“Doctor Jack-o’-Lantern” is a short story by Richard Yates, the first in his 1962 collection Eleven Kinds of Loneliness. The story of the new kid in school is very popular in children’s literature, which is of course written for children. But what might a New Kid In School story for adults look like? This is it.

Richard Yates himself was often the new kid in school. His parents divorced when he was three years old. Much of his childhood was spent in many different towns and residences.

I was also often the new kid in school, because my father worked for the New Zealand post office, and throughout the 1980s small toll exchanges kept being shut down and centralised. So our family had to move from smaller towns to increasingly bigger ones. I went to six primary schools in all. I identify with Vincent in this story because on my first day at the first of my new schools (I was almost six) I decided to put my hand up for news. I was of course selected, and I remember standing there in front of everyone and having no idea what to say. I didn’t even understand the concept of news, a new tradition for me at this new school.

So I made something up. None of the lies I told struck me as wrong, and I enjoyed it very much because the kids all laughed at my stories. Even the teacher laughed.

One day I reported that our neighbour’s chimney had caught fire. The firemen had come to put it out. This was all true, and my classmates listened in awe. But then I said the fireman’s hat fell down the chimney. I felt a little bad when my classmates all seemed to believe this too. Unlike Vincent, my teacher never told me to stop lying. He just laughed along, and I was often picked for news. Every single time, I had no idea what I was going to say until I got up there. Little of it was true. But the following year something must have happened to me developmentally because in my new classroom with a new teacher I would never volunteer for news. This new reticence continued until I was in senior high school when I again found my voice — this time, not lying.

A New Kid In School story written for adults can be more realistic than one written for a child audience. Everything about Richard Yates’ “Doctor Jack-o’-Lantern” rings emotionally true, including the climactic act, which would not pass the gatekeepers in a story written for kids, but which is exactly the kind of thing that happens in schools. We often say that the girl code is impossibly complex and full of pitfalls, but in this story Richard Yates shows us that the unspoken rules of boys are equally complex and exclusionary.

Another reason why this adult version rings true is because Yates’s omniscient, insightful narrator allows the reader understanding of the teacher’s actions. Miss Price is as rounded as the child main character, Vincent, nicknamed Dr. Jack-o’-Lantern. In contrast, most children’s stories make use of teacher archetypes, with rare examples in young adult literature bringing a teacher in as a rounded main character.

SETTING OF DOCTOR “JACK-O’-LANTERN”

I’m guessing this story is set in 1932, which is when the Dr Jekyll a Mr Hyde movie came out. In this adaptation more than in the 1941 release, the teeth as described by the children in this story are a prominent feature of the main character’s monstrous alter ego.

Richard Yates was born in 1926, which would make this a story set in the time of his own early school days. If Miss Price had been married, she may have been forced out of a teaching job, opening the way for someone ‘who needs it’ ie. a man. Miss Price is quite a forward-looking teacher for the era, probably because of her age. By inviting the students to the front of the class to share their own news she is engaging in what was then known as a Progressive education style, which is less chalk-and-talk teacher-centric. (Also for this reason, the story could be set later. But I don’t think it could be set any earlier.)

The school of “Doctor Jack-o’-Lantern” is somewhere in commuting distance of New York, in the outer boroughs.

If I’m right about the timing of this story, what else was going on in America in the early 1930s? These were the dark days of the Great Depression, which hit America badly. Fourteen million people were unemployed. The world was preparing for another world war, though the children are busy with their own small factions to understand any of what’s happening in the wider world. It is likely that a kid like Vincent has had to move because his adult caregivers have been forced out of work, and have possibly found new work (hence some of his clothing items are new, some are old).

absurdly new corduroys, absurdly old sneakers and a yellow sweatshirt, much too small, with the shredded remains of a Mickey Mouse design stamped on its chest

Vincent Sabella reminds me of Wanda Petronski of The Hundred Dresses by Eleanor Estes, illustrated by Louis Slobodkin. Sabella is a Sicilian last name, and the new kid is speaking in an accent unfamiliar to his classmates, perhaps because he is a recent immigrant, perhaps because he has grown up around recent immigrants, speaking English as a second language. Vincent’s new classmates probably don’t know the scary connection between Italians and the mafia, but they seem to have absorbed some of the xenophobia of their dominant culture.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “DOCTOR JACK-O’-LANTERN”

SHORTCOMING

Vincent Sabella’s strength is also his shortcoming, and this is partly what makes this short story masterful. He is desperately lonely. We know from the omniscient narration that he comes dangerously close to burying his head in his teacher’s lap. But this is not how the other boys see him at all. His isolation is what makes him a mysterious figure. Vincent will face a dilemma. We can’t call this a moral dilemma, because he is too young to really understand what he is doing and why he is doing it. But the adult reader can see that Vincent can either remain an outcast among his peers by following the code of conduct set down by their teacher, or he can have a shot at being included by his peers by following the code of the playground.

