Donnie Darko is a 2001 film set in 1988, in a fictional Virginia town called Middlesex. This genre blend of drama, mystery and science fiction is precisely ambiguous enough to generate much discussion about what is meant to have happened. This is ideal ‘cult-following’ material. Note that Donnie Darko didn’t make much of a splash when first released, but achieved its cult following subsequently.

Today I offer my own take on What Happens in Donnie Darko — nothing that hasn’t been said before — but I’ll also come at it from a storytelling point of view. What makes Donnie Darko a satisfying story? Why do viewers who love this film really really love it?

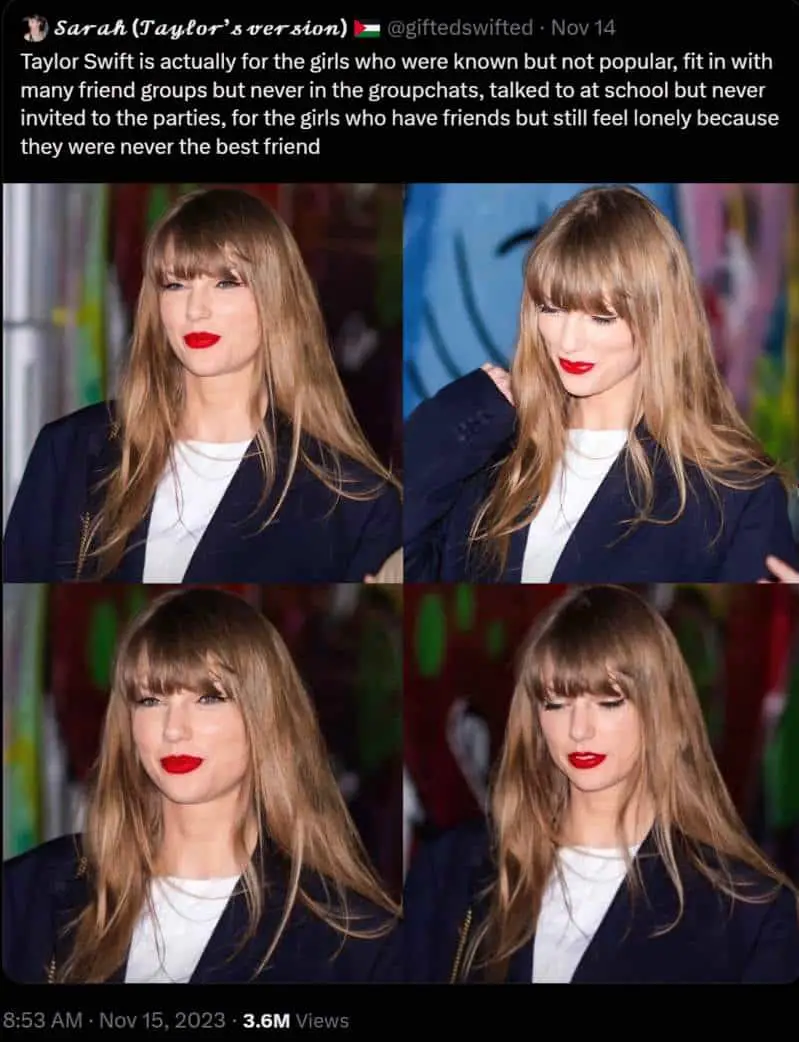

THE ICONIC BIG RABBIT

If you saw Donnie Darko a while ago and remember nothing else about it, I’m guessing you probably remember there’s a big creepy rabbit in it. The rabbit is an example of resonant imagery and is especially valuable in a visual medium such as film. (That said, I just checked. The resident teenager only remembered the jet engine scene and had completely forgotten about the creepy rabbit.)

Frank didn’t do much for the popular appeal of rabbits, but rabbits had already been on the downward slide, probably since their introduction into countries where they wreak havoc.

