**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“Dance of the Happy Shades” is the titular short story of Alice Munro’s first collection, first published in 1968.

Neologism to tuck away for later: “sophisticated prudery”.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES”?

An emotionally astute and very observant adolescent girl is required to accompany her mother to an embarrassing recital with the elderly, unfortunate-looking spinster teacher whose spinster sister is recently bedridden due to a stroke.

The story is told via the slightly baffled viewpoint of the girl, who is required to recite a tune on the piano at these embarrassing annual events. The spinsters have recently moved from a small house to an even smaller one. Although adolescents are are renowned for their embarrassment, it is actually the girl’s mother who is affected by extreme cringe.

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara chats with journalist and editor Melissa Dahl about her new book, “Cringeworthy: A Theory of Awkwardness.” They talk about what makes us shudder, from the sound of our own voices to the prospect of starting a conversation with strangers on the New York City subway.

Cringeworthy w/ Melissa Dahl

For one thing, the spinster music teacher has clearly gone beyond her means in providing a lavish afternoon tea, which presently sits flyblown and wholly inedible on the table. The living area is unbearably hot. Nearby, a woman with an unpleasant odour leans in and starts gossiping quietly about their hostess.

As if things can’t any worse, in traipse the children from the local special school. What are the ‘idiots’ doing here, among the upwardly aspiring middle class who diligently ensure their middle-class children are afforded every opportunity, including a musical education?

Surprise surprise, one of the special girls is actually very good at the piano. Better than the ‘normal’ children, in fact, since the piano teacher never corrects anyone or tells them to do better. This girl with the white hair plays a song called “Dance of the Happy Shades” on the piano.

The meaning of this song is translated but never explained. Our adolescent narrator notes that her teacher’s expression shows not an ounce of pride or surprise. She believes children to be wholly capable of their own kind of genius, and in teaching music to the appreciative children with learning difficulties, she has not been proven wrong.

THE REAL LIFE STORY OF SUSAN BOYLE

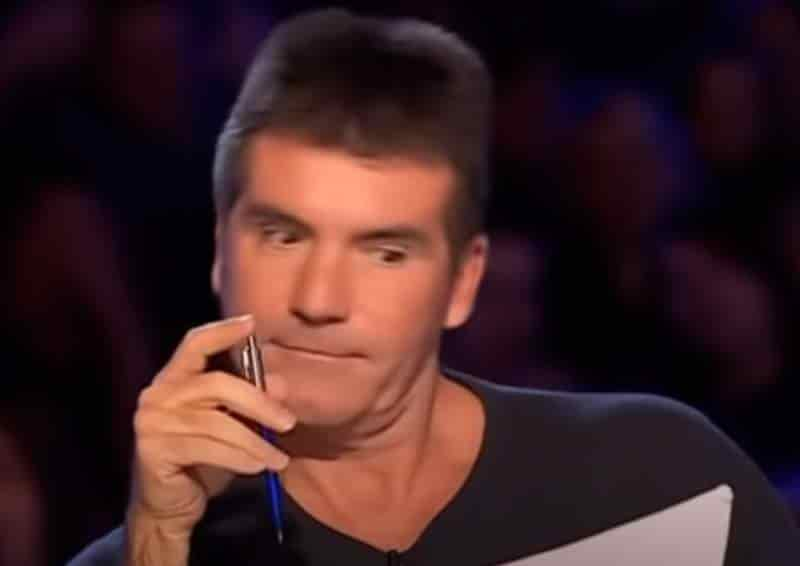

In case you haven’t heard of Susan Boyle: In 2009, unknown, middle-aged Scottish woman had the audacity to enter the third season of Britain’s Got Talent. This was the first time she had sung since her beloved mother died. She’d been one of nine children. She’d never left the four-bedroom family home, and cared for her mother in her old-age. Susan also worked as a church volunteer, and had already given singing as a career a good shot, using all of her savings to cut a CD. Due to lack of publicity rather than lack of talent, the CD sold barely any copies.

Finally Susan made it onto the stage of Britain’s Got Talent, where she presented her wholly unmarketable 47-year-old body to a mean-spirited panel of judges and an audience who jeered before she’d even opened her mouth. Since contestants are advised by fashion experts as a matter of course, it was clearly a choice to push Susan out onto stage wearing shoes that are too light, stockings too dark, and an ill-fitting dress. The humiliation to stardom arc was all part of the arc.

