Short answer: Main characters don’t have to be likeable. Nor do they have to be ‘relatable’. They only need be interesting.

Readers of fiction are unique in that they want to empathize with characters who are different from them, even if those characters make decisions that they may not personally want to make, or may not personally agree with.

Brit Bennett

I enjoy certain friends who aren’t necessarily “nice” people, because they’re like characters in a book who reliably make any scene they’re in more interesting.

Tim Kreider, Your Life Is Not A Story

First, some ideas from storytelling gurus who are not writing specifically about children’s stories but about stories in general. Lena Dunham has noted that female characters, like female people, are held to a higher standard when it comes to niceness:

“I sort of object to the notion that characters have to be likeable. I don’t like most of my friends, I love them. And that’s the same way I feel about most of the characters I write. So often, women are sort of relegated to sassy best friend or ingenue or evil job-stealing biatch, and it’s really nice to work somewhere in the middle.”

from Lena Dunham talking about Girls, quoted here.

People are used to seeing females portrayed as one of two mutually exclusive stereotypes. They want a sweet, down-to-earth protagonist pitted against a conveniently evil, bitchy foil. That way they know which one they’re supposed to “identify with.”

Suzanne Riveca at The Short Form

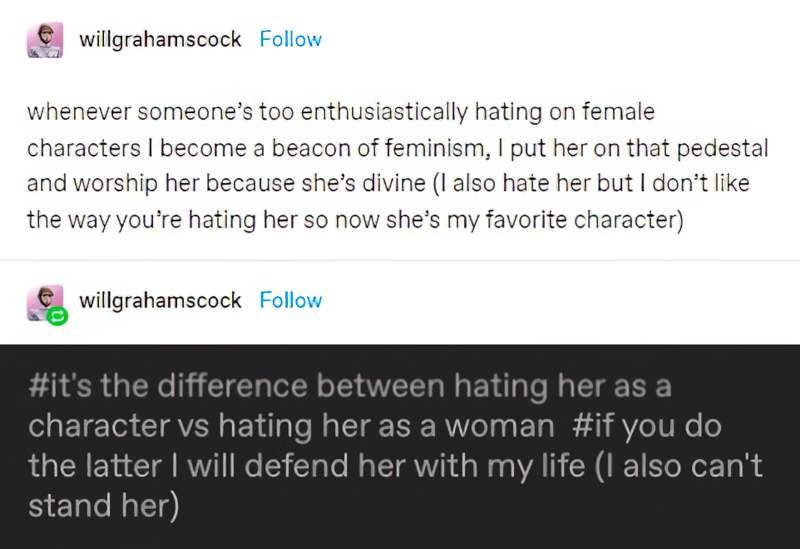

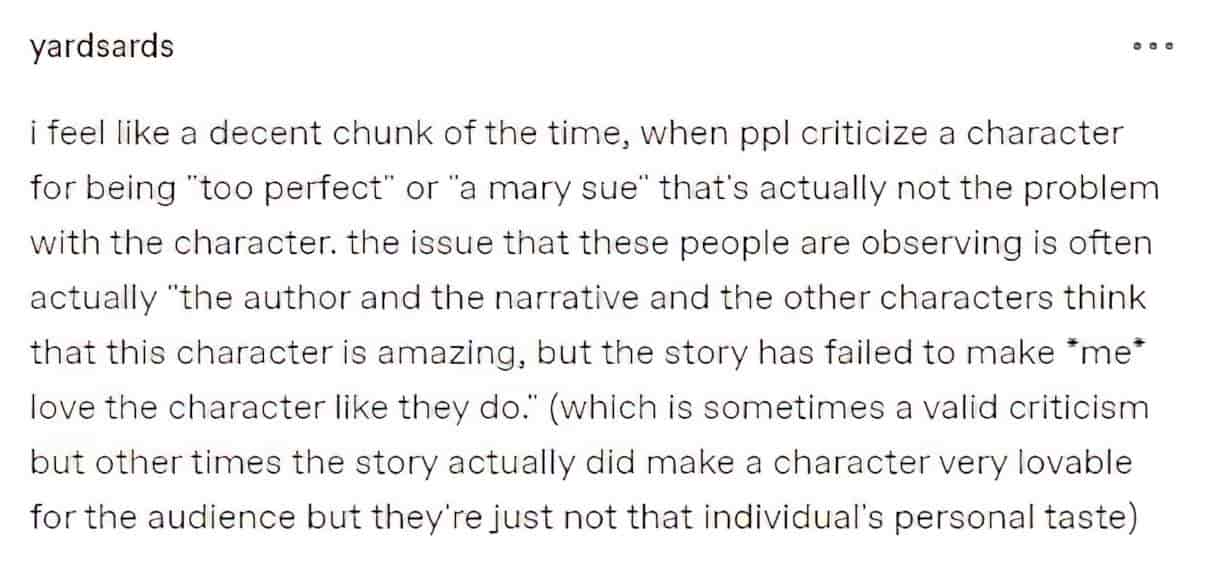

tumblr is always like, we need more morally grey female characters, and im like,,, okay but will you be able to recognize one when you finally get her? or will you hold everything that makes her morally grey against her like its a bug of her writing when its actually a feature???

rnorningstars

This is the age of the male antihero. It hasn’t always been this way, as described by Maria Nikolajeva in Children’s Literature Comes Of Age:

- The struggle between good and evil is the most common motif in fantasy.

- In early texts, often written by men, evil is depicted as a female figure.

- Female writers tended to write male monsters (e.g. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein)

- Male writers made much use of witches

- Examples of out-and-out evil witches in stories written by men: The Queen of Hearts in Alice In Wonderland; her twin in Through The Looking-Glass; the witch in The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald; the wicked witch in The Wizard of Oz; the witch in Narnia; The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen

