Don’t forget that dragons are only guardians of treasures and one fights them for what they keep – not for themselves…

Katherine Mansfield

Dragons In Folklore

Dragons have always evoked a mixture of fear and attraction.

They’re everywhere in The Bestiaries.

Folkloric dragons always talk. They are semi-human and have wily intelligence. Sometimes they’re regal, sometimes cowardly.

In Chinese/Taiwanese culture, the dragon is the best animal: wise, benevolent, powerful, but peaceful. Any story in which a dragon is killed is automatically a tragedy.

Henry Lien

Dragons Around The World

Alexandra the Rock-eater: An Old Rumanian Tale retold by Dorothy Van Woerkom (1978)

An underdog main character convinces a dragon of her own considerable might. This is a familiar device. (For example, you might squeeze cheese but persuade a formidable opponent that you’re really squeezing buttermilk from a stone.) She’s trying to get rid of the local dragon in return for a gift of animals. She needs animals because she has 100 children to feed (all magic results from having wished for them.)

The same device of tricking a formidable creature into thinking you’re much stronger than you are is used by Julia Donaldson in The Gruffalo.

Eastern dragons are magical, influence the weather, are godlike and maternal. Sometimes they’re wizards in disguise.

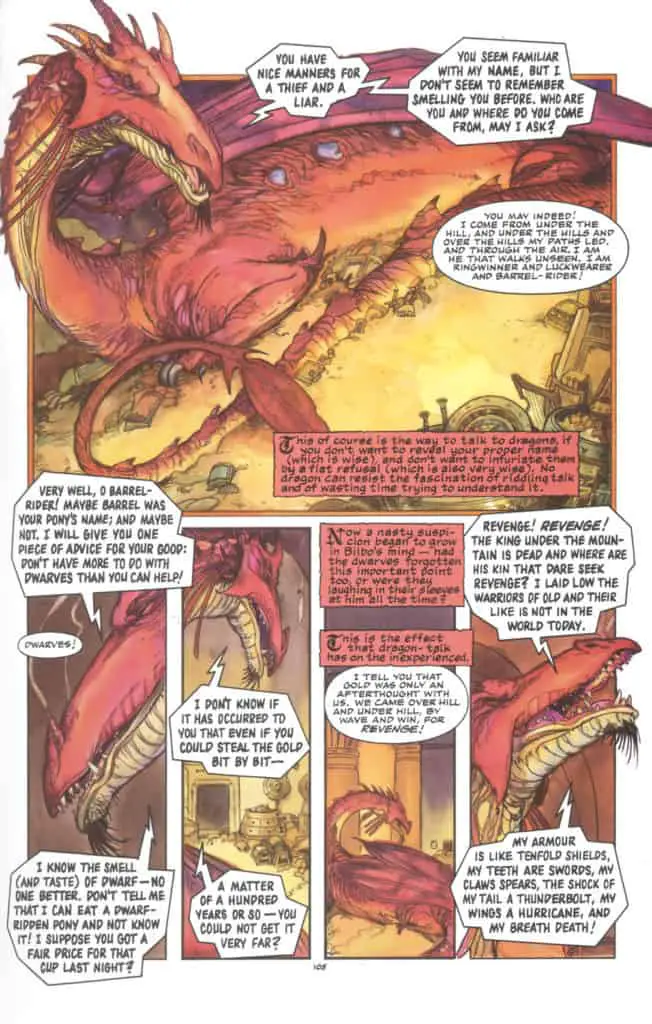

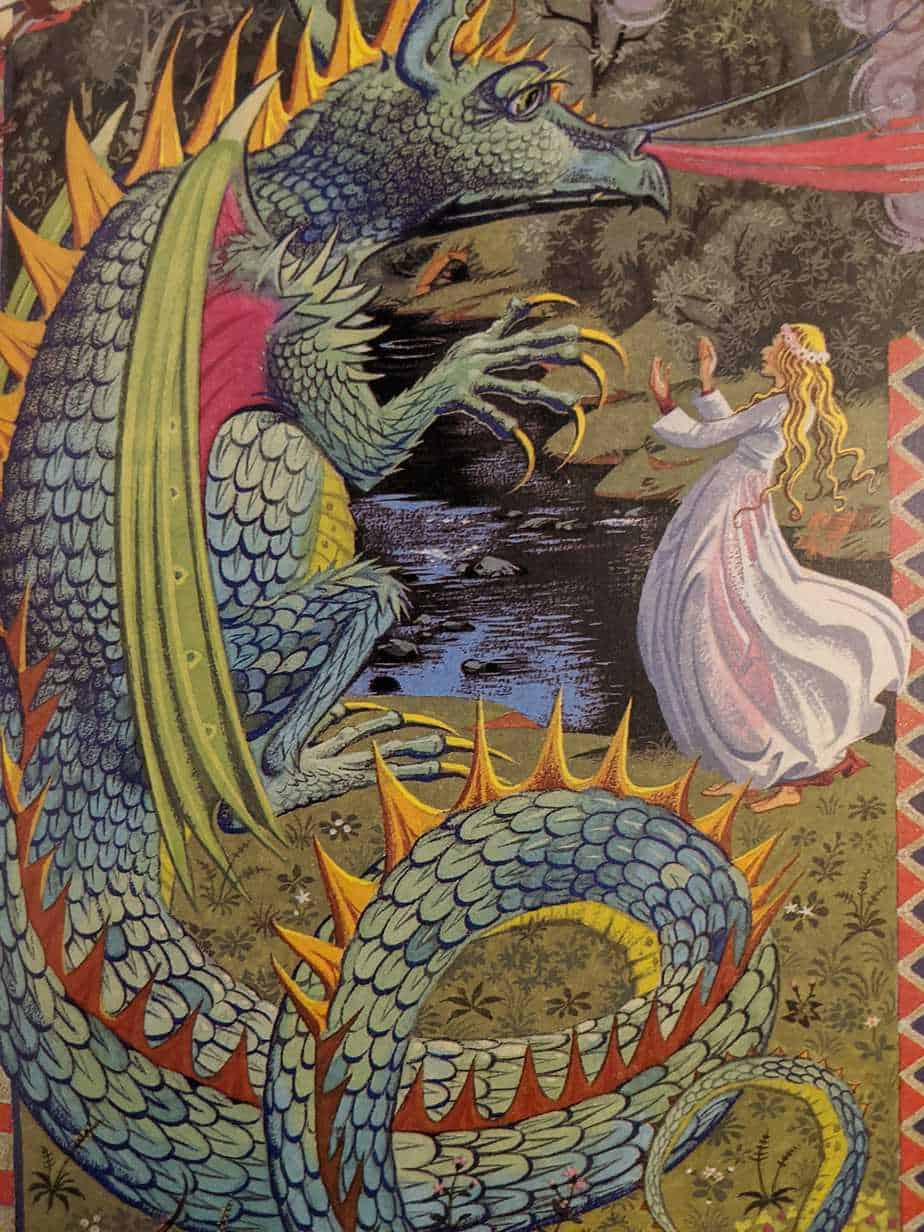

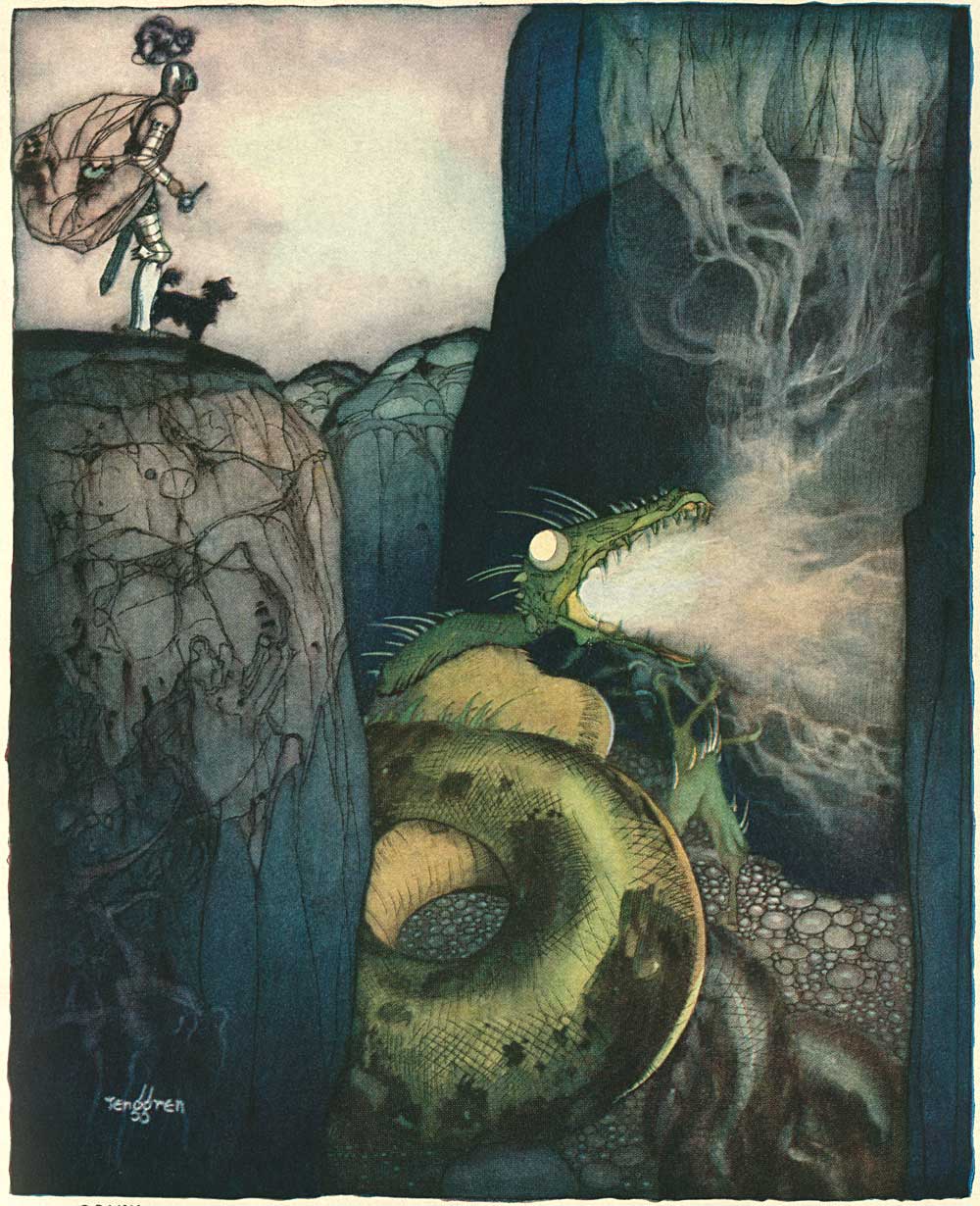

Northern dragons love jewels. They have fiery or poisonous breath. They’re often curiously merry or sardonic because they consider themselves invincible. But they can be beaten or more often outwitted via some weak spot. They’re long-lived, unhappy and their hoarded wealth brings them no joy.

