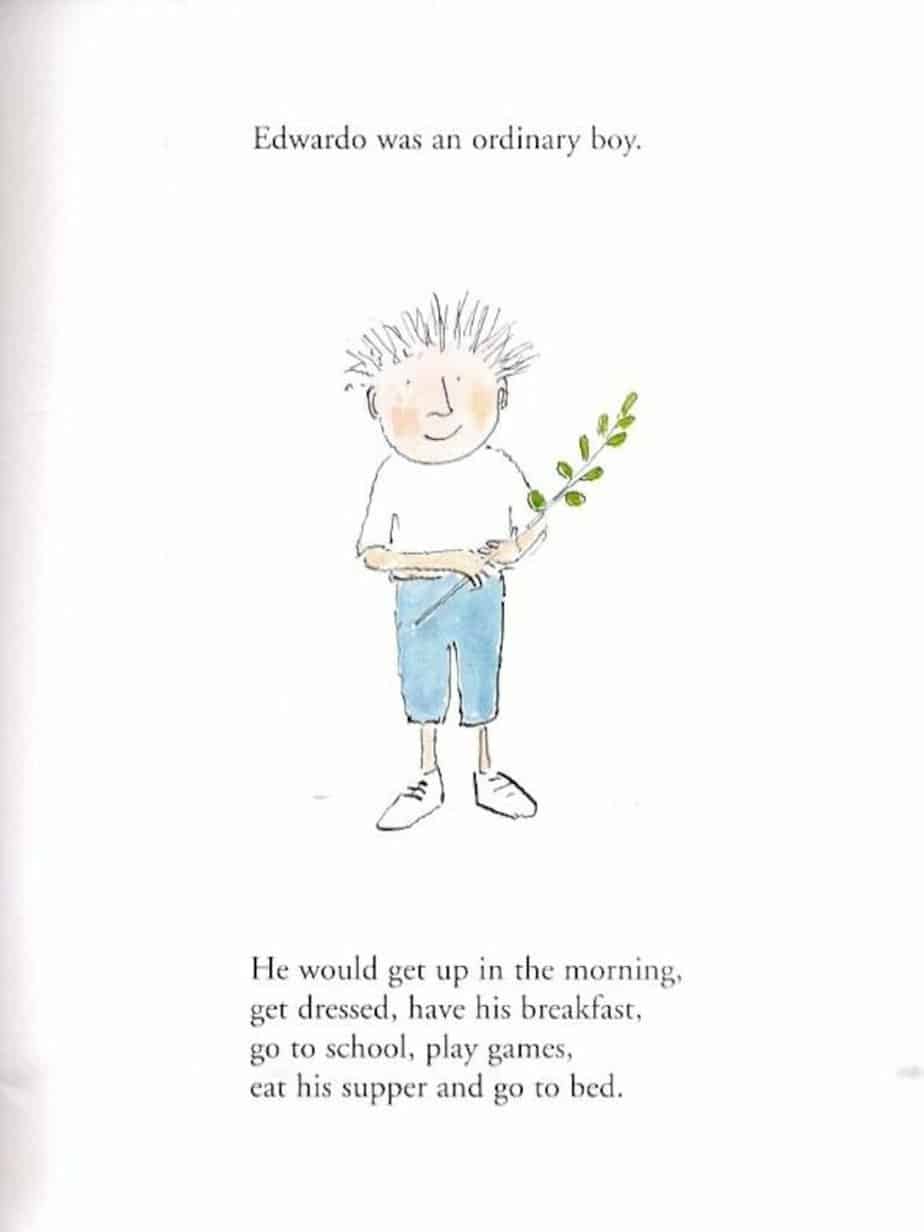

Edwardo, The Horriblest Boy In The Whole Wide World, written and illustrated by John Burningham (2006), is an excellent example of this modern ideology of ‘good’ vs ‘bad’ children, specifically how there is no such thing as good vs bad, but we’re all a little yin yang and can go either way depending on how we are treated.

By the way, how modern is this ‘modern ideology’, really? Despite being reflected in picture books, it is not reflected in the policies of the Australian government. If it were, we wouldn’t be locking up 10-year-olds for crimes, and until last year, that place was in prison.) Australia would not be deporting ‘New Zealand’ criminals who were brought to Australia as toddlers by parents who never got their citizenship paperwork sorted, if we really did believe that environment shapes the child. We would consider those people, for all intents and purposes, Australian. We would let them stay.

