A detective story is a type of mystery told through the eyes of law enforcers. Crime stories, in contrast, are often told through the eyes of the criminal. An example of a crime story is The Sopranos.

Detective stories relate the solving of a crime, usually one or more murders, by a main character who may or may not be a professional investigator. This large, popular genre has many subgenres, reflecting differences in tone, character. It always contains criminal and detective settings.

The detective duo everyone is dying to meet!

Summer in London is hot, the hottest on record, and there’s been a murder in THE TRI: the high-rise home to resident know-it-alls, Nik and Norva. Who better to solve the case? Armed with curiosity, home-turf knowledge and unlimited time – until the end of the summer holidays anyway.

The first whodunnit in a new mystery series by Sharna Jackson.

It’s October half-term and pop star, TrojKat is filming a music video in the The Tri, the high-rise block home to slueths Nik and Norva. When tragedy strikes the famous singer under mysterious circumstances, Nik and Norva set out to solve the case, with their friend George, and their impressive detective skills. The sequel to HIGH-RISE MYSTERY, another whodunnit in the phenomenal mystery series by Sharna Jackson.

Though a typical audience probably doesn’t have a firm idea of the differences, from a writer’s point of view detective, crime and thriller are three very different forms and structures. Detective stories are often marketed as mysteries, perhaps with mystery in the title.

Detective stories are super popular. The detective story, specifically the police procedural, is far more popular than crime, worldwide.

Examples of Popular Detective Stories

The copy generally reads something like this:

In The Woods by Tana French

Katy Devlin, a 12-year-old girl, is found dead at an archeological site in Dublin. Detectives Rob Ryan and Cassie Maddox are assigned to the case — the biggest case of their careers so far. But Ryan is shook by the similarities between Katy’s murder and the murder of Rob’s two best friends 20 years ago. Only Maddox is aware of Ryan’s potential involvement in that long-ago crime, but soon, Ryan becomes a suspect in this one, too.

THE FALL

A seemingly cold but very passionate policewoman goes head to head with a seemingly passionate father who is in fact a cold serialist in this procedural out of Belfast. The only thing they share is their common complexity.

The Fall is an example of a crime/detective blend, because the criminal and the detectives’ stories play out simultaneously.

If you follow the Midsomer Murders bot on Twitter, you’ll realise how the structure goes. Though Midsomer Murders is not exactly a parody, it’s considered as such by fans of gritty detective stories:

[murder victim] is found [description of dead body]. Suspicion falls on [local character or group], [motivation].

A banjo-playing philosopher is found lacerated with a prehistoric animal skull. Suspicion falls on Lower Pampling’s witch, angry that badger culling might threaten the return of the Microsoft Office paperclip.

A local pigeon enthusiast is found very well preserved after a stiff drink of embalming fluid. Suspicion falls on Bishopwood’s shuttlecock appreciation society, angry that multiculturalism might threaten more first world problems.

A celebrity atheist is found crushed under the world’s biggest scone. Suspicion falls on Midsomer Worthy’s famous magician, Gideon Latimer, angry that a police-car-fender-eating goat might threaten to turn England into a nation of coffee drinkers.

Raison d’être of Detective Stories

Detective stories are about searching for the truth. A detective story such as Broadchurch is about what lies beneath the surface of an snail under the leaf setting, and how crime can bring new revelations and meaning to long-term relationships. Our main characters don’t just ‘solve the crime’, but learn all sorts of other things, about themselves and about other people, along the way.

Political Problems With The Detective Story

Audiences love detective stories so much that journalism uses fictional tropes when reporting on real life crimes:

We will never have a real conversation about victims’ rights or decarceration or prison reform or sexual assault and harassment until we stop framing everything as a detective story, until we stop being so obsessed with these murder stories, and until we see that having everything resolved in the end, as satisfying as it is, is not the truth. That’s a narrative that [lets] us overlook all kinds of injustice.

