“A Dill Pickle” is a 1917 short story by Katherine Mansfield. Over the course of a single café scene, a woman meets up with a former beau. This is a feminist story about how men and women tend to communicate, and illuminates Mansfield’s deep interest in psychology.

I’m in a restaurant in Cambridge and this woman just yelled at a man “economics is part of culture” and he shouted back “that’s YOUR notion” and five minutes later she said, “do you want this” and he said “what is it” and she said “a pickle”

@sarahlovescali 9:41 am – 11 Aug 2019

Here’s your soundtrack: horribly anachronistic but about a dill pickle. (There are no words so we must use our imagination.)

WHAT HAPPENS IN “A DILL PICKLE”

A man and woman meet after six years apart. It is revealed that they used to be prospective lovers/beaus. The entire story is a conversation between them, and the reader sees (hopefully) that this partnership is doomed. A modern reader can probably put names to some of the psychological tricks going down.

SETTING OF “A DILL PICKLE”

“A Dill Pickle” was published in October 1917. Also in October 1917: a Revolution happened in Russia when Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace. Tsar Nicholas II was executed along with his family the following year. 74 years of communism followed civil war.

The world was watching Russia. Vera’s beau keeps mentioning Russia, eventually mentioning a ‘Mind System’, but nothing about any actual political upheaval. He even insists that Russia is free from class distinctions. Ha! This is a man who focuses on small things, unable to see a bigger picture. His fastidious nature is magnified as a result. If he really understood — or even felt — the social upheaval going on in the world of 1917, he wouldn’t mind paying for cream. He is petty and, despite his privilege, dangerously apolitical.

We don’t know where the story is set, though the characters speak English and I imagine them in a London coffee house. Mention of ‘St James’s Street’ could refer to this street in London. Put yourself in street view and you’ll see there’s still a cigar shop there today! (I was surprised to see that.)

Although the coffee house where they meet in “A Dill Pickle” is decorated in faux-Japanese style, an authentically Japanese coffee house would unlikely offer a jug of cream, let alone a tall plate of fruit. All of these details feel like an ‘everywhere/nowhere’ sort of setting, which adequately reflects Vera’s romantic limbo.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “A DILL PICKLE”

SHORTCOMING

Vera is named — the man is not. The man is presented as a type — an archetype. He is an upperclass white man (we can easily deduce this) with serious social shortcomings, but whose privilege has meant that over the past six years he has ‘done well for himself’. This man is exactly the sort of man Vera feels she should be marrying. She’s of the same social class, or was. When Vera mentions she had to sell her piano, we see she’s living in genteel poverty. She has less money than is required to live comfortably in her natal class. She is also desperately lonely.

If only he weren’t such a dill.

DESIRE

Vera wants a male partner, presumably a husband. This was expected in 1917. If she doesn’t want this deep down, it is still expected, and there will be heavy social and economic penalties for remaining single. We don’t know how old Vera is, but six years have elapsed since she last saw this man, which indicates she’s probably in her mid twenties, at least, and it’s high time she was married. “The older one grows…” (I can’t imagine a 25 year old would be complaining of cold with regards to age, unless she doesn’t have enough to eat, which is possible. Perhaps she’s more like 45.)

OPPONENT

The man is her romantic opponent.

PLAN

Vera’s plan has taken place prior to the opening of the story: Due to social pressure and loneliness she has decided to give an old beau another chance, to see if he’s changed to the point where she can seriously consider dating him now. She’ll make it as informal as possible — they’re meeting for coffee and fruit, not for dinner. That way she can make a quick getaway if everything turns to crap.

(“A Dill Pickle” feels a bit like an older, literary example of that TV reality series Back With The Ex, in which no one actually ends up back with the ex, not that I’ve watched the entire thing, or anything.)

BIG STRUGGLE

As he spoke, so lightly, tapping the end of his cigarette against the ash-tray, she felt the strange beast that had slumbered so long within her bosom stir, stretch itself, yawn, prick up its ears, and suddenly bound to its feet, and fix its longing, hungry stare upon those far away places. But all she said was, smiling gently: “How I envy you.”

The conversation starts badly and gets worse. (I go into that below.) The final straw is when he launches into a lecture on a ‘Mind System’ he’s apparently learnt in Russia. (Men who go abroad, return home and talk incessantly about What They Have Learned must have been dime a dozen back then — humorous short story writer Saki also took the mick, for instance in “The She-Wolf“.)