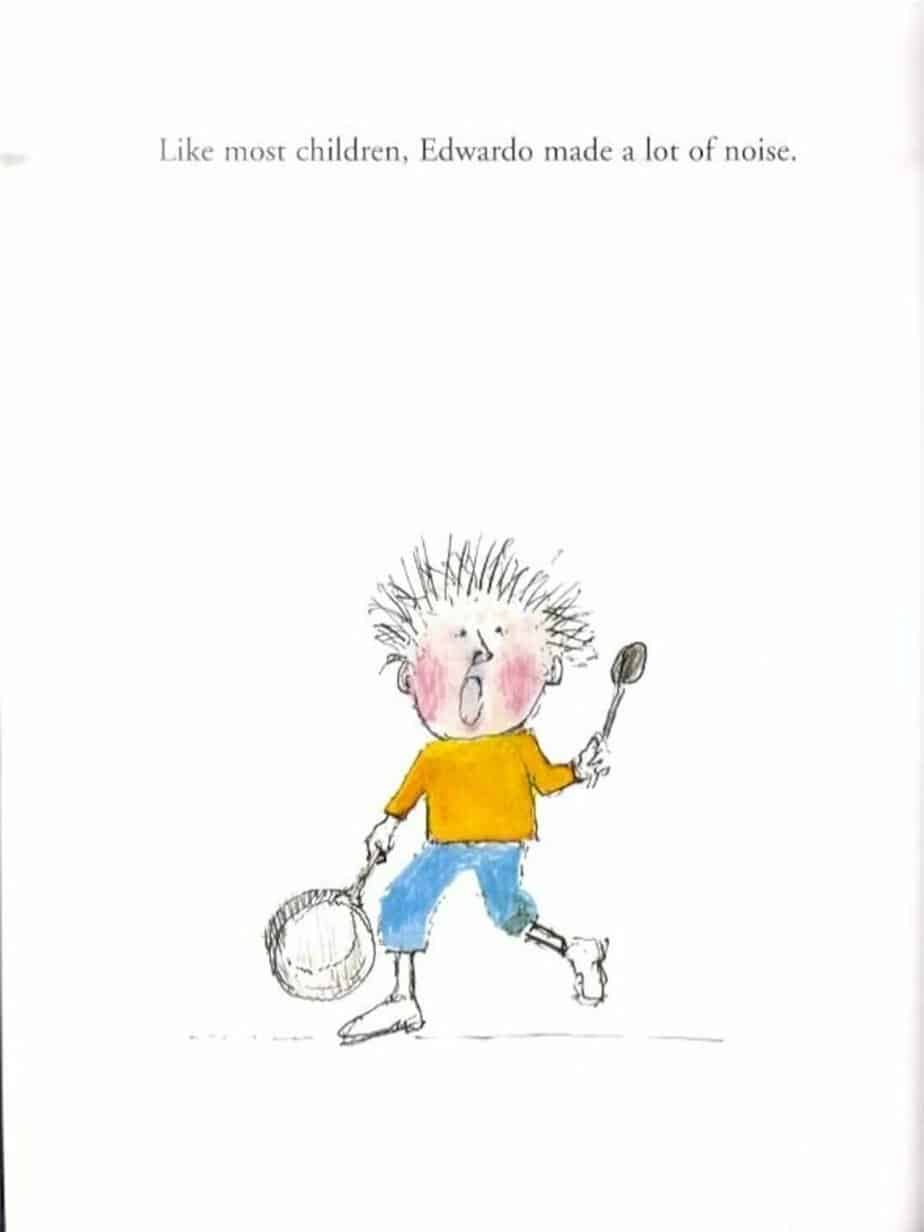

In any case, child audiences love to see child characters behaving badly. Watching children get into mischief is a bit like watching robbers carry out a heist: as audience we never know what they’re going to do until they’ve done it. These characters are intrinsically motivated. They’re the opposite of passive. Interest derives from seeing them get out of their predicaments, or suffering in comedic fashion from their own stupid decisions. (Stupid characters who never learn a thing make great comedic stock.)

Adults love bad guys, too, especially if characters behaving badly are trickster archetypes. Our love for bad guys explains the rise of the antihero in prestige TV — the Tony Sopranos, the Walter Whites, the Ray Donovans.

But the bad guys of children’s literature are not like Tony Soprano, exactly. Contemporary storytellers for children start with the premise that children are partially formed human beings, at the complete mercy of the adults around them, of circumstance. (Even Tony, Walter and Ray get their backstories explaining how they came to be the bad guys. They’re Machiavellian, sure, but not necessarily psychopathic.)