Alice Bolin

A Brief History Of The Detective Story

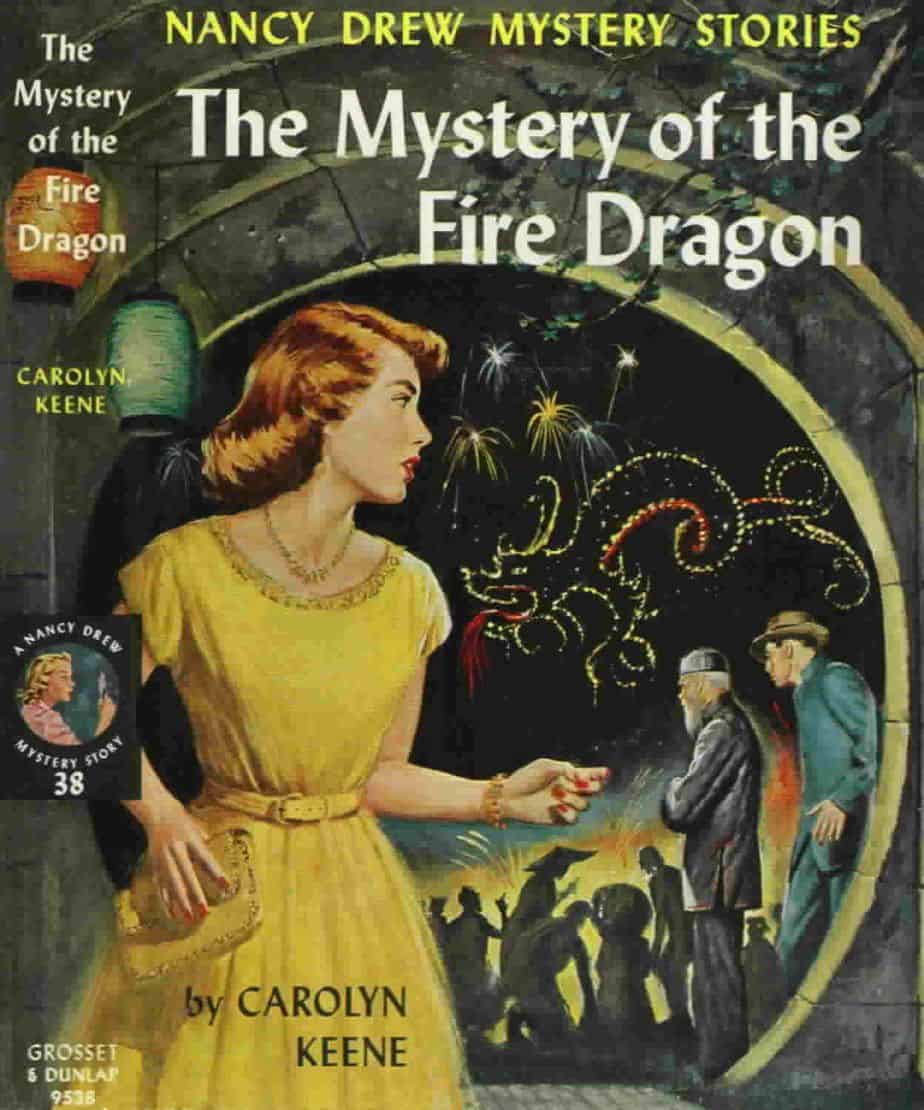

Some say Oedipus is the world’s first great detective story. Some say the first real detective story is “Murders In The Rue Morgue” by Edgar Allan Poe.

On television, Prime Suspect paved the way for other TV dramas like it:

Detective chief inspector Jane Tennison was the gateway drug. As played by the actress Helen Mirren on the British series “Prime Suspect,” she triggered my now-entrenched addiction to international crime dramas. Tennison — a relentlessly driven, hard-living, sexually indiscriminate female detective (as written by Lynda La Plante) — was exceptional and revolutionary; when the show debuted here in 1992, she had no equivalents on American TV. And Mirren was abetted by an equally riveting costar: the city of London as I’d never seen it — grubby and bristling with colorful miscreants.

NYT

We are now in the age of the ‘stage magician’ as detective:

A new way to do a cop show where most episodes see the characters solve a new case — often dubbed a “crime procedural” — is the holy grail of TV development. At this point, there’ve been so many slight variations on the detective template that something like “a stage magician helps the police solve crimes” is an actual show coming to your TV sometime next year.

Vox Culture

Lately, police procedurals are to detective stories as psychological horrors are to horror:

But now we may be heading into more of a police procedural/psychological horror blend, beginning with Mindhunter as an example.

We don’t see gruesome acts of violence — outside of the occasional crime-scene photo — and many of the criminals the cops talk to are already in prison. But there’s a creeping, chilly horror at its center, a growing sense that something is irreparably broken in the world, and nobody’s going to put it back together. […]

Mindhunter is not, by any means, a perfect show, nor does it succeed at everything it sets out to accomplish. But its intense focus on the inner workings of the human brain makes for a surprisingly fascinating watch that examines the roots of human darkness without seeming to revel in it.

Vox Culture

WRITING DETECTIVE STORIES

The detective thriller has the strongest narrative drive of all the plot types, and this is especially important for novels.

Key to any murder mystery is the complex interlocking set of relationships between its characters, but truth be told, most mysteries are quite ham-handed in their handling of it. All of the characters in the scary old house, or on the island cut off from escape, or on the creepy ship at sea, need to have some kind of relationship to one another that informs their complex motives, and that gives the author some cause for various twists, turns, and false trails (and of course, for the final reveal).

Popular Culture and Theology, A Beautiful Pattern: The Aesthetics of Virtue in Knives Out

Settings of Detective Stories

The setting is an outworking of your hero. Detective stories, crime stories, and thrillers often set up a close connection between the hero’s shortcoming—when it exists—and the “mean streets,” or world of slavery in which the hero operates.

