“A Case of Eavesdropping” is a ghost story by Algernon Blackwood first published in December 1900 in Pall Mall Magazine.

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE STORY

A common eavesdropping storyline from folk tale:

An eavesdropping sexton is duped into giving a suppliant money. The trickster prays to the Virgin for a certain sum of money and promises repayment of double at the end of the month. The sexton throws the money to him, but never receives it back. (See the OTHER CHEATS entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.)

Other eavesdropping entries from Baughman’s book:

- Eavesdropping person unwittingly killed

- Eavesdropping man in disguise as devil killed unwittingly by daughter‘s lover.

- Eavesdropping wife hidden in bushes killed unwittingly by husband

- Secret about prince’s father learned by eavesdropper from his mother‘s talking to him.

- Secret name overheard by eavesdropper.

- Secret age overheard by eavesdropper.

- Secret reason why hero does not want to eat the food of the foreign king overheard by eavesdropper.

AND in this PARTICULAR eavesdropping story

American man Jim Shorthouse has led a chaotic life. It reads to me like a case of undiagnosed, unaccommodated AD/HD and possibly autism. Note that we’re not supposed to feel sorry for him (yet). What happens to him is ‘karma’.

Jim Shorthouse was the sort of fellow who always made a mess of things. Everything with which his hands or mind came into contact issued from such contact in an unqualified and irremediable state of mess. His college days were a mess: he was twice rusticated*. His schooldays were a mess: he went to half a dozen, each passing him on to the next with a worse character and in a more developed state of mess. His early boyhood was the sort of mess that copy-books and dictionaries spell with a big “M,” and his babyhood–ugh! was the embodiment of howling, yowling, screaming mess.

*a simple or old-fashioned style of living or decoration that is typical of the countryside OR the act of making someone leave a place, especially a private school or Oxford or Cambridge University, as a punishment.

The guy comes from a wealthy background and great things were expected, but he was twice ‘rusticated’ (suspended) from his private college. Things didn’t improve after that. His father stopped supporting him financially at the age of 22.

Algernon Blackwood fast-forwards the story to tell us that, at the age of 40, Jim meets ‘a girl’ who straightens out his messes. This girl is wealthy, which we deduce will help him out with his debts, at least.

Rewind. What happened to Jim right after his father refused to support him? He moved to the city and talked his way into a job as a reporter at one of the daily journals. After all, he is the observant type, and he is expensively educated. During the interview he wore a shabby old suit that belonged to an uncle. He had to stand weirdly so the newspaper guy wouldn’t notice the holes. The newspaper was in the habit of hiring a whole lot of young men at once, giving them all a week’s trial then retaining only the top few, so Jim gets his chance.

He sews up the holes in the suit then sets about finding accommodation, or “diggings”. Without much money to live on, he could either live in a boarding-house or in a room-house. Boarding houses have all these rules about how you must live your life and what time you must eat, so he decided to find a room-house.

A ‘room-house’, or rooming house, was a low-rent dwelling with small private bedrooms and shared bathrooms down the hall.

This room-house In the 1800s, boarding with families was commonplace for people of all ages. As many as half of urban Americans spent part of their lives either as boarders in others’ homes or as hosts of boarders in their own … As the 1800s turned to the 1900s and North America urbanized, other options proliferated. For the working class, an abundance of rooming houses opened. Some offered boarding as well, with a kitchen and dining hall in the basement or on the ground floor. For the poor, cheap lodging houses provided basic accommodations for low prices. Some had small private rooms. Others had grids of open-top cubicles. Still others offered bunk rooms or rows of hard-slab “flops.” In San Francisco a century ago, five-sixths of hotel dwellers were either working class or poor, and a passable room might cost 35 cents a night ($8 in today’s currency).

Alan Durning

So Jim rocks up to his room-house, which looks on paper like something straight out of a Gothic horror. It’s got the dirty windows, the creaking iron gate, you name it. In its favour: large rooms. He can’t back slowly away because he’s already paid in advance for a room on the top floor.

What a landlady. ‘Gaunt and dusty’. Green eyes. So is she a ghost or a witch? OR BOTH?

The landlady speaks with a Western drawl. She reassures Jim, who is hesitant, that if he doesn’t want the room it doesn’t hurt her any. Take it or leave it.

Jim takes it. Any other guests? he asks.

We do not ask questions like that.

