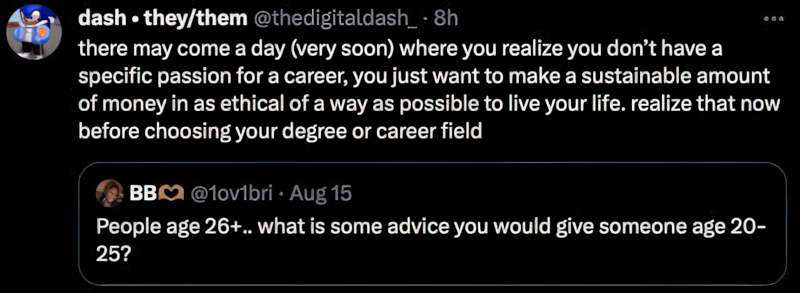

Kurt Vonnegut famously advised writers: Characters must want something, even if it’s just a glass of water.

Desire in storytelling describes what the character thinks they want. What we want is influenced by society and acculturation, so a character’s desires will be affected by their past and present setting.

There is no interpersonal situation that can’t be improved by knowing more about your desires, goals, and structure. ‘Know thyself!’

Don’t confuse ‘doing a thing because I like it’ with ‘doing a thing because I want to be seen as the sort of person who does such things’

Less Wrong

The word ‘desire’ is often used in the context of sexual desire, which connects to hunger (for food).

There are three sorts of appetites, described below by (unexpected) gastronome, Alexandre Dumas, in his Dictionary of Cuisine:

- Appetite that comes from hunger. It makes no fuss over the food that satisfies it. If it is great enough, a piece of raw meat will appease it as easily as a roasted pheasant or woodcock.

- Appetite aroused, hunger or no hunger, by a succulent dish appearing at the right moment, illustrating the proverb that hunger comes with eating.

- The third type of appetite is that roused at the end of a meal when, after normal hunger has been satisfied by the main courses, and the guest is truly ready to rise without regret, a delicious dish holds him to the table with a final tempting of his sensuality.