ANAGNORISIS

In the past when they had looked at each other like that they had felt such a boundless understanding between them that their souls had, as it were, put their arms round each other and dropped into the same sea, content to be drowned, like mournful lovers. But now, the surprising thing was that it was he who held back.

Vera has learned that this guy’s gotten even more like his terrible former self. He’s no good for her, despite looking pretty good on paper. (He’s well-travelled, can afford caviar — though he complains of the cost — and he speaks in the same upper class dialect as she does.)

The reader is behind Vera, probably. We have only just met him.

So after Vera leaves we are helped along with our own revelation about the character of this man. Astounded as he is, he asks the waitress for the bill right away. He’s not going to dwell on this woman. We extrapolate he’ll get over her quickly. Then he asks that he’s not charged for the cream, which points to an unattractive degree of stinginess in someone from his class. Money matters to him more than human relationships.

She had buttoned her collar again and drawn down her veil.

NEW SITUATION

Vera remains alone.

Given the era, Vera may have remained alone forever. An entire cohort of men her age were killed during the wars, skewing the gender balance. When she draws down her symbolic veil, what does that mean? Mansfield might be referring to the bridal veil. Another short story of hers is called “Taking The Veil“, about a young woman about to become a Bride, fantasising about becoming a Bride of Christ. This tells us that Mansfield definitely considered the symbolism of the veil, as a two-way shield. Vera has clearly closed herself off, at least for the time being.

ANALYSING THE CONVERSATION

I can’t tell you how many first dates I overhear where the man never asks the woman a single question about herself but discusses his life endlessly. It’s depressing.

@rgay (Roxane Gay) 10:31 AM – 2 Nov 2019

KNOWING SOMEONE, REALLY KNOWING THEM

The man doesn’t recognise Vera at first, though she recognises him immediately. This suggests he never really knew her. Or, it could be that Vera is wearing a later fashion. Women’s fashions change more obviously than men’s. But when the man exclaims “I didn’t know you”, we will learn, like Vera, that he never knew her in the first place, and is unlikely to ever know anyone. He’s too fixated on petty issues.

Despite six years elapsing, and despite him failing to recognise Vera by appearance, the man is, later in the conversation, very keen to crack on how very well he knows her. For example, he ‘knows’ how much she smokes, and though they both sit at this very table smoking the very same tobacco, his smoking is a luxury whereas hers is a ‘habit’. That puts her below him, in his eyes.

When we are in the limerence phase of love, we have a strong tendency to see only the similarities between ourselves and the object of our affection, and to ignore all the ways in which we are different. “Oh, you like Coldplay? I also like Coldplay! We must be soul mates!!”

“And then the fact that you had no friends and never had made friends with people. How I understood that, for neither had I. Is it just the same now?”

He is the one with the ego problem, but in desperation he ascribes that problem to both of them, as if they’re both equally narcissistic:

we were such egoists, so self-engrossed, so wrapped up in ourselves that we hadn’t a corner in our hearts for anybody else.

Nope, that’s all him.

When a romantic possibility keeps telling you how very similar you are to them, they may be trying to manipulate the rate at which attraction more naturally grows. This is a man who would like to be regarded as a ‘limerant object’, to use the terminology of Dorothy Tennov. He longs to be adored in a romantic way, without offering the same in return. He may be on the narcissistic spectrum (a Mansfield speciality).

“What a marvellous listener you are. When you look at me with those wild eyes I feel that I could tell you things that I would never breathe to another human being.”

(Note the use of ‘wild’ eyes. He gleans a hint of the beast within her.)

The ‘you’re not like other girls’ speech:

“Before I met you,” he said, “I had never spoken of myself to anybody. How well I remember one night, the night that I brought you the little Christmas tree, telling you all about my childhood.

Recently I came across the term ‘depressive demon nightmare boy’ to describe the trope of the strangely attractive man with major psychological issues. This guy’s MO is miserableness. He is brooding, petulant, damaged and damaging. Though he is not supernatural, the man in “The Dill Pickle” fits this trope:

And of how I was so miserable that I ran away and lived under a cart in our yard for two days without being discovered. And you listened, and your eyes shone, and I felt that you had even made the little Christmas tree listen too, as in a fairy story.”

Hamlet is the standout O.G. of the depressive demon nightmare boy trope.