Their lessening popularity was probably also helped along in the public imagination by the publication of children’s books such as Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present, illustrated by Maurice Sendak of Wild Things fame. The year before Where The Wild Things Are, in 1962, Sendak scored the job of illustrating a bunny story by Charlotte Zolotow and he came up with this creepy ass thing:

Other big rabbits are familiar to children of the late 20th century, for instance this one by John Burningham.

And here’s a creepy big rabbit from a perfectly innocent picture book from 1963:

SETTING OF DONNIE DARKO

This film is Realism on the surface, but also makes heavy use of Surreal dream sequences. While watching, take note of which scenes are more purple and which are more brown.

PERIOD

Although this film was made in 2001, it is set in the 1980s. This means the director set the film in a time slightly before he himself would remember. The writers of Stranger Things did the same thing.

Why? Modern audiences think of the 1980s nostalgically, the way 1980s audiences regarded the 1950s and 60s. By taking audiences back to a nostalgic time of American economic security (at least for suburban white folks), Donnie Darko is an ironic take on 1980s nostalgia. “Were the 1980s really all that good?” we might wonder.

POLITICAL LANDSCAPE

We know (at least, American audiences know) immediately that Donnie Darko is set in the 1980s because Dukakis is running for president. Democrat Michael Dukakis ran against George Bush in the 1988 American Presidential election, and of course lost. (As a non-American, I had completely forgotten his name.)

In hindsight, Dukakis was running a doomed campaign. ‘Doomed’ is a theme of Donnie Darko in general.

DURATION

We are given an exact date, set in the past.

The exact date lends realism: October 2, 1988, or 28 days, 6 hours, 42 minutes, and 12 seconds before the end of the world. It also succinctly lets us know what might happen and functions throughout the story as a ticking clock, driving the narrative forward. (Coincidentally, the film was also shot in just 28 days — incredibly quickly.)

LOCATION

The location is an archetypal American suburb. In American stories, suburbs often equals death, if not literally then psychologically. Donnie Darko is a good example.

Richard Kelly grew up in Midlothian, Virginia, which was the town used in the original script. But the setting was later changed to Middlesex. The movie is intended to be set in Virginia, but was actually shot in Southern California. If you’ve ever been to Virginia, you can tell Donnie Darko isn’t really taking unfolding there (the suburban landscape is off) — but the backdrop is meant to be a stylized, satirical version of what Kelly remembers of Midlothian, Virginia.

i-d vice

Donnie Darko filming locations

ARENA

This suburb is near a mythical forest, replete with the witch (Roberta Sparrow, Grandma Death) who lives in the cottage near the edge of it. Donnie spends most of his time between home and school but also on the golf course, another ironic take on wilderness, since golf courses are the least natural ‘wilderness’ imaginable.

MANMADE SPACES

Like the suburb, Donnie’s school is as ‘Every School’ as possible. Some people see this film as a critique of the American educational system.

NATURAL SETTINGS

The story opens with Donnie waking up in a place removed from civilisation. The entire film maintains a stark division between the wilderness of this place (the symbolic forest) and the civilisation of the suburbs.

WEATHER

Though this does not come through in pathetic fallacy such as rain and thunder storms, Donnie Darko is dark in all respects: Dark subject matter, ‘dark’ in the title/symbolic character name, and dark in cinematography. Below is a poster generated from the dominant colours of the film. The cinematography was done by Steven Poster. Donnie Darko is a dark purple film, with plenty of brown.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

A plane

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

Donnie’s family is petty-bourgeois, and via Donnie’s cynical point of view, we join him in despising this milieu.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

There are signs of economic progress all around, but Americans of this era are in the pursuit of happiness. Why are they not happy with what they already have?