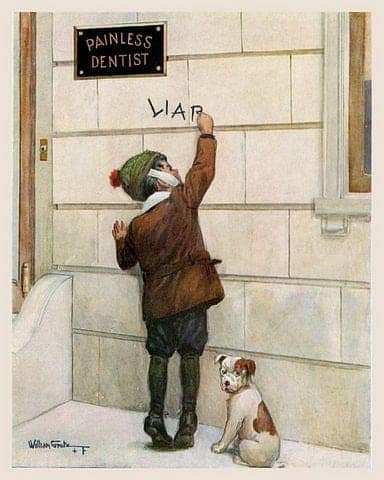

In both Eleanor Estes’s story for children and in Richard Yates’ story for adults, an immigrant child is ostracised by white, middle class children for being a liar (or perceived as one, in the case of Wanda Petrowski). Certain demographics are more likely to be seen as liars. The playground code in this white microcosm of society is complex for the uninitiated: Writing rude words on a wall in chalk: Admirable. Lying to peers: shun-worthy.

We can guess that the rules of Vincent’s New York world are quite different. There, bigging yourself up is probably an expected part of masculinity. It seems to me that Vincent is indulging in a particularly masculine form of storytelling — the tall story — when he tells his ‘lies’ to his peers. The tall story is more popular in some cultures than in others. Here in Australia it is an historically masculine tradition, told to mates in the bush, and the understood code around the tall story is that your narratees know you’re spinning a story. The rule is: believe nothing, lest you open yourself up as gullible. The more ridiculous the story, the more obvious the lie.

Vincent has told a ridiculously improbable story, but has made a huge social faux pas by assuming the kids in his new school would understand he is telling a tall story. He has already seen Nancy ‘lie’ by saying “Well” when she knows she’s not supposed to open that way. The minor untruth in that case is that Nancy never reveals to Miss Price that she knew all along not to say it. But Vincent will take that cue and run with it.

DESIRE

Vincent wants some friends. This connects to his underlying need: To avoid loneliness. Many stories have this exact desire — this part of a story doesn’t need to be sophisticated at all. All New Kid At School stories start from a place of loneliness.

OPPONENT

The children in the class are presented to us via the omniscient narrator as both highly recognisable and not especially empathetic.

The opponent of Miss Price is interesting because this story is an excellent example of a story in which the opponent genuinely wants the best for the main character. Again, the omniscient narration is an excellent choice for this particular story because the reader sees exactly why Miss Price behaves as she does. As adults, we probably put ourselves in her shoes. But because we’ve all been children, we can equally put ourselves in the shoes of the children.

PLAN

Importantly, Yates doesn’t let us inside Vincent’s head in the way we’re allowed inside Miss Price’s head. The story plays out before us, and we are as surprised as anyone else when Vincent’s plans take shape. ‘Plan’ is a loose term to use here because I imagine Vincent doesn’t ‘plan’ things out so much as follows his childlike, desperate instincts. Although we aren’t afforded a glimpse into Vincent’s motivations, Yates has given us enough to work with: We understand exactly why he does what he does.

BIG STRUGGLE

Vincent has two main opponents, the kids and the teacher, so we see two struggle scenes, the first with Miss Price, which is ironic because it’s the exact opposite of what Vincent wants. The second struggle takes place in the conversation with the other boys, in which Vincent lies he’s had the ruler on his knuckles. When Miss Price walks past and is very nice to Vincent, she unwittingly reveals him to be lying yet again. By being so nice, she has ruined Vincent’s shot at social capital.

ANAGNORISIS

Miss Price remains oblivious to what she has just done. We have earlier been told that children are a mystery to her, though I suspect boys are a mystery to her — she probably understands girl culture quite well. This is why Yates has chosen a young female teacher instead of an older, more experienced one. A male teacher may or may not have understood the rules of boyhood better and almost certainly would not have treated Vincent with so much motherly care. The complicated proto-sexual feelings these boys have for their pretty teacher is also important to the ending. Vincent epitomises the adolescent confusion of boys: Their teacher is both motherly and sexually appealing. These feelings together are supremely uncomfortable for them, and Yates shows this beautifully throughout the story by making use of juxtapositions. Finally we face the biggest juxtaposition of all: The loving care with which Vincent draws a lewd image of Miss Price.

NEW SITUATION

Yates can end his story as Vincent draws the image of Miss Price because he has given us enough information to extrapolate that Miss Price will be completely baffled by this act. She has already considered the fact that Vincent is a trouble child and she is out of her depth and will need to bring in outside help. That was for a lesser crime. So we extrapolate that this is now going to happen, and Vincent has unsuccessfully tried to fit in at his new school. The story probably won’t end well for Vincent.

