‘Cute’ describes something attractive in a pleasing, nonthreatening way. Things that are small or young are often described as cute: babies, fluffy puppies with big eyes, squishy toys. Cute things are easy to like.

Creepiness in Art and Storytelling.

When the word [cute] first appeared in English in 1731, it was a shortened form of acute, the adjective meaning “shrewd,” “keen,” or “clever.” It even had its own opening apostrophe—’cute—to let you know it had been clipped.

The Totally Adorable History of Cute by Katy Waldman

Can you tell us more about “cute” and how it relates to these women who are “rushing”? (Bama rush = the University of Alabama’s sorority recruitment events.)

To be cute is to not be sexually powerful. So it is to be attractive in a way that again comes back to men and the male gaze. To be non-threatening.

I watch those videos through a lens of ‘Who is this made for’? Like, who is the audience? That emphasis on cuteness — the outfits, the diminutive language, the colour palette even, the dance routines — so much of it was so obviously about not being seen as sexually powerful, which of course is a certain type of femininity which is meant to be consumed but not owned by the women themselves. Because when you’re sexually powerful you’re a mature woman. That has always been seen as a threat to the male gaze because it shifts the orientation from ‘What do men want?’ to ‘What do women want?’ Women’s pleasure, women’s desire. And so that emphasis on ‘cute’ … yes, it may be age appropriate — these are young women — but emphasis on ‘women’. The male counterparts don’t have that emphasis on something that minimises them. There’s no male equivalent of ‘cute’.

“The Bama Rush to Trad Wife Pipeline”, Tressie McMillan Cottom, The Waves podcast, Thursday 7 September 2023

The Power of Cute by Simon May (2019)

What does “cute” mean, as a sensibility and style? Why is it so pervasive? Is it all infantile fluff, or is there something more uncanny and even menacing going on—in a light-hearted way?

We usually see the cute as merely diminutive, harmless, and helpless. May challenges this prevailing perspective, investigating everything from Mickey Mouse to Kim Jong-il to argue that cuteness is not restricted to such sweet qualities but also beguiles us by transforming or distorting them into something of playfully indeterminate power, gender, age, morality, and even species. May grapples with cuteness’s dark and unpindownable side—unnerving, artful, knowing, apprehensive—elements that have fascinated since ancient times through mythical figures, especially hybrids like the hermaphrodite and the sphinx. He argues that cuteness is an addictive antidote to today’s pressured expectations of knowing our purpose, being in charge, and appearing predictable, transparent, and sincere. Instead, it frivolously expresses the uncertainty that these norms deny: the ineliminable uncertainty of who we are; of how much we can control and know; of who, in our relations with others, really has power; indeed, of the very value and purpose of power.

Notes below are from Simon May, British philosopher, speaking on the “Totes Adorbs” episode of the Smarty Pants podcast and on the “Kitsch — Cute” episode of Thinking Allowed.

- Cuteness as we know it today wasn’t a thing before WW2, and it really only took off in the 1980s, at which point it swept the world.

- Cuteness is commercially huge: Mickey Mouse (the updated version), E.T., Hello Kitty, cute dinosaurs in The Land Before Time, to today’s emojis.

- There’s another kind of cute which is more interesting to many people: An uncanny, hybrid character which is somehow deformed or hobbled. (Note: Hello Kitty — originally a little girl, not a cat — has no mouth and no voice. That should be creepy, right?)

- Our world is fascinated by indeterminacy. Simon May uses the word ‘unpindownability’ when describing the essence of ‘cute’. Clear categories of yore (male/female, child/adult, human/animal) are breaking down. Trans and non-binary genders are now in people’s consciousness. The child is thought to be always present in the adult (since Freud). Humans are a type of animal, continuous with it rather than completely distinct (since Darwin). (My addition: Binaries are collapsing left, right and centre. This is always reflected in pop culture. A further example: the collapsing binary between the public and the private. Black Mirror is an excellent treatment of that. Any collapsing binary evokes a sense of moral uncanniness.)

- The child is becoming ‘the supreme object of love’, taking over from the romantic couple as ‘locus of the sacred’. This wasn’t the case 100 years ago, in a world with child labour, sexual abuse of children which wasn’t deemed abuse. We prioritise children in our (un)consciousness now.