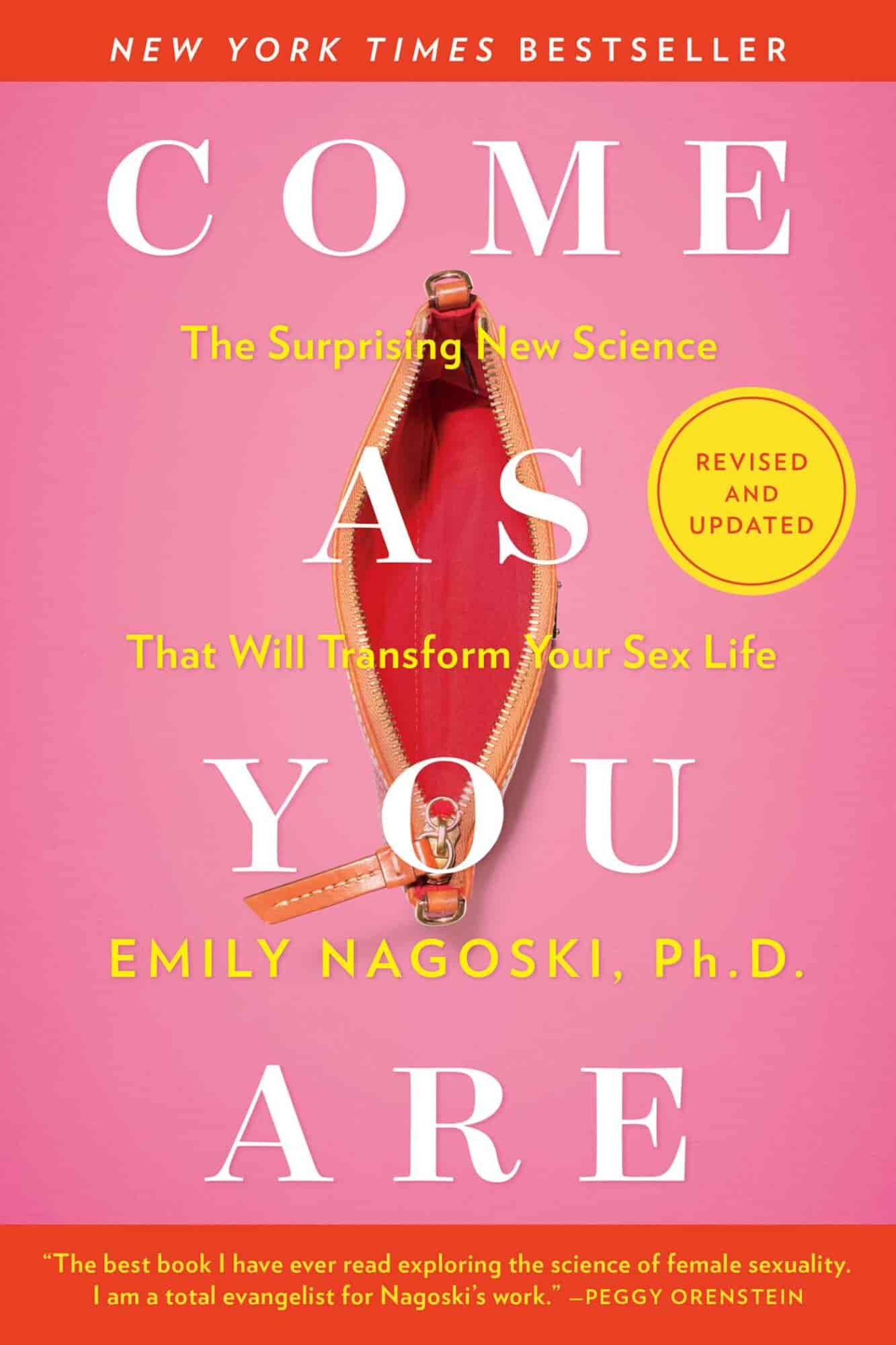

Decades later, in her book Come As You Are, Emily Nagoski talks about the difference between ‘responsive’ and ‘spontaneous’ desire. This difference between ‘responsive’ and ‘spontaneous’ is a useful concept for storytellers, because very often at the beginning of a narrative, characters don’t seem to want anything in particular.

Researchers have spent the last decade trying to develop a “pink pill” for women to function like Viagra does for men. So where is it? Well, for reasons this book makes crystal clear, that pill will never exist—but as a result of the research that’s gone into it, scientists in the last few years have learned more about how women’s sexuality works than we ever thought possible, and Come as You Are explains it all.

Every woman has her own unique sexuality, like a fingerprint, and that women vary more than men in our anatomy, our sexual response mechanisms, and the way our bodies respond to the sexual world. So we never need to judge ourselves based on others’ experiences. Because women vary, and that’s normal.

Second lesson: sex happens in a context. And all the complications of everyday life influence the context surrounding a woman’s arousal, desire, and orgasm.

Movies are still mostly showing us spontaneous sexual desire, though complex contemporary narrative seems to have moved on from the very old ‘Call To Adventure’ as described by Joseph Campbell. Interesting characters want things for a reason.

Angela Chen reminds us all that desire does not occur in a vacuum, and in fiction, too, your character wants what they want partly because they’ve been told they want it:

It is not enough to say that everyone should only do what they want. That’s a bromide that anyone can parrot and it ignores the ways that society pressures us to want certain things.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

Back to Kurt Vonnegut. According to Vonnegut, this thing characters think they want could be something run-of-the-mill. But maybe that character who wants a glass of water really needs human interaction, which is why they’ve visited the corner shop to buy a bottle of water rather than drinking it out of the kitchen tap. This advice is so fundamental, every storytelling guru will tell you a version of the same thing.

Some authors don’t bother with such low stakes as a glass of water. Before Caroline Leavitt starts any novel, she asks herself the following questions about each of her characters:

What does she want at the beginning of the novel and why? And what’s at stake if she doesn’t get it? “There has to be something at stake. It has to be something really major. I mean, if she just wants a glass of water, that’s not really interesting.”

Writer Mag

Note that ‘stakes’ is a concept closely related to ‘desire’. John Yorke prefers the term ‘active goal’ rather than ‘desire’:

All archetypal stories are defined by this one essential tenet: the central character has an active goal. They desire something. If characters don’t then it’s almost impossible to care for them, and care we must. They are our avatars and thus our entry point: they are the ones we most want to win or to find redemption — or indeed be punished if they’ve transgressed, for subconsciously we can be deeply masochistic in our desires. Effectively they’re us. […] If a character doesn’t want something, they’re passive. And if they’re passive, they’re effectively dead. Without a desire to animate the protagonist, the writer has no hope of bringing the character alive, no hope of telling a story and the work will almost always be boring.

John Yorke, Into The Woods

Velleity: A wish or inclination not strong enough to lead to action.

Without desire, no story, so the story gurus tell us. This is so basic — at first glance what more could be to it?