The city is the classic detective arena. But writers can stretch that out and/or zoom in close.

In his article “In Defense of the Detective Story” Chesterton argued that the most important reason for the detective story’s cultural significance was its poetic treatment of the city.

The first essential value of the detective story,” Chesterton writes, “lies in this, that it is the earliest and only form of popular literature in which is expressed some sense of the poetry of modern life.” In other words, the detective story is a celebration of the symbolism of the city.

Characters of Detective Stories

There are certain compulsory characters in a detective story, most obviously the detective or detectives. Then there’s the victim, who may or may not be fleshed out as a 3D human being with a backstory.

Internationally, TV crime drama is becoming a feminine genre, as romance has long been a feminine genre:

More refreshing still, there is no double standard — a bonus, no doubt, of so many more female crime show creators outside of the U.S. Just like the men, women maintain their sex appeal no matter their age or shape (see the 50-something small-town cop of Britain’s “Happy Valley,” played brilliantly by Sarah Lancashire); as for hygiene — or, rather, a lack thereof — they sometimes exceed men. Weeks of plot can pass without a change of clothing. My favourite detective, Saga Noren (“The Bridge”) — she of TV’s saddest pair of leather trousers — is prone to smelling her armpits before pulling out a “fresh” T-shirt from her desk drawer. In five seasons, Laure Berthaud, the police detective on “Spiral,” has perhaps washed her hair, perhaps not. And then there’s the junk-food-scarfing detective sergeant Jackie Stevenson of “River” (Britain); her disinterest in cleanliness is staggering — though, to be fair, she is actually dead.

NYT

Whether detective stories are typically feminist (as well as feminine), however, I’m not so sure, especially as a disproportionate number of dead victims are pretty young women.

Unlike in genres such as romance, audiences don’t seem to want glamour in our detective stories. We want gritty realism:

Occasionally, American actors will cameo on these shows to jarring effect. Who are these artificially enhanced freaks with teeth like gleaming Chiclets? Any semblance of reality quickly deflates. In fact, international crime dramas have ruined our slicker network options for me. Not only do they provide off-the-beaten-track sightseeing opportunities (minus the ever-worsening indignities of flying), but viewers are treated to the attainable beauty of people who don’t look like, well, actors. Why vape when you can still smoke?

Karen Woodward

See also: Five Crime Novels Where Women are the True Detectives from The Millions

The cop with the inner demons is very popular in a detective story. Here are 5 examples of cops with big ghosts, from SBS.

