Below you’ll find examples of churches from literature followed by churches in art and illustration.

A CHURCH FROM CLASSIC HORROR

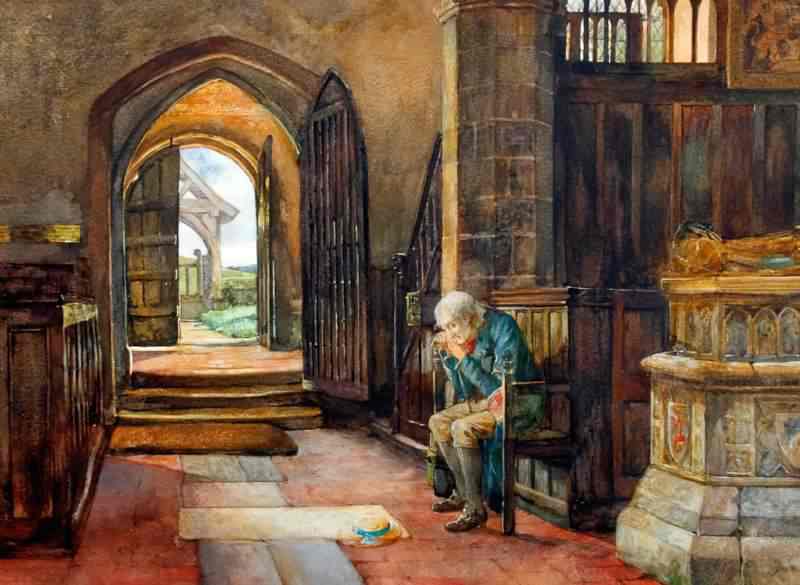

The church was a large and lonely one, and we loved to go there, especially upon bright nights. The path skirted a wood, cut through it once, and ran along the crest of the hill through two meadows, and round the churchyard wall, over which the old yews loomed in black masses of shadow. This path, which was partly paved, was called “the bier-balk,” for it had long been the way by which the corpses had been carried to burial. The churchyard was richly treed, and was shaded by great elms which stood just outside and stretched their majestic arms in benediction over the happy dead. A large, low porch let one into the building by a Norman doorway and a heavy oak door studded with iron. Inside, the arches rose into darkness, and between them the reticulated windows, which stood out white in the moonlight. In the chancel, the windows were of rich glass, which showed in faint light their noble colouring, and made the black oak of the choir pews hardly more solid than the shadows. But on each side of the altar lay a grey marble figure of a knight in full plate armour lying upon a low slab, with hands held up in everlasting prayer, and these figures, oddly enough, were always to be seen if there was any glimmer of light in the church. Their names were lost, but the peasants told of them that they had been fierce and wicked men, marauders by land and sea, who had been the scourge of their time, and had been guilty of deeds so foul that the house they had lived in—the big house, by the way, that had stood on the site of our cottage—had been stricken by lightning and the vengeance of Heaven. But for all that, the gold of their heirs had bought them a place in the church. Looking at the bad hard faces reproduced in the marble, this story was easily believed.