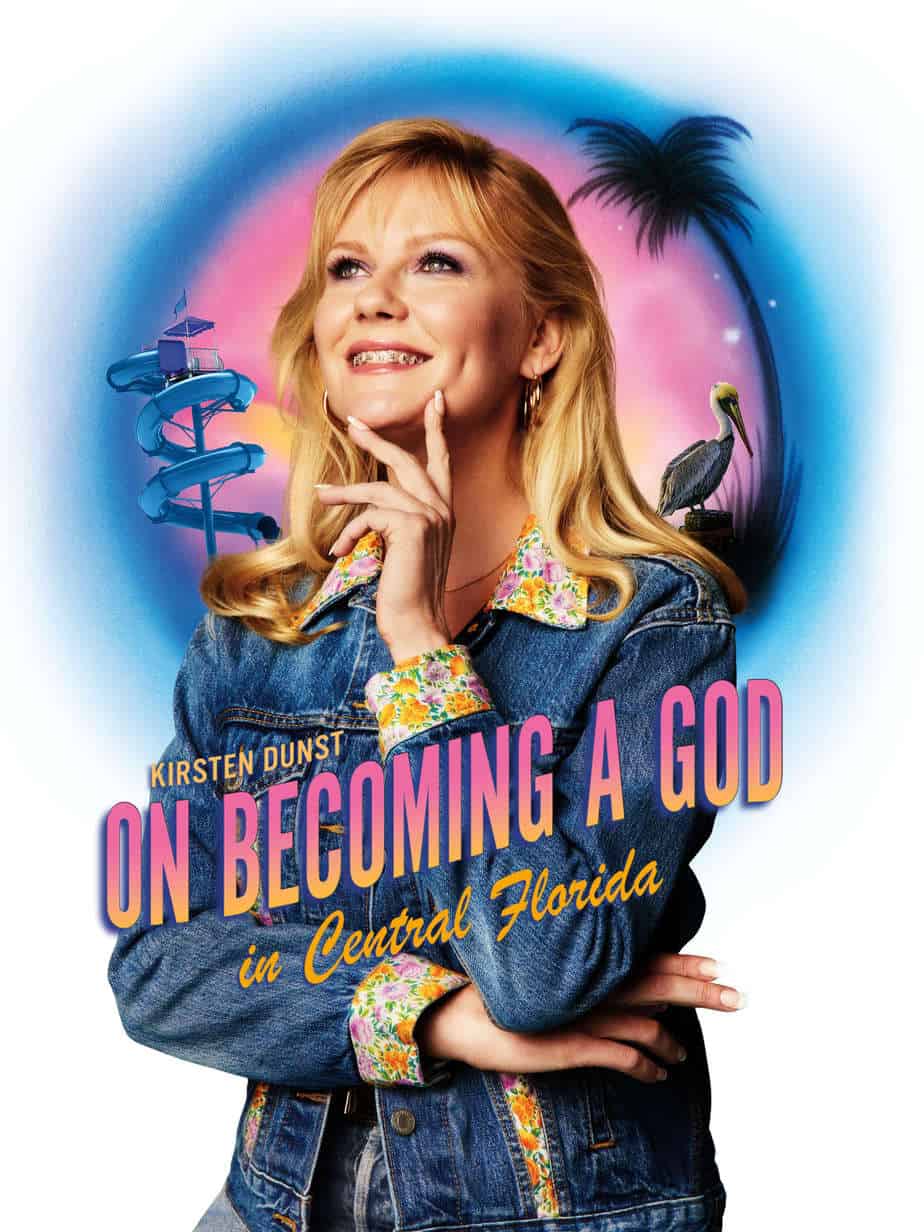

2019 TV series On Becoming A God In Central Florida is set in 1992 when the fruitless pursuit of happiness was at its American peak.

Donnie Darko, at its heart, is about authenticity. This is an especially resonant young adult concern, as young adults are at a developmental stage which questions what is true and what is false in the world, including what they’ve been told by authority figures.

STORY STRUCTURE OF DONNIE DARKO

PARATEXT

Tagline of Donnie Darko

A troubled teenager is plagued by visions of a man in a large rabbit suit who manipulates him to commit a series of crimes, after he narrowly escapes a bizarre accident.

It wasn’t a conventional adulthood [coming-of-age] film in the American Pie way. Donnie talks about jerking off, but that’s only a part of it. His psychological journey is what’s important. That’s why it’s had this lasting power. Anything psychological has a slower — but ultimately longer — burn.

