Are we supposed to be curious, or aren’t we? From reading stories, I just can’t make up my mind. If I open the box to find out what’s inside I risk unleashing evils across the entire world. But if I don’t open the box, there might be a bomb inside. If only I’d opened that confounded box, I could’ve saved everyone!

According to box office earnings in movies, curiosity in main characters is an excellent attribute to give them, along with gratitude and humility.

But today I’ll take a closer look at some popular historical narratives which seem to discourage curiosity as a valuable character trait, some which encourage it, and some which do both. Perhaps the reason audiences love curious characters today is because curiosity has so often been punished in the recent past.

Without the resources to do an actual count up, punishment for curiosity in fiction does seem gendered. It’s possible that if we took every single story in which a character is punished for their curiosity, more male characters than female characters are punished for it. But then, most stories are historically about men so we’d have to adjust for that first. It’s certainly the case that in the best-known myths and fairytales young (and beautiful) women are punished for poking their noses into affairs that don’t concern them, which would be fully in line with the ancient rules of patriarchy.

However, narrative doesn’t track along one linear progression from ‘super misogynistic’ to ‘super enlightened’. (We haven’t seen super enlightened yet.) All too often, those ancient tales, when retold for children, are repackaged with extra blame heaped upon curious young women.

Let’s see how that works.

Curiosity Killed The Girl

Below are The Big Three narratives which place the blame for all things bad on women, or upon a specific woman, standing in for all women. French has a term for this: cherchez la femme, which basically means ‘look for the woman’. It works the same as ‘follow the money’, meaning that if there’s a colossal stuff up, a woman is behind it. (Pronunciation here.) Do you know what started The Trojan War (among other things)? The Judgement of Paris. Athena and Hera were slighted when Paris said Aphrodite was the most beautiful goddess.

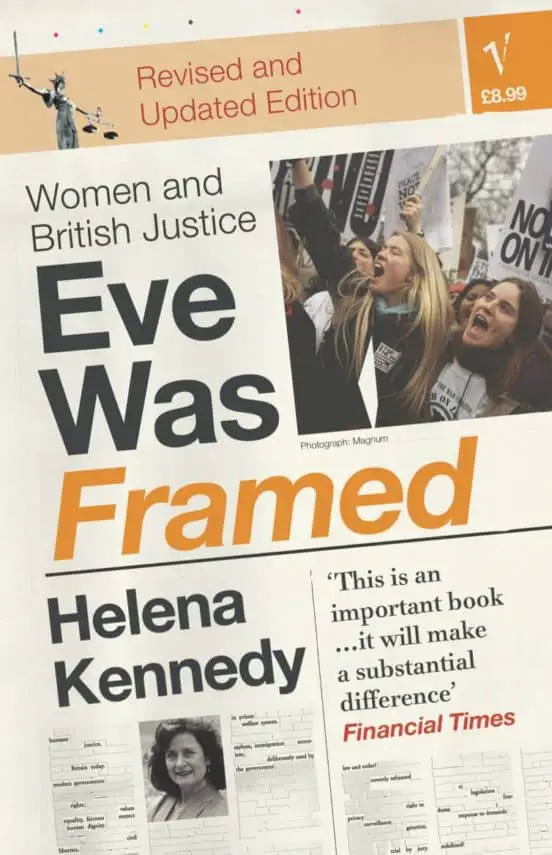

1. Eve in the Garden of Eden

In which Eve picks fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and ruins everything. This story is so famous I don’t need to go into it here, but I want to point out that the character of Eve has historically been conflated with the character of Pandora. (A bit more about that here.)

Eve Was Framed offers an impassioned, personal critique of the British legal system.

Helena Kennedy focuses on the treatment of women in our courts – at the prejudices of judges, the misconceptions of jurors, the labyrinths of court procedures and the influence of the media. But the inequities she uncovers could apply equally to any disadvantaged group – to those whose cases are subtly affected by race, class poverty or politics, or who are burdened, even before they appear in court, by misleading stereotypes.

