Daniel Craig says “why should a woman play James Bond when there should be a part just as good as James Bond, but for a woman?”

“There should simply be better parts for women and actors of colour.”

DiscussingFilm (@DiscussingFilm) September 21, 2021

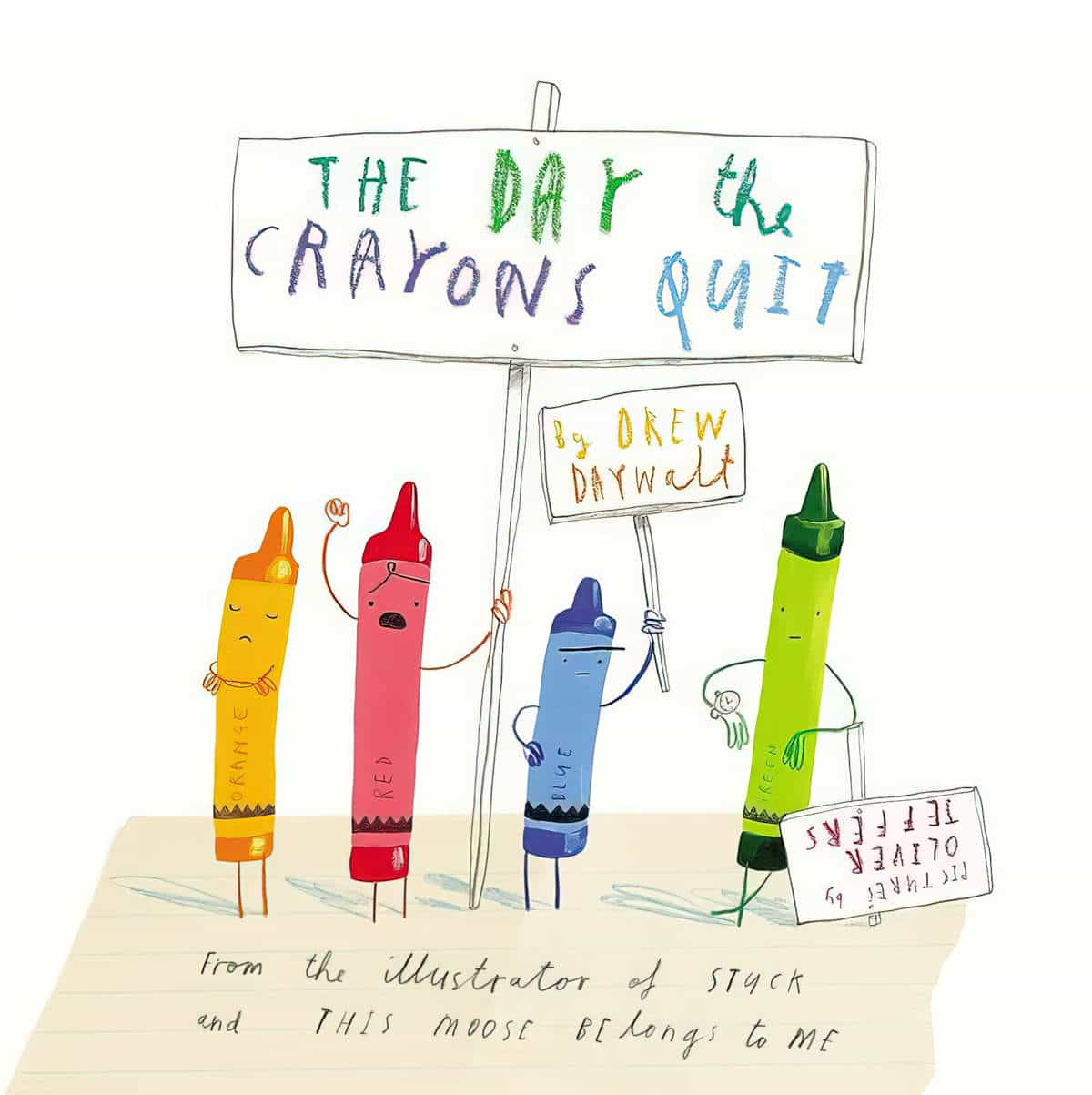

The Day The Crayons Quit is a bestseller made by two picture book superstars, so I’d like to use it as an example of something which bothers me a lot in children’s literature and film: Gender inversion that ironically supports the status quo.