When asked to introduce herself, Susan told the judges — clearly reaching far above her station — that she would love to be a professional singer.

“And why hasn’t it worked out so far, Susan?”

“I’ve never been given the chance before, but here’s hoping it’ll change.”

“Okay and who’d you like to be as successful as.”

“Elaine Paige.”

She’d love to sing for an audience like Elaine Paige. Elaine Paige? Beautiful Elaine Paige with the beautiful voice? Now the audience really started to wonder if this woman was right in the head.

But when Susan started singing, she did sound like Elaine Paige. She did! The audience gasped. She ended up placing second that year, though she was an audience favourite all along.

Catapulted to sudden stardom, Susan did become a professional singer. She did record an album, and made five million pounds the following year. She was able to purchase the four bedroom family house where she had lived with her mother. But now the press hounded her. She could no longer live semi-anonymously in her small village. As many people would, she started to struggle, and has subsequently received an autism diagnosis. She has since produced more albums, and performs at big ticket events where she comes alive on stage with the confidence of a veteran performer.

In some ways, Susan Boyle is the real life version of Alice Munro’s girl with the white hair, producing beautiful music against all expectation, as if musical ability and appreciation (entirely auditory experiences) correspond to looks or to neurotypicality.

Mismatched Women: The Siren’s Song Through the Machine

Jennifer Fleeger‘s Mismatched Women: The Siren’s Song Through the Machine (Oxford University Press, 2014) tells the story of women in film and their representation as aberrations, but also as moments of emancipation and agency. Fleeger’s book discusses exceptional voices such as Kate Smith, known as the First Lady of Radio; Deanna Durbin, whose soprano voice allegedly saved Universal Studios from bankruptcy, Susan Boyle the woman who shocked Britain’s Got Talent jury and public to the point of tears, amongst many others. Fleeger’s approach broadens the traditionally cinematic context of feminist psychoanalytic film theory to account for literary, animated, televisual, and virtual influences.

New Books Network

SECONDHAND EMBARRASSMENT

Some of those facial expressions in anticipation of Susan Boyle’s suspected warbling were probably due to a psychological phenomenon we call ‘secondhand embarrassment’, also known as ‘vicarious embarrassment’, ‘Spanish shame’ or ‘Fremdschämen’ (in German, of course).

- Vicarious embarrassment, is an interpersonal and painful emotion experienced on behalf of others’ blunders and pratfalls.

- The same brain regions have also been implicated when we share others’ physical pain, where they help us to feel the harm to another’s body.

- The closer you are to someone the stronger your affective ties are, and the more likely you are to feel embarrassment on their part.

- Concerns about your own social image significantly contribute to feeling secondhand embarrassment on the part of a friend or family member.

- Some people are highly empathetic and cringe even when watching somebody embarrass themselves in a movie or on TV. Even going to an open-mic comedy night or to karaoke at the pub can be too much for such people. Cringe comedy is definitely out. (The roast section of Ru Paul’s Drag Race and competitions like Britain’s Got Talent are also too much.)

- It can cause physical symptoms in the onlooker such as sweating or blushing.

- Vicarious embarrassment is actually painful. This pain is known as ‘social pain’.

- As well as high levels of empathy, the person experiencing vicarious embarrassment must also be aware of which social rules are being broken.

- Not everyone feels this. In contrast, some people revel in watching someone else embarrass themselves. Cringe comedy is made for them.

Alice Munro has populated the recital with characters who sit at different places on the spectrum of vicarious embarrassment.

The observant daughter seems somewhat detached as our narrator, but I put it to you that she is the most empathetic. She is noticing every detail of the hot afternoon, not to revel in it, but to process the aspect of human nature which has just been revealed.

Her mother is mostly angry that her friend has piked out, leaving her alone with people she considers beneath her. I therefore feel she has very little empathy for the music teacher. But she does understand full well which social etiquette has been broken.

By contrast, we have the woman who leans in to gossip about their hostess, who appears to be someone who revels in someone else’s discomfort.

Then there’s the hostess herself. Alice Munro doesn’t give us a chance to know what she thinks or feels. Everything is left to interpretation and filling in the gaps. But it would appear that the music teacher is the inverse of the angry mother. She has great empathy for others, but little understanding of social etiquette. She has gone out of her way to try and make the afternoon pleasant, and has put much time, resources and effort into the spread of food, only to leave it out in the heat and neglect to keep flies away.

