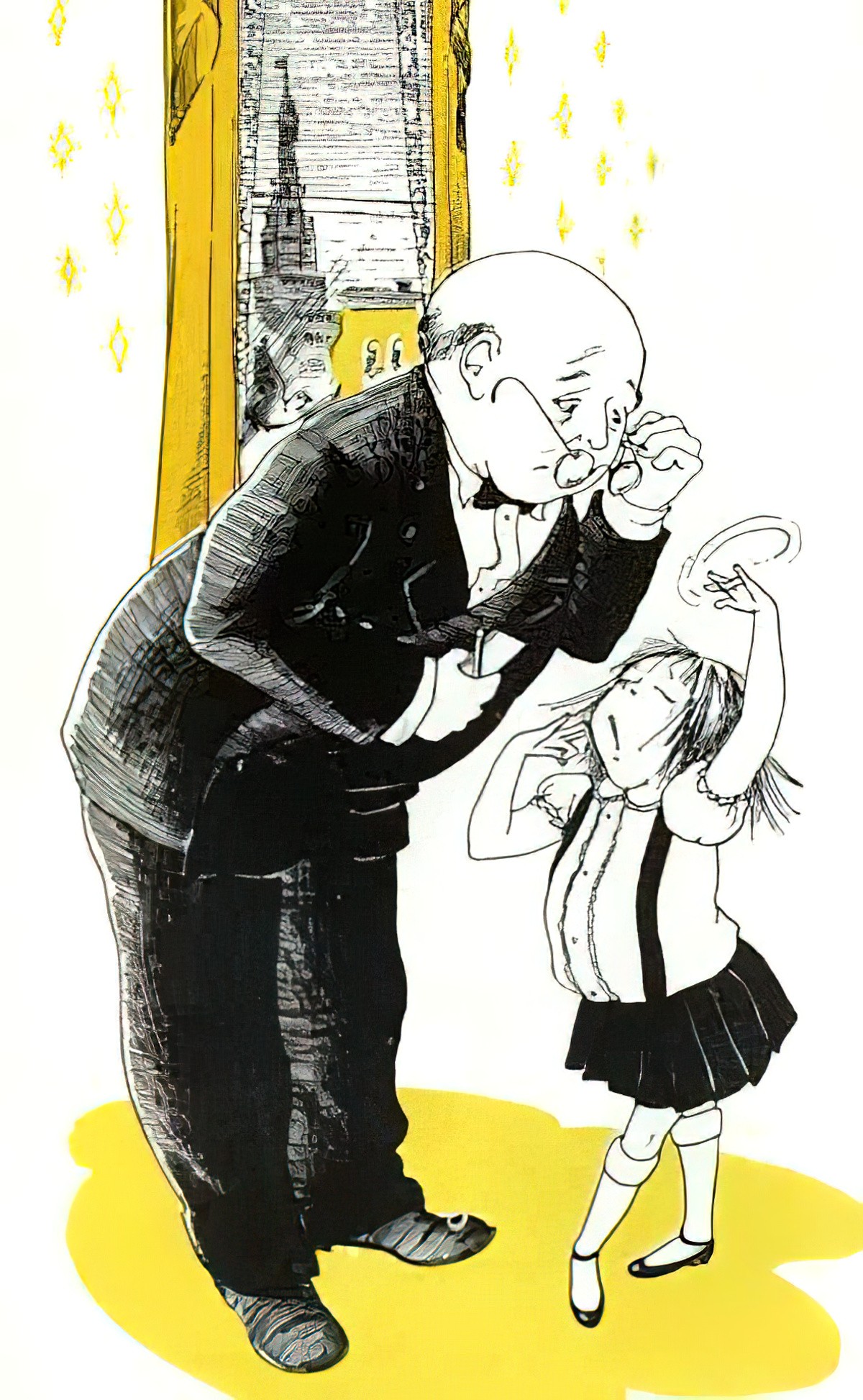

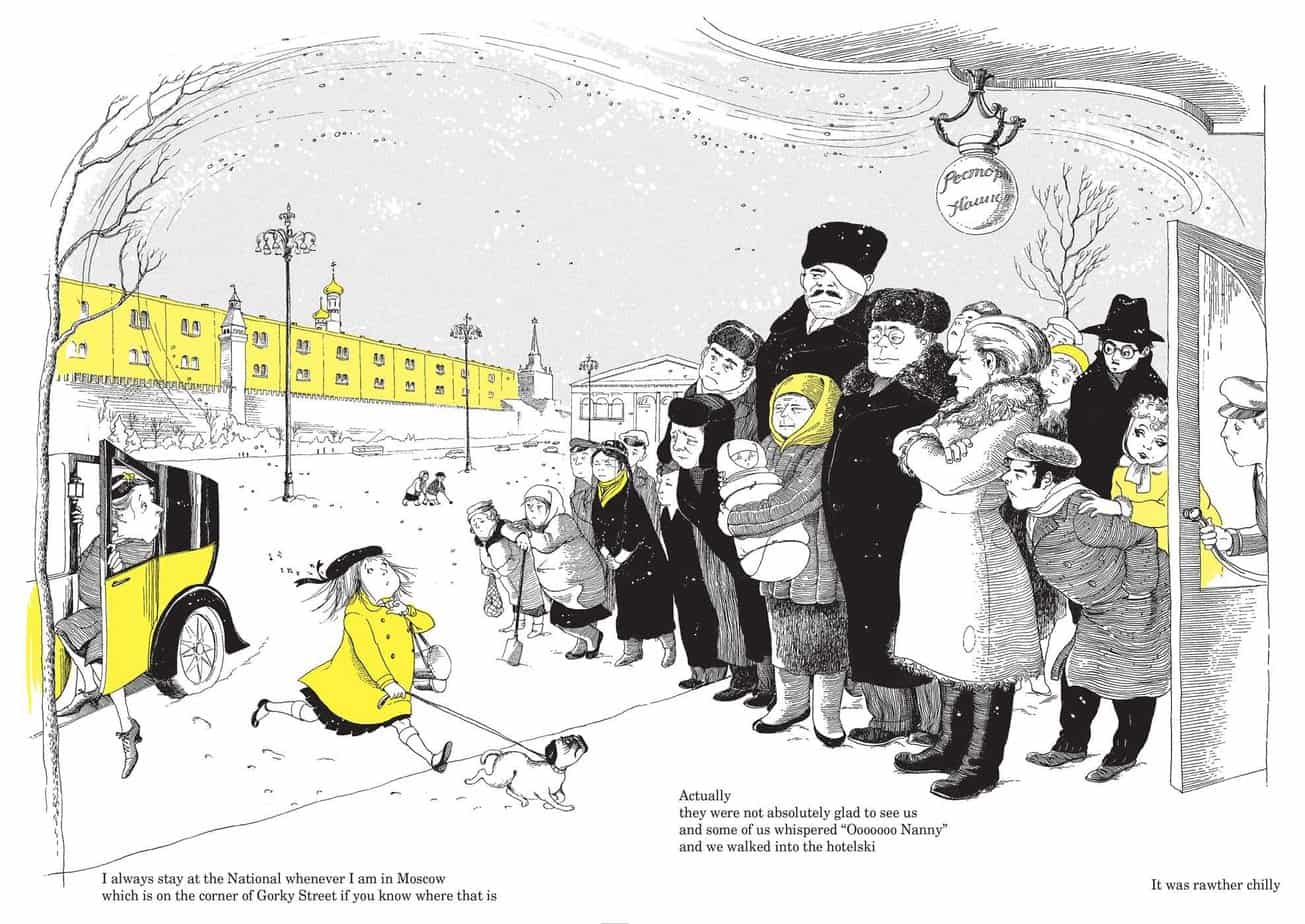

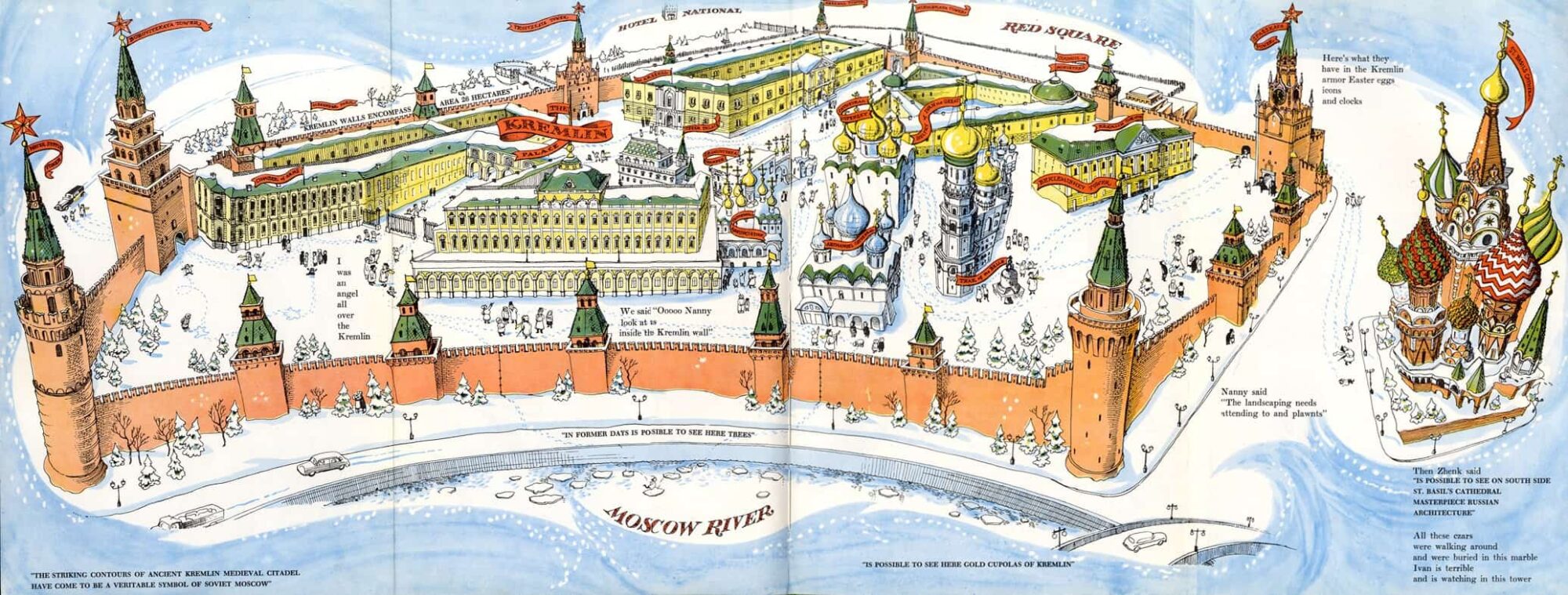

ELOISE IN MOSCOW (1959)

The first Eloise made use of pink as accent colour. Pink is more closely associated with expected femininity than it was in the mid 1950s, otherwise I might say the girly pink colour was meant to be ironic.

When Eloise visits Moscow, the accent colour is yellow.

ELOISE ADAPTED FOR ACTUAL KIDS

I say ‘adapted’ mindfully. We might also say ‘bowdlerised’. The beginner readers, published around half a century later, lose something when aimed at kids.

I can’t tell the extent to which Hilary Knight did his own illustrations for these readers (credit is shared) but I don’t like how Eloise is looking at the camera, breaking the fourth wall. In the 1955 edition, Eloise is in her own world, and that is the point. Once she invites the child reader to look at her, she’s no longer alone, but she also becomes an object, less in control of her own story, charged with the task of performing for her unseen audience. Though I’m sure she’d love the attention, and the opportunity to show-off, objectification would teach her, before childhood is over, that girls’ bodies are for looking at. Just as well Eloise will never grow up, eh?

