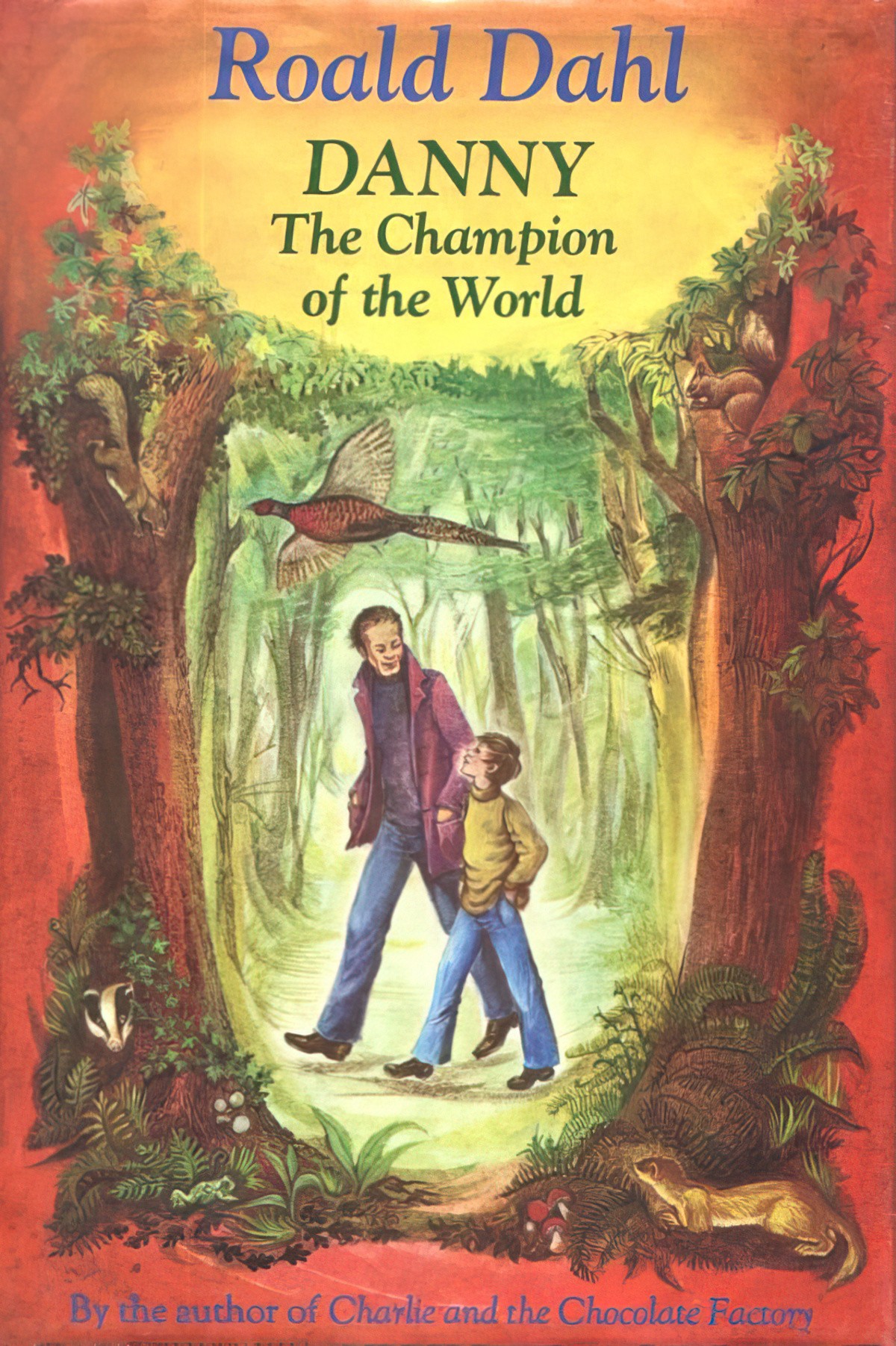

As an English speaking child of the 80s I grew up on a heavy diet of Roald Dahl. Danny The Champion Of The World (1975) stands out in my adult memory my favourite Dahl story, perhaps only bested by the frisson of horror left by The Witches (in which I actually examined my J2 teacher, thinking she might be a witch. Fortunately she didn’t wear gloves, which absolved her.)