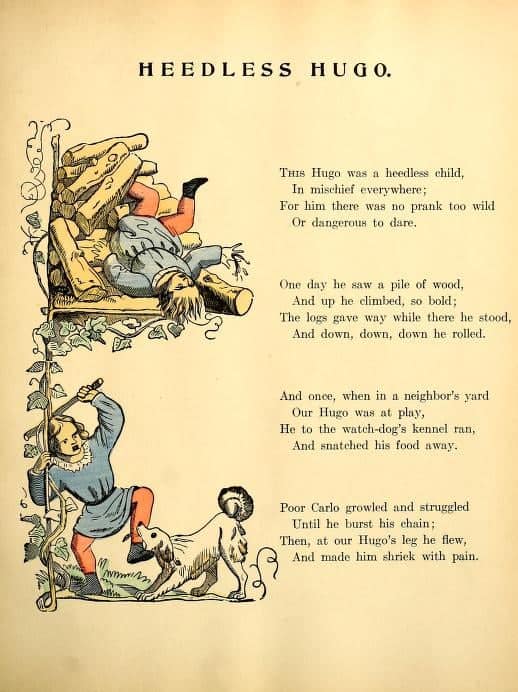

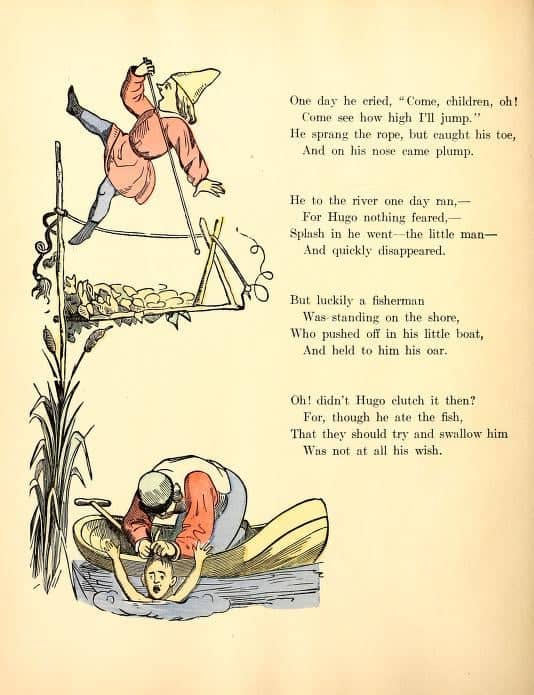

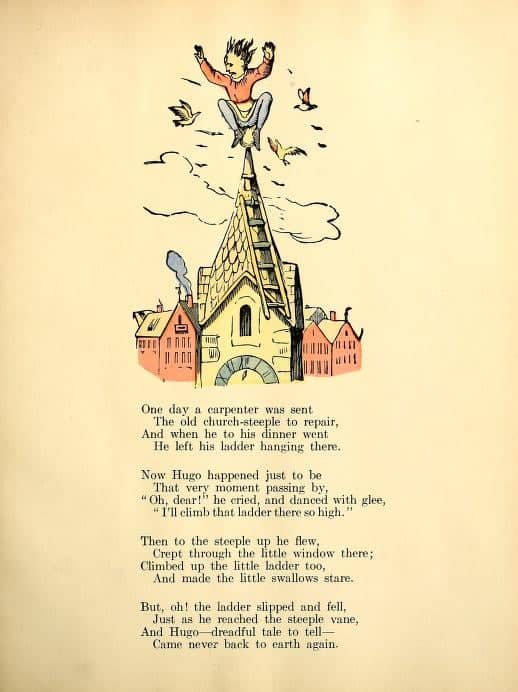

“Heedless Hugo” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich

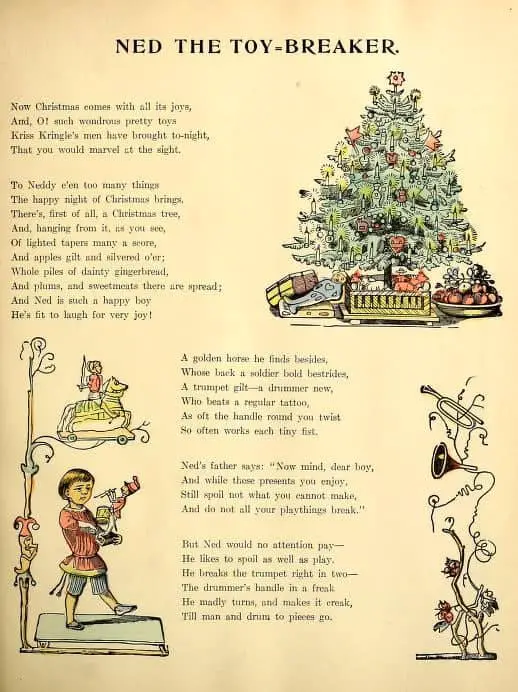

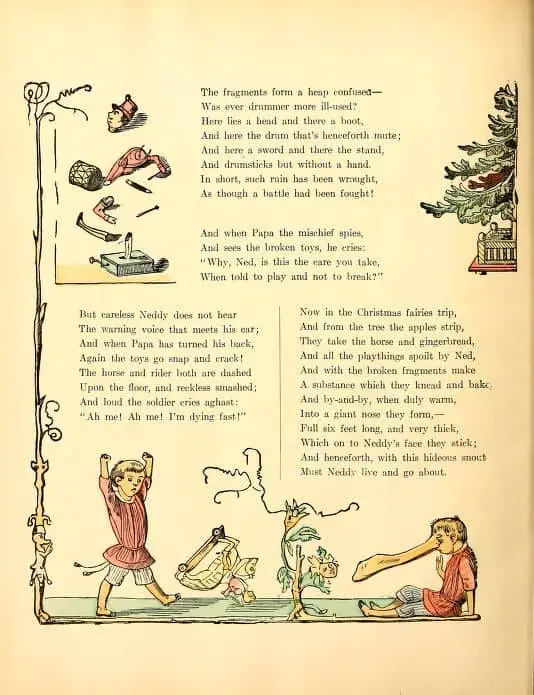

“Ned The Toy-Breaker” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich

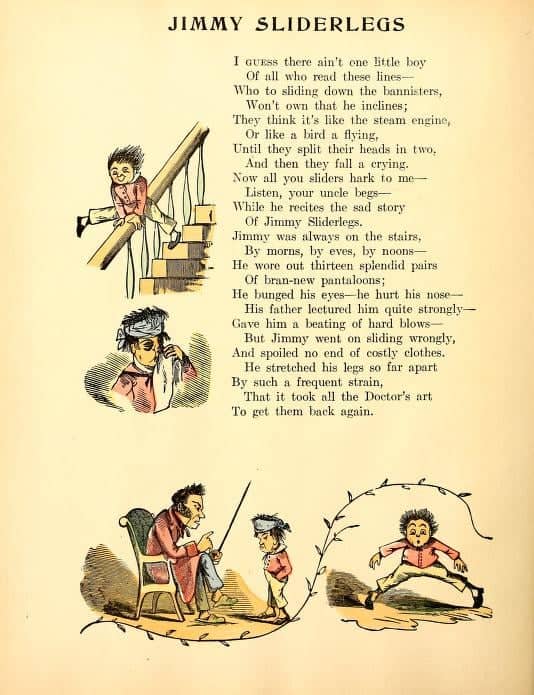

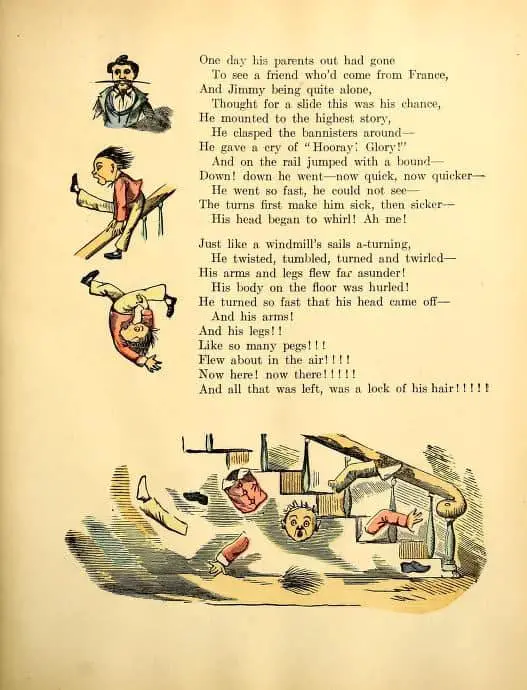

“Jimmy Sliderlegs” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich

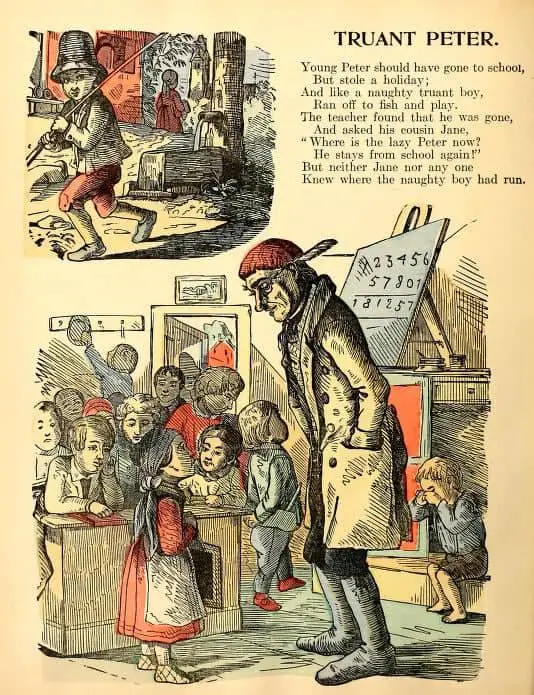

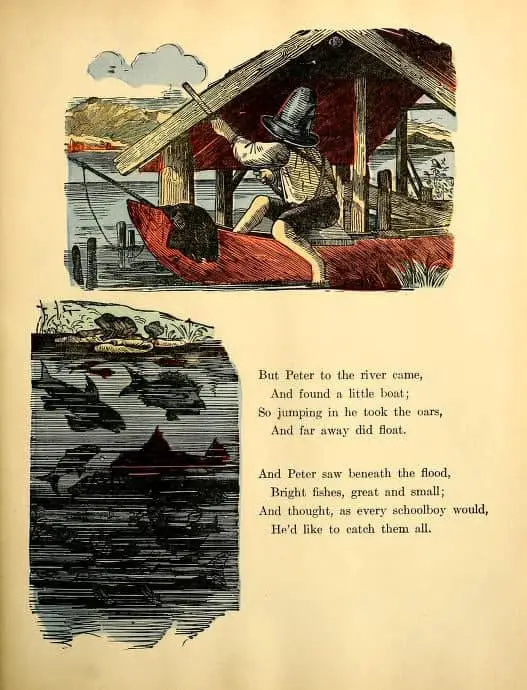

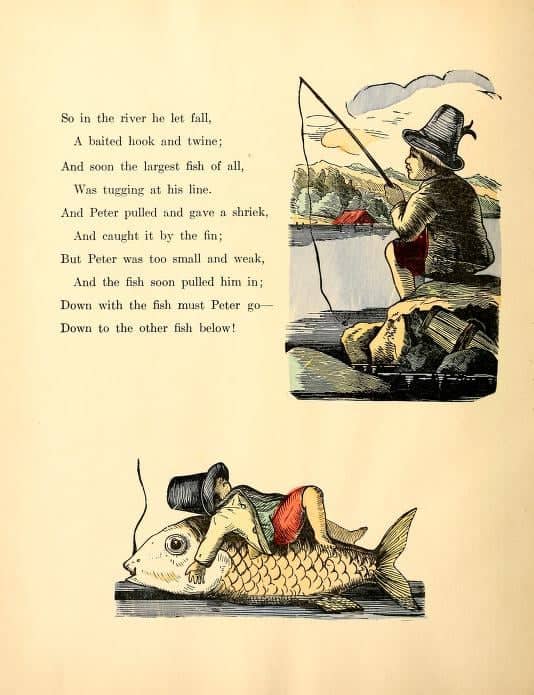

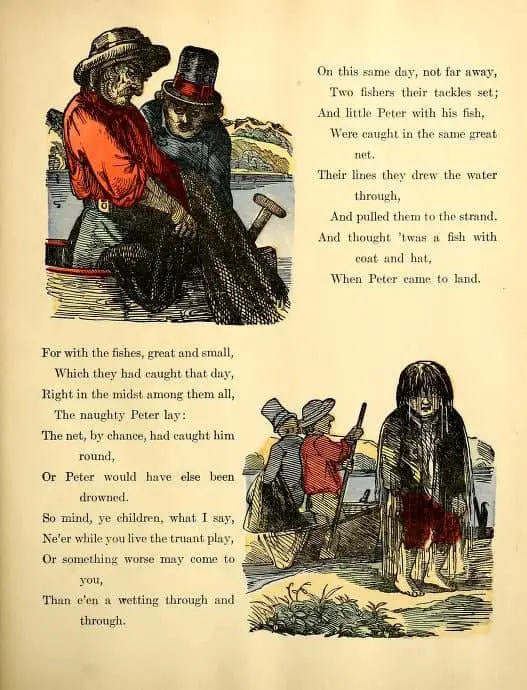

“Truant Peter” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich

MOTIVATIONS OF FABULOUSLY NAUGHTY CHILDREN

These [beastly child] characters are driven by a fierce internal logic that cuts across social convention and the needs or desires of other characters: particularly when they write about children, Potter, Grahame, and Saki characterize bad behaviour as wild, natural, even honest. They do this by associating wildness with animal behaviour; in doing so, they draw on Romantic ideals of the child’s purity and honesty (in the face of corrupt adult society), as well as on ideals of animality. […] However troublesome to adults this behaviour might be, it underscores the natural and original qualities of idealized childhood, in stark opposition to the corruption and mixed motives of the adult world.

Elizabeth Hale, Tooth and Claw

MORAL SHORTCOMINGS IN CHILDREN’S BOOK CHARACTERS

Storytellers are often advised to give main characters a moral shortcoming. This rule of good narrative does seem to apply to stories aimed at an adult audience, but in this one respect, the rules of writing for children work a bit differently. There’s a good reason for that: Children are thought by many to be tabula rasa (clean slate), requiring fictional characters who behave well, or at least learn from their wicked ways. There’s also the carnivalesque children’s story, in which the main child character is flat rather than rounded, standing in for the Every Child. These characters don’t require moral shortcomings or even psychological weaknesses (though they often have these, e.g. being scared of the dark).

