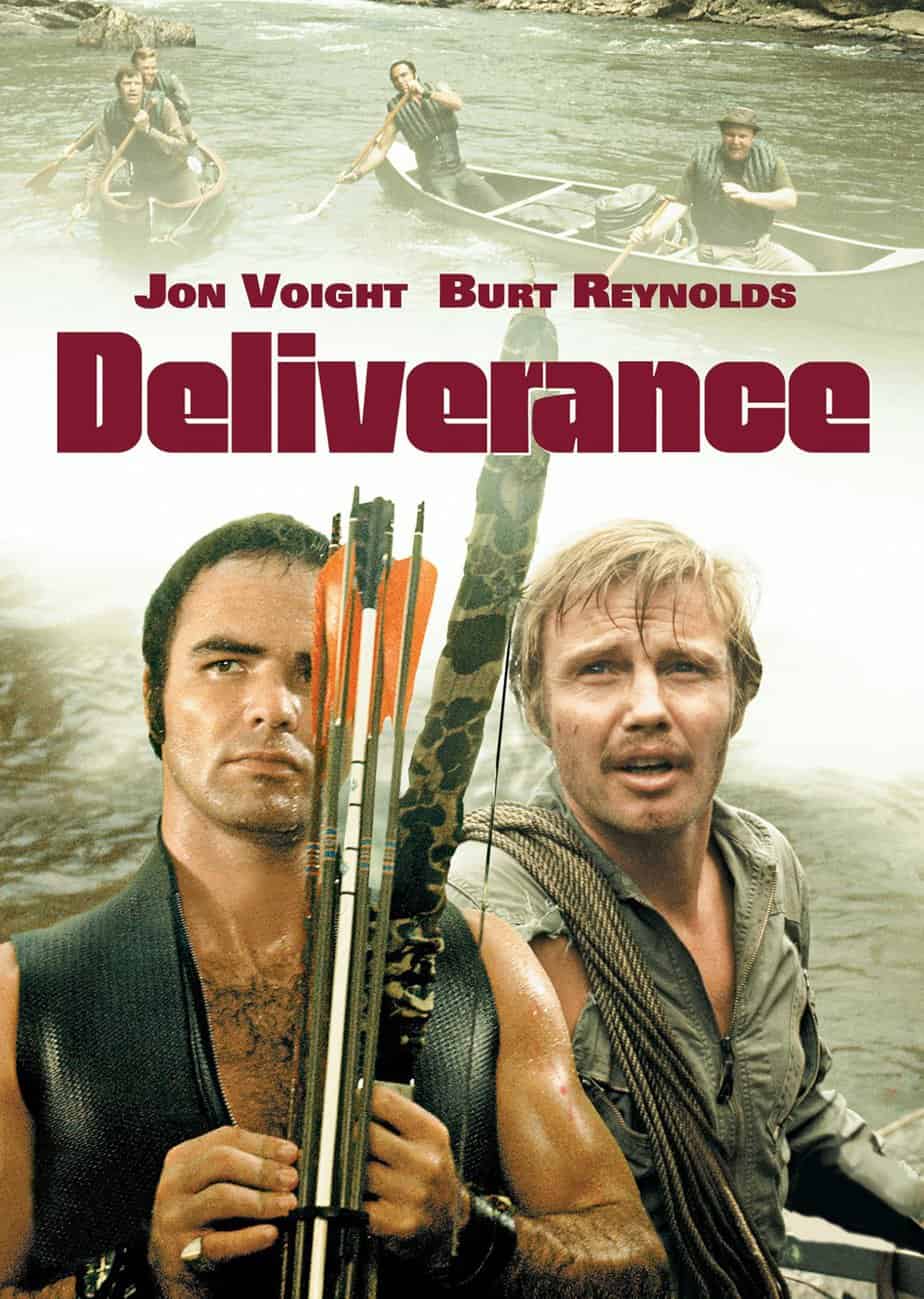

Deliverance is a 1972 movie based on the 1970 novel by James Dickey. Watch it in 2017 and it could have been made this year. The river setting, the timeless costuming, the themes and the film-making techniques have not dated. In fact, Deliverance continues to influence film to this day, including an homage in Carrie (the image of the floating hand), and the obvious influence on the 2017 film Jungle, starring Daniel Radcliffe.

THE REAL LIFE-THREATENING REALITY OF SHOOTING DELIVERANCE

Deliverance is impressive when considering this was film shot before CGI. Actors put their lives at risk on this river, and didn’t come away unscathed. When playing dead, actors were either drunk or trained themselves to hold their breath and not blink for two minutes. Jon Voight really did scale that cliff, but with a harness that had to be kept out of the shot. When the boat breaks in two, that was thanks to a complex pulley system set up under the water.

