Many people will probably tell you their first brush with death was watching Bambi. I can’t say the same because I never saw the animated Disney film. I thought I knew the story for the longest time, because my grandmother bought me a Little Golden Book called Bambi and Friends Of The Forest. I still have it, because Nana’s wobbly handwriting is in the front. Bambi and Friends is like an extended scene like that one out of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, where Snow White is frolicking with the animals in the forest. In this Little Golden Book there is no death.

The first literary death to really affect me came much later at age 11 when I read Anne of Green Gables. It was interesting to watch Anne With An E (the Netflix series) and see that Matthew does not die in this more modern revisioning. What was behind that decision? By keeping Matthew alive, Walley-Beckett refused to give him tragic hero status. Instead, she turns him into a more flawed human being, whose lack of communication to Marilla about their shared financial position posits him as a patriarchal (though kind) man of his time.

Back to Bambi…

DEATH IN BAMBI

I was first introduced to death by my older sister who took me to see the movie Bambi when I was a little girl. I’d barely dried my tears over the death of Bambi’s mother, when I was crying again while reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s book By the Shores of Silver Lake. Not only did Laura’s sister Mary go blind, but their loyal bull dog, Jack, died. In high school I reached for the tissue again when Scarlet O’Hara’s elderly father dies in Gone with the Wind.

Even then, I wondered why did writers let people and beloved animals die? I didn’t think it was too much to ask those with the power of make believe to keep everyone alive.

Susanne Brent, WoW

Bambi could’ve been worse, ya’ll. Or maybe it would have been better..?

Walt Disney wanted not just one death, but two. […] Walt wanted to add the image of a man’s hand in the fire sequence, showing that the flames came at the hands of man, and that same fire destroyed the cause of all the chaos, too.

Believe It Or Not, Bambi Was Originally Even Sadder, from Refinery29

The duty of the writer … is to remind us that we will die. And that we aren’t dead yet.

Solmaz Sharif

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DEATH IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

In literature produced for children in earlier centuries, death was nearly omnipresent—either as a reward for spiritual righteousness and moral rectitude or as a punishment for wicked, ungodly behaviour.

In the earliest collection of Grimm fairytales (which admittedly, weren’t really for children), you see the link between life and death really clearly in endings such as:

- And if they haven’t died, they’re still alive.

- They were once again together and lived happily ever after until the end of their days.

- They lived happily together until they died.

For medieval people, death wasn’t really considered tragic. I guess medieval people had a lot more confidence in their after life beliefs. They were DEAD sure they weren’t going to die. Only their corporeal bodies died. This is why The Little Match girl has a HAPPY ending. The girl meets up with her grandmother and they live together in Heaven! Elisabeth Kubler-Ross, in her seminal book about death said that, there are two kinds of people who are most at peace on their death beds. The super religious and the super atheist. But most of us fall in the murky middle, and find death pretty terrifying.

Fast forward to the 20th century and Western civilisation no longer feels quite as optimistic about life after death. Though death was a common theme in 19th century fiction for children, it was almost banished during the first half of this century.

Since then it has begun to reappear; the breakthrough book was E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. In contemporary children’s literature, not only animals but people die, notably in the sort of books that get awards and are recommended by librarians and psychologists for children who have lost a relative. But even today the characters who die tend to be of a generation or two older; the main character and his or her friends tend to survive.

Though there are some interesting exceptions, even the most subversive of contemporary children’s books usually follow these conventions. They portray an ideal world of perfectible beings, free of the necessity for survival and reproduction: not only a pastoral but a paradisal universe — for without sex and death, humans may become as angels. The romantic child, trailing clouds of glory, is not as far off as we might think.

Alison Lurie, The Subversive Power Of Children’s Literature

Roberta Seelinger Trites has a theory about death and sex as its inverse:

I have always suspected that authority figures in our culture protect children from knowledge of sex because of our cultural desire to protect children from a knowledge of death. Philippe Aries refers to this as the “interdict laid upon death” in the twentieth century. The romantic image of the innocent child still dominating our culture perpetuates the illusion that children flourish best if they are free from the corrupting knowledge of carnality. Carnality: sex and death, death and sex. They are cultural and biological concepts that are linked inviolably.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

But what’s a story without carnality? Boring, that’s what. Children’s authors avoid sex and death, but they do include lots of eating as a stand-in.