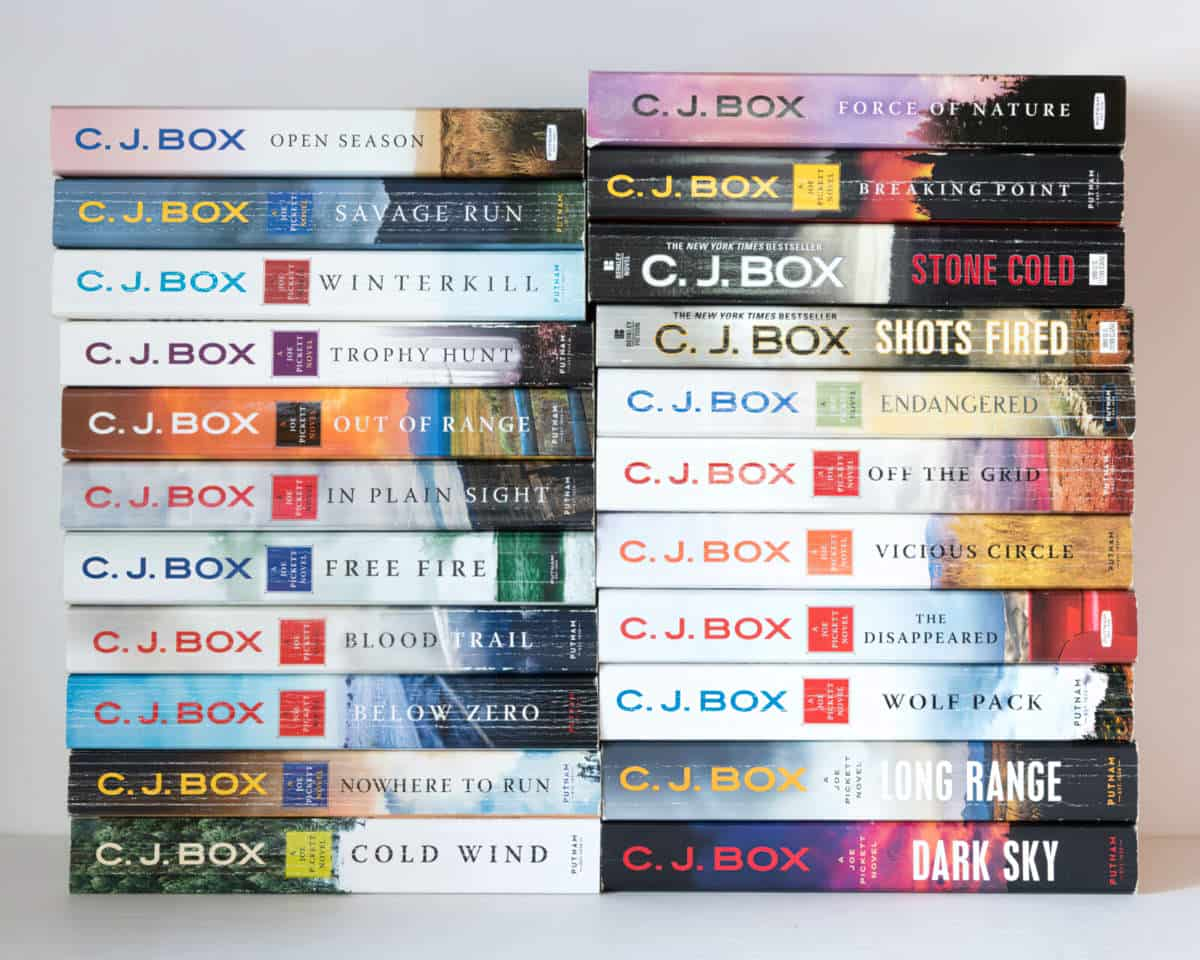

CASE STUDY: JOE PICKETT (ORDINARY GUY GAME WARDEN DETECTIVE) BY C.J. BOX

Popular Wyoming crime writer C.J. Box has said that he wondered what job to give Joe Pickett. County sheriff sprang to mind, but Box himself knows some sheriffs and doesn’t particularly like them, so he didn’t want to spend that much time with a sheriff character. He settled on game warden after shadowing a local game warden on the job, and understanding how much time game wardens spend alone. Their main job is to enforce hunting and fishing regulations. Game wardens must handle situations alone and get into uniquely difficult situations. They are part of state bureaucracy, and can’t rely on law enforcement for back up.

It really helps when your detective is a ‘lone wolf’ type person because readers ideally empathise with one person first and foremost.

Their families are part of the job. Different family members bring different perspectives and offer different reveals. C.J. Box immediately saw the potential of game warden as fictional detective.