It is these women who become society’s outcasts. You don’t become an outcast for lack of empathy, but for failing to pick up the subtle, unwritten social rules which others appear to pick up so effortlessly.

WHAT IS THE MEANING OF “DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES”?

This piece is from Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Italian opera Orfeo ed Eurydice (Vienna, 1762), based on the Greek myth of Orpheus, whose wife Eurydice dies. That’s what you get when you’re a beautiful woman and you wander through the forest with nymphs. She was chased by a predator shepherd. (This is uncomfortably close to the true crime which happened in Melbourne to a young woman walking home through Prince’s Park in 2018 after a night-time gig as a comedian. Her name was Eurydice Dixon.)

In other versions of the myth, Eurydice was simply dancing with nymphs and got bitten by a snake or something. No male predator.

This historically significant opera is a musical representation of his immense grief. Orpheus replays memories of their time together and the final moments before she dies.

He decides to venture to The Underworld to bring Eurydice back. He is able to charm the three-headed dog who guards the gates by using his musical abilities. (His dad, Apollo, taught him how to play the lyre.) Finally he reaches Hades, god of the underworld, and his wife Persephone.

Hades let Orpheus take Eurydice back home from the Underworld under one very weird condition: She would have to walk behind him and he would not be allowed to look back at her. But he couldn’t hear footsteps. Had the gods fooled him? They were almost out of the Underworld when Orpheus looked back. This sent her back to Hades forever. (Eurydice isn’t told any of this because women are told nothing about supernatural messages cf. Eve in the Garden of Eden. She figures her husband doesn’t really love her, since he can’t bear to look at her.)

Unfortunately for Orpheus, there’s this other rule where you can’t enter Hades more than once if you’re still alive.

By one version of the myth, Orpheus was killed by beasts. However! His head remained attached to his body, which is nice. The head was still able to sing while floating in the water, eventually washing up on the island of Lesbos. There are other versions, but I figure that one’s the most likely, don’t you?

If you study the night sky you’ll see the lyre of Orpheus as a constellation. Meanwhile, the Muses have saved his head. It makes for a good talking point at parties, I guess? Orpheus enchants everyone with his melodies.

But Gluck gave Orpheus and Persephone a happier ending. Orpheus plans to kill himself to join Eurydice in Hades. But Amore intervenes and instead of Orpheus joining Eurydice in Hades, Eurydice is brought back to life. This was a reward for Orpheus’ continued love.

WHAT’S THE CONNECTION TO ALICE MUNRO’S “DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES”?

Let’s talk about the paradise in Hades, according to the Ancient Greeks.

According to Greek mythology, the Underworld comprises a number of different territories. One of those territories is known as the Elysian Fields, the Elysian Plains or Elysium. Initially it was a separate place from Hades, but gradually became more integrated.

The Elysian Fields are a very pleasant place, a utopia, in fact. There are gentle streams, shady parks. You get to do athletics and music all day (great for the jocks and the theatre kids — hopefully P.E. isn’t compulsory).

Here’s how Homer describes it in epic poem “The Odyssey”:

…life is easiest for men. No snow is there, nor heavy storm, nor ever rain, but ever does Ocean send up blasts of the shrill-blowing West Wind that they may give cooling to men.

Homer, Odyssey (4.560–565)

Paradise has always been a great recruitment tool for cults. It helps with the gamification of religion. Originally, you could only enter this place if you were related to the gods but eventually followers were told they could enter the Elysian part of Hades if they were chosen by the gods. Obviously this was a very helpful recruitment tool because now all people had to do was work hard to impress and voila, paradise forever. Work hard now so that in the Elysian Fields you won’t have to… and so on.

Okay, so the hot, close, fly-blown house of Miss Marsalles is nothing like paradise. She’s even got a bedridden sister in the back room, close to death after suffering a massive stroke. Sure, there’s music, but this is hardly Elysium.

But the Elysium of Gluck’s opera is an Other, different place, separate from either life or death. It is a kind of hellscape. But there’s also a freedom which comes from being Othered. These places are Other because of their place or time or because characters defy the accepted social order of the community.