2. Pandora’s Box

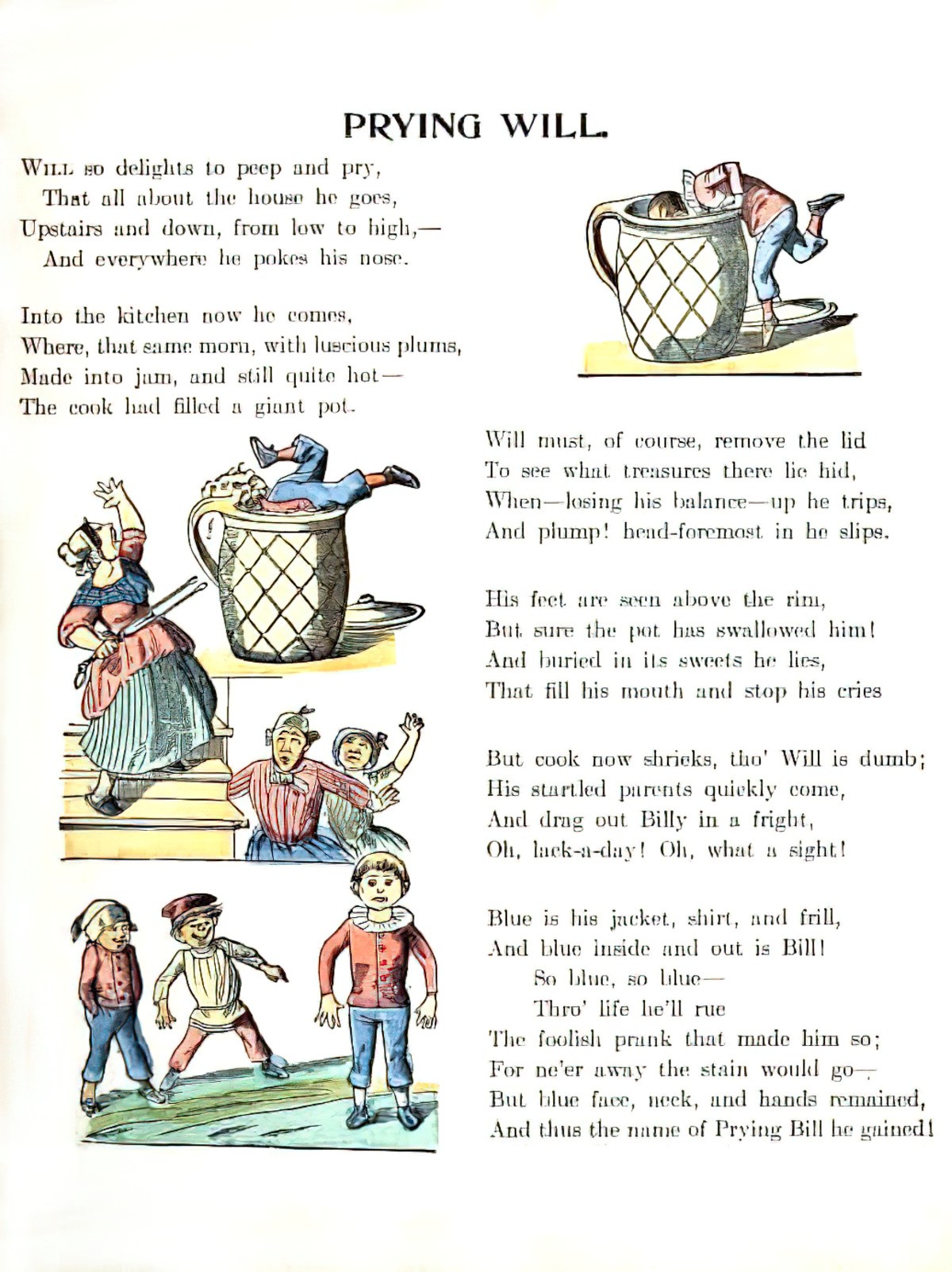

Like all the popular Greek myths, Pandora’s Box has been bowdlerised for children over the years, and there are two popular examples which have influenced how we think of Pandora today.

The first can be found in the Tanglewood Tales For Boys and Girls by Nathaniel Hawthorne. This was published in 1853, so is out of copyright. It’s freely available at Project Gutenberg, and you just need to scroll down to the chapter called “Pandora”, though Pandora’s story actually begins at the end of the previous chapter, in which Pandora is introduced as a highly dislikeable ‘pettish’ little girl. I had to look up the meaning of pettish: childishly bad-tempered and petulent.