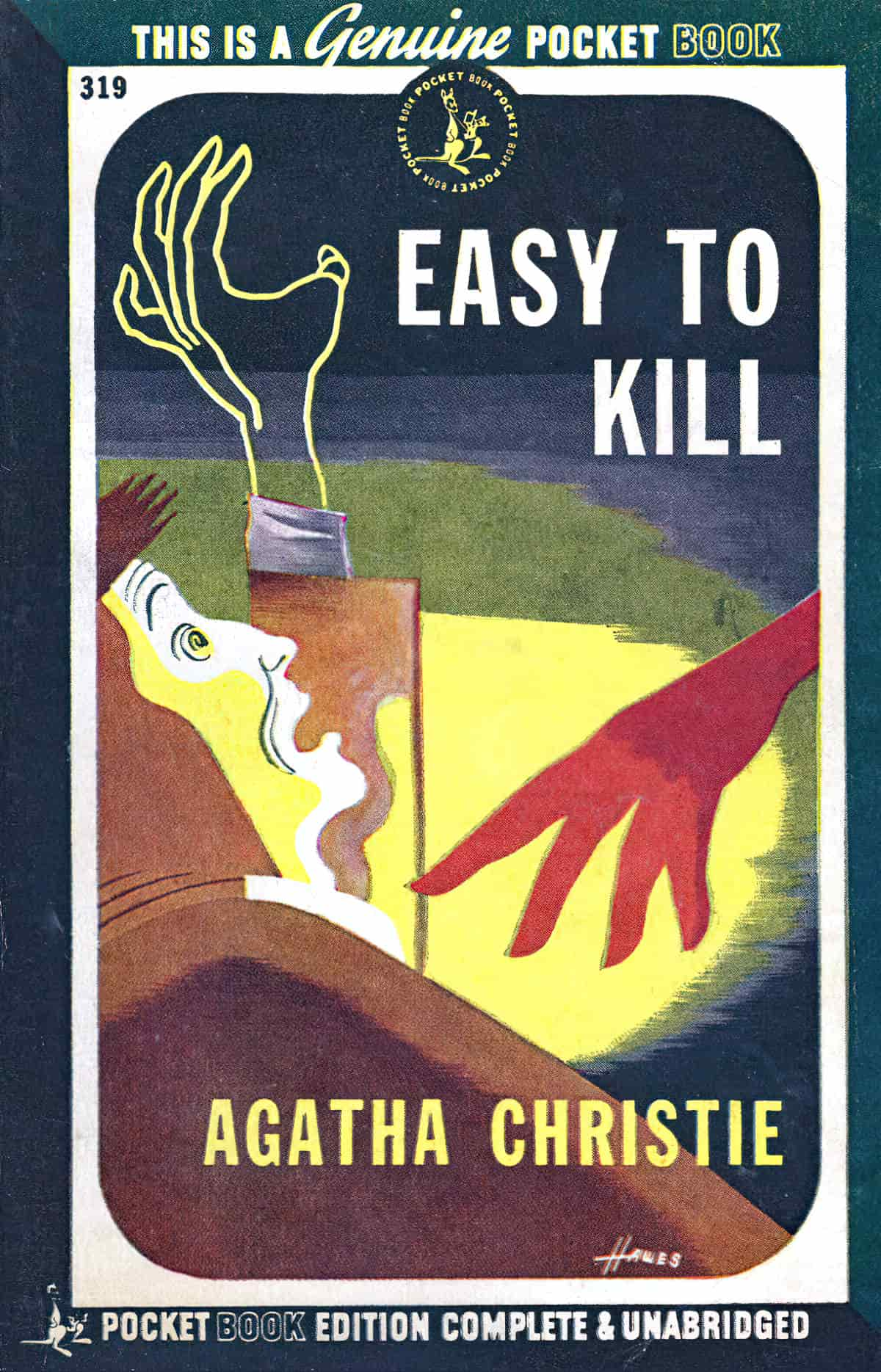

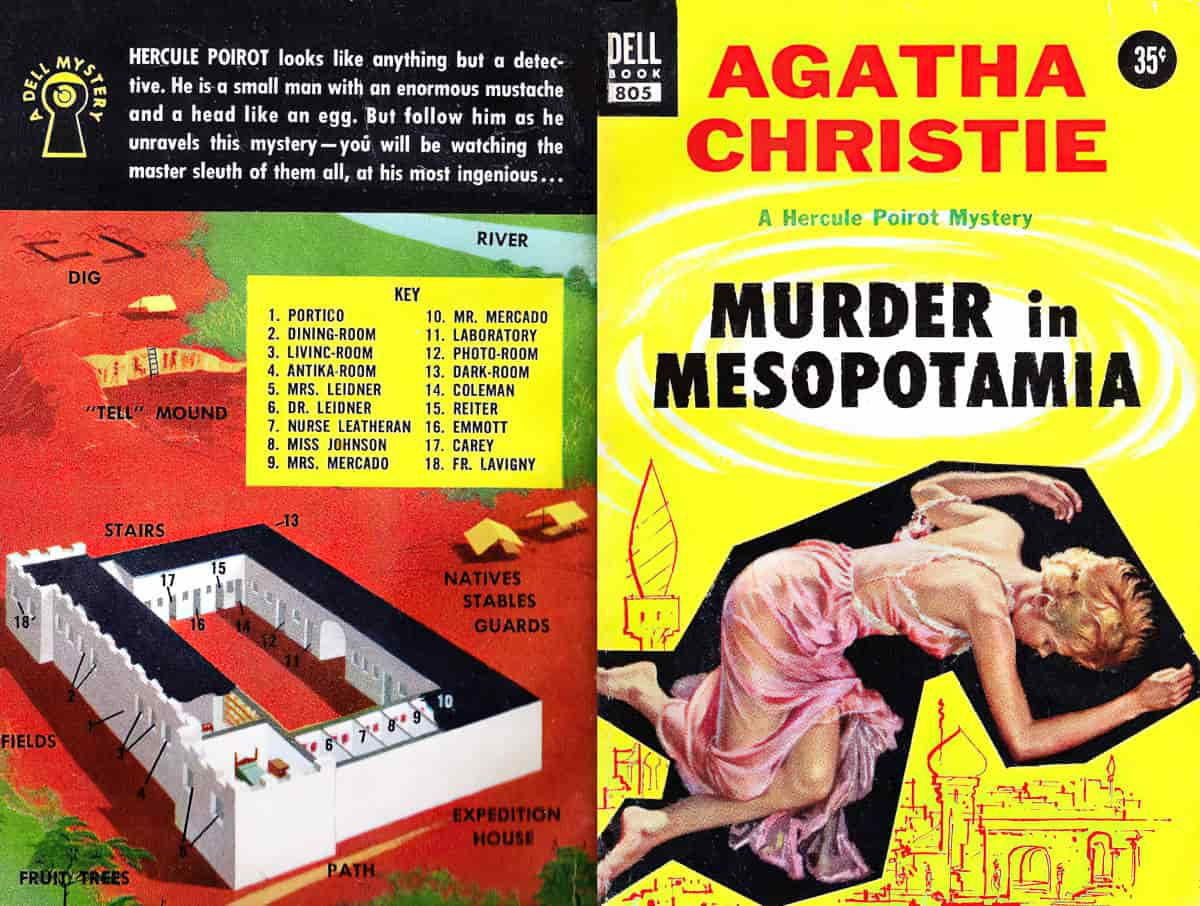

The Joe Pickett series is shelved in the mystery section of bookstores because this is where people buy books. But they’re not traditional whodunnits, so is asked often what genre these are. Box himself thought that mysteries had to be whodunnits, with planted clues (plants) and people smoking pipes. While writing the first Joe Pickett book, Box believed he was writing a contemporary novel about a contemporary issue. But the mystery genre is huge, and these days includes a wide variety of crime, suspense and thriller plots. C.J. Box goes out of his way to vary the structure in each book, dropping the reveals at different points. He also likes to write parallel with threads coming together at the end. In some of the Joe Pickett novels, the bad guy is known at the beginning.

Sometimes Box even writes from the bad guy’s point of view. In this case, the story is not a whodunnit. Reader enjoyment comes instead from watching Joe Pickett screw up and go in the wrong direction. This is fun because it involves the reader, though C.J. Box has sometimes been accused of making Joe Pickett too dim. In other books, Box keeps the criminal a complete mystery until the end so readers are following Joe Pickett on his shoulder. In Trophy Hunt, Box does plant clues like a traditional Agatha Christie mystery. In that case, the reader will probably think, ‘Yeah, I probably should have been able to figure that one out.’ But most of the Joe Pickett books are procedurals.

Box attributes the popularity of Joe Pickett his characterisation as an average, normal guy, similar to many of his readers. He’s not the guy “all the guys want to be like and all the girls want to be with”. (Excuse the allo-heteronormative quote.) He’s a family man, has a lot of self-doubt, he’s a bad shot. He’s not well-paid. His job doesn’t afford him upward mobility. He worries about money and being gone from his family. He has no deep, dark past.

Joe Pickett is not who springs to mind when we think ‘detective novel detective’. His one unusual characteristic is his dogged determination to get to the bottom of crimes.

The crime is murder. Crime novels don’t need murder, but murder automatically sets the stakes (meaning danger and suspense) much higher. Some readers avoid murder crimes, and for them the subcategory of cosy mystery satisfies that desire. Murder also appeals to the reader’s sense of justice. Readers want to see a murderer caught.

The Elements And Structure Of A Detective Story

This kind of story is at the opposite end of a spectrum of a drama like, say, Mad Men, in which every single episode has a completely different story structure. In a police procedural, every single episode has exactly the same structure.