Alice Munro has written of Othered characters in their “other countries” across many of her short stories, starting with a very early example:

- In September 1955 the Canadian Forum published one of Alice Munro’s earliest stories, literally called “At The Other Place”. (This story isn’t easy to find as it’s not included in any bound collections.) She published this as Alice Laidlaw. This was the first time she used what some have called ‘confiding first person narration’. In this story, a family who lives on a remote farm makes periodic trips to a very different sort of farm. Anyway, this story also marked the beginning of a long fascination with characters who live in a place which is separate from the mainstream, in that “other country”.

- In “Walker Brothers Cowboy” (1968) a travelling salesman takes his children off-piste to visit a friend/lover from his past. The observant adolescent daughter learns that her father had a whole Other life before she turned up. The father impresses the magnitude of time upon her by teaching her the Big History of the geography around Lake Huron.

- In “Miles City, Montana” (1985) a young family travel across Canada (Vancouver to Toronto), but they dip down into the USA to take a fresh route, hoping to see new things, to shake themselves out of routine.

In short, the hell that is Miss Marsalles’ house is also an Other Country, where she embraces children who are Othered (due to their intellectual disabilities), and where she creates for herself an Elysium on Earth, full of beautiful music where everyone is accepted. Meanwhile, the mothers remain bound by their small, suburban, upwardly-aspiring lives, never really enjoying anything because they can’t see how to create joy.

Also, it would seem Alice Munro has given Miss Marsalles her happy ending, as Gluck gave Orpheus and Eurydice theirs.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

Two other short stories featuring a socially ostracised character who attempts a cringe-worthy social connection by giving gifts in a way that misses the mark, but elicits much empathy from a empathetic narrator:

“A Beautiful Nature” by Janet Frame

Find this story in The Lagoon and Other Stories (1951). I find the story of Edgar the most moving narrative in this collection. Edgar is a boarder who doesn’t seem to have any friends, but he spends a lot of time writing personalised cards at Christmas. One year he is laid off, through no fault of his own. The mercenary factory owner has fired him right before Christmas. But still Edgar hands out his cards. The women find him an eccentric figure of fun, but their relationship to Edgar is nuanced, because these motherly women are also the most accepting of him. Readers are invited to see Edgar’s humanity and witness his loneliness.

“FUN WITH A STRANGER” BY RICHARD YATES

This American short story dates from 1962, nearer the time Alice Munro was crafting this collection. Again we have a spinster teacher who appears to have no life outside school. How do we know? Her extreme awkwardness. Even her young charges understand how strange their spinster teacher is. The teacher attempts some sort of connection on the last day of the year, but gets it horribly wrong.

Find “Fun With A Stranger” in Eleven Kinds of Loneliness by Richard Yates.

THE UNEXPECTED TALENT TROPE

I’ve searched TV Tropes and I can’t find an exact fit to describe a trope where a designated “stupid” character unexpectedly reveals a high-level skill.

Another example comes from Breaking Bad. Skinny Pete is a hapless minor drug addict who has never grown up since high school. We see him talk all kinds of nonsense when he is high.

But when Walt and Jessie send Skinny Pete with Badger to buy equipment at a music store, Skinny Pete is taken by an electric keyboard and is revealed to be an expert pianist. Actor Charles Baker said he worked for weeks on the piece to make it perfect. But within the world of Breaking Bad, we are to believe the character has a natural talent, and we are reminded against hasty judgment.

DANCE OF THE HAPPY SHADES (1968)

- “Walker Brothers Cowboy” — A woman looks back at her 1930s childhood. Her family has 2 or 3 months earlier lost the family fox farm and moved to a small town on the edge of Lake Huron, where the father has started a new job as a door-to-door salesman. Meanwhile, the mother sinks into a depressive state. One day, the father takes the narrator and her younger brother on a ride, where he visits an old friend/lover. The daughter learns that her father had another sort of life once.

- “The Shining Houses” — In a new neighbourhood, many houses have been built next to an old one. The owner of the older house, Mrs. Fullerton, does not take care of her property to the extent that the owners of the new houses would like. They conspire to get rid of the old poultry-farming witch. Only our narrator seems conflicted.

- “Images” — A little girl is the narrator of this double character study: A second cousin who came to take care of the household while her own mother was sick, and a man with a psychotic mental illness who lived alone in the woods. After meeting the man in the woods, the little girl learns not to be afraid of the woman who has infiltrated the household to take care of them all.

- “Thanks for the Ride” — This story is written with the viewpoint character of a young man. He has just finished school and is out with his older cousin with the purpose of losing his virginity. Together they pick up some ‘loose’ girls. The whole experience is perfunctory and defamiliarizing.