- (I’m reminded of the old tradition of referring to boats: men called boats ‘she’ while women called boats ‘he’, but since men have had more to do with boats over the years, now everyone tends to call them ‘she’.) At the source of this literary gender switching with monsters was perhaps the fact that the opposite sex tended to be regarded as not fully understood and therefore not fully human. This is the theory put forward by Nancy Veglahn, at least.

- For example, Hans Christian Andersen’s problems with women are well-known (apparently): In Andersen’s early life, his private journal records his refusal to have sexual relations. (Wikipedia). C.S. Lewis can be subjected to similar psychoanalysis by critics.

- The opposite sex is not outright evil, but feelings are complicated by sexual attraction and love, which is expressed through the good female images: the reasonable Alice, MacDonald’s emancipated princesses, Dorothy who is both courageous and resolute despite feeling helpless, Lucy as the favourite in the Narnia stories.

- Veglahn also points out that female monsters were primarily sexual symbols.

- But females as evil characters goes all the way back to traditional witches in folktales, or to the ambivalent good/evil progenitor in myths, which may couter Veglahn’s theory.

- Modern female writers who have created evil baddies as male: Madeleine L’Engle, Ursula Le Guin, Susan Cooper, Natalie Babbiet, which also tend to feature male protagonists.

- Stories which do not fit this gender thing are Lord Of The Rings and The Hobbit, but there are hardly any female characters in those stories at all.

- Diana Wynne Jones’ Howl’s Moving Castle is another exception, with a female baddie by a female writer. Or characters in Darkangel by Meredith ann Pierce. In both cases, the authors write of the sexual attraction of the protagonist to the evil monster. Writers (mostly women writers) seem like they’re trying to free themselves from sex stereotyping, thereby creating new patterns.

- There are plenty of other exceptions, and more so since ‘good’ and ‘bad’ become more complicated, but there still seems to be a pattern.

RELATED

Writer’s Digest has a useful breakdown of villainous tropes and archetypes, and of course there is a different set of tropes for the stock characters.

ON XENA AND A LACK OF FEMALE VILLAINS from The Mary Sue

I hate Strong Female Characters from The New Statesman, because “Sherlock Holmes gets to be brilliant, solitary, abrasive, Bohemian, whimsical, brave, sad, manipulative, neurotic, vain, untidy, fastidious, artistic, courteous, rude, a polymath genius. Female characters get to be Strong.”