This is where a similar story but written for children must end differently. Any child starting at a new school eventually finds friends and does reasonably well. At the very least, they find the inner strength to get through continuing tough times at school.

But Vincent Sabella has now branded himself as a sexual deviant, and in conservative 1950s America, he is doomed. This is a tragic story because as readers we’ve had our hands held by the narrator, and we know that Vincent does not deserve what’s coming to him.

This is especially true when we consider the longer historical view. Yates wrote this story decades after it is (probably) set, and the situation for Italian immigrants trying to settle in allied power countries was very grim throughout World War 2. After first being ostracised by his white classmates at school, Vincent may well have found himself ostracised later in life as an ‘enemy alien’. To avoid that, he may have gone to fight on behalf of America as a young man. Many Italian Americans fought on America’s behalf. This can’t have been easy, fighting for your country and also against your ancestral land. Vincent will have always felt like an outsider.

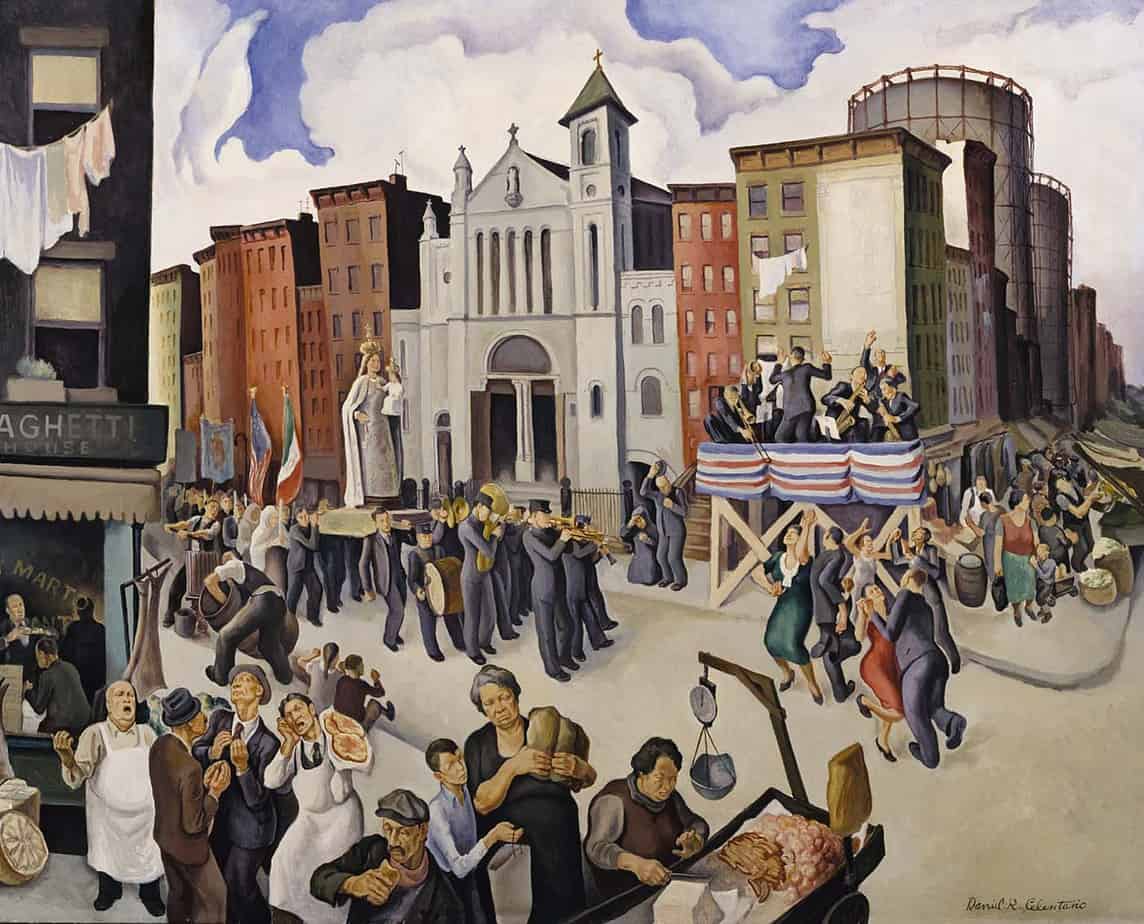

Header painting is “Festival” 1934 by Daniel R Celentano, set in East Harlem’s Little Italy, New York — “a lively scene, evoking the scents of tasty Italian food*, is overshadowed by the immense natural-gas tanks at the right that once blighted Manhattan’s immigrant slums,” according to the Smithsonian website.