This month I wrote a post on Teaching Kids How To Structure A Story. Today I continue with a selection of mentor texts to help kids see how it works. Yesterday I analysed the structure of an Australian bush ballad. Today I stay in Australia, with the modern picture book classic Diary of a Wombat by Jackie French and Bruce Whatley.

Like Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Diary of a Wombat is a parody of a diary. We expect that if someone has taken the trouble to write something down then it must be something important. But wombats don’t really do much and have little to report. Jackie French could have anthropomorphised the wombat and taken her off on an adventure to save the world, but this wombat is inspired by the wombats around French’s own house. Bruce Whatley illustrates animals in a mostly realistic style, with only a few modifications to make the facial expressions more human, making the pairing perfect.

STORY STRUCTURE OF DIARY OF A WOMBAT

WHO IS THE MAIN CHARACTER?

The wombat.

Unusually for a children’s book, the wombat is female yet has not been given any typically feminine markers, such as a big pink bow. This is partly to do with the realistic style of art. (There is no obvious sexual dimorphism in wombats — you can’t easily tell the sex of a wombat unless you’re an expert.) I wonder if you assumed the wombat was male until “For Pete’s sake! Give her some carrots!” A study by Janet McCabe told us that unless animal characters are given obvious female markers then we tend to read them as male.

The wombat hasn’t been given a name. Often this is because a character stands in for a group. In this case, she stands for your typical wombat, doing typical wombatty things.

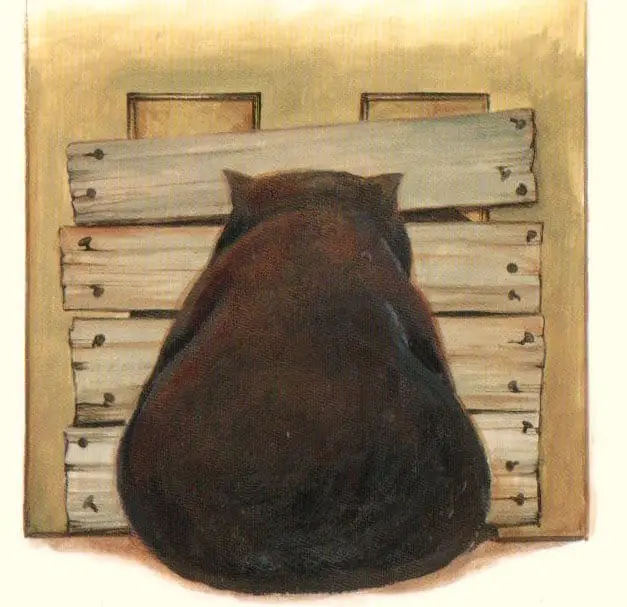

A standout feature of the wombat is the distinctive round bottom, which may be why Bruce Whatley chose to depict the wombat from behind in a number of illustrations. This is surprisingly uncommon for picture books, in which we’re more likely to see ‘posed for a photo‘ characters. Bruce Whatley doesn’t vary the top-bottom angle of the wombat, keeping to one-point perspective throughout, without making use of high/low angles. This allows the reader to remain right alongside the wombat as an equal at all times. His choice to depict the wombat in various cardinal directions may partly be to do with the need to vary each illustration from the others. But when wombat sits and stars at the boarded-up door, we really feel her petulant patience for carrots, even though we can’t see her face.

The choice is masterful.

What is wrong with her?

Since our main character a wombat she is unable to communicate what she wants to the humans. This is one of the reasons animals are so common in picture books. They are like young children, also unable to communicate what they need in words.

