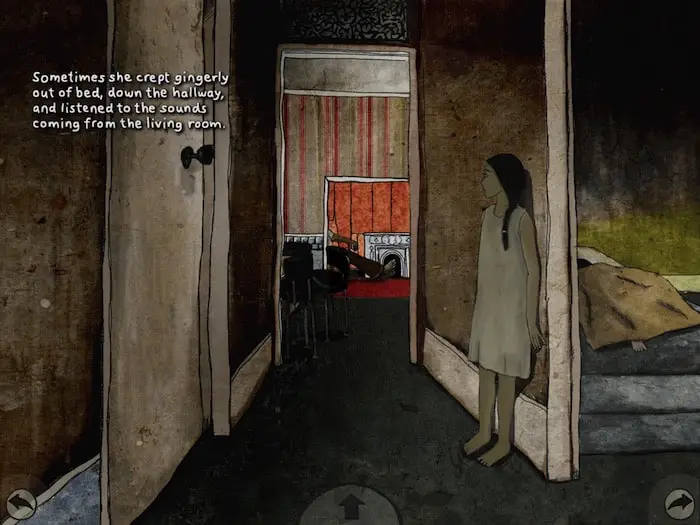

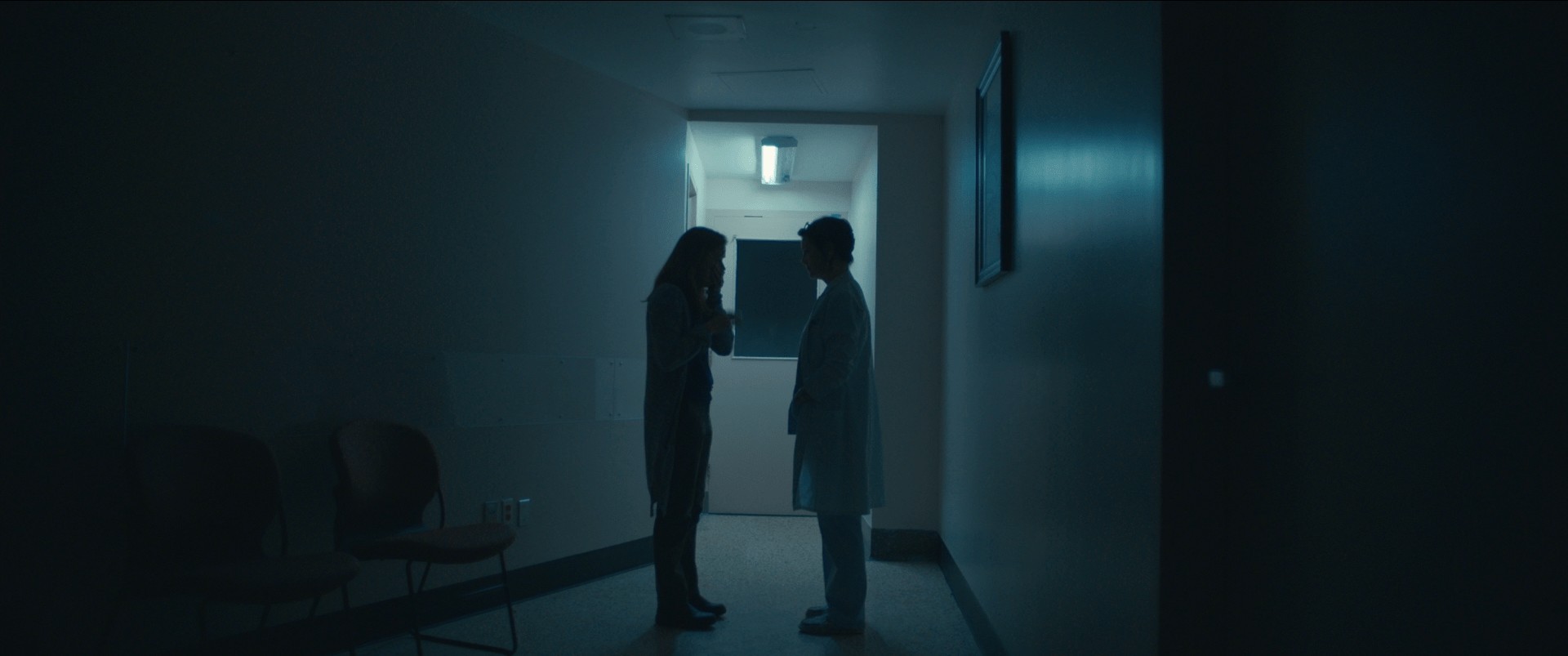

When storytellers focus on the hallways and passages of a building, look for metaphor. Take note of the width of the passageway: Narrow passages might represent the will to escape. Broad passages represent freedom and space.

The tunnel is the naturally occurring equivalent of the manmade passage. In houses, the passages, hallways and corridors are the liminal arenas, because they symbolise ‘inbetweenness’.

