How to describe woman and girl characters in fiction? There must be a handbook somewhere. (No, only the entire history of literature.) The following tropes are so common they can be found throughout stories over time, including in books for children. On the other hand, writers of children’s literature are also the most likely to invert established tropes. We see successful subversions from children’s authors.

Every single female detective/cop, as written by a man: Hi I’m Toughy McLady I am the only (or youngest, or both) woman in my department. I push myself too hard. I have a secret hurt in my past that I refer to obliquely but never outright explain until the 5th book in the series

[tw: rape mention, child loss] And when I do explain it, it’s either -I was sexually assaulted -I lost a child in a tragic way -Maybe I lost a sibling but it’s a sibling I was like a mother to. as a woman, rape & children are the only things that can happen to me

I don’t have any friends that aren’t other police ppl. If I’m in a relationship u better watch out because you’re so gonna die, relationship partner. I have a weird, fraught relationship with my family. Probably b/c they also lost babies tragically

For a good cop I make really bad decisions. I often end up taken in by the bad guy, who then explains to me what they’re doing and why like a super villain doing a monologue. U know I’m gonna survive though there are 6246 more books in the series

I’m not like those other girls, with their makeup and emotions. I don’t wear makeup but men are sure to think about how I don’t need it. I am 9 times out of 10 “not beautiful but striking” which means men want to fvck me but in like, a progressive way I guess

Of course you know if there’s a place I, Toughy McLadyCop shouldn’t go because it’s remote/hidden I will go there like the little baby Jesus is giving away free ice cream If I find a man attractive he’s probably a murderer

Maybe I have children. Oh well, I’ll spend most of my time leaving them with other people. Until they get taken by the murderer. Then I go on a McLadyCop rage bender that should get me fired but never does

I always eat crappy food but I don’t gain weight. The men around me apparently think about this a lot, as they mention it 422135213 times per book I am under the age of 40 because women over 40 are all old crones who reek of dust and sodden phone books

I feel a deep kinship with victims who are also young and pretty and maybe lost a child. Men don’t understand. Only women love children you see. I probably drink a lot of coffee because dude writers are boring

I probably live in a small town where there are so many murders. Just. Endless murders even though there are only like 50 people living here. Everyone thinks about my breasts. I also think about my breasts a lot

Anyway thank you for reading this book about me, Toughy McLadyCop. Now go buy the other infinity books in the series where the only character development I experience is probably marrying a dude.

[James Patterson deposits five million dollars in the bank, drinks champagne out of monkey’s skull, and allows a small, private chuckle]

@elle_em on Twitter (please donate to Elle’s cat orphanage in Spain)

the most unrealistic thing about the “women solving crimes” genre is that the women aren’t CONSTANTLY getting complaints from weird old men that “solving crimes is a man’s job” and “a woman’s place is in the home, not solving murders on a train.”

“women solving crimes” is the most sneakily subversive of genres because it teaches that women don’t need the police, they don’t even need a gun, all they need is their wits and maybe some rose-spray to spray in the murderer’s face.