DEATH IN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE

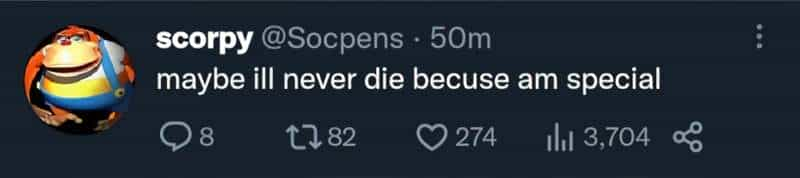

Young adults are seventy-six times more likely to die in a YA novel than in actual life.

Nicole Galante – A Genre Against Them: Regulating Young Adults Through Literature

Everything said above applies to children’s literature but not young adult literature. The rules are quite different here.

Seelinger Trites makes the point that ‘mortality’ is different from ‘death’. In junior fiction, an understanding of mortality — as part of the cycle of life — is part of a symbolic separating from parents. YA characters learn that death is about more than just separating from parents. Teenage readers are now understanding that death might be completely and utterly final, and that’s terrifying.

Seelinger Trites posits death as the defining difference between YA fiction and every other type of fiction (junior and adult) — the sine qua non, the defining feature. YA novels are all about the death, but not from a variety of different angles. Not like adult literature. Young adult novels deal with a very specific aspect of death:

In adolescent literature, death is often depicted in terms of maturation when the protagonist accepts the permanence of mortality, when she/he accepts herself as Being-towards-death.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

Heidegger’s Being-toward-death

That concept Being-towards-death is key.

- The main character not only acknowledges their separateness as an individual from the dead character

- And is well aware of the finality of it, but

- The death influences the main character’s maturation.

- They recognise their own mortality, not just as a concept but for real.

Here’s what the Anagnorisis arc tends to look like in these stories:

- Realization that if this person I’m close to has died, then I too will be dead someday. An emotional storm around this.

- A bit of calm to follow

- The main character ends up better off than they were before, because now they really understand the power of death, they can make the most out of life. Alongside that, they realise their own tragic vulnerability and experience a heightened awareness of what power they do and do not hold in their lives.

It seems that death has far more power over the adolescent imagination than any human institution possibly could.

Roberta Seelinger Trites, Disturbing The Universe

Seelinger Trites goes on to describe 3 recurring patterns in YA literature:

- DEATH OCCURS ONSTAGE — In MG novels death tends to happen off stage, reported back by characters, or occurring right at the beginning of the story before the audience has had a chance to bond with the dead character. YA novels make the death far more immediate. We’re often right there for the death.

- DEATH IS UNTIMELY, VIOLENT AND UNNECESSARY — Whereas MG novels tend to kill off the elderly and parental figures, YA novels kill the young.

- TRAGIC LOSS OF INNOCENCE — When the YA character first understands the finality of death, at first it seems really tragic. But before they came to their acceptance of death they were ready for a fall. They overcome tragic vulnerability, avert catastrophe and transform the tragedy of their own mortality into some level of triumph. In this way, the YA novel isn’t so different from The Little Match Girl, who came to terms with death (okay, died) but everything was okay actually. (She reunited with her grandmother and went to Heaven.)

Main Character as Photographer

There’s this really popular narrative trope used to explore death in YA literature — the main character is a photographer. A diarist is similar. In stories about death, the young person is often the sort of personality who incorporates some kind of pause into their thinking, whether it’s by reflecting on events (often by writing events down) or by taking an actual freeze frame (via camera). This pause foreshadows the eternal pause that will eventually define death.

DESCRIBING GRIEF

It can be challenging for writers to describe grief in a way that feels both real and honest. One solution is to write about the ways in which you evade it.

Why We Find It So Hard To Describe Grief

One way of writing about death is to write symbolically. Books don’t have to feature death to be about death. Stories about solitude and darkness are also about death. For children, the darkness of night is like a kind of death.

In Lemony Snicket’s picture book The Dark, a boys’ descent into the darkness of the basement is metaphorically the Big Struggle scene in which a character comes close to death.

DEATH AND TRANSHUMANISM

First, what is transhumanism?

Transhumanism is the belief or theory that the human race can evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of science and technology.

While the transhumanist movement and goal for singularity can make sense of our increasingly science-fiction world with its rapidly growing technologies, I see problems with articulating the wrongness of death; in a recent Slate article, Joelle Renstrom writes that:

Representing death as wrong gives it greater power, especially when people do die. If death is wrong, are people who die bad, or are they victims of an obsolete paradigm? Either way, making peace with death would be particularly challenging. Kids could grow up not just afraid of death, but also afraid of failing to fix it. Stolyarov makes death a powerful nemesis that could rule their lives—just as it’s ruled his.