But yes, since you asked, there is DEFINITELY one old guy who’s been staying here at this very room-house for the past five years.

I’ll take it, says Jim, short on funds and other ideas.

Jim is kept busy by his reporting work. He stumbles back to the room-house in the small hours. The house is very quiet. He sees no one.

One night, in his second week, he returns ‘home’ after 2 a.m. to find there’s no lamp in the hall. He can’t see a thing in the darkness, and bangs and crashes his way up to his own room.

He’s getting ready for bed, faffing around with a bit of light reading, when he hears footsteps from the floor below. THE FOOTSTEPS ARE MAKING THEIR WAY UPSTAIRS.

Heavy footsteps. FAST, HEAVY footsteps.

Must be the old guy. What’s he doing up at this hour? Must be his habit to turn out the gas.

The footsteps stop right outside his own room.

Someone knocks on his door!

Like Llewellyn in No Country For Old Men, Jim Shorthouse turns out his own light. Everything’s dark as pitch now.

Then Jim hears a voice. RIGHT IN HIS EARHOLE. The voice speaks German. Jim speaks German himself and knows what the voice said: “Is that you, father? Come in.”

Okay, so the voice sounded close, but it actually came from the room next door. Jim has heard through the wall. HE THOUGHT THE ADJOINING CHAMBER WAS VACANT. The landlady told him so!

Those walls must be very thin because Jim hears everything happening in the room next door. The inhabitant crosses the floor to unlock the door. The guy in the corridor says, “Let me in!” The door slams shut. Chairs are drawn up to a table. These guys don’t give a crap about anyone else’s sleep. Then again, Jim wasn’t exactly quiet himself, was he.

Jim figures the old lady has let out the room next door very recently.

The guys next door are arguing in German. Jim speaks German, sure, but he learned it in school, probably. He understands the odd word: “Father”, “Otto”. Eventually he gets the gist. This father is trying to persuade his son to take his new wife’s trust money and give it to him to save the family business. He reassures the son it will all be paid back. The son says he can get half but not the entire amount. The father says if he can get half, he can get the lot.

Jim starts to feel bad for eavesdropping, so coughs loudly, announcing his presence. The guys through the thin wall ignore him.

Next, Jim gets annoyed. He needs his sleep, dammit. So he goes out into the corridor and knocks on their door. The voices stop immediately. Utter silence. Not even a light under the door.

Jim asks in German through the keyhole if they wouldn’t mind keeping it down. No one answers. Jim tries the door handle. The door is locked. It’s cold. He shivers.

Shadows in the corridor give him the creeps. Now the house is too silent. He gets into his own bed and falls asleep.

Next morning. Jim decides to complain to the landlady about his noisy neighbours who ignored him when he asked them VERY NICELY to please be quiet.

It ‘just so happens’ the landlady is nowhere to be seen!

That night, Jim peers under the door to check those Germans aren’t in. They’re not. Good. He falls asleep around one. If they start up again, he will INSIST the landlady reprimand him. The landlady is scary, and very good at reprimanding.

However, he sleeps well, and dreams of pastoral scenes. Sheep and cornfields.

TWO NIGHTS LATER.

There’s been a wicked storm. He’s also tired from work. He takes off his wet clothes and gets into bed under cosy warm blankets. He’s in that liminal space between awake and asleep when he hears sounds that are neither wind nor rain. He also feels… uncomfortable.

He’d been dreaming about sheep. NOT ANYMORE. The sheep of Jim’s dreams are running away, frightened. The sky grows dark. The sheep run into the corn.

Jim wakes from his nightmare. The sound in his dream was coming from inside the house!

In the distance, a church clock strikes two. (Two must be witching hour.) Although he’s safe and warm in bed, he starts shivering uncontrollable, like a young man come down with some horrible disease. If those Germans start up again next door, I don’t even… I don’t know what I’ll do!

Yes, great. Footsteps in the corridor.

Energy leaves Jim’s body. But his senses are on high alert.

A heavy body brushes his own door. Then he hears the knock on the door next to his.

The father has come once again to visit the son, who still refuses to hand over his new wife’s trust money. But the father has stolen her jewels. The son tells the father he will never have them. Next, the father murders the son. Jim hears every bang and crash. Not only that, the wall and floor moves. Something heavy is going down next door.