@SketchesbyBoze

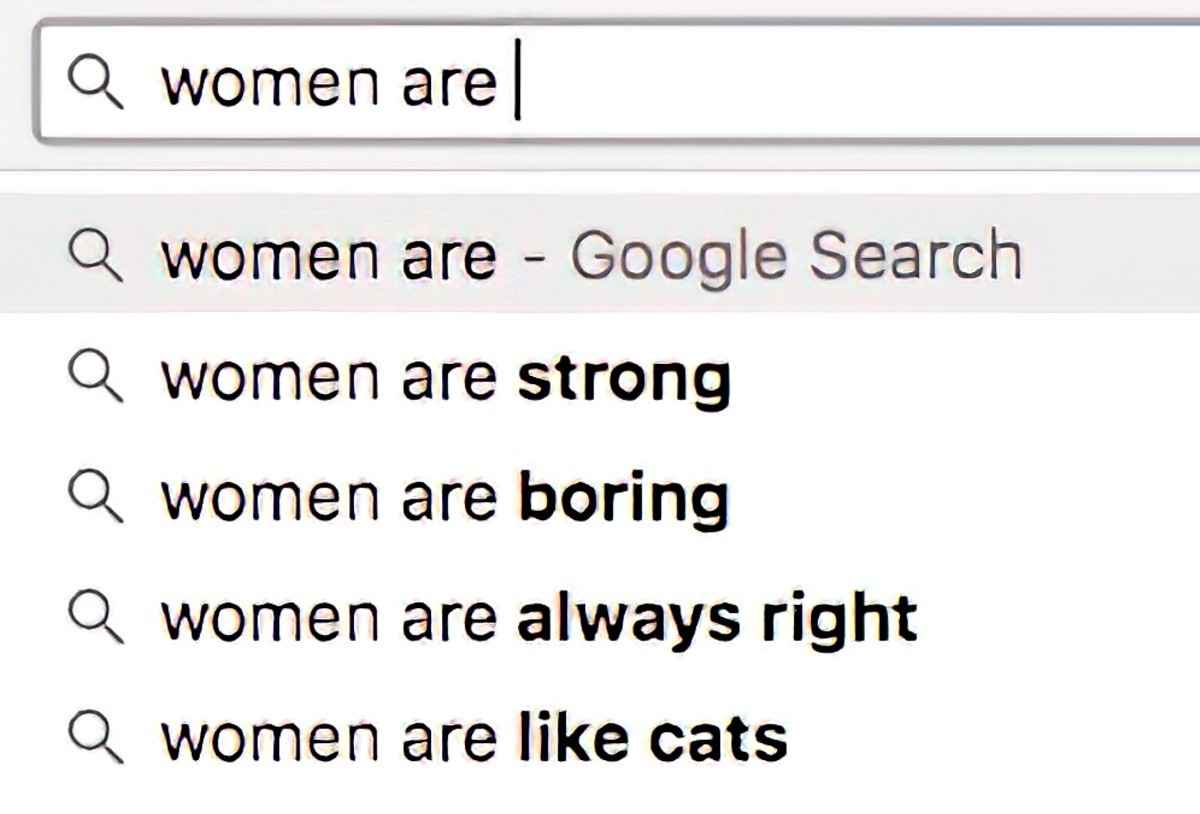

men writing about women’s bodies pic.twitter.com/VOjppnEpNl

— erin r bowles (@erinrbowles) September 9, 2021

Men writing about women: “Her name was aurora borealis…“

The Pudding analysed 20,000 books and discovered just how gendered adjectives are. Body parts are also gendered.

@GailSimone said on Twitter: “Describe a baked good like a cheap detective in a 1940s noir novel describes his new sexy client.” Responses here.