I don’t actually recommend reading Hawthorne’s “Pandora”; it’ll likely give you the irrits, either because you find Pandora annoying, or because the misogyny of the author shines through in his generous, empathetic portrayal of Epimetheus, which highlights the coding of Pandora as a whiny, nagging brat. Her disagreeable nature comes through in her perseverating over that confounded box and also in her dialogue tags. Hawthorne’s depiction of Pandora is an exaggerated version of Harry Potter’s Hermione, with no redemption arc.

Points of interest in Hawthorne’s “Pandora”:

- The box has been delivered by a man called Quicksilver, another name for mercury, also the Roman name for Hermes. Children won’t pick up this pun unless they are already familiar with the Greek myths. This joke’s for the adult co-reader.

Actually, that’s it. That’s the single point of interest in the Hawthorne “Pandora” chapter. Basically, Hawthorne’s Pandora won’t drop the subject of the box, but Epimetheus is incurious, as he is meant to be. I see links here to the concept of ‘gossip’, which is usually connected to women, and is considered the immoral outworking of interest in other people (but which is actually necessary to the functioning of any given society, and a natural flipside to looking after other people, as women are required to do). Cf. The gossipy Rachel Lyndes of children’s literature.

Notice, too, how Hawthorne makes use of the passive voice to erase all the gods in Olympus who made her, placing culpability squarely on the shoulders of Pandora.

The second influential Pandora for children can be found in a collection about 100 years more recent: Tales of the Greek Heroes by Roger Lancelyn Green (1958).

In Green’s “Pandora” retelling, Pandora again gets all the blame:

- She is told the casket is full of treasure while Epimetheus is out (absolving him completely).

- She creeps around quietly (suggesting evil intent and a guilty conscience).

When bowdlerising the Pandora myth for children, both Hawthorne and Green slap a whole lot of blame on Pandora which wasn’t there in various earlier renditions, and that’s saying something, because the Ancient Greeks weren’t known for their gender equality.

As Natalie Haynes writes in her book Pandora’s Jar, the earliest written versions of the Ancient Greek Pandora myth turn Pandora into part of the trickery — an object, basically, who is used to trick the hapless Epithemeus as the box (actually the jar) is used to trick him. That’s not to say these versions were free of misogyny — quite the reverse.

When we talk about very early versions of the Pandora myth, we’re talking about those written down by Hesiod.

Hesiod (8th C BCE) was a Greek poet. Hesiod told two Pandora stories:

1. “Theogony”, an origin story poem (First comes Chaos, then Earth etc.) After a whole lot of melodrama Hesiod describes a deadly race of women. Pandora isn’t mentioned by name and also Hesiod considers women an entirely different race. I’m reminded of kids who think cats and dogs are female and male versions of the same species; this is kind of the inverse. Hesiod cracked on that men and women come from entirely different species, and Pandora is the ancestor/antecedent of all women. The unnamed Pandora doesn’t have any kind of jar or box at this stage.

We learn that Pandora is made of the earth (the word for this is ‘autochthonous’). She was created by Hephaestus, the gods’ master craftsman. She was decorated by Athene (cunning and skilled). Pandora is beautiful but also evil. It seems Hesiod the writer is turned on by his own creation.

Like a modern day MRA, Hesiod talks about how women are only interested in men if men are not poor. He also compares women to bees (but not in a good way).

2. A more fleshed out Pandora can be found in Hesiod’s later Works and Days. Pandora is created as a temptress in this heteronormative story ‘in which all men will delight, and which they will all embrace’. Although Pandora is made out of earth and water, she has the face of an immortal goddess. She’s given a whole lot of gifts: Athene teaches her how to weave. Aphrodite gives her golden grace, painful desire and limb-gnawing sufferings. I think this is probably a transferred epithet — surely this is how men felt when they gazed upon her rather than a description of Pandora’s own sufferings? We dont’ know how Pandora felt. But not all her gifts are good ones: Hermes gives her a dog-like mind (the Ancient Greeks didn’t like dogs) and a dishonest nature. Hermes is also the god who gives Pandora her name. Hermes delivers Pandora to Epimetheus (outside the immortal realm). Epimetheus is the brother of Prometheus. Prometheus means foresight and ‘Epimetheus’ means hindsight. Prometheus has previously warned his brother not to accept any gifts from the gods, but because Epimetheus has a shortcoming that matches his symbolic name, he’s forgotten that advice, and now he has a beautiful woman. Until this moment, the life of mortals was happy and carefree with no disease, no hard work, but now, because of this evil woman, everyone is miserable. All because Pandora takes the lid off the jar.