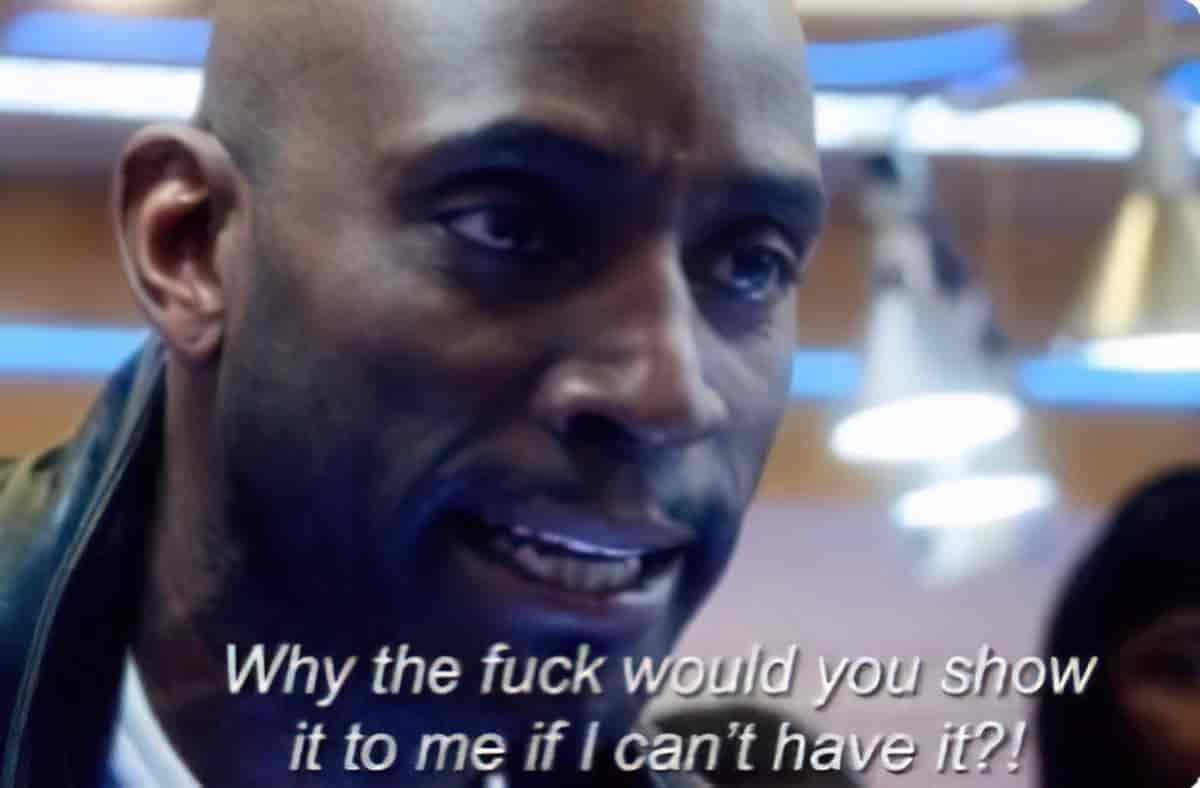

When a character has a strong desire they go on an important quest and undergo significant character change as a result. Achieving their goal must be hard. It can’t come easily or you don’t have a fully-fleshed story. So everyone knows this — everyone gets the joke in that comic — but when you sit down to write your actual story you may find yourself wrestling with the following:

- Your character doesn’t want anything of interest to an audience. In fact, they just want to stay in their room all summer playing computer games under a blanket.

- Your character did want something, but now they’ve got it and your story doesn’t feel long enough, or quite finished.

- You might know what your character wants, but what if they don’t? What if you need your character to be lacking in self-awareness?

Low ambition offends Americans even more than low achievement.

Scott Sandage, Born Losers: A History of Failure in America

CHARACTER SHORTCOMING AND ITS LINK TO DESIRE

You learn a lot about people when they don’t get what they want.

Your character’s shortcoming is linked to their desire. (Click through on that link for a whole lot more.) A character’s desire is always contingent upon what has happened before.

Maybe desire is nothing but memory,

Tracy K. Smith

And we dream only what has already been.

ESTABLISHMENT OF DESIRE EQUALS BEGINNING OF STORY

DESIRE BECOMES CLEAR AT THE INCITING INCIDENT

If you think of story structure in terms of ‘inciting incidents‘ (of questionable value), the main character’s desire becomes clear to the main character and to the audience after the inciting incident. That’s what the inciting incident is for. A specific type of inciting incident is Hitchcock’s ‘McGuffin’. This is an inciting incident which the audience has completely forgotten about by story’s end. The best inciting incidents subvert readers’ expectations. Inciting incidents aren’t always so easy to pick as an ‘explosion which rocks the main character’s world’. It can be much more subtle.

- The protagonist will be alerted to a world outside their own.

- They will make a decision on how to react to this and pursue a course of action that will precipitate a crisis.

- This will force them to make a decision propelling them into a whole new universe.

FULFILMENT OF DESIRE EQUALS END OF STORY

Joss [Whedon] makes his living denying people what they want.

James Marsters

Whedon seems to live by advice as explained by Karl Iglesias:

A scene with a chase-and-capture dynamic (the character achieves their scene objective) or a chase-and-escape (they don’t get what they want). A balanced plot line will often include scenes that alternate between the two. Once the writer establishes the central question of whether the protagonist will accomplish their goal, the scenes that answer, “Yes they will!” in a small scene victory should alternate with “No they won’t” in a defeat, back and forth. This alternates the potent visceral emotions of hope and worry. Because a scene is like a mini-story, its beats can also alternate between satisfaction whenever the central character gets a step closer to getting what he wants, and frustration whenever there’s a setback, creating a dance between hope and worry within one scene, and thus keeping the reader hooked.