- Since WW2 there has been an attempt to free the world of the idea that ‘might is right’. We’ve only had organisations which work things out between states since the end of WW2. Before then it was always brute force.

- These three phenomena combined mean we are fascinated by the small, plucky character. Caveat: The small, plucky character must be presented in a light-hearted register. Serious cuteness doesn’t work.

- Cuteness also breaks down the dichotomy between sincerity and insincerity. Sincerity, lionised since the eighteenth century (thanks to Rousseau), presupposes an inner world which is given expression in an external world. (Sincere is when actions are believed to line up with inner thoughts/emotions.) But cuteness has no inner world. If there’s no inner world there’s nothing to be either sincere or insincere about. Cuteness steps outside the cult of sincerity, hence the accusation of superficiality. But Simon May questions the degree to which we can really know ourselves. The very concept of sincerity presupposes a high level of interoceptive skills.

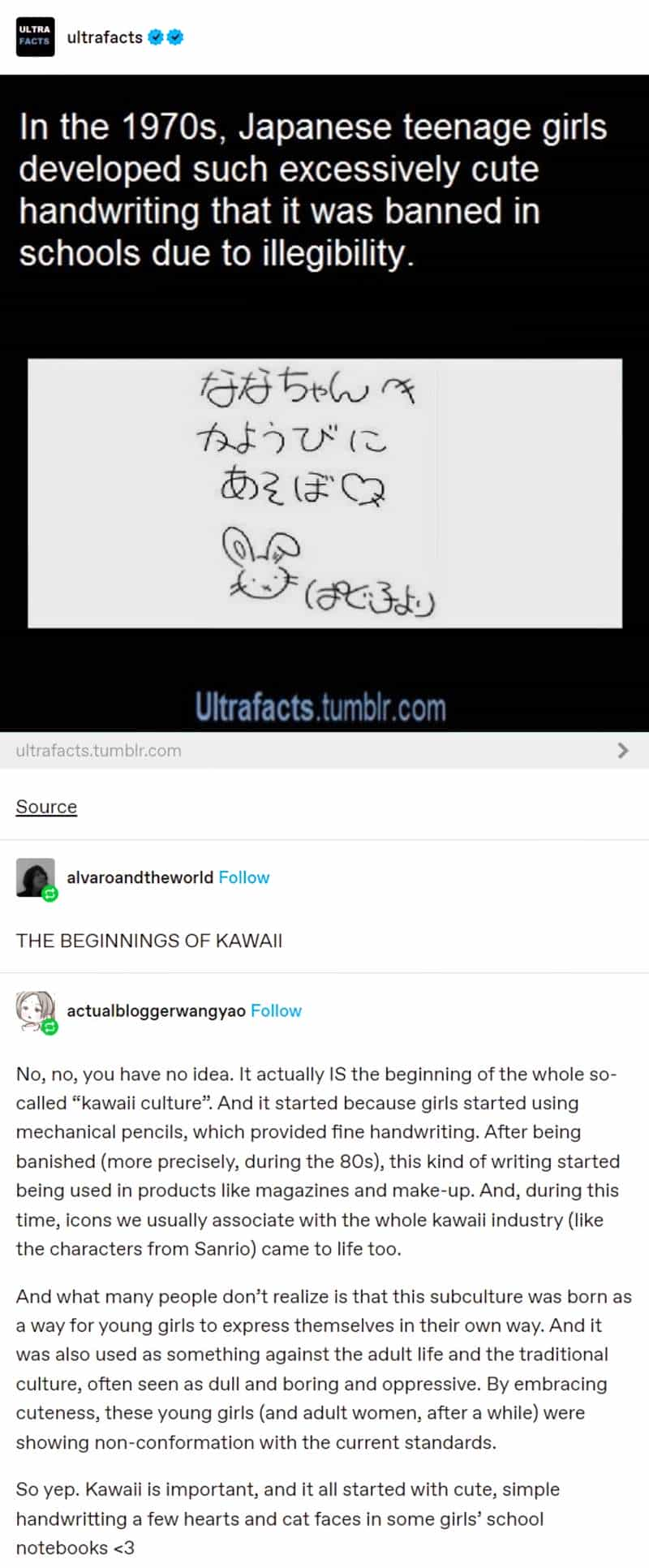

Why Did Cute (Kawaii) Take Off In Japan?

