“Dump Junk” is a short story by Annie Proulx, included in the Bad Dirt collection (2004). This is a revisioned fairytale based on The Magic Porridge Pot and similar.

Proulx’s shorts stories in many ways allude to, cite, and subvert a number of myths, legends, fairy tales, and folktales converging as common cultural patrimony. Annie Proulx’s short stories in many ways allude to, cite, and subvert a number of myths, legends, fairy tales, and folktales converging as common cultural patrimony.

Benedicte Meilon, The Truth Then Be Thy Dowry: Questions of Inheritance in American Women’s Literature edited by Stephanie Durrans

SETTING OF “DUMP JUNK”

All of these stories are set in Wyoming. Sometimes Proulx makes use of a realworld town, other times she zooms us in as far as the county but invents a fictional town. This is one of those times: Fremont County, Wyoming is a real place (population 40,000); the town of Firecracker appears to be fictional.

The entire county is the size of Vermont, but Vermont has a lot more people packed into it, with a population of 623,000.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “DUMP JUNK”

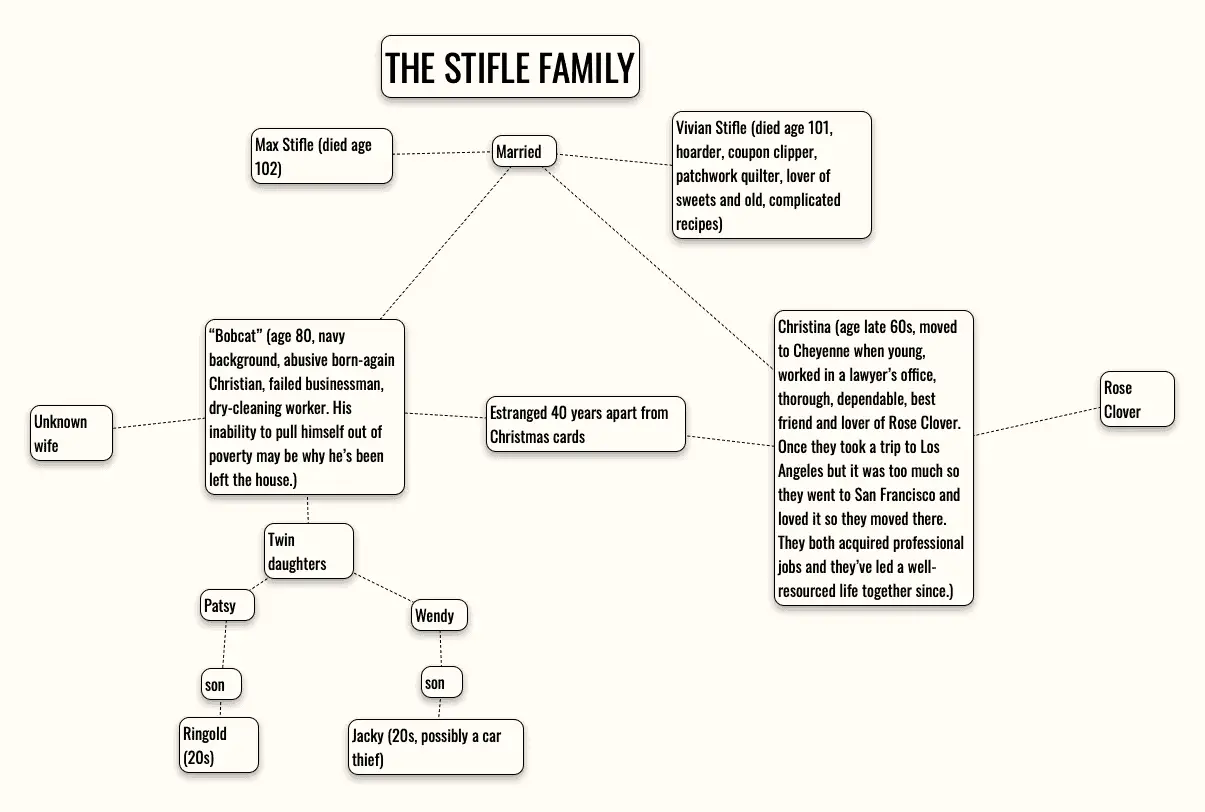

A woman dies and her children sort out her junk. Because the son and daughter don’t get on, the men do the garage and the women sort out the house. In the process, we learn two backstories in particular: the backstory of Max Stifle, and that of Christina, the daughter. We also learn by extension a bit about Vivian, with emphasis on how poverty-stricken they were ‘in the beginning’.

Sorting out a houseful of possessions is a sobering task many adult children must do at some point, and it often (inevitably? always?) reveals something new about the dead parent’s life. No surprise, this life stage is oft mined by storytellers. Stories are about surprise, and the revelation of a secret = excellent surprise.

This plot was used by Robert James Waller in Bridges of Madison County (which Stephen King holds up as an example of bad writing, by the by).

But because this is Annie Proulx, there will be more to “Dump Junk” than the same-old, same-old ‘adult child learns her parent had hidden depths and a sexual side after all’ trope. Sure enough this one takes a turn. In a system of primogeniture, the son, Bobcat inherits the house. Christina, being a daughter, inherits the kettle (her mother’s prized possession) and everything in the house. Since the house is full of junk and the kettle leaks, Christina has inherited nothing.