Karl Iglesias, Writing For Emotional Impact

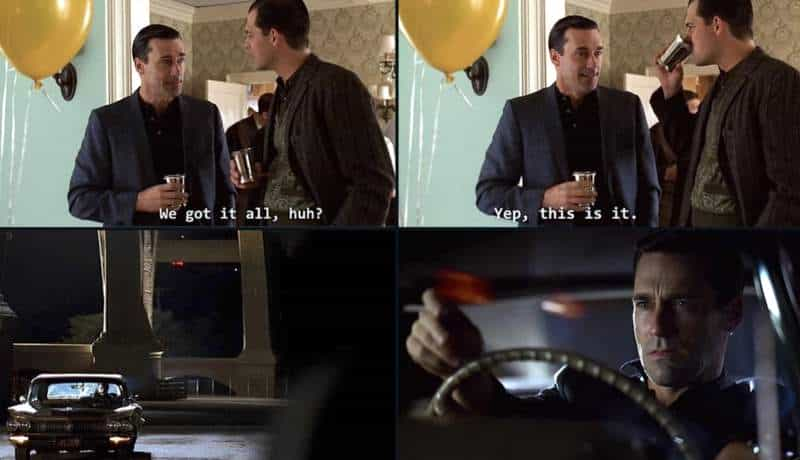

Likewise, when your character has got what they want, your story is over. (Or maybe your main character does not get what they want, in which case you’ve written a tragedy.) If they get what they want ‘halfway through’ your novel, avoid trying to fix that problem by giving them a new desire. New desire means a new story.

“There are two tragedies in life. One is to lose your heart’s desire. The other is to gain it.”

George Bernard Shaw (Both work irl; only the first applies if it’s fiction.)

However! Desire mutates. Desire strengthens. In fact, in many, many stories you’ll see a passive underdog main character drawn unwillingly into adventure but at the halfway point (and yes, it’s usually exactly the midpoint in a film) they’ll ‘double down’. Now they really, really want that thing they were meh about at the beginning. Desire does not change over the course of a single story. Your main character has one main desire, they go to the ends of the earth to get it (or not) and then the story is over. Contrast this with ‘character plans‘. Plans change all the time. Initial plans fail and characters must invent increasingly ingenious ways to overcome opponents.

In uncertainty I am certain that underneath their topmost layers of frailty men want to be good and want to be loved. Indeed, most of their vices are attempted shortcuts to love…We have only one story. All novels, all poetry, are built on the neverending contest in ourselves of good and evil. And it occurs to me that evil must constantly respawn, while good, while virtue is immortal. Vice has always a new fresh young face, while virtue is venerable as nothing else in the world is.

John Steinbeck, East of Eden

Some critics think in terms of three layers. Some storytellers think of desire as two-tiered: The surface desire (they want to be included in a group of friends, they want to get their hands on a fairy cup) and deep desire (they want friendship, they crave economic stability and prestige).

Others think in terms of three layers of desire. The Dostoevskian character has at least three layers, writes James Wood in How Fiction Works:

- TOP LAYER: The announced motive.

- SECOND LAYER: Unconscious motivation. Those strange inversions wherein love turns into hate and guilt expresses itself as poisonous, sickly love.

- BOTTOM LAYER: Can only be understood religiously. These characters act like this because they want to be known; even if they are unaware of it, they want to reveal their baseness. They want to confess. They want to reveal the dark shamefulness of their souls. They act scandalously and appallingly without quite knowing why.

(This all explains why Freud and Nietzche were attracted to Dostoevsky’s work.)

It is easier to suppress the first desire than to satisfy all that follow it.

Benjamin Franklin

RATIONAL AND IRRATIONAL DESIRES

One function of dreams in literature is to convey to the audience what a character really desires, compared to what they think they desire. Erich Fromm marks this distinction as ‘rational’ vs ‘irrational’ wishes in a chapter about dream interpretation:

We often wish things that are rooted in our shortcoming and compensate for it; we dream of ourselves as famous, all powerful loved by everybody, etc. But sometimes we dream of wishes which are the anticipation of our most valuable goals. We can see ourselves as dancing or flying; we see the city of light; we experience the happy presence of friends. Even if we are not yet capable in our waking life to experience the joy of the dream, the dream experience shows that we are at least capable of wishing it and seeing it fulfilled in a dream fantasy. Fantasies and dreams are the beginning of many deeds, and nothing would be worse than to discourage or depreciate them.

Erich Fromm, The Forgotten Language

This is also how storytellers make use of symbols and motifs — the storycrafting equivalent of dreams.

FAIRYTALE AND ROMANTIC DESIRES

Why does Rumpelstiltskin want the young woman’s first born? Why does the Erl-King want the boy, for that matter? We’re never told. It’s not supposed to matter.

In fairy tales influenced by the Romance era, character desire doesn’t seem to be as vital to story as mood and symbolism. Romantic poets weren’t about being the active participant, having a desire then going after it. Instead they were more about being tortured souls, the original Goths, haunted by poetry, at the whims of strong forces, often supernatural, outside their control and understanding.

The three most famous poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge are “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, “Kubla Khan” and “Christabel”. Each one of these poems features a main character whipped away from themselves by some violent and supernatural force. Likewise, Keats wrote odes in which the speaker takes leave of himself by way of contemplation.

These Romantic narratives are not about the desires of the ‘main characters’ (or rather, victim muses) but rather about the desires of the gods. The desires of gods are left off the page. Mere morals can never hope to understand the desire of the gods, and that is the very point. The mere mortals in these poems also remain mysterious to us because we’re not told anything about their wants and needs, either. This makes them different from the regular reader. Obfuscation of desire is a feature of Romantic stories and is deliberate.