WRITING STRONG FEMALE CHARACTERS: DEFINING A BITCH from Writer’s Digest

25 MOVIES WITH BAD GIRLS AND BAD-ASS ROLES THAT KICKED DOWN THE DOOR AND TOOK NO PRISONERS from Cleveland. (These articles keep popping up in my feed. Is this saying something about what viewers want?)

The Villainess, a poem by Jeannine Hall Gailey from The Library And Step On It

I have nothing against lovable characters; there are a great many wonderful ones out there, and no one ought to go out of his or her way to deny a character’s best qualities for the sake of being called “uncompromising, hard-edged.” But our first obligation is to create interesting, suggestive, realistic, possibly even challenging situations, set our characters down in them and see where they go. Which may not be the way you wish they could; rather it is the way, given who they are, they must go.

Rosellen Brown

Here’s John Yorke, from his book Into The Woods:

If it’s difficult to identify a protagonist then maybe the story is about more than one person (say East Enders of Robert Altman’s Short Cuts) but it will always be (at least when it’s working) the person the audience care about most.

But already we encounter difficulties. ‘Care’ is often translated as ‘like’, which is why so many writers are given the note (often by non-writing executives) ‘Can you make them nice?’ Frank Cottrell Boyce, a graduate of Brookside and one of Britain’s most successful screenwriters, puts it more forcibly than most: ‘Sympathy is like crack cocaine to industry execs. I’ve had at least one wonderful screenplay of mine maimed by a sympathy-skank. Yes, of course the audience has to relate to your characters, but they don’t need to approve of them. If characters are going to do something bad, Hollywood wants you to build in an excuse note.’

Next, Yorke talks about what we might call the character’s shortcoming or moral flaw:

We don’t like Satan in Paradise Lost — we love him. And we love him because he’s the perfect gleeful embodiment of evil. Niceness tends to kill characters — if there is nothing wrong with them, nothing to offend us, then there’s almost certainly nothing to attract our attention either. Much more interesting are the rough edges, the darkness — and we love these things because though we may not consciously want to admit it, they touch something deep inside us. If you play video games like Grand Theft Auto or Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (and millions do), then you occupy literal avatars that do little but kill, maim, destroy, or sleep with the obstacles in your path. We are capable of entering any kind of head. David Edgar justified his play about the Nazi architect Albert Speer by saying: ‘The awful truth — and it is awful, in both senses of the word — is that the response most great drama asks of us is neither “yes please” nor “no thanks” but “you too”? Or, in the cold light of dawn, “there but for the grace of God go I”.

The key to empathy, then, does not lie in manners or good behaviour. Nor does it lie, as is often claimed, in the understanding of motive. It’s certainly true that if we know why characters do what they do, we will love them more. However, that’s a symptom of empathy, not its root cause. It lies in its ability to access and bond with our unconscious.

Robert McKee makes a distinction between empathy and sympathy, though I don’t personally find this distinction useful when it comes to creating a fictional character. However, he reassuringly agrees with John Yorke’s idea that the audience must bond with the audience on a deeper level:

The protagonist must be empathetic; he may or may not be sympathetic.

Sympathetic means likeable. … We’d want them as friends, family members, or lovers. They have an innate likeability and evoke sympathy. Empathy, however, is a more profound response.

Empathetic means “like me’. Deep within the protagonist the audience recognises a certain shared humanity. Character and audience are not alike in every fashion, of course; they may share only a single quality. But there’s something about the character that strikes a chord. In that moment of recognition, the audience suddenly and instinctively wants the protagonist to achieve whatever it is that he desires.

The unconscious logic of the audience runs like this: This character is like me. Therefore, I want him to have whatever it is he wants, because if I were he in those circumstances, I’d want the same thing for myself.” Hollywood has many synonymic expressions for this connection: “somebody to get behind,” “someone to root for,” All describe the empathetic connection that the audience strikes between itself and the protagonist. And audience may, if so moved, empathise with every character in your film, but it must empathise with your protagonist. If not, the audience/story bond is broken.