But “Dump Junk” takes a sudden turn in genre when Christina wishes her parents had invested in a microwave, and then a microwave is noticed, still in its box. She wishes the old jalopy would start outside. She wishes for a vodka and orange—it appears in the fridge.

Proulx is making use of the Rule of Three, in which three times makes a pattern. That’s when the mystery is solved.

Turns out the leaky kettle has magical qualities and can grant wishes. I’ve heard writing advice to the effect of, “Well, if you’re writing fantasy, don’t spring it on the reader. Make sure the reader knows from the first few pages what to expect from the setting.” Implication being: you won’t find the right readers if readers don’t know what genre they’re getting into.

If Proulx ever heard that advice, I doubt she sat up straight. Alongside another fairytale revisioning set on a farm, “The Bunchgrass End Of The World“, this story, “Dump Junk”, starts out as realism. Fairytale magic is sprung upon us with no warning, especially given the story’s place in the rest of the collection.

“Dump Junk” ends in tragedy, because casual wishes work as well as carefully considered ones.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “DUMP JUNK”

“Dump Junk” is a Wyoming re-casting of the Sweet Porridge category of fairytales, in which a receptacle grants the wish of excess in a time of poverty. (I took a close look at The Magic Porridge Pot in this post.) Such tales are classified by Aarne-Thompson as 565.

This category of tale can be seen across time and across cultures. It starts out as a wish fulfilment fantasy but the rule is that it ends with a moral lesson about greed. China gave us stories about a boy with a magic brush, who could paint anything. These are similar. In that case, the boy uses the brush to conquer someone else’s greed. (The Magical Life Of Mr Renny is a picture book riff on that classic tale.)

Annie Proulx isn’t into moral lessons. In contrast, she’s known as a ‘fatalistic’ writer. The term ‘geographical determinism’ is often used. “It is what it is. Doesn’t matter what you do, you’re a product of your time and place.”

At first a fairytale plot seems to fly in the face of fatalism. If some people have access to a genie, doesn’t that mean they’ve taken control of their poverty-stricken fate? On reflection, this sort of fairytale is exactly in line with Proulx’s world view. Across her stories humans behave in predictable ways, shaped by whatever is available to us in our environment. Access to wealth doesn’t necessarily help people rise up. We’re all at the mercy of some power greater than ourselves, though not in the religious sense. Instead, Proulx makes use of vast geography to turn humans into highly fallible miniatures.