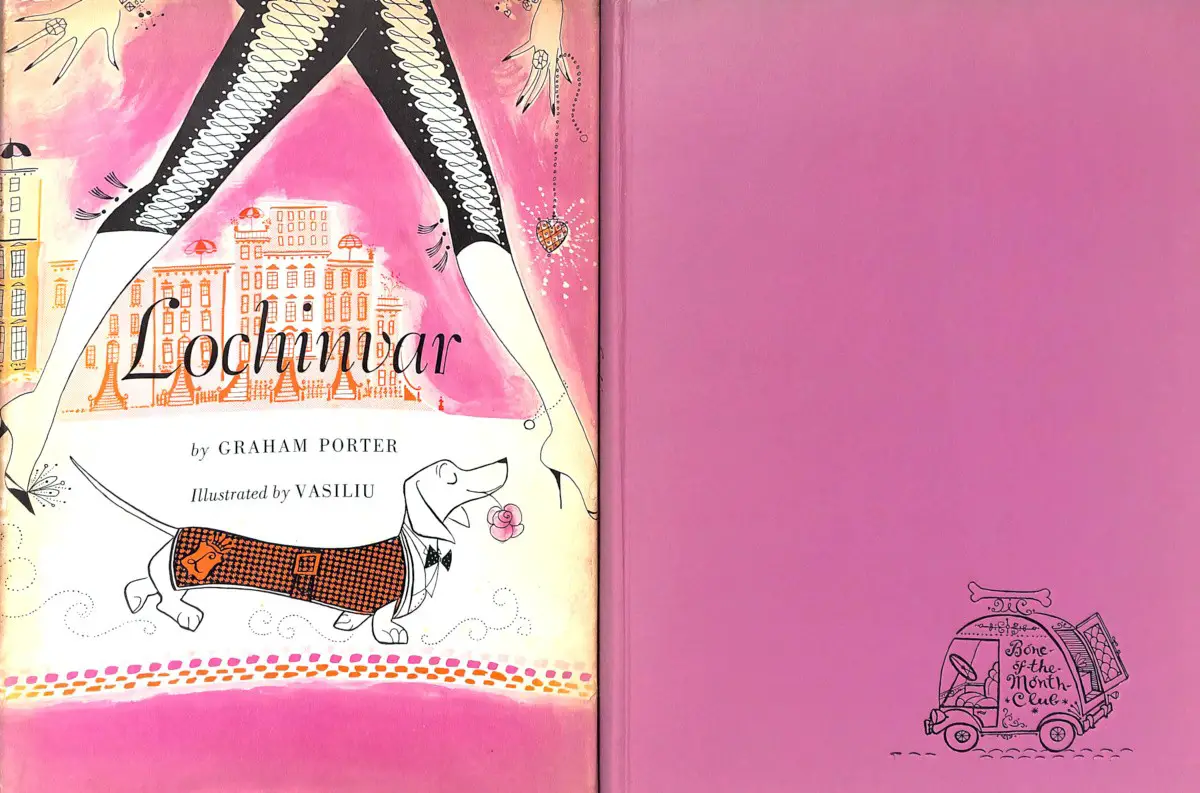

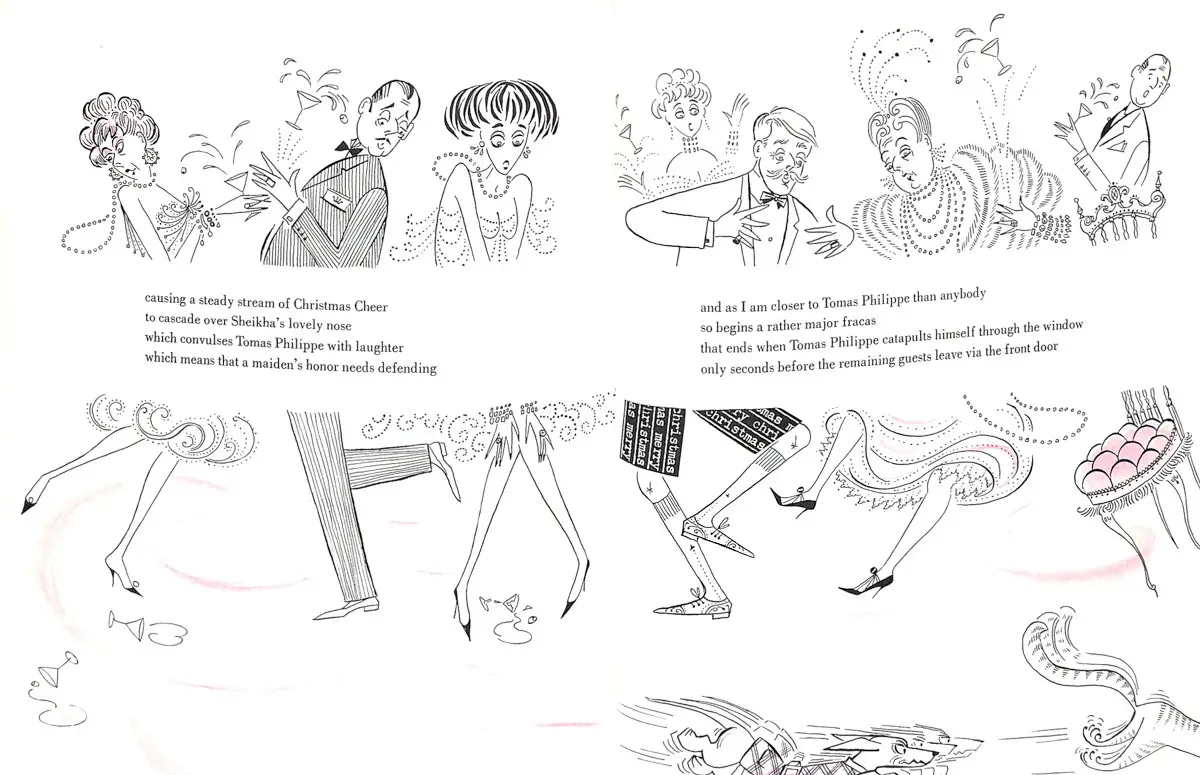

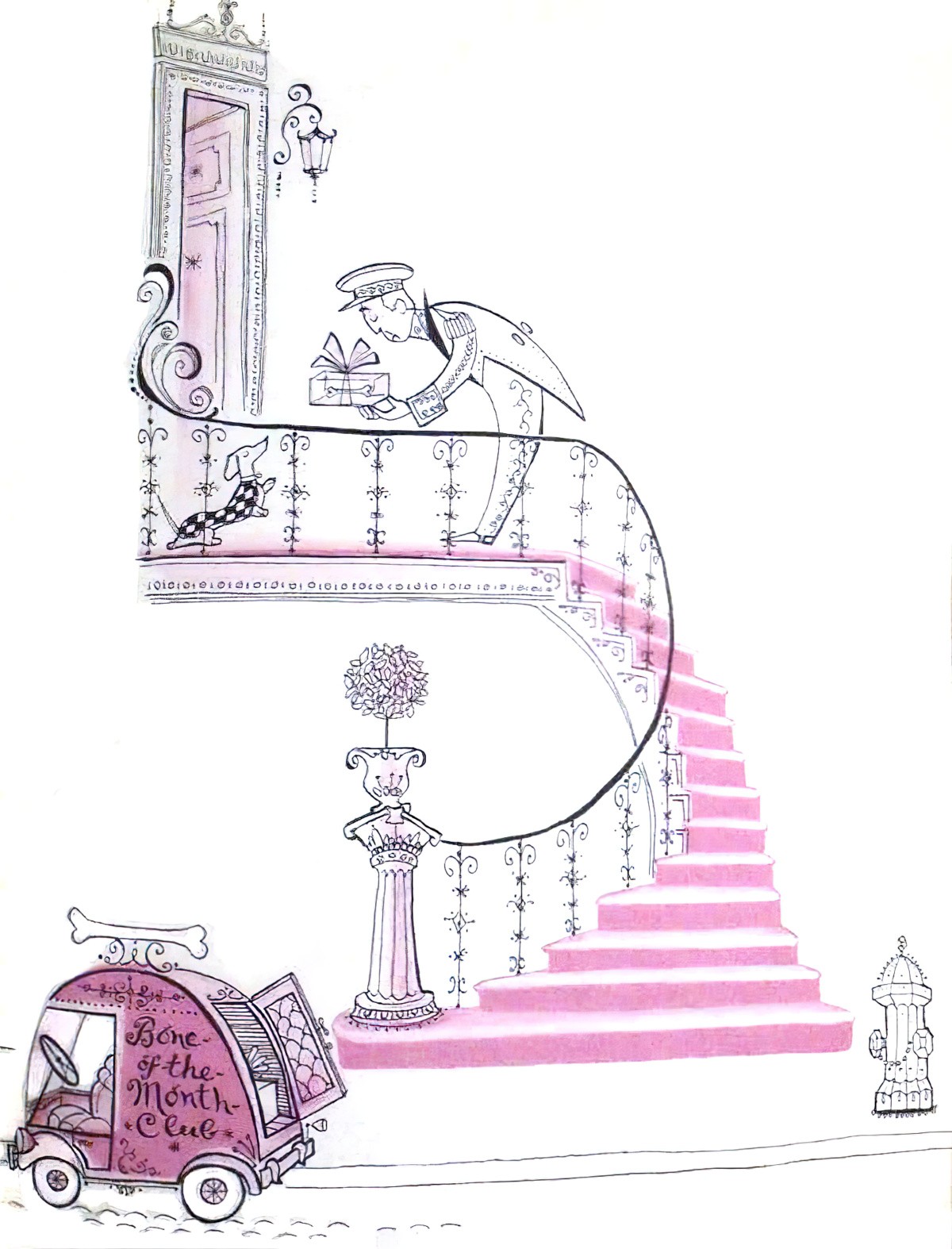

LOCHINVAR BY GRAHAM PORTER AND VASILIU (1959)

There’s a picture book (unambiguously) for adults about a dashing young social-register dachshund called Lochinvar. He travels in a sophisticated set with ‘Mumsy’, the former Mrs. Rippingham Cavanaugh III, and her equally sophisticated social circle. Note that it was published three years after Eloise. I don’t know this story at all, but looking only at the illustrations, wouldn’t mind betting the raison d’etre of this book is: Eloise but for Actual Adults.

Starring the Plaza: Hollywood, Broadway, and High Society Visit the World’s Favorite Hotel

While many authors write about famous films, actors, or directors, Patty Farmer‘s book–Starring the Plaza: Hollywood, Broadway, and High Society Visit the World’s Favorite Hotel (Beaufort Books, 2017)–is about a famous hotel. Built in the early twentieth century, Manhattan’s Plaza Hotel has been visited by many celebrities and used as a backdrop in books, movies, and television. Patty illustrates the hotel with great stories and photographs.

New Books Network