Jake Gyllenhaal in The Guardian

Significantly, Richard Kelly was in his mid twenties when he wrote and directed this film. This is an #ownvoices film, if we consider ‘youth’ an identity. (Debatable.) Kelly wasn’t long out of high school himself. That said, he was thirteen years old in 1988 when the story is set. He is younger than his fictional main character.

Inspiration For The Film

Sometimes writers start with a theme, sometimes with an image. In this case, Richard Kelly read a news item:

I was 23, just graduating from film school, and in a panic trying to write a screenplay to get my career started. I remembered a news story I’d read as a kid: about a huge chunk of ice that fell from the wing of a jet and hit a boy’s bedroom, but he wasn’t there and escaped being killed. That gave me the seed of an idea.

The Guardian

Symbol Webs In Stories With Cult Followings

Cult audiences love to work before uncovering meaning from a work of art. Jokes work via a similar mechanism. An obscure joke divides an audience into ‘them’ who don’t get it to the ‘us’, who do. Donnie Darko is rich in symbolism.

Story Structure of Donnie Darko

For me, Donnie Darko is a Sliding Doors plot in which the audience is presented with two parallel realities, based on a moral decision made early in the story by the main character. In this case, Donnie must decide whether to listen to the bunny or not. In the first play-out, he listens to the bunny. The bunny saves his life.

But then, precisely because he listened, he does a great job of ruining his own life, as well as the lives of others. However, he lives a very full life in a very short time.

In the second play-out, Donnie has not listened to the bunny. He is killed. He dies without experiencing the love of a girlfriend, and various other coming-of-age things.

SHORTCOMING

Like many young adult characters in fiction, Donnie is a weirdo, an outsider.

Donnie is also a departure from the archetypal hero of early 2000s blockbusters. To use Northrop Frye’s categorisation of mimetic heroes, he appears to be low mimetic: an apathetic teenager, stuck in a family unit, stuck in school. He has little autonomy. But he is also an anarchist saviour type. This makes him more of an antihero. But the fact he is very much not a superhero is highlighted right on the page when Gretchen says, “”Donnie Darko? What The Hell Kind Of Name Is That? It’s Like Some Sort Of Superhero Or Something.” Also in common with superheroes such as Bruce Banner, Billy Batson, the Caped Crusader, Clark Kent, Lex Luthor and Peter Parker, Donnie Darko has an alliterative name.

Specifically, Donnie is a Postmodern Oedipus. Like Oedipus, Donnie knows what’s coming to him. (Melancholia is another film starring a Postmodern Oedipus, only this time she is female.) Here’s the thing about Oedipal (anti-)heroes: Even though they know what’s coming for them, they have no choice but to embark upon a mythical journey towards catharsis first.

We sympathise with Donnie because the story is told from his point of view. He also appeals because he’s smarter than people around him. Kitty Farmer is trying to persuade Donnie (and the rest of the young people under her care) to see the world in binaries.

DESIRE

At the beginning of the film Donnie wants to keep his mother happy, so he resumes the medication he has previously stopped.

OPPONENT/ALLY

Frank is a demonic bunny who whispers to Donnie that the universe will come to an end in less than a month.

The voice Donnie uses when he’s talking to Frank, the demonic bunny rabbit, was my choice. As well as being this trippy figure, Frank is Donnie’s only friend, almost like a comfort blanket. So the voice is how a child would talk to his blanket.

The Guardian

The bunny is basically an oracle. Is he an opponent or an ally? Both, perhaps. When characters in fiction know their own futures this is often a two-fold blessing and curse.

“You can do anything.”

Frank

GRETCHEN

Gretchen is the romantic opponent, a special category of opponent because romantic interests function as both opposition and ally. Donnie will later feel the need to avenge Gretchen’s death, probably mostly because of the romantic interest.