- “The Office” — A housewife decides to improve her life by carving out some time for herself to pursue her passion of writing. So she rents a room above a hair salon and drugstore. But the landlord won’t leave her in peace, deeming her time his.

- “An Ounce of Cure” — A young teenager is pining after a boy who dumped her months ago for another girl. She can barely think of anything else. One night she is babysitting when she spies three bottles of liquor on the bench. She accidentally gets very drunk and very caught out. Her reputation is ruined. But as an older woman looking back on this time, she is glad it happened.

- “The Time of Death” — A mother who lives in one of the squalid cottages on the edge of town has lost a child in a terrible accident. The village gathers round, but how genuine are they in their grief?

- “Day of the Butterfly” — Two girls at a primary school are ostracised. One is the narrator, now grown, ostracised for being an out-of-towner who doesn’t wear the right clothes. The other is more ostracised still, because her parents are immigrants, because she smells like rotting fruit, and because her brother needs her to accompany him to the toilet. When this girl is dying in hospital from child leukemia, the young narrator is filled with inexplicable grief. It is now too late to be a real friend to this outcast, and anything she does in kindness will feel empty and pointless.

- “Boys and Girls” — An outdoorsy farm girl loves helping her father on the fox farm but realises she’ll very soon be required to go indoors to help her mother with domestic work. In contrast, her younger brother, far less conscientious, will be allowed to stay outside and work with the animals, enfolded and welcomed into the masculine world.

- “Postcard” — A woman around the age of 30 has been seeing a man for years. They’re long-term partners. The reason they haven’t married: He’s waiting for his mother to die. His mother wouldn’t approve of him marrying the narrator, we deduce because of the wealth disparity. Unfortunately for the narrator (Helen), turns out the guy never intended to marry her anyway. He sends her a postcard from Florida telling her how he’s having such a good time. Next minute, Helen’s best friend is round to break the bad news: It’s been published in the paper, the lover is getting married to someone else after all this time. The weasel didn’t have the gumption to let Helen know. So she goes round to his house, stands outside and expresses her grief in a very vocal way.

- “Red Dress—1946” — A thirteen-year-old girl’s first ball. Her mother sews a red dress with a princess neckline. Suddenly she looks much older. She barely recognises herself in the mirror, and longs for childhood again. Almost all the girls around her are obsessively interested in boys. Everyone, that is, except one other girl who says she despises boys, and plans to support herself by working as a P.E. teacher. But by aligning herself with this queer girl, our thirteen-year-old risks much. What will she do? Will she take up the offer of friendship?

- “Sunday Afternoon” — Seventeen-year-old Alva has recently finished high school and started working as a maid for the mega-wealthy Gannetts. Today they are hosting a party at their mansion and Alva must navigate a delicate social situation: They want her to feel part of the family, but what does that mean, exactly, when you’re actually the paid help? Alva must also navigate the men who enter the house, several of whom express sexual interest in her. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill, predictable young-woman-is-seduced storyline, but Alice Munro keeps readers in audience superior position as we watch with bated breath what happens to Alva in this big, lonely island of a house. We’re left to deduce most of it.

- “A Trip to the Coast” — An eleven-year-old girl called May lives with her mother and grandmother (mostly her grandmother) in a general store in a three-house township. There’s nothing to do in this one horse town. But today she’s looking forward to same-age company. However, the “company” is a total let-down, and so her grandmother, for the first time ever, suggests the two of them take a trip to the coast. But then another visitor comes. A customer who declares himself an amateur hypnotist. This story ends on a cliff hanger, and I don’t believe Munro has given us enough of a symbolic layer to fill in the gaps for ourselves. I believe we’re supposed to feel exactly as unmoored as eleven-year-old May, waiting out front of the store in the rain.

- “The Peace of Utrecht” — Numerous critics and scholars consider this story the jewel of the crown of Munro’s first collection. Considering that, it’s baffling why it doesn’t make it into more Selected and Collection volumes. It’s certainly the most overtly personal of Munro’s early stories, and she has said in interview that this one changed the way she wrote. Until writing “The Peace of Utrecht” she’d written to be a writer. Now she wrote because she knew only she could write this story. The biographical relevancy: young Alice Munro cared for her mother over many years as her mother lived, then died, with Parkinson’s disease.

- “Dance of the Happy Shades“