1. What can I expect of children whose understanding of language is not yet nearly as well developed as my own adult linguistic skills, without asking too much of them?

2. What ought I to expect of children without contravening educational, psychological, moral and aesthetic requirements, particularly since it is not always easy to bring those four into line with each other?

3. And the third question, unfortunately, is: what does the market allow me, want me or forbid me to do in a rapidly developing media society?

from Comparative Children’s Literature by Emer O’Sullivan (trans. from Boie 1995)

Simply, children make the best audience. Connect with a child and you really connect. Adolescence is the same only more so.

Alan Garner, British children’s author

Writing ‘juveniles’ certainly modified my habits of composition. Thus it (a) imposed a strict limit on vocabulary (b) excluded erotic love (c) cut down reflective and analytical passages (d) led me to produce chapters of nearly equal length, for convenience in reading aloud. All these restrictions did me great good — like writing in strict metre.

C.S. Lewis

There is a place for the cliched, or conventional, plot. Children’s literature is a case in point. Perry Nodelman says,”Young readers of formula books may be learning the basic patterns that less formulaic books diverge from. Perhaps we cannot appreciate the divergences of more unusual books until we first learn these underlying patterns.”

AUTHORS AND CRITICS ON THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN WRITING FOR ADULTS AND CHILDREN

Some authors resist the idea that they are writing for the mono-audience of children and say that they instead write for everyone:

“I do not believe that I have ever written a children’s book,” the great Maurice Sendak once said in an interview. “I don’t write for children,” he told Colbert. “I write — and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’” This sentiment — the idea that designating certain types of literature as “children’s” is a choice entirely arbitrary and entirely made by adults — has since been eloquently echoed by Neil Gaiman, but isn’t, in fact, a new idea.

J.R.R. Tolkien On Fairy Tales, Language and a bunch of other things

Others prefer the idea that children are different:

Now I know there’s a theory today that we must never write for children and, after all, we’re all just big kids, but I don’t believe that. It’s partly because I refuse to think of myself as a large wrinkled child, but also because, through my children, I have come to see that childhood is a special time, that children are special, that they do not think like adults or talk like adults. And even though we adults sometimes feel that we are exactly the same as when we were ten, I think that’s because we can no longer conceive of what ten was really like, and because what we have lost, we have lost so gradually that we no longer miss it.

Betsy Byars, 1982

Pair with: The Psychology Of Your Future Self, a TED talk by Dan Gilbert

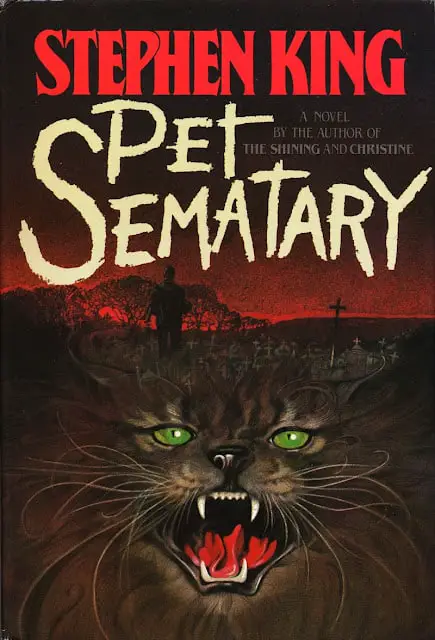

Pet Sematary by Stephen King is a horror novel R.L. Stine has said he admires. He has also borrowed the plot several times over.

When the Creeds move into a beautiful old house in rural Maine, it all seems too good to be true: physician father, beautiful wife, charming little daughter, adorable infant son-and now an idyllic home. As a family, they’ve got it all…right down to the friendly car. But the nearby woods hide a blood-chilling truth-more terrifying than death itself-and hideously more powerful. The Creeds are going to learn that sometimes dead is better.

I think it’s quite important to give children as many pegs to hang things on as possible. This is the way you learn. -So I never worry about putting in things that are not within children’s capacities, because I don’t think this matters. I think it’s very good for children to notice that there’s something going on that they don’t quite understand. This is a good feeling because it pulls you on to find out.

Wynne Jones, talking about her book Fire & Hemlock

I don’t see a clear difference between writing for children and writing for adults. It’s just that when I write for children, I’m writing for everyone; when I write for adults, I’m only writing for some people. In everything I write, I try to be ‘brief, clear, and rich’, to quote Andersen. The question ‘What is true?’ is fundamental to my life…I think of world literature as both shared and indivisible. Children’s literature is also world literature. All literature involves sharing and reciprocity, giving and receiving gifts. All works, whether they are written for children or adults, in whatever language and country, form one and same world literature, in which all works exist in relation to each other. Completely autonomous works don’t exist, and every book has many authors, both dead and alive. Literature is intellectual capital that is not used up or diminished through distribution.

Leena Krohn

I myself would hope that in my books there is no separation between comedy for children and comedy for adults. There’s just good comedy, humour in fact, because that’s a language that can speak to people of many different ages at the same time. I don’t fret over whether children can understand everything in my books. Perhaps the best situation is when they end up asking their parents and each other questions now and then – and hey presto, a literary discussion ensues.