I love scenes set in hallways myself. In Midnight Feast, the hallway is a transitory space between reality and the freedom of imagination, functioning similarly to a fantasy portal.

CASE STUDY: HOUSE AS CONTROLLING MATRIARCH

The house described by Dawn French in her 2015 novel According To Yes is one of those huge, very old New York apartments that only the wealthy can afford. The main character is a ‘blithe spirit’ archetype similar to Mary Poppins who indeed arrives in New York from Wales as a nanny. She is a fish out of water. The house belongs to a stiff, upper-class, domineering woman and her ‘henpecked’ husband.

This corridor wasn’t intended to be dark, requiring internal lighting at all times. It’s the kind of space that is supposed to have light thrown into it by the leaving open of various doors all the way along. That doesn’t happen in this apartment under the rule of Glenn Wilder-Bingham. No. All doors remain neatly shut, and all the corridors off the main hallway, of which there are four, remain gloomily dark. It’s not that Glenn Wilder-Bingham is a vampire, it’s that she is a consummate control freak. If she could she would control all the light and doors in the world. As it is, she has to satisfy herself with the light and doors in this vast apartment only. Until she takes over the world, this will have to suffice.

Dawn French, According To Yes

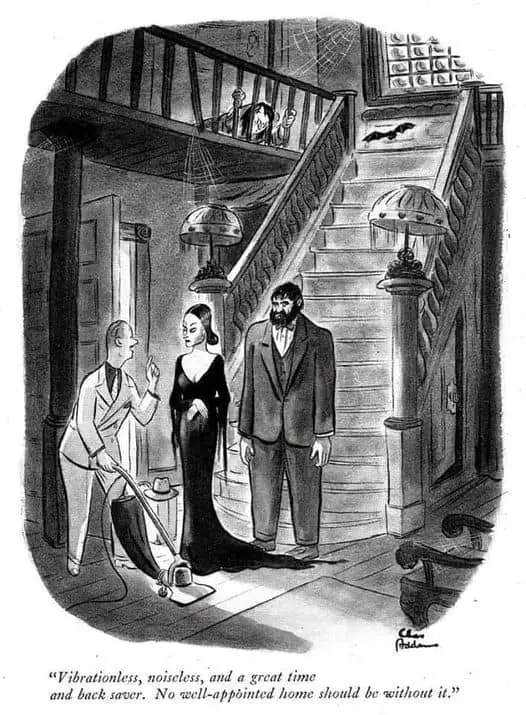

In this example, the house functions metaphorically as an architectural version of the matriarch — formidable, dark and unwelcoming. (This same metaphor — house as formidable matriarch — is used and abused in the children’s film Monster House.)

By saying that Glenn Wilder-Bingham is not a vampire, the narrator encourages the reader to think of her of exactly that (the technique of paralepsis). Vampires lead us to bats. The hallway in this house, therefore, functions as an urban cave.

CASE STUDY: WALLS AS PASSAGEWAYS

If you’ve ever had a rodent infestation you’ll know that rats and mice love ceilings and walls. The Rats In The Walls by Lovecraft makes the most of what was surely a familiar night-time sound before the invention of Rough On Rats (and subsequent safer poisons).

Neil Gaiman was perhaps thinking of that famous Lovecraftian short story when he conceived of The Wolves In The Walls, in which a child’s fear manifests in… well… it’s all in the title.

I wonder how common it is to imagine monsters in the walls of one’s house. Is it as common as Monsters Under The Bed? The particular horror of something residing in the walls is that it’s right there but you can’t see it. Once something is in the walls, it might as well be in the house.