Story

The assumption that as readers we necessarily must identify with some character in the story we are reading has been seriously questioned by contemporary literary theory. Children’s writers have successfully subverted identification by creating a variety of repulsive, unpleasant characters with whom no normal human being would want to identify.

The Rhetoric Of Character In Children’s Literature

Nikolajeva also writes, “…children’s writers most often wish, probably for didactic purposes, to offer their readers a psychologically acceptable identification object.”

Children’s literature is different from adult literature in one main way: It has many gate keepers who are not the target audience. While publishers of children’s literature most often very open to characters with strong psychological flaws (understanding the way story works), books then have to make it past parents, librarians and teachers, who may hold the view that young readers blindly follow in the footsteps of naughty fictional children. Unfortunately, these (often conservative) gatekeepers have a very real effect on what actually sells, which no doubt influences what is published to some extent.

Another difference between stories for children and stories for adults: There are perhaps more Great Gatsby books in the children’s literature arena. By that I mean, they ‘star’ a main character who is actually the least interesting person in the story. They walk around as avatars for the reader, and because readers are all different, this avatar is as featureless as possible.

The brother and sister who star in A Series Of Unfortunate Events are almost completely featureless. Daniel Handler even avoided telling us anything much about how these children looked. They are instead surrounded by very quirky characters.

Bella Swan of Twilight is The Every Girl — white girl kind of pretty, who likes nothing out of the ordinary, and who mooches along causing no real trouble for anyone. Along with the Unfortunate Events children, Bella Swan is surrounded by a supernatural, unfamiliar world full of evil and suppressed desires.

Greg Heffley is arguably one of the least interesting characters in Diary of a Wimpy Kid. His diary is a commentary on what everyone else is like rather than a psychoanalysis of himself. Greg is The Every Child. (The every American mid-Western heterosexual able-bodied white boy.)

Anyone can see from reading reviews at Amazon and Goodreads that there is a swathe of the reading and book-buying public who do not like to read books with unlikeable characters. If they’re going to spend 300-600 pages with someone they want that someone to be the kind of character they’d happily invite over for a cup of tea. Their reasons for reading: To enjoy the experience. Unlikeable characters are more safely contained to shorter forms. We can better accept the company of a truly horrible character across 20 pages of short story. Would we stick with Mary Gaitskill’s “The Girl On The Plane” if it were a novel rather than a short story?

Another type of reader doesn’t have this requirement. This kind of reader can sound a bit more hi-falutin because, after all, you can’t read a lot of the classics if you start with the requirements that your characters have to be likeable.

James Wood makes clear his own position, criticising the type of reviewer who seems to think that:

Artists should not ask us to try to understand characters we cannot approve of — or not until after they have firmly and unequivocally condemned them.

How Fiction Works

This definitely has me thinking about picture books, and how certain readers require that any wrongdoing in a picture book must be punished, lest children think that it’s okay to steal hats, or whatever.

DOES IT MATTER?

Paradox Of Fiction: In the movie Vertigo, a former cop becomes infatuated with a persona invented to trick him. Like him, we form emotional attachments to fictional characters, which shows that our feelings can easily be evoked by illusions, and are thus not always valid.

Paradox Of Fiction

A MASSIVE PROBLEM WITH ACTIVELY WRITING LIKEABLE CHARACTERS

I believe one of the keys to writing fully realised characters is to refrain from judging them as an author. I don’t want the reader to feel as if I’m telling them which characters are good or evil, which ones they should like or hate. I want to get out of the way. I think my job is to tell the story almost like a good documentary filmmaker—with structure and style and good editing—but to let the characters and their actions speak for themselves. Every one of them has reasons for who they are and what they do.