Timo Parvela

But other children’s authors, equally widely read, say they always write with the audience age in mind:

There was much that was exactly the same in writing for a younger audience, but there were also several marked differences. The biggest that comes to mind was the way I shifted in my use of language and vocabulary. Initially it seemed awkward. In simplest terms, there were fewer words I felt I could choose from and this, in turn, presented the interesting problem of how to create a powerful story and fully realized characters without having all the tools I usually worked with.

Amy Herrick, author of The Time Fetch

My editor and I used to debate my word choices. She’d say readers wouldn’t know what a particular word meant. I would argue that we were an English language newspaper and the word was in the English language so the reader had no cause for complaint. I lost. Every time. The newspaper shot for a reading age of 11, as many do, and that was that.

The Taleist, Are You Tired Of Writing For 11 Year Olds?

The two most powerful tools for increasing vocabulary are conversation and reading. Don’t hesitate throwing in some challenging words when you converse with your children. They’ll either figure them out in context or ask you about them.

Media Darlings, Vocabulary Building Ideas For Reluctant Readers

I always know whether my reader is four or forty.

Anne Fine in an interview with Nicolette Jones

I don’t underestimate children, especially those who read a lot. They will have come across many ideas through books and through talking with intelligent people. They are more sophisticated and advanced in their thinking even though they may not be able to articulate these ideas. Just because they can’t reproduce ideas at an adult level is no reason to think they can’t take them on board.

Anne Fine

In his Harper’s essay, White mused, “It must be a lot of fun to write for children—reasonably easy work, perhaps even important work.” After Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) pointed White’s essay out to Anne Carroll Moore, she sent White a letter. If it’s so easy, why don’t you do it? “I wish to goodness you would do a real children’s book yourself,” she wrote. “I feel sure you could, if you would, and I assure you the Library Lions would roar with all their might in its praise.” (Moore often inscribed her letters with a return address of “Behind the Lions.”) White replied that he had started writing a children’s book, but was finding it difficult. “I really only go at it when I am laid up in bed, sick, and lately I have been enjoying fine health. My fears about writing for children are great—one can so easily slip into a cheap sort of whimsy or cuteness. I don’t trust myself in this treacherous field unless I am running a degree of fever.”

The Lion and the Mouse, The New Yorker

What do academic commentators have to say about children’s literature and complexity of language? Here’s a nice summary:

Current scholarship has offered analysis for some of the specific children’s texts produced by major modernist figures; however, such scholarship tends towards one of two conclusions: either the work is considered an anomaly of children’s

Happily Ever After? Ambiguous Closure in Modernist Children’s Literature

literature that would not be appropriate for any “real” child or the work is considered to be of inferior quality to texts by the same author that were intended for adults. This conclusion relies on the false assumption that children’s work can only be so complex before it ceases to be children’s literature. Sue Walsh summarizes this critical assumption in declaring that “language that is regarded as ‘arty’ is read as ‘adult’ and language that is regarded as ‘simple’ and ‘natural’ is read as ‘childlike’ and/or appropriate to the ‘child’” …. The assumption of a child’s inability to understand literary complexity has been challenged for over a century, as Sally Shuttleworth demonstrates in her detailed history of the child study movement, but its influence persists in contemporary literary criticism.

DOUBLE NARRATEES, DOUBLE IMPLIED READERS

Children’s literature academics have written about this ‘implied audience’:

… a text must “imply” a reader: that is, the subject-matter, language, allusion levels and so on clearly “write” the level of readership (it is no accident that the Pooh books, or several of Roald Dahl’s books, have proved popular with adults as well as children: the audience implied in the books is as much an adult one as a child one).

Peter Hunt, 1991

As always when speaking of children’s fiction we are dealing with a double set of codes. Unlike adult fiction, in children’s fiction we have double narratees and double implied readers. An adult writer evoking an adult reader’s nostalgia is merely one aspect. Hopefully, the child reader is targeted as well, although in a different manner.

From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature by Maria Nikolajeva

Nikolajeva argues that the difference isn’t about style (“readability”) or subject matter at all, but mainly about ‘stage of initiation described in the text’.

The fact that children’s novels seldom involve topics like sexuality, parenthood, or adultery does not depend on the subjects as such being unsuitable or tabooed, but exclusively on the problems not being relevant at the stage depicted. For young adult novels, on the contrary, sexual awakening is often the central motif. While sexual identity is relevant in idyllic fiction, it is all the more dominant at the stage of collapse.

On Amount Of Detail

It’s like a runner who’s used to doing sprints and then decides to do a marathon. When I write for kids it has to be kind of believable, but they also have to know it’s a fantasy. But when you write horror for adults, every detail has to be real. I actually had to do research on things like vegetation on the Outer Banks.

R.L. Stine, from an interview with Businessweek.

On Thematic Material

Children … have the same emotions … They may be not as complex … but as primary colours, fear is fear, happiness is happiness, and love is the same sense for a child as it is for any other.

Lloyd Alexander

Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne. All these people wrote for children. They may have pretended not to, but they did.

Ray Bradbury, explaining how these writers write ‘in metaphors’, just like he does, and that’s why their work is popular in schools.

There are some themes, some subjects, too large for adult fiction: they can only be dealt with adequately in a children’s book.