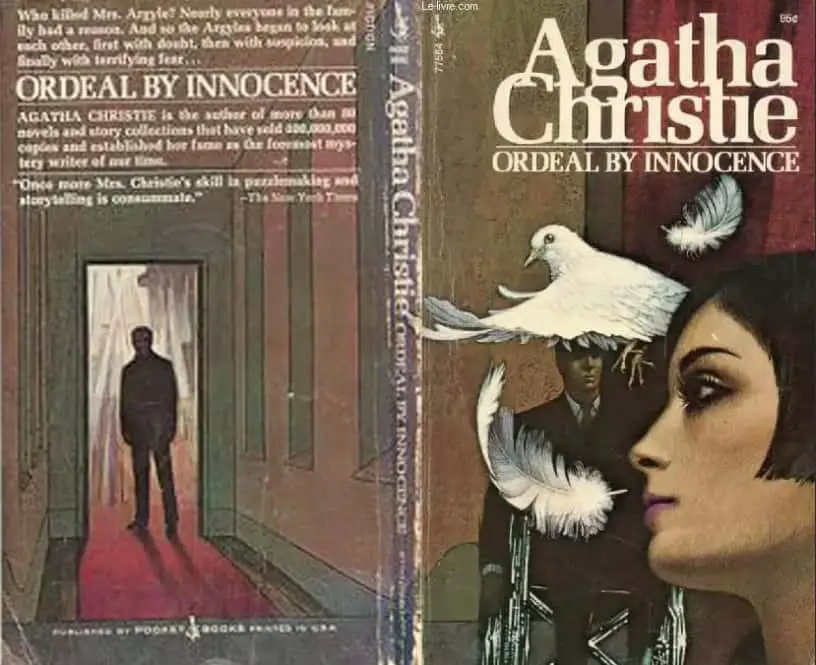

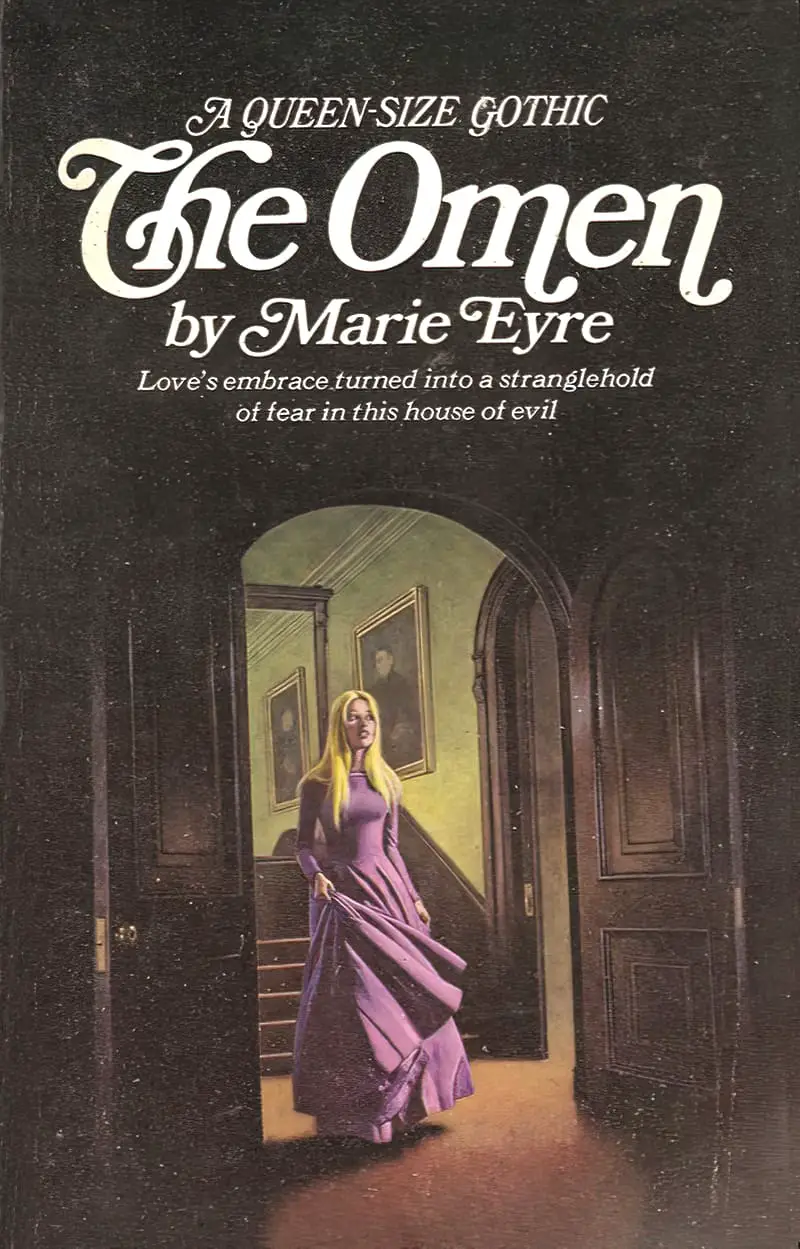

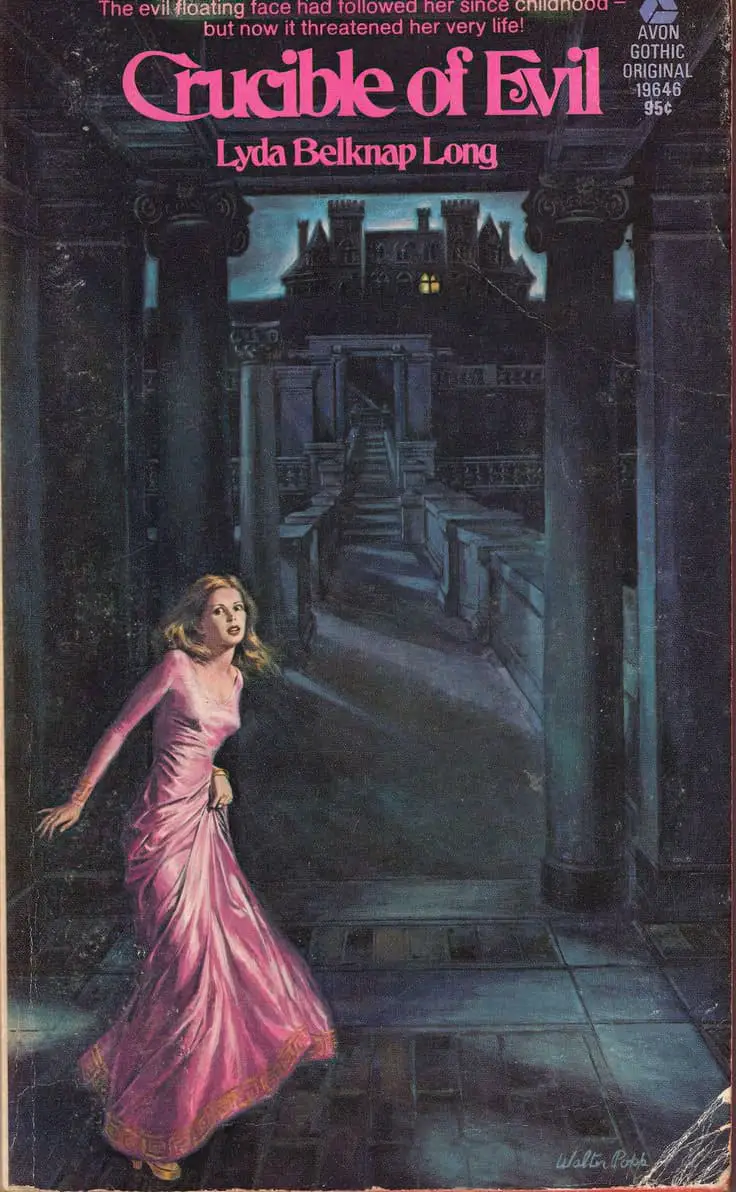

Beautiful young Jennifer Collins believed she was in love with handsome, aristocratic David Bryce. But when she visited David and his family for the first time at their old mansion on an isolated island, she suddenly felt as if David were a threatening stranger, and she were in deadly danger.

Now David’s loving words rang false in her ears as she fled through twisting corridors of hate . . . pursued by a faceless figure of vengeful evil . . . toward an abyss of horror from a past that would not die….

Supernatural crime horror comedy franchise Scooby-Doo is well-known for making heavy use of creepy corridors.

CASE STUDY: THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

Lost in the Wild Wood, Mole and Ratty stumble upon Badger’s house. Badger invites them in warmly.

[Badger] shuffled on in front of them, carrying the light, and they followed him, nudging each other in an anticipating sort of way, down a long, gloomy, and, to tell the truth, decidedly shabby passage, into a sort of a central hall; out of which they could dimly see other long tunnel-like passages branching, passages mysterious and without apparent end. But there were doors in the hall as well — stout oaken comfortable-looking doors. One of these the Badger flung open, and at once they found themselves in all the glow and warmth of a large fire-lit kitchen.

The Wind In The Willows

The home of a badger is called a ‘sett’.

Their setts are usually situated in or near small clearings in woodland or copses. Roughly 80% or so are in woodlands or hedgerows where trees or their roots provide the badger with some form of protection. The sett will be obvious to those who know what to look for, as the ground around the used entrances will probably be free of vegetation, and may be muddy and may show evidence of badger prints. There may also be evidence of latrines (holes in the ground) nearby, into which badgers do their poo.

Badgerland

The Badger of The Wind In The Willows is a Spirit archetype, a guide in the woods who saves Mole and Ratty from certain death. At a metaphorical level, Mole has entered the Wild Wood to get in touch with the most repressed part of himself. When Badger invites him further into it and leads him down all these branching passages, Kenneth Grahame is utilising the symbolic archetype of crossroads. Down here, Mole is going to be making an (off-the-page) moral decision about what comes next.

WHY ARE HALLWAYS CALLED HALLWAYS?

