Humans have been making transactions with money for about 5000 years. Before that, our ancestors traded goods; before that, favours. We are a species highly attuned to swapping, making deals, owing favours and keeping stock.

So it’s not surprising that we personify ‘fate’ or ‘life itself’ or God or whatever, and feel, deep down, that if one good thing happens to us we must make a sacrifice later. Sacrifice as a cultural practice has largely disappeared around the world but has it really gone away?

The emotions which drive deal with the devil stories are very much alive. Humans have developed various ways of dealing with inequalities. Here’s how an anthropologist puts it, in relation to supernatural and Pentecostal beliefs in parts of Papua New Guinea:

Witnessing inequalities in attractiveness, wealth, or health, provokes feelings of either pity or poverty depending on perspective. To rectify this imbalance, the morally appropriate response is the exchange of a gift that reestablishes mutual respect and recognition: “Until … the feeling of imbalance is counteracted, the perception of imbalance has the potential to assume a negative form, jealousy, that may lead to destructive actions” (Bashkow 2006: 123).

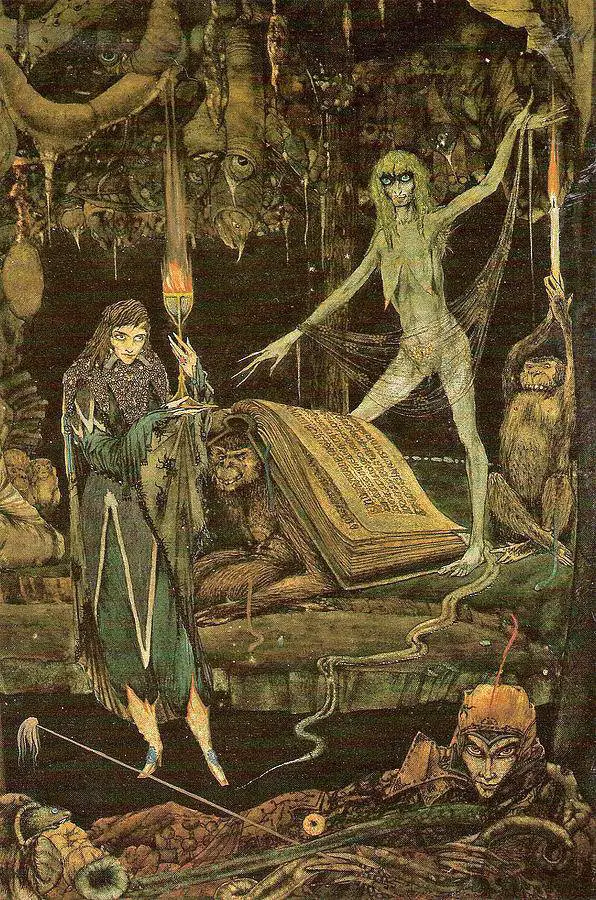

Becoming Witches

This post is about Faustian stories.

WHERE TO LISTEN

I’ve previously written about a related concept known as the ‘tragic dilemma‘. Also related is the pyrrhic victory. We could plot these outcomes on a continuum — all would be clustered at the tragic end.

You may hear the term ‘inflection points’ to describe the metaphorical crossroads we encounter in life. Psychologists use this term and investors use it as well.

WHAT IS A FAUSTIAN STORY?