Philip Pullman

[Pullman] pours scorn on the notion that children’s books are ‘like bad books for grown-ups’, a view espoused by such luminaries as Martin Amis, Howard Jacobson and others who feel the Olympian heights of literary fiction to be polluted by adult readers reading children’s books. (As if adults and children have not enjoyed the same books, from Homer to Alice in Wonderland, for centuries.) Plenty of contemporary children read adult books, from Jane Austen to Agatha Christie and Stephen King; children’s books are written, edited and published by adults, so why should they be inferior? Why should there be segregation between older and younger readers, any more than between books for men and women, black and white, able and disabled?

Unbound

Different Life Experience

When you are writing for children, there are no cultural modifiers. No icons that you can quickly draw on for reference. You can only deal with the core emotions as that is what they recognise.

Mo Willems

The firmness of the setup must be adjusted to the target audience. We set up more prominently for youth audiences, because they’re not as story literate as middle-aged filmgoers. Bergman, for example, is difficult for the young—not because they couldn’t grasp his ideas if they were explained, but because Bergman never explains. He dramatizes his ideas subtly, using setups intended for the well-educated, socially experienced, and psychologically sophisticated.

Robert McKee, Story

The fact that something is culturally alien may not really be perceived as a stumbling-block… Children take little notice of an author’s name and do not relate to macrocontextual data. An awareness of authorship develops quite late, and the realization (not present even in many adult readers) that a translated text is in fact a translation comes even later, if at all. However, in reading — as in life — children are always being confronted by elements that they do not yet grasp and cannot understand, and so, in the process of learning to tread, if it is a successful one, young readers can develop strategies that help them to cope with such things: they skip something that is incomprehensible to them or refuse to allow minor disruptions to interrupt the flow of reading. In principle, children read texts from foreign contexts in just the same way as texts from their own cultures. We can assume that the foreign contexts are assimilated in the course of reading.

from Comparative Children’s Literature by Emer O’Sullivan

A Musical Metaphor

The craft is the same whether I’m writing children’s books or crime novels. Maybe if writing a book in the Harry Hole series, a crime novel, it may feel like conducting a symphony orchestra. Writing a children’s book is like jamming with your band. It’s more direct, but it doesn’t mean it’s easier, or less demanding. It is more enjoyable.

Jo Nesbø

Difference In Audience Criticism

Literature for children and young people finds itself wrestling with the pressures of conflicting expectations: adults think a book is a good one if they themselves genuinely enjoy it, although children often have a much more uncomplicated, hands-on relationship to reading.

Books From Finland

Difference In Subject Matter And Humour

To be honest, I don’t think I change style, genre, concepts, no matter what audiences I’m writing for. There are some subjects children probably aren’t going to be interested in: The complexities of adult relationships. There are things like farts that probably very few adults want to read about. But by and large, all my books can be read from anyone from three to adult, and I suspect they are. Just about all my work is really not age specific. I do get annoyed when people advocate limiting language for children. That’s how children learn. Language. If a book is good enough a child needs only understand four words in six and they will keep on reading. And when they come across those words another three or four times they’ll know what they mean. That is how we acquire language and concepts and so often we totally underestimate kids. Kids are often more interested in the big questions: The good and the evil and how can we change the world. Adults will often read a book because it [conforms to] their image of being intellectual. They will be more preoccupied with how you pay the mortgage and is there going to be a train strike tomorrow. But the job of a kid is to understand the world. They are deeply, desperately interested in how the world works, why, and what is good and what is evil far more often than adults. For a writer writing about good and evil, you’ve probably got a very small readership. If you are doing that for kids you have got probably everyone out there, who is passionately in what is good, what is evil and where they meet. Don’t be cute. Don’t underestimate [kids]. Don’t write down. Forget about the books that you loved as a child; always remember though who you are writing for. Don’t think of a child as being a different species. Don’t equate the words that a child is able to read with what the child is able to understand. No adult ever says to a kid ‘Don’t watch that TV show because you won’t understand it’. We say ‘No, don’t watch that TV show’ because we know they are going to understand it!

Jackie French, Australian Writers’ Centre Podcast (episode 25/10/2013)

Difference In Plot Shape

Contemporary YA novels and even novels for younger readers often come very close to adult fiction, both in their general pessimistic worldview and their complex narrative strategies. However, we can still distinguish a children’s novel from an adult novel by its unaccomplished rite of passage and its possibility of return to circularity, if only through death.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

For more on plot shapes, some of which are more prevalent in children’s literature, see Shapes Of Plots In Children’s Literature.

Difference In Relationship Between Reader And Author

A child walks into a library asking for Wimpy Kid or Artemis Fowl, not Jeff Kinney or Eoin Colfer. However, every now and then a child reader will take an interest in their favourite author and these days will be able to find information about them on the net.

THE RISE OF THE DELIBERATELY DUAL AUDIENCE BOOK

As already discussed, there aren’t as many differences between children’s books and adults’ books as you might think. Take a book such as Wonder, by R.J. Palacio:

Fans of “Wonder” say it defies categorization. “To look at ‘Wonder’ and say that’s a book for young readers is a complete disservice,” said Mr. Meltzer, who recommended the title to his 35,000-plus Twitter followers. “To me, a good book is a good book.”