Here’s another warning sign:

“I felt that you were more lonely than anybody else in the world,” he went on, “and yet, perhaps, that you were the only person in the world who was really, truly alive. Born out of your time,” he murmured, stroking the glove, “fated.”

The man ascribes to the myth of the ‘one true love’. Or at least, pretends to, invoking ‘fate’, along with many, many stalkers and manipulators across history I’m sure.

FEMALE ACCULTURATION AND REPRESSION OF PHYSICAL SELF

For her part, Vera is playing typically feminine games. According to ‘civilised society’, real ladies are not permitted to have bodily functions. Toileting, sweating and even eating are considered unladylike. So when the man asks what she’d like, she is well-practised in not seeming eager, as if she really needs sustenance. Ladies are never greedy. ‘She hesitated, but of course she meant to’. Later, Vera feels a ‘hungry beast’ stir inside her. Contemporary television is full of characters with a ‘beast’ inside them. Nick Lowe’s The Beast In Me could have been used for any number of theme tunes apart from Tony Soprano’s: Don Draper’s, Walter White’s, the list does go on but they’re mainly men.

Occasionally though, you get a female described as ‘hairy on the inside’, as Angela Carter put it. Mostly, female characters described in this way are written by female authors, who fully understand the thin veneer of feminine civility (hence the closing veil reference!) concealing pent up rage. Unlike men, however, woman-beasts only need to walk out of a café to really buck the system. (Meanwhile, Tony Soprano goes on a killing spree…)