Beowulf and Sigurd The Dragonslayer gain nothing except fame from their dragon conquests. Eustace Scrubb (Chronicles of Narnia) and Bilbo Baggins (Lord of the Rings) also found out that it’s best to keep one’s mitts off a dragon’s things. It’s easier for a modern audience to identify with the likes of Scrubb and Bilbo rather than Bewulf; Bilbo is just like us, only a little more determined, which is a great recipe for a popular hero.

In Britain, dragons are associated with Cornwall. See King Arthur.

Dragons And The Quest Story

Stories about dragons are traditionally about the men who defeat the dragons, in your archetypal Quest Story. (The hero is always a man.)

There are a few ways of inverting that trope.

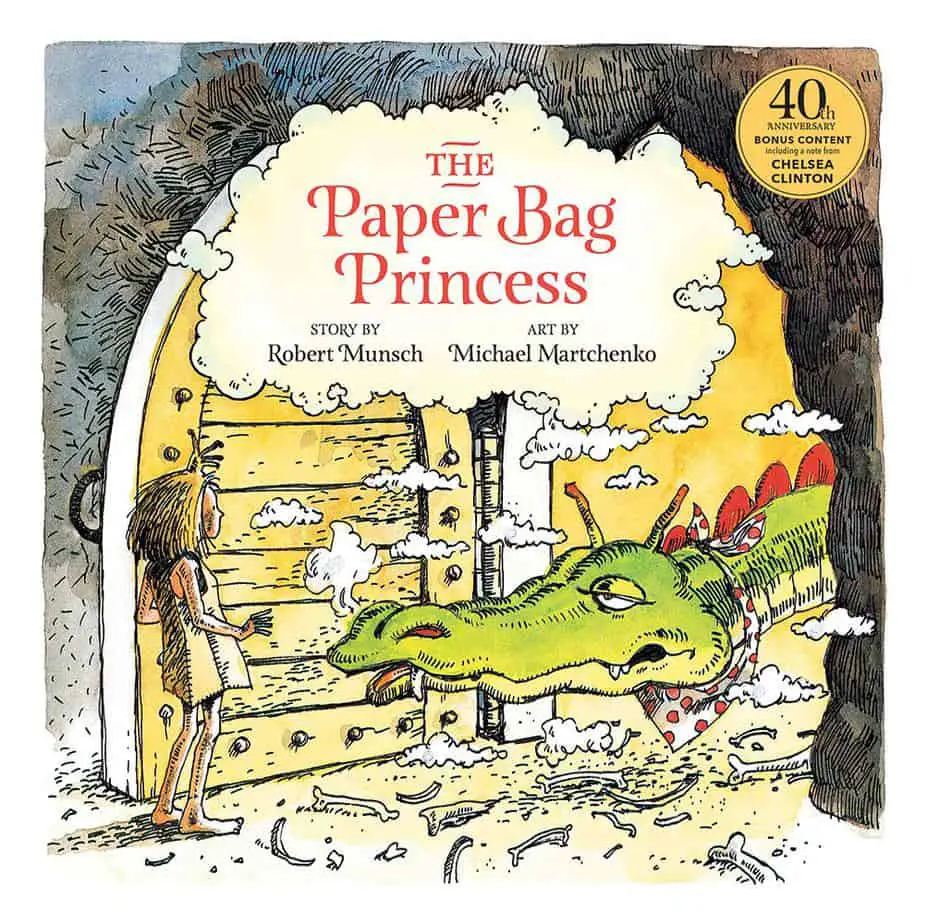

1. You can make the hero a girl. (Preferably very small and cute — the human equivalent of a mouse.)

Trouble With Dragons by Oliver G. Selfridge and Shirley Hughes (1978)

Here’s an old routine in storytelling:

- A prince comes

- Prince falls in love with princess

- Prince goes off to earn her hand in marriage

- Prince is eaten by dragon.

But in Selfridge and Hughes’s retelling the gender is inverted. This book is now hard to find, but Babette Cole has done a very similar thing in Princess Smartypants, though it’s not so morbid. In Selfridge’s story two of the sisters die. The picturebook buying public don’t tend to go for that.

2. Either that, or the dragon is not actually scary at all, perhaps denatured in some way: weak, small, friendly.

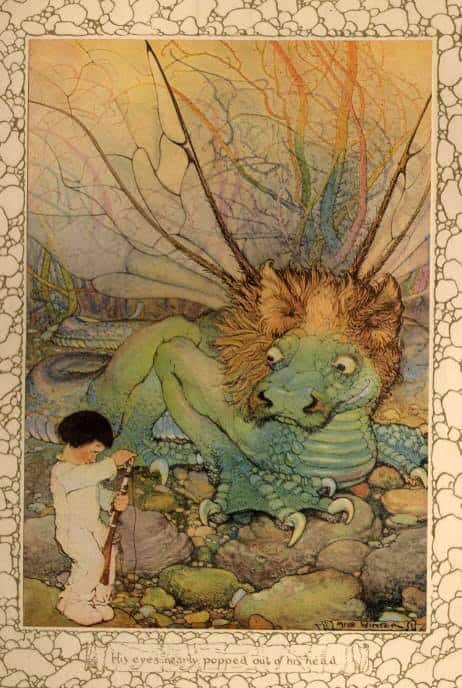

We see these kinds of dragons in modern children’s literature. Kenneth Grahame was the inventor of this kind of benign dragon in The Reluctant Dragon (1899). His was the first dragon humans could live alongside. Grahame’s dragon is the trope of an Edwardian dilettante who likes company and composing verse. He leaves fighting to all the other dragons.