The modern audience wants something different from fictional characters. We want to walk in their shoes, to experience another world as they experience it, to undergo a character arc as they do. What applied to Romance poems does not apply to modern stories. This is partly to do with how we are not a religious population in the same way. We don’t explain the world by reassuring ourselves with, “Oh, well, we can’t possibly know what the gods are thinking.” (Though we do still recognise the phrase, “God works in mysterious ways!”)

When modern storytellers take hold of those old narratives and fairytales influenced by Romantic sensibilities, the desire is left wide open and therefore open to fresh interpretation. This makes for a wide variety of re-visionings. What does the Erl-King want with the boy? Well, he could want sex (in a darkly erotic tale). Or he might want him as another kind of servant, or he may have blood lust and desire to kill him. The possibilities are endless.

DESIRE IN FEMININE GOTHIC FICTION

Published in 1818, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley was hugely influential, partly for affording The Other human emotions, turning him into a sympathetic character. This started a new form of Gothic literature which some people call the feminine Gothic.

Desire has always been a problematic issue for women (forbidden, suppressed, problematised, medicalised) so it’s natural that woman creators have messed with it through their art.

Desire plays a big part in feminine Gothic fiction. In Gothic texts there is generally some kind of violent separation at the beginning. In fact, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has gone so far as to say that separation is one of the most characteristic gothic conventions.

Examples

- Separation from mother through death (Udolpho, though dead mothers are rife throughout the history of storytelling)

- Separation from daughter through imprisonment (Maria)

- Separation from creator through abandonment (Frankenstein)

- Separation from family through exclusion (Jane Eyre)

And so it follows that the character desires reconnection. Note that the desire for reconnection applies to a vast number of modern narratives.

UNORIGINAL DESIRES

Michael Hauge urges writers not to worry about unoriginal desires. The desire is probably not where the originality of your story will come from, since we all basically want the same things (see Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, misappropriated from Native Americans):

Don’t worry about your hero’s desire being trite and familiar. Just about all visible goals in any genre have been done many, many times. Usually they are some version of either winning a battle or competition (HUNGER GAMES), winning another character’s love (THE PRINCESS BRIDE), escaping a bad situation (JUMANJI: WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE), retrieving something of value (any Indiana Jones movie), or stopping something bad from happening (any MISSION IMPOSSIBLE or AVENGERS movie). As for inner motivations, they will almost all be to gain love, acceptance, power, revenge or significance.

It’s the CONFLICTS heroes face in pursuing their desires, and the ways they plan to overcome these obstacles, that will make any story original and emotionally involving. So, focus on the external obstacles your hero must conquer to achieve her goal, and the inner conflict that pits your hero’s fear and identity against the emotional courage she must show to fulfill her destiny.

Michael Hauge

LESS COMMON DESIRES

Mauerbauertraurigkeit: The inexplicable urge to push people away, even close friends who you really like.

Lachesism: The desire to be struck by diaster, e.g. to survive a plane crash or to lose everything in a fire.

Liberosis: The desire to care less about things.

CHARACTERS WHO DON’T WANT ANYTHING

Some characters have no ikigai.

Ikigai is the Japanese term for the state of well-being induced by devotion to enjoyable activities, which leads to a sense of fulfillment, according to Japanese psychologist Michiko Kumano.

It is said that in Japan, people who have a purpose in life live longer.

Your ikigai is what gets you up every morning and keeps you going.

Better Humans

One way of dealing with the boredom of our own needs might be to complicate them unnecessarily, so as always to have something new to desire. Human needs, Schopenhauer thought, are not in their essence complex. On the contrary, their “basis is very narrow: it consists of health, food, protection from heat and cold, and sexual gratification; or the lack of these things.” Yet on this narrow strip we build the extraordinary edifice of pleasure and pain, of hope and disappointment!

Zadie Smith, “Windows on the Will”

These people exist in real life, right? So they also need to exist in fiction.

Indeed they do. A lot of coming-of-age stories are about teenagers mooching around, for instance. A good example is Greg from Me, Earl and the Dying Girl. These characters are defined by what they don’t want rather than what they do want.

Contrasting with…

(Megan McDonald’s Judy Moody title is comically hyperbolic — preadolescent Judy Moody is interested in finding her place in her own community.)

Characters who seem to want nothing still want something. They want homeostasis. Or, they may want someone else to do the thing that they want:

We often think of motivations as taking the form of wanting to bring about some state of affairs. They may also, however, take the form of wishing some state of affairs to obtain. This distinction between wants and wishes is important.

Explaining Social Behaviour by Jon Elster

Don’t tell me where your priorities are. Show me where you spend your money and I’ll tell you what they are.

James W. Frick

ACTIVELY PASSIVE CHARACTERS

The fact remains, fictional characters who want stuff but don’t actually do anything about it don’t make for compelling story.

What if your character is not a cop or a surgeon or a hero? What if they want to sit on the couch? If you have a passive main character (and by ‘main character‘ I mean simply ‘the character we see the most’), one workaround is to make them actively passive. That’s key.

Also key: Things are happening around them. Other characters must have strong desires. Even to maintain their status quo, your main character must go out of their way to maintain it.