KIDS AT SCHOOL

Most of Donnie’s peers don’t accept him. He and his sister are both gifted intellectually, but Donnie has trouble figuring out socially acceptable responses within the highly proscribed context of school. That said, someone who stands up to farcical teachers garners a certain kind of social prestige, and Donnie has that.

KITTY FARMER

One of Donnie’s high school teachers is especially antagonistic. Alongside Donnie’s therapist, this gym teacher stands for authority. She commodifies happiness by teaching it in class, though this is far from the techniques taught by cognitive behavioural therapies. This is fast-food happiness in a can.

KAREN POMEROY

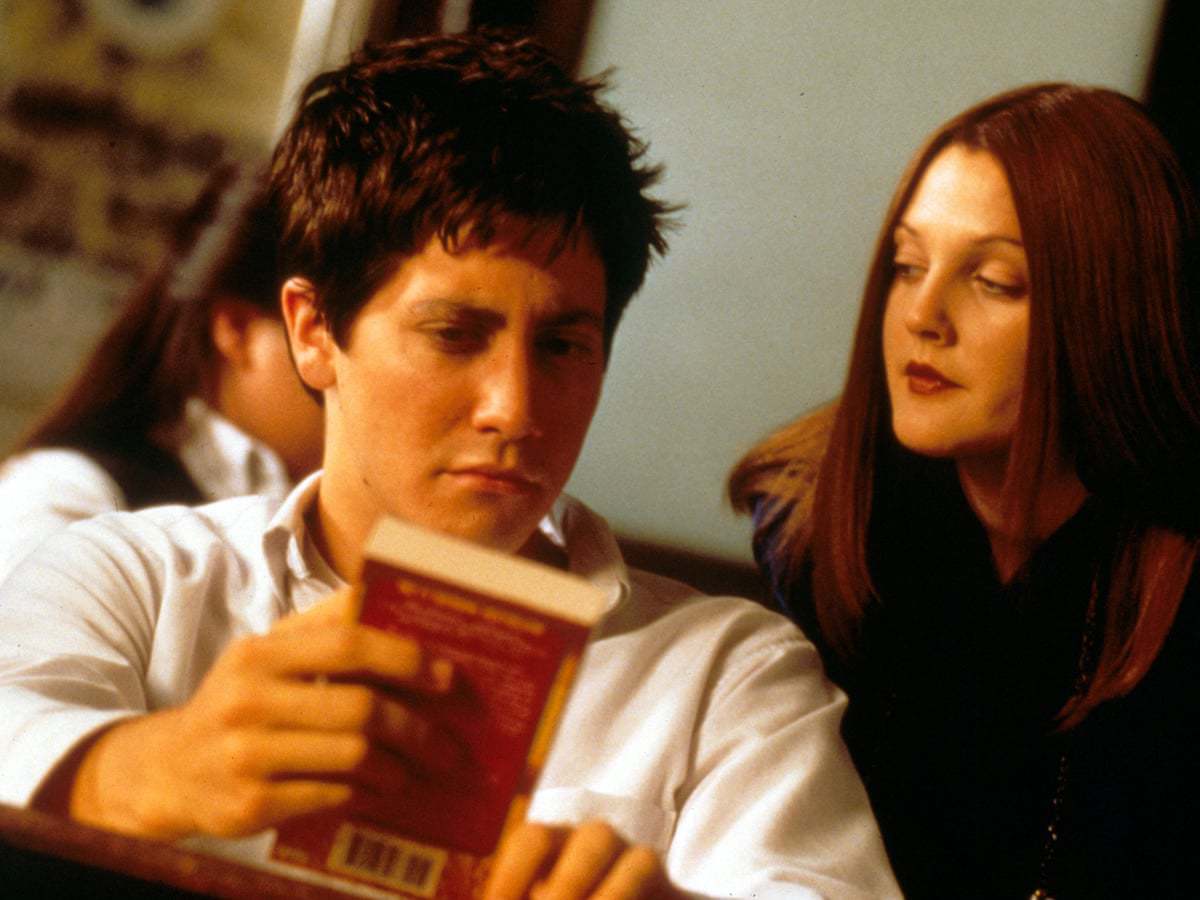

In contrast to the middle-aged gym teacher is the young, pretty English teacher Karen Pomeroy played by Drew Barrymore. (Middle aged woman teachers get a bad rap in fiction, despite forming the engine of the entire teaching profession.)