In comparison with the word utsukushii—meaning “beautiful” or “lovely”—the word kawaii is more playful. Things can be kimokawaii (creepy cute), busukawaii (ugly cute), or erokawaii (sexy cute). Kawaii is versatile and fun, while utsukushii has the burden of beauty.

The Meaning Of Kawaii by Brian Ashcraft

Adding to that: dasakawaii (tacky-cute) from dasai (uncool) and gurokawaii (gory-cute) from guroi (grotesque).

ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD TACKY

As a way to comment on a person’s style or taste, the word “tacky” has distinctly southern origins, with its roots tracing back to the so-called “tackies” who tacked horses on South Carolina farms prior to the Civil War. The Tacky South (LSU Press, 2022) presents eighteen fun, insightful essays that examine connections between tackiness and the American South, ranging from nineteenth-century local color fiction and the television series Murder, She Wrote to red velvet cake and the ubiquitous influence of Dolly Parton. Charting the gender, race, and class constructions at work in regional aesthetics, The Tacky South explores what shifting notions of “tackiness” reveal about US culture as a whole and the role that region plays in addressing national and global issues of culture and identity.

New Books Network

- Japan is one of the major exporters of cute. Tentpole examples: Hello Kitty, Pokémon, Sylvanian Families, Gudetama etc.

- Japan perfectly illustrates the three mega-trends Simon May described above. (The new fasciantion for indeterminacy, child as supreme object of love, avoiding the notion that might is right.) Before WW2, cute wasn’t a thing in Japan, either. But after WW2, Japan had reasons to present itself as harmless.

- The explosion of cute happened earlier in Japan than in the West (the 60s and 70s versus the 80s). By that stage, Japan had started to self-present as The Cute Nation. The country even designated three young women as ‘ambassadors of cute‘. Cuteness has since become a (small but readily identifiable) part of their image.

- Japan has always been less tied to extreme opposites than the West. Japan is much more fluid in its worldview. A cliché regarding Japan: Things can be true and false at the same time. Japan celebrates indeterminacy in a way the West has only recently started to do.

- Not all Japanese people are happy with their country’s way of presenting itself as cute, feeling Japan won’t be taken seriously and that cuteness undermines dignity. There are vocal Japanese critics against cute.

- Simon May queries the notion that cute objects have no power. Cuteness has its own power. Anything people are attracted to is always going to wield its own power. This reminds me of what feminists and the queer community have been saying about femme-coded versus butch-coded individuals (femmes derive power from being looked at whereas butch (and masculo-coded) individuals have a different kind of power. Some would call the latter kind of power real power. (See The Male Gaze.)

- Simon May pushes back against the idea that cuteness is infantilising. It’s about play. Cute objects may look trivial, but the phenomena behind cuteness is very much not trivial.

- Cuteness has the power to expand our empathy. Anthropomorphising can be a way of gaining empathy. (See also: Why are there so many animals in children’s picture books?) This may seem counterintuitive, since by imposing our human-ness onto animals, we are taking away from the animal-ness of the animals. But no, psychologists have concluded that anthropomorphising expands our circle of morality. (See: Cuteness and Disgust: The Humanizing and Dehumanizing Effects of Emotion.)

- Empathy is a prerequisite of morality. We must feel our way into another being before acting morally towards them. (This is why genocidal regimes start by turning humans into animals and objects — dehumanisation) in the cultural imagination.

It seems to me that drag and cuteness have much in common. Both are forms of playful expression. Both play with dichotomies. (Drag specifically breaks down gender dichotomies by emphasising the extremes to draw our attention to gender a performance.)

How Is Kawaii Different From Western Cute?

The etymology of Japanese ‘kawaii’ is much older than the etymology of English ‘cute’.

The word kawaii has a long history. It dates back to the Heian Period (794-1185), the Golden Age of Japan. It’s said to have originated from the archaic word kaohayushi (顔映し), which described a face flushed red from embarrassment or guilt.