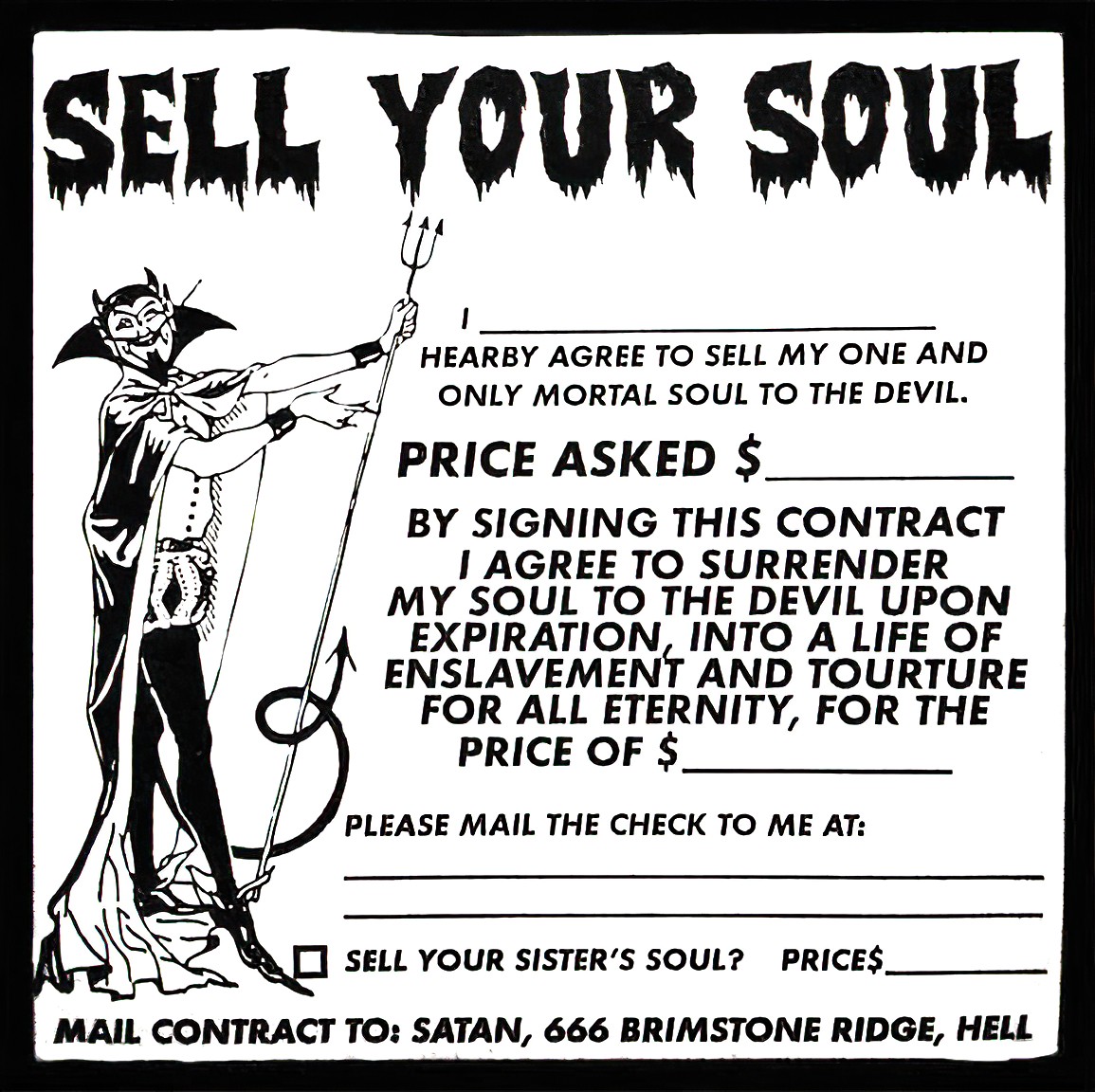

The Faustian story is an ur-story, which means it’s the ancestor of many modern tales. TV Tropes calls Faustian plots Deal With The Devil plots.

Many stories, Faustian or not, include a stark ‘moral dilemma’ scene. The Faustian story is one in which the moral dilemma is taken to its extreme: Great riches and the hero’s very life. Alternatively, if the main character chooses ‘no deal’, no riches at all and nothing good, ever. Faustian stories are a thought experiment regarding sacrifice: Everyone has a price. What would yours be?

“Faust” and the adjective “Faustian” now imply, more widely, a situation in which an ambitious person surrenders moral integrity in order to achieve power and success for a delimited term.

But the story of Dr Faustus wasn’t the only ‘Faustian’ tale in the first 1000 years after Christ. Medieval audiences really liked the tale of the guy who sold his soul to the devil.

We also have the similar tale of Theophilus, who started to bitterly regret denouncing Christ and the Virgin in favour of Satan, so he repented. After that he was known as Theophilus the Penitent. The contract with Satan got burnt up. This was a Faustian tale but it was also a redemption tale. (Audiences love those, even today. Especially in America.)

The story of Faustus became the most enduring because it coincided with a time in the medieval era — the 1500s — when certain privileged men were starting to become really schooled up in certain esoteric areas. We take it for granted these days that every professional has their speciality, and no one outside that profession will ever understand what goes on in that specialty area, but in Medieval times, if you had a specialised job, people thought you a sorcerer. Ironically, it was in the age of Newton that these ideas were in the air. Turns out we have always been suspicious of science:

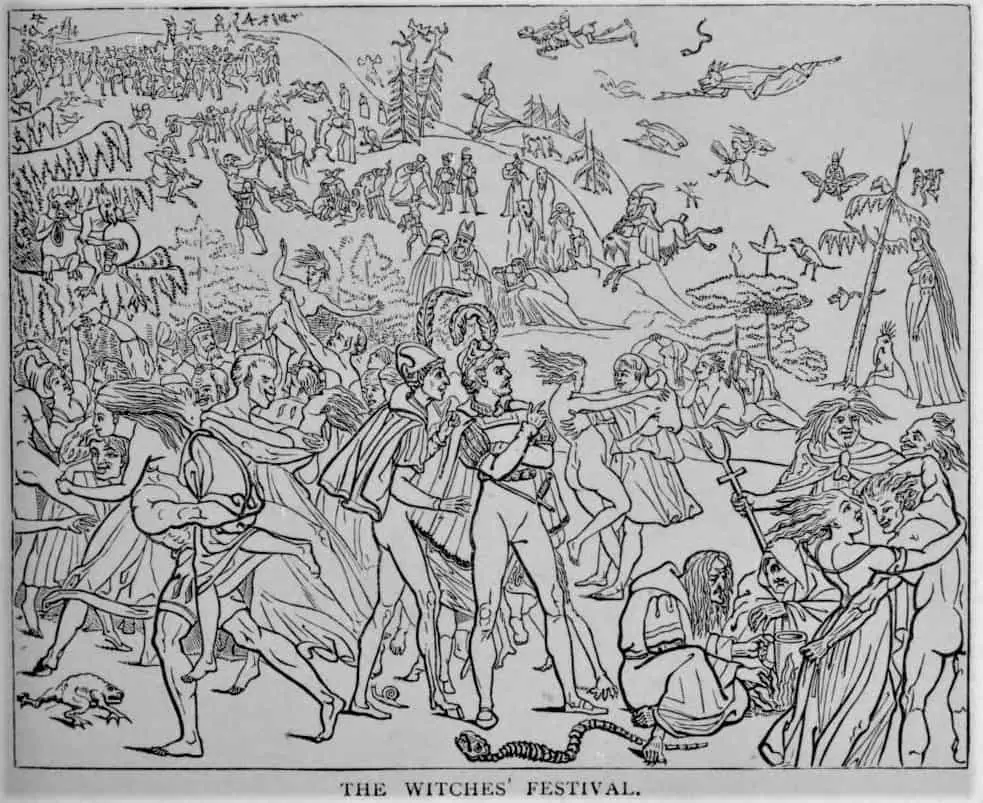

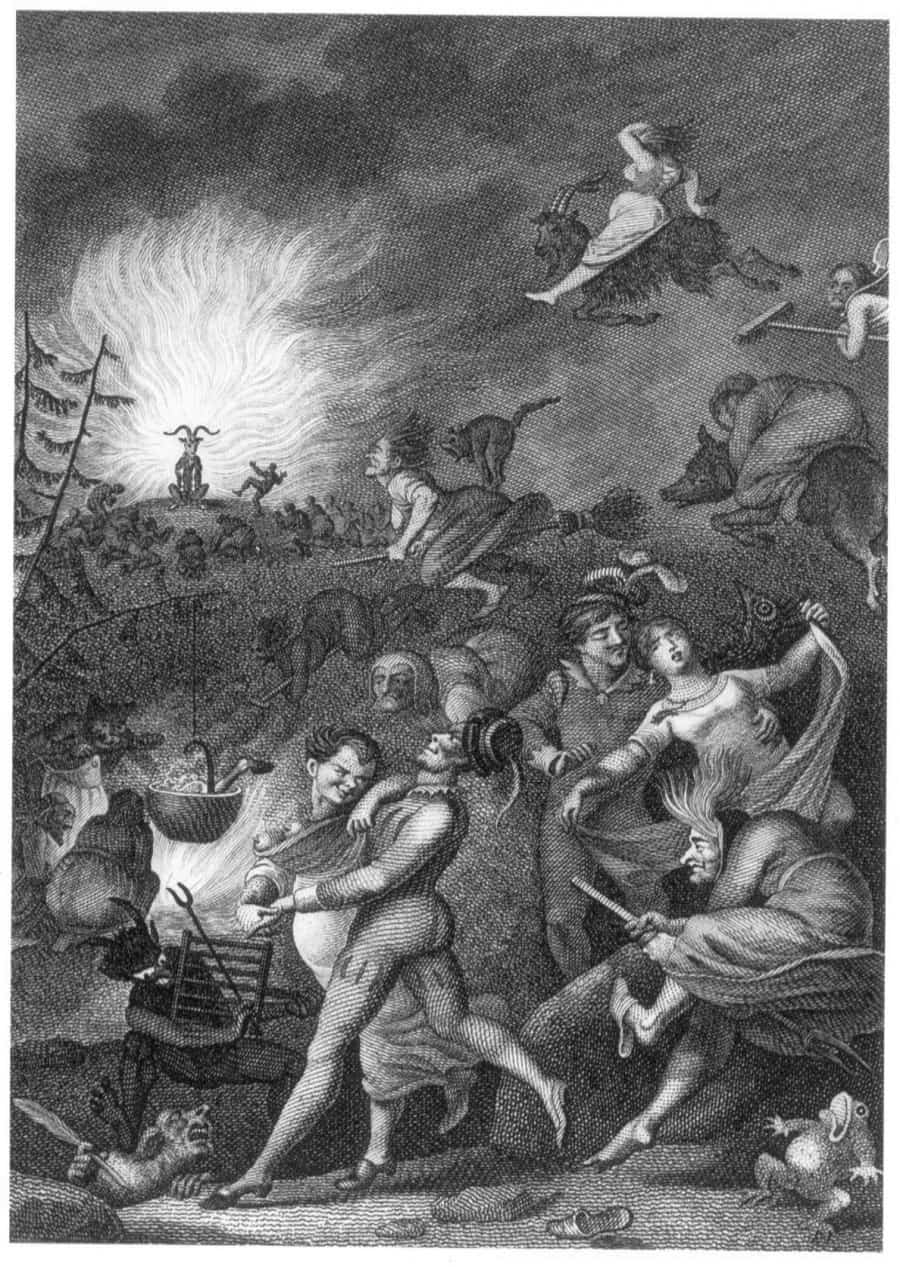

It was medieval philosophers who argued that revelation was to be found hidden in nature, and uncovered by experiment. This was the true scientific revolution. And it was Newton’s age that was the great age of superstition. It was in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that people started to believe that human beings could make a pact with the Devil, and thereby gain supernatural powers.

Medieval Lives by Terry Jones

Faust is the main character of a classic German legend. Fictional Faust is a scholar who is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life. This leads him to make a pact with the Devil, exchanging his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures.

But the fictional character of Faust is based on a real man. Johann Georg Faust, born around 1480. He was well-known as an astrologer (an academic in those days) and a necromancer (talking to the dead). He used a magic lantern to conjure up shadows of the dead, which, yes, I can see how people thought that a bit creepy.

The real life Faust was born in Kundlingen but settled longest in Witternberg. He died around age 40 because his chemicals exploded during an accident. If that’s not an interestingly tragic life, I don’t know what is. People at the time thought so, too.

The story of Faust’s life was first published in Frankfurt but had been translated into English by 1592. The title is wonderful: The History of the Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus. Whoever translated the German story into English (known only by the initials PF), added many embellishments of their own. This was common back then. I suppose it enlivened the job of translator.

Playwright Christopher Marlowe turned the story into a play which proved very popular with audiences. (Marlowe was born the same year as Shakespeare, to put it in context.) Marlowe called the play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. Don’t know about you, but that sounds to me like something Anne Shirley might have come up with.