There is clearly a place for the ‘nothing’ character of children’s books, especially in carnivalesque stories where the kid could be absolutely any kid. Storytellers don’t want to give them too many defining characterstics because the child reader is meant to jump into their body, so to speak.

But generally speaking, characters with moral shortcomings are the most interesting. This subgenre of children’s book, starring Horrible Children, is therefore a welcome repreive. These kids have bucketloads of shortcomings, moral and otherwise.

THE DUAL AUDIENCE OF EDWARDO, THE HORRIBLEST BOY IN THE WHOLE WIDE WORLD

There are a few ways in which children’s book storytellers can make sure their story will hit the mark for children and adults alike. The big film franchises (especially Pixar) include jokes that appeal to children, but also others that only adults will get.

There’s another way children’s storytellers commonly appeal to an adult audience: Create a lesson for adults as well as for kids. (I reject the commonly cited idea that modern children’s books are not didactic. They absolutely are.) The separate moral lessons in Edwardo are encapsulated by a consumer reviewer below:

It’s a lovely book to read a child. All kiddies like to hear of children even naughtier than they are! But adults would do well to heed the lesson, children believe you when you say what you think they are and will live up to that – or down.

Consumer review

STORY STRUCTURE OF EDWARDO, THE HORRIBLEST BOY IN THE WHOLE WIDE WORLD

Some of Burningham’s stories explore and try to understand the so-called ‘bad’ behaviour of children. Where’s Julius? (1986), John Patrick Norman McHennessy: The Boy Who Was Always Late (1987) and Edwardo: the Horriblest Boy in the Whole Wide World (2006) empathise with the child’s-eye-view, depicting the child’s behaviour with sensitivity, understanding and wry humour. Edwardo’s behaviour is clearly linked to the projections of the adults around him: criticism and derision lead to negative behaviour, while positive expectations and opportunities to learn and grow gradually transform him. Burningham’s skill is his ability to present this as a delightful and funny story, without any overt preaching. As with most of his books, the text is minimal and the illustrations are an integral part of the story.