On the surface, The Day The Crayons Quit contains a message for young artists: Use all the colours in your crayon box. Use them in original ways. (‘Think Outside The Crayon Box’.) And the gender message for boy readers: If you’re a boy, don’t be afraid to use the pink crayon. There is also another message, more implicit than that: Pink is for girls, and girls are one big blob of similar people who ‘colour within the lines’.

Pinkification

This is of course a response to the pinkification of toys and games that’s been happening over the past 10-20 years.

- Do Gendered Toys And Playtime Have Their Place Or Is It All For Profit? from The Mary Sue.

- Stereotyping Childhood from Don’t Conform Transform. Why does the pink and blue division of toys matter? See also: I’m Dreaming Of A Non Pink and Blue Christmas from the same blog.

- Beauty And The New Lego Line For Girls from The Society Pages (See also: Retro Lego Catalogue Praises Little Girls’ Imagination from The Mary Sue. And if you’re wondering what the new Lego for Girls looks like, you can see it at Ms Blog.) Here are a couple of retro Lego ads, and as far as I’m concerned, they should still look pretty much like that.

- Lego For Girls Already Exists. It’s Called Lego from Mommyish, and here’s more commentary on the superfluousness of the new Lego line, which is discussed amid a handy explanation of Stereotype Threat from Don’t Conform Transform. (Girly Lego Sucks, But It’s Selling Like Hotcakes — an update from Jezebel.) And if anyone here is still wondering what the problem is, Peggy Orenstein tells Mommyish Why Those Girly Legos Should Give Parents Pause.

- Gender Typed Toys: What The Research Says from naeyc

- On Vanity And Princess Culture from Blue Milk, talking about dolls and other faux-harmless toys for girls

- Pink Or Blue: Defining Gender Neutral Parenting – Baby Storm’s parents have not revealed Storm’s gender.

- Toy Ads And Learning Gender from Feminist Frequency (a video)

- But just because it’s not pink, doesn’t mean it might as well be.

- Monica Dux conducted an experiment: ‘Walking my baby up and down a busy shopping strip. She was dressed in a lime-green hoodie and pink pants but before I set out I covered her pants with a grey blanket. The immediate assumption from all those who cooed at my infant was that she was a boy.’ The rest of the story is here.

- Embracing Girly: On Letting Girls Be Who They Are from Don’t Conform Transform: ‘There’s nothing wrong with a child choosing any or all of those things or loving them, but there is something wrong with media and marketers providing only one vision of what a girl can like and who she can be.‘

- Feminizing The Masculine, a Pinterest collection which ends up being a visual guide to how pink is used to market to adult women as well as to girls.

- Are Gender Neutral Spaces Actually Doing Anything?, from Inequality by (Interior) Design

- Dame Jacqueline Wilson dares her publishers to not put a pink cover on just one of her books, to prove they would still sell, from The Telegraph

- Default: male from Feminist Linguist

The Difficulties Faced by Authors/Illustrators In Conveying This Message

Back to problems in The Day The Crayons Quit.

First I’ll quote Jennie Yabroff who wrote in The Washington Post:

Even children’s books that seem radical in other ways reinforce a male-dominated universe. The current bestsellers “The Day the Crayons Quit” and “The Day the Crayons Came Home” have been praised as parables of inclusion and celebrations of diversity. One bookseller I spoke with even described the rebelling crayons as a metaphor for the Occupy movement. Yet not a single crayon is identified with a female pronoun. Just about everything and everyone in the books — from five of the crayons to a paper clip to a sock to Pablo Picasso to the crayons’ owner, Duncan, to his father to his little brother — is male, or not assigned a gender. The exceptions are a female teacher and Duncan’s little sister, who uses the otherwise under-employed pink crayon. To color in a picture of a princess. And is praised for staying in the lines.