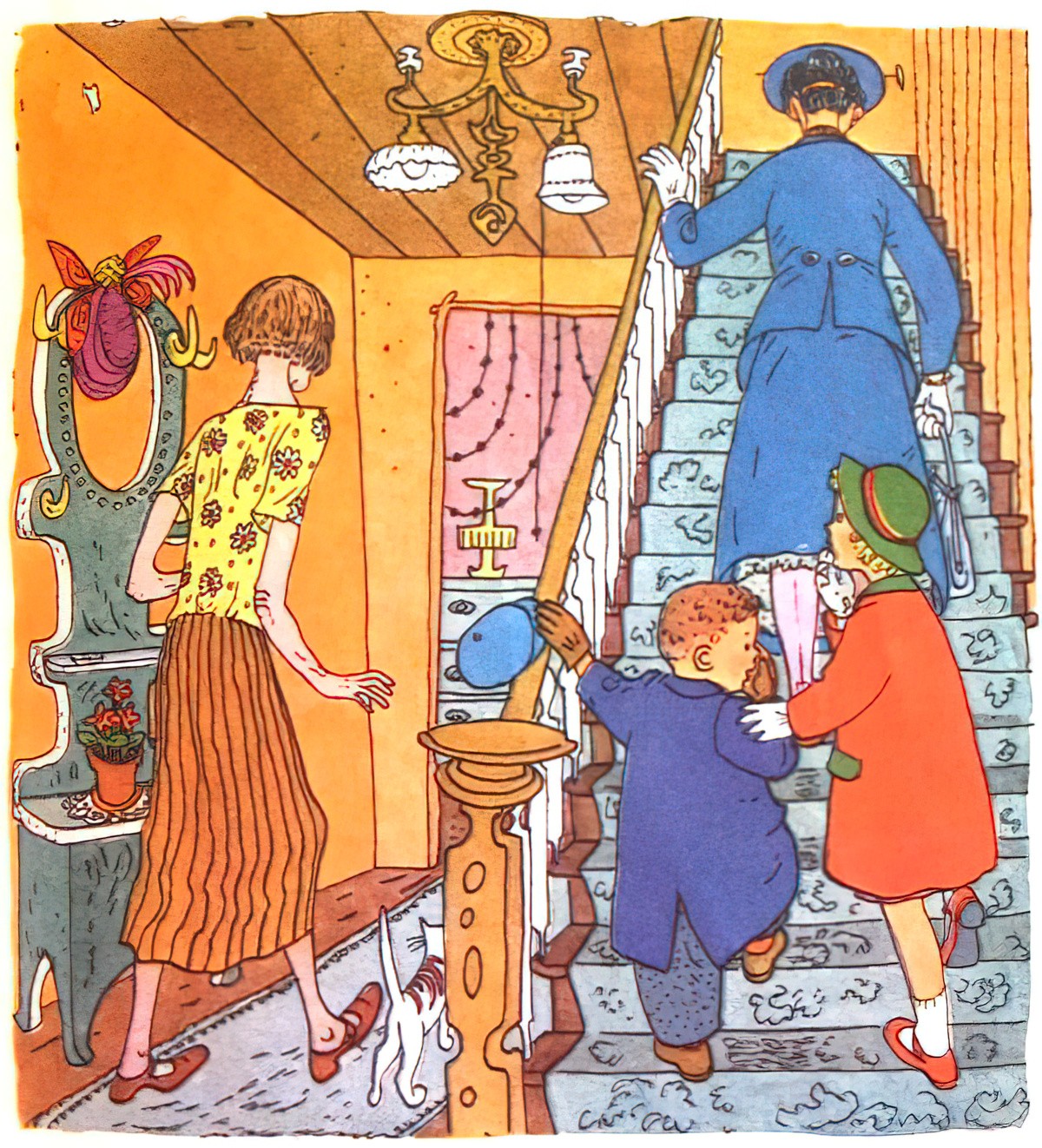

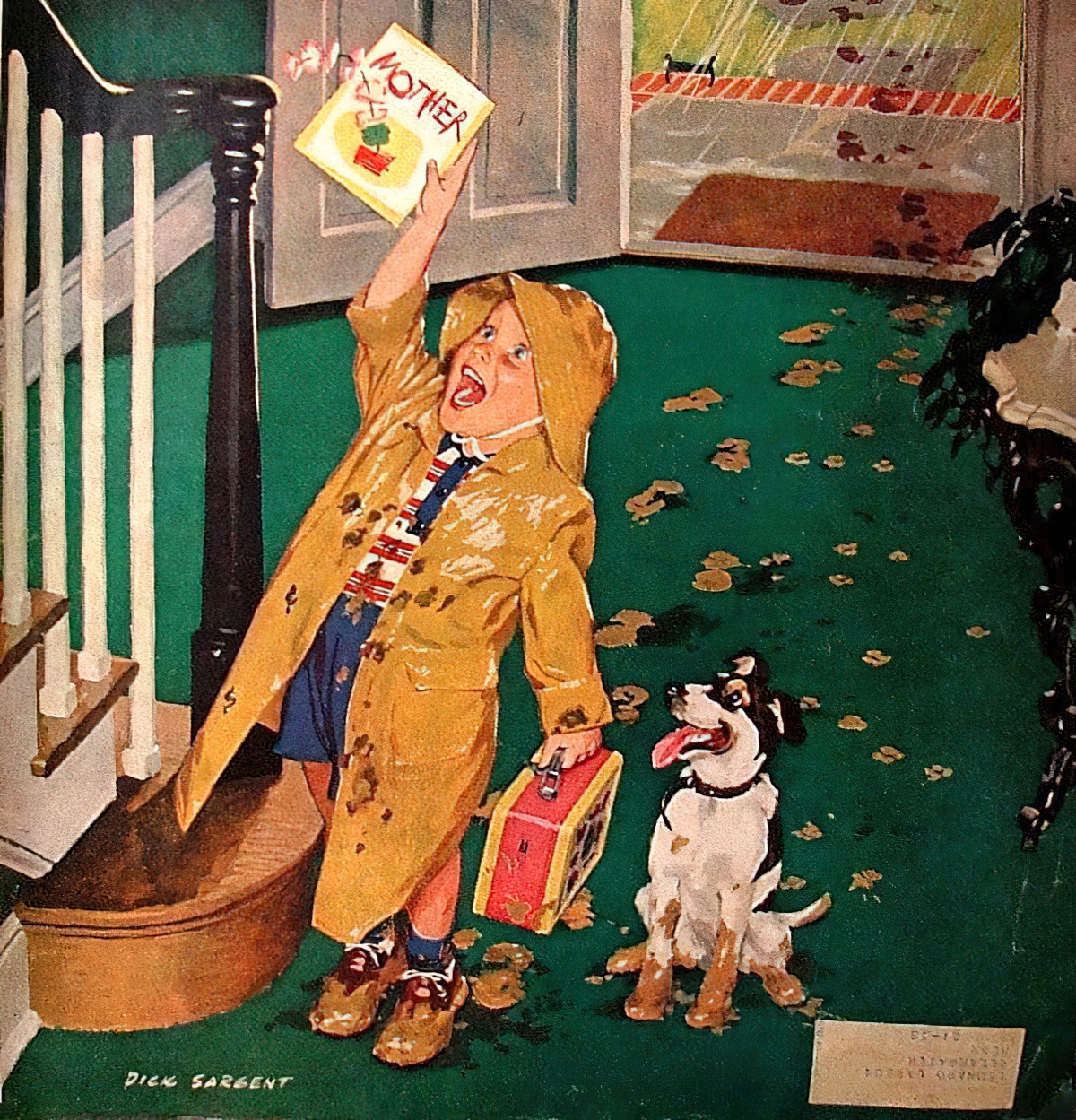

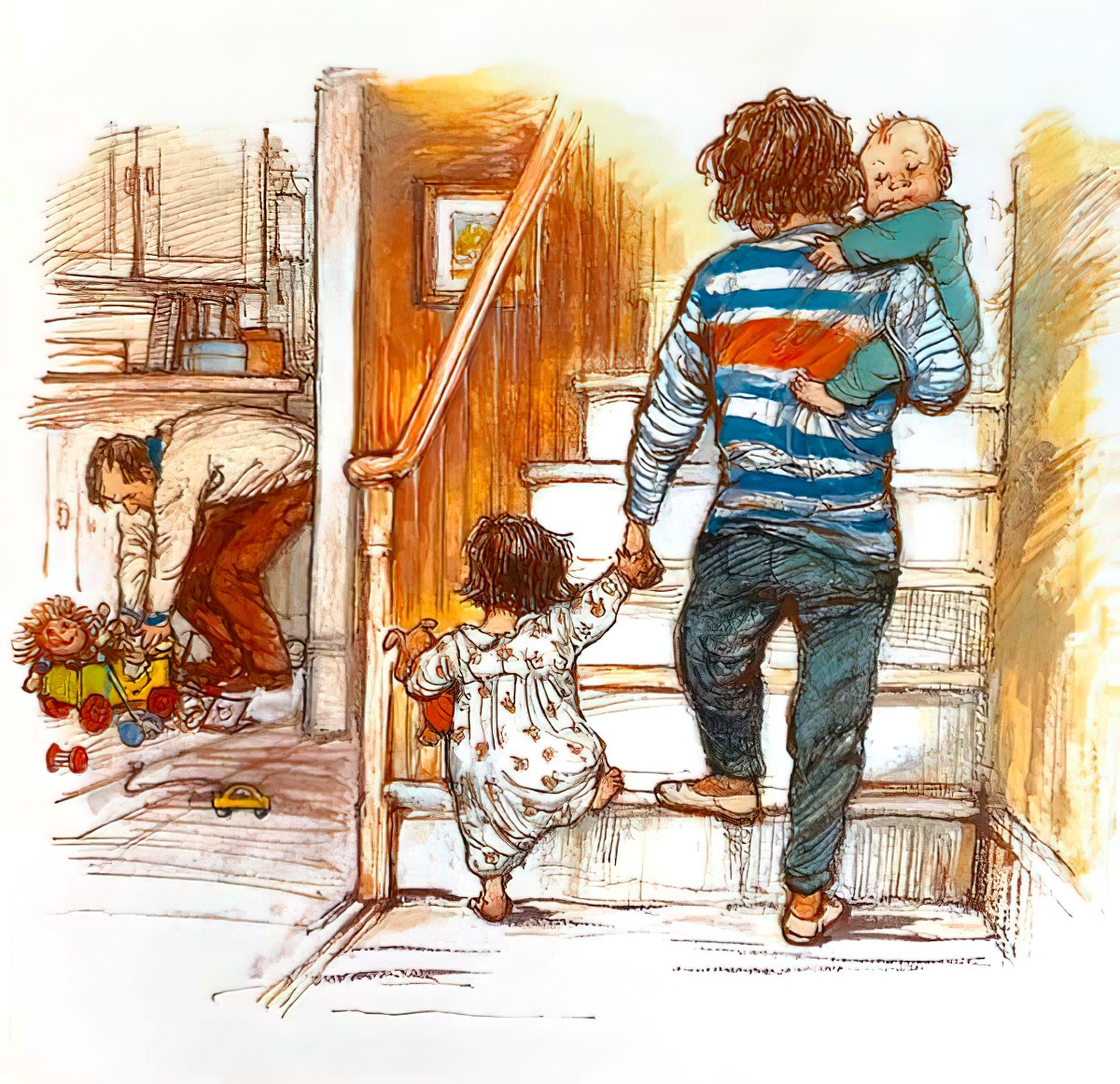