INTERRUPTION

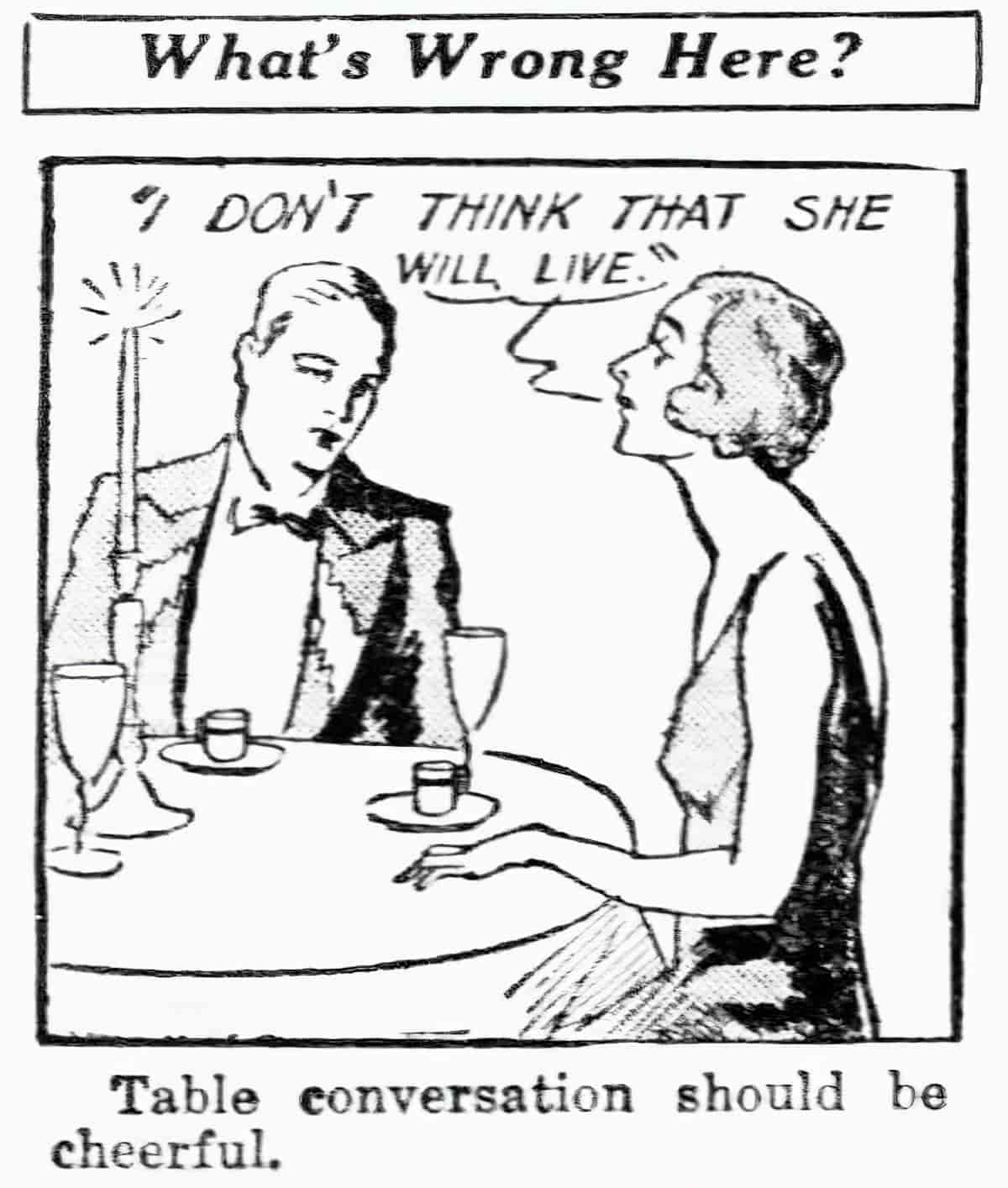

It’s well-documented that men interrupt women more than they interrupt other men.

Early studies on interruptions and related phenomena seem to indicate a larger tendency on the part of men to interrupt in cross-sex conversations while in same-sex conversations no significant differences were found.

Gender, Status and Power in Discourse Behavior of Men and Women

More broadly, people who consider themselves higher in the social hierarchy interrupt more often.

The participants in a conversation use a number of strategies to achieve their conversational goals. One of these goals may be to dominate other participants of the speech situation. The question whether gender or status and power is the motivating force for conversational behaviour has been resolved in favour of status and power in the literature. Most studies find that in mixed talks men tend to be more dominating than women.

One of the obvious strategies for achieving this goal, as we have seen, is the use of interruptions. Their use is generally explained by the relative power of the participants which derives from their social status. The higher incidence of interruptions, thus, is seen in the relatively high social and economic status of men.

Gender, Status and Power in Discourse Behavior of Men and Women

The man interrupts Vera regularly, but because his manners dictate he offer the opportunity for her to finish whatever she started, he doesn’t see this as a problem. Manners aside, he doesn’t listen to her. Vera is old enough to know exactly when it’s happening. We don’t necessarily notice ‘normal’ patterns of speech when we are younger, because gender asymmetry is the water we’re swimming in.

Despite constantly interrupting Vera, the man comments on how beautiful her voice is. This feels icky, aside from the false compliment. For him, women function as ornaments — the beauty of voice stands in for physical beauty, reminiscent of “The Little Mermaid“. He is not interested in the content of Vera’s words; he chooses only to listen to their melody. Speaking-as-background-noise, in other words. Even in a courting situation, when stakes are high, he’s not listening to his date. This does not bode well for a future partnership of equals. He’s even happy to admit he doesn’t listen to anything she says. She taught him the names of the flowers at Kew Gardens, which he has triumphantly discarded as irrelevant information rather than as a shortcoming on his part.