Middle-grade books have become a booming publishing category, fueled in part by adult fans who read “Harry Potter” and fell in love with the genre. J.K. Rowling’s books, which sold more than 450 million copies, reintroduced millions of adults to the addictive pleasures of children’s literature and created a new class of genre-agnostic reader who will pick up anything that’s buzzy and compelling, even if it’s written for 8 year olds.

from See Grownups Read at WSJ

That said, not all books enjoyed and loved by children are equal hits with adults. There must be some very general differences, and it may be worth trying to put our finger on such differences, without resorting to an argument of worth.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR WRITERS

CHILDREN’S LITERATURE STARS YOUNG OR CHILDLIKE PROTAGONISTS

Children’s literature, as intended for an audience of children, is meant to relate to the interests of children. Not surprisingly, then, its central characters are children— or at least, childlike creatures. Although many of the versions of the generic story…are about humanized objects or animals, their main characters are often described as being young and, in that way, equivalent to the children who read about them.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Nodelman and Reimer explain that, often, ‘these children or childlike characters confirm adult assumptions about children. They are limited’. Authors are fond of telling children that they’re too limited to cope with the big wide world on their own. Tales for children often praise innocence and ignorance (the youngest of three brothers wins out, the Cinderellas end up married to princes), everything Winnie the Poo does is funny and adorable. Olivia the pig is the same.

Generally, children’s books featuring innocent characters fall into one of two categories: Either the innocence is adorable, or puts the character in danger. The climax of the second kind of innocent character happens when the character realises the extent of their own innocence and gains sufficient knowledge to get out of the storyline problem. The message is therefore: All children must lose their innocence at some point.

ENDINGS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE MUST CONTAIN SOME SENSE OF HOPE

This seems to be an unwritten rule of children’s literature, since you’ll be hard-pressed to find a popular children’s book with an entirely hopeless ending for the main character.

Many characters in children’s novels who flee from broken or disrupted homes…encounter bitter experience but still manage to avoid cynicism by finding new homes where they can preserve their innocence and optimism.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Lissa Paul has said that the main difference between children’s stories and women’s fiction (specifically, as it is marketed) is the ending. Women remain entrapped in women’s novels while children are more likely to escape their entrapments. In this way, children’s novels are more forward-thinking than women’s novels — ahead of the change rather than reflecting the status quo.

So when Jon Klassen wrote This Is Not My Hat, the ending shocked many people.

THE HOME-AWAY-HOME PATTERN IS PREVALENT IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Adult fiction that deals with young people who leave home usually ends with them choosing to stay away. As the adult novelist Thomas Wolfe suggested in the title of one of his books, “You can’t go home again.” But[…]characters in texts of children’s fiction tend to learn the value of home by losing it and then finding it again. This home/away/home pattern is the most common storyline in children’s literature. As Christopher Clausen says, “When home is a privileged place, exempt from the most serious problems of life and civilization—when home is where we ought, on the whole, to stay—we are probably dealing with a story for children. When home is the chief place from which we must escape, either to grow up or…to remain innocent, then we are involved in a story for adolescents or adults.”

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Nodelman and Reimer add that:

1. Stories in which escape from home leads to growing up are usually for adults.

2. Stories for which escape allows for the preservation of some form of innocence tend to be for adolescents.

They also break down the binary differences that tend to crop up in home-away-home stories for children:

- Human-animal

- Adult-child

- Maturity-childishness

- Civilization-nature

- Restraint-wildness

- Clothing-Nakedness

- Obedience-disobedience

- Imprisonment-freedom (the vast majority of all stories have an imprisonment-greater imprisonment-freedom arc.)

- Boredom-adventure

- Safety-danger (any Home-Away-Home story in which home is a refuge, though even Harry Potter returns ‘home’ to The Dursleys at the end of each book.)

- Calm-excitement

- Acceptance-defiance

Thematically:

- Common sense-imagination

- Sense-nonsense

- Cynicism-wise innocence

- Wisdom-ignorance

- Old ideas-new ideas

- Past practice-future potential

- Custom-anarchy

- Conservatism-innovation

- Fable-fairy tale

- Reality-fantasy

- False vision-reality

- Good-evil

- Evil-good

More modern readers are hoping for a different kind of story than the home-away-home structure and its variations, wishing for a new emphasis on:

- Wholeness

- Interdependence

- Relationship

So if you’d like to write a children’s story that hasn’t been done many times before, it might be worth examining those words and trying to work out exactly what it would mean to create such a story.

Maria Nikolajeva says that the main influence on children’s literature are all the children’s stories that have come before — because the home-away-home pattern is so dominant, for instance, this makes the reader expect a certain thing from a book, and so authors who write stories to fit this pattern are rewarded in sales. Once a type of story gets established, it tends to stay there, perhaps even more so in children’s literature than in adults’ literature, in which the adult reader is given the credit of knowing what they like regardless of its unconventionality.

THERE IS A MORE OBVIOUS IMAGE SYSTEM IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Outside certain highly symbolic genres in adult fiction ie. Westerns, science fiction, children’s books tend to have more ‘obvious’ symbolism, but that’s only because as adults we’ve already learned to read the symbols. We all had to learn image systems at some point.