The story of playwright Christopher Marlowe is as interesting as the story of Dr Faustus. Marlowe was a gay blaspheming atheist at a time when all three of those things were not permitted, but he was actually killed in a tavern brawl over the payment of a bill. Gory as it would’ve been to watch, I wonder how that evening played out exactly.

In any case, we might suspect Marlowe himself had made a pact with the devil. After an illustrious career as a playwright, he was executed at the tender age of 29.

Christopher Marlowe wrote his play, but Goethe also had a go at the Faustian story. Goethe was a German writer born in the mid 1700s. Goethe wrote his Faust story as a ‘closet drama’, which looks like a play on the page, but which is never intended to be performed, but read by a solitary reader ‘in their closet’. It is Goethe’s version which is now known as the Ur-story of Faust.

PLOT SUMMARY OF THE GERMAN LEGEND

The Pact

- Faust is bored and depressed with his life as a scholar. Desperately looking for a purpose in life.

- Faust tries to kill himself but botches the job. Starts with a suicide. Suicide is considered sinful by the Christian church of this time.

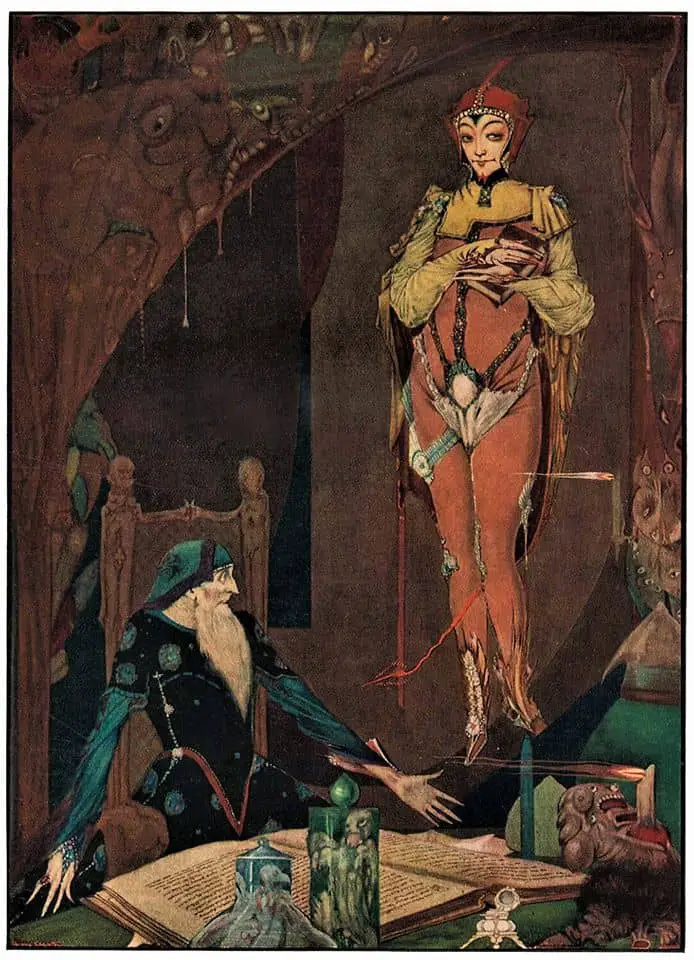

- Faust calls on the Devil. He wants further knowledge and magical powers which will let him indulge in all the pleasures of the world.

- In response, the Devil’s representative, Mephistopheles, appears.

- Mephistopheles makes a bargain with Faust: Mephistopheles will serve Faust with his magic powers for a set number of years, but at the end of the term, the Devil will claim Faust’s soul and Faust will be eternally damned. (In the early tales it is usually for 24 years, one year for each of the hours in a day.)

More On Mephistopheles

Mephisto/Mephistopheles is a character of Germanic origin. He appeared around the time of the Renaissance and comes out of medieval beliefs and traditions around carnival. He appears in the carnivals around Lent. He has a white face (a death mask). He is said to be a ‘fallen angel’, but he has godlike aspects. He is supposed to have created ocean animals.

Mephisto bcame jealous of humans so teamed up with Lucifer. He is connected to the underworld and represents temptation. (Lent is all about resisting temptation.)