Unfortunately Burt Reynolds broke his tail bone and never fully recovered from that injury. Many years later, when Meryl Streep was filming The River Wild, she must have been thinking of this when she was almost killed during shooting.

SOUNDTRACK

The budget for Deliverance was very tight. Director John Boorman dropped the composer and went instead with the same banjo music utilised across the entire movie, functioning as a very simple soundtrack. Budget constraints led to a very pared down movie, but this simplicity is what also makes the film so good in the end.

Genre Blend Of Deliverance

In 2010 The Guardian named Deliverance as number five best action and war film of all time, which is a bit weird considering there’s no human war. (The war is man versus nature.) Deliverance is sometimes considered the first ‘eco-thriller’ which doesn’t really need further explanation — it’s a thriller with an ecological theme. Jaws and the Jurassic Park stories are other examples.

IMDb lists Deliverance as Adventure, Drama, Thriller, but there are also horror elements. The horror elements are what made Jon Voight reluctant to do the film. He read the script and had to have his arm twisted, because horror is not his thing.

Setting

Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film

If you mention Appalachia to many people, they may immediately respond with the “Deliverance” dueling banjos theme. Unfortunately, this is an example of how the region is stereotyped and misunderstood, particularly in films. In her book, Unwhite: Appalachia, Race, and Film (University of Georgia Press, 2018), Meredith McCarroll, Director of Writing and Rhetoric at Bowdoin College, describes Appalachian people as being shown as different from both white and nonwhite groups, often considered as belonging to the worst of each group. Her book discusses specific film examples that help to illustrate the negative connotation heaped upon Appalachia, and also presents where filmmakers treat them more fairly.