An image system refers to all the symbols, motifs and imagery that occur throughout a work. An image system must be subliminal for the audience, or else it doesn’t work because it calls attention to itself. When Sixth Sense made use of the colour red as a recurring motif throughout the film it felt new and a bit edgy to lots of the audience, but this has been used many times since, so that by the time We Need To Talk About Kevin was adapted for the screen, adult audiences were used to seeing the colour red used in this way, and therefore it wasn’t quite as effective for sophisticated viewers.

We Need To Talk About Kevin

The Omen (2006)

By the time this film came out, a lot of avid adult cinephiles were sick to death of all the heavyhanded red:

And can someone PLEASE issue a public memo to every working director that the use of the color red to “convey danger” is the most overdone, tired cliché in the universe? Ever since Spielberg spoke about removing red from Jaws until the second attack (to make the red seem redder, not to “mean” anything), uncreative filmmakers think that using red to “signify” (read: insult your audience’s intelligence) is the height of intellectual filmmaking. Please. In this case, it’s so heavy-handed that it’s laughable – the staggering number of red balloons that were used in the film is more frightening than the movie itself. This John Moore and M. Night Shyamalan need to go off and give each other massages and then scream with their arms spread open to the sky or something.

Camp Blood

Robert McKee, in his book Story, is scathing of adult films which ‘name’ their symbolism. He mentions The Piano, the remake of Cape Fear and Bram Stoker’s Dracula as particularly bad offenders, then goes on to explain the heavy symbolism in films for adults:

First, to flatter the elite audience of self-perceived intellectuals that watches at a safe, unemotional distance while collecting ammunition for the postfilm ritual of cafe criticism. Second, to influence, if not control, critics and the reviews they writes. Declamatory symbolism requires no genius, just egotism ignited by misreadings of Jung and Derrida. It is a vanity that demeans and corrupts the art.

In a review of an episode of Mad Men — in which the sex scenes alone designate this a TV series only for adults — Slate’s TV critic Willa Paskin writes:

As for that scene with Neve Campbell: I’m afraid that my bullshit meter started ringing right about the time she confessed that her husband “died of thirst,” one of those Please, take out your highlighter and identify the big theme in the text bits of dialogue Matthew Weiner sometimes can’t stop himself from writing.

But remember that a TV critic with ink in Slate is the among the most sophisticated of viewers. Not all adults want to put in the work necessary to decoding imagery in a story.

Children, on the other hand, have simply not had the experience of story, and will not be affected by slightly heavy-handed image systems — or ‘declamatory symbolism’, as McKee calls it, because they simply have had not many years in which to become weary of the same sorts of literary techniques. That said, with heavy media exposure they quickly learn the tricks, and it’s better to over-estimate their sophistication if in doubt.

THERE ARE MORE IDEOLOGICAL CLOSURES IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

(DUE TO IDEAS ABOUT CHILDHOOD ABILITY TO FILL IN GAPS)

A conclusion [of a story] does not necessarily entail…ideological closure, and many contemporary works feature deliberately open conclusions which allow the reader freedom to interpret them while implying uncertainty as a universal principle….While open endings in adult literature are now common it is often argued, on the basis of Piagetian theories of child development, that young children need stories with clear cut distinctions between right and wrong and satisfying conclusions. Some popular contemporary picture books, however, suggest that eve quite young children are able to construct meanings from texts which contain significant gaps and avoid rigid ideological closure. (e.g. John Brown, Rose and the Midnight Cat by Jenny Wagner, in which readers must construct interpretations on their own.) … The brief texts of picture books are perhaps inevitably more open than longer works but open endings which refuse ideological closure are now also no longer unusual in children’s novels.

from Deconstructing The Hero, by Marjery Hourihan

Hourihan points out that narrative conclusions are different from ideological conclusions — no matter how much is left to the reader’s interpretation, the story must still ‘feel’ complete to the reader. For examples of strong ideological tales, refer to most hero stories, with their central binary oppositions (goodies and baddies) in which the goodies ‘win’.

But as Francis Spufford says,

No book is truly open-ended. Ask any deconstructionist: they’ll tell you that a fictional text, however wide it spreads its net, is a closed system within which possible interpretations are carefully limited and managed. But there is still a great difference in sensation, for the reader, between a story that is explicitly story-shaped, following visible and external rules like the rule of a happy ending, and one that takes advantage of the novel’s great freedom to flow into any form at all that embodies the author’s sense of the internal order of their material. I was not yet willing, or able, to see the ad hoc shapes of adult novels. I still needed the given forms, the definite outlines of children’s books.

The Child That Books Built

CLEARER DELINEATION BETWEEN GOOD AND EVIL

Describing the period in which he started reading books for adults as an adolescent, Francis Spufford writes:

I was…puzzled by the strange silence of authors about their characters. Oh, they described them, all right — but who was good? Who was bad? What was I supposed to think about them? I was used to the structure of a fictional world being a structure of judgments, an edifice built to provide you with a moral experience in exactly the same way that it brought you tastes, smells and sights. I expected to be guided. I thought that reading was intrinsically a bargain in which you turned off your own powers of judgement and let thea uthor’s take over, so he or she could show you a pattern made by the interplay of some people who were exactly what the author said they were. The point of stories to me was that the people could be decisively known in them. The author’s special intimacy with them unmasked them for the reader; or rather, turned them so that you saw exactly the moral facets of them that the story needed.