English teachers can be useful in stories because they have the vocabulary to teach the audience what to expect from a story. In this case, Miss Pomeroy talks about deus ex machina, which foreshadows the deus ex machina coming later in this particular story. Meta, huh?

When Karen Pomeroy is fired despite being way more level-headed than Kitty Farmer, this is a critique of the American education system.

DONNIE’S PARENTS

Oftentimes in stories about young adults the parents are the main figures of authority, but not in this case. Donnie Darko takes another common option: The parents are out of the way because they are hapless and largely ineffective due to their lack of understanding about their own son’s state of mind. Heroes can’t afford to spare much time thinking about the importance of their own families. They exist to serve the greater good.

Donnie’s father is similar to Mr Bennett of Pride and Prejudice. He finds his family farcical and laughs at their antics rather than stepping in to help. This is set up right at the beginning, during the dinner table scene.

CHERITA

Cherita exists as a contrast to Donnie. Like Donnie, but for different reasons, Cherita is also a high school outcast. Unlike Donnie, Cherita submits to Kitty Farmer’s binary view of the world because she is rewarded for it.

The bus-stop scene at the beginning of the film also serves as a Save the Cat moment, in which Donnie’s humanity is apparent when he tells the other guys to leave her alone.

PLAN

Donnie takes action in this film largely because he’s got a big rabbit called Frank whispering into his ear.

He seems to a have a little autonomy when it comes to Gretchen, and regarding the way he responds to the ridiculous teachers he’s forced to spend time with, but Donnie’s free will is up for debate at every level. This plays into a major theme: How much free will do we really have? Aren’t we all victims of our circumstance? Don’t we all have some kind of voice in our head, influencing how we behave?

There are a series of reveals over the course of this film, instigated by the voice in Donnie’s head, Frank.

Jim Cunningham, the motivational speaker, is revealed to be harbouring a dark secret. Like a fictional Bill Cosby, this guy cultivates a wholesome image of himself on a stage precisely so he can do dirty deeds in private. No one can possibly suspect a guy who espouses ideas about conquering fear through love, right? Because Donnie is privy to this information, he destroys his mansion.

Six hours before the time Frank said the world will end, Donnie realises he is supposed to save the world. This will change his plans. He goes with his new girlfriend Gretchen to see Roberta Sparrow. He wants to learn how to time travel.

BIG STRUGGLE

This story is a great example of a structure which features two juxtaposing ‘battles’. Storytellers frequently make use of some kind of stage performance (or competition, or both) to convey a sense of climax. See Little Miss Sunshine and About A Boy as just a few examples.

In Donnie Darko, the little sister’s dance competition runs in parallel to Donnie’s much darker battle. While the sister is on stage, participating in something comparatively frivolous (though taken uber-seriously by the annoying pop-psych enthusiast teacher), Donnie is involved in a literal life and death struggle.

Instead of seeing Roberta Sparrow, Donnie and Gretchen end up in an altercation with the two main neighbourhood bullies in the street. Frank ‘happens’ to be driving down the road. He swerves to avoid hitting Roberta Sparrow. Unfortunately he runs over Gretchen instead.

Donnie shoots Frank in the eye. Roberta Sparrow walks over to Donnie. She whispers, “A storm is coming. You must hurry.”

Donnie carries the dead Gretchen’s body to higher grounds so he can watch this storm.

ANAGNORISIS

This is a Postmodern Oedipal story, so Roberta Sparrow’s prophecy comes true. Except unlike the Oedipal mythology, the audience hasn’t been let in on what that prophecy is. Instead we must watch and wait.