British Council

PARATEXT

Edwardo is an ordinary boy, so sometimes he can be a bit grubby or clumsy, a bit cruel or noisy or rude. The more that he is criticised, the worse he becomes, until one day they call him ‘The Horriblest Boy in the Whole Wide World’. Just then, Edwardo’s luck begins to change, and a series of chance events reveal that really he is a lovely boy, and has been all along.

marketing copy

SHORTCOMING

Burningham introduces Edwardo by emphasising his ordinariness. (Burningham preferred less usual names, hence Edwardo. But the character of Edwardo is pretty much the Every Boy archetype.) All that distinguishes him from other boys is the bit of branch.

Edwardo’s shortcoming is that, in this particular story, his uber childishness gets him into trouble.

The story does not sit well with some people, who don’t accept the child as tabula rasa, or who, rather, reject Burningham’s hyperbolic depiction of it:

Kind of a cute idea, although I’m not sure about the message. Basically when he was doing things that he thought were being mean, like pouring a bucket of water on a dog, he was thanked for it because the owner said the dog was dirty and needed a bath. No real explanation for how doing something mean goes to being thanked for it and then… being asked to have more responsibility, ie watching kids, taking care of dogs in the neighborhood, etc. OK, but shaky in terms of it’s teaching…

consumer review

The more geneticists learn, the more it is widely understood that people are a complicated, cyclical product of ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ (often posed as a false dichotomy). If you’ve ever delved into the literature on criminal psychopaths, or watched too many true crime shows, you’ll understand that harming animals is a common (though not universal) feature of childhood behaviours of adult killers.

Burningham does not intende for us to code Edwardo as a proto-psychopath here. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that Burningham is ratcheting everything up to hyperbolic levels — a common trick utilised by children’s storytellers, who often play around with scale and magnitude, but with anything at all, really.