Jim has his hand on his doorknob, about to run to fetch the police, when he notices out the corner of his eye something move in his own room. It is dark and snake-like. He touches it. It’s warm! And covered in blood. Now his own fingers are stained crimson.

He looks out the window through the rain to the city beyond. He feels as if someone is about to hit him. He raises his arm. Suddenly the landlady is there with him, holding a sputtering candle.

He’s in his striped PJs and bare feet. The room is completely empty, except for himself and this landlady.

The landlady, comically, supposes he can’t sleep and that’s why he yelled. Or maybe he’s just been prowling round a bit? (That’s what young men are wont to do, right?)

Landlady: You ain’t seen sh!t.

Also the landlady: Well, I guess you saw whatever scared the others off. Also, ain’t you an English gentlemen, not flighty and from a background of folklore like those other chaps?

Shorthouse considers throwing the dusty old woman over the bannisters.

Instead, he shows her the blood on his finger.

Jim: Check out my finger. Am I imagining THAT, you old bag?

Landlady: [LONG SILENCE] Yep.

Jim looks down at his finger. THE BLOOD IS GONE. So is the pool of blood on the floor. He’s going out of his mind! No creeping, no crawling, no bulged partition wall…

The landlady says she’s going back to bed. Her candle throws a queer shape along the wall and ceiling. Also, she tells Jim “it never comes back after it’s killed”. I like this old bird. “I’m no spirit medium. You take your chances.” Also, there is no older gentleman. The old bird only told Jim that to make him feel less alone.

Oh and also, by the way, how did you feel? Landlady’s only asking because the previous guy, he was found dead in his bed, so you might want to watch out for that. If you get a queer, unhealthy feeling, like.

If I were Jim I’d be cranky with the landlady for playing fast and loose with my life. Instead, Jim listens with reporter’s interest as the old woman fills Jim in on the backstory. This place used to belong to a German family. The father worked on Wall Street. The son died by suicide, so it is thought. The reader deduces at this point that the ghost of the son is trying to persuade subsequent boarders of the truth by re-enacting for them the series of terrible scenes.

The landlady shows Jim an old bloodstain on the floorboards.

Now for the epilogue paragraph:

As for Jim, he slept in a hotel the following night. Then he found himself some new digs. With access to historic newspapers, he uses his position as a reporter to verify the more detailed story of the German guy who killed his own son. This only confirms what the landlady told him. The father absconded and was subsequently arrested, though not for the murder of his own son, so it seems.

DESCRIPTIONS OF EAVESDROPPING AND OVERHEARING IN FICTION

The following excerpt is a very nice description of when you hear something but can’t quite make out the words, but are able to fill in a few details anyway:

A hand on the cool wood of the library door, she listened. She still could not hear what was being said; she could only hear that something was; so it wasn’t really eavesdropping, was it? And still Mrs Hill talked, and talked, and the longer she talked the stranger it became that she was still talking. Mr B. would lend you a book, but he didn’t want to hear what you thought about it. He’d say thank you for any service you performed, but he wouldn’t even catch your eye. How could she have so much to say to him, and why — and this was the truly baffling thing — was he just letting her go on saying it?

Then something changed. Three words from Mr Bennet, like dropped stones. You may go, Sarah guessed. She raced on tiptoe back down the hall, slipping through the open door into the servants’ corridor. Heart pounding, she crouched to lift the chamber pot, then peered back the way she’d come.

Longbourn by Jo Baker, a re-visioning of Pride and Prejudice but from the servants’ point of view.

He looked out the window. The sun was higher, the light beginning to slide down the ladder of the windmill, brightening it, making rungs of rose-gold.

When he turned again to the bed he saw by the change in their faces that they were awake now. He went out into the hall again past the closed door and on into the bathroom and shaved and rinsed his face and went back to the bedroom at the front of the house whose high windows overlooked Railroad Street and brought out shirt and pants from the closet and laid them out on the bed and took off his robe and got dressed. When he returned to the hallway he could hear them talking in their room, their voices thin and clear, already discussing something, first one then the other, intermittent, the early morning matter-of-fact voices of little boys out of the presence of adults. He went downstairs.

[…]

Downstairs, passing through the house, Guthrie could hear the two boys talking in the kitchen, their voices clear, high-pitched, animated again. He stopped for a minute to listen. Something to do with school. Some boy saying this and this too and another one, the other boy, saying it wasn’t any of that either because he knew better, on the gravel playground out back of school. He went outside across the porch and across the drive toward the pickup.