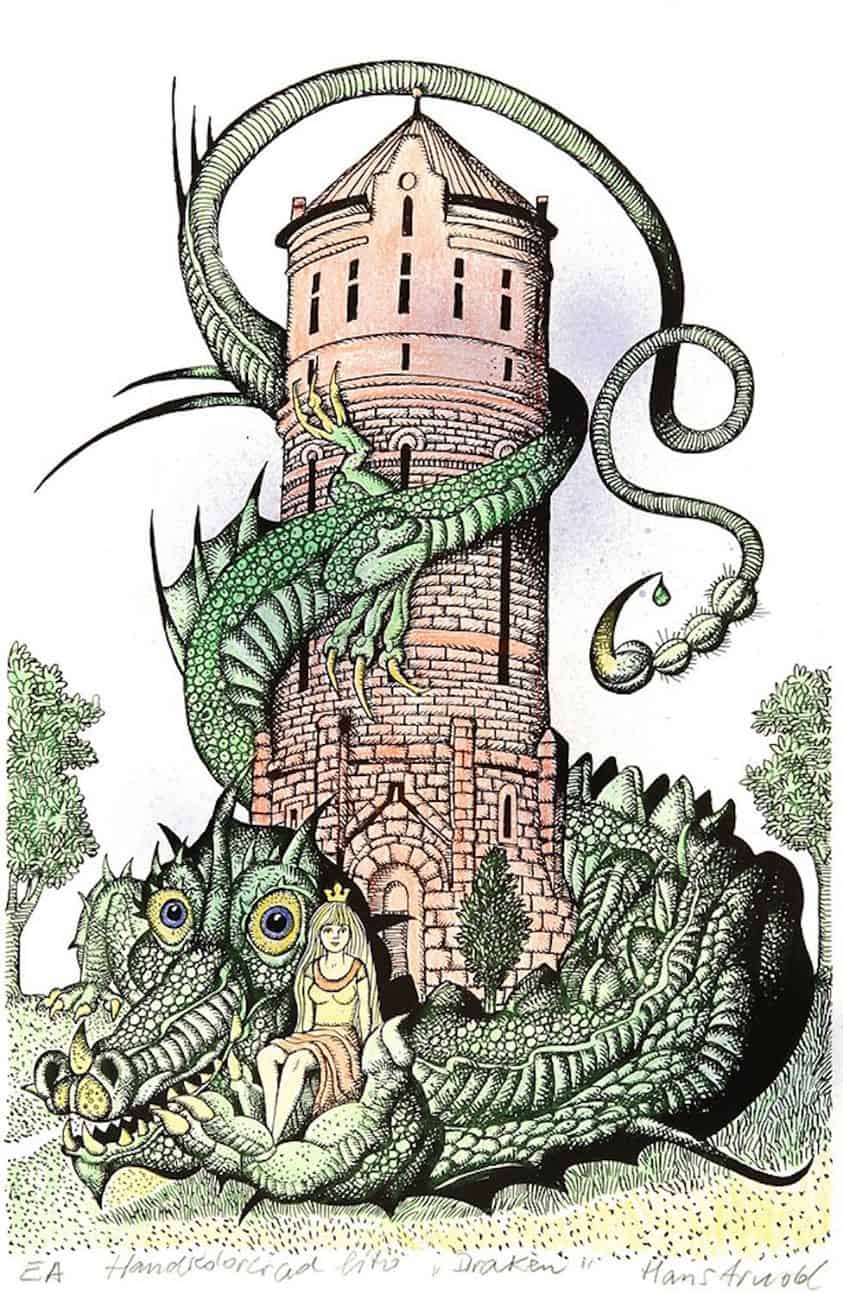

Dragons and Castles

There are certain things one expects to find when we encounter castles in stories:

- Heroes

- Fair ladies

- Bats in belfries

- Four-poster beds

- Servants and attendants

- Moats

- Drawbridges

- Frogs on lily pads

- Bows and arrows

- Dragons

Books for children such as Creepy Castle by John S. Goodall make use of all of these things, often to comic effect. Experienced readers know that a comedy set in a gothic setting is ironic, and it therefore holds more interest.

Dragons In Human Form

When describing humans, dragon is a gendered term. Human dragons are often aunts, in children’s literature. Why? The aunt is often a maiden as well. In traditional society this means that she cannot have children, and the societal pressure on women to have children is so strong that it is assumed when a woman does not have children than she must therefore not like them. Hence, she is a dragon.

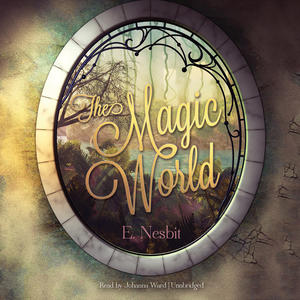

In The Aunt and Annabel, a short story from E. Nesbit’s collection The Magic World, a child is isolated in a room as punishment for having tried — and failed — to do an adult a good turn. The aunt is a grim, misunderstanding tyrant and the child is an innocent little saint.

A canine version of this dragon aunt trope is also used in Wolves of the Beyond: Lone Wolf, in which the story opens with a slightly deformed pup being born into a clan who takes such pups away and abandons them, to die alone. The job of dispatching is left to an infertile female wolf. It’s impossible to consider this fictional wolf clan in isolation, without considering how child free women are treated in human societies:

The Obea was the female wolf in each clan designated to carry deformed pups out of the whelping den to a place of abandonment. Only barren she-wolves were eligible, since such wolves were assumed not to have developed maternal instincts. With no blood offspring, Obeas were devoted entirely to the well-being of the clan, which could not be healthy and strong if defective wolves were born into it. The rules were precise. The deformed or sick pup was to be removed by the Obea and carried to a remote spot where it would be left to die of starvation or be eaten by another animal.

Wolves of the Beyond: Lone Wolf by Kathryn Lasky

By the end of Lord of the Flies, Roger becomes the dragon to Jack, with shades of Dragon-in-Chief and Dragon with an Agenda.