New Books Network

The River

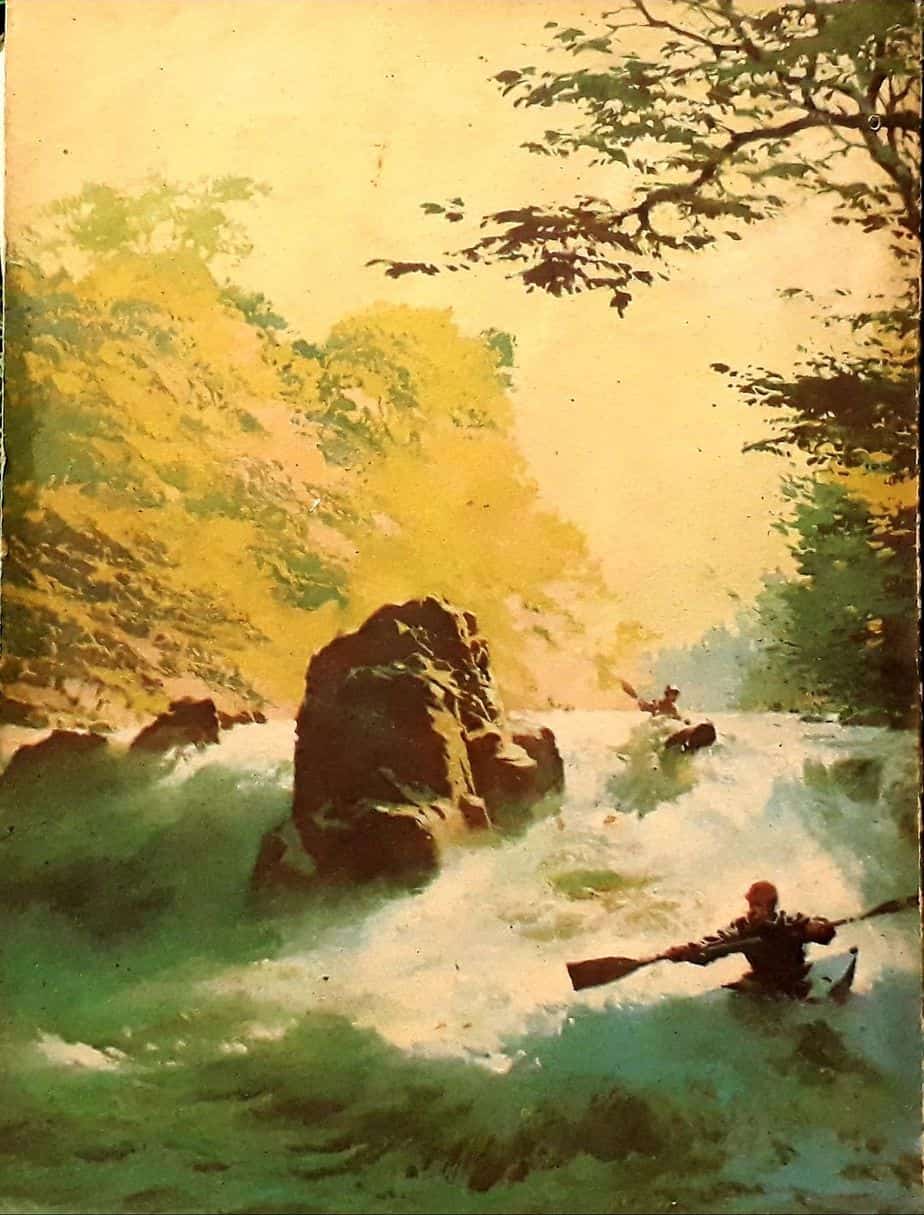

The Cahulawassee River is a fictional river and the movie was filmed on the Chattooga River.

The “Cahulawassee River” is likely a disguised reference to the Coosawattee River, which underwent development after the Army Engineers approved the building of a dam in 1959. Today, the result is Coosawattee River Resort near Ellijay and Carter’s Lake; the former dramatic rapids are no more.

(The article tells us Coosawattee translates to ‘old Creek Indian place’.

Chenocetah’s Weblog

The Chattooga River is one of the most difficult rivers to kayak — rated top level difficult. After the film came out a number of people decided to try rafting down the Chattooga and a number of them died. When asked if he felt any guilt over this, the director explains on the director’s commentary of the DVD that he actually went out of his way to make the river look dangerous and uninviting. The Chattooga is beautiful and mostly untouched at time of filming, but too beautiful for the film. In editing the film was heavily desaturated, which I had initially put down to it being an old film, but this was done deliberately at the time.

Although dangerous, on film the Chattooga doesn’t look especially dangerous. It looks calm on the surface. For the scene where the boat breaks in two, the filmmakers had to damn the river upstream, then let it go to create the right visuals. The first time they did this it trickled out and had little effect. The second time it came out much stronger than intended. The director still feels bad about that, especially since Burt Reynolds was doing his own stunts and injured his back. You can see the moment he injures his back which made it into the film, as most of this director’s film does. Burt struggled with injuries from many stunts his whole life, but in 2009 had to undergo back surgery and has been addicted to pain medication, so once you know that about the actor it’s hard to really enjoy that scene.

The symbolism of this river is a bit different from the symbolism of most rivers in stories (which tend to symbolise the flowing of time, with emphasis on irreversibility), because this river is about to be dammed. A dammed river means a stop – a premature stop – in time, a death. It makes symbolic sense that there were deaths on this river which is about to be dammed.

The irreversibility of time is also a feature of this symbolic river. “Now you tell me how a canoe can drift up river.” says the cop, emphasising there’s no going back (in time).

The Setting As Character

Back to the narrative, Boorman really liked how the leaves looked during the scene where the men argue about what to do with the body. He describes the colour as ‘acid green’, and did not remove the colour from those scenes. He used an anamorphic lens to open up space between the characters in the rape scene and following, to let the audience see more of the forest.

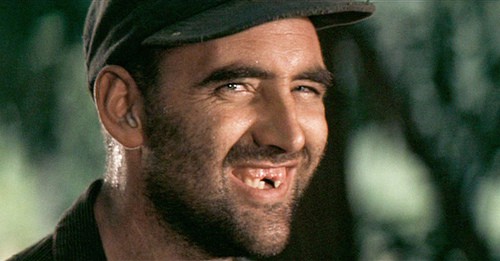

Boorman says he regarded the setting as a character in its own right. I believe Boorman means the setting in Deliverance is functioning as an unseen army opposition. In fact, the rapist and his toothless sidekick are not treated as characters.

Boorman says on the commentary that he regards these two as malevolent under spirits of the forest representing the people of Atlanta, who are about to desecrate the river to make a dam. To Boorman’s mind, ‘character’ does not correlate with ‘human’.

The opening scenes are brighter, shot in full daylight, but for the river scenes he aimed to shoot on overcast days as much as possible. Because this is the Appalachian Mountains, a lot of the days are foggy, in fact.

After the men emerge from the river, the editing style changes. The river has been nothing but hard cuts, but now Boorman makes use of dissolves, to give the emergence a dreamlike quality. These men have re-emerged into civilisation and can’t quite believe it. They’ve been through such an emotional journey the real world looks quite different. At the end we get to see the river beginning to be flooded, and communities are sinking under this water, now placid and tamed. Ed and Bobby row past the dam where the water is rising. There’s something sacrilegious about killing a river, and something raw and crude about the dam.