Plainsong by Kent Haruf (1999)

VARIOUS EAVESDROPPERS IN ART AND ILLUSTRATION

Herbert Clark, the psychologist, devoted some of his work to types of roles which we play when communicating. He suggested that there are a number of listener roles. First, there is the addressee…There are also side participants, i.e., those who are not addressed, but are socially/interactionally ratified to listen to what is being said. The speaker is also aware of their presence (there was no such person in our conversation).

Similarly, the speaker is aware of the presence of a bystander. They are openly present, within the earshot, so they can overhear what the participants say, but they are not part of the conversation. … This is when you are listened to by someone you are not aware of.

Eavesdroppers, linguist Dariusz Galasiński

When there’s a mystery to be solved in a story, especially in a children’s story, the character very often begins their journey after hearing a conversation they weren’t supposed to hear. The Golden Compass begins like this. Another example is The Halfmen of O by Maurice Gee. For a picture book example see The Stranger by Chris Van Allsburg.

There are many other eavesdropping scenes which open stories for children.

Why? Because children don’t start with the same information that adults have, and are protected from evil by those who love them. Also, don’t we all learn most of the things from overhearing and observation during childhood?

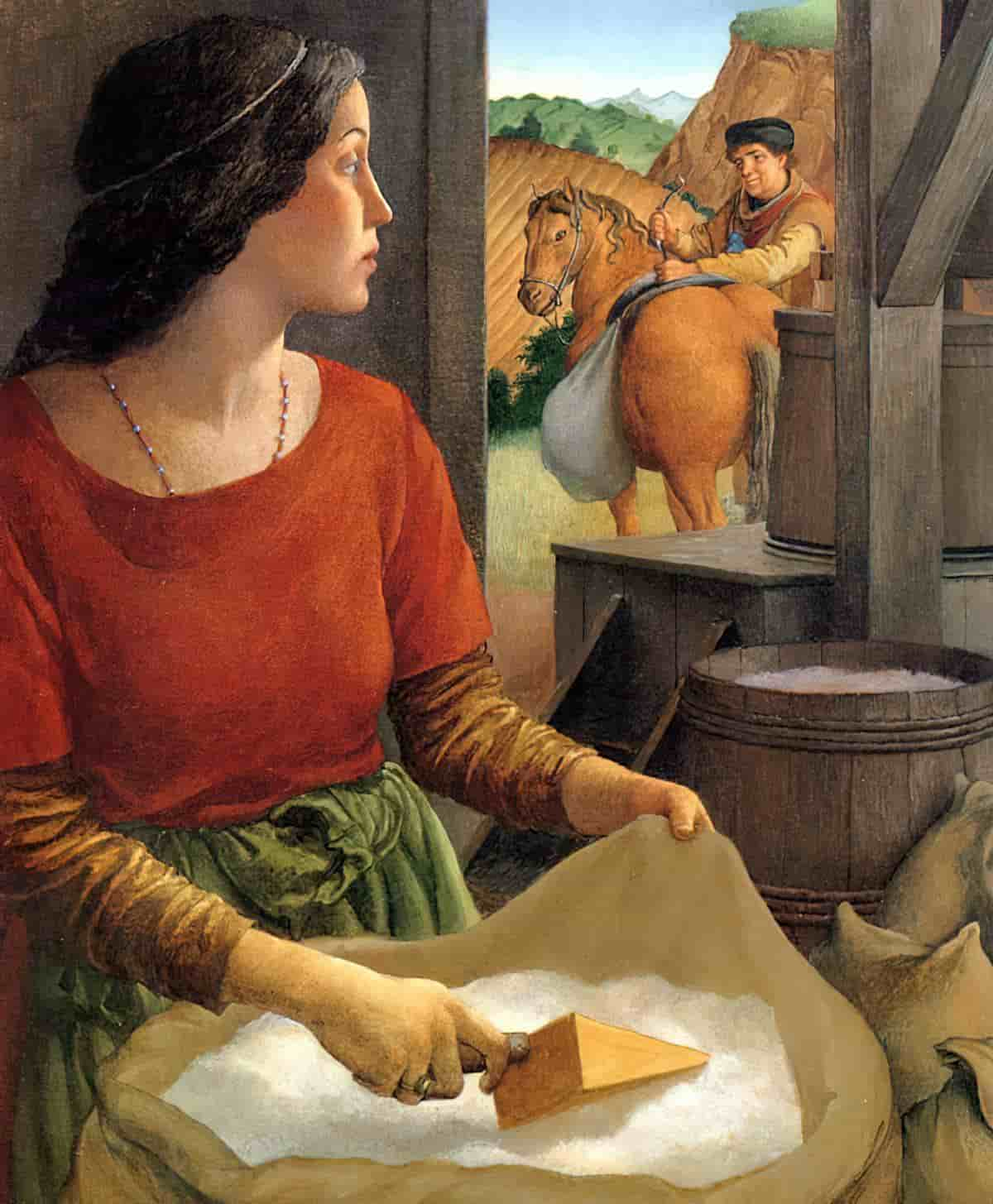

Since women are historically infantalised, there are many artworks which show a woman hiding in the corners, learning things she is not supposed to. Knowledge is power. These are subversive women.

Or perhaps she was simply gazing from inside at the outside world, because a woman’s place is traditionally in the home.

The TV series Big Love about the three wives of one man offered many opportunities for eavesdropping scenes, as all three women were living in each others’ pockets. When a character is forced to eavesdrop in order to learn what’s going on, this suggests a degree of powerlessness.

In Big Love we never see Bill (the husband) eavesdropping. He doesn’t need to. However subversive the image of the eavesdropping woman, determined to find things out about the world despite the lack of information provided to her, the proliferation of such gendered scenes suggests, to the wrong audience members, that women are naturally sneaky, devious and manipulative.