The famous As Good As It Gets movie clip on YouTube

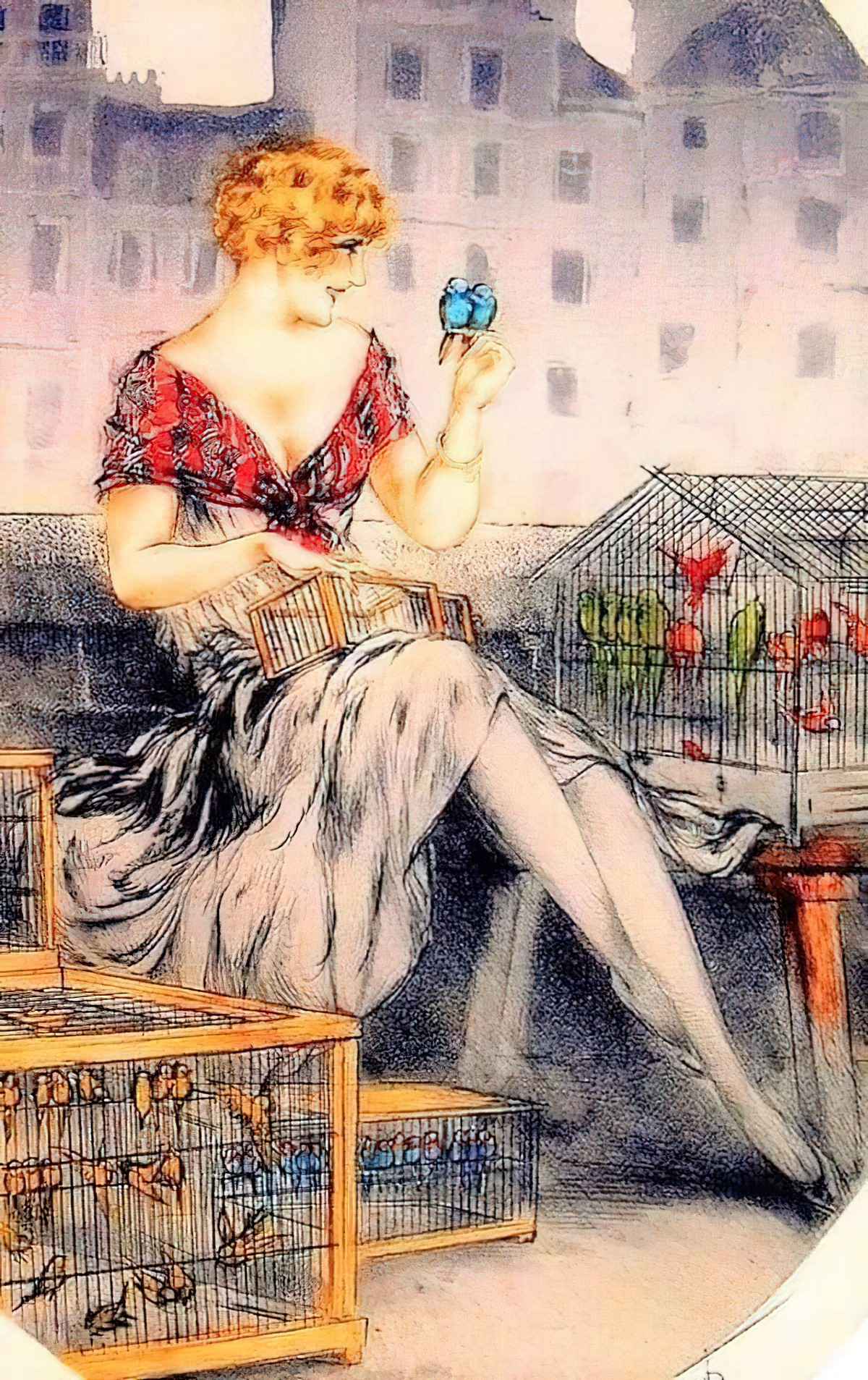

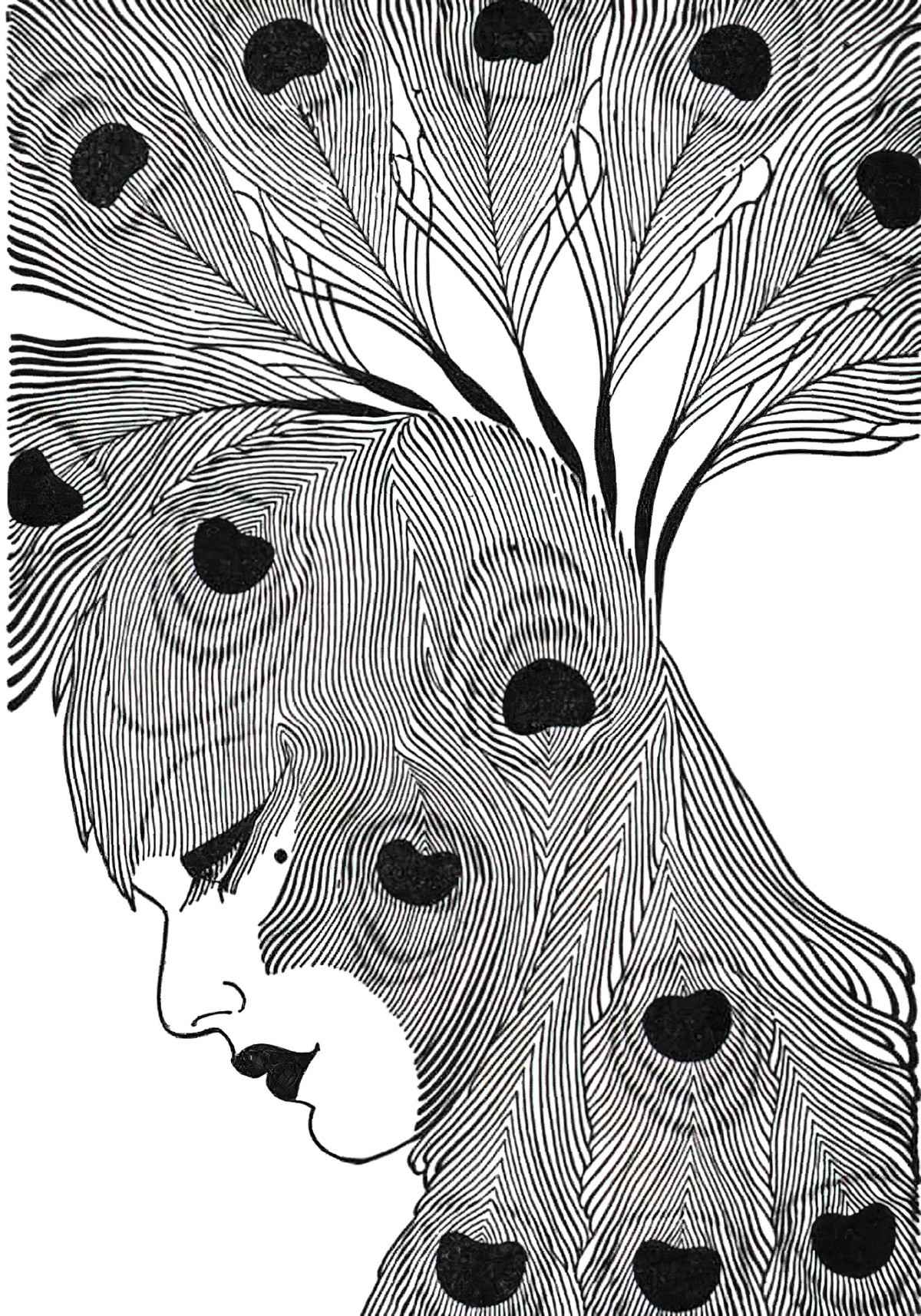

DESCRIBE A WOMAN AS BIRD

The cellist’s practicing annoyed everybody, especially the girl living directly above her who was pregnant. The girl was very nervous and seemed to be having a hard time. Her face was meager above her swollen body, her little hands delicate as a sparrow’s claws. The way she had her hair skinned back tightly to her head made her look like a child.