Sometimes when a writer sets up big flashing arrows that say THIS IS THE BAD GUY or THIS IS THE HERO, I can sense that the author is trying really hard to make the reader like or dislike a character because of how THEY feel about that character. A character can be a coward, a killer, a tyrant, or have any number of unsavoury characteristics, but it’s not your job as the author to judge them. It’s only your job to tell the story. Are you using words like “evil smile” or “brave composure” that show your author’s hand?

This is why I disagree with the idea of characters having to be “likeable” because “likeable” is judgmental on the author’s part. A character is inherently more interesting and relatable to readers if they are not easily so pinned down and judged.

I consider it a big success when readers argue about my characters. When a character I’ve created has both fierce admirers and fierce detractors, it means they’re a lot more like real people. Try to write real people and not judge them. That’s all you need to do.

@FondaJLee

That said, if you’re writing a truly despicable character, or a character who does despicable things occasionally, you will need to go out of your way to use likeability tricks.

If people can slowly learn that characters from marginalized backgrounds don’t actually have to be “relatable” to be masterfully crafted, when will they learn that craft elements that don’t follow the western standards/defaults/context aren’t automatically “badly written”

It’s possible to not like a thing and say so, but to cast a craft judgment on it without even learning about, say, the specific context in which it crafted, reveals a bit too much about which school of lit one considers the default

@joanhewrites

IN WHICH LIKEABILITY ABUTS FEMINISM

Romance sits at the heart of your stories. What do you think makes a character a compelling love interest and a partnership that readers will root for?

It’s all about characterisation. The two people have to be created in great detail and have some degree of likeability before readers can be convinced to care, I think. (I feel tragically old-school insisting that fictional characters, especially women, have to be likeable. Even though the gender-political implications are obvious to me, I find it impossible to make a person I don’t like my main character. I have such admiration for writers such as Louise O’Neill who have no fear of writing not-likeable heroines.)

Marian Keyes: ‘Weaving comedy into a darker story is something that needs a lot of care’

A few years after James Wood published How Fiction Works, novelist Claire Messud was asked by a journalist to comment on why the main (female) character in her novel The Woman Upstairs isn’t very likeable. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that her response to Publishers Weekly sounded so well-thought through it was almost prepared; after all, James Wood and Claire Messud are married. I think they may have discussed this issue together, with Messud adding to the conversation that female characters are judged more harshly for being unlikeable, as are women in real life.

Lena Dunham spoke on the issue of likeability after criticisms that her characters in Girls are unlikeable:

I sort of object to the notion that characters have to be likeable. I don’t like most of my friends, I love them. And that’s the same way I feel about most of the characters I write. So often, women are sort of relegated to sassy best friend or ingenue or evil job-stealing biatch, and it’s really nice to work somewhere in the middle.

from Lena Dunham, quoted here.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has since shown her in-depth understanding (garnered from her own real life, I bet) of how tropes work in tandem, and against women. In reference to a misogynistic article from the NY Post, Ocasio-Cortez tweeted:

This reinforces lazy tropes about women leaders in media:

– Older + seasoned, but unlikeable

– Passionate, but angry

– Smart, but crazy

– Well-intentioned, but naive

– Attractive, but uninformed or gaffe-proneIt’s unoriginal, lazy, and men don’t get the same either/or coverage.

These same paradoxes exist when crafting female characters for fiction.

If we take the enduring success of books such as Lolita, it’s clear that in literary works — the kind that take years or decades to write — the kind that will get reviewed in major publications, writers don’t need to create likeable main characters in order to make a mark.

If you are a self-published author on Amazon, however, the nature of user reviews suggest that likeable main characters sell more copies.

And if you aspire to be a popular author for children, that likeable hero rule is even tighter… for better or for worse. In fact, even in popular Hollywood films heroes have to have a ‘moral shortcoming’. In other words, they have to be treating other people badly in some way (too tied to their job to spend time with family etc). But this does not seem to be a rule in children’s books, especially in stories for very young readers. Heroes for children only need a ‘psychological shortcoming’ (shyness, anxiety, hyperactivity, a tendency to blurt out uncomfortable truths, trouble handing in homework, etc.)