The Child That Books Built

In a somewhat ironically written response to Kent University last year suggesting on their website that children’s literature is not real literature, Jonathan Myerson writes:

[The difference between adult fiction and children’s fiction] isn’t about the quality of the prose: the best children’s books are better structured and written than many adult works. Nor is it about imaginary worlds – among the Lit Gang, for instance, Kazuo Ishiguro, Cormac McCarthy and Michael Chabon have all created plenty of those. It’s simpler than that: a novel written for children omits certain adult-world elements which you would expect to find in a novel aimed squarely at grown-up readers.

He then explains that books — whether intended for adults or children — appeal better to children when good and evil is clearcut:

When I was a “young adult”, YA fiction didn’t exist and I filled my hours with Robert Louis Stevenson or Isaac Asimov. These novels held and excited us because they created scenarios where good and evil were clearly defined and rarely muddied.

(Note that Isaac Asimov is not generally considered a writer of children’s fiction. Yet I’m sure plenty of boys — in particular — found Asimov in their teenage years.)

Myserson goes on to explain:

I am so glad that first-rate children’s literature was there for my own children. I would not have wanted them – at 11, 12 or 13 – to confront the complexity and banality of evil. It’s quite right that they wanted to read about worlds where evil was uniformly evil and good people were constantly good. In contrast, adulthood means learning that SS officers or drone pilots do go home and kiss their wives, without a thought of belonging to the “dark side”. Equally, while you come to know how to interpret Portnoy’s self-loathing or Humbert Humbert’s witty detachment, children wouldn’t enjoy these characters or their dilemmas. The best young adult novels do bridge that sticky chasm between the undoubting days of childhood and the hedged decades of adulthood.

CERTAIN ADULT SUBJECT MATTER IS LEFT OUT OR HIDDEN

Of the three principal preoccupations of adult fiction—sex, money, and death—the first is absent from classic children’s literature and the other two either absent or much muted.

Alison Lurie

Myseron’s article leads on to the next main difference between fiction for adults and fiction for children:

Great adult literature aims to confront the full range of genuine human experience, a world where individuals do not wear the same black or white hat every day. Life is messy, life is surprising and, most of all, life is full of compromises. One of the great themes of literature – which therefore often makes for great literature – springs from the protagonist who rejects compromise and usually pays the price (Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina, Pinkie Brown, Rabbit Angstrom). Would we really want our children to cope with the unwinnable dilemmas of JM Coetzee’s Disgrace? …[A novel for children] is simply a novel which leaves something out.

I’d like to add that some of the most sophisticated writing ‘for children’ in fact manages to appeal to an adult audience equally, and this is achieved by layering meaning, hiding difficult subject matter in such a way that a reader won’t find it at all unless already at the stage where it’s able to be dealt with. Kristopher Jansma writes in an article titled ‘Why Children’s Books Matter’ of his experience reading Peter Pan:

After Josh was born, we moved on to Peter Pan, which is delightfully dark and death-obsessed, with complex psychological concerns. Peter cannot form lasting memories because then he might learn from them, and thus, like the rest of us, grow-up. At several points he forgets he has killed someone. He can neither return Wendy’s pre-teen affections nor understand Tiger Lily’s advances after he saves her from drowning. “There is something she wants to be to me, but she says it is not my mother,” he complains to Wendy. Like Peter, younger readers wouldn’t get this; it’s clearly a joke meant just for the adults. Similarly, their little hearts don’t break like mine did when, at the end of the book, Wendy asks Peter about Tinker Bell—the fairy who drank Captain Hook’s poison to save the hero’s life. Peter shrugs. “Who is Tinker Bell?” he asks.

Reading these books each night I cannot get over how grown-up they feel.

In another response to the same Kent University incident, Phillip Pullman writes:

The books I read as a child shaped my deepest beliefs. When I was at university, my friends and I were thrilled to discover that our childhood favourites seemed even more powerful than we remembered. This was true of classic authors such as George MacDonald, Rudyard Kipling, E Nesbit and Tove Jansson; or 1960s writers like Alan Garner, Susan Cooper, Peter Dickinson and Ursula Le Guin.

In the work of such authors, we found stories that were compelling and readable; that had depth, risk and originality; that offered all the imaginative space and possibilities we wanted from literature. Garner and Cooper made connections between ancient myth and contemporary reality; Dickinson dealt with human origins, with politics and war; Le Guin with the interconnectedness of all life. These books were tackling the biggest ideas and questions imaginable.

So rather than ‘leaving certain content out’ it would be more accurate to say that writers of children’s literature are masters hide-and-seek, carefully layering meaning so as not to cause irreparable damage to impressionable young minds, while at the same time not boring adult co-readers to tears.

NECESSARY PREDICTABILITY IN TEXTS FOR EMERGENT READERS

And when I say ’emergent readers’ I’m not just talking about decoding of the words, but of story structure itself. This is why certain types of predictable story structures bridge a gap between not reading and reading books designed for an older, wider audience.

