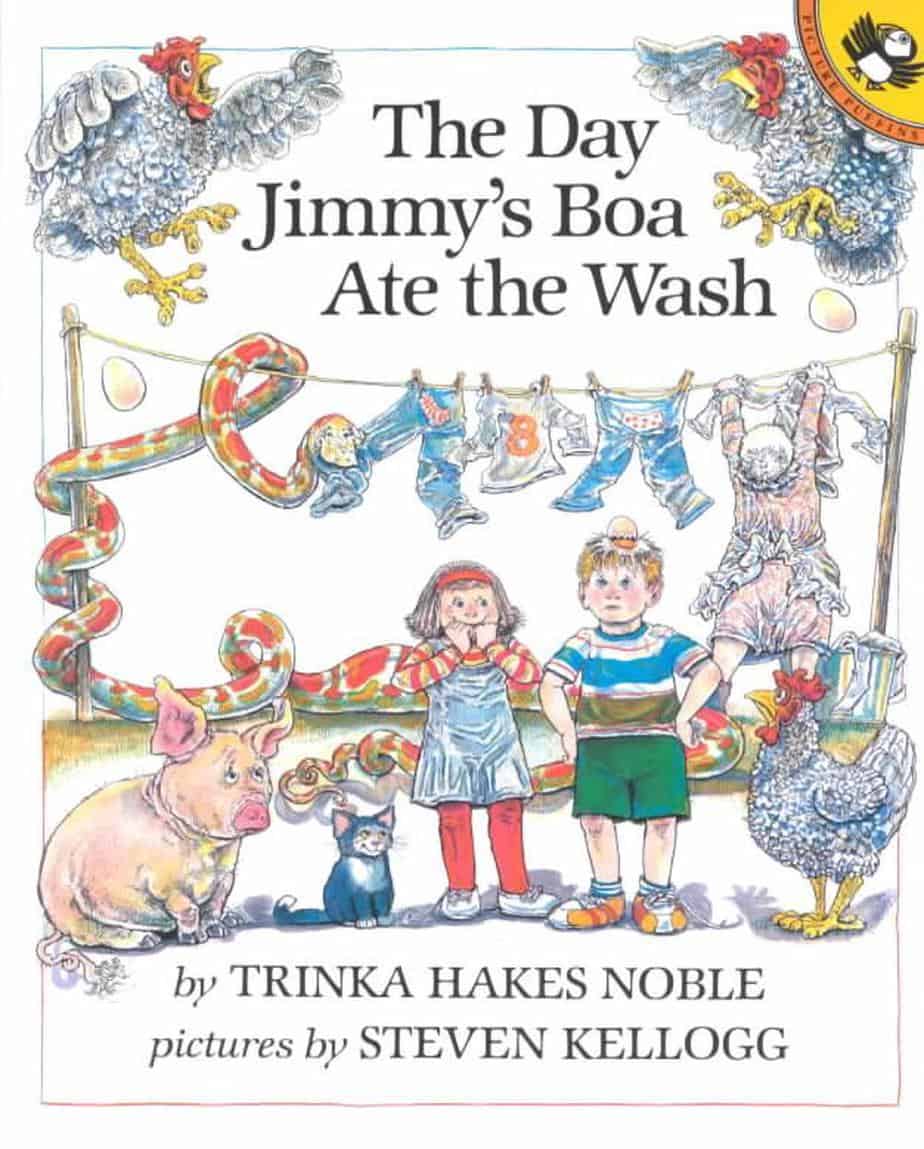

The Day Jimmy’s Boa Ate the Wash (1980) is a carnivalesque, cumulative picture book written by Trinka Hakes Noble and illustrated by Steven Kellogg. This picture book is a great mentor text for the way it handles dialogue visually, and also for the way the ironic distance between text and image expands at the end, leading to a satisfying climax.

NARRATION AND SETTING OF THE DAY JIMMY’S BOA ATE THE WASH

Carnivalesque picture books tend to be centred around the child’s home. This story is an exception because it takes place at a farm, on a class trip. However, the author is using a hypodiegetic narrator in which a girl is indeed safe at home, recounting her wild trip to her mother.

We don’t know if this story is the slightest bit true, and that is part of the beauty of this book. The story comprises entirely dialogue, between mother and daughter. It is so very reminiscent of two childlike traits of conversation:

- hyperbole when recounting events (some might call it lying!)

- the nascent ability for children to recall events, but not as they happened. This girl is unable to guess what the mother can deduce and therefore gives the mother the highlights without explaining how any of the ridiculous situation came about. This gives the storyteller plenty of scope for filling in details in backwards order, leading naturally to a climax.

How reliable is this young narrator? Well, we know she did go to the farm because she brings back a souvenir in the form of a corn cob.

The illustrator makes use of ‘image bubbles’ (with images instead of speech inside them) to show a pre-literate reader who is saying what. These image bubbles start off small (the size of regular speech bubbles) but next the story is ‘exploding’ and the image bubble fills the top half of the page. Now we are fully inside the girl’s story, and the carnivalesque story of her day at the farm fills entire two-page spreads.