I like stories with three generations visible. Geography, geology, climate, weather, the deep past, immediate events, shape the characters and partly determines what happens to them… The characters in my novels pick their ways through the chaos of change. The present is always pasted on layers of the past.

Annie Proulx

In “Dump Junk” Proulx makes use of not three but four generations to emphasise the minuscule length of a single human life.

SHORTCOMING

The Stifles are a family with major, long-standing internal problems.

Proulx describes Bobcat and Christina’s relationship in a matter-of-fact way, but any man who strangles women in arguments needs to be taken seriously. Strangulation is the most reliable precursor to subsequent murder. Not only that, strangulation (without loss of life) very often results in lifelong injury to the throat area. This is why some governments have started to take choking seriously. New Zealand instituted a new non-fatal strangulation offence specifically around choking and suffocation, and the offence can now carry seven years’ imprisonment.

Bobcat has probably inherited these attitudes from his father, who spent much of his life in the ‘caring’ profession of teaching, but garnered a reputation for maimed hands among the boys he taught shop to. Bobcat remembers his father for his criticisms. Terrible things happened in his classes while Max Stifle was in the toilet, when he should’ve been supervising his unruly students.

The first thing that strikes me about this family is how unusual it is that Max and Vivian lived so long. Most times, only people with money and education make it to over 100. Sixties and seventies is a more common period in which to die. In hindsight, of course, we can deduce that Max and Vivian made the decision to live til 100 each. It took them a further year or two to actually decide to die.

DESIRE

Bobcat and Christina want to clean up their parents’ house as quickly as possible and hightail on out of there. But when the mystery develops, of course Christina wants to find out the truth.

OPPONENT

It helps story conflict that Bobcat and Christina dislike each other a lot. But opposition usually works best if it’s more complicated than simple, long-standing animosity. If there’s no big, outside opposition (e.g. a natural disaster, a supernatural monster), it’s a good idea to introduce a mystery. Then, the mystery functions as opposition.

The mystery here: Why did Vivian Stifle live as long as she did, but suddenly stop doing a lot of the things she used to do? The women can tell exactly when she stopped collecting bags, when she stopped collecting recipes.

Patsy pulled a grocery receipt from one of the sacks on top of the pile. “Actually I think she stopped somewhere along the line. Look at the date – it’s 1954. She must have stopped back then.” She pulled out a sack near the bottom and found a handwritten grocery slip for a hundred pounds each of flour and sugar dated 1924. The amount paid was small as there was a notation that she had brought in six dozen fresh eggs to trade against her purchases.

Out in the shed, their son wonders how Max and Vivian managed to live when they had nothing to live on? He goes through the possibilities. Did they inherit from somewhere? Do they have a secret stash?

PLAN

The initial plan is to divide by gender and get the house and garage sorted quickly.

When Christina discovers the iron teakettle is magic, she tests it out. Then she uses it knowingly.

BIG STRUGGLE

Which is the Battle scene? Sometimes it’s not obvious. And I don’t think it’s obvious here, but whatever it is, it’ll be the bit that comes right before the Anagnorisis. Even this isn’t always easy, because in a story like this, who’s the star?

I believe the “Battle” is the low-key scene in which Christina takes the kettle out to her brother. She’s about to tell him what it can do, but he speaks to her harshly and she suddenly changes her mind. Bobcat has unwittingly lost a big struggle that really never got started.

ANAGNORISIS

Annie Proulx quite often keeps anagnorises from her characters, who keep on keeping on, stuck in a rut, along their fatal paths. But she does makes sure to offer the reader a revelation, and mine comes after this:

Bobcat had had a prostatectomy three years earlier, and the perineal incision had cut both bundles of nerves. He had not had an erection since the operation and was still wearing diaper pads for the accompanying incontinence. Although he was glad to be alive, his condition made him irritable and short-tempered. The sight of his two grandsons, healthy and big, jumping around and talking about cars and girls and music, punished him severely. At the same time he felt pity for them, wanted to warn them that the hard years were coming and their entanglement of emotional and money problems, vexing questions about the cosmos, the hereafter, the right way of things, and then the slow, wretched betrayals of the flesh.