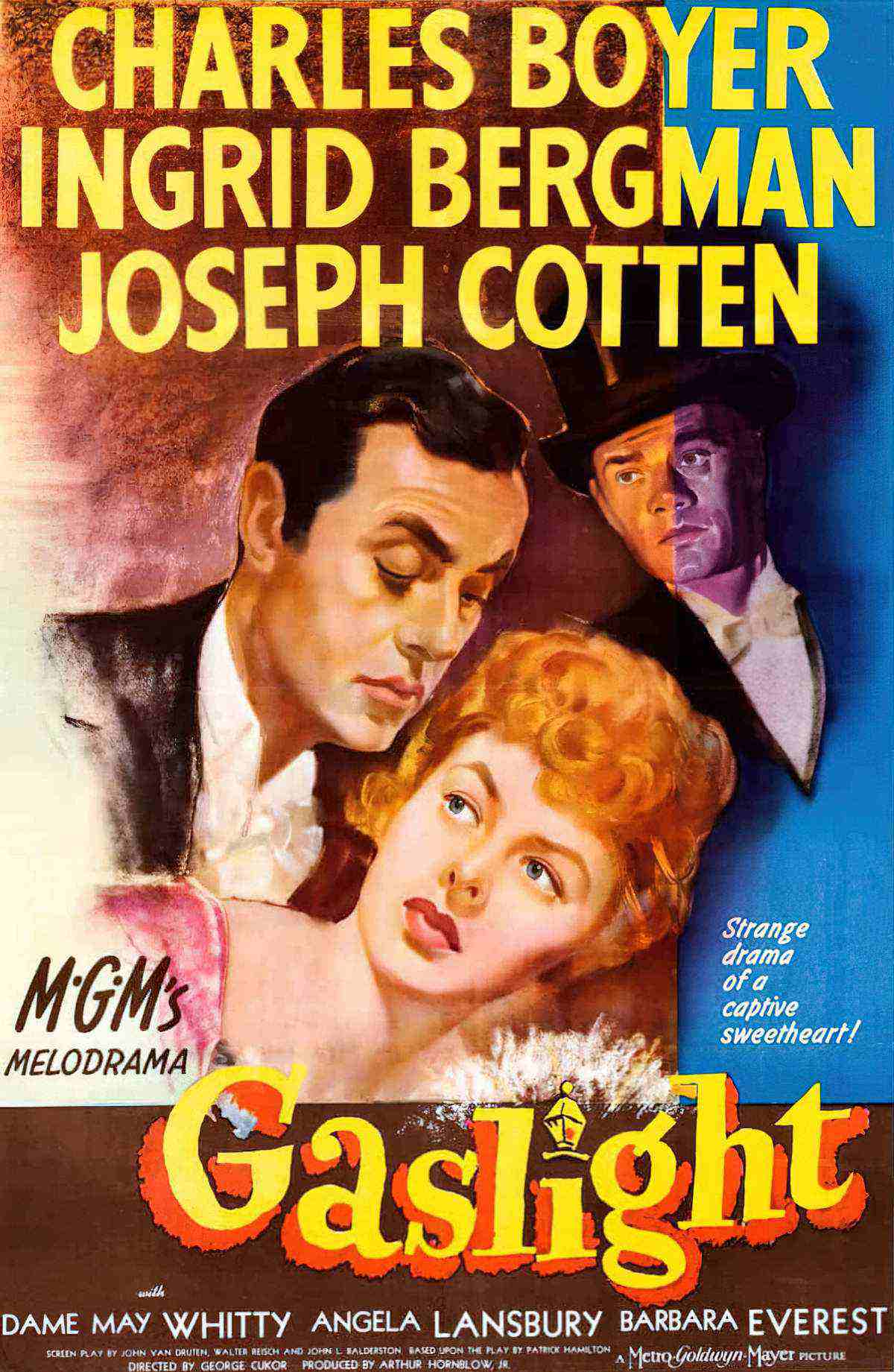

SORT OF LIKE GASLIGHTING BUT NOT QUITE

Initially, Vera recalls that afternoon at Kew with an overriding negative memory. The man descended into absurdity that day, waving wasps away at the tea table. But when he recalls how wonderful the day was, she decides to go along with his better memories rather than stick with the one incident which has tainted hers.

This isn’t gaslighting per se, but this is a relationship in which one partner is inclined to submit to the other’s ‘correct’ take on events. We witness Vera trying her darnedest to see the good in him — his optimistic view of the afternoon is far more pleasant than hers, after all. In some ways she might be better to learn from his half-glass-full outlook on life…

But then she recalls a similar memory in which he says, “I wish I had taken poison and were about to die — here now!” He says this in a moment of happiness, and Vera reminds herself that he’s not such an optimistic type after all, that she can’t necessarily take anything away from his ‘rosier’ outlook on life. A partner who speaks of death and killing themselves at the possibility of a romantic relationship coming to an end is engaging in manipulation and coercive control.

ATTRACTION TO… PRIVILEGE (NOT TO THE MAN)

Vera acknowledges that ‘he was certainly far better looking now than he had been then….Now he had the air of a man who has found his place in life, and fills it with a confidence and an assurance which was, to say the least, impressive. He must have made money, too.’ My interpretation: He’s a white man of privilege, and despite him doing nothing outstanding to earn any of these riches, he’s been swept along in that particular tide. His upper class attitude is underscored by his use of ‘little man’ in reference to the tobacco merchant. Mansfield regularly used ‘little man’ in her stories to indicate a superior, classist attitude.

He ‘casually’ mentions ‘When I was in Russia’. Travel in those days was not as it is today. In 1917, war travel aside, visiting Russia really was exotic. Such adventures would put the man at an elevated level of worldliness, at least in his own mind. (Travelling to far-flung places doesn’t make you worldly. Developing yourself as a person and cultivating a wide variety of relationships makes you worldly.) He lists all the countries he has visited, thinking of travel as an achievement rather than as a privilege, then announces his plans to travel to China ‘when the war is over’. This is a man who is not part of the war. He is waiting around for it to be over. He is a privileged draft dodger, probably. This is certainly the reading a 1917 audience would have ascribed.