Kawaii 101: Behind the Cultural Phenomenon, Rakuten Travel Experiences

As the phonology changed, the associations also changed:

- embarrassing

- pitiable

- vulnerable

- small

- cute

- lovable

Kawaii meaning ‘cute’ and ‘lovable’ happened in the Muromachi period (1336-1573). If you go to Japan, this is probably one of the first words you’ll hear, and the first you’ll learn. It’s used all the time, especially by girls and young women. Why young women? Sharon Kinsella has interesting observations on this: Because kawaii is associated with youthful femininity, by making frequent use of the word ‘kawaii’, women can appear to remain young and thereby escape the compulsory (hetero)sexuality of Japan which leads to marriage and children (with no government preschool care and so on).

The usage has widened. These days, kawaii is the generic, go-to thing to say about anything considered good or worthy of compliment.

In English, ‘cute’ also has many meanings which change depending on who/what the word describes. A ‘cute’ kitten is adorable. A ‘cute’ young man is desirable in a non-threatening way. A ‘cute’ dress is sexy and sassy. A ‘cute’ retort is a clapback which calls out someone’s performative, attention-seeking comment: “Oh, aren’t you cute.” We don’t tend to use ‘cute’ in such a widely generic manner. Instead we have ‘cool’; perhaps ‘nice’ or ‘awesome’.

Although Japanese concatenates ‘kawaii’ with other adjectives, clearly widening and playing with the word, even in English, cute is a spectrum, with sweet at one end, then uncanny/unsettling, then threatening. The monstrous is basically a hybrid between two familiar forms. Something can be charming and grotesque at once. The unnerving juxtaposition is the very thing that makes it compelling. Simon May sees ‘cute’ as a modern manifestation of an ancient and powerful archetype.

Example: Kim Jong Un, deliberately presented as gender ambiguous (as both mother and father) and also strangely vulnerable (he is famously afraid of flying). This isn’t a ‘sweet’ kind of cute, but is unsettling. Where do we stand with this guy? What might he do? Likewise, Trump is a hybrid between the known and the unknown. Simon May theorises that Trump’s cuteness is what allows him to get away with so much, including insincerity. (Remember, cuteness sidesteps sincerity altogether.)

Cute and Consumerism

In Troublesome Things: A History of fairies and fairy stories, author Diane Purkiss asks what happens to us when we see something cute and wish to covet it. Purkiss writes that female consumerism began in the late seventeenth century. What has this to do with fairies? This is when you see ‘court dwarves’ and ‘fairy baby freaks’ in art and literature. The connection?

There was so much more to shop for, so many exotic, delicious luxuries, trade goods, the spoils of a growing empire, spoils which included cute fairy freaks. Consumer, consumption — not, perhaps, such fun for the thing consumed. Maternal erotics can also be a love of conquest.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of fairies and fairy stories

If you grew up on literature from the Second Golden Age of Children’s Literature, you may remember the happy, cheerful, exuberant children, pitted against the scowlers and the sulkers, who either changed their demeanours quick-smart or were punished. In the work of Enid Blyton, for example, anything other than happy was considered sulking, a word which ascribes a communicative intent to an emotion: Look at me, I’m telling you I’m not happy, in a passive-aggressive way. (Not because I’m a child and I’m allowed to feel bad emotions without having the words, let alone the interoceptive skills to articulate what’s wrong.)

Baby boomer children were expected to be cute. Not sulkers, not scowlers. Good children were happy children. Baby boomers, as children, were held responsible for the wartime trauma of their parents. The children of their literature served as role models in ‘holding it all together’.

Diane Purkiss takes this happiness requirement back further than the 20th century wars:

The late Victorian child and the Edwardian child simply must be happy, simply must gratify their parents by being in paroxysms of soppy joy every time they venture into the nursery. In literature, child gaiety serves another purpose; it allows adult narcissism to flower. Adults can enjoy imagining that they too were once just as attractive as the fictional children prancing before them, while luxuriating self-pityingly in regret for the loss of the innocence fictionally grafted on to the young.