THE CONCEPT OF THE ‘PHERE’

Phere is a Jungian concept, pronounced ‘fear’. In relation to story structure, Shawn Coyne has talked about it. He describes it like this:

it’s the unit of energy that turns a unit of story. … it’s a unit of energy that comes into a story that creates fear in the character. … The phere is the thing that induces the shift in valence from satisfied to unsatisfied.

Storygrid

In real life people don’t tend to put their lives at risk to get things they really badly want, right? Most people just hang around sort of satisfied with the status quo. If your main character doesn’t have a ‘desire’, per se, better perhaps to talk about ‘whatever gets them fired up’. Here’s another thing Shawn Coyne has to say about pheres:

If it’s the beginning hook, you’re probably going to start with a big phere and then you’re going to taper off and then move up and it’s like the movement and the expansion of the energy applied to the system will create a cathartic experience at the end.

In almost all stories, desire grows stronger and stronger over the course of a story. We might therefore think of a phere as a ‘Macguffin Desire’. It’ll do until the til-death-do-us-part desire takes over and drives the main character into big struggle.

CHARACTERS WHO HAVE CONFLICTING DESIRES

This isn’t a problem in your storytelling because a story starring character with two conflicting desires is a story about… conflict! And conflict is good for storytelling. Also, people are walking contradictions. We all want conflicting things.

In his book What Makes Us Tick? Hugh Mackay talks about our conflicting desire for homeostasis and predictability which rubs up against our need for constant change. He also points out that we can want something badly, but as soon as we get it, we wonder why we craved it in the first place.

The question is: why? Is it that we know, deep within us, that if we don’t change we will wither and die, intellectually and emotionally, if not actually?

Or is it that we crave change more than we care to admit; that we love surprises and challenges because they bring us to life and force a reaction from us? Yet the very notion of upheaval is at war with our apparently sincere wish for stability and stasis. Just as the homeostatic mechanisms of the body automatically adjust for tilt or for temperature change (making us shiver to warm up or sweat to cool down), we imagine that we automatically seek that kind of emotional stability, too. Who wants to be shocked by an unwelcome turn of events? Who wants to be obliged to change their minds?

Perhaps this tension between our intellectual need for surprise and uncertainty and our emotional need for security and stability accounts for the restlessness of the human spirit documented by poets, philosophers, theologians and psychologists. It often feels as if we desire one thing and desire its opposite.

Hugh Mackay, What Makes Us Tick

Of course this bundle of conflicting desires will be reflected in fiction, and indeed makes for the most interesting kind of fiction.

FEMINISM AND GOALS

Female characters sometimes seem passive but in fact they are limited by the setting, not permitted to pursue a goal even if they have one. ‘Goals’ as necessary elements of fiction are therefore a feminist issue.

In my education as a TV writer, I heard the same advice on repeat: your protagonist must drive through a story in the relentless pursuit of a goal. This gold standard of storytelling exists for good reason. Stick to it and your story will be clear, your main character a hero, and your narrative comfortable and familiar enough for people to invest in emotionally. In other words, something must happen externally. They have to be forced into action, even if it’s in a vain attempt to keep everything exactly the same as it was before. Often in realistic fiction it’s the annoying mother or a teacher on their tail. In a fantasy/thriller there’s a much wider range of villains who can enter the story to turn a character’s life upside down. … She is limited, and the audience is made to feel this limitation. Women are not often allowed to manipulate this sacred storytelling framework in television. Men, and male-centered narratives, have dominated the small screen from the early days of three-camera sitcoms, right through to what’s now being dubbed as The Golden Age of TV. These narratives privilege a quintessentially male experience. An experience where you get to do what you want, when you want, mostly free from systems that control your movements and decisions. The ideal of the active protagonist assumes your main character is free to act. But it’s hard to venture forth when the deck is stacked against you.

Courtney Jane Walker, What Makes Alias Grace So Good

Cynthia Benis Abrams hosts a podcast called Advanced TV Herstory. The episode from March 22 2018 is about a new kind of aimless character. In TV series, female characters can be divided into categories according to what they want:

- Wants to get married

- Wants to dedicate self to family

- Working mother, often single

- Retired woman (these are few — standout example is The Golden Girls)

- Feminerd — great at her job, not so lucky in love. Wants it all. (The Mindy Project, New Girl)

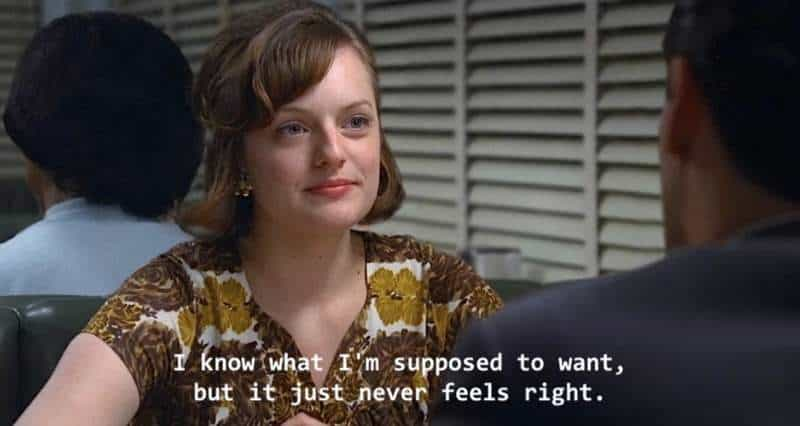

- The woman who isn’t sure what she wants out of life. This character lets life happen to her. She spends her time responding to external events.