Man-Size in Marble by E. Nesbit

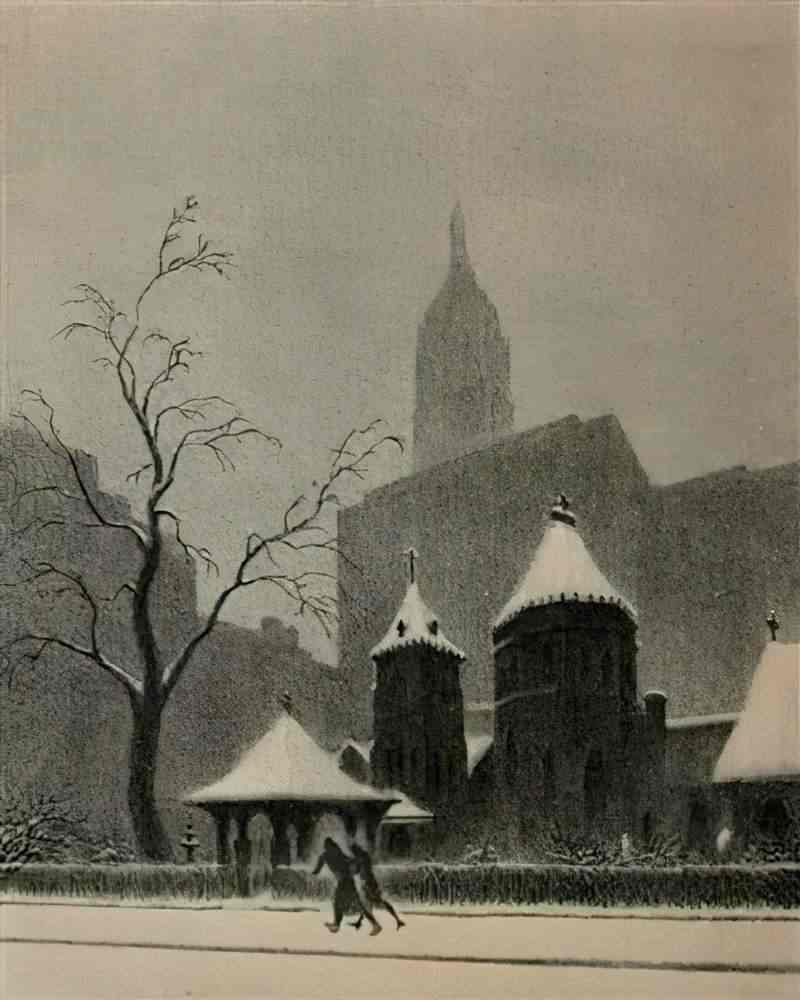

A NEW YORK CITY CHURCH FROM A CONTEMPORARY NOVEL

The cathedral across the way is stony and grand, out of place in these cluttered, low-rise streets. In the night dark it’s somehow a shadow.

Mother In The Dark, a 2022 novel by Kayla Maiuri

A 1930S CHURCH

They lodged her in a little cell-like room adjoining a small chapel dedicated to the Magdalen, a darksome and forbidding little shrine with vaulted ceiling and a window scarce a hand-breadth wide, stained, rather than illumined, by the red glow of a vigil lamp.

“The Lady of the Bells”, Weird Magazine, 1939

ST JAMES IN LIVERPOOL

The Oratory of St James’s Cemetery in Liverpool has no windows along the whole length of its outer walls. Only a long rectangular skylight, its leaded panes half-mossed over, lets the winter sun reach down and touch the white marble statues staring blankly inside. A mortuary chapel, but long closed up, its coffered ceiling and tall, carved columns are mostly in shadow. Years ago, as the great homes of the city were pulled down stone by stone, the monuments of proud families (monuments of terracotta and marble and bronze) were hoisted here and locked away, and so the wealth of the city – wrenched from far-off lands and furnished from blood – was hidden, and so forgotten.

And as the years went by, other things were hidden, too. Some (like the terraced slums of the poor and their washhouses) were razed, others (the orphanages and workhouses, the asylums and homes for the destitute) were emptied one by one, turned by sharp-suited businessmen into flats or bars or restaurants, where the names of the dead, engraved in plaques on newly pointed walls, were the climbing holds of a city once again dragging itself up out of its own grave. And so the churches and crypts were closed, and the docks shut down, and the shackles shipped and left on other shores, and the subterranean tunnels and the catacombs were filled in with stones, and the quarry was planted with oaks and with sycamores and with the bodies of the dead. And it was in this way that the ghosts of the city were parcelled off, ushered from the streets into derelict buildings, made to stand in exhibition cases, hurried into the pages of books and diaries, and folded away. For, after all, ghosts can only live in the darkness; and once the dark places are closed up, their cast-iron locks bolted fast, it is easy for those who do not live with them to pretend that ghosts do not exist at all.