Most of the discussion around Donnie Darko is about what happens in the end. This is one of those films which leaves the audience to figure out the ending, a bit like a jigsaw puzzle. Stories built this way tend to garner cult followings, though mainstream audiences can be left frustrated.

Basically, at the end of the film Donnie travels back in time to undo the horrible events which we’ve all just seen unfold. Unfortunately for him personally, once he travels back in time he must die. (This at least solves the grandfather paradox of time travel.)

After the show-down which kills Gretchen, Donnie makes his way to a higher altitude, which is a sure sign the big Anagnorisis is happening. (Characters in fiction regularly go to mountain-tops, roofs and so on to learn something big.)

From this elevated position, Donnie (and the audience) watches on as the storm rips an engine off an incoming plane. At this point, Donnie is sent back in time to 28 days earlier.

WHY DOES DONNIE LAUGH?

Donnie is now in bed, laughing hysterically. This feels like a mystery to viewers. Why is he laughing? Is it because he has just realised he will die, thus saving the world, and all of his worries about the future evaporate?

He has realised that death isn’t the worst thing that can happen to someone. Though he doesn’t dress in black, Donnie is your archetypal Goth.

Also he’s just time travelled. I’d have some kind of massive reaction if I’d just achieved that amazing feat, too.

NEW EQULIBRIUM

The montage of characters at the end is a roundup of all the characters in the story who have been saved by Donnie Darko the Redeemer. Note that this list includes opponents as well as allies. Each character is shown in their usual environment, and we understand something of their habitus; we understand that each of these characters is a ‘type’. (Which one are you?)

The final scene is a conversation between a boy and a girl. The audience learns that despite his sacrifice, Donnie has died without leaving his name and fame as legacy. In contrast, the audience has just spent one hour thirty seven minutes inside his head. We will remember this mythical figure as we remember mythical heroes and legends.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Three Stories About Delusion: Donnie Darko, Melancholia and Horse Girl

In understanding how stories about delusion work, I’ll compare two other similar films — Melancholia (2011) and Horse Girl (2020). Melancholia, as stated by its creator, is an allegory for depression, though could equally be understood by an audience as a story about one person’s apocalyptic delusion.

Tagline of Melancholia

Two sisters find their already strained relationship challenged as a mysterious new planet threatens to collide with Earth.

Tagline of Horse Girl

A socially awkward woman with a fondness for arts and crafts, horses, and supernatural crime shows finds her increasingly lucid dreams trickling into her waking life.

Whether we’re talking about Donnie Darko, Melancholia or Horse Girl, these stories draw the audience into a state of madness alongside the main character. Horse Girl is more on-the-page than Donnie Darko and Melancholia in its treatment of mental illness. Donnie Darko does see a psychiatrist, so mental illness is ‘on-the-page’, but in Melancholia there’s no acknowledgement of mental illness. So all these stories sit at a different part of a spectrum regarding the overtness of mental illness.

There’s a scene from Horse Girl in which Sarah (probably schizophrenic) tells her psychiatrist that she knows what she’s saying is crazy, but she is describing an experience which feels very real to her. The psychiatrist replies with an acknowledgement that what Sarah tells him is very much true for her. And ‘for the sake of our rapport’, goes on to explain that he personally does not believe in aliens.

This is a great scene, because it so adeptly describes many states of delusion: Commonly, a delusional person knows exactly how ‘crazy’ they sound. It’s common for a person experiencing hallucinations to tell you about their hallucinations prefaced with, “I know it sounds crazy, but…”

There’s an analogue here for the relationship between an audience and any work of fiction: The audience knows exactly how ‘fictional’ the work ‘sounds’. But we believe it anyway. However, audience ‘belief’ in story does not derive from delusion; rather it comes after mindful suspension of disbelief.