Though this isn’t in the novel, Boorman has his own symbolism attached to the river/lake (which he considers one and the same). Rivers are always symbolic in story and can signify many different things, but to Boorman the body of water represents the subconscious. At the end, when the bloated dead man’s hand emerges from the water it dissolves into the post-traumatic dream of Drew. (That’s the image that you’ll find as homage in the first film adaptation of Carrie, made four years after Deliverance.) TV Tropes call this The Raised Hand Of Survival. It’s related to the horror trope in which a dead monster never really dies, mechanically coming back from the grave to continue to wreak havoc.

Appalachia

When the writer visited this part of America and required help from the locals, they were the friendliest people you could ever hope to encounter. So what did he do? His sadistic writer’s brain kicked in and he wondered what would’ve happened on his trip if the locals had not been friendly.

So is this really an Appalachian story?

The native Appalachian people filmed are descendants of people who were part Native American, part white, and therefore ostracised from both communities. They turned in on themselves and this has caused problematic lack of genetic diversity. When Lewis peers into a window and sees a girl with multiple severe disabilities sitting next to her grandmother who is sewing, this is not staged. This is a real pair of Appalachians doing what they do, and the camera peered in the window. The old woman and the girl do not get acting credits. (I hope they at least got paid, and gave permission.)

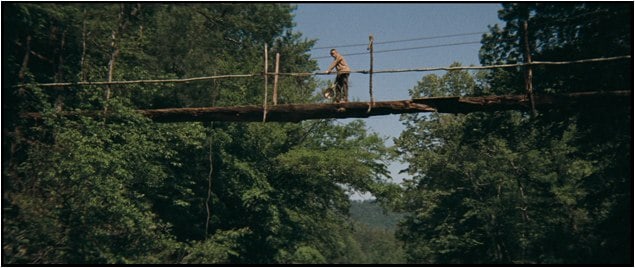

The boy who plays the banjo does not have a mental disability, but because he looks like he does, he is treated as disabled by the rest of his community. By the director’s description this actor is perfectly bright, but could not in fact play the banjo. They found another child actor who could play the banjo, and the hand that comes up behind the boy belongs to a kid sitting behind him, doing the frets. The first few times I saw this film I thought the boy was supposed to be blind, but no. When the boy looks down at the men from the bridge, his thoughts are ambiguous, but because he is shown to be a kind of savant, it’s like he knows something about the river that the men don’t.

If you’re from rural America, however, particularly from Appalachia, chances are you still hate Deliverance for the powerfully negative effect it has had (and still has) on outsiders’ perceptions of this region, presenting it as all hookworm and incest, buckteeth and bluegrass. “Squeal like a piggy, boy!” is a phrase that can still get you beaten up south of the Mason-Dixon line.