Past midnight, one mid-January, standing in the church gardens, I felt the wind blow up from the River Mersey, weighted with Atlantic salt. It blustered up to the city, battering the red bricks of the warehouses on the dock, rattling the barred doors of the pump-house and the locks of the customs house. I heard it rush south-east between the empty units along St James’s Street, clapping the tattered flags of the old sailors’ church, and spinning frantically in the bell-turret of St Vincent’s. It rushed up the steep junction of Parliament Street, past the new-builds, over the waiting cars at the traffic lights, and there scurried down the tree-tunnelled sandstone path into the cathedral cemetery, resting, finally, in a swirl of leaves and a ripple of the spring water by the catacombs, unseen by anyone except a carved angel weeping over a nineteenth-century grave, and the lone figure of a man – me – kneeling and drinking from the water flowing in runnels down the old cemetery wall.

the opening to All Down Darkness Wide, a memoir by Seán Hewitt (2022)

AN 1800S CATHOLIC CHURCH

In the distance a cemetery of wooden crosses was scattered about the hillside, as if the Spanish had once spilled a bucket of Catholicism over the land. At the old mission church in the plaza, a white cross leaned left and the air sounded with the squawking of sparrows and wrens. Desiderya left the pink-hued morning and entered the church, blessing herself and the baby with holy water at the door.

[…]

Deeper inside the chapel, several young women were on their hands and knees sweeping the floor with horsetail brushes. Dried rose petals were piled around them, and at the altar was a clay statue of La Virgen de Guadalupe, dressed in red silk. The young women were preparing her Feast Day, and the church smelled of incense and blue sage and the copal traded and carried from 1,400 miles south in Mexico City.

Woman of Light, a 2022 novel by Kali Fajardo-Anstine

ST CHRISTOPHERS

I want to describe the church now, and Miss Isabel. An unpretentious nineteenth-century building with large sandy stones on the façade, not unlike the cheap cladding you saw in the nastier houses—though it couldn’t have been that—and a satisfying, pointy steeple atop a plain, barn-like interior. It was called St. Christopher’s. It looked just like the church we made with our fingers when we sang:

Here is the church

Here is the steeple

Open the doors

There’s all the people.

The stained glass told the story of St. Christopher carrying the baby Jesus on his shoulders across a river. It was poorly done: the saint looked mutilated, one-armed. The original windows had blown out during the war. Opposite St. Christopher’s stood a high-rise estate of poor reputation, and this was where Tracey lived. (Mine was nicer, low-rise, in the next street.) Built in the sixties, it replaced a row of Victorian houses lost in the same bombing that had damaged the church, but here ended the relationship between the two buildings. The church, unable to tempt residents across the road for God, had made a pragmatic decision to diversify into other areas: a toddlers’ playgroup, ESL, driver training. These were popular, and well established, but Saturday-morning dance classes were a new addition and no one knew quite what to make of them. The class itself cost two pounds fifty, but a maternal rumor went round concerning the going rate for ballet shoes, one woman had heard three pounds, another seven, so‑and‑so swore the only place you could get them was Freed, in Covent Garden, where they’d take ten quid off you as soon as look at you—and then what about “tap” and what about “modern?” Could ballet shoes be worn for modern? What was modern? There was no one you could ask, no one who’d already done it, you were stuck. It was a rare mother whose curiosity extended to calling the number written on the homemade flyers stapled to the local trees. Many girls who might have made fine dancers never made it across that road, for fear of a homemade flyer.