The notion of immortality becomes a fact rather than a concept; to present that to a young mind, a nascent consciousness, does not bode well for their development.

Transhumanism In Kidlit

Peter Pan And The Reversibility Of Death

Critics have said much about Peter and Wendy as a story about death, and adulthood as a form of death.

[T]he Neverland is unmistakably the land of the dead, with all its implications. In Mrs. Darling’s vague childhood memories of Peter, “when children died he went part of the way with them, so that they shouldn’t be frightened”. Peter’s famous statement “To die will be an awfully big adventure,” is based on the idea of reversibility of death. This is not a Christian, but a pagan (archaic) notion. To die in the Neverland is an everyday matter, and the author deals with it quite casually: “Let us now kill a pirate, to show Hook’s method”. This is only possible because it is not real death, but make-believe. Wendy is shot down by the not-so-bright Tootles and lies dead for a while, mourned by the boys, emerging from the little house in a perfect “returning-goddess” ritual. Even Tinker Bell, having taken poison, can easily be resurrected, because her life and death are merely a question of belief. If all the inhabitants of the Neverland are already dead, then of course they are not afraid to die.

[…]

Writers who choose to let their young protagonists die or commit suicide allow them to stay forever young.

From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature by Maria Nikolajeva

DEATH AND REBELLION

[I]n our Third Golden Age, we ask children to confront not only the traditional enemies such as school bullies or Dark Lords, but Death itself. Far from reassuring readers that some authority is benign, it is portrayed as unequivocally malignant, corrupted by ecological disaster, politics, greed and war. The child’s heroism lies not in following instructions but in defiance, truancy and rebellion. With the advent of YA fiction for secondary school pupils, not only death but sex has become part of the picture – in fact, with novels such as Twilight, it’s central to it.

Amanda Craig writing about the Third Golden Age of Children’s Literature

While some commentators don’t see death in young adult literature as problematic, feeling it prepares young people somehow for sadnesses in the ‘real world’, Nicole Galante disagrees, arguing that it strips young people of power in the here and now, keeping them in ‘their place’:

By looking to the future despite the death of adolescents, YA simultaneously promises future power and removes the hope of it altogether. Moreover, death is used as a threat. The young adults who die in the genre are usually those who make a grab for power before a socially acceptable time. For example, Alaska dies in Looking for Alaska after spending her teenage years drinking, smoking and having sex; Oslo in Where Things Come Back dies from an overdose, breaking the adult rule of Don’t Do Drugs; and Mary in The Absolutely True Diary of a PartTime Indian dies after moving off the reservation despite traditions that warn against it. A subtler version of this tactic is used at the close of the The Disreputable History. The narrator says, “Frankie Landau-Banks is an off-roader. She might, in fact, go crazy, as has happened with a lot of people who

Nicole Galante – A Genre Against Them: Regulating Young Adults Through Literature

break the rules” (337). Frankie isn’t dead, but being threatened with the label “crazy” disenfranchises her as a punishment for breaking the rules set in place by adults. Young adult readers’ options are as follows: wait for power and spend years sticking to the status quo, or make a grab for power and die in the process. Because both options, waiting and dying, are bleak, young adult readers can internalize the message that power is always out of reach, and therefore

they’ll never try to break the cycle of powerlessness. In this way, power remains in the hands of adults, and it becomes unfortunately evident that YA is not trying to empower young adult readers, but rather it is trying to regulate them.

Galante has two recommendations for writers of young adult literature:

- Stop relying so heavily on the future that the present is forgotten, and young adult readers are consequently rendered powerless.

- Stop killing off “rule-breaking” characters.

The following notes are from the Kid You Not Podcast, Episode 4.

- In many stories death is the beginning of the book rather than the ending.

- Death is an on-limits topic in books for all ages, from picturebooks to adult.

- Western children are otherwise completely protected from death. It’s common these days to reach adulthood without ever having witnessed death. Yet children’s literature is replete with references to death, with family members and friends dying all the time.

- In the Victorian era death was far more a part of life than it is now, but the rate of death doesn’t seem to have gone down much.

- The reality is children still have to deal with death. Grandparents are the most common.

- Many believe the function of kidlit is to prepare them for all eventualities. [Bibliotherapy is discussed in detail by David Beagley.]

- There’s definitely a demand for books on this topic. Ask any librarian. Parents want help introducing this topic to their children in a way that is safer and less personal.

- There are many, many books looking at the death of animals, as a more indirect way of learning about this topic.

- My Sister Lives On The Mantelpiece uses the death of an animal as an overt device through which the male protagonist finally understands his father’s grief for his sister, who died five years before. This book deals not with death itself but with the characters who are left behind dealing with it.