The man is wholly unaware of the concept of privilege. When Vera reveals that she had to sell her piano, he simply cannot understand why. “But you were so fond of music,” he wonders.

He cannot imagine poverty. He has never experienced it.

RIVER SYMBOLISM

The man’s bullshit parsing of the river as metaphor is comical:

“That river life […] is something quite special. After a day or two you cannot realize that you have ever known another. And it is not necessary to know the language—the life of the boat creates a bond between you and the people that’s more than sufficient. You eat with them, pass the day with them, and in the evening there is that endless singing.”

He thinks that by surrounding himself on a luxury cruise, away from the war, with other members of his class, that it is the seclusion itself which creates the bond. It’s the privilege, dude. It’s the very privilege which banded you all together on that refuge riverboat cruise in the first place. He’s got cause and effect ass-about.

Vera understands this perfectly and ‘she shivered, hearing the boatman’s song break out again loud and tragic, and seeing the boat floating on the darkening river with melancholy trees on either side’.

THE DILL PICKLE

To the man, the offer of a dill pickle from a servant to his masters symbolises equality. In reality, this offer represents false equality, another kind of veneer. A dill pickle cannot possibly bridge the socio-economic gap, not least in Russia of 1917, ffs, when an actual revolution was going down.

Vera thinks she doesn’t know what a dill pickle is, but her description of the red chilli in the jar suggests she knows exactly what they are. She is still doubting her own take on things:

although she was not certain what a dill pickle was, she saw the greenish glass jar with a red chili like a parrot’s beak glimmering through. She sucked in her cheeks; the dill pickle was terribly sour. . . .

As reader, I’m waiting, waiting, for her to realise what a turd this man is.

As title of the work, “The Dill Pickle” may have other meanings attached.

I’ve heard ‘dill’ used as a mild insult, in reference to general stupidity.

Then there’s the ubiquity of dill used to flavour food throughout Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia and Ukraine. The man is a self-described expert on Russia, but his expertise as confined to his own little boat, as a pickle is confined to its jar. People who come home from abroad newly cultured frequently learned nothing new of a culture aside from the food dished up in the restaurants where they ate.

Speaking of small things inside containers, Katherine Mansfield used that motif a lot. It’s especially well done in “At The Bay“.

There’s also the phallic symbolism of a dill pickle, but it’s easy to see phallic symbolism in everything vaguely penis shaped, so I’m not sure how far to go with that. This man has the appearance of manliness — symbolised by the phallus — but so does the dill pickle. The dill pickle is also vaguely comical, in the same way bananas are. This guy would be funny if his kind didn’t run the actual world.

ASYMMETRY IN A RELATIONSHIP

Vera remembers the man’s childhood dog whereas the man had forgotten Bosun entirely. This snippet of conversation demonstrates the extent of asymmetry in their relationship. She knows things about him; he blunders on, knowing nothing and no one, not even himself. Vera has basically been fire doored.

Failing to understand his own self, let alone his former girlfriend, the man tries to win Vera back by launching into a lecture about a Mind System he studied in Russia. Goodness knows what that refers to. I imagine there was a popular psychological theory doing the rounds at the time.

A HISTORY OF FEMININE LYING

There’s a long, long history of women as liars in the stories we tell about human beings. Duplicitousness is thought to be an inherent aspect of a woman’s nature.

Sure enough, Vera is not disclosing her true feelings to the man. She smiles when she doesn’t mean it. “Not a bit,” she lies, denying he said something to hurt her. Is this a type of lying, or is it prudent?

The man feels like the 1917 version of a fedora wearing MRA, who wonders why women don’t like him.

He sat there, thunder-struck, astounded beyond words. . . .

Such men fail to understand their own part in a relationship and that bro-culture casts women as liars. The theory is, that if women were straight-up about their interest or lack of interest in a man, men would know where they stand and do a much better job of being a true partner.

But women have their own personal safety — both physical and emotional — to take care of. He has a history of making scenes in tea houses.