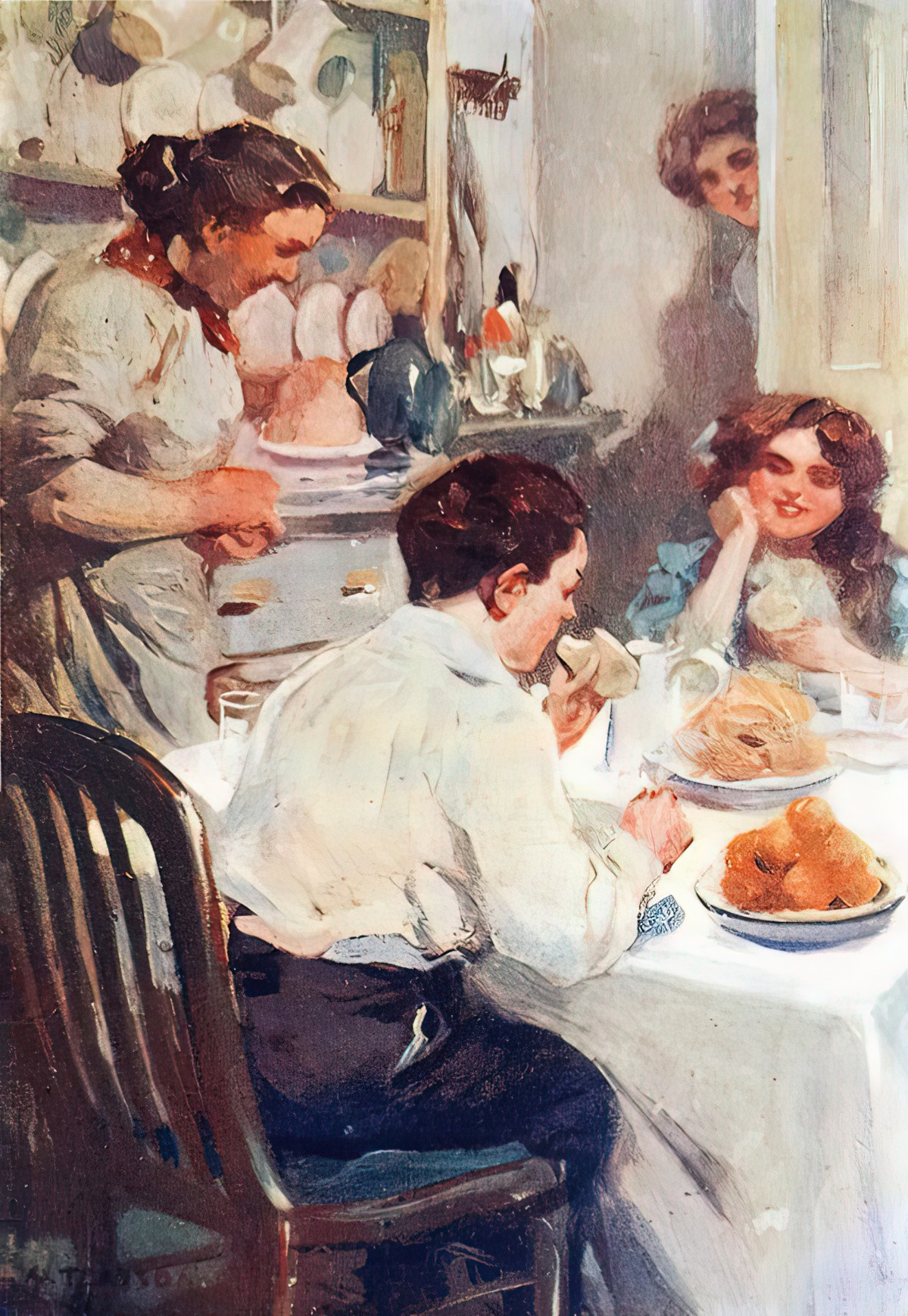

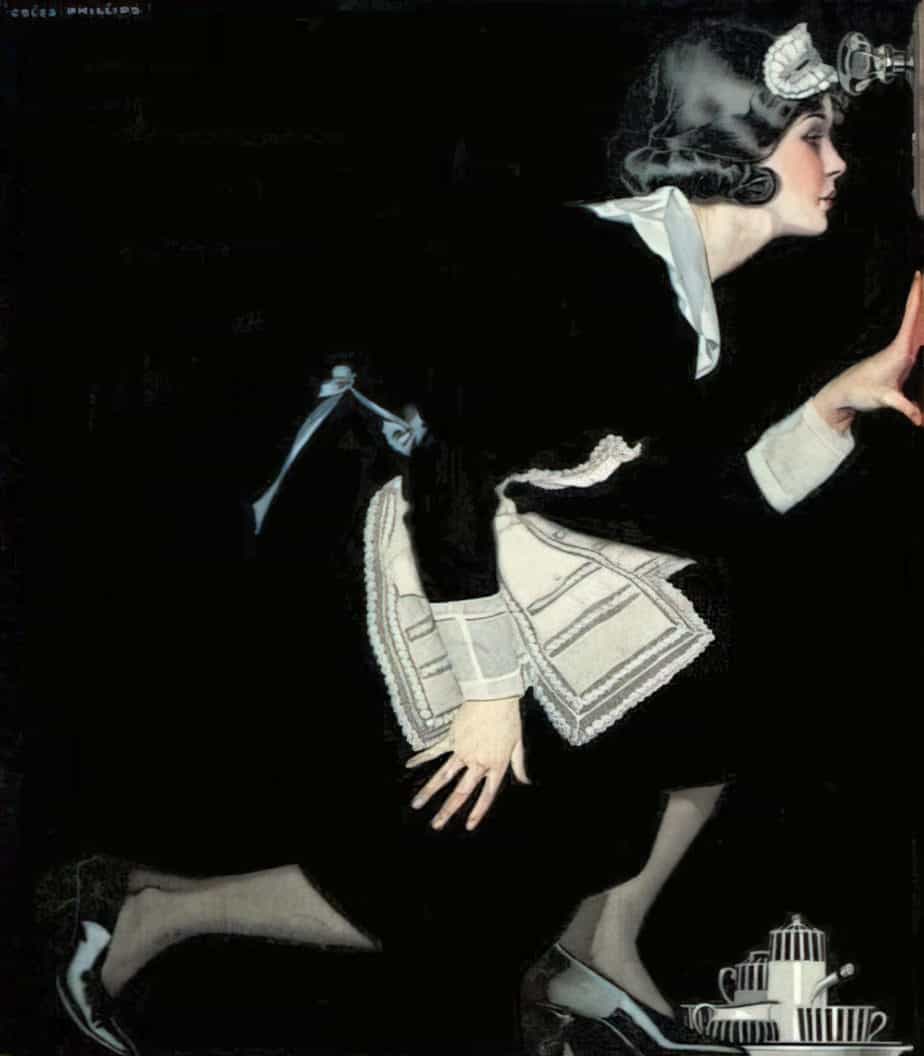

The following image plays on fears of the upper classes about the people they employ to work in their homes.