Swing Time, a 2017 novel by Zadie Smith

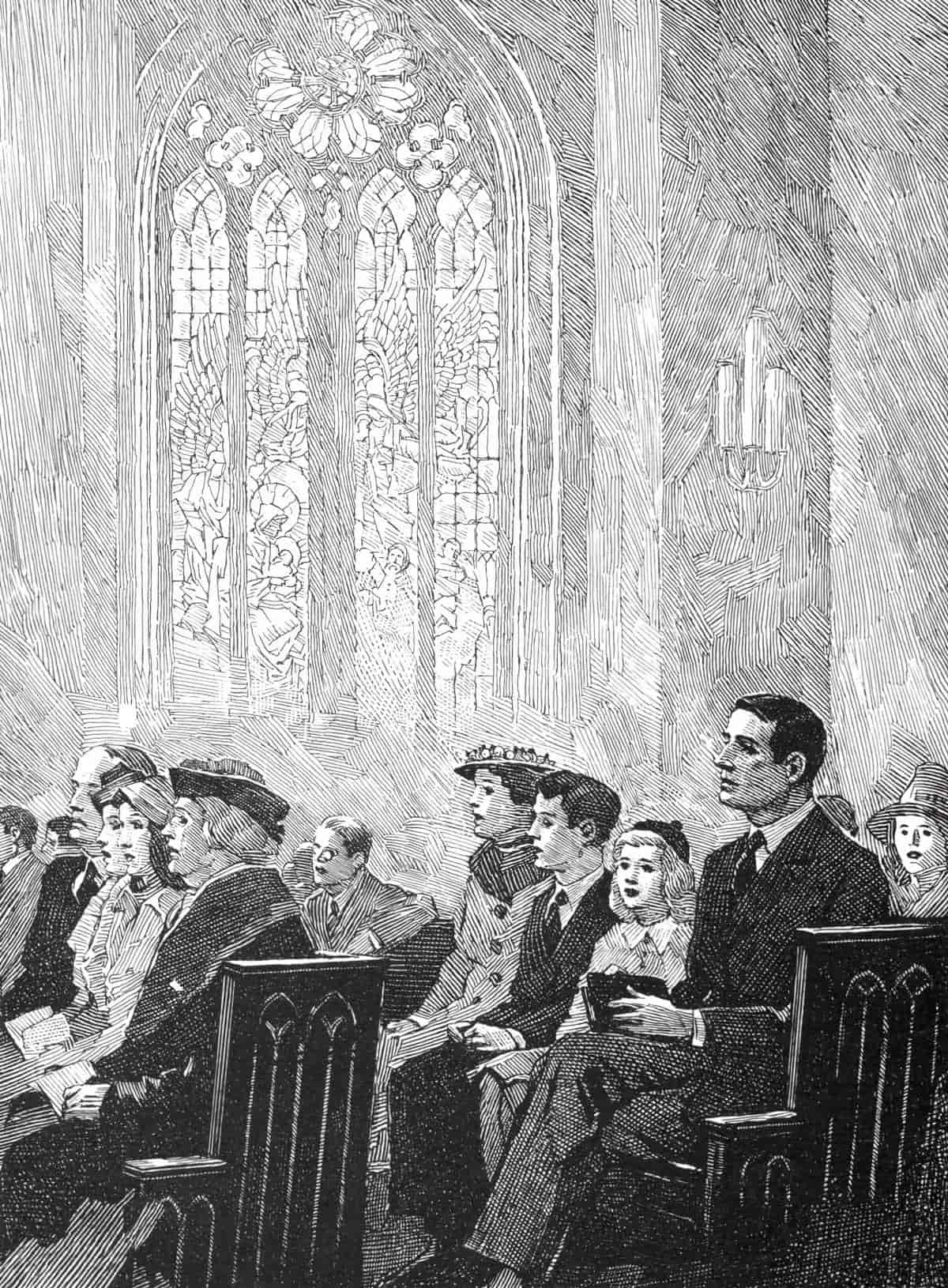

A NEW YORK CITY CHURCH (THE INSIDE) (LATE 20TH CENTURY)

“Infidel does not cover what I am,” I said.

“Now, now,” Louis said. “No melodrama. God loves us in our sins. Be a good girl. Take a deep breath and move.’

He gave me a little shove and I flew up the stairs and into the chapel. The last light came through the stained-glass windows, but the rest of the chapel was dim. The altar was lit with candles. I was immediately overcome with that undeniable, elevating melancholy so many people feel in a religious setting. I found myself sitting in a pew, staring in panic at the row of books in front of me: the hymnal, the supplement to the hymnal, a book of canticles, the Book of Common Prayer, and a paperbound book with the seminary’s name stamped on it, which when opened revealed itself to be full of hand-transcribed music.

“What am I supposed to do?” I said.

“Just look at the nice pictures in the windows and then stand when I stand and kneel when I kneel.”

“Kneel?” I said. “Do I have to kneel?”