I think it’s important to tell your story truthfully. And I think that’s a difficult thing to do, to be truly truthful, because it’s only natural to be concerned about offending people, or possible consequences. . . . Forget about likeability. I think that what our society teaches young girls, and I think it’s also something that’s quite difficult for even older women, self-confessed feminists, to shrug off, is this idea that likability is an essential part of the space you occupy in the world. That you’re supposed to twist yourself into shapes to make yourself likeable, that you’re supposed to kind of hold back sometimes, pull back, don’t quite say, don’t be too pushy because you have to be likeable. And I say that is bullshit. . . . If you start off thinking about being likeable you’re not going to tell your story honestly. Because you’re going to be so concerned with not offending. And that’s going to ruin your story.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie from a speech at a Girls Write Now banquet

Rashida Jones was fired from the Toy Story 4 development team. She had this to say:

Women are taught to be nice. Men are taught to be powerful.

“When I was writing ten years ago, I took what is typically considered a male character and would give it to the woman,” Jones said. “I’d get feedback saying, ‘She’s not likeable.’ I would think, ‘So fucking what. Every guy isn’t likeable, until he is.’ Women are taught to be nice. Men are taught to be powerful. I want to find a way to tell stories from a woman’s perspective that doesn’t feel like it’s been put in the mouth of a woman by a guy.”

Indiewire

The story becomes even worse for female characters (and actual women) whose femaleness intersects with other things:

“i’m just so tired of watching how people talk about morally gray boy characters vs morally gray girl characters.

the boys get praised & coddled. the girls get torn down & judged. if your dark prince can be a secret cinnamon roll, why not the bloody princess?

i could write an entire academic paper, by the way, on how this is just symptomatic of how men—especially allocishet white men—are coddled/forgiven in real life, and women are punished.

i will not tone myself or my female characters down to fit some arbitrary, impossible “likeability” mould.

also, everything that diverts a female character from the white, skinny, traditionally attractive, abled, allocishet mould just makes them even MORE harshly evaluated. stacks the stakes even higher against them.

and hey, hmm, while you’re here, maybe think about how you’re judging the in real life women in your communities based on these standards. who do we come down hardest on? who do we watch most, waiting for a “mistake”?

Christine Lynn Herman on Twitter

The sit-com Fleabag is a concerning window into how likeable female characters need to be self-hating before we like them:

The Young Millennial Woman – pretty, white, cisgender, and tortured enough to be interesting but not enough to be repulsive.

One of the few things associated with millennials to have received a positive public reception is a particular form of millennial art. This art revolves around an archetypical Young Millennial Woman – pretty, white, cisgender, and tortured enough to be interesting but not enough to be repulsive. Often described as ‘relatable,’ she is, in actuality, not. The term masks the uncomfortable truth that she is more beautiful, more intelligent, and more infuriatingly precocious than we are in real life. But her charm lies in how she is still self-hating enough to be attainable: she’s an aspirational identifier. She’s often wealthy, but doesn’t think too much about it. Her life is fraught with so much drama, self-loathing and downwardly mobile financial precarity that she forgets about it, just as we are meant to. Her friends, if she has any, are incorrigible narcissists, and the men in her life are disappointing and terrible. Try as she might, her protest against the world always re-routes into a melancholic self-destruction.

Another Gaze

A Brief History Of Likeability

Likeable vs unlikeable characters are subject to fashion. In the 1990s there were a lot more unlikeable main characters, particularly in comedy.

An audience’s perceived wish to be around a likeable main character also varies according to region. It’s pretty clear that a British audience has a higher tolerance for unlikeable characters than an American audience. An interesting case study there is the character of David Brent, who is a thorough turd in the British version of The Office, but played in a more doofus, loveable fashion by Steve Carrell in the American series. The unlikeable British comedic character goes back further than Ricky Gervais’ creation — take Basil Fawlty in Fawlty Towers, or Penelope Keith’s character in To The Manor Born, who treats everyone around her with disdain and was even quite pleased when her first husband died.