I have now, finally, revisited Danny The Champion Of The World as an adult, despite this being one of my favourite childhood reads. Why ‘finally’? I’m loathe to further promote Dahl’s work on the Internet, partly because an entire cottage industry has popped up around the man and the mythology, with teacher resources available, schools full of class sets of his books. My own child’s primary teachers are still teaching Roald Dahl, despite there being many, many better options for a class study.

I also prefer to avoid Dahl because he was a terrible person, and we may be able to put that aside, except his exact brand of terribleness comes through in the text.

Dahl was a vengeful piece of work. God help anyone who got on the guy’s wrong side. In my memory, Danny The Champion of the World was one exception to the revenge plot, but I had completely forgotten the plot. This book is based in realism, but is a revenge plot through and through.

THE REVENGE PLOT

The revenge plot, so I have learned, is a satisfying story to read, and successful with audiences. Compared to other, nuanced forms of story they’re not so hard to plot, either, if you can see the underlying formula. This article makes a case for why the revenge plot is a ‘brilliant choice’ for beginner writers.

- Create a highly empathetic main character/family/group. These characters are underdogs.

- In opposition, create a wholly unempathetic character.

- At the beginning of the story, show readers the thing that would really, really rile the opponent up.

- The opponent does really mean things to the empathetic character/s. For no reason. Pure evil is fine for our purposes. The seven deadly sins come in useful if you’re stuck for how to make the opponent Bad.

- The opponent keeps doing mean things until they almost defeat our empathetic main character/s.

- The main characters now show the audience their trickster attributes, and carry out some kind of heist/plan. They successfully foil the mean opponent who has wronged them.

- The opponent is punished, and the worst thing that could possibly happen to him, happens.

This basic plot describes Danny the Champion of the World, and also describes a great number of Dahl’s stories for children, as well as his short stories for adults. Dahl loved the revenge plot, as he loved revenge in real life. Children’s literature is starting to move past this kind of revenge plot. Punishment as a way to change behaviour has likewise fallen out of fashion (due to behavioural research — punishment doesn’t work). But Dahl has left a strong legacy, and we’re still seeing revenge plots on children’s bestseller lists, e.g. in the work of David Walliams.

I’m mindful of judging creators of art purely by looking at their art. That’s unfair. The author is not the narrator. However, much has been written about Dahl the Man, and this is what Jeremy Treglown wrote about Dahl. This is in relation to Danny The Champion Of The World, in which it seems Dahl tried to create an image of himself as a benevolent ‘friendly giant’, ‘fun’ father in the same way Bill Cosby tried to create an image of himself as a benevolent, wise, fatherly archetype:

Another view of Dahl which he encouraged was as the libertarian father idealized in Danny, the Champion of the World. The book, first published in 1975, mythologizes a father-son relationship of the kind which, in both roles, Dahl had seen shattered. It is also an ode to a newly prevalent condition, that of the single parent, as well as to an old one, the rural outlaw. When Danny—the book’s narrator—was a baby, his father “washed me and fed me and changed my nappies and did all the millions of other things a mother normally does for her child.” Yet this male mother is a traditionally macho, omniscient patriarch, a skilled car mechanic and maker of kites, wildlife expert, storyteller, and defender, who takes Danny’s side against a bullying teacher. He also has a secret. At night he creeps out of their gypsy caravan and goes poaching in the nearby woods.