Predictable Books

Predictable books, also called pattern books, are stories that feature repeated language patterns — repetition of words, phrases, sentences, and refrains — throughout the text. Particular phrases with strong rhyming and rhythm create a predictable text that propels the story forward. Illustrations feature repeated elements and backgrounds that create continuity. Brown Bear, Brown Bear (1967) is probably the most famous predictable title. The text begins with the phrase, “Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see? I see a red bird looking at me. ” In each successive page the animal from the second sentence is moved to the beginning of the next sentence (e.g., “Red bird, red bird, what do you see? I see a yellow duck looking at me,” and so forth.) Predictable books invite children to make predictions about upcoming textual elements (words, phrases, and sentences) and pictorial elements (line, shape, color, value, texture, and space).

From A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and using picture books

Matulka then categorises the different types of predictable children’s books:

- Chain or circular stories — Why Mosquitoes Buzz In People’s Ears, Oh, Look!, If You Give A Mouse A Cookie

- Cumulative stories — Hattie and the Fox, Mr Gumpy’s Outing, One Fine Day

- Familiar sequences — Today Is Monday, Chicken Soup With Rice

- Pattern stories — The Doorbell Rang, The Runaway Bunny, The Carrot Seed, Suddenly!, Where Is The Green Sheep?

- Question and answer stories — Brown Bear, Brown Bear, Where Is The Green Sheep?, What Do You Do With A Tail Like This?, Knock! Knock!

- Repetition of phrase — Bear Snores On, Hug, No, David!, It Looked Like Spilt Milk, Silly Sally

- Rhyme — Sheep In A Jeep, Barnyard Banter, Is Your Mama A Llama, Hairy Maclary From Donaldson’s Dairy

- Songbooks — Over In The Meadow, Farmer In The Dell, Old MacDonald Had A Farm

When these structures exist in books aimed at adults, they do so hoping to evoke childhood, either ironically or as part of a childhood-related theme.

MORE LIMITED WORD CHOICE

There are two opposing views on whether word choice should be limited when writing for children. Some people believe that of course word choice should be somewhat limited in books that are specifically graded for children who are learning to read, but that once children have learnt to read, then the full range of adult vocabulary can be used. The question is: How do we know when the average child of your book’s audience has ‘learnt to read’?

E.B. White did not believe in modifying language for children:

Anyone who writes down to children is simply wasting his time … Some writers deliberately avoid using words they think the child doesn’t know. This emasculates the prose, and, I suspect, bores the reader. Children are game for anything. They love words that give them a hard time, provided they are in a context that absorbs their attention.

E.B. White, children’s author and expert on style

A writer … should feel himself no more under the necessity to restrict the complexity of his plotting because of differences in child understanding … than he feels the necessity of restricting his vocabulary.

Eleanor Cameron, children’s author and critic

Others consider a more limited word choice in children’s stories a kind of high art form:

The children’s book presents a technically more difficult, technically more interesting problem — that of making a fully serious adult statement, as a good novel of any kind does, and making it utterly simple and transparent … The need for comprehensibility imposes an emotional obliqueness, an indirection of approach, which like elision and partial statement in poetry is often a source of aesthetic power.

Jill Paton Walsh, who writes for both children and adults

Some writers use short staccato sentences believing that such sentences are easier to read, but they’re not necessarily.

Obviously, repetitive prose that builds upon itself is a feature of children’s books rather than adult books, unless the adult books are a parody of something.

MORE CONCRETIZABLE DESCRIPTIONS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

In literacy terms, ‘concretizable’ means that the reader is able to see something which is described in words. It is thought that children need to be able to do this in order to understand a text, though adult readers may lose the need, and therefore the ability to do this so vividly.

The ways in which texts written for children describe their characters and settings can be explored by studying two different but connected qualities. One relates to the characteristic kinds of language in the texts and the rhythms that their language creates…The first and most obvious thing to be said is that the description presented is characteristically minimal—at least, in relation to the more complex and more textured descriptions found in many texts written for adults. But the sparseness of descriptive language does not make these texts vague. The information offered tends to be concrete rather than abstract—to give specific details about shape, sound, and color that allow readers to imagine physically specific worlds. In Joey Pigza Loses Control, for instance, Joey provides not just the abstract information that his mother is ‘stressed-out’ but also some easily visualizable details: “Her elbos were shaking and her jaw was so tight her front teeth were denting her lower lip”. The texts of picture books tend to leave out visualizable details of this sort—but do so for the obvious reason that the pictures in them offer equivalently concrete and visualizable information about the way things look. […] It might even be argued that picture books offer readers actual visual information as an apprenticeship in learning how to imagine it for themselves, anticipating the act of concretizing information in the novels they’ll read later that lack actual pictures.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

CHILDREN’S STORIES TEND TO BE MORE DIDACTIC

Telling a didactic story when writing for modern adults is a big no-no.

Cheryl Klein argues that contemporary stories for children and adults are equally complex:

If you study the history of children’s literature, it begins with morality tales. There’s a set of German children’s stories called Struwwelpeter about little Peter, who wouldn’t cut his fingernails or his hair, and Pauline, who burnt herself up by playing with matches. But as children’s fiction has evolved through the last hundred and fifty years or so, it’s taken on the literary and psychological complexity that adult fiction has had for centuries, away from the moral and heavy-handed, toward the complex, the nuanced, the real.

But in stories for children, though overt didacticism has gone the way of the do-do, you could argue it’s still there… as it is there in stories for adults.