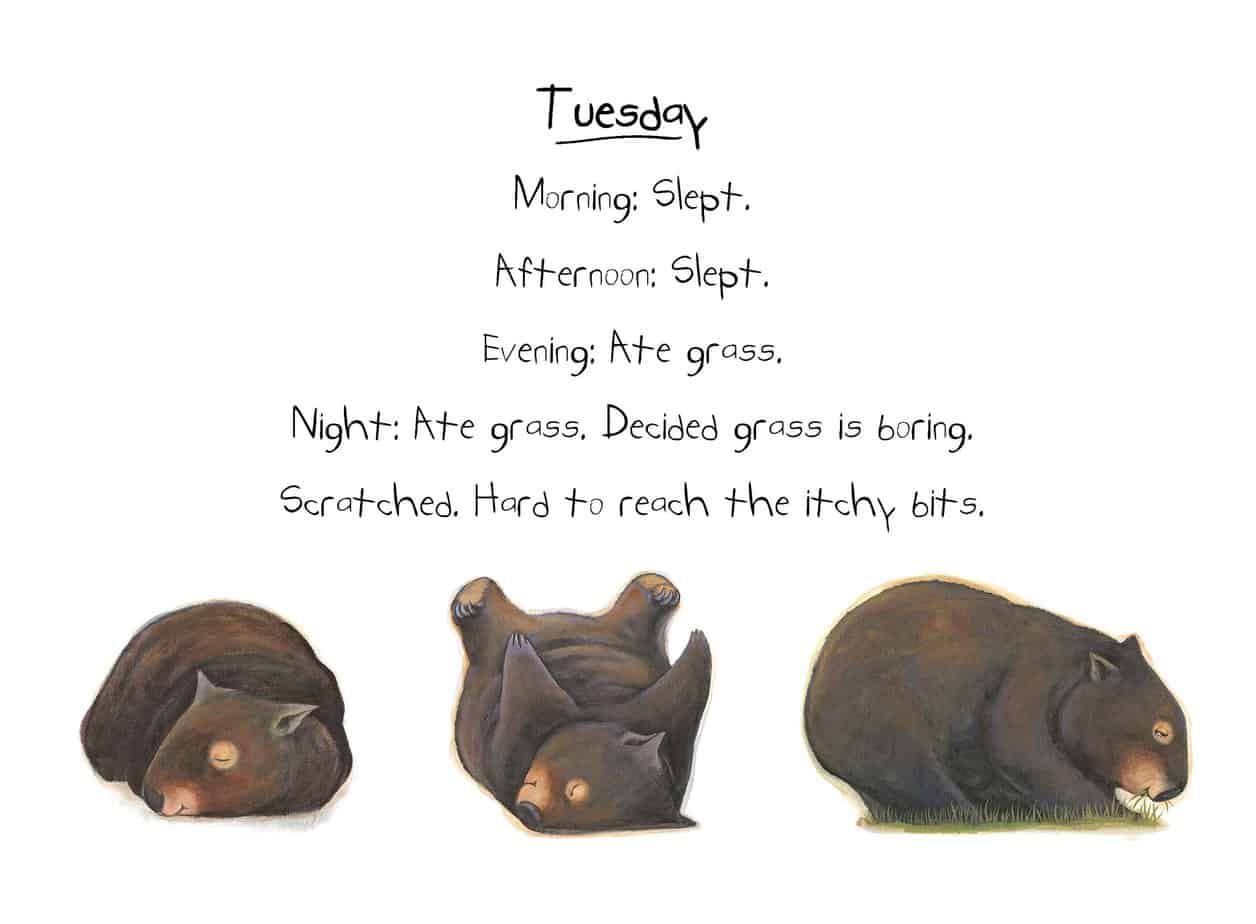

She is also capricious and according to typical human work ethic, she’s comically lazy.

This is an oblivious character who doesn’t see the havoc she wreaks behind her. She doesn’t realise the humans filled up her hole because they didn’t want a hole. Unlike Peter Rabbit, she doesn’t realise the carrots in the garden have been planted there by someone and that she thieved them. She thinks she happened upon them.

WHAT DOES SHE WANT?

The wombat has simple needs and lives in a wombat utopia — a rural human environment with a large supply of carrots growing in the garden, good soil for digging holes and everything else she could possibly want. The wombat’s stand-out feature is that she wants for nothing. But for narrative drive, a story requires that the main character want something.

Jackie French has fulfilled this story step by giving our wombat the strong desire for carrots. Not only that, she is endlessly greedy for carrots and even when given carrots, she still wants more. This desire drives most of the story but, comically, she eventually has enough of carrots and decides she wants rolled oats instead. This is where her main shortcoming comes in: she is unable to tell the humans that she now wants rolled oats.

By the way, comic characters often have insatiable appetites. In a comedy ensemble you’ll usually get one who is obsessed with food.

- In Kath and Kim, Kim is always eating. (Sharon stress eats as well.)

- In Seinfeld it’s Kramer who is always going to Jerry’s for cereal and whatnot. He is shown to be a fruit connoisseur, and in another episode the big gag is that Kramer could have won a lot of money after being scalded by hot coffee, but he is delighted with a lifetime’s supply of free coffees instead.