Laurie Colwin, “Evensong”, The New Yorker, April 17, 2023

A CHURCH IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA CONNECTED TO RECENT MURDERS IN A CRIME NOVEL

MARTIN WALKS OUT BEFORE THE DAWN, THE AIR COOL AND THE SKY MUTED, finding his way through deserted streets to the epicentre of his story: St James. He stands before the church as the sun lifts from the horizon and sends shafts of golden light through the branches of the river red gums. He’s seeing it for the first time, but the building is familiar nevertheless: red brick and corrugated-iron roof, raised ever so slightly above the surrounding ground, half a dozen steps leading up to a utilitarian oblong of a building, its purpose suggested by the arch of its portico, the pitch of its roof and the length of its windows, and confirmed by the cross on its roof. A rudimentary belltower stands to one side: two concrete pillars, a bell and a rope. ST JAMES: SERVICES FIRST AND THIRD SUNDAYS OF THE MONTH—11 AM, says the sign, black paint on white. The church stands alone, austere. There is no surrounding wall, no graveyard, no protective shrubs or trees.

Martin walks the cracked concrete path to the steps. There is nothing to indicate what occurred here almost a year ago: no plaque, no homemade crosses, no withered flowers. Martin wonders why not: the most traumatic event in the town’s history and nothing to mark it. Nothing for the victims, nothing for the bereaved. Perhaps it’s too soon, the events still too raw; perhaps the town is wary of sightseers and souvenir hunters; perhaps it wants to erase the shooting from its collective memory and pretend it never happened.

Scrublands by Chris Hammer (2018)