The Hunger Games: Clove to Cato

Luke Castellan to Kronos in Percy Jackson and the Olympians.

In Eclipse (Twilight series) Victoria uses Riley as her dragon and also has him making all of the moves for her.

Dragons And Weather

In Colie Thiele’s book February Dragon (1976), the threat of an Australian bush fire is the “dragon” of February. In this story, the Pine family and neighbours lose their farm, crops, home and most of their pets.

But in this book, too, the human dragon is the Aunt, who indeed is the one to accidentally start the fire while on a picnic. Like the mythical Northern dragon, it is Aunt Hester’s arrogance that is the cause of the downfall.

Dragons As General Villain

Henry Allen’s dog is missing – and he thinks it’s been eaten by a dragon! On the night the dog disappeared, Mr. Allen swears he saw a huge dragon slither into the sea caves beneath his cliff-top house. Could Mr. Allen really have seen a dragon? The Three Investigators doubt it, but they’re determined to find the missing dog. That means exploring those dark, dangerous caves.

And whether or not Mr. Allen’s dragon is real, something terrifying and deadly is lurking there!

Dragons In Other Form

In Mrs Frisby And The Rats Of Nimh, the Fitzgibbon’s cat acts as the dragon to the various animals on the farm, terrorizing and killing many of them including Jonathan, Mrs. Frisby’s husband. The cat is quite appropriately named Dragon.

The only dragon in Narnia is actually a boy who has been turned into a dragon. But he has a human soul.

Denatured Dragons

Dragons became much more tame with the advent of Christianity, and they’ve been getting tamer and tamer since, with a few exceptions.

In picture books, which are most often read right before bed, dragons tend to be benign inversions of the mythical, fearsome monster. For example, in There’s No Such Thing As A Dragon by Jack Kent (1975), the dragon beams and wags its tail and loves to cuddle.

These cutesy dragons have been around for a while. They seem to be variations on the boy/dog buddy story, in which the dragon is a companion much like a beloved pet dog would be.

In 1937 there was My Friend Mr Leakey in which the dragon was a dangerous but comical dog.