- In The Simpsons, Homer is the character who represents the stomach.

Characters are also funny if we can laugh at their stupidity. The obliviousness of the wombat means that Jackie French created her loosely based upon the classic Dolt character. There are many different comedy character archetypes. Here are a few more.

OPPONENT/MONSTER/BADDIE/ENEMY/FRENEMY

The human family are in opposition to the wombat not because the humans are trying to get rid of her, but because they have different goals which cannot coexist:

- Family wants a front door, wombat wants to gain their attention so chews the nice front door.

- Family wants carrots for dinner so grows carrots in garden; wombat digs them up.

- Family buys carrots from shop; wombat sits in back seat of car and eats them out of the bag.

- Family wants a nice garden bed; wombat wants to dig holes where garden bed is.

- Family wants to dry washing on the line; wombat doesn’t want things dangling onto her nose, so chews washing on line.

WHAT’S THE PLAN?

With a lazy, roly-poly character like this wombat, you aren’t going to get a complicated plan. The plan is simple: to walk to the family’s front door and make a nuisance of oneself until food is provided.

The family’s plan is to work around the mischief of the wombat, filling in holes once they’re dug, buying more carrots once the home store is depleted.

BIG STRUGGLE

Though it’s not obvious at first sight, Diary of a Wombat has a mythic structure. Rather, this is a parody of a classic story with a mythic structure. In myths, a hero goes on a very difficult journey to achieve a goal, meets lots of challenges along the way and finally gets what he wants (or not, in a tragedy). The hero then either returns home a changed person or finds a new home wherever he ends up.

The journey of the wombat is down the garden path to the front door. Sure enough, she meets obstacles along the way, but these obstacles are no more fearsome than a bush or a pair of wet pants which tickle her nose. Her ‘big big struggles’ are therefore ironic.

Okay, so until now I’ve been saying the same things, which are general rules but rules can be broken. So far I’ve told you that in a story with mythic structure the big struggles increase in intensity until one massive life-and-death big struggle. This is seen clearly in the Solla Sollew picture book by Dr. Seuss, which is why I included it in this series.

Jackie French shows us that there doesn’t need to be any big big struggle. In fact, in a parody, where nothing much happens by design, the story wouldn’t cope with one.

So what did the author do instead, to lead us gently towards a conclusion? She used a trick I’m going to call ‘accumulation’. This is exactly what it sounds like — various things from the story come together. By ‘things’, most often I mean ‘objects’. Another (really obvious) example of an ‘accumulation big struggle’ occurs in Stuck by Oliver Jeffers in which a boy gets something stuck in a tree. He keeps throwing more and more things into the tree hoping to get the other things down. The story gets more and more ridiculous as the things accumulate in the tree.

In Diary of a Wombat, the gag doesn’t rely on the accumulation plot, so it’s much more subtle. You can see it in the line, ‘Demanded oats AND carrots’. Oats and carrots have been the important twin desire lines throughout the story and they come together at the end.

WHAT DOES THE CHARACTER LEARN?

Wombat learns that if she makes a big enough nuisance of herself then the humans will give her exactly what she wants.

The reader learns, comically, that animals can train humans, not just the other way around!

HOW WILL LIFE BE DIFFERENT FROM NOW ON?

In this mythic journey the wombat finds a new home, even closer to the humans than before, burrowed under the house.

We can extrapolate that things will continue as they did before, but this time the wombat’s life is even more convenient as she doesn’t even have to walk up the garden path to get fed.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

- I’ve already mentioned Stuck by Oliver Jeffers as another example of an accumulation plot. Another example of an accumulation plot is Let’s Go For A Drive! an Elephant and Piggie book by Mo Willems. In this early reader, two characters collect all sorts of things they’ll need for a drive. These things pile up on the floor. They eventually realise they haven’t got a car so they have to play make believe instead.

- Rosie’s Walk by Pat Hutchins has other subtle similarities. The hen in Rosie’s Walk (Rosie) is unaware that a fox is trying to catch her. She walks happily through a farm. Rosie’s Walk has been heavily influential as a story in which the text says something completely different from the pictures. Jackie French’s wombat is similarly oblivious, though her life is not in danger. Like Rosie’s Walk, there is a big gap between the pictures and the text. The text is first ‘person’, from the wombat’s point of view, but only the reader knows how much of a nuisance she’s being to the humans she lives with.