- Artichoke Hearts by Sita Brahmachari may be one of the best YA books of the past few years and in this story we see the day-to-day life of a girl who is slowly losing her grandmother to cancer.

- In fact, most children’s books are not tackling death; they tackle mourning.

- Big philosophical questions about what happens after you die are avoided. Mourning is easier to tackle, and such stories are perhaps selected for publishing because they have a therapeutic effect on young readers. The stories have endings which are not final. Phillip Pullman’s Lyra saves death in The Amber Spyglass (aka Northern Lights) because she essentially ensures that people become part of everything after death. This is a comforting idea because nothing feels final. Your life or at least your essence will continue to be part of the world.

- This is not specific to kidlit, e.g. Mitch Albom’s The Five People You Meet In Heaven [or Proof Of Heaven etc]

- Still, there is a difference between the treatment of death in children’s and adults’ literature. The difference is that in literature for adults it is okay to not be able to mourn. It is okay for a death to be completely meaningless, completely unfair and devoid of any possibility for the people who are left to grieve and achieve a wholeness in grief. In kidlit, children must at least find some sort of solace.

- The Reformative Value Of Death. This is the idea that with someone dying you can somehow gain value. This a horrible idea when you think about it, but there are numerous examples of this in children’s literature: Jacqueline Wilson’s Vicky Angel is about two best friends (extrovert/introvert). The louder child is killed in a car accident. The quiet child begins to come out of her shell. The Sky Is Everywhere by Jandy Nelson begins with Lenny grieving for her sister who died completely randomly. The novel explores Lenny’s neuroses. She was so in awe of her sister that she didn’t try anything. In both stories, death gives the girls the gift of empowerment.

- This kind of story is controversial, because the reader is encouraged to empathise wholly with the character left behind and put aside the (fictional) fact that another character has completely gone forever. Perhaps this kind of storyline is again trying to clothe death in meaning, since death almost always feels premature and unfair in real life.

- One problem with the Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins is that it anesthetizes the reader rather than preparing them for adolescent death. Another issue is that on the one hand the TV game show encourages the reader to consider adolescent death a terrible thing, but on the other hand the reader wills the protagonist to kill some of them. So some of their lives were worth more than others — a ‘lazy and convenient technique’ because, conveniently, all the characters who are killed happen to be unpleasant while the ones who survive are pleasant. [I’m reminded of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.]

- [Related: See The Hunger Games: Violence Is The Answer, in which an academic from Emory University explains how the elements of Suzanne Collins’ trilogy derive from Ancient Roman gladiatorial culture in which violence was used to keep the peace, so to speak. This Roman culture is blended with Greek Myth.]

- Death is therefore not only a theme in a lot of stories for children; it is also a plot device.

- The incredible success of Hunger Games calls into question the degree to which fascination with death works with adolescents.

- In the book Before I Die by Jenny Downham, death is used as the sole plot device. A 16 year old girl is dying of cancer. You may find yourself in tears even if you don’t think this is a particularly good book — it is incredibly manipulative of emotions. An important distinction: The reader is crying because a 16-year-old girl is dying, not because of the writing.

- Manipulation is very important. Death can be an easy way to elicit emotions from a young reader. If we consider different forms of death: accident, homicide, terminal illness and suicide, of those, suicide is perhaps the most highly problematic. Books for adolescents are completely full of references to suicide, whether people actually commit suicide or entertain suicidal ideas. There is a long tradition in literature of young protagonists who contemplate suicides. It was thought after the publication of The Sorrows Of Young Werther lots of young men were committing suicide after reading the book. [Incidentally, this is like the plot of Gloomy Sunday, a small, arty film which inexplicably took off in my hometown of Christchurch in the late 90s and had an extremely long running period at the Arts Centre cinema.]

- Similarly, the Romeo and Juliet plot is found everywhere. We find it in Twilight, Noughts and Crosses by Malory Blackman, Forbidden by Tabitha Suzuma, Harry Potter (with the self-sacrifice at the end). A lot of the time it’s clothed behind the fact that she isn’t actually dead — she becomes a vampire. Harry Potter is very Christian — very like Jesus. Self-sacrifice. Suicide is often presented as the noble option in children’s literature.

- Suicide is the third biggest cause of adolescent death. It is glorified in adolescent novels, if not for being a noble act in its own right, but for helping others to see that life is worth living. This may be problematic when adolescent brains are hardwired for risk-taking. [Most recently we have 13 Reasons Why by Jay Asher and all the discussion that came about after it was adapted as a Netflix series.]