“Court in the West Eighties” by Carson McCullers

There was touch of the bird about her, of the jay, blue-green, light, vivacious, though she was over fifty, and grown very white since her illness.There she perched, never seeing him, waiting to cross, very upright.

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

She was so little. Like a bird. And some days she looked like she was going to break. Or get shot out of the sky and fall down dead.

description of the mother in You May Already Be A Winner, MG novel by Ann Dee Ellis (2017)

She was a little woman, with brown, dull hair very elaborately arranged, and she had prominent blue eyes behind invisible pince-nez. Her face was long, like a sheep’s, but she gave no impression of foolishness, rather of extreme alertness; she had the quick movements of a bird. The most remarkable thing about her was her voice, high, metallic, and without inflection; it fell on the ear with a hard monotony, irritating to the nerves like the pitiless clamour of the pneumatic drill.

description of a Christian woman living in Samoa, “Rain” by W. Somerset Maugham

In contrast, Skellig by David Almond inverts gender tropes in several ways. His young male character brings food to and nurtures another male character. Males serving food anywhere in literature is hard to find, let alone to another male. The gender trope is also broken in that we have a male character described as a bird rather when it’s usually reserved for females. Less remarkable perhaps that the analogy is an owl. Of all the birds, owls are probably the most masculine, owing to their academic, learned, wise anthropomorphism. (In non Western cultures though, owls are connected to the night, the moon and therefore to femininity.)

In the 2017 MG novel Furthermore by Tahereh Mafi, Alice receives a dress which has a collar of feathers. This dress makes her feel like she can fly. The dress ‘made her miss the quiet moments she’d once resented, dancing alone in the forest, her heartbeats synchronised to the sounds of the world. This is connected to the more basic cultural idea that women are more connected to nature, owing to our bodily functions which seem gory and base, whereas men are closer to god. That is perhaps an exaggeration and oversimplification when talking about gender differences in modern societies, but historically it’s very accurate. In this book, the main character of Alice has an affinity to nature, and her transformation into a bird-like creature brings her even closer to the forest and the creatures who live within. See also: The Symbolism of Flight in Children’s Literature.

Taking a broader look at characters compared to birds in stories and it becomes clear that when any gender is compared to a bird, that character is vulnerable. If women are more commonly described as birds, that’s because women are more often portrayed as vulnerable.

Fly Me Home by Polly Ho-Yen (2017) is a magical realist middle grade novel in which two male characters are described as birds. The first is an elderly man with a childlike sensibility who can levitate. He may or may not be part of Leelu’s imagination. Eventually, Leelu goes on an urban journey to rescue her brother, who has been beaten up by bad people. This, too, is a gender inversion since historically it’s always the male gender saving the female gender.

[The older brother] lay unmoving, apart from one of his hands, which flickered with movement. His fingers flexed and trembled to their own rhythm; little flutterings that made me think of a bird’s wings beating in flight.

In Mad Men, Don Draper’s pet name for his first wife, Betty, if ‘Birdie’, which sounds a lot like ‘Bertie’ until you listen closely. This does play into a common heterosexual female desire, to feel much smaller than her male partner, and therefore protected. The problem for Betty is that she really is quite fragile and does need protecting from the world by a man.

I am no bird; and no net ensnares me; I am a free human being with an independent will.