FURTHER READING

A History of the Church through its Buildings

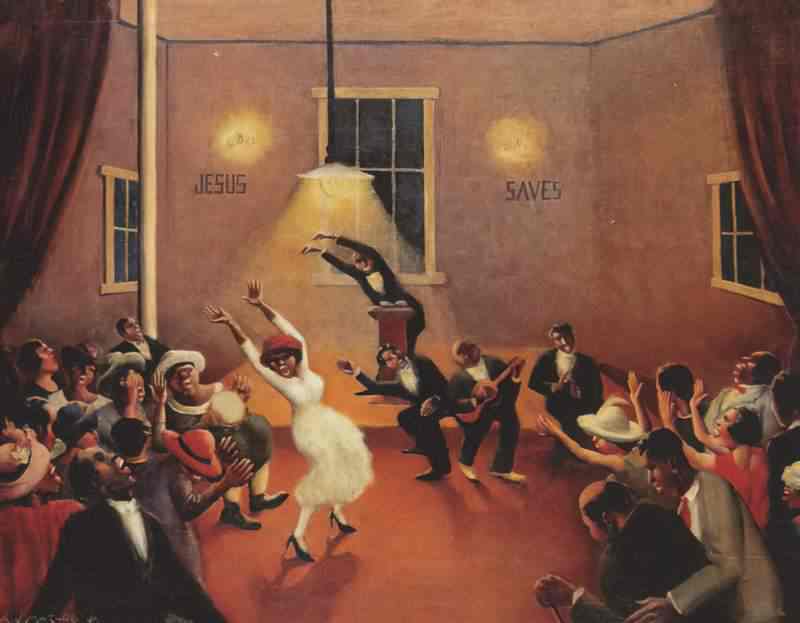

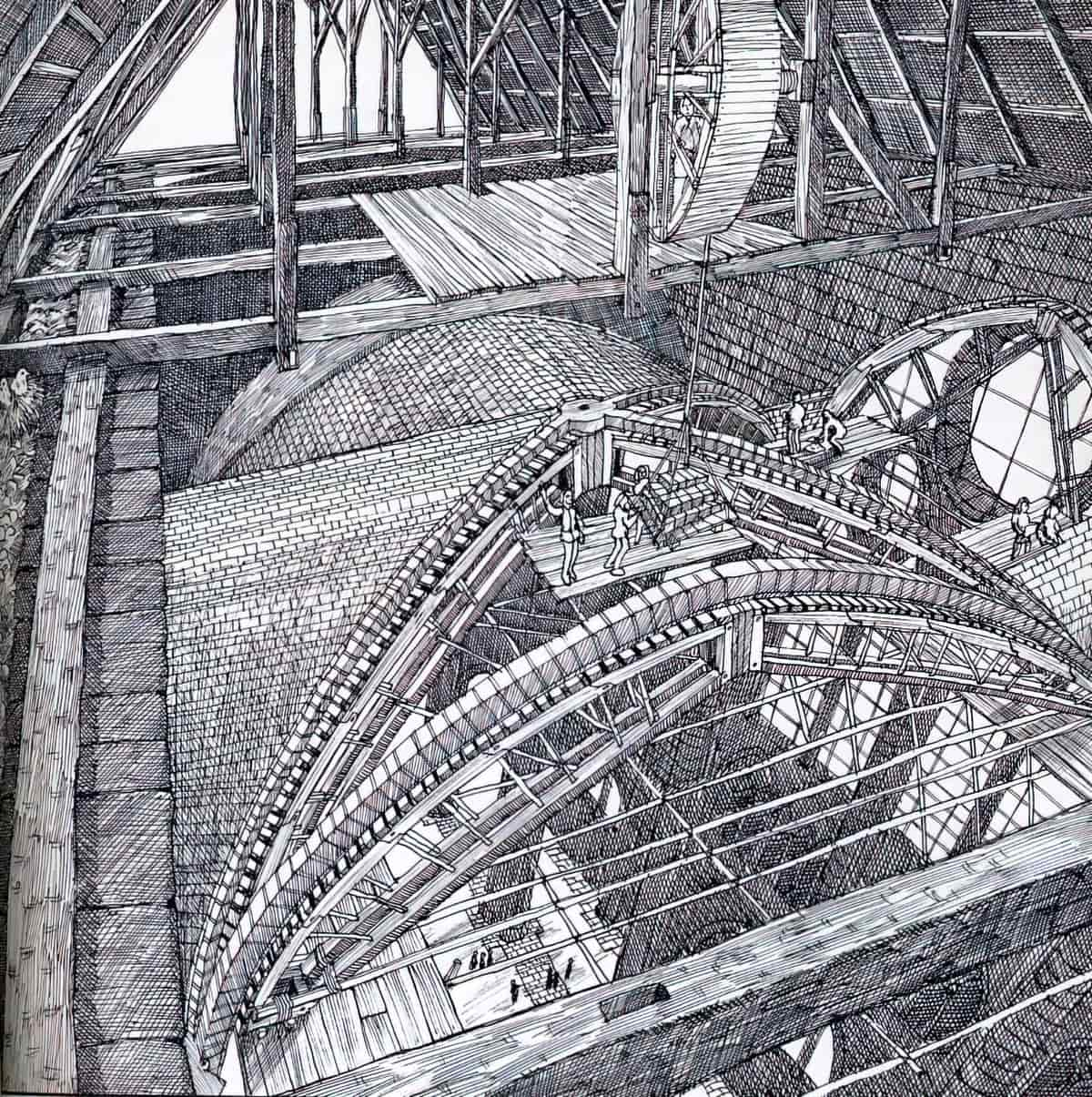

A History of the Church through its Buildings (Oxford University Press, 2021) by Allan Doig takes the reader to meet people who lived through momentous religious changes in the very spaces where the story of the Church took shape. Buildings are about people, the people who conceived, designed, financed, and used them. Their stories become embedded in the very fabric itself, and as the fabric is changed through time in response to changing use, relationships, and beliefs, the architecture becomes the standing history of passing waves of humanity.

This process takes on special significance in churches, where the arrangement of the space places members of the community in relationship with one another for the performance of the church’s rites and ceremonies. Moreover, architectural forms and building materials can be used to establish relationships with other buildings in other places and other times. Coordinated systems of signs, symbols, and images proclaim beliefs and doctrine, and in a wider sense carry extended narratives of the people and their faith.

Looking at the history of the church through its buildings allows us to establish a tangible connection to the lives of the people involved in some of the key moments and movements that shaped that history, and perhaps even a degree of intimacy with them. Standing in the same place where the worshippers of the past preached and taught, or in a space they built as a memorial, touching the stone they placed, or marking their final resting-place, holding a keepsake they treasured or seeing a relic they venerated, probably comes as close to a shared experience with these people as it is possible to come. Perhaps for a fleeting moment at such times their faces may come more clearly into focus.

INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR AT NEW BOOKS NETWORK

The Suburban Church: Modernism and Community in Postwar America

After World War II, America’s religious denominations spent billions on church architecture as they spread into the suburbs. Gretchen Buggeln’s latest monograph, The Suburban Church: Modernism and Community in Postwar America (University of Minnesota, 2015), is richly illustrated history of mid-century churches in the Midwest that shows how architects and suburban congregations joined forces to create a new wave of modernist churches to reflect and shape developments in postwar religion–its ecumenism, optimism, and liturgical innovation, as well as its fears about staying relevant during a time of vast cultural, social, and demographic change. Gretchen Buggeln holds the Phyllis and Richard Duesenberg Chair in Christianity and the Arts at Valparaiso University in Indiana.

interview at New Books Network

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by Paul Kwaitkowski and Dr. Maria Aliberti-Lubertazzi. Paul is Mount Auburn Cemetery’s Wildlife Conservation and Sustainability Manager, and Maria is an adjunct faculty member at Rhode Island School of Design as well as an environmental scientist specializing in wetland and urban ecology. Together, we discuss the unique initiatives taking place at Mount Auburn in areas including environmental stewardship, wildlife management, and citizen science.

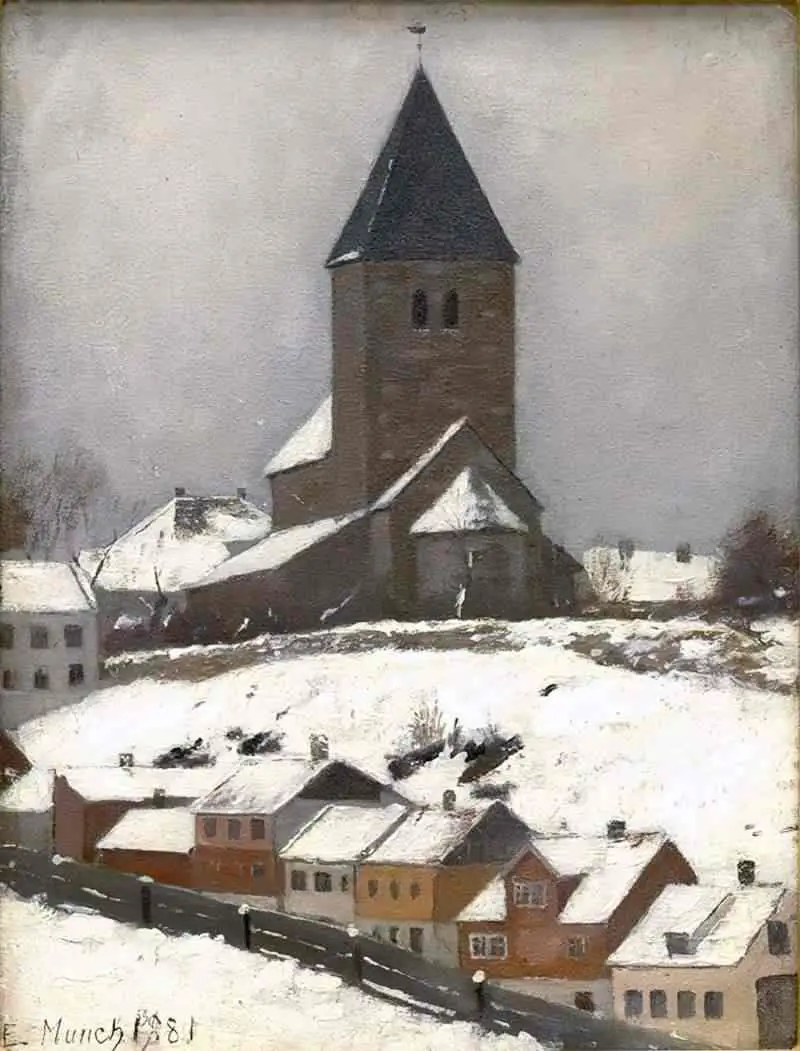

Header painting is by Elisabeth Sonrel (1874 – 1953)