Reveals normally happen in reverse chronological order.

Like several other genres (romance and action) there is usually a chase:

The chase is one of the basic building blocks of drama, but it does not necessarily have to involve physical movement. Detective films involve the pursuit of the killer; in conventional love stories the boy pursues the girl. […] The Terminator, Alien, The Matrix and many other recent films revolve around one long chase. One reason they work so well with audiences is that, rather than alternating between action and character development, the two proceed simultaneously.

Howard Suber

The hero’s Desire is always to solve the crime.

One police procedural that manages to be original by breaking out of the ‘single structure’ constraint is The Killing. Another is The Bridge.

7-beat Plot Structure Of A Detective Story

This is just a slight honing of universal story structure:

- Problem – someone brings a mystery to the detective

- Desire – the detective wants to solve the mystery

- The Opponent – is hidden in a detective story

- The Plan – investigation and surveillance, looking for clues

- The Battle – the detective confronts the suspect, or sets a trap

- Knowledge – the truth is revealed

- New Level – the detective solves the crime or fails to solve it

The Dual Plans of a Detective Story

In a mystery story, there has usually been a crime and there is a usually hidden Opponent. These steps apply to the Opponent, too. If you are writing a detective story or mystery, you must think of their plan as carefully as you think about your detective’s plan.

When writing Detective genre, figure out the criminal’s plan first. It seems obvious but is easily forgotten. This is how you make the story seem like magic.

The Criminal’s Plan

- Criminal has a problem

- Criminal wants something

- Criminal’s opponent is usually the law or an authority figure

- Criminal’s plan usually involves breaking the law

- Criminal commits the crime

- They usually do not learn anything

- They are happy if they succeed but…

…something usually goes wrong. Then the steps are:

- New, extra problem – someone is onto them!

- Desire – they have to keep their identity and/or crime hidden. In storytelling terms, the writer is making use of masks now.

- Opponent – the detective and/or the vigilante person who suspects them

- Plan – they often try to eliminate those who suspect them

- Battle – they confront the detective

- Knowledge – they usually learn they haven’t got away with it

- New Level – usually a lower level than before, as those who break the law should be punished, according to a typical audience, which is conservative.

So you, the author, have to come up with the opponent’s original plan and crime and also work out the detective’s plan to uncover the crime and the opponent.