Morally corrupt is on an entirely different spectrum from ‘likeable’

In the 2000s, Tony Soprano is the archetypal antihero, neither likeable nor unlikeable in my view but interesting nonetheless — and definitely morally corrupt. Morally corrupt is on an entirely different spectrum from ‘likeable’.

Don Draper is not a guy I’d like to know, and I believe he was written to be unlikeable, but on the screen handsomeness counts for a lot and I got the impression many heterosexual female fans of Mad Men didn’t mind Don Draper as much as they were perhaps meant to.

Breaking Bad ushered in a new wave of stories about ordinary, decent men who get sick of the system and decide to go full crim. More recently we’ve had Ozark, which is similar to Breaking Bad in many ways.

Bad Santa is an example of an unlikeable, disgusting person, but even he has his posse — people who will follow him around. This makes him a little more likeable.

Will Ferrell in Anchorman, and quite a few Will Ferrell characters are also unlikeable.

AS FOR CHILDREN’S LITERATURE SPECIFICALLY

There are few genuine distinctions between what sells in children’s literature and what sells to adults, not least because adults buy all the children’s books.

Children’s literature expert Maria Nikolajeva writes:

Some contemporary characters in children’s fiction efficiently alienate the reader by being unpleasant and thus offering no clear-cut subject position. While Mary Lennox in The Secret Garden, repeatedly described by the author as “disagreeable” in the beginning, quickly gains the reader’s sympathy, being an orphan and exposed to the adults’ indifference; a character staying unpleasant throughout the story may leave the reader concerned and even frustrated.

Nikolajeva is perhaps offering a rather cynical view when she also says, “…children’s writers most often wish, probably for didactic purposes, to offer their readers a psychologically acceptable identification object.”

THE REQUIREMENTS OF SHITTY TV SHOWS

This is where there’s a place for unlikeable characters.

- Mindless

- Irredeemable, flawed characters

- You feel like you’re in a position to judge the people you’re watching. “Whatever I’ve got going on, it’s not that.”

- Soapiness, melodrama

- If they’re better than you, the characters have to be better in really sexy ways

- Ridiculous salaciousness

as explained by Roxane Gay in a Nerdette podcast.

FURTHER READING

- 12 Great Movie Characters We Hate By The End Of The Movie from Film School Rejects

- WOULD YOU WANT TO BE FRIENDS WITH HUMBERT HUMBERT?: A FORUM ON “LIKEABILITY” from The New Yorker AND Claire Messud to Publishers Weekly: “What kind of question is that?” Do you like Jonathan Franzen’s characters? David Foster Wallace’s? Roth? Then stop asking Claire Messud about hers, from Salon

- I Like Likable Characters And I don’t like female novelists’ new method of dismissing other female writers, Slate

- Female Protagonists: Do They Need to be Friend Material? from Writer Unboxed

- Forcing Readers To Like Characters from Moody Writing

Cinema’s First Nasty Women

What makes a nasty woman? Is it her unwillingness to break to the stringent standards of patriarchy, her gameness to get rough, even abject? Or is it the way she reminds polite society that the sweet, gentle screen martyr (the nasty woman’s counterpart) is a fiction too, as much a trick and a dupe as an exploding housemaid on celluloid?

And what a surprise—and what a treat—to discover cinema’s earliest days are among their nastiest. Coming from Kino Lorber this December, “this four-disc set showcase more than fourteen hours of rarely seen silent films about feminist protest, slapstick rebellion, and suggestive gender play. These women organize labor strikes, bake (and weaponize) inedible desserts, explode out of chimneys, electrocute the police force, and assume a range of identities that gleefully dismantle traditional gender norms and sexual constraints. The films span a variety of genres including slapstick comedy, genteel farce, the trick film, cowboy melodrama, and adventure thriller. Cinema’s First Nasty Women includes 99 European and American silent films, produced from 1898 to 1926, sourced from thirteen international film archives and libraries, with all-new musical scores, video introductions, commentary tracks, and a lavishly illustrated booklet.”

interview at New Books Network