The Guardian

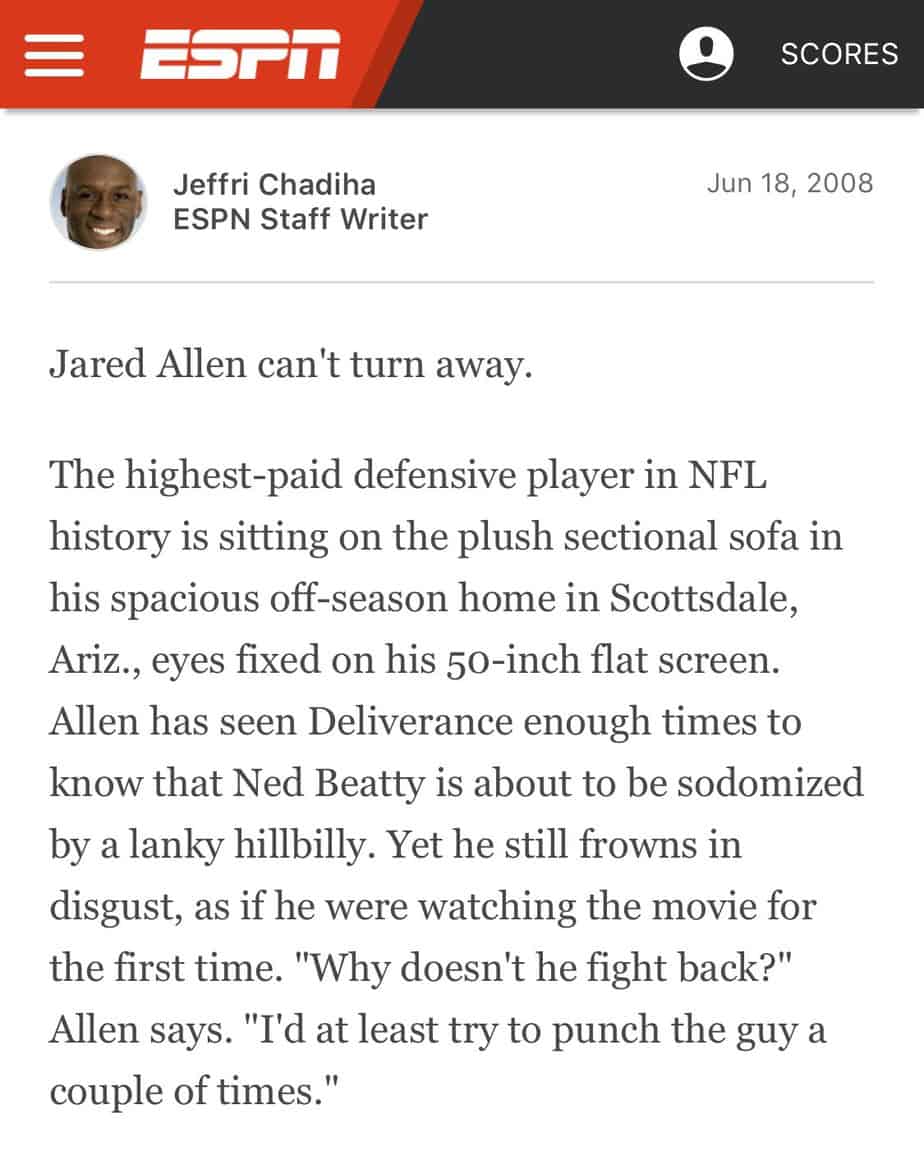

The actor who played Bobby spent the rest of his life enduring people yelling at him: ‘Squeal like a pig!’ Acting the part of a rape victim led to its own measure of PTSD. He felt as if he were really raped, and the feeling never left him. These days, ethical directors employ intimacy co-ordinators on set.

Boorman has had people tell him they walked out during that rape scene and one man told him he never again set foot in a cinema.

I do wonder if the men who failed to sit through the rape scene in Deliverance were equally repelled by the much larger number of fictionalised scenes in which women are raped as part of a male narrative arc. Would that man have walked out of Thelma and Louise, for instance? Did the terrible shower scene from Psycho disturb him, or titillate him? That is another question worth asking, because Deliverance is one of the few films in which the rape of a man is used as another man’s character arc. Usually, by far and away most often, it is the rape of a woman that is used instead. I suspect a lot of men are unable to put themselves in the position of a rape victim unless that victim is also male.

THE GEORGIA ACCENT

The director said that the Georgia accent is so extreme that anyone who speaks in it is halfway there as an actor. (Non-actors were used as extras in this film.)

Time In Cinematic History

The rape scene was new for 1972 audiences and has not been oft repeated. The violence was also new. The killing of the rapist was necessary to depict because this is the scene that brought on the moral decision. But when the film reached the censor’s office they ran into trouble. The censor at the time didn’t mind scenes where a man was shot and dropped out of frame and that was it, but didn’t want an audience to deal with a lengthy death. It takes a while for the rapist to die from the arrow wound. (The actor had to train himself to not blink and hold his breath for two minutes, which is how he convincingly looked like a dying man.)

The contradiction between the censor and the filmmaker: The censor believes that by lingering on a death the audience will either be shocked out of the theatre or learn to revel in it. The filmmaker believes that unless it’s a lengthy and therefore realistic arrow death, the audience will fail to take the gravity of the situation seriously. In the end, both censor and filmmaker have the same exact fear: That audiences will not take the death seriously.

The expression ‘squeal like a pig’ came about because the studio demanded they shoot alternative language for television so they had to find alternatives. So they all tried to think on the spot – everyone hates doing TV alternatives. It took the place of a more powerful phrase. But it was so good the director decided to keep it in the film version.

Time In History

When Ed returns home to his wife and wakes up plagued by post-traumatic dreams, it is clear how similar this experience is to that of a war veteran. Fun fact: The author himself was a fantasist, both off and on the page. He used to tell people he was a veteran of the Korean war, but he wasn’t. However, he might have been drawn to war stories. He would certainly have known a lot of men who had been to war, and perhaps by writing this novel he purged himself of some war fantasies. If he never went to war it makes sense that he himself might feel some deep, masculine desire to test himself in the wild against a formidable force. A lot of the movie-going audience lived through wars. Deliverance is a war story in theme rather than setting.