Jennie Yabroff

Anita Sarkeesian has explained in detail our culture’s tendency to create a cast of male characters, each with differing personalities, then create a new ‘female’ version. Her defining characteristic is ‘femaleness’. The audience knows that this is the girl because the creators have slapped a bow on her head, put her in heels and a dress, given her eyelashes or marked her with pink.

This doesn’t just happen in video games — it happens on TV shows designed for children, in computer software used in schools, in advertising, in toys, and of course in mass market picture books.

Since readers of The Day The Crayons Quit have been acculturated within a system which pinkifies everything associated with girls, it should have been clear to this book’s creators — who presumably understand this tendency in children precisely so they can subvert it — that without gender pronouns, or clothes, or human names, the crayons are all default males.

It should also have been clear to any creators properly schooled up in gender politics that getting the male hero to pass on a message praising his little sister for ‘staying within the lines’ is just the sort of sexist bullsh!t that turns primary school aged girls into what I’ve heard teachers refer to as ‘colourer-inners’ by the time they hit high school. No, that’s not a grammatically sensible phrase, but an English teacher I once knew used it to refer to her female students who, instead of doing the research and the thinking required before writing any essay, would spend 90 per cent of their allocated time creating an ornamental page border, choosing which shade of paper to print on, then hum and ha over 7 different system fonts without doing any actual work. Having later taught at a girls’ high school myself, I became so exasperated with this tendency that I banned any modification to the Word template at the start of each lesson, otherwise 20 minutes would be wasted on choosing fonts and borders rather than on the thinking part of essay work.

Who could blame these girls though, after having been told their entire lives so far that looking pretty and creating prettiness was the most important thing they should do?

Drew Daywalt’s picture book hardly blows that bullsh!t apart.

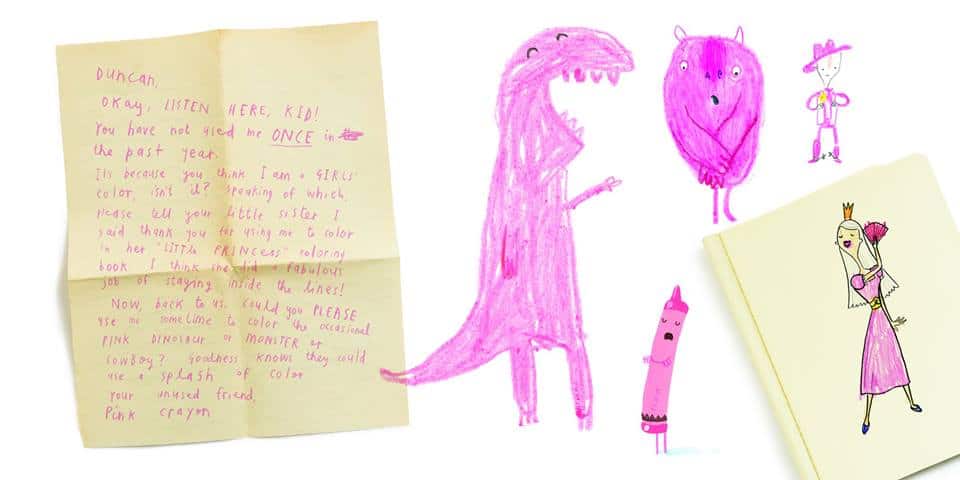

I’m most disturbed by the bit that says:

Okay, listen here, kid! You have not used me ONCE in the past year. It’s because you think I am a GIRLS’ colour, isn’t it?