- There’s also an argument that adolescents like living vicariously through reading these books. The books provide the distance and can help them get through the teen years.

- The problem with suicide is that hearing about it triggers the risk in people who are depressed or otherwise at risk. We can’t always hide behind the idea that vicarious experiences are safe ones.

- At the opposite extreme, death is sometimes treated in a comical fashion. Examples: Casper the Friendly Ghost, Harrybo by Michael Rosen

- If death is treated humorously, this may be a better way of helping children deal with death, de-dramatizing it but at the same time acknowledges it is a thing.

It seems that in YA novels, there may be only two ways to deal with growing up, death or self-denial.

Maria Nikolajeva, From Mythic to Linear

- Paranormal romance is a genre which seems to indulge a teenager’s fascination with death. Death is not the end in any of the stories — they’re completely escapist. The premise of Fallen by Lauren Kate is reincarnation. Every time the character dies she is reborn. Twilight is literally an ode to living forever. They seem very gothic but in fact they evade the theme of death completely.

- By putting so much death in their children’s books, adult writers are taking the easy way out, clothing their own fears in pretty words and images. One day there will be a true text which deals with death in a meaningful way. Duck, Death and the Tulip by Wolf Erlbruch is a beautiful (but controversial) picture book because it presents the inextricable link between a person and death.

The following short film, based on the picture book, shows that when it comes to writing about hard stuff for kids, it’s about the treatment rather than the subject matter. The short film is far darker than the tone of the picture book.

- Could children’s literature even exist if there were no such thing as death? Is part of the reason adults want to tell children all about life (through stories) because they know that they are going to die?

- Perhaps adults simply think that children can’t cope with death. It’s the easy way out and it’s very often what adults believe themselves.

- Remember, we don’t see the books that don’t get published. Publishers are less willing to take risks on books that won’t sell. Parents are the book-buyers. Librarians and teachers are other gatekeepers. There’s a huge amount of adult pressure outside the publisher and author regarding what children will read. Kidlit is a sample of what adults think children can deal with. It seems adults think children need to understand that there is ‘transience’ but few are willing to really get into the nitty gritty harshness of death.

THE 1970S TENTPOLE BOOK ABOUT DEATH: BRIDGE TO TERABITHIA BY KATHERINE PATERSON

Bridge to Terabithia [like] The Brothers Lionheart, [has] been repeatedly referred to as a good novel to introduce death to young readers. However, it is not a book about “coping with death”, but rather about the hard work of growing up, told not from the point of view of an omniscient and didactic adult, but that of an inexperienced and therefore vulnerable child.

Maria Nikolajeva: From Mythic to Linear: Time in children’s literature

Katherine Paterson’s moving Bridge to Terabithia (1977) has death as a theme. Jesse Aarons is introduced to the world of the imagination by his new friend Leslie (a girl); together they set up a secret kingdom in the woods beyond the creek. One day Leslie falls into the creek and is drowned; Jesse must survive his grief, and does so to the extent of building a (surely symbolic) bridge across which he can bring his small sister. Leslie’s death is sudden and not witnessed by Jesse, so to some extent the reader is spared.

John Rowe Townsend, Written For Children

CHILDREN’S BOOKS ABOUT DEATH

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White (1952) — Ditto. Wilbur knows all about death but he doesn’t let it consume him.

A Summer To Die by Lois Lowry (1977) — Thirteen year old Meg must live through her sister Molly’s terminal illness, and sees Molly in hospital close to death.

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbit (1975) — You can’t look past this book in any discussion about children’s literature and death. Doomed to – or blessed with – eternal life after drinking from a magic spring, the Tuck family wanders about trying to live as inconspicuously and comfortably as they can. When ten-year-old Winnie Foster stumbles on their secret, the Tucks take her home and explain why living forever at one age is less a blessing that it might seem. Complications arise when Winnie is followed by a stranger who wants to market the spring water for a fortune.

“Don’t be afraid of death; be afraid of an unlived life. You don’t have to live forever, you just have to live.”

Natalie Babbitt

Cousins by Virginia Hamilton (1990) — This is a moving book written by America’s first great black writer, winner of the Newbery. It is the story of eleven-year-old Cammy, who must come to grips with the sudden death of her cousin and rival, Patty Ann.