CARNIVALESQUE STORY STRUCTURE OF THE DAY JIMMY’S BOA ATE THE WASH

Paratext

Jimmy’s boa constrictor wreaks havoc on the class trip to a farm.

MARKETING COPY OF THE DAY JIMMY’S BOA ATE THE WASH

An Every Child is at home

Even the farm story has a home-like feel. When I talk about ‘home’ in the context of carnivalesque, I mean a safe and familiar setting with an adult authority figure from the real world. In this case the teacher is the mother stand-in; the farm setting is the backyard. The classmates are the siblings.

Importantly, the ‘home’ is a cosy, utopian setting which the child reader can use as safe base while having oodles of fun. This is your classic American storybook farm, with reassuring stacks of hay.

The Every Child wishes to have fun.

There is plenty of conflict between the child peers. At one point the storytellers make use of that old egg in the hair trope so often applied to girls (that’ll learn em for trying to look pretty). We see hair spoilage in Ramona Quimby, Junie B Jones and pretty much every similar middle grade book about a rambunctious girl.

To this non-American, there is also something American-feeling about the ‘pie-in-the-face’ part where the girl gets an egg thrown at her face (also, ouch). But genderwise, this is an effort towards equal opportunity in mischief making. The girls are as playful as the girls.

Appearance of an Ally in Fun

The various farm animals make up the allies in fun.

Disapperanceor backgrounding of the Home authority figure

At this point, the authority figure has usually disappeared. In this case, the teacher is backgrounded. We see her with egg on her skirt and a chicken on her head; she’s powerless against the chaos. She’s clearly trying to conduct a farm visit in the way she’d conduct a classroom lesson, by writing things on the portable blackboard. There is an ironic distance between what the teacher wishes to teach (‘poultry’) and what the children are clearly more interested in (Jimmy’s pet boa constrictor). The double layer of irony here, darkly available to children who already know, is that boa constrictors eat chickens.

Hierarchy is overturned. Fun ensues.

The two page spreads get more and more crowded as the story progresses, with more and more happening.

Fun builds!

In the background, almost like a mountain range, the farmer hangs up washing. This will come in handy later. (Look how much washing she’s doing… I guess she gets plenty of school trips to the farm!) Everything is hyperbolic.

The mother starts filling in some gaps, preparing the reader for the turn.

Peak Fun!

On any given page of a picture book we can say how well the text matches the pictures. When the text says something different from the pictures, we call it ‘ironic distance’. Others call it ‘counterpoint’.

Although the pictures say far more than the text can on any given page of this book, although the girl says her day was ‘kind of dull’, and although there’s an overarching ironic distance between the girl recounting to her mother and what probably actually happened on the school trip, the widest ironic distance is saved for the climax.

The climax is the page where the boa constrictor is making its way along the line of washing, and the girl has no idea what happened to it. She knew everything else until now; suddenly the reader is in audience superior position. We know what the girl does not. This also suggests in a sublte wink, that she’s telling the truth, because if we are seeing what the girl doesn’t know, she can’t possibly be lying about it, right?

“Well, what finally stopped [the chaos?]”, the mother asks. This is a question the storyteller must ask themselves when writing any carnivalesque story for kids, and it is by far the most difficult part of crafting a carnivalesque tale. It’s fun and relatively easy to have your characters run riot; far harder to create a satisfying climax and surprise.

Both of those factors are necessary for a carnivalesque story to work.

Surprise

Jimmy loses his boa as it wends its way through the washing on the line.

In many cases it’s a real fizzer when the publishers give away the climax in the title. But carnivalesque stories play a specific role: they offer safe, imaginative, chaotic fun for young readers whose lives are so proscribed by the authority figures in their lives. The turning point at this part of a carnivalesque tale must be both expected and surprising. The young reader has probably half forgotten the title anyway. Also, I should say, when I imagined a boa constrictor ‘eating the wash’, I didn’t imagine it would play out in that exact way. So it’s still a surprise.

Also, there’s another part to the surprise. Jimmy’s boa has been swapped out for a pig.

Return to the Home state

So although the children have got on the bus to return home, the fun peters rather than splutters out, because that pig that earlier made it onto the school bus comes in handy.

Note: the pigs on the bus were introduced earlier! That’s important. Don’t introduce anything new at the end, same as when writing a transactional essay. Hopefully so much has happened since the pigs on the bus was mentioned that the reader has half forgotten about them.

Extrapolation

The new pet pig creates the suggestion of a circular story, in which the next book in the series will be about the trouble caused by this pig.

“Boy, that sure sounds like a fun class trip,” says the girl’s mother. “Yeah, if you’re the kind of kid who likes class trips to the farm,” replies the girl, while dressed in a space explorer play suit. At first I wondered why the girl was wearing a space suit, but it becomes clear: This kid is interested in outer space, not in earthly adventure. A class trip to a farm would never satisfy this kid no matter what happened there.

SEE ALSO