In essence, it is an expanded version of the ideal of devoted, piratical fatherhood in Fantastic Mr. Fox, and we are clearly meant to read the book as another allegory of Dahl’s own menage. It is dedicated to “the whole family: Pat, Tessa, Theo, Ophelia, Lucy.” The gypsy caravan (on whose roof apples thud with an everyday evocativeness reminiscent of Dahl’s earliest stories) is based on the one still parked in the garden of Gipsy House. The gas station comes from Dahl’s first job; Danny’s teachers are versions of those at St. Peter’s, Weston-super-Mare.

Even the nocturnal poaching had been one of his real hobbies. But when the book was written, in the early 1970s, the sport had developed an additional symbolic meaning for him, signaled by a warning which Danny gives to his readers: “You will learn as you get older, just as I learned that autumn, that no father is perfect. Grown-ups are complicated creatures, full of quirks and secrets … that would probably make you gasp if you know about them.” Such quirks, we are to understand, must be forgiven in both parents and children.

Jeremy Treglown, who wrote a biography of Roald Dahl in the mid nineties.

SETTING OF DANNY THE CHAMPION OF THE WORLD

- PERIOD — Late 60s-early 70s. I deduce between 1963 and 1971. (I based that arithmetic on the narrator’s description of the age of a car.) So much social change happened in that decade, and I do wonder if the father was a hippie, or if he was more conservative type. He could go either way, honestly. Was he also smoking weed out there? Was he wearing bell bottoms? The illustrations of my childhood version were done by Jill Bennett, who has dressed him as a conservative country type. (Quentin Blake later re-drew the illustrations, which I have not sought out.) In this era, ‘gipsy’ was not widely known (or respected) as a slur to describe the Romani and other travelling peoples. Dahl uses it without any thought to that, though unlike many other children’s writers of his era, he is using the gipsy caravan as a symbol of a simple, romanticised era in which no one is tied down. Nesbit and Blyton before him used gypsies as the baddies.

- DURATION — The story opens in iterative mode and, as way to evoke empathy, summarises the narrator’s life from birth until the age of 9. But after the switch to the singulative, the story takes place one summer, within the timeframe it takes to heal a broken leg.

- LOCATION — In the English countryside near a small village. Dahl had a real location from his own life when he imagined this setting. The woods are an exciting place. In fairytale, the woods/forest equals the subconscious, containing all your greatest fears.

- ARENA — The characters travel as far as the estate of the landed gentry.

- MANMADE SPACES — Technology is typical for the era. Not all households own an electric oven or a deep freezer; these are considered middle class luxuries. But at the end of the book, when the father says they’re going to buy these things to roast and freeze pheasants, he magically has the money, which leads me to the conclusion that Danny’s father lives a Spartan existence by choice. I guess he’s the 1960s equivalent of a minimalist. He also displays shades of the guys I see on Doomsday Preppers — fantasies of hunting and living off the land, off the grid, sticking it to the man. He’s a Robin Hood fantasist, because he would only steal from someone horrible and rich.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — A big aristocratic house (which we never see) surrounded by exciting woods where pheasants have been brought in for the purpose of shooting.

- WEATHER — The village is arguably a utopia, or would be if it weren’t for that pesky Mr Hazell. In a children’s book utopia, weather doesn’t get in the way. It would be a whole extra level of misery if it happened to be raining in that hole, and the father ended up with hypothermia. Utopias commonly include apple trees, and Danny is comforted by the plop, plop, plop of the apples falling onto the roof of the caravan. This imagery will be mirrored later as the pheasants fall plop, plop, plop out of the trees. In a utopia, food is never scarce, even if it takes some effort to catch.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — The sleeping pills.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — This is clearly one of those English villages set up by the aristocracy — the landed gentry has a massive castle type place and a whole heap of land. The peasants live nearby, to service the aristocracy. In the earlier days of aristocracy, aristocrats (supposedly) felt the social obligation to care for the peasants around them, in paternalistic fashion. By the 1960s, many of these aristocrats (or nouveau riche moving into these places) and felt no obligation to the surrounding villagers whatsoever.

- THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE — How well does Danny understand his father? There’s some ambiguity about when Danny wrote this autobiography. Has he only just written it (maybe as a 14 year old?) or is he looking back as an adult? If the story happened in the late 1960s and the story was published in 1975, then Danny is writing this as a young adult. He thinks the sun shines out of his Dad. The final sentence of the book is written as if the father is dead, actually. I don’t believe Danny has a handle on the man behind the father, who he continues to idealise, but I’ll write more about that below.

STORY STRUCTURE OF DANNY THE CHAMPION OF THE WORLD

The shape of this book feels almost circular, though circular stories tend to be more domestic and aimed at girls. Also, circular stories tend to cycle through the seasons of a year, whereas this is firmly a summer story.

Dahl was expert in writing stories which you can almost fold in half and create a butterfly pattern with paint. This is more obvious in a shorter story, The Enormous Crocodile. Julia Donaldson uses the same pattern in The Gruffalo. Danny The Champion of the World is nothing like those stories in plot, but in structure, yes.

Dahl uses a trick utilised by Annie Proulx — he brings in the boy’s father, grandfather and greatfather to give the story importance in the great chain of being. Danny feels more important because he is part of a family tradition.

How does the first third of the story mirror the final third? A few examples:

- Victor Hazell is terrified that Danny will put his grubby fingers on his paintwork; Victor Hazell gets his paintwork scratched up by the pheasants (the worst thing happens)

- The apples fall on the roof; the pheasants fall out of the trees (mirrored imagery)

- Each generation of men in this family has come up with his own method of catching pheasants

- The pheasants are depicted as dopey-stoopid; the pheasants are depicted (for a gag) as smart.

- The trout mentioned at the beginning becomes the new focus at the end, suggesting a repeating story.

PARATEXT

The modern marketing copy is unusual for giving away the final sentence of the book:

Danny’s life seems perfect: his home is a gypsy caravan, he’s the youngest car mechanic around, and his best friend is his dad, who never runs out of wonderful stories to tell. And when Danny discovers his father’s secret, he’s off on the adventure of a lifetime. Here’s Roald Dahl’s famous story about a 9-year-old boy, his dad, and a daring and hilarious pheasant-snatching expedition. Just as important, it’s the story of the love between a boy and his father who, in Danny’s own words, is “the most marvelous and exciting father a boy ever had.”

Goodreads

SHORTCOMING

The father is prone to fits of pique, which makes him a Fun Dad, but also a little bit dangerous. This explains why it’s often useful to dispatch with the mother right at the beginning of a story. Mothers (in fiction as in real life) are judged more harshly for up and leaving their kid in the middle of the night, so storytellers prefer to avoid that.

Danny is your Every Boy with a few distinguishing features: By the time the action starts we know he is ingenious, and a problem solver. He can already assemble an engine. We are safe in this kid’s hands. His youthful naivety puts him at a disadvantage in this world of adults, but we can say that of every single child character. What he doesn’t understand at the beginning of the story (nor at the end, in my opinion): The true nature of his father, as an individuated human being. We all have to learn that our parents are people in their own right, and Danny is about to start down that journey.

DESIRE

Danny’s father drives the action, but is stupid enough to fall into a hole and let the child character take over. The father wants the excitement of hunting forbidden pheasant, carrying on the patrilineal tradition of stealing game from the landed gentry.

Danny wants to save his father, and also to prove his worth as a boy of standing in the village.

OPPONENT

Mr Victor Hazell, clearly. The gamekeeper is his henchman who lurks in the woods.

The village policeman turns out to be a false-opponent ally.

Ultimately, this is a story about the opposition between the rich and the poor. The final chapter underscores how poor Danny and his father live, and how generous they are by inviting the doctor and his wife around for dinner. They’ll sit on boxes; they’ll refashion a sheet as a tablecloth (I hope they wash it first). Dahl emphasises the goodness of poverty in the way he does with Charlie (and the Chocolate Factory). Rich people equal greedy and immoral; poor people equal generous and moral.

PLAN

An entire chapter is dedicated to the tricks used to catch the pheasants. Dahl had me wondering if they actually work.