Perhaps it is this animal-cruelty detail that makes me wince a little when Edwardo is subsequently entrusted with people’s animals, then with their children. Everything in this book is hyperbolic, including his rapid turnaround. This story won’t work unless we’re able to run with the fun of exaggeration and suspend disbelief. I’m guessing children are better able to do this, which makes this book mainly a book for children, despite the clear lesson for adult co-readers.

Bad Guys don’t work unless they’re a little bit loveable. Edwardo is holding a bit of branch when we first meet him. This is the only thing that distinguishes from every other Every Boy. We will eventually learn that he likes to garden, a trait associated with the best of people.

DESIRE

Edwardo is a melodramatic hero in that he is going about his life and all around him things are happening which will dramatically change his equilibrium.

His deeper desire is that he needs attention. Like everyone, he wants to be seen and if he doesn’t get attention for the right reasons, he doesn’t have the tools to get on with his life anyway, so he’ll do anything possible. He subconsciously learns that behaving badly is a surefire way to get the attention he needs. Even for those parents who haven’t had to sit through lectures on B.F. Skinner, this is hardly a revolutionary parenting idea. However, the idea that we all live up or down to expectations will be novel for children.

OPPONENT

Edwardo’s opponents are every single adult he comes into contact with. They want him to be quiet and well-behaved, but by doing this, he wasn’t getting any psychological reward. He was previously ignored, we deduce.

PLAN

Edwardo will live up to his bad reputation by doing worse and worse things…

THE BIG STRUGGLE

… culminating in animal abuse.

ANAGNORISIS

How does Burningham turn this pattern of behaviour around? A different storyteller might bring in a sympathetic adult who understands him, perhaps a Miss Honey archetype a la Matilda. But this story wouldn’t be ‘enough’ if that happened. Plus, storytellers for kids want to avoid bringing in adults to fix things (or kids themselves). It feels like deus ex machina, and also takes autonomy out of the child’s hands. That’s exactly what kids like about bad kids in the first place! So we want to avoid that.

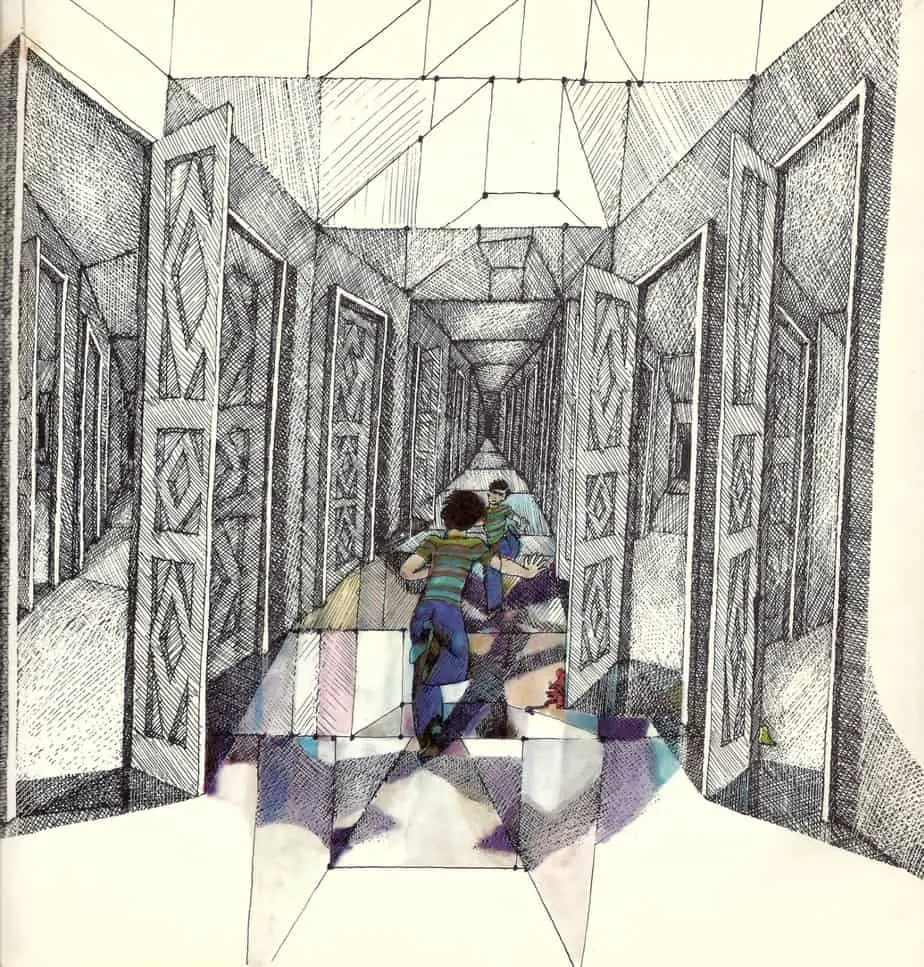

Instead, at about the halfway mark, Burningham makes the universe come to Edwardo’s rescue. If readers find this story funny, the humour is of the Mr Magoo variety, where a character ‘blind’ (literally or metaphorically) to the workings of the world and their own autonomy within it is saved by the very same world, which conspires to take them on a madcap adventure, but always safely.

These comedic adventures are full of coincidences, and in fact requires them. So when Edwardo throws everything in his bedroom out of his window, there is coincidentally a charity wagon waiting to collect everything down on the street below.

