Story is the chronological order readers discover when they ask “what happened next”?

Plot is the order readers experience when they pay attention to what happens next as they read. Plotting is what storytellers do when making decisions about how to unravel their story. Storytellers don’t tell the entire story. They pull out the interesting bits from the narrative which exists in a more complete form inside their heads, and in the writing (or editing) of the story, give readers the illusion of contiguity.

Suspense is what you call the tension between discovering the story and experiencing the plot.

Plots are effective — everyone wants to know what happens next — but the denouement of plot-driven novels is often implausible and disappointing. Is that all it was? This is because there are no plots in real life — only a complex web of continuum and connexity — so the reader has the unpleasant sensation of having been conned. And plots are instantly forgettable. Try explaining the plot of the thriller you read only last week. The pleasure of plot is all expectation and sensation, illusory and short-lived, so plot-driven novels leave no residue of beauty. Whereas a novel that reproduces the texture and feeling of life will be harder to read, but provide richer satisfactions and live longer in the memory. The bad news is that such novels are rare. Proust and Joyce showed how to succeed triumphantly without plot but this lesson has been forgotten by the age of potential. It is common now for reviewers to rate novels as ‘well-plotted’ or ‘poorly plotted’, as though plot is an essential feature, and to express astonishment and consternation at the absence of plot.

Michael Foley

I’ve often noticed that we are not able to look at what we have in front of us, unless it’s inside a frame.

Abbas Kiarostami

STORY AND DISCOURSE

It is writers who think in terms of story versus plot. Critics tend to think in terms of story versus discourse. Story refers to the chronological sequence of events in a narrative. Discourse refers to the re-representation of those events (all the various ways the story is told). Discourse includes plotting but also refers to wider aspects of narration, metaphors and other imagery. Rather than talk about ‘plotting’ they might talk about a ‘re-ordering of the temporal sequence’. On screen, analysis of discourse will include camera angles and all the other cinematic techniques.

FABULA AND SJUZHET

The words Fabula and Sjuzhet basically line up with English ‘story’ and ‘discourse’ respectively.

The terms come from Russian Formalists, an influential group of structuralists.

SPATIAL FORM

Not all stories have plots. Lyrical short stories are sometimes called ‘plotless’. Plots are highly encouraged if you’re writing for a wide audience, but as Michael Foley writes in his book The Age of Absurdity, stories with plots have a downside. He’s basically describing the ideology of the Literary Impressionists:

More than any other narrative structure, the short story veers toward what Joseph Frank calls “spatial form” — a set of narrative techniques and processes of aesthetic perception that work to impede linearity. For most novels scale is weighted on the side of everyday reality, measured by means of accumulation of matter-of-fact details within temporal frames. But short stories are kind of the opposite: Elements of the mythic and dreamlike are foregrounded. Instead of moving through time in such a way that propels readers on, readers of short stories are catapaulted from beginning to end and back again. Short stories are designed to be re-read.

Mary Rohrberger, The Art of Brevity

The central problem, says C.S. Lewis, is that for stories to be stories, they must be a series of events; yet at the same time it must be understood that this series is only a net to catch something else. And this “something else” has no sequence in it; it is “something other than a process and much more like a state or quality.” The result is that the means of fiction are always at war with its end. Lewis says, “In real life, as in a story, something must happen. That is just the trouble. We grasp at a state and find only a succession of events in which the state is never quite embodied.”

How does a writer convert mere events — one thing after another — into significance? This raises the additional problem that even as writers encourage the reader to keep turning pages to find out what happens next, they must make the poor reader understand that ultimately what happens next is not what is important. This basic incompatibility, which has been noted by many critics, is much more obvious in the short narrative (which, in its frequent focus on a frozen moment in time, seems atemporal) than the long narrative (which seems primarily just a matter of one thing after another).

Although authors want to communicate that which is instantaneous or timeless, they are always trapped by the timebound nature of words.

Charles E. May, The Art of Brevity

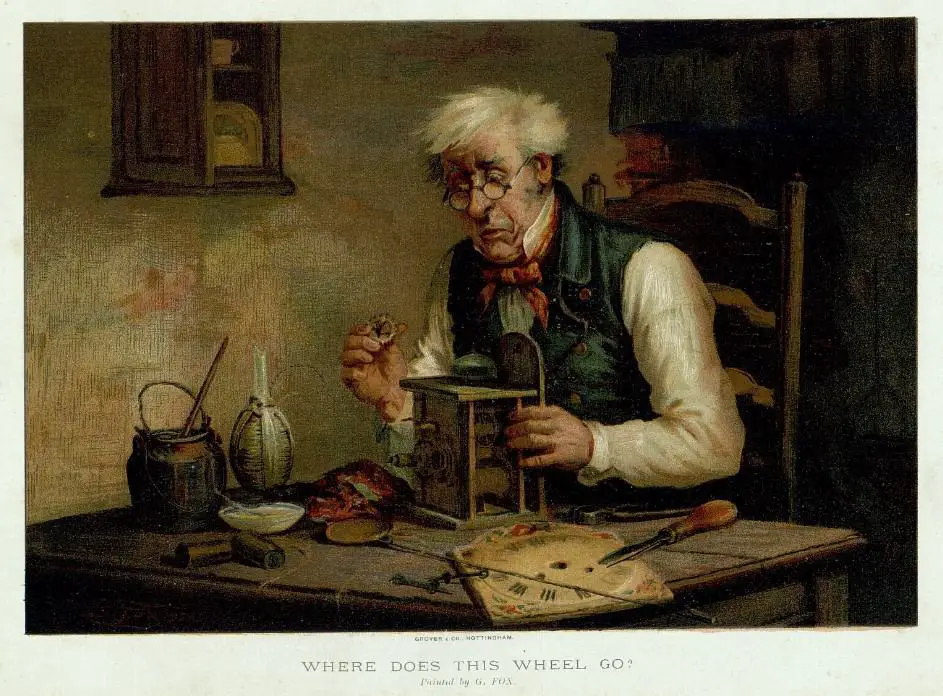

Header painting: Lee Lufkin Kaula — Mother Reading with Two Girls