The initial plan is just to catch a few pheasants, but after the father falls down the tiger-trap he gets mad, and now he wants to get even. Like the most compelling of thrillers, this is the main character doubling down on their plan.

But because this is a children’s book, the plan has to come from the child character. It is Danny who comes up with the idea of dosing (poisoning) the pheasants with his father’s unused sleeping pills. Danny doesn’t feel this was his idea, but he is constantly praised for his ingenious idea, hence the moniker ‘Champion of the World’.

During the heist part of the story Dahl makes good use of the Ticking Clock Technique. The sun will be coming up and the gamekeeper will return to catch Danny’s dad. But because this is a kids’ book, Dahl doesn’t cut it too fine. There are still a few hours in which Danny can haul his father out of the hole.

Narrative drive is also improved by the ticking clock that is the pheasant shooting party, just a few days away.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Dahl faced a plotting issue with this story, and how he deals with it is masterful. I don’t think it flies as well today as it did when first published, because contemporary children’s books avoid animal cruelty, and readers are collectively a bit more literate about the environmental damage wreaked when an entire species is culled in one fell swoop. (l know, the whole thing is muddy; these pheasants are an introduced species.)

Here are the problems Dahl would have had to overcome when writing Danny The Champion Of The World:

- The young reader is likely to feel sorry for the pheasants.

- Guns aren’t really okay in children’s stories, despite their widespread use in crime stories (and in actual crime) for adults.

On that first problem, Dahl goes out of his way to justify what Danny and his dad did to those dopey pheasants. First, they’re only asleep for a little while. Second, they inadvertently help the poor pheasants (Hazell’s prisoners) to escape. The pheasants enjoy freedom at the end. But then we feel sorry for the villagers who were looking forward to a pheasant feast, right? So Dahl makes use of the Seven Deadly Sins again, and now he only kills off the greedy ones who pecked more than their fair share. All of this is explained at the end, but you can see how he set it up from the beginning, when Danny points out that some of the pheasants may eat more than one raisin each. The gag at the end about the pheasants supposedly being smart enough to know they’re about to be hunted ties off this entire sequence in masterful fashion.

Now to that second issue, with the guns. These particular guns are not the powerful weapons capable of murdering a person. Near the beginning, Dahl includes a flashback scene in which the father’s dead wife removes bits of pellet from his backside. These are guns used specifically for shooting birds, not people, so this is not a life and death, scary situation for the child reader.

For more on how children’s authors deal with weapons and violence, see my post on what I personally call Chekhov’s Toy Gun.

No doubt about it, Danny The Champion Of The World is a perfectly plotted book. The set up of a utopian life includes just enough detail to engage our interest, and includes information we’ll need for a circular ending.

In no time at all we are plunged into the action, and the nine-year-old driving a car in the dead of night is the resonant imagery from my childhood reading. I wonder if that’s shared by other readers. I do think that a child in control of a vehicle is a great trope in storytelling for children because it is terrifying to be that much in charge but also thrilling.

DIE WUNDERFAHRT (1929) Sándor Bortnyik. (If you’re going to use the child drives a vehicle trope, do make sure you give the girls a turn at the wheel!)

Another image, which I suspect is meant to be the stand-out resonant imagery: The pheasants flying out of the baby carriage. I had completely forgotten about that.

ANAGNORISIS

This story takes place over a few weeks one summer so the character arc from childhood to maturation isn’t large enough to count as a coming-of-age story, but we can call it a Entwicklungsroman, since Danny goes some way from childhood towards adulthood.

Danny’s realisation: That adults are real people. Ironically, Danny realises this about the police officer, who he is initially afraid of when driving at night as a nine-year-old, but who he later learns is ‘one of the ordinary folk’, and not at all averse to a taste of stolen pheasant meat. Dahl puts this revelation right there on the page. But he doesn’t really truly learn this about his own father, who he continues to idealise. He learns that his father has night secrets, but this doesn’t help him to see his father’s flaws.

