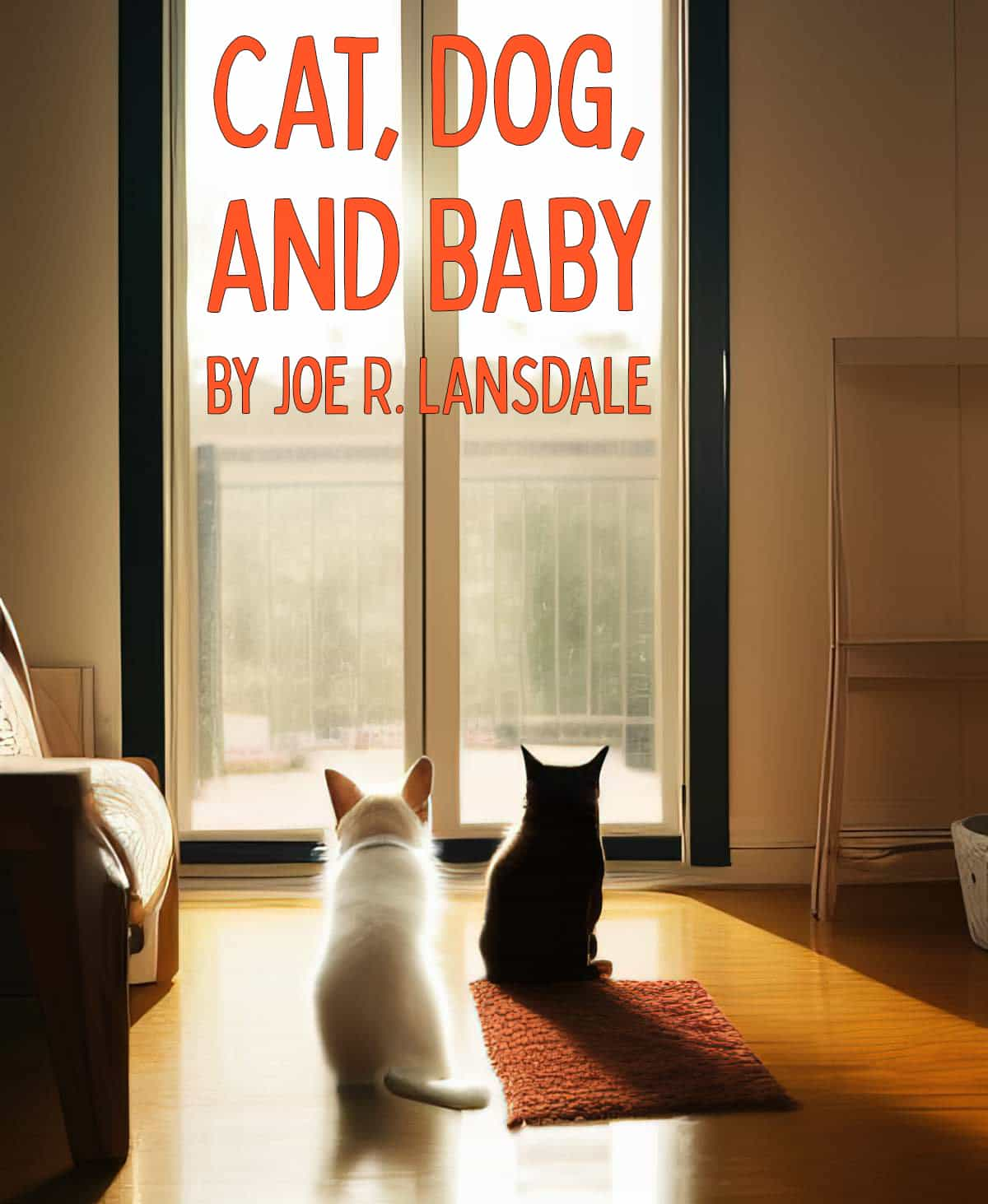

“Dog, Cat and Baby” is a very short story by Joe R. Lansdale, an American writer born 1951. This story is an excellent example of what I’ll call a double twist ending. (So if you haven’t read it, now’s your chance.)

First I’ll talk a little about how we anthropomorphise cats and dogs.