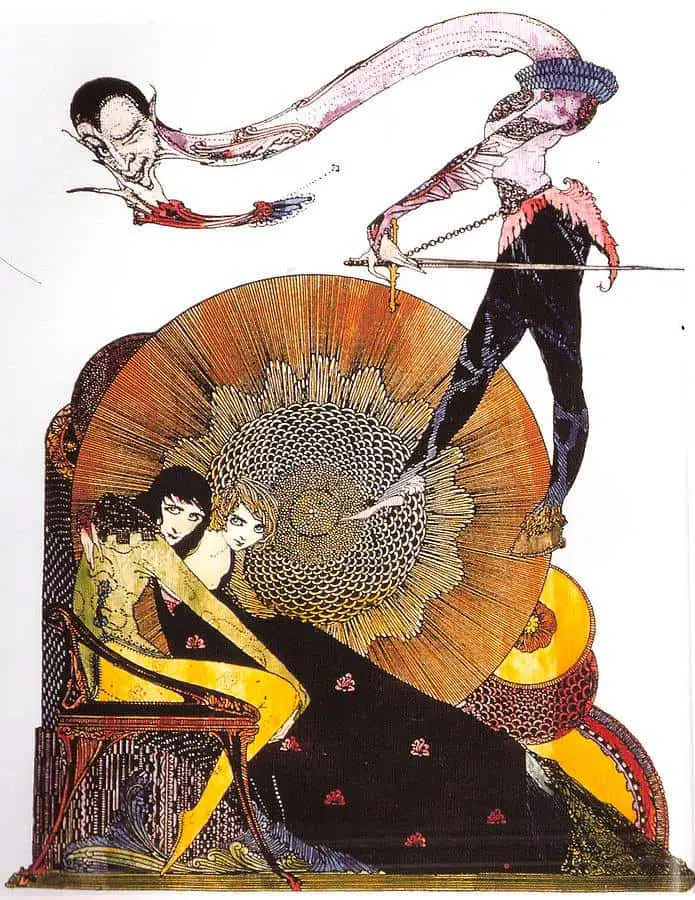

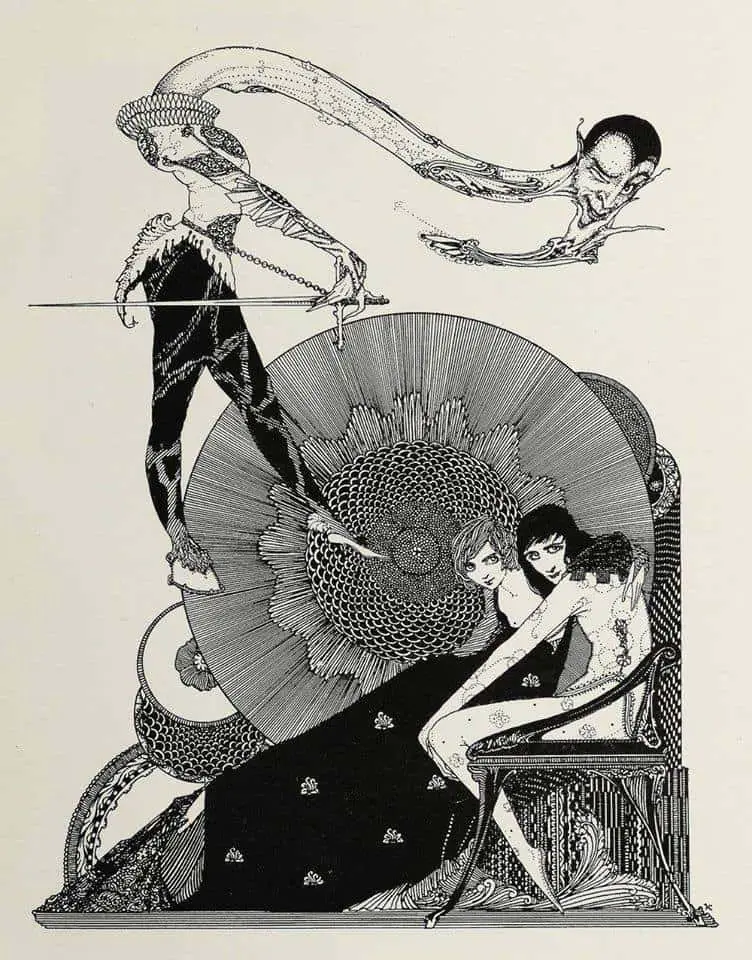

Lent is a very old carnival, but in later carnivals, the character of Harlequin and Mephistopheles become intertwined. In make-up, both are sometimes portrayed with that white face and the sweeping black line above one eyebrow that’s meant to signify intellectual arrogance. (See Gustaf Grundgens’ famous Mephisto make-up.)

The Term Of The Bargain

- Faust makes use of Mephistopheles in various ways.

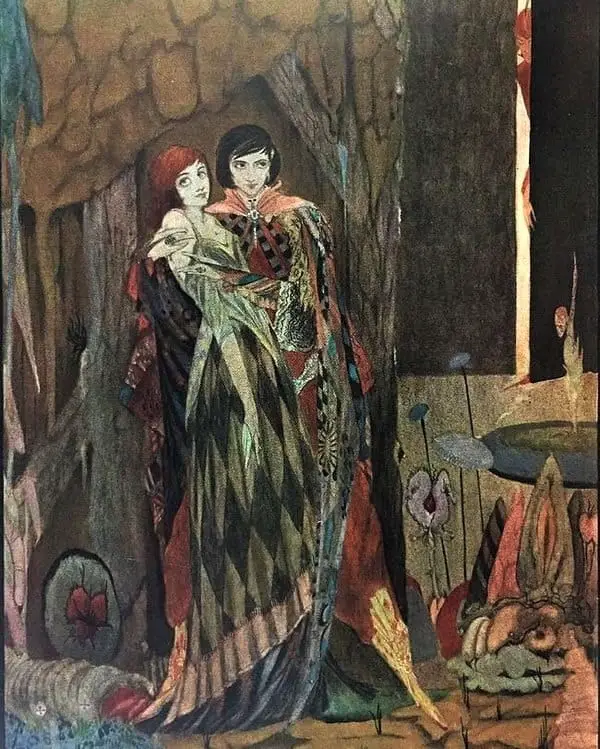

- In many versions, Mephistopheles helps Faust seduce a beautiful and innocent girl, usually named Gretchen, whose life is ultimately destroyed. However, Gretchen’s innocence saves her in the end, and she enters Heaven. [Misogynistic bullshit, typical of the era. Perhaps an early take on the Manic Pixie Dream Girl.]