This sixth category is especially interesting from the writing and desire line point of view. Why does this character find popularity and what gave rise to her? The answer to that can be found in the history of melodrama, which I wrote about here. Like the Romantic poems, melodrama features characters who respond to external events rather than drive them. This is why melodrama is considered a feminine form of storytelling.

However, the woman who doesn’t know what she wants is limited to the cable networks rather than seen on the big screen. The big, public networks aren’t taking risks on this kind of aimless woman, yet. This indicates she’s still pretty niche. Look at the following examples and you’ll know people who can’t stand these shows, indicating their niche-ness:

- Piper Chapman in Orange Is The New Black. (I can’t bear this character myself — she’s the weak link in the entire cast.)

- Jessa from Girls, who starts out as a party girl. She marries but it doesn’t last. She has no clear goals throughout most of the series, but she does find herself later on, lending a sense of conclusion to the series.

- Chloe from Don’t Trust the B**** in Apartment B.

There is one example from an earlier era. The Days and Nights Of Molly Dodd ran from 1987-1991 and stars a woman who is reactive rather than proactive. She is roll-over nice but isn’t the go-getter audiences had gotten used to after second wave feminism of the 1970s.

This woman is a new trope, specific (mostly) to the 2010s. This probably reflects the dominant American culture, in which millennial women can have two postgraduate degrees from an Ivy League and still find themselves under- or unemployed. Young women no longer believe that it’s possible to have it all. Their grandmothers (or mothers) were the first to have a choice between family and career or both. I come from an in-between generation where there was never any doubt that family and career can go hand-in-hand, but with rising student debt and house prices, millennial women are realising kids might be impossible, even if they want a family. The sit-com Friends is perhaps the bridge between those second wave feminist women and the Piper Chapman/New Girl trope.

Season One of Friends is a great one, for a sitcom. It’s not a great season for Friends, by a mile. The show would soon find its footing with more serialized storylines, and the cast would only get better with time. Even so, the early episodes did a great job of introducing us to the gang and making us want to hang out with them again. The plot would thicken up nicely, but at first it was simple. Twenty-somethings navigating the usual travails of young-ish adulthood, most of which can conceivably be worked out in 22-minutes: Rachel can’t do laundry, so Ross teaches her how. Joey and Chandler’s crappy kitchen table breaks, so they buy a new one—a foosball table! The girls have a moment of existential dread, realizing that youth is past and life is chaotic and they “don’t even have a pla,” let alone a plan. So, they get drunk, problem solved.

Entertainment Weekly

I haven’t looked into TV’s aimless men, but that would be interesting to compare. Brett and Jemaine from Flight of the Conchords are fairly aimless, but their backseat goal is to get gigs. They are just as easily sidetracked by getting jobs as sandwich boards or making helmet hair. I’m not sure if this counts as ‘aimless’, or if it’s more accurate to say their aims are comically trivial.

WHEN CHARACTERS DON’T KNOW WHAT THEY WANT

I want – I want – I want – was all that she could think about – but just what this real want was she did not know.

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

The female sit-com characters listed above demonstrate that a story can be successful even when they are basically aimless.

There is still much room in the world for stories about characters who think they know what they want, because everyone else seems to want it, but who then question their mimetic desire:

In theory, mimetic desire can be perfectly fine. In practice, the world is not a neutral place. … If you don’t know who you are or what you want, the world will decide for you. It will show you a couple of options and tell you those are the only ones. As so many people throughout this book have said, it takes active work to step back, to create even enough space to take a breath and admit that maybe you don’t know what you want, but what has been offered has never felt right. … It takes active work to step back, to create even enough space to take a breath and admit that maybe you don’t know what you want, but what has been offered has never felt right.

Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen

Naturally, child characters aren’t going to know what it is they want. Knowing what we want takes maturity and reflection.

“I don’t want whatever I want. Nobody does. Not really. What kind of fun would it be if I just got everything I ever wanted just like that, and it didn’t mean anything? What then?”

Neil Gaiman, Coraline, p112

Middle grade novel Coraline is of course written in the tradition of melodrama.

Part of the interest of a character is seeing them come to an understanding of what they want:

- A teenager wants to stay out all night and party past curfew but what they really (also) want (need) is to show their parents that they are grown now, and don’t need to live life by their parents’ rules. (Young adult literature)

- A toddler wants to eat ice cream instead of broccoli, but also wants/needs to show their parents they are the boss of what goes into their mouth. (Picture books)

- A future king wants to overcome his stuttering in order to give a speech but wants/needs to prove to himself, his family and the public that he is up to a leadership role. (Adult film)

The most interesting goals will be an outworking of the main character’s deep-seated desire. Greg from Me, Earl and the Dying Girl wants love and wants to be accepted, which is precisely why he has made it his mission to cheer up the dying girl.