Cute fairies are adults’ attempts not to recover but to repair their childhoods, to make them over as simpler and nicer than any real childhood can be. We do not long for what we had, but for what we never had, which is why fairies always seem so hideously disjunct from real childhood, real children. […] The Cute World exists just for the adult, and the child must play along. […]

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of fairies and fairy stories

What, then, to make of those 1940s ‘cute’ characters who seem sad? Purkiss also writes that ‘The cute is often seen as forlorn, lacking something, somehow sad, needy… Fairy cuteness arouses a profound maternal desire to nurture, a maternal longing, a desire to rescue the cute object and put it within a family context.’ We find babies cute partly because they need us. (We like romantic partners, also, when we feel that on some level they need us… but not too much.)

Cuteness leads to coveting, which marketers have learned to utilise with great skill:

Shopping is about the longing to possess something cute … and to take it home, add it to the home.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of fairies and fairy stories

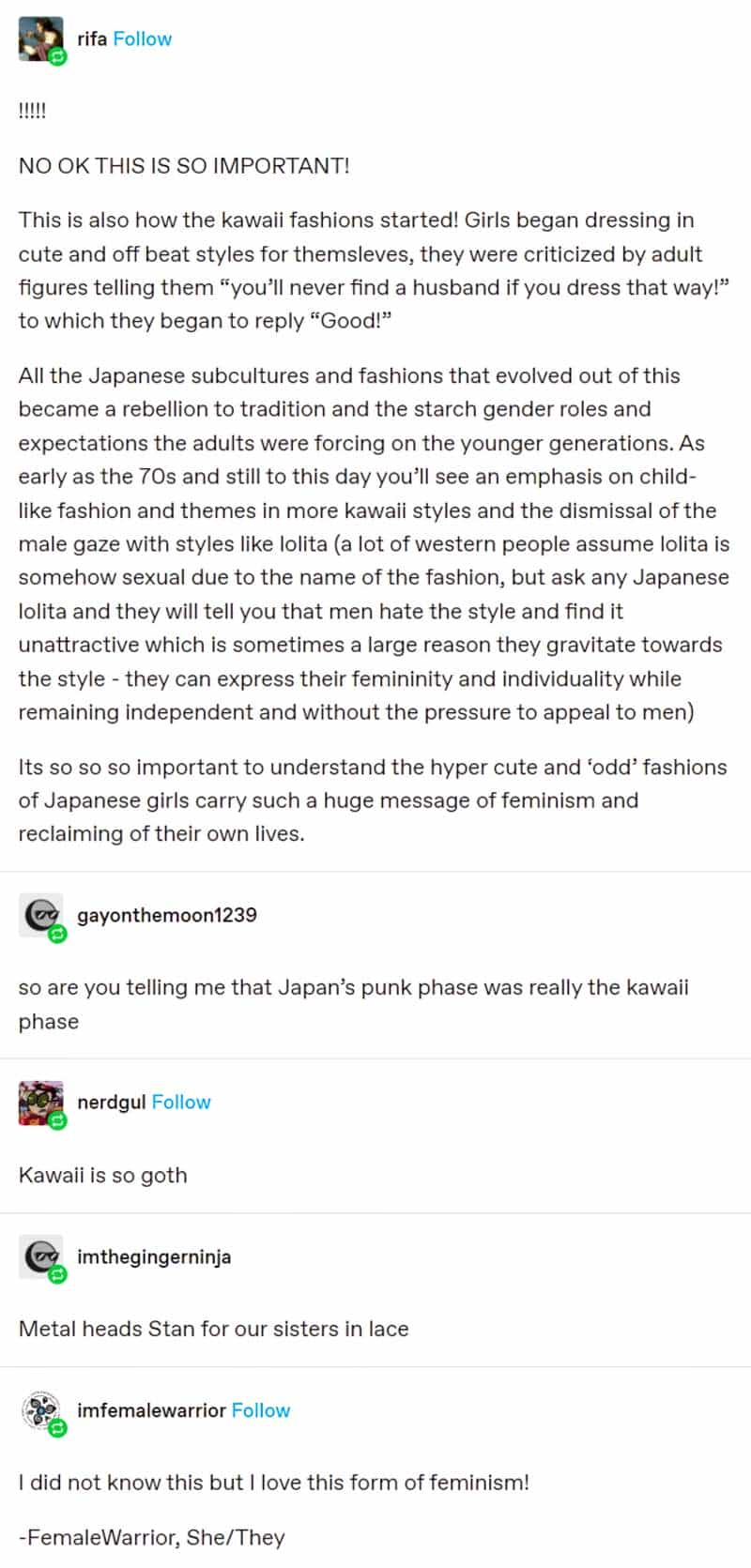

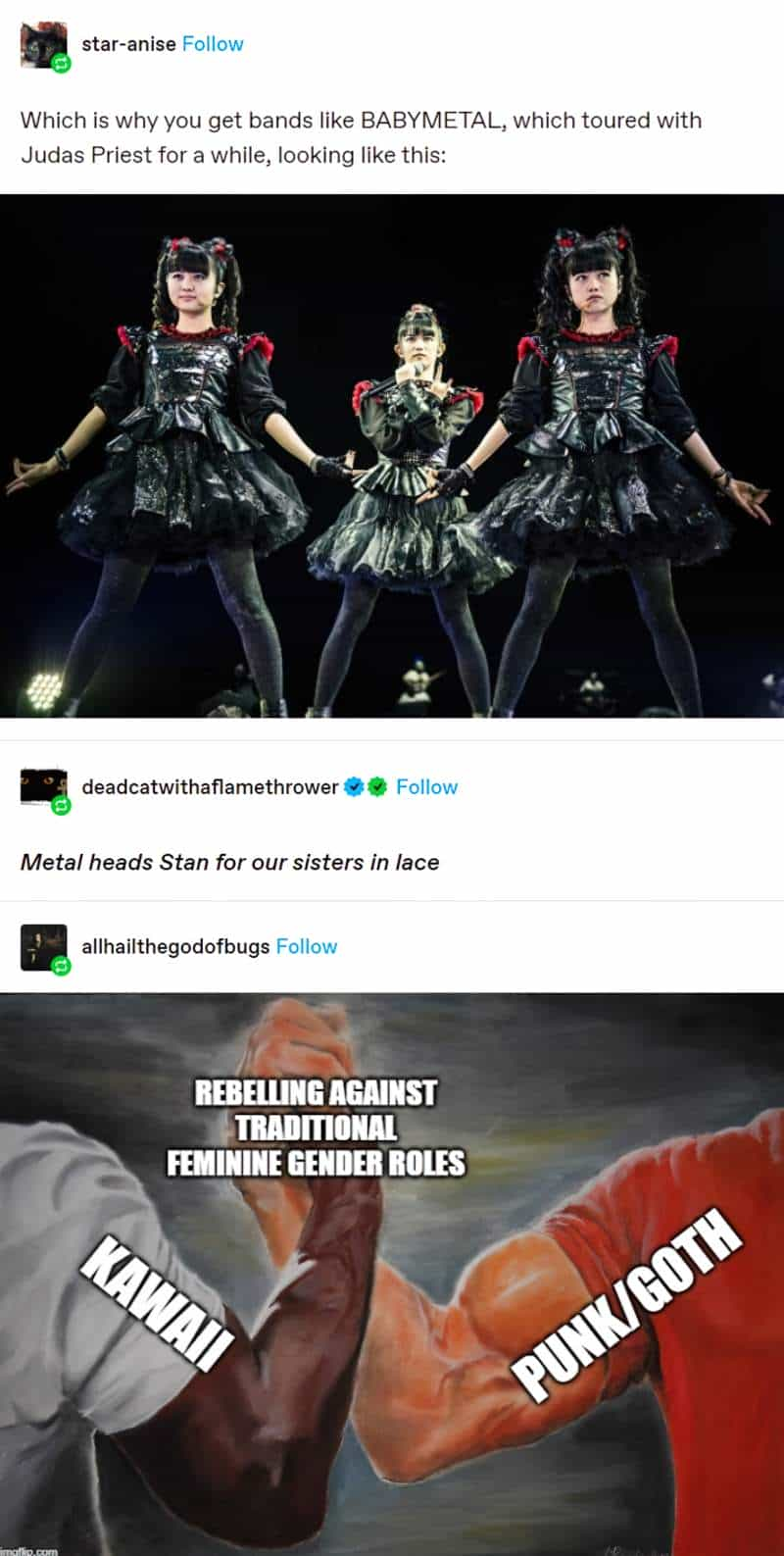

KAWAII AS JAPANESE PUNK/GOTH

FURTHER READING

‘Pure Invention’: How Japan’s pop culture became the ‘lingua franca’ of the internet from The Japan Times