This story is clearly part of the comedy genre, because comedic characters don’t have self-revelations like the heroes of more serious works. Edwardo doesn’t suddenly become a good kid, but then, he was never a bad kid in the first place. It may take a reread to remind ourselves of that, because the opening image of Edwardo is soon forgotten, replaced by more resonant imagery of mischief.

NEW SITUATION

Edwardo’s family now think he is the best boy in the whole wide world. The reader is assured that Edwardo has not morphed magically into a Mary Sue archetype, from evil to perfect, but is instead a mixture of faults typical of all of us. Burningham wants us to find Edwardo relatable. The ending ensures it.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Edwardo may be relatable, but he’s not the slightest bit realistic, and nor was he meant to be. I’d be worried about any kid torturing animals. I’d take them for a psychological assessment.

RESONANCE

Stories about fictional naughty kids have been around for as long as children’s books have been around, and continue to resonate with audiences, even though the plots themselves are less about revenge and punishment, more about humour, and in this case, the ‘universe’ steps in to change things around. There are still complexities to work through on this point, though.

Take John Marsden’s picture book Millie, about a naughty girl. In the story she goes unpunished, which irritates some modern adult gatekeepers of children’s literature. Compared to Marsden’s other works, Millie hasn’t found longevity even here in Australia, despite the best-selling author platform. There are probably some gendered issues at play, which would account for the prolifertion and popularity of loveable naughty boys and adult male antiheroes, versus the dearth of female analogues. Even the cutesey Junie B. Jones is considered too much trouble for some adult gatekeepers.

Although boys display more aggression in schools and are excluded at higher rates accordingly, a problem in its own right, I suspect that in picture books, as in real life, girls are judged more harshly (or at least differently) when displaying the exact same levels of aggression. When girls act out they are defying gender expectations on top of the general expectations for everyone. (And it’s worse again for Black girls.) As starting evidence, we have consumer reactions to the naughty boys of children’s literature versus reactions to the naughty girls. We end up with far more naughty fictional boys, and the ‘naughtiness’ of the girls (Anne Shirley, Eloise, Ramona Quimby, Junie B. Jones, Judy Moody, Clementine) is qualitatively different. Compare Otis Spofford (male) to Ramona Quimby, both by the same author. The naughty girls of children’s literature are often coded as ‘moody’ (lacking in emotional regulation) whereas the boys are simply being natural boys, in a world which fails to afford them sufficient freedom to stretch their boyish wings.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF STORIES ABOUT NAUGHTY KIDS

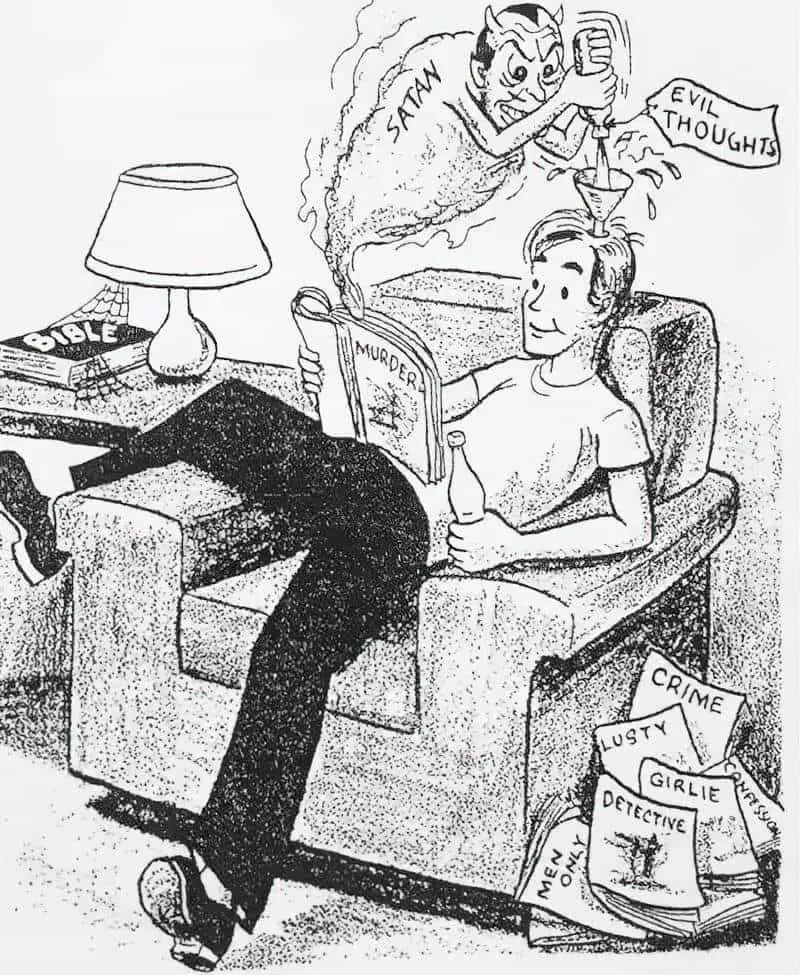

In the early days of children’s books, adult gatekeepers seemed to see the good in stories about retributive justice dished out to naughty children. This was an earlier form of didacticism. Don’t be naughty like this child, or this punishment will happen to you!

Frank Henry Bellew’s A Bad Boy’s First Reader (1881) is one early example.