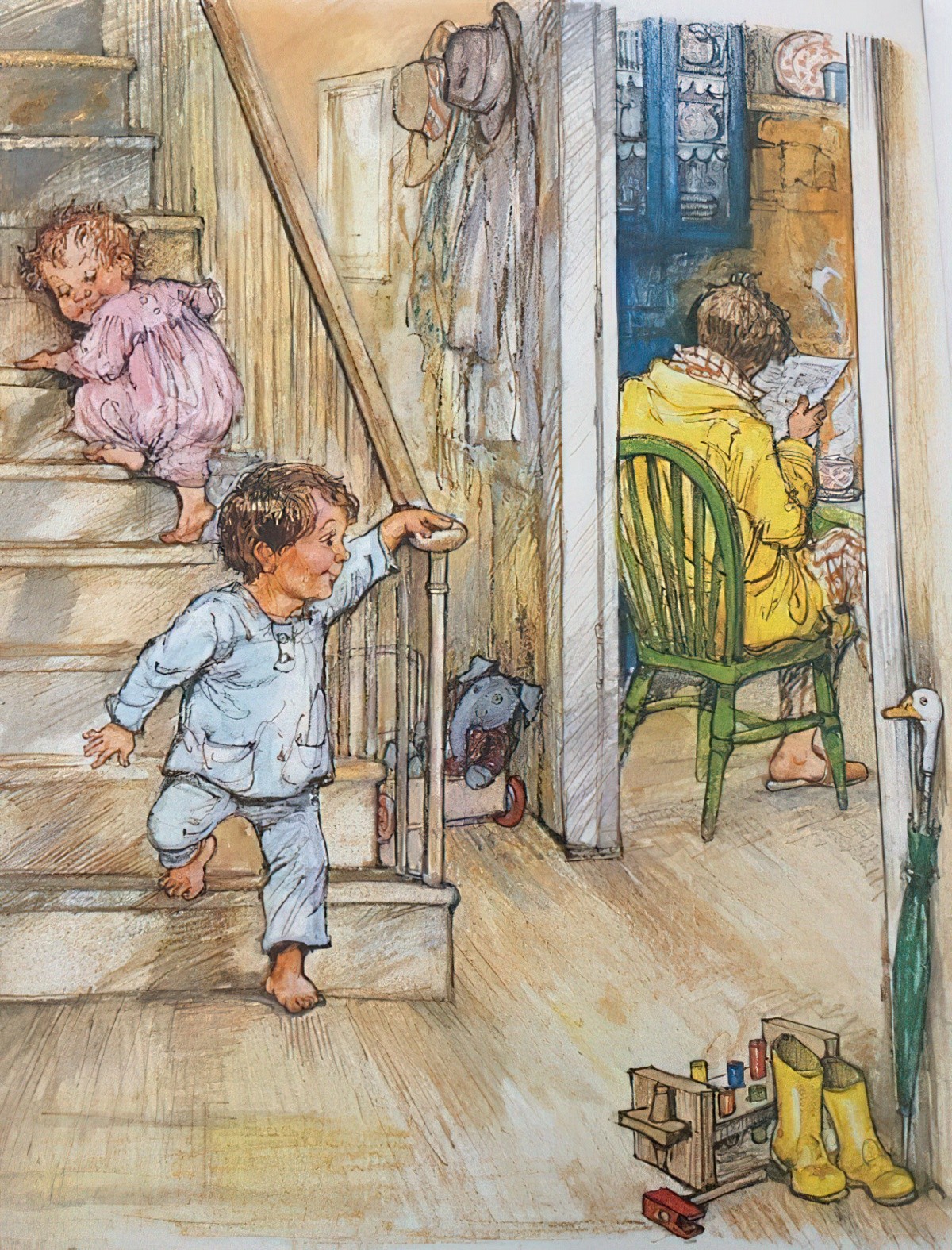

The paintings below of upper class houses go some way towards describing how a ‘hallway’ comes from the ‘hall’, which is a very large room with multiple uses.