The revelation that takes place slowly, in the third section of the book: Although Danny felt entirely alone with his father in crime, the entire village is in on the pheasant thing, even the most upstanding of them. The Vicar’s wife is the pinnacle example of someone who looks like she’d never be involved in a plan like this, but who is in fact functioning as the hookup, distributing stolen pheasants to villagers. Dahl presents this as a reveal rather than as a character revelation. (A reveal is a writing technique, between storyteller and audience.)

NEW SITUATION

Okay, so the last sentence is almost identical to how E.B. White ended Charlotte’s Web, and I admit they both affect me deeply:

What I have been trying so hard to tell you all along is simply that my father, without the slightest doubt, was the most marvellous and exciting father any boy ever had.

Danny The Champion of the World, Roald Dahl

It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

Charlotte’s Web, E.B. White

The difference is that we know Charlotte is dead. Why is Dahl’s narrator writing about his father in past tense? (I’m worried about those manic episodes, most often cycling with periods of depression.) Fathers don’t stop being fathers simply because the boy is a man now.

Anyway, in my head the father is dead. Sorry. Um, and that’s why Danny is writing this novel-length eulogy. Eulogies are by their nature complimentary, and leave out all the rubbish bits about a human.

Dahl ends the book with a Perrault-esque, partly jesting plea to readers:

A message for children who have read this book: When you grow up and have children of your own, do please remember something important: A stodgy parent is no fun at all. What a child wants and deserves is a parent who is sparky!

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Over the course of that summer he was nine, Danny did learn a few true things about his father. Namely, his father has his own secret life that happens at night. I’m sure psychoanalysts could go on at length about that, and the particular horror we all experience when we learn how we were made. But the father remains perfect in Danny’s eyes. He only becomes more perfect over the course of the story; his imperfections make him a fun dad.

Is he, though?

Here’s the rub. A ‘fun parent’ as written for kids, enjoyed by kids, comes across as a guy experiencing manic episodes to adults. I don’t believe this is an ideological problem; that’s simply how this father strikes me as an adult reader.

Another parent who seems problematic to my adult self is Lorelai Gilmore of Gilmore girls, overly involved in her only daughter’s life, unpartnered herself, unwittingly involving the child in her own struggles. When the child starts to feel the burden of their parent’s shared issues, psychologists call this emotional or covert incest. (It’s not sexual.) It can cause a lot of harm. However, the teenage audience finds Lorelai the elder a fantasy version of the young, cool parents who is also a friend.

Danny’s father does eventually send him to school, even though the law requires it. Once Danny gets to school, he doesn’t like how the teacher is treating his son. Fair enough, but what was really going on? (Dahl doesn’t show much love for teachers, Miss Honey excepted.)

The father schools Danny up as a mechanic at home, separated from the wider world, and tells him they’re equals now. Danny has no same age friends mentioned on the page. The father relies upon his son to save him in the dead of night. There’s no real moral dilemma of the sort child characters regularly face in stories; saving his father is the worst best choice. It’s not really a choice at all, because Danny’s father is all he has in the world. This is the enduring problem with these types of parent/child relationships; the child has no real choice in action driven by the parent.

RESONANCE

The middle grade novel continues to be studied in schools and read by today’s child readers. Many people continue to remember this book as a ‘standout’ exception to Dahl’s children’s literature oeuvre.