A common combo: The character knows what they want on the surface (the treasure, new shoes, to get away from the monster), but doesn’t understand themselves well enough to know what they want at a deeper level. This is where fairy stories come in. To use the word ‘fairy’ in the broadest sense, a fairy stands for a desire which cannot be expressed. Perhaps this desire is too terrifying to confront head-on. Perhaps it simply cannot be named.

WHEN WRITERS DON’T KNOW WHAT THEIR CHARACTERS WANT

As explained above, just as we often have conflicting desires, it is very common for people to not really know what we want. In narrative, this isn’t very satisfying to a modern audience. Plenty of characters don’t know what they want. That’s why they’re sitting around waiting for life to happen to them. But in a story, at some point they must either realise what it is they desire (based on psychological need) or not, in which case this will be their downfall. We all want many things. Janis Joplin wants a Mercedes Benz, a colour TV, and a night on the town. That’s just the conscious desire, by the way. What she really wants is to be valued as much as her friends are.

CHARACTER DESIRE AND WOMEN

Most of the storytelling gurus work for screenwriters and are men. I would like to add to the discussion: Female characters, in fiction as in real life, will attract audience criticism for expressing certain desires and it’s important for writers to understand this basic gender difference sexism when creating a story. Jill Soloway (non-binary) is one of the big name California writers, and has this to say about women and desire as it relates to their experience directing in the macho world of Hollywood:

Women are shamed for having desire for anything — for food, for sex, for anything. We’re asked to only be the object for other people’s desire. There’s nothing that directing is about more than desire. It’s like, ‘I want to see this. I want to see it with this person. I want to change it. I want to change it again.’ It’s like directing is female desire over and over again, and film is the capturing of human emotions and somehow men were able to swindle us into believing that that is their specialty. All they told us our whole life is we’re too emotional to do any real jobs, yet they’ve taken the most emotional job, which is art making about human emotions and said we’re not capable of it.

Jill Soloway calls for a matriarchal revolution: There is a “state of emergency when it comes to the female voice”

Jill Soloway recently adapted I Love Dick for TV — a story which is in its entirety about the most taboo female desires.

I don’t care how you see me, I don’t care if you want me. It’s better that you don’t. It’s enough that I want you.

the main female character to an imaginary male object of desire

If characters must have desire in order to be interesting and, as Jill Soloway has noticed, women aren’t permitted desire in the dominant culture, it follows that any female characters are likely to be less interesting than male characters, relegated to supporting roles and turned into objects. There are many, many examples, but here’s one:

It’s rare to see any film, much less a PG-13 one for broad audiences, present a woman as a sex object as blatant as Lady Lisa, a fantasy who falls into a man’s arms without so much as a word

from review of Pixels in Vanity Fair. Pixels was released in 2015.

Jill Soloway’s I Love Dick is a response to this long history of storytelling. Perhaps there are some desires which are more specific to women. Jane Caro mentions Hugh McKay’s book What Makes Us Tick in this article, in which Caro expands her definition of feminism to mean, basically: The desire to be taken seriously. That’s the desire of many women, and of many female characters in particular.

DESIRE AND CHARACTER EMPATHY

In fiction there’s a surefire way to set up the villain of the piece: The villain is the one who wants money and power. Especially power.

THE ROLE OF OPPONENTS

Somebody’s got to want something, something’s got to be standing in their way of getting it. You do that and you’ll have a scene.

Aaron Sorkin

EVERY CHARACTER NEEDS THEIR OWN DESIRE

Peripheral character ego. The antidote to superman syndrome, the legitimate desire of peripheral characters to be doing something even when being ignored by the protagonists and author. Every peripheral character should behave (whether onstage or off) as if he or she is the most important actor in the story, with his or her own genuine motivations and independence. Tom Stoppard, the maestro of this conceit, built it into a whole play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. (CSFW: David Smith)

Glossary of Terms Useful When Critiquing Science Fiction

DESIRE AND WRITING SCENES

This is a tip from Karl Iglesias in Writing For Emotional Impact. In each scene, the lead character of that scene will have a desire. If sketching out a story plan, Iglesias advises phrasing that character’s desire in relation to that person’s opponents in the scene:

NOT: Spongebob goes to the Krabby Patty hoping to get a job. INSTEAD: Spongebob goes to the Krabby Patty to persuade Mr Krabs and Squidward to give him a job.

The reason for doing so? To remind yourself that every dramatic scene requires conflict of desires. (For more on Spongebob, see this post.)

GENRE AND DESIRE

Each genre has its own desire tropes.

Romance

For instance, in romance the reader knows that the main character wants to find love. Though what they really want is to find wholeness, and themselves reflected in another individual.

There are countless reasons to read romance novels and much to love about the genre. But ten months into my journey as a newbie romance reader, I’ve finally realized what I personally love so deeply and completely about romance: I always know what the character wants, and I know they’re going to get it. […] Characters in romance novels can be just as deep and nuanced as any other characters in fiction. They can want complicated or contradictory things; they can make mistakes; they can spend a hundred pages pining over the wrong person before finally realizing that it’s someone else who will make them happy. But unlike other kinds of fiction, the underlying current of desire, the thing that drives the plot, the mechanism that makes you turn pages—is never, ever a surprise.

Bookriot