As its focus on new and unfamiliar experiences reveals, children’s literature wouldn’t exist at all if adults didn’t see children as inexperienced and in need of knowledge. Its stories typically show children who are relatively new citizens of the world they inhabit, and in the process of learning about it, so that adults can use the literature as a means of teaching these newcomers about that world. Children’s literature is almost always didactic: its purpose is to instruct.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

But Nodelman and Reimer describe a different kind of children’s story which is not didactic but still quite obviously for children:

On the other hand, some texts are less concerned with telling children what they should be than with giving them what adults assume they already want and like to hear. On TV and in written texts, consequently, much popular storytelling has little to say about the safety of home and much to say about the delightful freedom of being away from home. Goodness consists of the presumably childlike values represented by being away from home.

The big-prize winning modern texts and texts which become classics tend to be ambivalent rather than didactic. Reimer and Nodelman offer Where The Wild Things as an example. I will add picture books by Jon Klassen, in which the morality of the thieving creatures seems (at first glance) to go unpunished.

Indeed,

A noticeable feature of some major ‘classic’ children’s books is that they text and undermine some of the values which they superficially appear to be celebrating.

Peter Hollindale

SETTINGS TEND TO BE THOSE FAMILIAR TO CHILDREN—HOMELIKE

There is also the question of the spaces most characteristically described in children’s literature—where they are set. Not illogically, many texts for children take place in settings that children typically occupy: homes and schools, beaches and campgrounds, and so on. Beyond that, however, there is no particularly characteristic group of settings. Well-known texts are set in places as diverse as farmyards and castles, medieval forests and contemporary inner-city slums, and a whole range of imaginary fantasy settings from Narnia to Oz to the infinite alternative worlds of Philip Pullman’s Golden Compass and Subtle Knife. What is characteristic about the places described in children’s literature is the extent to which the texts clearly identify some of them as a central character’s home—or at least as being homelike—and some as not being home or homelike.

The Pleasures Of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

About every Goosebumps book has to take place in some kid’s backyard, or the kitchen, or the basement. It’s scarier for kids if it starts in their own house or neighborhood. Some writers make a mistake; they want to do something creepy, so they pick a huge dark castle in Europe, but kids don’t relate to that.

interview with R.L. Stein at Neatorama

INTERTEXTUALITY IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS VS BOOKS FOR ADULTS

This is more to do with the way children’s literature is received than how it actually is, but

Intertextuality is one of the most prominent features of postmodern literature for adults, and critics have proclaimed it both welcome and indispensable. In children’s literature most intertextual links are often approached as imitative and secondary.

Maria Nikolajeva, Children’s Literature Comes Of Age

Intertextuality makes use of the literature which has come before, often building on it, at the least inspired by it. That Bakhtin fellow prefers the term ‘dialogics’. Whatever it is called, the meaning of a text is revealed for the reader/researcher only against the background of previous texts. Whereas ‘comparative literature’ is concerned with how one text has ‘influenced’ the other, an intertextual study considers the two texts as equal.

In children’s literature, intertextuality is often apparent in the use of:

- allusions

- irony

- parody

- direct quotations

- indirect references

- and the fracturing of well-known patterns.

THE PASTORAL IDYLL

What does ‘pastoral’ mean?

In classic children’s fiction a pastoral convention is maintained. It is assumed that the world of childhood is simpler and more natural than that of adults, and that children, though they may have faults, are essentially good or at least capable of becoming so.

Alison Lurie, The Subversive Power Of Children’s Literature

But the idealised worlds of children’s books are really no different from the ‘pastoral idyll’ of many books for adults. The ‘pastoral idyll’ is a form of poem that celebrates the joys of the unsophisticated rural life, close to nature and in the company of friends. The pastoral idyll may explain the success of The Pioneer Woman cooking shows, or even Downton Abbey and many cosy murder mysteries popular today. In children’s literature we have

- Wind In The Willows — making potentially disturbing events seem safe by placing them within an innocent pastoral milieu

- The Secret Garden — an example of an actual garden, along with Tom’s Midnight Garden

- Anne of Green Gables — a rural backwater where everyone knows everyone’s business

- Where The Wild Things Are — a forest

- A River Dream — features a peaceful river, along with Swallows and Amazons

The urban equivalent of this pastoral idyll is perhaps a treehouse, a backyard hideaway. We have suburbs of the kind where Ramona Quimby grows up, which provide a safe backdrop for minor dramas.

The pastoral idyll is a nostalgic form of literature, and young adult fiction is currently going through a backlash, with extremely dark plots as a way for young readers to make sense of their own (hopefully more minor) issues.

Children’s books tend to try to persuade children that adult nostalgia is actual current childhood experience—that the world is in fact as idyllic as children’s books suggest. […] Although children’s literature is written from the viewpoint of what adults imagine is innocence…it does not necessarily postulate an innocent or uncomplicated world. In less interesting children’s books, writers create idylls by simply leaving things out…But in more interesting books, the ironies are internal and deliberate, and the result is an ambivalence about the relative values of innocence and experience, the idyllic and the mundane.

Nodelman and Reimer

FURTHER READING

Intertextuality in Children’s Books vs Books For Adults

Celebrating Picture Books: Not just for kids, from SLJ

Why it’s time to lay the stereotype of the ‘teen brain’ to rest from The Conversation

Header painting: George Goodwin Kilburne – Mother and Daughter