Charlotte Brontë

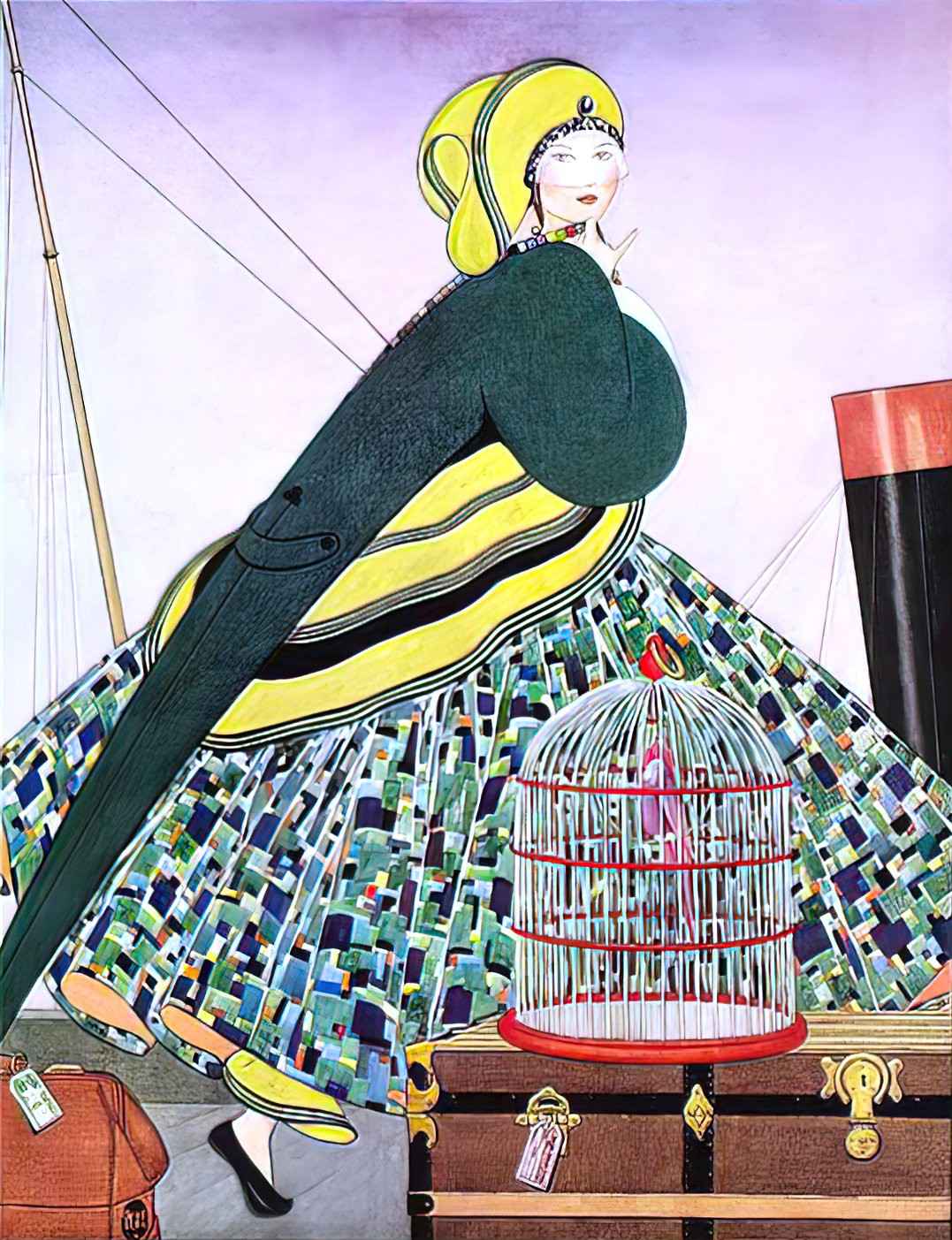

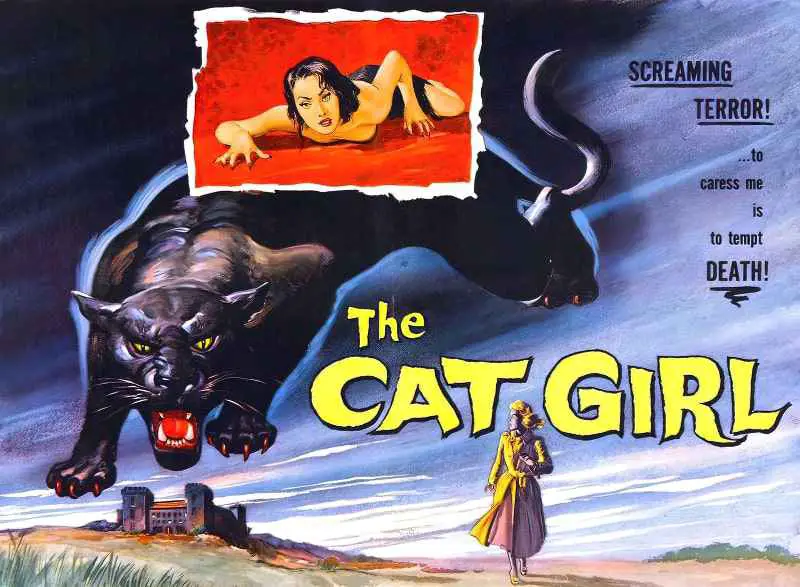

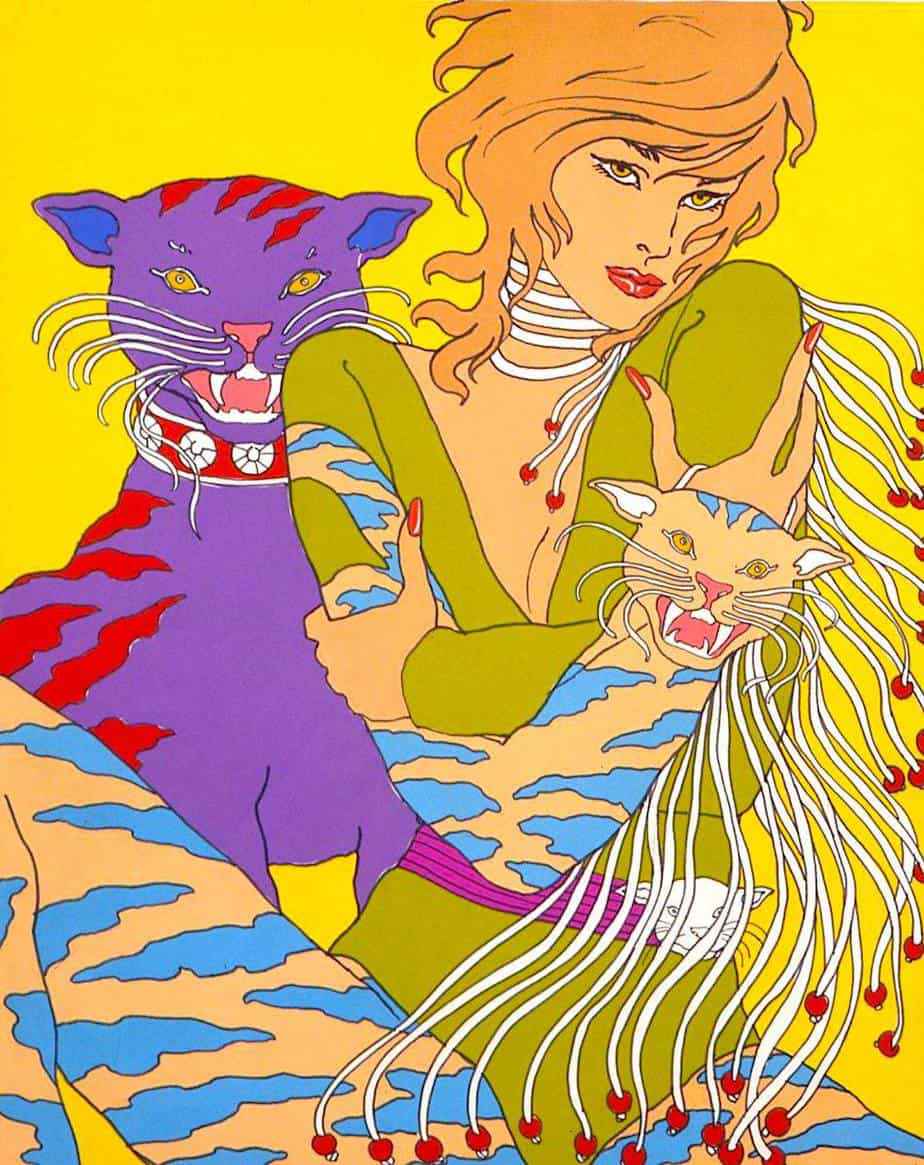

DESCRIBE A WOMAN AS A CAT

Her only gift was knowing people almost by instinct, she thought, walking on. If you put her in a room with someone, up went her back like a cat’s; or she purred.

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

In stories for adults, women are birds except when they’re in bed, in which they morph into cats. Purring, mewling and so on. More common in certain genres than others.

What about in children’s literature, which for obvious reasons is absent the sex scenes? (Sex is replaced by food in children’s stories. True story.)

Sometimes the comparison between girl and cat is quite subtle. Do you ever hear boys described as ‘stalking’ away in a huff? Oh sure, there are plenty of actual male stalkers in literature, and quite often they’re rewarded for their predatory behaviour by ending up with the girl, but only girls ‘stalk’ away, which is a weird descriptor when you think about it. How did stalk come to mean two opposite behaviours? When cats stalk their prey, they’re going towards the object, not away from it.

Cass shoves the contents of her tray into the trash and stalks away. Even though she didn’t say it, it’s obvious I’m the reason she’s upset.

— a lunchroom scene from The Peculiar Incident On Shady Street, MG horror by Lindsay Currie (2017). Notice that like pet cats, girls don’t show their feelings. We can tell exactly what they’re thinking from their body language. (Another dangerous ideology, but commonly underscored in fiction.)

Sometimes women are described as large cats. With irony noted, this article describes women as ‘savage’ in the title for daring to make fun of the way male authors describe female characters.

Carson McCullers, who describes a woman as a bird in “Court In The West Eighties”, subverts the gender trope by later describing a man as a cat: ‘He was dapper like a little cat — small, with a round oily face and large almond shaped eyes.’