On the surface, Bobcat was responsible for the boys’ death, by arguing that they deserved the old cars, despite them being unsafe. But with this paragraph, and the way Proulx creates a brief “Overview Effect” by taking us up into the cosmos, tells us that Bobcat has unwittingly wished evil upon his grandsons, but indirectly. His envy of youth and his mapping his own old age onto theirs is so silently powerful that the iron teakettle hears him anyway. Christina has possibly involved Bobcat’s wishes by taking it out to him as he worked in the garage.

Apart from this revelation, there’s a twist in the plot of the tale. When Christina wishes her brother dead, she kills an illegitimate brother nobody knew of until now.

NEW SITUATION

Christina has the kettle and she alone knows what it can do. No one else has worked it out. So we can safely extrapolate that she’ll use it, not always wisely, and that her other brother is soon for the scrap heap. But before he goes, he is unwittingly causing harm via his own bad feelings.

TAKEAWAY TIPS FOR WRITERS

- Study “Dump Junk” if you would like to insert some magic, but you would also like to start out writing a realistic setting. In other words, if you want to keep the fairytale element as a reveal.

- Because of the big revelation that this story includes magic, it reads quite differently the second time round. We deduce, in hindsight, where Vivian got Christina’s three new dresses from. But even in minor descriptions, knowing hindsight changes the meaning. The ‘strapping hulks’ of great-grandsons is sadly ironic given that they’ve been killed because they weren’t strapped into their car seats.

- As Proulx describes the junk-strewn house, we get a very clear image of the entire property in a few deft paragraphs. I definitely get the feeling Proulx has done her own large-magnitude clean-up job.

The old lady had gone in for jars, fabric scraps, and old clothing that might be used in a quilt, and, of course, recipes. She was a tireless clipper of recipes for Golden Raisin Hermits, Devil’s Food cake, pickles, leftovers masquerading under such names as “Pigs in Potatoes” (leftover sausages and cold mashed potatoes), “Roman Holiday” (leftover spaghetti with chopped string beans), “Salmon Loaf” (canned salmon, more leftover spaghetti). For decades Vivian Stifle had pasted the recipes in notebooks, account boos, novels, and books of instruction, each collection dated on the flyleaf. There were dozens of them lined up in the parlor glass-fronted bookcase. The recipes disclosed that the Stifles’ diet was dominated by a sweet tooth of enormous proportion. The old lady must have used ten pounds of sugar a week on chocolate cream pie, “Filled Cookies from Oklahoma,” and cream cake. She made her own maraschino cherries, too, and ketchup, the old kind of mincemeat that called for chopped beef, suet, and leftover pickles juice steeped in a crock – food that nobody now knew how to make. Still, the corporate food purveyors had been making headway, for many of the recipes featured Crisco, Borden evaporated milk, Kingsford cornstarch, and other mass-produced foodstuffs. Sometime in the 1950s she had stopped collecting recipes. The last book on the shelf was dated 1955, and there were only a few recipes pasted onto the pages of a Reader’s Digest condensed book.

The detail of rat droppings in the bags really resonates, because that’s exactly what you find when you’re cleaning them out after a rat or a mouse infestation.

“There are just hundreds! Now I save some of the plastic bags, but these – they’re all mouse droppings and dust.” The paper bags stuck to one another in great chunks as though they were trying to return to their earliest incarnation as trees.

“Watch out, Aunt Christina, you can get hantavirus messing with mouse droppings.”

“Dump Junk” is a masterful example of a fairytale revisioning. Proulx has borrowed fairy magic and used ‘the granting of wishes’ as a metaphor for ‘the passing down of intergenerational violence’. Bad feelings travel down. The overall message becomes: A history of poverty and family violence doesn’t just stop in its tracks, even if subsequent generations ostensibly haul themselves out of it, due to living through more prosperous modern times.