Missing May by Cynthia Rylant (1992) — About the adjustment of an old man and a young girl to the death of the old woman who was wife to one and dearly-loved aunt to the other. (The death of an elderly person is not as gut-wrenching as the death of a child character.) When May dies suddenly while gardening, Summer assumes she’ll never see her beloved aunt again. But then Summer’s Uncle Ob claims that May is on her way back—she has sent a sign from the spirit world. Summer isn’t sure she believes in the spirit world, but her quirky classmate Cletus Underwood—who befriends Ob during his time of mourning—does. So at Cletus’ suggestion, Ob and Summer (with Cletus in tow) set off in search of Miriam B. Young, Small Medium at Large, whom they hope will explain May’s departure and confirm her possible return. The characters learn that they won’t begin to accept May’s death until they let go of supernatural hopes of meeting her again.

Undone by Brooke Taylor (2008) — When Kori Kitlzer, the “dark angel” of the 8th grade, tells Serena Moore that they are more alike than she thinks, Serena is instantly intrigued. As their friendship solidifies and their lives entwine, Serena tries to become more like the fearless, outspoken, and ambitious Kori. Soon Serena doesn’t know where she begins and Kori ends. But when a twist of fate yanks Kori away from Serena, she will need to find a way to complete her best friend’s life left undone. Undone is a novel about friendship, family, and the secrets we keep from the people to whom we are closest.

Liar by Justine Larbalestier (2009) — Micah will freely admit that she’s a compulsive liar, but that may be the one honest thing she’ll ever tell you. Over the years she’s duped her classmates, her teachers, and even her parents, and she’s always managed to stay one step ahead of her lies. That is, until her boyfriend dies under brutal circumstances and her dishonesty begins to catch up with her. But is it possible to tell the truth when lying comes as naturally as breathing? Taking readers deep into the psyche of a young woman who will say just about anything to convince them—and herself—that she’s finally come clean, Liar is a bone-chilling thriller that will have readers see-sawing between truths and lies right up to the end. Honestly.

Adios Nirvana by Conrad Wesselhoeft (2010) — Since the death of his brother, Jonathan’s been losing his grip on reality. Last year’s Best Young Poet and gifted guitarist is now Taft High School’s resident tortured artist, when he bothers to show up. He’s on track to repeat eleventh grade, but his English teacher, his principal, and his crew of Thicks (who refuse to be seniors without him) won’t sit back and let him fail.

You Are Not Here by Samantha Schutz (2010) — Annaleah and Brian shared something special – Annaleah is sure of it. When they were together, they didn’t need anyone else. It didn’t matter that their relationship was secret. All that mattered was what they had with each other. And then, out of nowhere, Brian dies. And while everyone else has their role in the grieving process, Annaleah finds herself living outside of it, unacknowledged and lonely. How can you recover from a loss that no one will let you have?

Dead Beautiful by Yvonne Woon (2010) — On the morning of her sixteenth birthday, Renée Winters was still an ordinary girl. She spent her summers at the beach, had the perfect best friend, and had just started dating the cutest guy at school. No one she’d ever known had died. But all that changes when she finds her parents dead in the Redwood Forest, in what appears to be a strange double murder. After the funeral Renée’s wealthy grandfather sends her to Gottfried Academy, a remote and mysterious boarding school in Maine, where she finds herself studying subjects like Philosophy, Latin, and the “Crude Sciences.” It’s there that she meets Dante Berlin, a handsome and elusive boy to whom she feels inexplicably drawn. As they grow closer, unexplainable things begin to happen, but Renée can’t stop herself from falling in love. It’s only when she discovers a dark tragedy in Gottfried’s past that she begins to wonder if the Academy is everything it seems. Little does she know, Dante is the one hiding a dangerous secret, one that has him fearing for her life.

Dear Anjali by Melissa Glenn Haber (2010) — Twelve-year-old Meredith’s world is rocked when her best friend Anjali dies from a sudden viral infection. In letters to Anjali, Meredith puzzles through how to cope with the ongoing challenges of school and regular life—without Anjali by her side. Complicating matters is the new friendship Meredith develops with Noah, the object of a crush she and Anjali once shared. Meredith’s connection with Noah leads first to guilt as the two grow closer…and ultimately to revelations that could shatter every memory Meredith holds dear regarding her lost friend.

Abandon by Meg Cabot (2011) — Though she tries returning to the life she knew before the accident, Pierce can’t help but feel at once a part of this world, and apart from it. Yet she’s never alone . . . because someone is always watching her. Escape from the realm of the dead is impossible when someone there wants you back. But now she’s moved to a new town. Maybe at her new school, she can start fresh. Maybe she can stop feeling so afraid. Only she can’t. Because even here, he finds her. That’s how desperately he wants her back. She knows he’s no guardian angel, and his dark world isn’t exactly heaven, yet she can’t stay away . . . especially since he always appears when she least expects it, but exactly when she needs him most. But if she lets herself fall any further, she may just find herself back in the one place she most fears: the Underworld.