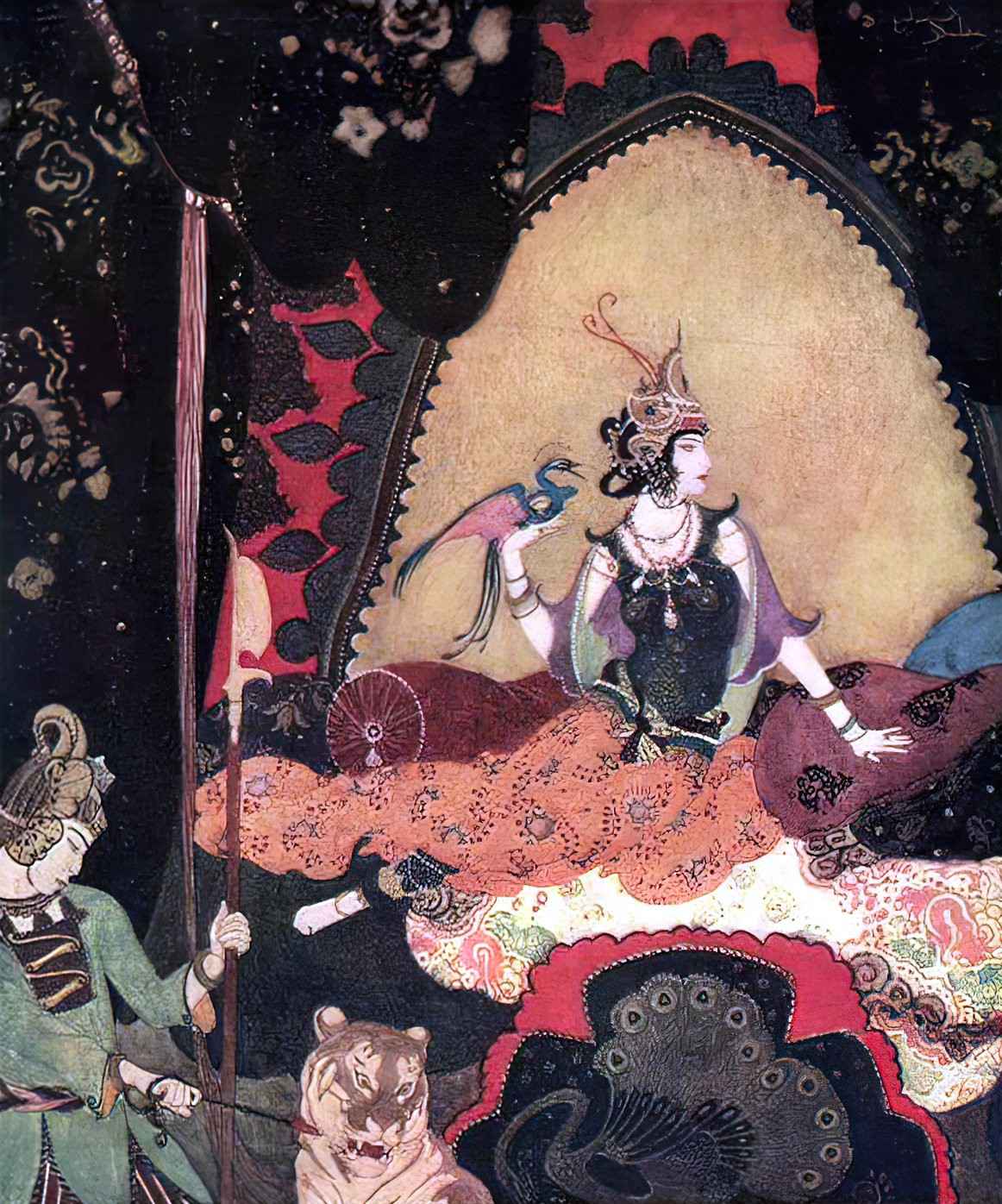

WOMEN AS UGLY OLD HAG, YET STRANGELY DESIRABLE SOMEHOW

Iris Murdoch’s husband wrote a biography of his late wife after she died. He describes picking her up for their first date:

The door opened. An apparition in what seemed a sort of flame-coloured brocade stood before me. I felt in some way scandalised: dazzled but appalled at the same time. All my daydreams, my illusions and preconceptions about the woman — the girl? the lady? — of the bicycle seemed to have torn away and vanished back into a past which I would still very much have preferred to be inhabiting, given the choice. But I had no choice. The person before me was exactly the same as the one riding the bicycle. I still thought her face homely and kindly, not in any conventional sense pretty or attractive, even if it was a strong face in its own blunt-featured snub-nosed way; and for me it was always mysterious too. But now I was seeing it as other people saw it. Although it was in no way conventional itself its trappings, so to speak, were now conventional. Their appearance disappointed me sadly. They seemed the sort of things that any girl would wear; a silly girl who had not the taste to choose her clothes carefully.

However, gentleman that he says he was, John Bayley fell into bed with Iris later than night and told her in a very sexy way, I’m sure, how he loved her snub-nose.