In his book Home, Witold Rybczynski describes eighteenth century English bourgeois life, when people spent most of their time at home — a private place where one did not simply call in to the house of another — it was the done thing to leave a calling card and wait for a reply. (I believe we’ve since returned to the era of the ‘calling card’, at least here in Australia, where you don’t simply knock on the door — you send an SMS to say you might pop round.)

An invitation having been received and properly accepted, the first room which greeted a visitor to the house was the hall. Although aristocratic homes were often organized around a medieval-style centrally located hall, the hall of a middle-class house was a room adjacent to the entrance, located so that doors led from it to the main common rooms. Since it contained the main staircase, it was a large room, and, in keeping with its medieval ancestry, one that often contained coats of arms and suits of armor. Although it was no longer the main gathering room, it did serve an important function as a setting for the ceremonial arrival and departure of guests on formal occasions. Here visitors arrived, under the frosty gaze of a family retainer, to gain admittance to the house. This was the room where carolers were invited in to sing at Christmas, and where the servants gathered to be addressed by the master on important occasions.

Witold Rybczynski

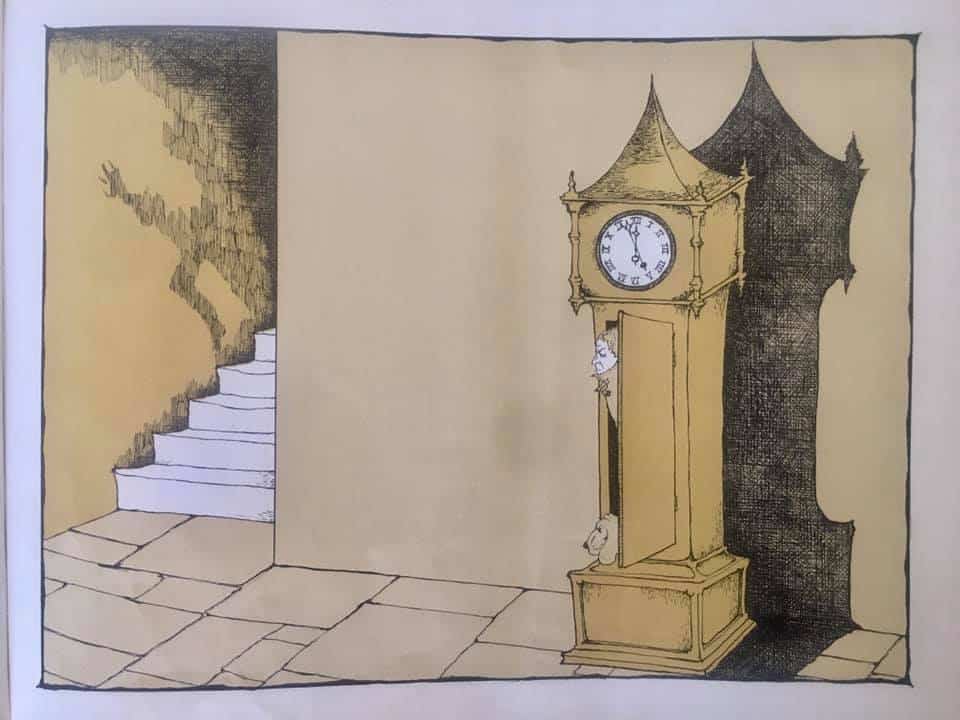

Corridors can sometimes feel as if we’re looking into a the mise en abyme effect created by two mirrors. In Anthony Browne’s illustration below, the checked tiles on the floor add an extra element of spatial horror to the sensory overload of a very long corridor with repeating doors, subtly suggesting we are stuck in this space for eternity.

Especially where stairs open into hallways and corridors, these spaces are regularly considered a place where secret converations happen. This is no doubt to do with the practical realities of landline telephones of yesteryear, where the most convenient place to anchor a phone to the wall was next to the stairs. The stairs therefore become a natural sitting place to talk for hours. It’s also possible to eavesdrop from above the landing. The hallway with stairs therefore becomes associated with eavesdropping. And because the word ‘eavesdropping’ includes the word ‘eaves’, it’s clear that the stairwell association with overheard conversation replaced an earlier trope of the spy character standing under eaves, from the other side of a wall. The ‘eaves’-dropping trope clearly dates from an era when houses were much smaller.

SEE ALSO

- Symbolism of the Dream House

- The Endless Corridor at TV Tropes

- If you’re a gamer, you’ll find plenty of corridors in the settings of games. There’s a reason for that.

Header painting: Herbert Thomas Dicksee – Memories, an Old Man Seated in a Church 1885