How does a storyteller successfully plunge an audience into a simulation of delusion? Across all three film examples I see commonalities:

- In each case, the main character feels isolated and lonely, somehow inherently different from those around them. In a film, camera angles and editing help greatly in achieving this effect. Loneliness is also emphasised when the main character is surrounded by ‘normal’ people — or, people the audience would code as ‘normal’. Although audiences tend to side with main characters (audiences are like ducklings), in a story about delusion, it’s important that audiences also learn to see the main character as removed from society. We see the main character through the lens of other, normal characters, but at the same time we must empathise with the delusional character. This is a careful balancing act. If the storyteller introduces ‘crazy’ too soon, before establishing empathy with the main character, audiences will only see their experiences from the outside.

- But once all this has been set up, the veridical world of the story gets weird, or weirder. There’s already a weird, ominous tone established from the opening scenes, and now the storyteller reveals oddities in more detail. Audiences will be working to decide which of these oddities is true within the veridical world of the story, and which derive from some kind of delusion. Whose version of reality do we trust? The storyteller will present odd things, then via reveals the audience is shown that weirdness is coming from the delusional person themselves, not from some veridical opposition. For delusional main characters, they really are ‘their own worst enemies’.

- But because complete narratives require flesh-and-blood opponents in order to satisfy an audience, the story must include flesh-and-blood opponents. In all three cases, interpersonal conflict features heavily. And all three films feature opponents which exist within the character’s delusion: The rabbit (Donnie Darko), the planet about to collide with Earth (Melancholia), the aliens (Horse Girl).

- Interestingly, in each of these stories, the delusional main character has a love-hate relationship with the opponents of their delusions. Donnie Darko believes the rabbit is helping him to survive, actually saving him from death by warning him of future disaster. Ditto for Sarah of Horse Girl, who sees aliens rather than a rabbit. In Melancholia, Justine lies naked beneath the sky, offering herself in surrender to her opponent. (Sarah of Horse Girl also appears naked at the depths of her delusion — a scene Jake Gyllenhaal was not required to perform in Donnie Darko. I suspect a more general gender imbalance here — woman actors are more frequently required to appear naked for audiences, no matter the ‘story’ reason.)

- Also interesting, in both Donnie Darko and Horse Girl, the audience is shown where, exactly, the delusions come from. For Donnie, the image of the rabbit comes from a classmate’s Halloween costume. For Horse Girl, the delusions come from a supernatural show she binge-watched while grieving the suicide of her mother. Melancholia is less clearly about delusion, and is presented to the audience as if Justine is correct about the apocalypse all along — an Oedipal figure — so the planet itself is real within the veridical world of that story. (Others can see the planet. Everyone knows about it.)

- As each story progresses, more and more time is spent looking at the world from the main character’s point of view. But at the same time, there is a certain amount of switching back to that outsider’s, ‘normal’ person’s point of view. Audiences are shown exactly how the delusional main character is sabotaging their own life. Donnie is up to all sorts of dark mischief, doing as the rabbit tells him. Justine is failing to enjoy her own wedding, behaving strangely. Horse Girl remains overly attached to a horse she has sold, and is breaking all sorts of social etiquette, wasting her money, sabotaging a budding relationship with a man presented as the perfect partner for her.

- This self-sabotage will culminate at the Battle scene, at which point the delusional character will come close to death, or come close to killing someone else, or in the case of Donnie Darko, actually kill someone else.

- Delusional main characters don’t necessarily achieve their own Anagnorisis. In the case of Horse Girl, the main character acknowledges that she sounds crazy. But her delusions continue. In the case of Donnie Darko, the time slip factor prevents any Anagnorisis because in the second, alternative universe, he dies. Any revelation is experienced by the audience, and that’s likely to be something like: “So this is how it feels to be delusional, in this particular character’s head.

- In all three examples of Donnie Darko, Melancholia and Horse Girl, the story ends firmly inside the main character’s head. Or does it? The audience is left to decide for ourselves, which version of reality is ‘real’. The New Situation is this: This is the main character’s reality now. It has no end. And if there’s no end to this feeling, then — for all intents and purposes — this world is the true world for this person. The message for audiences: Other people’s realities are as ‘real’ for them as your reality is ‘real’ for you.