By the way, Dickey also told every actor on set that everything that happened in the film happened to him personally. But when Boorman saw him get into a kayak for the first time and capsize immediately, he realised nothing in the book had happened to him personally.

Characters In Deliverance

Who is this story about? Men. This story is about basic masculine urges and how they are civilised and suppressed by modern life. Burt wanted to kill someone. Men have an underlying need to express these deeper urges, which is why there’s the madness of war, why war is so exciting to many men (and also sport).

Deliverance is an interesting case study when it comes to character function. The logline tells us the main character is probably Lewis:

Intent on seeing the Cahulawassee River before it’s turned into one huge lake, outdoor fanatic Lewis Medlock takes his friends on a river-rafting trip they’ll never forget into the dangerous American back-country.

But this is a story about an ensemble of men. These men are so different from each other you wonder how they’d be friends in real life. In fact they’re not — Lewis doesn’t know a couple of the guys before this trip. Whenever you wonder how fictional characters would even be friends, it’s probably that each character stands in for a different facet of personality in The Everyman. (Or Everywoman, or Everychild). Deliverance is specifically a film about masculinity, and the various ways of being a man in the early 1970s. Men have a wild side, a conservative side, an underdog side, a family man side.

Lewis

‘Tarzan’. He wears a sawn off rubber jacket exposing his biceps. Costuming was all the more important since we didn’t see these characters in Atlanta.

Ed

Ed is a family man who has known Lewis from way back (we’re not told how). Ed is an advertising executive, as the author was himself. This is the character Dickey most heavily associates with. Ed is not a natural macho man, but must take over once Lewis breaks his leg. He contrasts with Burt in his grey sweater.

Bobby

Bobby is the chubby insurance salesman who ‘is highly regarded in his field’, according to the kind-hearted Ed, anyway. Bobby is an archetype — the aggressive yet cowardly side of a man. Bobby is your modern gamer guy who is terrible at games but picks on girl avatars. He is pretty scathing about the hillbillies and loudly announces his disdain for the rubbish in front of the hillbillies themselves, commenting on all the rubbish, and they must have reached the end of the world, where all the rubbish ends up. He wears a comical pork pie hat.

Drew

We don’t even know this guy is a family man until the improvised funeral. On a continuum of morality, this guy is the most law-abiding and honest. He is also sacrificed.

Matt Bird, in Secrets of Story, writes that even when a narrative is about a group of characters, the audience warms to one in particular. This isn’t necessarily ‘the good guy’. Who did you warm to?

Lewis

is an interesting character, probably on the sociopathic spectrum, full of contradictions. He tells Bobby not to judge the hillbillies based on their looks, while all the while judging Bobby for being chubby, thinking him incapable of the river journey. He’s basically an asshole who seems to take delight in putting his male friends to the test, thinking he’ll come up trumps. His magnetism is no doubt partly down to Burt Reynolds’ star quality (this was the film that launched him). Boorman admits that Reynold’s overacted at times, but persuaded himself the cuts were okay because that’s who Lewis was. Lewis is not an empathetic character, but I do sense his need to get into the jungle and really test himself to his limits. He’s an adrenaline junkie. “Who does he think he is, Tarzan or something?” asks one of the other guys as Lewis goes off at night to investigate a noise. We are given enough information to make our minds up rapidly about Lewis. This guy is an archetype.

Ed

Ed is the character who has the character arc, transforming from someone interested in nature but cowed by it, to someone who faces a life and death struggle, and pulls through, transformed (though tragically).

Bobby

Bobby is an archetype, and he too is sacrificed in a way (after the rape scene). Bobby is not an empathetic character even though Lewis calls him ‘Chubby’, mostly because when the underdog picks on even weaker characters we can’t possibly feel sorry for the underdog. An audience has no sympathy for that. Also, he sells insurance. Presumably, Bobby does just fine back home in Atlanta. Bobby is a boy’s name – his chubbiness is like early boyhood. He has no character arc in this story. He doesn’t grow — he shrinks.

Drew

Drew is Good, almost to the point of being a Mary-Sue character, engaging the boy in the banjo-guitar duet, treating him as an equal for that moment, always the voice of reason, emotionally literate. Yet he remains in the background. We see less of him than of Lewis and Ed. He exists mainly to be the voice of reason in the dialectic about turning themselves in.