- In Goethe’s rendition, Faust is saved by God’s grace via his constant striving—in combination with Gretchen’s pleadings with God in the form of the Eternal Feminine. [Happy Ending]

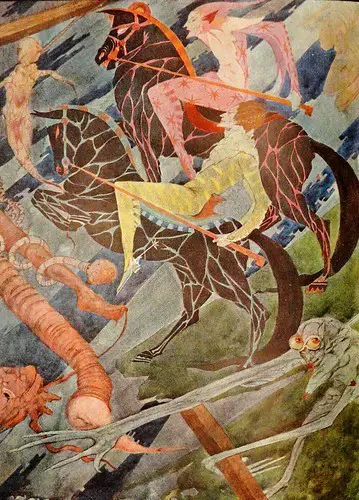

- However, in the early tales, Faust is irrevocably corrupted and believes his sins cannot be forgiven. When the term ends, the Devil carries Faust off to Hell. [Tragic Ending]

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF THE FAUSTIAN PLOT

WE ARE BLOODTHIRSTY

First, audiences really seem to like it when bad acts are justly punished. This remains true in Hollywood today and speaks to an inherent conservatism. Adult audiences (at least) also seem to appreciate when bad children are punished in children’s stories. The Faustian punishment is the ultimate punishment. It appeals to something dark within us as humans — we get some sort of thrill out of revenge, or from knowing that no bad act goes unpunished.

IT RINGS TRUE

A proportion of us really seem to think of the world in Faustian terms, even today. Why does it seem like deals with the devil really do exist? When I think of people who live big lives — often they have a special skill, take lots of drugs and die age 27 — I can imagine they made a deal with the devil for 24 good years in return for the great sacrifice of a hasty death.

Of course, I know no such deal took place. But when it comes to risk-taking behaviour, the very behaviours that were initially rewarded also led to the individual’s downfall. We don’t see all the risk takers who took a risk without the great rewards. But the individuals who do lead Faustian lives stand out.

STAKES ARE HUGE

We find Faustian stories terrifying and alluring in equal measure. These stories are designed to help us understand ourselves, and our own motivations. They also help us to solidify our values.

WE TEND TO THINK WE CAN CHEAT DEATH

One of our most persistent collective wishes is to postpone death. There are always longevity clickbait articles popping up in newsfeeds. Folktales describe many such attempts. Characters rarely succeed, not even in the fantasy world of the fairytale. “Godfather Death,” retold below from a Swedish version, is typical. Although death can’t be cheated longterm, many folktales that describe temporary respites. Is it the temporary respite that we crave?

A poor man with a large family could find no one to be godfather for his latest son. Finally Death appeared, and the poor man chose him, saying: “You make no distinction between high and low.”

Years later, on the godson’s wedding night, Death called him from his bed and took him to a cave where countless candles were burning.

“Whose light is that?” asked the godson, pointing to a candle that was flickering out.

“Your own,” answered the godfather. The godson pleaded with Death to put a new candle in his holder, but the godfather did not answer. The light flickered and went out and the godson fell down dead.

We find from this that you can neither persuade nor cheat Death.

from Thompson, 100 Favorite Folktales, no. 18, type 332

The story of the blacksmith who tricked death (sometimes identified as “the devil”) is one of the most popular folktales in Europe:

The Lord granted a smith three wishes, and the latter chose a pear tree that would detain anyone who climbed into it, an easy chair that would hold anyone who sat in it, and a bag that would imprison anyone who climbed into it. The devil came to get the smith, and the smith invited him to help himself to some fruit from his pear tree. The devil climbed into the tree and was stuck there. The smith would not release him until he promised to give the smith four more years of life. When the time was up the devil returned, but he made the mistake of sitting in the smith’s magic chair, and he had to promise four more years before the smith would release him. On the devil’s third visit, the smith tricked him into his bag, and then beat the bag with his hammer until the devil promised to leave him alone.

Later the smith got to thinking that he had perhaps acted unwisely, and he knocked on the gate of hell to make amends. However the devil would have nothing to do with him, so the smith found his way to heaven. He got there just as St. Peter was letting someone in, and the gate was still ajar. The smith made a rush, and if he didn’t get in, then I don’t know what became of him.

from “The Master-Smith,” type 330 (Asbjørnsen and Moe, East o’ the Sun, p. 105.) For additional variations on this very popular theme see Ashliman, A Guide to Folktales, pp. 73-75

Note how the devil in these tales is not very similar to how we see the Devil depicted in stories today. The devil of traditional religion is cunning, sinister, wicked, and almost as omnipotent as God. But in these folktales he is a fool, and he can be outwitted by a clever, trickster mortal.

This is not an unusual set-up in folktales. In those older stories, even St. Peter is frequently portrayed as a fool. His stupidity also makes Jesus look a lot smarter. (See Godfather Death: Tales of Aarne-Thompson Type 332.) The idea that we can outsmart evil is reassuring, and I imagine this is why audiences enjoyed these folktales so much.

EXAMPLES OF MODERN FAUSTIAN STORIES

You can take my body

You can take my bones

You can take my blood

But not my soul

The story of this song by Rhiannon Giddens centers anyone who has ever had to use their body for someone else’s gain. In this case it is a story of slavery. Slavery itself contains Faustian similarities.

Sometimes the entire plot deviates little from the early Faustian ones. In other stories it’s less obvious.

- The Book of Job — “And Satan answered the Lord, and said, Skin for skin, yea, all that a man hath will he give for his life. But put forth thine hand now, and touch his bone and his flesh, and he will curse thee to thy face. And the Lord said unto Satan, Behold, he is in thine hand; but save his life” (Job 2: 4-6). Job is antithesis to Faust — saintly and completely dedicated to the Lord. Faust is not dedicated to the Lord. He’s all about knowledge rather than faith.