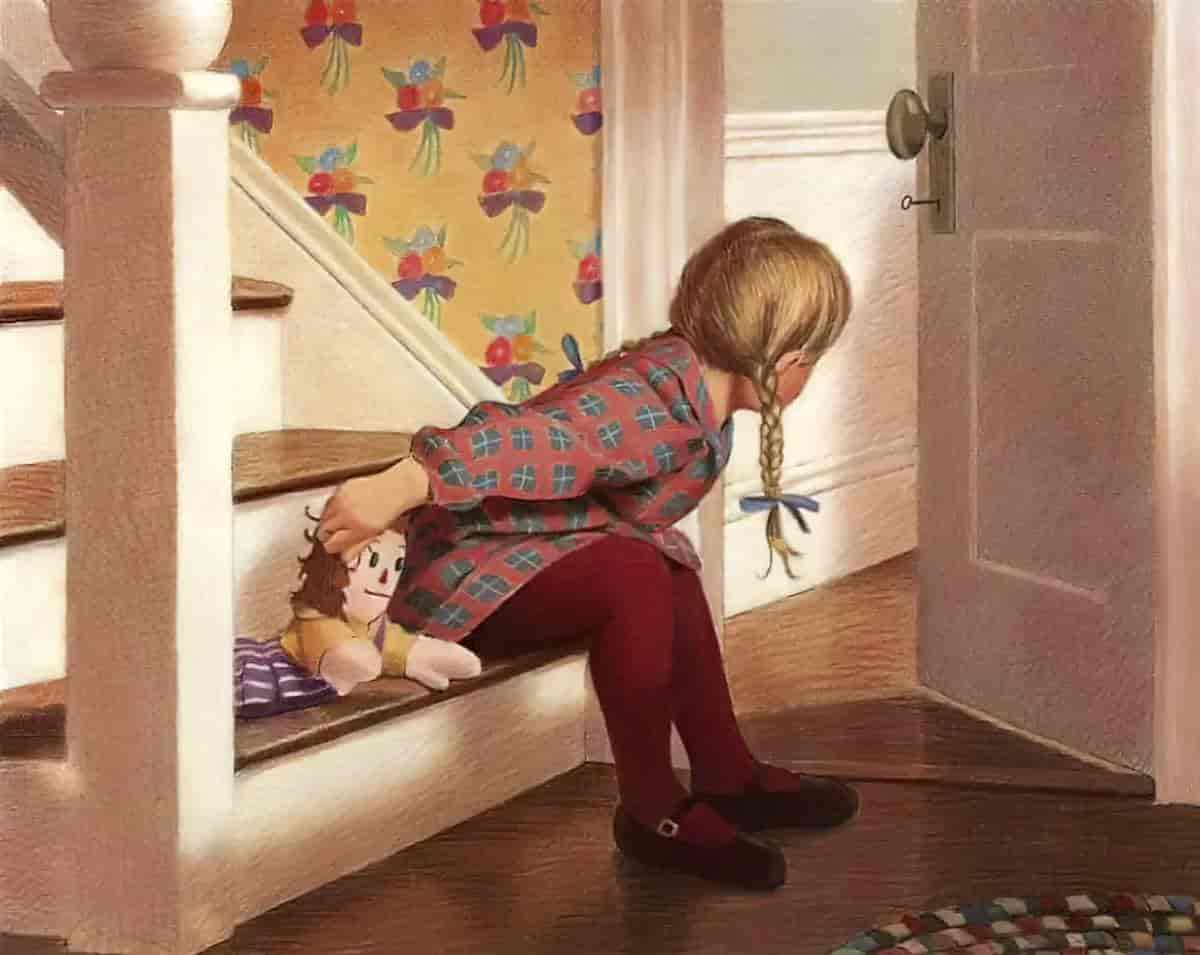

The stairs and hallway are typically a good place in the storybook dream house from which to hear everything going on.

The image below is no doubt supposed to be cute, but there’s something incestuosly creepy about a little brother listening in on his big sister’s conversation with (by her body language) a boyfriend. That same creep factor is utilised in Six Feet Under to unambiguously creepy effect when Billy follows Brenda and Nate into Brenda’s bedroom and photographs them while they are asleep.

The following is an eavesdropping scene from a chocolate box.

Outside ninjas and actual spies, it’s more difficult to find examples of grown men eavesdropping in art. Men run the world. Men don’t need to be secretive about their need to know what’s going on.