Each of these characters represents part of the author himself. Those who knew him could see this clearly. Funnily enough, the guy behind The Muppets says the same thing of himself:

Yes, I identified most with Grover and Fozzie, but there are bits of me in all of my characters. Me being boring is Bert, me pure is Grover, me obsessed is Cookie, me neurotic is Piggy, me insecure is Fozie, me uptight is Sam, me crazed is Animal. I’m a bit like each of them. And so are you.

(Noted with interest which of these traits Oz associated with femininity.)

Frank Oz

Backstory

From a storytelling perspective it’s interesting that Boorman chopped the first third of the novel right out. In Dickey’s novel the first third is about these guys’ regular lives in Atlanta. Boorman found this tedious, ploughing through the characters interacting with their wives and children and at their jobs. He knew that the audience would understand these guys with very little information, so he plunged us right into the wilderness with them. By the time the gas station scene has ended we know who they are, and if we’re still in any doubt, watching Lewis speed down that unfamiliar dirt road while Ed sits terrified in shotgun cements any ambiguity. This was Boorman treating the audience with respect, and marked a more modern way of storytelling. There’s a lesson in there somewhere about backstory. The reader doesn’t need nearly as much as the writer thinks we do.

In sum, this is Ed’s story. Ed is most often the focalising/viewpoint character.

- We watch the hillbillies from Ed’s point of view, standing by as Ed plays guitar and Bobby makes fun of the attendant.

- When Ed is scared of Lewis driving, we’re scared for them.

- Ed is looking on as Bobby is raped

- Ed goes missing after the small waterfall. We close in on Ed’s face.

- We see through Ed’s eyes when the cops turn up — they’re talking to Bobby already.

Story Structure Of Deliverance

SHORTCOMING

It’s up to the audience to work out for ourselves why these men are on the river. The gas station attendant challenges the men, “Why do you want to do that for?” The audience might be wondering that too. But with this being a macho story, we understand by the end of the film that these men — Ed included — have a deep-seated psychological need to remove themselves from the safety of Atlanta and transport themselves to the wild where their manliness can be truly tested. By leaving out the backstory Boorman trusted his audience to get this intuitively.

DESIRE

He wants to kayak down the river with his long-term friend Lewis and two newer buddies from Atlanta then make it home safely to his wife and son.

He wants to prove himself capable as a man in the wild. At least, he doesn’t want to be shown up by Tarzan Lewis. We see this below-the-conscious desire when he wanders into the woods to try and shoot the deer. Why does he want to shoot it? Not for the meat, surely.

Early in the film Ed says something along the lines of, “It doesn’t matter what’s happening in the world — no one will find us out here.” The men have been ‘delivered’ from the real world, transported into the wilderness. Later, most of them will be ‘delivered’ once again into civilisation. This speaks to Ed’s desire to get away from civilisation, but also foreshadows trouble to come.

OPPONENT

A very typical character web: The big, bad, inhuman opponent (nature, the dangerous river, the characters who are part of the landscape) is pitted against a small group of individuals who in turn are united against this big bad monster baddie but also function as opponents to each other owing to their day-to-day butting of heads. At first Lewis looks like he could be a psychopathic river buddy but he is soon taught a lesson and the setting itself becomes Ed’s main opponent.

On that point, the downfall of Lewis is satisfying because he’s such a dick-waving macho man, full of talk about needing to respect the river then failing to respect it himself, that it feels like karma and revenge when he breaks his leg and suffers immense pain because of it, needing to be rescued by his beta-male friends. I do believe this is a bit of wish-fulfilment the writer is exploiting in us with Lewis.

“You don’t beat it. You don’t beat this river.”

Lewis

PLAN

Lewis challenges Ed about the strength of his desires near the beginning of their trip. “Why do you come along with me on these trips, Ed?” he asks. Ed admits he doesn’t rightly know. Ed is basically along for the ride, on a plan made by Lewis. When you’re writing a main character whose character attribute is ‘passive’ or ‘laid back’ it’s a good trick to give them a sidekick (who may initially look like the main character) with go-getter tendencies. This sidekick will start the story in motion. That’s Lewis, of course — the ‘protagonist’ in the original Greek meaning of the term.

Ed’s plan is to go along with Lewis for a fun time, see what happens.

BIG STRUGGLE

Deliverance is a mythic journey, so the men encounter a series of battles, culminating in intensity. (Unless the battles culminate a journey can feel too episodic).

- They struggle against the current, at first in small current, then in very large.

- Ed battles the deer (and loses his nerve). As he works his way through the forest searching he is now alone, away from the others. The sense of four people together has gone. We are all ultimately alone in death and this foreshadows that moment for him.