- There are various Grimm tales about deals with the devil. Contained in the first of the Grimm collections is “The Blacksmith and the Devil”. A blacksmith almost hangs himself after losing all his money but a man with a long white beard appears from behind a tree and promises ten years of good life, after which the blacksmith belongs to him. Similar tales include “The Godfather” (Grimm, no. 42) and “Godfather Death” (Grimm, no. 44).

- The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen

- Faust was made for film in 1994 by Jan Svankjajer. Faust is portrayed by actors, puppets and animation in a setting cast in darkness and shadow. Darkness and shadow tend to be common to cinematic Faustian stories.

- The Firm — in exchange for a well-paid job in law, a young law graduate gives his life. Now he’s part of the firm, he’ll never be allowed to leave.

- Silence of the Lambs (1991) —Hannibal Lecter is Faust’s Mephistopheles. He tempts Clarice Starling with greater knowledge in exchange for his participation in evil. Clarice is Faust. She confronts and deals with evil so she can contain it (to stop her private ‘lambs’, from screaming). She learns the lambs will never stop screaming because evil will always be there. Clarice isn’t interested in Hannibal Lecter so much as she’s interested in evil itself, and the evil within all of us, inclining in herself. (For more on this read Film as Religion by John Lyden.)

- Damn Yankees

- Rosemary’s Baby

- The Picture Of Dorian Gray

- Devil’s Advocate

- Paradise Lost of the Justice League (2002) — a children’s cartoon starring caped crusaders. They are able to defeat all them them, until an ancient magician puts all the League under a spell. The only one who can win against Faust is Mephistopheles, who betrays him in the final scene. They all escape with lives intact.

- Thelma & Louise sees main characterThelma finally achieving emotional independence and true freedom, but she must pay the price of death.

- Batman Begins (2005) — Batman is Faust in a cape.

- “The Devil and Daniel Webster” is an American short story by Stephen Vincent Benet, in which a man trades his soul with the devil. In ‘selling soul story’ tradition, this one takes place at a crossroads. Crossroads are highly symbolic. They represent moral dilemmas and major life decisions in general. Sometimes there is no literal crossroads. As a new spin on old tropes, “The Devil and Daniel Webster” contains no cross road in the traditional sense — rather, the story takes place at the meeting of three American state borders: It’s a story they tell in the border country, where Massachusetts joins Vermont and New Hampshire.

- Breaking Bad is a Faustian story. Walter White earns ridiculous amounts of money, but he won’t have enough time on earth to spend it. He’s going to die now.

The Picture of Dorian Gray Full Cast Recording from Librivox

FAUST AND LITERARY MONSTERS

Thomas C. Foster considers Frankenstein a take on the Faustian tale:

We keep getting versions of Faust, from Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus to Goethe’s Faust to Stephen Vincent Benet’s The Devil and Daniel Webster to Damned Yankees to movie versions of Bedazzled (and, of course, Darth Vader’s turn to the Dark Side) to bluesman Robert Johnson’s stories of how he acquired his musical skill in a meeting with a mysterious stranger at a crossroads. The enduring appeal of this cautionary tale suggests how deeply embedded it is in our collective consciousness. Unlike other versions, however, Frankenstein involves no demonic personage offering the damning margin, so the cautionary being is the product (the monster) rather than the source (the devil) of the unholy act. In his deformity he projects the perils of man seeking to play God, perils that, as in other (non comic) versions, consume the power seeker.

How To Read Literature Like A Professor, Thomas C. Foster

THE STORY OF ROBERT JOHNSON

On Netflix right you can find a number of stories about characters making deals, with something unseen and unknown (maybe the devil). Documentary Devil At The Crossroads is about the myth surrounding real life, hugely influential musician called Robert Johnson, who learned guitar so quickly and so well that nobody believed he could have.

In reality, Johnson had large hands, which allowed him to to do things others could not. (This was not the full story, but part of it.)

My own interpretation of the Robert Johnson story goes like this: If you happen to know any musical savants, you won’t be all that surprised about Johnson — someone whose brain is wired for music can learn it quickly. Robert Johnson was denied musical opportunities as a child, partly because he was poor, partly because he was Black. When he was finally given a guitar and a bit of tuition in early adulthood, he was at first ‘not very good’ but then he disappeared. When he returned a year and a half later, his skills had exceeded that of his mentors.

There is a documentary series on Australian TV about child geniuses called Making Child Prodigies. One of the boys featured is a modern Robert Johnson on the electric guitar. What if Callum had been denied access to a guitar until early adulthood? I believe he would’ve picked it up within a year and a half, because that’s how his brain is wired. On YouTube, Callum McPhie’s channel is called The Heavy Metal Kid.

What really strikes me as eerie: Similarities between Robert Johnson and Christopher Marlowe’s experiences in pubs. Marlowe was actually killed in a tavern brawl age 29. No one knows for sure how Robert Johnson died, but he was dead at age 27. He was a well-known troublemaker in pubs.

According to one theory, Johnson was murdered by the jealous husband of a woman with whom he had flirted. In an account by the blues musician Sonny Boy Williamson, Johnson had been flirting with a married woman at a dance, and she gave him a bottle of whiskey poisoned by her husband. When Johnson took the bottle, Williamson knocked it out of his hand, admonishing him to never drink from a bottle that he had not personally seen opened. Johnson replied, “Don’t ever knock a bottle out of my hand.” Soon after, he was offered another (poisoned) bottle and accepted it. Johnson is reported to have begun feeling ill the evening after and had to be helped back to his room in the early morning hours. Over the next three days his condition steadily worsened. Witnesses reported that he died in a convulsive state of severe pain. The musicologist Robert “Mack” McCormick claimed to have tracked down the man who murdered Johnson and to have obtained a confession from him in a personal interview, but he declined to reveal the man’s name.