You must think like a crim.

Part of the detective’s plan is looking for clues which point to the identity of the culprit. The detective looks for objects which are out of place or being used in a strange way. They rely on sight, touch, taste, smell and symmetry, or lack thereof.

Tips For Writing Murder Mystery Subplots

We’ll expect the hero to care about identifying the killer. The mystery can be in the background, but it can’t be something the hero just doesn’t care about until someone else solves it.

We’ll expect a satisfactory conclusion. Once you hooked us with a murder mystery, we’ll be deeply unsatisfied if you just end on “I guess we’ll never know.”

If there’s a murder mystery, the reader is going to get wrapped up in it, and other dramatic questions like “will she forgive her father?” will seem less important.

Because it will become your primary dramatic question, you’ll have to wrap the book up fairly quickly after the killer is revealed. You can have more scenes to wrap up your drama, but they will feel like epilogue scenes. 40 pages at most, I’d say.

I read a lot of books that try to cheat, including a murder mystery element but not giving it its due. If you want to do it, be aware that you’re taking on certain responsibilities to the reader.

Matt Bird

Pocket Books 391 – Craig Rice (Georgiana Ann Craig – the Dorothy Parker of detective fiction) – The Lucky Stiff 1947

Gritty but humorous, Rice’s stories uniquely combine the hardboiled detective tradition with no-holds-barred, screwball comedy. Most of her output features a memorable trio of protagonists: Jake Justus, a handsome but none too bright press agent with his heart in the right place; Helene Brand, a rich heiress and hard-drinking party animal par excellence (to become Mrs. Justus in the later novels); and John Joseph Malone, a hard-drinking, small-time lawyer (though both his cryptic conversation and sartorial habits are more reminiscent of such official or private gumshoes as Lieutenant Columbo).

Detective Stories As Children’s Literature

William Pene du Bois wrote and illustrated some picture books which were parodies of Raymond Chandler’s detective fiction. The Alligator Case (1965) and The Horse in the Camel Suit (1967) are examples of picture book crime parody.

Enid Blyton wrote a lot of detective stories (The Famous Five, Secret Seven and so on). Detective stories continue to be popular, and below the upper-MG age group, writers use tropes from the subgenre of ‘cosy mystery’, in which the stakes are low. (See Alexander McCall Smith’s The Great Cake Mystery).

Nate the Great is a cosy detective series for children which began in 1972. Nate is known for his unflinching resolve in the face of stolen goldfish, absconded cookies, and M.I.A. Pets.

A combination of drama and cozy crime is common in children’s literature. Timmy Failure by Stephan Pastis seems to have its main genre as drama, with a sub-genre of crime:

It doesn’t take much reading between the lines to discover that Timmy has real problems: his grades are poor, he’s not very popular, and his single mother is struggling to pay the bills while her new, thuggish boyfriend is making Timmy’s home life unbearable. Investigating a case of a missing Segway with his (imaginary) polar bear business partner makes for a good diversion.

So, there’s the crime genre in a nutshell.

A SHORT LIST OF MIDDLE GRADE DETECTIVE MYSTERIES

- The Peski Kids by RA Spratt

- The Jack Russell dog detective series by Darrel and Sally Odgers

- Violet and the Pearl of the Orient

- The Curious Cats Spy Club series by Linda Joy Singleton

- A to Z Mysteries

- Calendar Mysteries

- Friday Barnes series

- Kensy and Max series by Jacqueline Harvey

- Billie B Brown mysteries (a higher reading level than the Billie B Brown chapter books)

- Truly Tan by Jen Storer

- Mysterious Benedict Society

- Encyclopedia Brown by Donald J. Sobel

In the corrupt metropolis of Peligan City, Lil Potkin, a determined young reporter, is on the lookout for a scoop. One rainy night she meets Nedly, the ghost of a boy that no one else can see. Nedly has been looking for someone to believe in him ever since the investigation into his disappearance went cold. When they discover that his death is connected to a series of mysterious murders, Lil and Nedly set out to expose those responsible, with the help of a down-on-his luck private investigator, who might hold a clue to Lil’s hidden past.

Atmospheric, spooky, warm at heart, POTKIN AND STUBBS is the first in a hardboiled detective trilogy for readers aged 9+.

Melissa is a nobody. Wilf is a slacker. Bondi is a show-off. At least that’s what their middle school teachers think. To everyone’s surprise, they are the three students chosen to compete for a ten thousand-dollar scholarship, solving clues that lead them to various locations around Chicago. At first the three contestants work independently, but it doesn’t take long before each begins to wonder whether the competition is a sham. It’s only by secretly joining forces and using their unique talents that the trio is able to uncover the truth behind the Ambrose Deception–a truth that involves a lot more than just a scholarship.

With a narrative style as varied and intriguing as the mystery itself, this adventure involving clever clues, plenty of perks, and abhorrent adults is pure wish fulfillment.