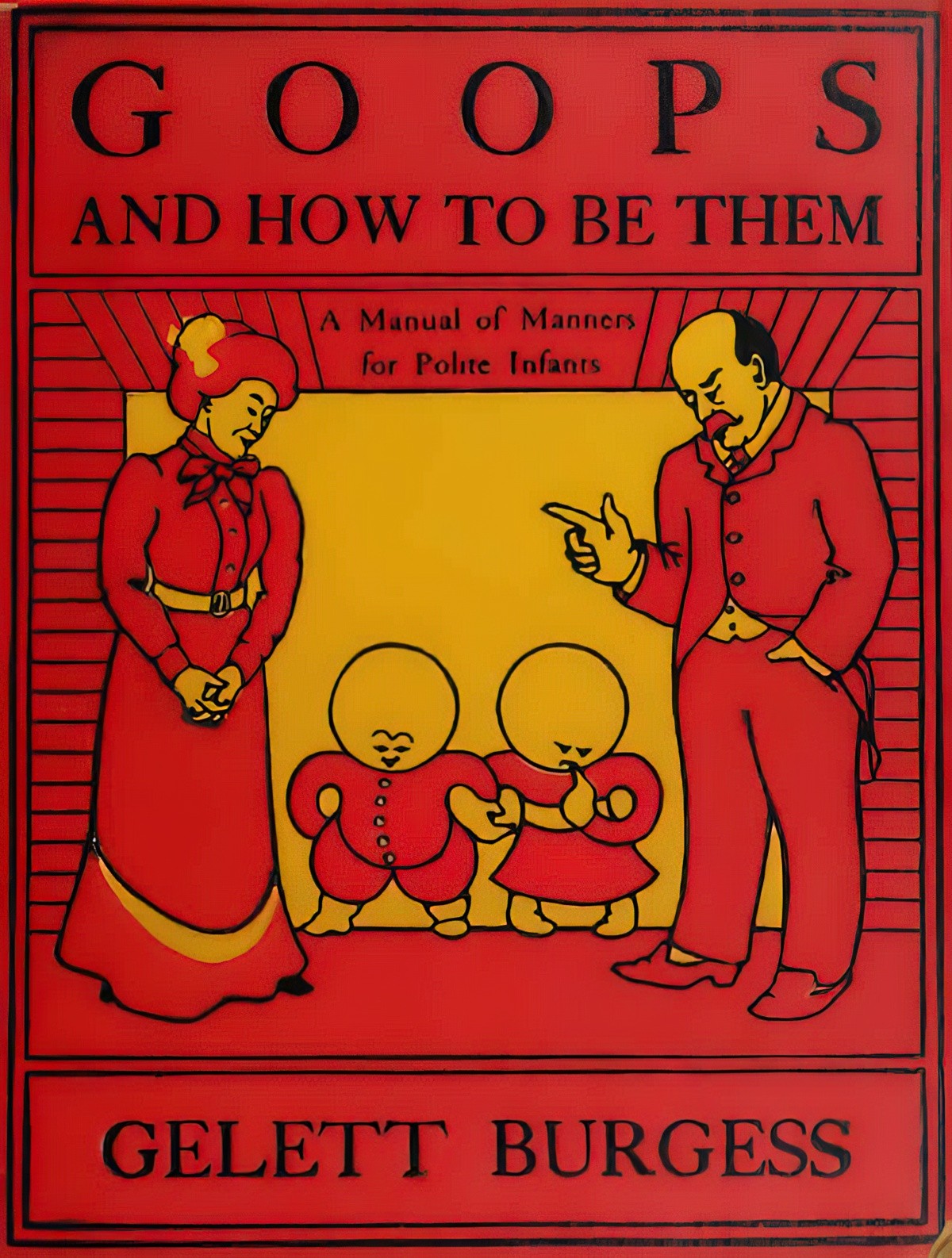

The most resonant of these older Naughty Children books are poking fun at the more serious books of their very own era. I offer for your reading pleasure Goops And How To Be Like Them: A manual of manners for polite infants by Gelett Burgess, published in 1900.

Hilaire Beloc followed in Goop tradition and famously parodied the didactic manners genre in CautionaryTales For Children (1907) by creating totally over-the-top sadistic punishments for his child characters. (This book was illustrated by Edward Gorey. Remove the ‘e’ and Gorey has a wonderfully aptronymic name.) These tales are meant for adult readers who’ve grown up (and grown weary of) the heavy didacticism from their own childhood.

Naughty kids in literature never ceased over the course of the 20th century. Beastly Boys and Ghastly Girls by William E. Cole, illus. by Tomi Ungerer is a 1964 example.

The tradition continues in modified form. Horrid Henry is a best-selling English series of early readers and chapter books by Francesca Simon, illustrated by Tony Ross.

America already had Horrible Harry and Rotten Ralph. Note that Harry and Henry are archetypal Every Boy (white boy) names, with only the class difference to distinguish them. These fictional boys get up to all sorts of mischief, and although they’d be unpleasant to hang out with in real life, no doubt rejected by the same children who enjoy reading about them, these boys indulge in carnivalesque mayhem. Wouldn’t we all like to indulge in the sensory pleasures of tipping paint out of its can, unravelling the toilet roll? On top of that, I’m sure the misadventures sometimes appeals to the child reader’s fantasy of revenge. (It often involves a pretty girl being soaked or made dirty. Ellen Tebbits does enjoy her own revenge, for which I’m grateful.)

FURTHER READING

“The Boy Who Became a Goblin” is a Swedish fairy tale about a young troublemaker who doesn’t believe goblins are real until he’s kidnapped by them. The goblins have a very sinister plan in mind for him.

If you’d like to hear “The Boy Who Became A Goblin” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and Foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Boy Who Became a Goblin” was published July 2021.

Changing ideas about the effectiveness of retributive justice and punishment are reflected in children’s stories. In earlier times, fictional children were commonly beaten or denied food.