What, exactly, is one’s obligation when leaving a date? My answer: No one owes anyone anything. Katherine Mansfield has provided a valuable script which applies equally to modern dating. Use your intuition. If your date is truly terrible, extend basic civility, although it may mask your fear.

Then get the hell out, pull down your metaphorical veil and Don’t. Look. Back.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Mansfield was interested in probing the kinds of uncertainty that undermine (and overturn) some men’s and women’s claims to equal power. She does it here in “A Dill Pickle” and she also does it in “Something Childish But Very Natural” and in “The Stranger“.

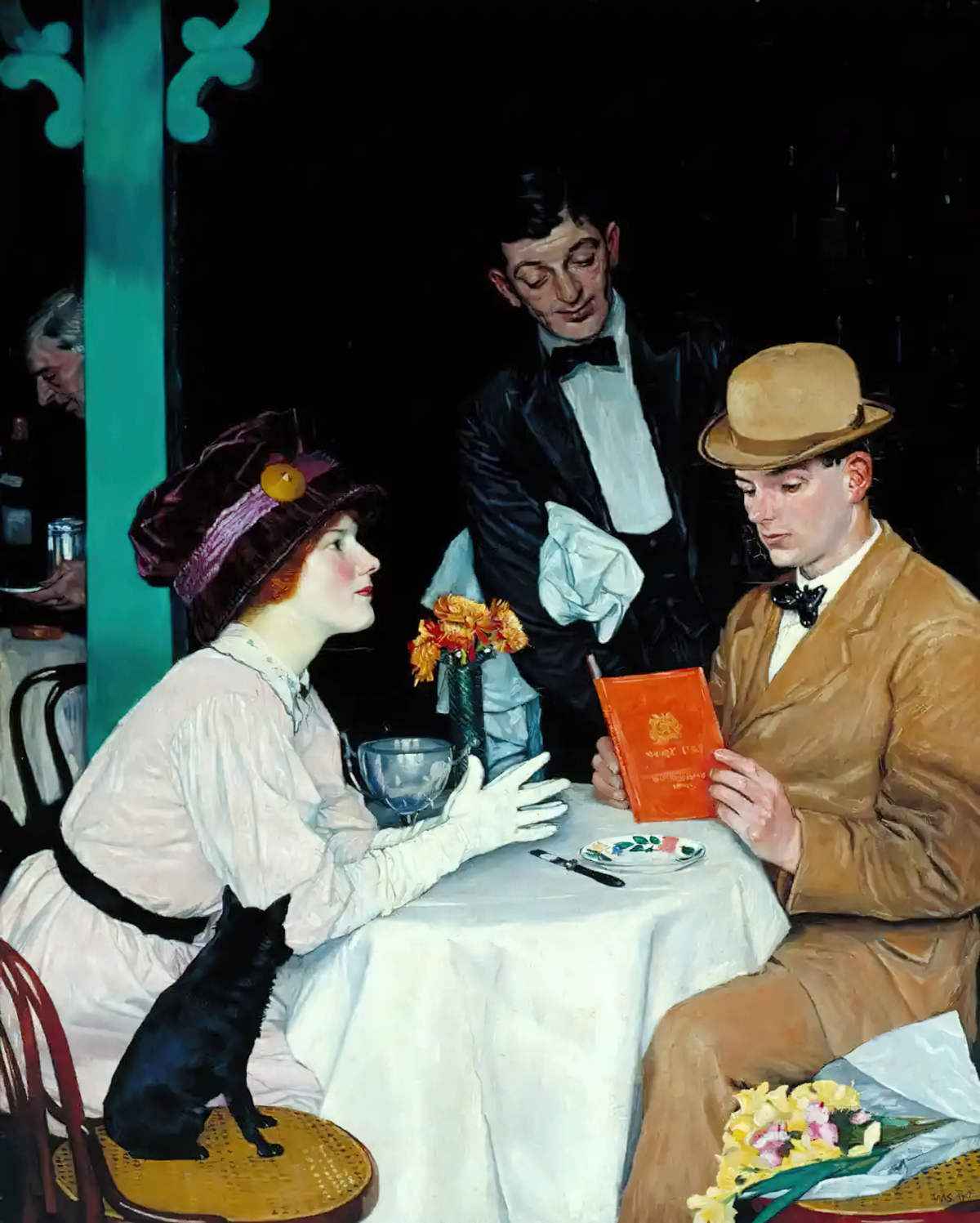

Header painting: Bank Holiday 1912 William Strang