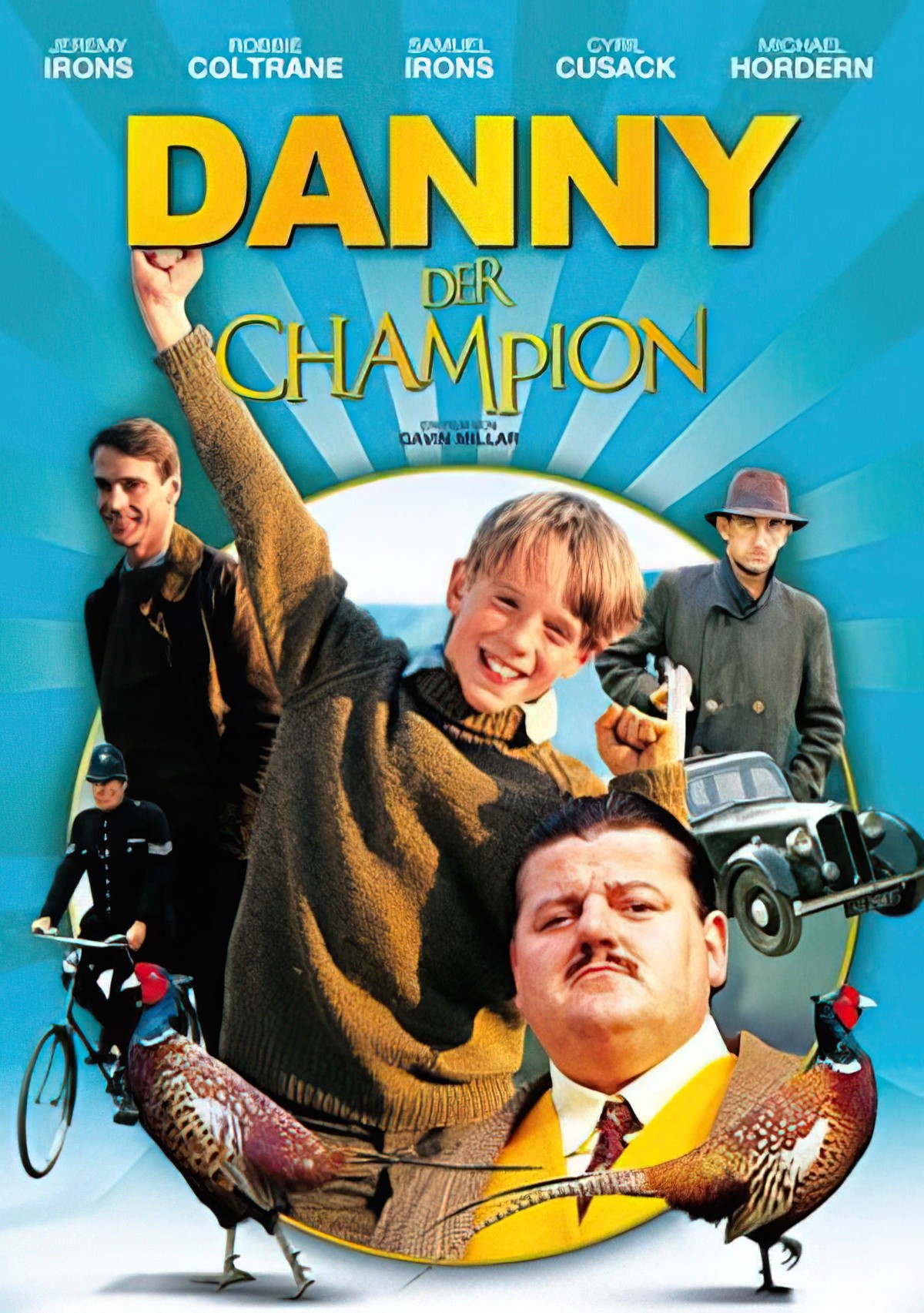

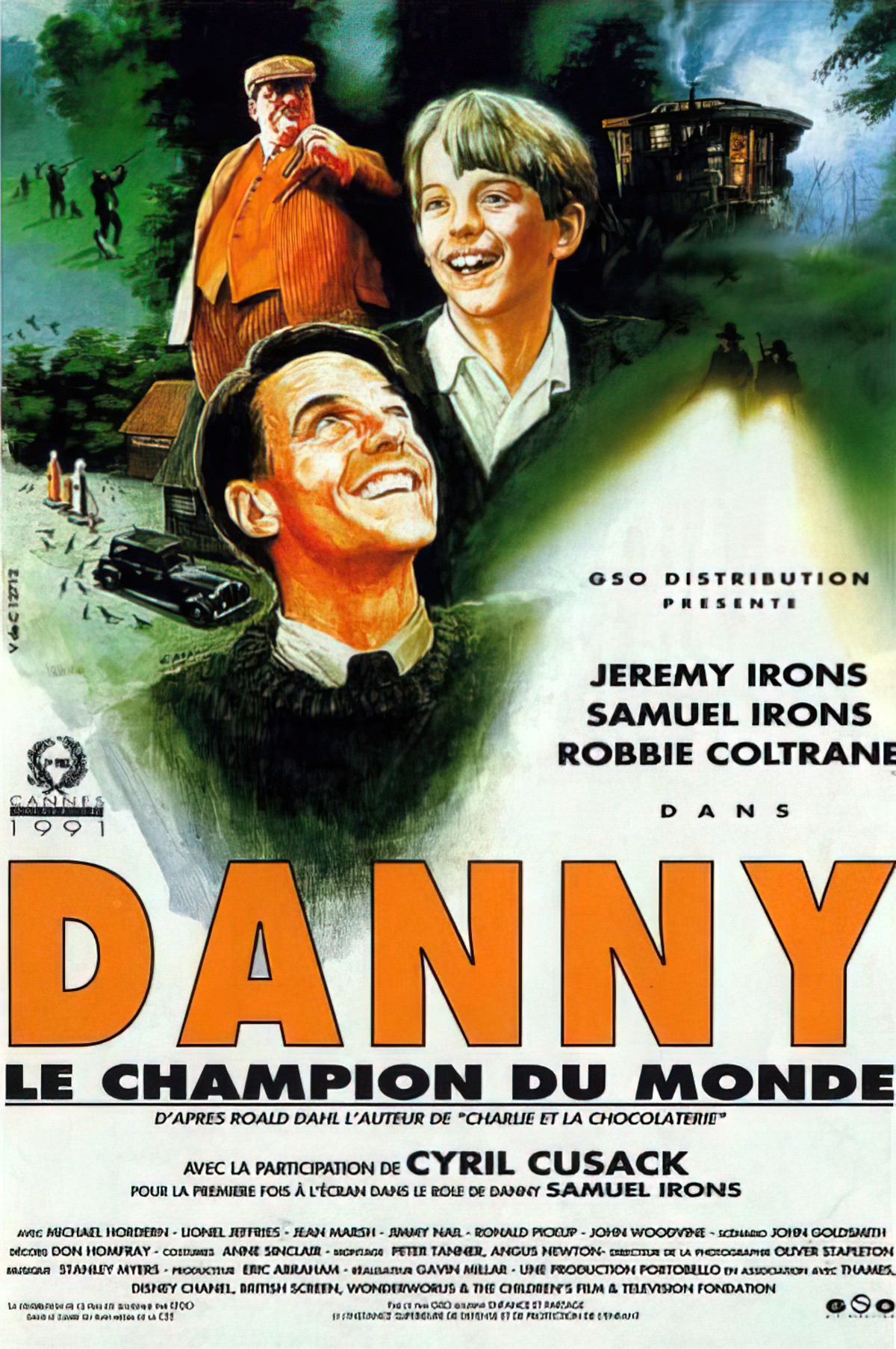

There is a 1989 film adaptation of this book, but it looks to be similar to the tone of Matilda, when I’d hope for something more like Breaking Bad. It’s set in the 1950s, perhaps because adults like to imagine the 1950s as a cosy utopia. It is not set when the book is actually set.

Robbie Coltrane is the only well-cast actor here, in my opinion. As Betsy Bird said of the book in relation to the film adaptation: “Known far and wide as the non-goofy Dahl novel, Danny was so much sweeter and lighter than I would have expected (and did a good job of erasing the made-for-tv movie I saw years ago out of my head).”

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Danny The Champion Of The World at Wikipedia

Header painting: Archibald Thorburn, naturalist illustrator – Pheasants