Wikipedia

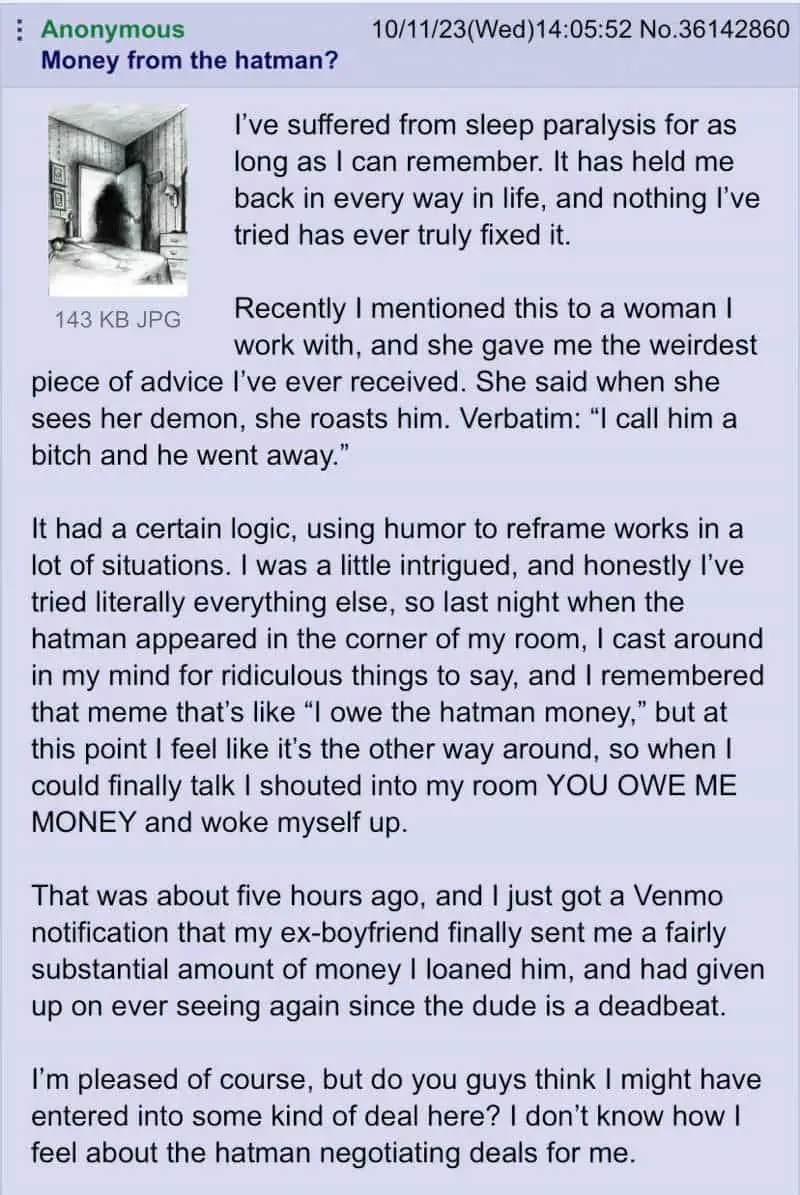

SMALL DEALS WITH THE DEVIL IN OTHERWISE NON-FAUSTIAN STORIES

In her short story “Tableau Vivant”, Robin Black deftly depicts a common thought-pattern: that happiness must be repaid by misfortune. The story is about an older woman who has had a stroke. The story goes into Jean’s backstory:

She could remember [her daughter’s] very first few months, how she had been so little trouble, so docile really, that Jean had endured regular bouts of fear, not only that the baby wasn’t normal—by which she then still meant exceptional—but also that so easy an infancy would be paid for one day, fear that it all evens out somehow, suspicious even then of the deals life might make on our behalf.

Robin Black, “Tableau Vivant”, If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This

How many of us recognise this thought-pattern? Something good happens… but it can never last. Something bad will happen, and that will be a kind of payment for enjoying happiness and good fortune. We are inclined to make cause and effect connections when none are present.

This particular cognitive bias can lead to unhappiness. Problematically, we may be loathe to shuck it off, because it can also provide us with consolation during the lowest times. “Something terrible just happened to me; I’m owed something good.”

Hmm, life hasn’t been very kind to me lately (Well)

Freedom lyrics, from Django Unchained, in which ‘something’ refers to the cognitive bias of subjective validation.

But I suppose it’s a push for moving on (Oh yeah)

In time the sun’s gonna shine on me nicely (One day yeah )

Something tells me good things are coming

And I ain’t gonna not believe

RELATED

The concept of ‘selling one’s soul’ is also behind the ancient practice of ‘sin eating’.

A Life No One Will Remember. A Story You Will Never Forget.

France, 1714: in a moment of desperation, a young woman makes a Faustian bargain to live forever and is cursed to be forgotten by everyone she meets.

Thus begins the extraordinary life of Addie LaRue, and a dazzling adventure that will play out across centuries and continents, across history and art, as a young woman learns how far she will go to leave her mark on the world.

But everything changes when, after nearly 300 years, Addie stumbles across a young man in a hidden bookstore and he remembers her name.

Header photo by Caitlyn Wilson