- They hear a noise which may or may not be human (see what the writer did there?) and fail to locate the source

- They low-key argue with each other along the way, establishing a pecking order

- The men’s big battle with each other is the dialectical scene about what to do after Lewis shoots an arrow through the rapist. Lewis comes out on top, and Drew loses big time. When he falls into the river soon after, it’s deliberately ambiguous — did he throw himself into the water in despair or was he really shot? In the previous scene, when Drew starts to dig the grave, the digging becomes neurotic and it’s almost like he’s digging his own grave. They’re descending into a kind of primitive world when they bury the rapist. There’s no priest or ritual. Nor is there any priest when Ed and Bobby are required to perform an impromptu funeral for Drew.

- Ed’s struggle culminates with the murder of the Toothless Man (or is he?) and there’s a great visual as he comes face to face with his victim under the water.

- There’s another struggle between Ed and Bobby about what they’re going to tell the police. The two men are wearing the same shirts. They’re forever psychologically bound together because of the transformative experience they just went through.

Through these struggles, the closeness of the men is being sundered. Sometimes a series of big struggles brings a family closer together (e.g. Little Miss Sunshine), but in this story the characters are torn apart.

ANAGNORISIS

Dickey himself explains the anagnorisis had by Ed:

“I think only one thing; that men…settle for too little in their lives. And this chance encounter in the river was for…Ed Gentry, some kind of opening to a dark place he would never know was there…John Berryman [the poet] once said that a man can live his whole life in this country without knowing if he is a coward or not. I think it is necessary for him to know.”

James Dickey, on Deliverance

At what point do we see this self revelation happen on screen? We don’t see it happen immediately in some kind of rapid, epiphanic moment. This is why the denouement is important to this story.

When he shoots the man we know the macho part of his character arc is complete, because it started the moment we saw him unable to shoot that deer.

By the way, it’s accidentally unclear to much of the audience exactly what happens when Ed shoots the arrow at the toothless man. He shoots him in the back, and then immediately rolls over onto another of his arrows by accident. The director didn’t mean this to be at all ambiguous, but says that’s the best he could do in hindsight. It doesn’t help that we don’t see the enemy has been shot until he turns around.

When Drew throws himself into the river (or is shot), this demonstrates a very conservative view on truth and lying — by blunting the truth, this had a corrupting effect on the men. The underlying assumption is that lies can never really be buried — the truth either finds its way out, or haunts you forever. A non-conservative message would be the inverse — that lies are sometimes for the best, and let’s all move happily along with our lives.

NEW SITUATION

Boorman had to fight for the scenes that came after the men rowing into Aintry, with the rusty old cars on the side of the bank. By the by, Boorman describes these cars as ‘ironic‘. The men have earlier disparaged these rusty old cars as as symbols of non-civilisation — now they’re using them as evidence of civilisation. Their attitudes have changed in just a couple of days.

Why did Boorman fight to keep these scenes? Not because the audience couldn’t guess about how their lives were going to look now — but because we needed to see their slow anagnorises play out. Ed starts crying in the Aintry restaurant, but the kindly people there deflect and a woman starts talking about a comically large pumpkin. This shows his faith in humanity will slowly be restored.

We need to know if Lewis lives or dies — when we send him off he may or may not lose a leg, turning him into how many war veterans looked in those days. Stories such as Lonesome Dove end with survival but loss of limb — a victory is a pyrrhic victory if you don’t come out intact.

For Ed the point is very much the self-knowledge he gleans after he is forcibly set free.

John Kenneth Muir

The brothers they paid to deliver their cars came through. Ed can’t really believe the cars are there waiting for him.

The matter of the dead man is tied up briefly. It was Deputy Queen’s brother in law they shot – “He’ll come in drunk, probably.”

When Bobby and Ed say goodbye Bobby says, “I don’t think I’ll see you for a while.” I suspect those two never see each other ever again. Sometimes when a friend becomes associated with a negative experience, compartmentalisation means the friend has to go, especially if it’s a new friend.

Ed will go to visit the widow and family and do what he can for them, because we believe he’s a man of his word, not because we need to see it play out on screen. We do see him go home to Atlanta, hug his own wife and play with his young son.

Ed is a city man but connected to nature, yearning to be among it. But does he have what it takes to really survive in nature? Yes, it turns out he does. He has physically survived, but by turning into Lewis he lost a part of himself.

We see the little white church several times. This is a church rescued from drowning, later towed away. There’s a sense of having come back to civilisation but there’s this church is hanging over them, accusing them of this crime they’ve committed.