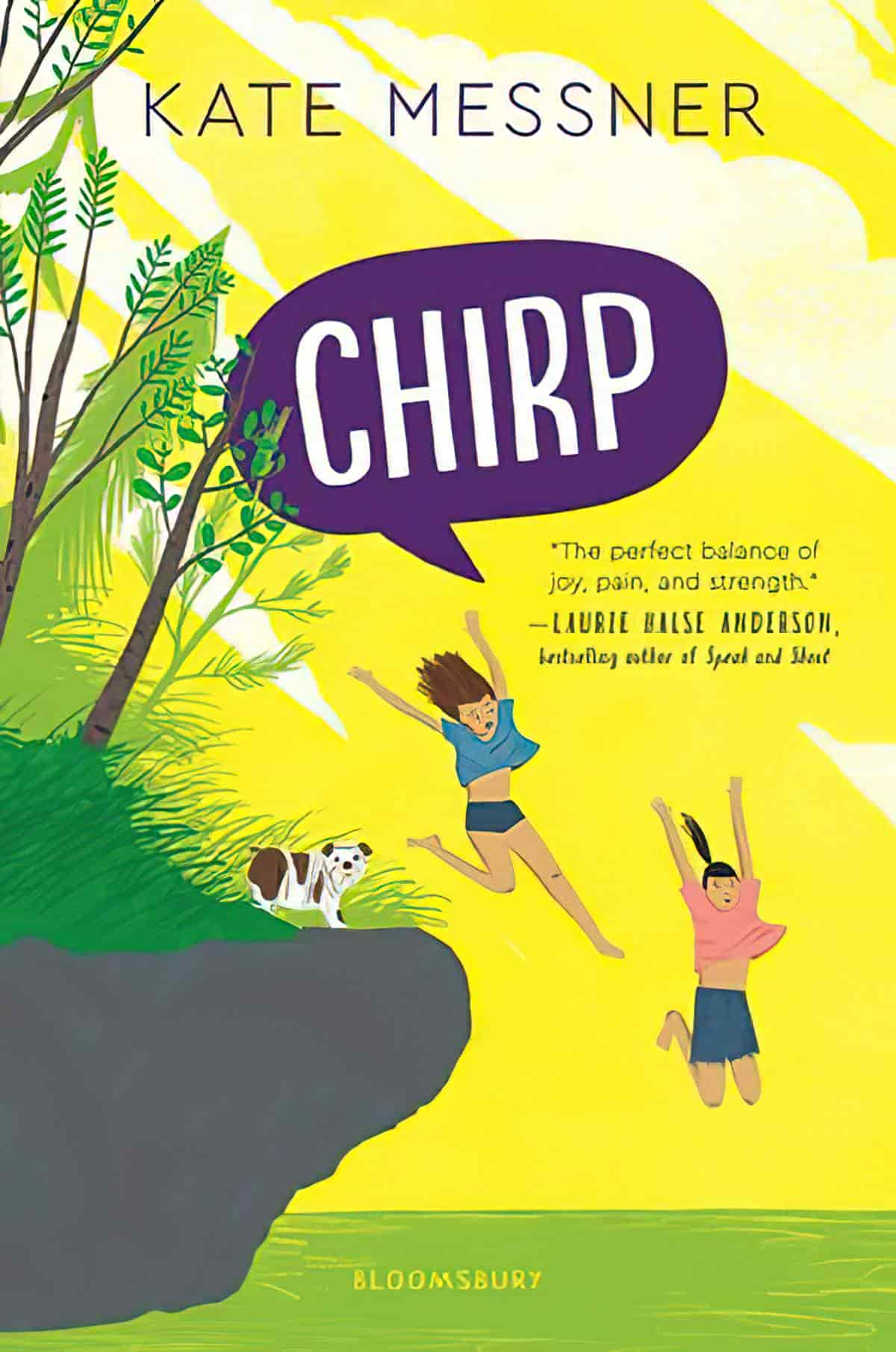

When Mia moves to Vermont the summer after seventh grade, she’s recovering from the broken arm she got falling off a balance beam. And packed away in the moving boxes under her clothes and gymnastics trophies is a secret she’d rather forget.

Mia’s change in scenery brings day camp, new friends, and time with her beloved grandmother. But Gram is convinced someone is trying to destroy her cricket farm. Is it sabotage or is Gram’s thinking impaired from the stroke she suffered months ago? Mia and her friends set out to investigate, but can they uncover the truth in time to save Gram’s farm? And will that discovery empower Mia to confront the secret she’s been hiding–and find the courage she never knew she had?

In a compelling story rich with friendship, science, and summer fun, a girl finds her voice while navigating the joys and challenges of growing up.

FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Ronald Knox’s Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction. To what extent do these commandments still apply to contemporary work?