The difference between kitsch and camp. Unlike kitsch, cute is not retro. Cute is ‘achingly contemporary’. Cute is part of kitsch, and is a worldwide phenomenon but cute is interesting because it tracks the rise of East Asia. The cultural flow moves from East to West.

The Moral Uncanny in Netflix’s Black Mirror by M Gibson and C Carden (2021)

“You have adorablitis.”

@MicroFlashFic

“Is it serious?”

“It’s terminal.”

“What’s going to happen?”

“You’ll get cuter each day.”

“Is that bad?”

“Not at first. But then you’ll start triggering people’s cute aggression response, until you’re so adorable no one can resist crushing your windpipe.”

OUR AESTHETIC CATEGORIES: ZANY, CUTE, INTERESTING BY SIANNE NGAI (2015)

The zany, the cute, and the interesting saturate postmodern culture. They dominate the look of its art and commodities as well as our discourse about the ambivalent feelings these objects often inspire. In this radiant study, Sianne Ngai offers a theory of the aesthetic categories that most people use to process the hypercommodified, mass-mediated, performance-driven world of late capitalism, treating them with the same seriousness philosophers have reserved for analysis of the beautiful and the sublime.

Ngai explores how each of these aesthetic categories expresses conflicting feelings that connect to the ways in which postmodern subjects work, exchange, and consume. As a style of performing that takes the form of affective labor, the zany is bound up with production and engages our playfulness and our sense of desperation. The interesting is tied to the circulation of discourse and inspires interest but also boredom. The cute’s involvement with consumption brings out feelings of tenderness and aggression simultaneously. At the deepest level, Ngai argues, these equivocal categories are about our complex relationship to performing, information, and commodities.

RACIST LOVE ASIAN ABSTRACTION AND THE PLEASURES OF FANTASY BY LESLIE BOW (2022)

Just finished this brilliant, if chilling, book about the fetishizing of identity/ Asian women. I couldn’t stop reading, but it was challenging to face the deeply pervasive levels at which one is figured as an object to serve white men especially, but white people in general. The entwined discourses of the machine and Asian women, the crucial element of fetishizing the “cute” so pervasive in Hello Kitty, anime, objectified Asians as kitchen tools, handbags, and perfume bottles, articulate the dominant’s attempt to control anxiety in the face of Asian capitalism/ geopolitical power, and of the enviable/ scary implications of “Model Minority” achievement. How threatening can they be if they are juicers? Animated cars? Sex dolls? Here, Elaine Chou’s brilliant but deeply disturbing article in THE CUT comes to mind. Both Bow and Chou leave us with deeply disturbing, intellectually compelling, affectively nauseating (in a profound way!) provocations. Both are urgent and necessary, giving coherent shape to the lifetime of objectification that Asian/ American women experience. Brava!

(The above was written by @DorinneKondo, Scholar of theater and performance studies, critical race studies, Asian American Studies. Cultural anthropologist.)

Interview with the author at the New Books Network

DESIGNING MODERN JAPAN

Sarah Teasley’s Designing Modern Japan (Reaktion, 2022) unpicks the history of Japanese design from the mid-nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth, focusing on continuities and disruptions within communities and practices of design. Designing Modern Japan explores design in the unfolding contexts of modernization, empire and war, defeat and reconstruction, postwar economic acceleration, and beyond. Throughout, Teasley is sensitive to issues of gender and class within the communities of design she studies. The book combines the history of design with social, economic, and geopolitical history, placing design and its material objects carefully in the larger currents of modern and contemporary Japan. Designing Modern Japan is a history of both the people who shaped Japanese design and the designs that were integral to life in modern Japan.

New Books Network