So Shelly by Ty Roth (2011) — Until now, high school junior, John Keats, has only tiptoed near the edges of the vortex that is schoolmate and literary prodigy, Gordon Byron. That is, until their mutual friend, Shelly, drowns in a sailing accident. After stealing Shelly’s ashes from her wake at Trinity Catholic High School, the boys set a course for the small Lake Erie island where Shelly’s body had washed ashore and to where she wished to be returned. It would be one last “so Shelly” romantic quest. At least that’s what they think. As they navigate around the obstacles and resist temptations during their odyssey, Keats and Gordon glue together the shattered pieces of Shelly’s and their own pasts while attempting to make sense of her tragic and premature end.

The Trouble With Half A Moon by Danette Vigilante (2011) — Ever since her brother’s death, Dellie’s life has been quiet and sad. Her mother cries all the time, and Dellie lives with the horrible guilt that the accident that killed her brother may have been all her fault. But Dellie’s world begins to change when new neighbors move into her housing project building. Suddenly, men are fighting on the stoop and gunfire is sounding off in the night. In the middle of all that trouble is Corey, an abused five-year-old boy, who’s often left home alone and hungry. Dellie strikes up a dangerous friendship with this little boy who reminds her so much of her brother. She wonders if she can do for Corey what she couldn’t do for her brother—save him.

See also: The Influence Of The Lovely Bones, which is a post about dead narrators.

Quite a few children’s novels have death, the fear of death, and “coping with death” as a central or peripheral motif, and writers can deal with death as an “issue” (“How to help children cope with the death of a relative”) or an existential problem, in a realistic (Bridge to Terabithia) or fantastic (The Brothers Lionheart) mode. Most often, the person who dies in a children’s book is the protagonist’s older relative, quite often a pet (“transitional object”), more rarely a parent, occasionally a sibling or a friend. The event very rarely concludes the novel, as Forster suggests; on the contrary, it is introduced in the beginning to set the plot in motion. By the end of the book, the trauma has been successfully healed. In many novels, the parents’ death (utter form of “absence”), as in fairy tales, is the necessary prerequisite for the character’s quest (The Secret Garden).

The treatment of death in children’s literature has changed radically during the past two hundred years, as has the general attitude with regard to death in our society. While the nineteenth-century practice of letting the young protagonist die may seem improper to us today, it reflects the contemporary views on childhood as the period of blissful innocence, the Christina perspective on death as well as the actual child mortality of that time. Today we may view the ending to Andersen’s The Little Match Girl as tragic; Andersen’s contemporaries were supposed to see the happy reunion of the child and her grandmother in heaven.

The taboo on death in children’s literature during the first half of the twentieth century gave way to a more serious treatment of the theme in contemporary psychological children’s novels. … death is one of the three essential components of human growth, together with the sacred and sexuality, and therefore always present in children’s fiction in some form.

Maria Nikolajeva, The Rhetoric of Character in Children’s Literature:

Of Swedish children’s books in the 1960s and 70s, Nikolajeva writes in Children Literature Comes Of Age:

Almost everything in a child’s life is presented as a problem: to get a new sibling, to start school, to move into a big city. At the same time there is a treatment of more serious questions such as the child’s response to death. In Sweden of the 1960s and later, where most old people die in hospitals and the majority of the children never see a dead person, death becomes something alien and dreadful. More and more commonly, therefore, death and the child’s contemplation of death appear as a secondary motif in some children’s books and the central theme in others. Young adult novels went still further in this direction, depicting young people’s suicide attempts or, in extreme cases, even accomplished suicides.

This was a necessary and understandable reaction to earlier idyllic children’s literature, which wished to spare young readers the less attractive sides of society. But as the socially committed code dominated children’s literature, all other codes were banished to the periphery, among them the imaginative code of the fairy tale and fantasy.

As a motif, death has played a large role in children’s literature from the start:

…investigations of the motif of death in children’s literature could examine how, in fantasy, it can feature as a way of overcoming time and space, for instance as a gateway to fantastic adventures in Astrid Lindgren’s The Brothers Lionheart (1973), or how it combines the aesthetic and the erotic, especially in the death of young girls. Death becomes the prettily staged literary fate of girls who will never grow up — or never be allowed to grow up — to become women. Female exuality is not permitted to develop and its repression mingles with the eroticism expressed in the extinction of the budding woman thus rendered permanently chaste and safe from violation, age and corruption: nothing can be purer than a girl who dies a virgin. The link between death fantasies and erotic desire is evident in stories such as Johanna Spyri’s Gritli’s children (1883), in which an old nurse acts as a kind of go-between, presenting death as desirable in poems and stories, while two girls have ‘forbidden’, intimate conversations about dying. Nineteenth-century British fantasies for children, too, are pervaded by ‘the presentation of death as seductive and desirable.