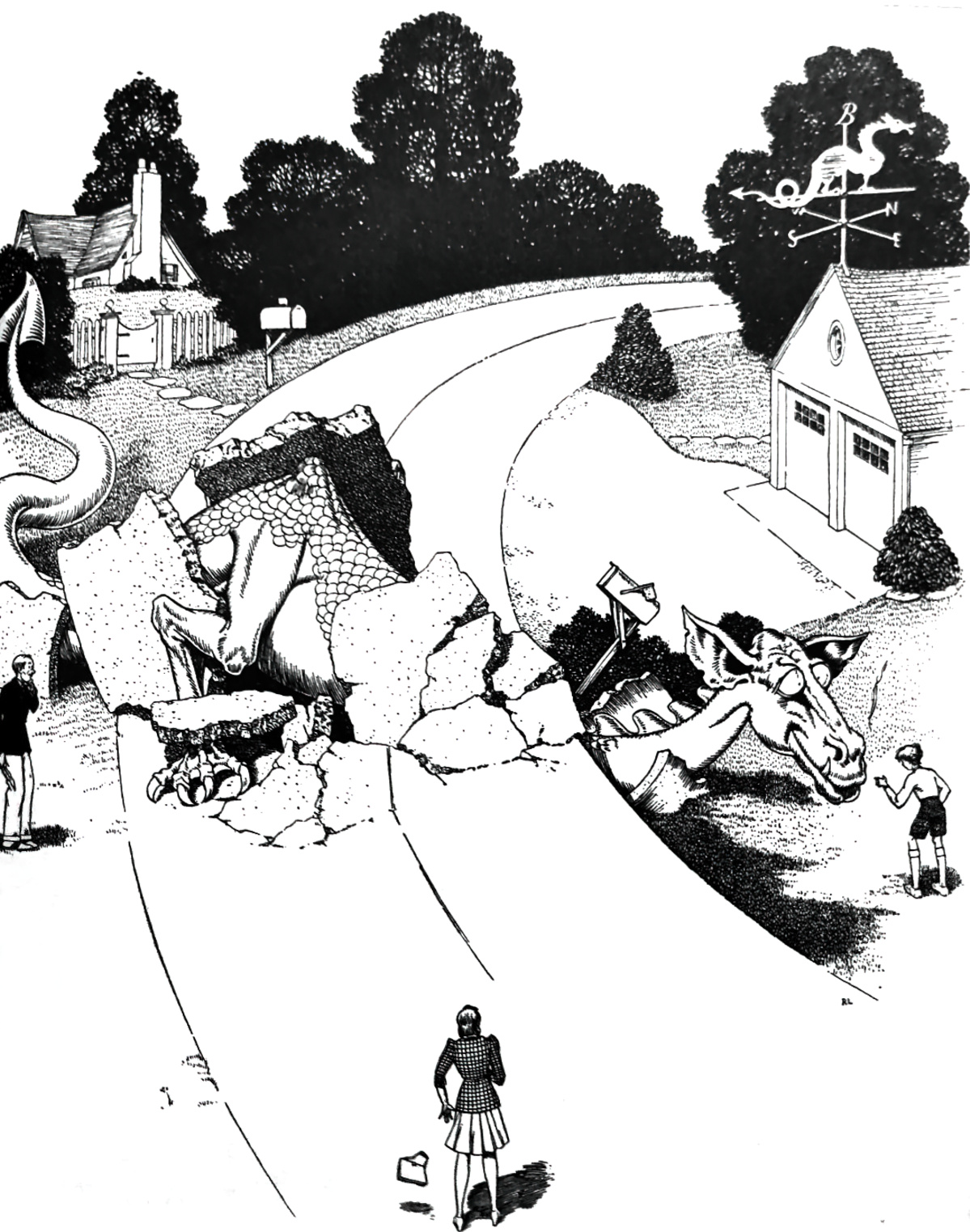

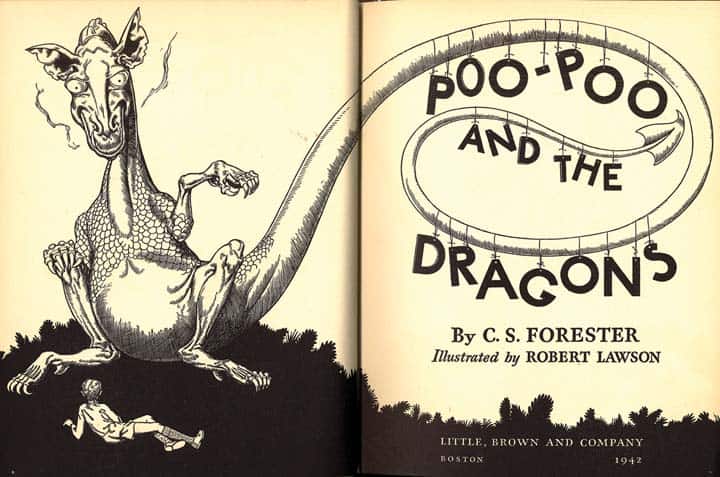

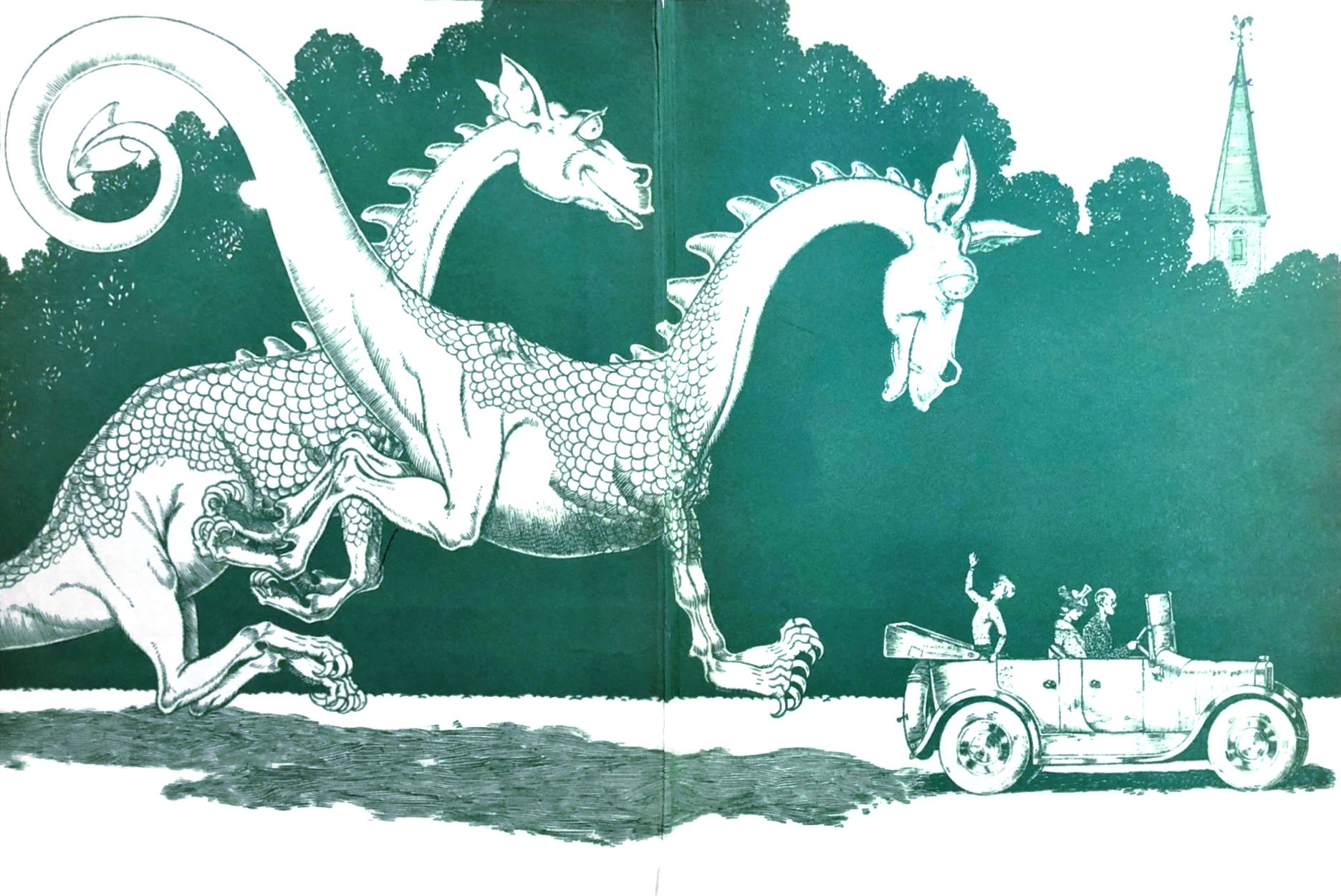

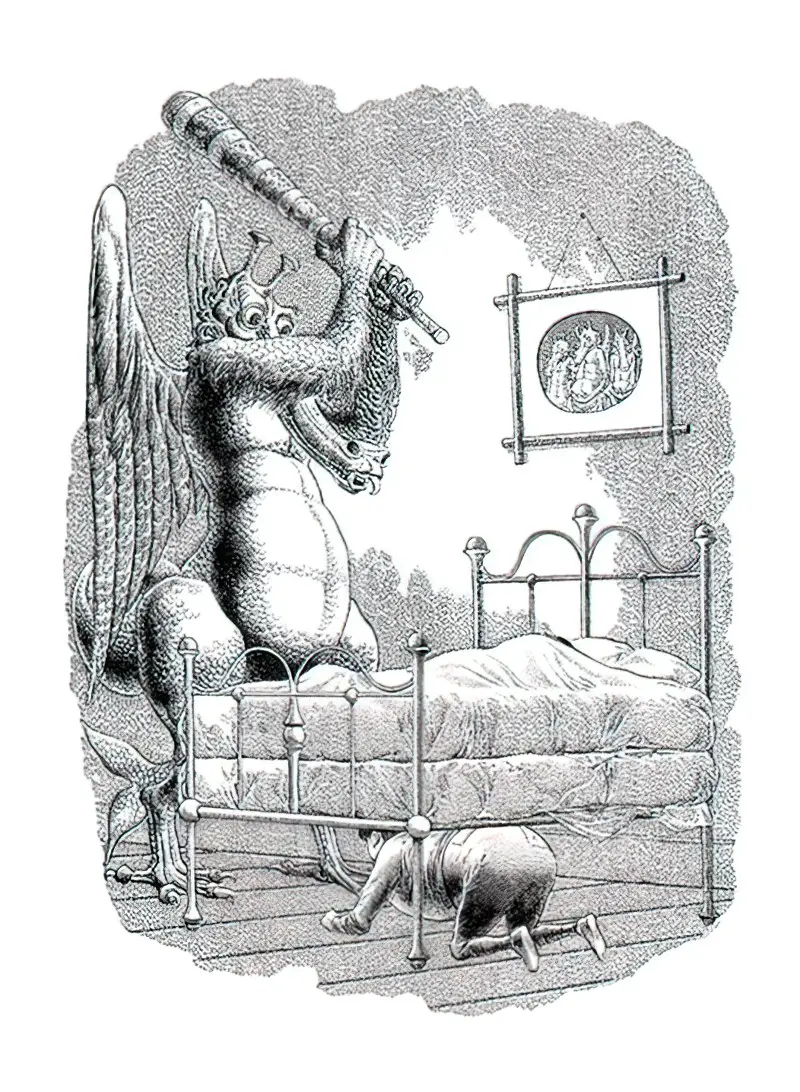

Poo Poo And The Dragons by C.S. Forester was published in 1942, illustrated by Robert Lawson. Interestingly, there weren’t many of these types of stories published between the wars, but they came back afterwards. In this story, Harold Heaviside Brown meets his dragons by the simple but perfect method of ‘wandering up’ inside one of the fuchsia flowers on a bush in the garden. Inside he finds a dragon on a vacant piece of land. Doglike, it follows him home, wagging its tail, squirming and wriggling. Later, it brings a friend and they both make themselves useful, mowing the lawn, polishing the floor, and laughing at jokes.