The Day the Crayons Quit

I’m reminded here of all those picture books for toddlers which are designed to teach children not to be afraid of monsters. The book will then offer up a detailed picture of just exactly what a monster looks like (green and scaly or warm and fluffy) and where it lives (under the bed, behind the curtains). My own toddler was never scared of monsters until they encountered monsters in other people’s stories, and those first stories happened to be picture books, naturally.

When kids of all genders are told that this generic ‘kid’, Duncan, is not using the pink because he is a boy, there is nothing whatsoever within the text or the pictures to say:

AND WHAT’S WRONG WITH BEING A GIRL, ANYWAY?

The message is not: Femme phobia is stupid because even though pink is ‘for girls’ girls are just a-okay. No, the message is: You can use the pink crayon even though it’s an icky girl colour. (So long as you use it to make a dinosaur, not a princess.)

How Might The Crayon Book Be Better?

- The crayons probably do need to be overtly gendered, with 50/50 male/female. The pink crayon could have even been a boy, to really hammer home the ‘pink is for everyone’ message. I’m a bit icky still about all this because in a perfect world these crayons could remain completely ungendered. Also, the pink crayon is not actually marked as female in any other way apart from being pink. Still, if the creators didn’t know that was going to happen, they are surprisingly naïve.

- Don’t praise girls for colouring within the lines while offering up an example of creative freeform drawing in boys.

- Show that Duncan has coloured in the princess rather than creating a dinosaur with the pink. Maybe have the little sister be the one drawing the pink dinosaur.

- Either get rid of the bit that preaches about pink being related to girls (it should be obvious from the illustrations anyway, for children who already ‘get the cultural message’), or else append with something that challenges the inherent femme phobia.

The first part of the message works i.e. ‘Be creative and original with colour’. But with something as complex as gendered messages, unfortunately inversion does not equal subversion.

This picture book fails in its gender message. In fact, it makes the whole thing worse.

And the peach thing is a bit problematic, too, as noted by a Goodreads reviewer:

In regards to the “naked crayon” (peach) mentioned by other readers, I believe this refers to Duncan removing the crayon’s wrapper and not the author’s inadvertent implication that peach is the only color equivalent to skin tone. Even so, as others have noted, the illustrations would be improved by diversifying the figures in the book (they’re all colored with peach crayon although brown and beige crayons are referenced), especially since one of the book’s lessons is to experience color in various ways.

Goodreads

This issue is far bigger than crayon characters in a picture book, of course:

FEMME PHOBIA AND CHAPTER BOOKS

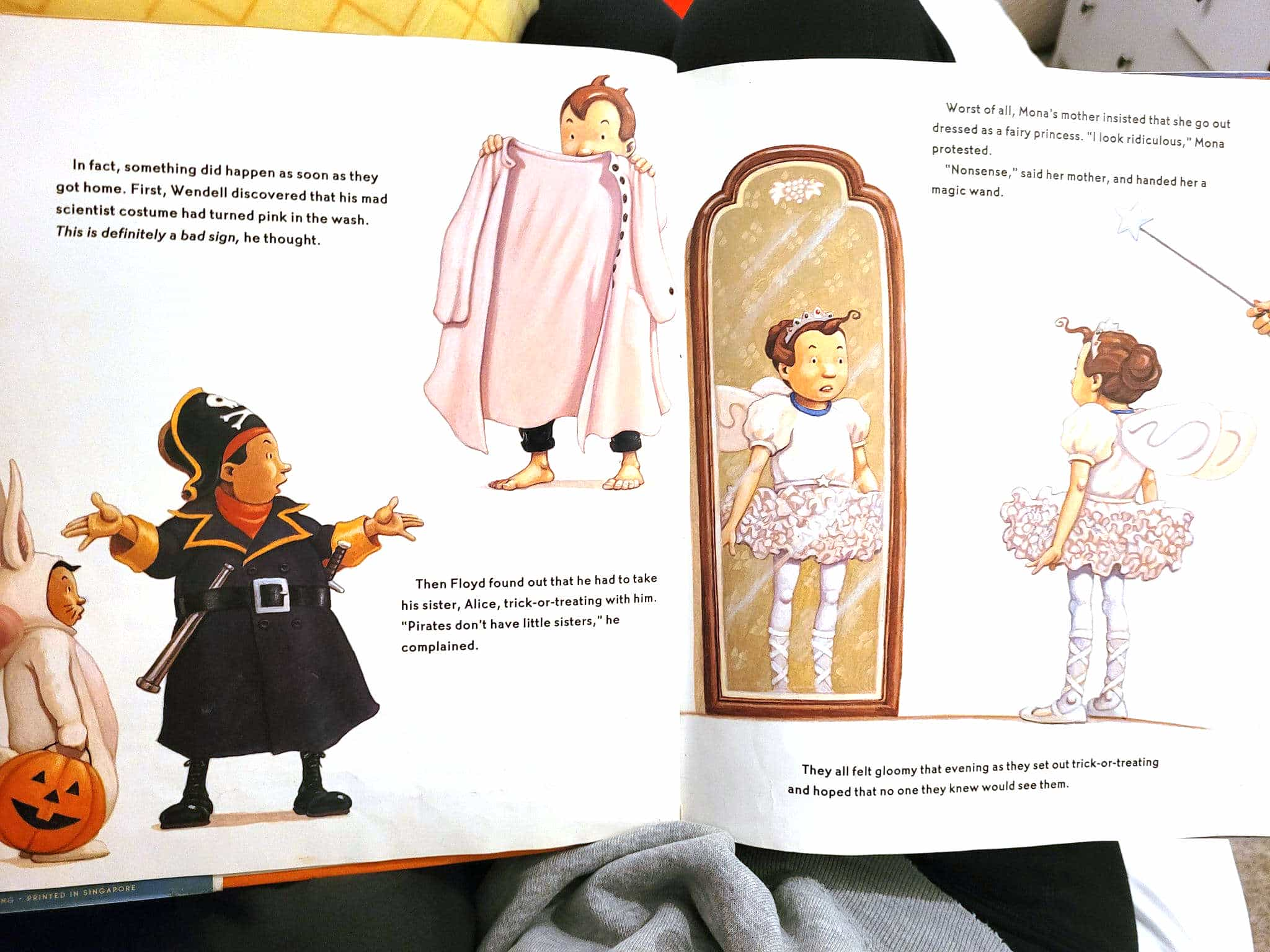

More than picture books, I suspect the chapter book is the most problematic category of children’s literature when it comes to femme phobia. No surprise, this is when children are at their most overtly gender binary and segregationist.

In chapter books you’ll find:

- Plenty of “strong female characters” who do boys things better than boys but who also despise girl things.

- Desperate housewives doing the main job of caregiving while the fun father is present but absent (or useless).

- Archetype opponents, especially pretty, well-dressed little hard-working girls who at some point will be punished by humiliation, by having their pretty dress ripped to shreds, or who find themselves soaking wet.

- Boy/girl rivalry based entirely on hating other genders (Is opposite-gender ick really a natural part of childhood or do we teach it to them?)