CATS AND DOGS IN FICTION AND CULTURE

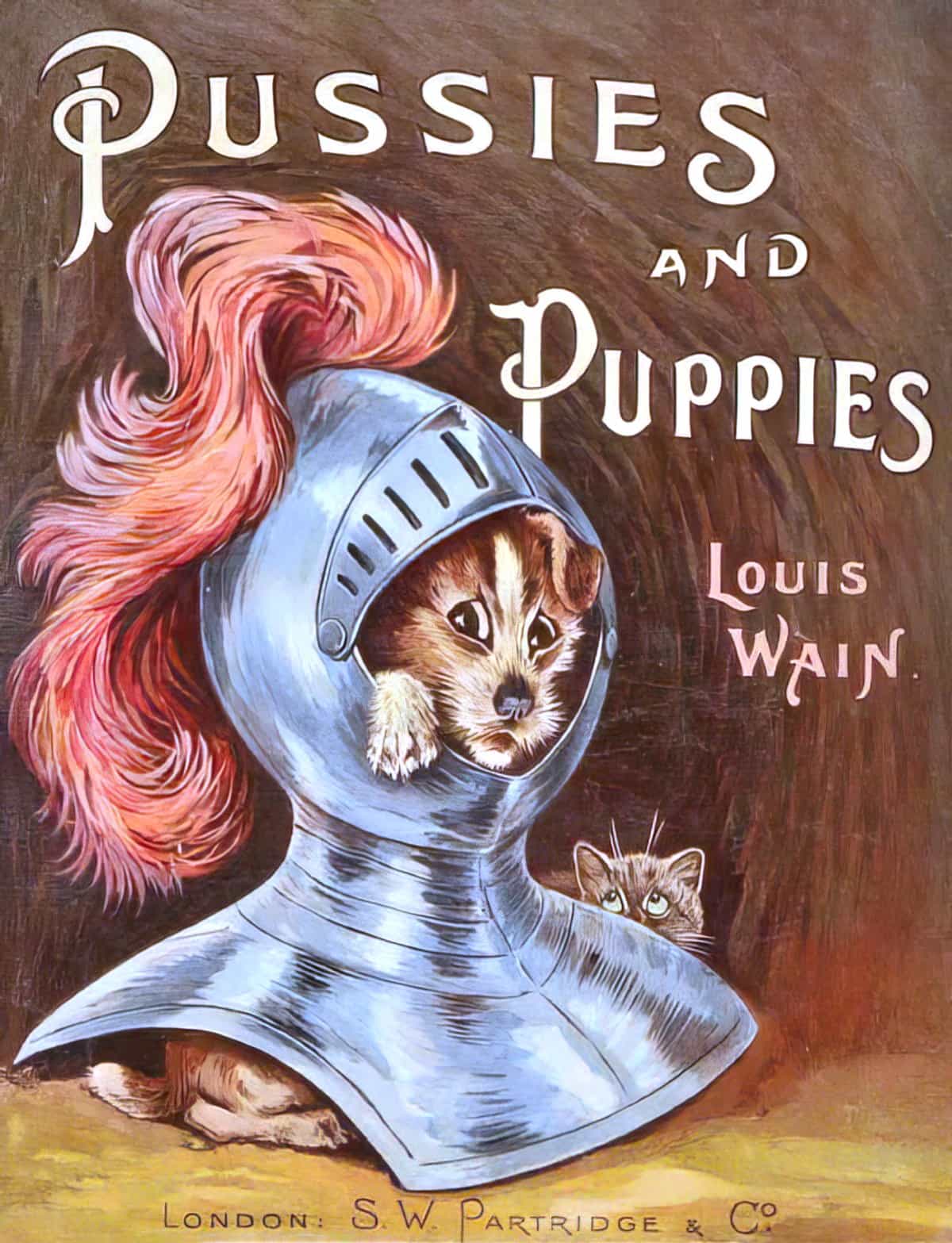

Cats are the female version of dogs, right? I’ve heard more than one person say that when they were little they used to think so. Of course, children’s literature and pop art leads kids directly to that conclusion. Take a look at these happy, heteronormative couples:

Anyone else see how cats as female, dogs as male is a reflection of human gender stereotypes? The rule doesn’t always hold, of course, and doesn’t hold in this story.

Garfield and Odie are both masculo-coded. The standout feature of Garfield is not his conniving slyness but his laziness. He’s basically a cat version of Homer Simpson.

Also, by keeping both Garfield and Odie male, this makes possible an entire subcategory of jokes about how Odie is physically affectionate and Garfield needs his own space. This joke wouldn’t work if one of them were female, partly because the joke requires a homophobic worldview before it’s funny. (Find the same variety of jokes in sit-com Friends, where it is far more obvious because the characters are not animals.)

As a compare and contrast to “Dog, Cat, and Baby”, we might take a Rudyard Kipling story, which Maria Nikolajeva offers as O.G. example of contemporary how the West anthropomorphises cats and dogs.

Dogs: stupid, loyal, friendly. Cats: evil, conniving, fastidious.

Rudyard Kipling’s etiologic story “The Cat who Walked by Himself” (from Just So Stories, 1902) depicts the nature of cats as unreliable and independent as opposed to dogs as man’s true friends. The cat is, in his own words, “…not a friend…not a servant,” he is “the Cat who walks by himself, and all places are alike to him.” The bargain between the cat and the humans, according to this story, includes the cats’ obligation to keep the house free from mice, to be nice to babies just as long as do not pull his tail too hard. For this, the Cat is allowed to be inside the house when he pleases, sit by the fire, and “drink the warm white milk three times a day for always and always and always.”

Maria Nikolajeva, Power, Voice and Subjectivity in Literature for Young Readers

(An etiologic or etiological story explains how things came about. We also call them porquoi stories, which means ‘Why’ in French.)

THE DOUBLE TWIST IN CAT, DOG AND BABY

- We expect the dog to murder the baby. Twist one: Actually, Cat saves the baby by killing the dog pre-emptively.

- We realise this may have been Cat talking all along. In this scenario, Dog is innocent. It was bad enough that Dog got the lion’s share of Cat’s attention, but now the baby is here, that’s a bridge too far. Cat gets no attention at all, so resolves the problem by murdering both of them at once. But before he does, he explains why he’s doing it, blaming it all on Dog, who cannot defend himself.

The reason this second twist works: Lansdale’s simplistic, baby-like sentence structure. Since we code dogs as toddler-like, naïve and stupid, this feels like a dog’s voice. Also, whichever pet is writing this story is referring to themselves in the third person, distancing themselves and their own culpability. Really, it could be anyone, including the Baby (who lived to tell the tale?)

When we read the story again, the dog as innocent reading seems more likely.

- ‘Cat had not been a problem, really.’ (Does this sound like something Dog would say?)

- ‘Wouldn’t take much to rip little Baby apart.’ The act of ‘ripping’ is more reminiscent of claws than jaws (though both cats and dogs use jaws as well).

- The narrative viewpoint sees Dog from an outside point of view. We are shown how he drools, how he creeps across a room towards Baby. These are medium angle shots, as if someone (Cat) is watching from a short distance away.

- The cat puts itself first in the title, as you’d expect of an egomaniac.

SIMPLE LANGUAGE IS SOMETIMES THE MOST HARROWING