Comparative Children’s Literature by Emer O’Sullivan

Every single time I see a take that amounts to “if you write about X happening, or like fiction where X happens, you like X” I’m reminded of this one time I was at a casual friends house as a young kid. We were in her room, pretending to “be orphans” escaping from an evil orphanage and having to take care of each other and fend for ourselves. It was all very Little Orphan Annie/All Dogs Go to Heaven and based on the 80s pop media.

And this girl’s mom comes in, hears what we’re playing and gets all MAD and UPSET. She says that if we play act something, it’s because we want it to happen. So her daughter must WANT HER TO DIE.

First off lady, we were 6 year year olds, so take it down several notches. We barely had a concept of mortality for fucks sake. She made us feel so guilty and ashamed, because she was taking our game personally.

Now I have a 5 year old. And sometimes she looks at me and says “pretend you’re dead, and I have to -” Whatever it is. Some adult task she’s assigned herself.

And it’s just so transparently obvious that she’s practicing the idea of having to do things on her own. Which is exactly what 5 year olds are supposed to do. I actually find it very flattering that the only way she can envision me not being available to help her is to be literally deceased. Otherwise, obviously, she wouldn’t have to do scary hard things alone.

It’s a natural coping mechanism. She’s self-soothing about what would happen if I wasn’t there by play-acting independence in a perfectly safe environment. She’s also practicing skills she needs, and making up excuses for practicing them on her own, without taking on the responsibility of being able to do them by herself all the time yet.

Humans mentally rehearse bad this in their brains all the time. We can do that by ruminating- going over worries over and over again, which tends to lead to anxiety and helplessness and depression. Or we can do it with a sense of play- by recognizing that the fiction is fiction and we can dip our toe into these experiences and expose ourselves to bad things without actually being injured.

My daughter does not want me dead. And I don’t want bad things to happen in real life. But fiction and pretend help me face the horrors of the world and think about them without collapsing or messing myself up mentally.

leebrontide on Tumblr

RELATED LINKS

Some lists on Goodreads:

- Picture Books Where Someone Dies

- Ageing and Death In Folklore, a collection of links

- For more books on this theme see the Death and Dying Matrix (a downloadable Word document).

- The wonderful Mighty Girl website also has a search function whereby you can find books dealing with death.

- See the post ‘Helping Children Cope With Death‘ from the Teach With Picture Books blog.

- Death Becomes YA Lit, from Kirkus

- You Owe Me, by Miah Arnold

- Stephen Cave: a TED talk on The 4 Stories We Tell Ourselves About Death

- From io9: All The “Cry Scenes” That Prove Animated Films Are Anguish Porn

- Death In Literature, a LibraryThing list, which includes a few kids’ books but is mainly adults’ books

- Some recommended books about death from M. Jerry Weiss

- Why death is so important in young adult literature by author Rupert Wallis

Younger individuals and people with lower levels of education attainment were more likely to have negative attitudes to death. However, it is not all bad news for these individuals. For example, we found there was a relationship between mortality fearfulness and placing a high value on staying healthy.

Why being aware of your mortality can be good for you

This is an inelegant segue, but at your age, you must think about death now and then. Does it scare you? I’m not scared of death. I don’t know what it is. How could I be afraid of something I don’t know anything about?

It’s something a lot of people are scared of. They just think they know death because other people say it is something to be scared of, but they don’t know that it is a frightening thing. Do you?

Nope. No, you don’t know what it is. People say it is this and it is that. But they don’t know. They’ve not been there. I’ve not been there. I’m not in a hurry to go either! I take it a day at a time, David, and I’m grateful for every day that God gives me.

Interview with Cicely Tyson, New York Times

THE SERIOUSNESS OF CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

We shouldn’t be dismissive of the popularity of children’s literature among adults, as it is often in these works of fiction that powerful themes such as death, love, and virtue are most deeply and imaginatively explored.

Guests:

New Books Network

- Christina Phillips Mattson, Scholar of Children’s Literature

- Casper ter Kuile, Ministry Innovation Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and co-host of “Harry Potter and the Sacred Text”

- MG Prezioso, Contributing writer for Harvard Political Review