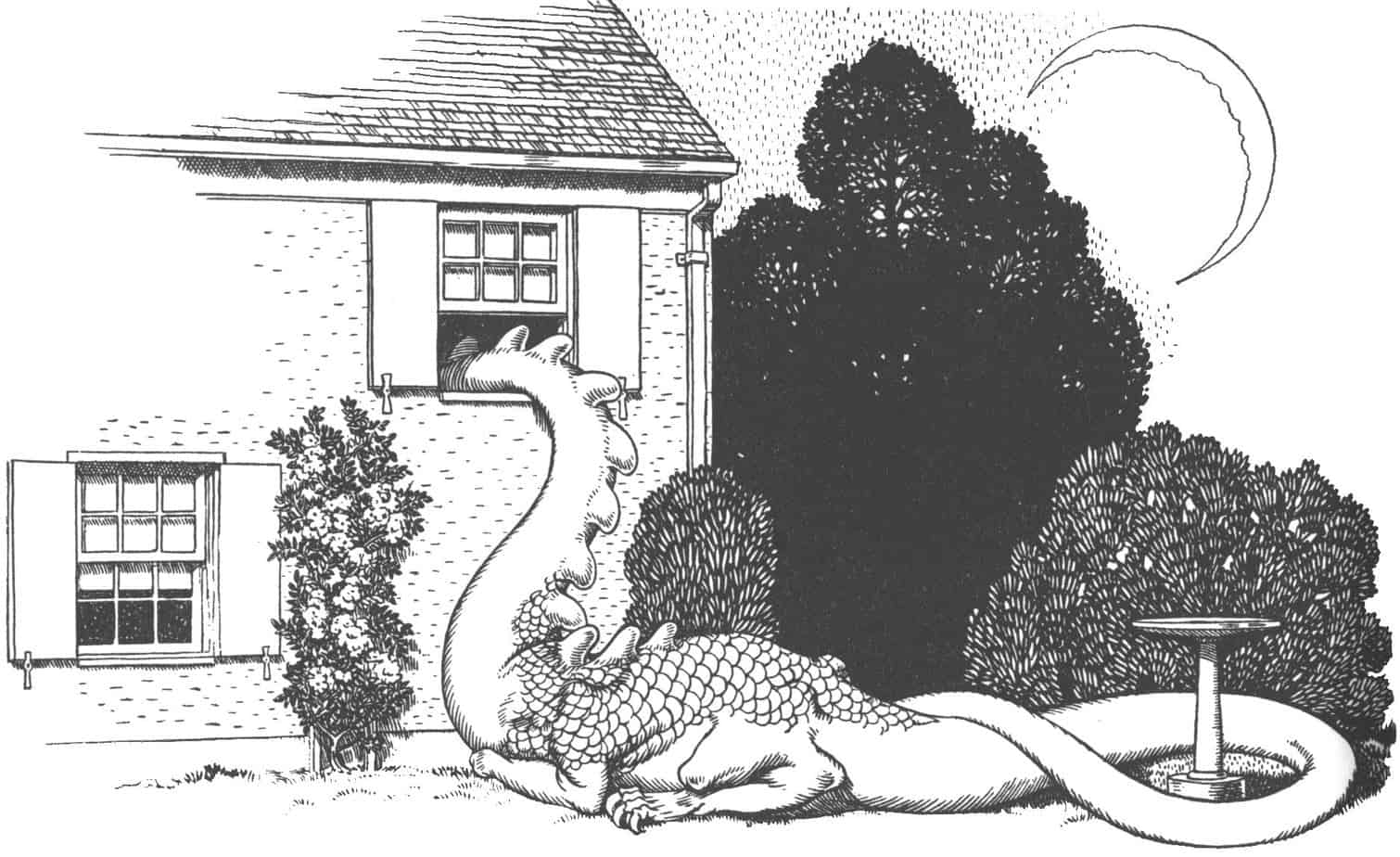

They sleep in the garden with their heads in Harold’s bedroom.

Another, modern, story featuring a creature that can’t fit into a boy’s bedroom is the whale in Billy Twitters and His Blue Whale Problem by Mac Barnett and Adam Rex.

The story structure of Poo Poo reminds me a lot of Enid Blyton’s The Wishing Chair books, in which a pixie called Chinky (like Poo-Poo, another cutesy name) lives in the playroom at the bottom of the garden (where adults won’t notice him). In both stories the child and mythical creature companions go off on various adventures together. In both stories, the garden features heavily. Harold Heaviside gets into the magic world via that fuchsia. The dragons go to school with him during the day, however, and comedy comes out of the dragons needing to learn to read and write. Like pet dogs, they have recognisable but simplified emotions: joy, disappointment, laughter, tears. They are accepted by the neighbours but are a bit of a nuisance.

Rosemary Weir’s Albert The Dragon (1973) lives in Cornwall, but apart from that he’s nothing like a traditional dragon. He’s even vegetarian and likes seaweed. He’s also helpful around the house. His psychological shortcoming is that he is lonely. Taking in an ungrateful baby centaur is meant to help with that, and leads to many adventures. It’s not an especially successful plot, and is now out of print.

Dragons In Modern Children’s Literature

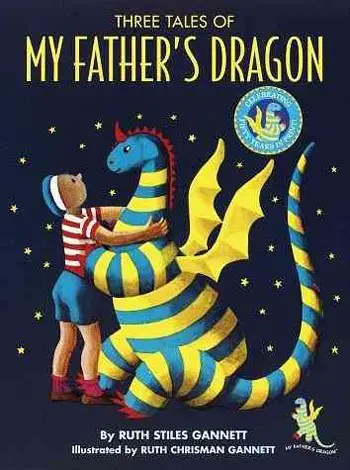

This fantastical, whimsical series about the very resourceful Elmer Elevator, who sets off to rescue a baby dragon after a stray cat suggests it, was one of our favourites as children. Plus, it has the reboot built right in — all the stories are about the narrator’s father’s dragon, but maybe it’s time for him to find one for himself. On to Blueland!

Flavorwire

Some of the best selling kid lit over the past few decades has featured dragons.

- We have Lord Voldemort’s dragons in the Harry Potter series, among others.

- There’s the humanised dragon relationship in Twilight, mentioned above.

- The Spiderwick Chronicles has its own Bestiary.

- How To Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell is very popular.

It’s safe to say, dragons are here to stay.

FURTHER READING

The Dragon, the Mountain, and the Nations

People have long been captivated by stories of dragons. Myths related to dragon slaying can be found across many civilizations around the world, even among the most ancient cultures including ancient Israel. In his book The Dragon, the Mountain, and the Nations, Robert Miller chronicles the trajectories and transformations of this myth, and brings out the major role of dragon slaying in both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. Join us as we talk with Robert Miller about an age-old, fascinating topic: dragons! Robert D. Miller II earned his Ph.D. in Hebrew Bible from the University of Michigan, and is Associate Professor of Old Testament at The Catholic University of America, and Research Associate with University of Pretoria, South Africa. His other books include Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the 12th and 11th Centuries BC (2005), Oral Tradition in Ancient Israel (2011), and Covenant and Grace in the Old Testament: Assyrian Propaganda and Israelite Faith (2012). Robert teaches courses in Old Testament, the ancient Near East, and Archaeology.

New Books Network

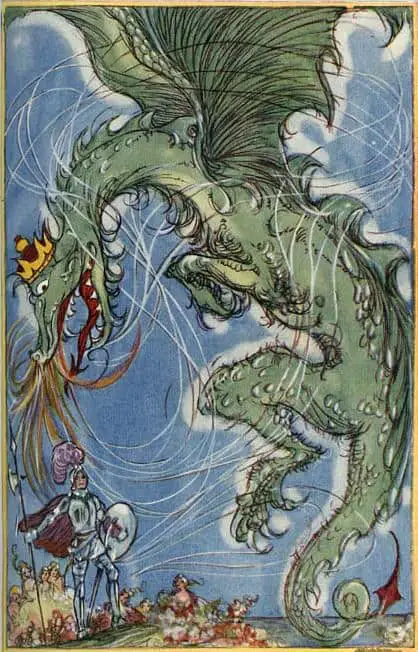

Header painting: Odilon Redon (France, 1840 -1916), Roger and Angelique (Saint George and the Dragon or Andromeda saved), after 1908, oil on canvas