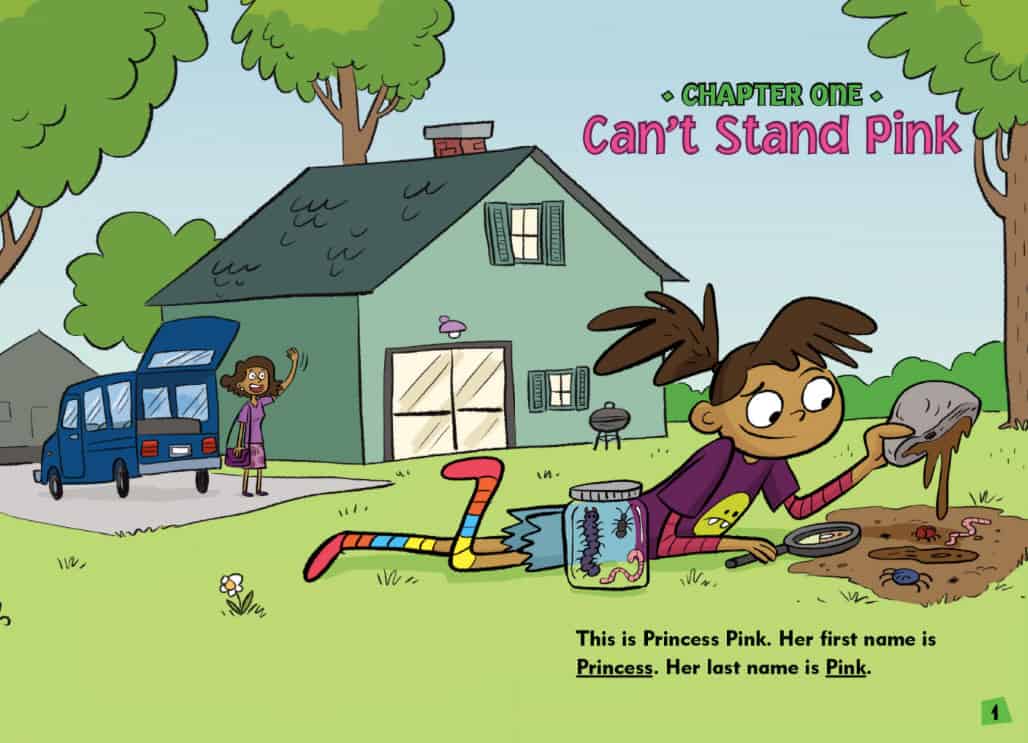

Let’s take a look at Princess Pink by Noah Z. Jones. The ‘strong girl character’ is currently in fashion. This story is read, is popular and still in print.

Princess Pink does not like fairies. She does not like princesses. And she REALLY does not like the color pink.

Princess pink does like dirty sneakers, giant bugs, mud puddles, monster trucks, and cheesy pizza.

Moldylocks and the Three Beards

Princess does not like princesses or ballerinas. And she REALLY does not like the color pink. Princess does like skateboarding and doing karate. And she REALLY likes drawing cartoons.

Jack and the Snackstalk

Princess does not like princesses or ballerinas. And she REALLY does not like the color pink. Princess likes running and jumping and yelling at the top of her lungs. And she REALLy likes karate.

The Three Little Pugs

It turns out that her brothers also like karate but she is the karate champ.

Presumably, Princess Pink is positively influenced by her seven older brothers in her dislike of anything girly. This is an inverse Loud House set up (Nickelodeon), in which we learn about the poor, put-upon boy who suffers through his 10 sisters.

A common bit of fathers with a wife and daughters but no sons: “I never get time in the bathroooom! I am sooo put-upon and henpecked! Argh!”

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

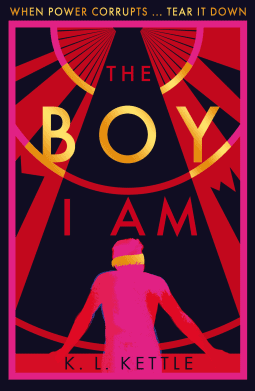

They say we’re dangerous. But we’re not that different.

Jude is running out of time. Once a year, lucky young men in the House of Boys are auctioned to the female elite. But if Jude fails to be selected before he turns seventeen, a future deep underground in the mines awaits.

Yet ever since the death of his best friend at the hands of the all-powerful Chancellor, Jude has been desperate to escape the path set out for him. Finding himself entangled in a plot to assassinate the Chancellor, he finally has a chance to avenge his friend and win his freedom. But at what price?

A speculative YA thriller, tackling themes of traditional gender roles and power dynamics, for fans of Malorie Blackman, Louise O’Neill and THE POWER.