Later, John Bayley also manages to describe his late wife as a bird:

At happy moments she seems to find [words] more easily than I do. Like the swallows when we lived in the country. Sitting on the telephone wire outside our bedroom window a row of swallows would converse animatedly with one another, always, it seemed signing off each burst of twittering speech with a word that sounded like ‘Weatherby’, a common call-sign delivered on a rising note. We used to call them ‘Weatherbys’. Now I tease her by saying ‘You’re just like a Weatherby, chattering away.’

and a cat, though he overturns the trope somewhat:

The Alzheimer face is neither tragic nor comic, as a face can appear in other forms of dementia: that would suggest humanity and emotion in their most distorted guise. The Alzheimer face indicates only an absence: it is a mask in the most literal sense. That is why the sudden appearance of a smile is so extraordinary. The lion face becomes the face of the Virgin Mary, tranquil in sculpture and painting with a gravity that gives such a smile its deepest meaning.

In any case, John Bayley’s real life use of the trope leads me to question the extent to which men sum up their female dates, balancing their conventional beauty against their inevitable sexual allure, against the social capital their beauty will bring to the man when he claims her for himself and will be judged by her beauty in public. Women worry about our own looks, wondering if we measure up. Men, apparently, also worry about women’s looks, wondering if we’ll measure up.

The most insidious, distasteful thing about men and male characters (proxy male authors) getting caught up in this psychological minefield around beauty standards is the idea that men should be congratulated for finding a non-model girlfriend sexually attractive regardless of her flaws, which are only flaws in his mind anyhow. Don’t nobody get no cookie for that.

A lot of white, male writers love this trope of the strangely alluring but scary woman. Ken Follett opens Pillars of the Earth with a mysterious young woman, who will soon jump our hero in the forest as he’s freshly grieving for the wife who Follett conveniently knocks off in childbirth:

She was a girl of about fifteen. When people looked at her they wondered why they had not noticed her before. She had long, dark brown hair, thick and rich, which came to a point in her wide forehead in what people called a devil’s peak. She had regular features and a sensual, full-lipped mouth. The old women noticed her thick waist and heavy breasts, concluded that she was pregnant, and guessed that the prisoner [about to be executed] was the father of her unborn child. But everyone else noticed nothing except her eyes. She might have been pretty, but she had deep-set, intense eyes of a startling golden colour, so luminous and penetrating that, when she looked at you, you felt she could see right into your heart, and you averted your eyes, scared that she would discover your secrets. She was dressed in rags, and tears streamed down her soft cheeks.

Pillars of the Earth, Ken Follett

Ken Follett is a big fan of the ugly woman who is nonetheless f*ckable, even if she’s old:

She had been famous, once, briefly. At the peak of the hippie era she lived in the Haight-Ashbury nieghbourhood of San Francisco. Priest had not known her then—he had spent the late sixties making his first million dollars—but he had heard the stories. She had been a striking beauty. She had made a record, reciting poetry against a background of psychedelic music with a band called Raining Fresh Daisies. […] That was a long time ago. Now she was a few weeks from her fiftieth birthday. Her figure was still generous, though no longer like an hourglass: she weighed a hundred and eighty pounds. But she still exercised an extraordinary sexual magnetism. When she walked into a bar, all the men stared. / Even now, when she was worried and hot, there was a sexy flounce to the way she paced and turned beside the cheap old car, an invitation in the movement of her flesh beneath the thin cotton dress, and Priest felt the urge to grab her right there.

The Hammer of Eden, Ken Follett. First detailed description of a woman character in the story.

It’s the ‘but’ that gets me. You find a woman sexually attractive or you don’t. What’s with all the buts? Are we to congratulate our male hero for finding her attractive despite everything? Is this a perverse kind of Save the Cat moment? Jeez, I think I just made a terrible connection there.

WOMEN AS FOOD PRODUCTS

Women of colour will tell you how often they are described as food products, especially hot beverages. (Cocoa, coffee, mocha…) Or food in general, especially sweet ones (caramel, toffee, carob, biscuit, chocolate, honey).

To avoid:

Giving a character almond-shaped eyes or coffee-mocha-latte-chocolate-hazelnut-caramel-cappuccino-colored skin. In fact, as a general rule, writers seeking inspiration solely from Starbucks menus probably need to dial down the caffeine.

Sara Hockler

Yet we do still see this in modern children’s books, and I’d like to draw your attention to the gendered nature of it.

Nina’s huge eyes are focused on me now, like saucers of brown paint. If I had to classify them in pastel terms, I’d say they’re cocoa bean.

The Peculiar Incident On Shady Street by Lindsay Currie (2017)

Girls do look different from boys. Girls wear different clothes, different hair, move differently, and eventually there’s sexual dimorphism. But don’t default to a long history of tropes when describing girls and young women, because your story stands on the shoulders of every story which came before.

And that isn’t always a good thing.

Header painting: Robert Payton Reid – Love’s Messenger.