One thing stays inside the jar: Hope. (Elpis) Hope kind of gets stuck under the lip of the jar. (Hope is better translated as ‘expectation’.)

Remember this point: Pandora is herself a gift (an evil one) and before she was gifted to a mortal man the gods all gave her a gift: a voice, a dress, the ability to weave etc.

Does this remind you of Sleeping Beauty? In the fairytale, the gods are now fairies, and the one wicked fairy who was never invited is Pandora herself, in this weird mish-mash of gifting and the gifted. (We need an updated Pandora story called Gifted.)

As Natalie Haynes points out in her criticism of the Hawthorne and Green’s Pandora bowdlerisations, there are much kinder Pandora takes which could’ve served as Ur-texts, but weren’t.

The first example of a more sympathetic Pandora can be seen in a short passage from Elegies (by Theognis, 6th century BCE) suggesting the jar is full of good things, not evil. (Self-control, trust etc. fly away and that’s why they’re hard to come by among men. The fact that they fly away is hardly Pandora’s fault.)

Then there’s Aesop. I hadn’t realised there’s also a Pandora story to be found among the Aesop fables. In the Aesop version, the jar is also full of good things (as it is in the Theognis fragment) and it’s not even Pandora who takes the lid off the container. A ‘curious or greedy’ man takes the lid off. He remains unnamed. And I extrapoloate that because he’s a man, he’s not automatically coded as evil, but simply as curious or greedy — normal human foibles rather than supernaturally destructive ones.

A SLIGHT DIGRESSION ABOUT MISOGYNY INSERTED INTO AESOP FABLES

Morals are separate from their stories. Aesop’s Pandora is nowhere near as grating or guilty as Hawthorne’s, or Green’s.

I have previously noticed that Aesop’s fables are regularly updated for children with extra misogyny baked in. A few years ago I picked up a beautiful second hand edition of “The Ant and the Grasshopper“, a 2005 publication by Randall and Gardner, and realised something disturbing about how a story such as this can be gender flipped badly by contemporary authors, perhaps under the pretext of gender diversity (inclusion). Earlier fables like this gender the animals as male by default, but as soon as female characters come into the story, there’s opportunity to mess the whole thing up.

First, take a look at a much earlier written version of “The Ant and the Grasshopper”. This is from Anianus (L’Estrange, 1692):

As the ants were airing their provisions one winter, up comes a hungry grasshopper to ’em, and begs a charity. They told him that he should have wrought in summer, if he would not have wanted in winter.

“Well,” says the grasshopper, “but I was not idle neither; for I sung out the whole season.”

“Nay then,” said they, “you shall e’en do well to make a merry year on’t, and dance in winter to the tune that you sung in summer.”

Notice the gendering? No, I don’t either. Leaving aside the slight complication that people who really know their insects know the very nature of gendering is somewhat problematic — I mean, bees can really blow your mind, not that bees exist in the original — the 1692 version does not gender its insect characters (except for the grasshopper, that is).

Flash forward to 2001 when Bright Sparks decides to reissue and expand upon these out-of-copyright fables. Now we need to assign genders to the characters, and because there’s this phenomenon which we might call The Female Maturity Formula, storytellers gender the fun-loving but immature grasshopper male, and surround him with female characters who exist to teach him the lesson of planning ahead and hard work.

Not only that.

Much earlier versions of this tale — and similar classic tales such as “The Little Red Hen” — leave the lazy characters to reap their just rewards. Aesop did not save the grasshopper. Oh no, the grasshopper died.

But in this 2005 adaptation of Aesop’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper”, the industrious ant character — who has been working her butt off all summer as well as looking after four children of her own — is overwhelmed by the (crocodile) tears coming out of the hungry grasshopper and takes him in.

“Well, you were wrong, weren’t you,” said Ant. “If you play all Summer, then you must go hungry all Winter.”

“Yes,” said Grasshopper, sadly, as a tiny tear fell from the corner of his eye. “I have learned my lesson now. I just hope it isn’t too late!”

Ant’s heart softened. “Okay, come on in,” she said. “And I’ll find some food for you.”

All too often, female characters exist in children’s stories not only to teach boys lessons but also to be self-sacrificing.

Aesop’s moral: If you don’t plan ahead you can die.

Well, that’s one of the dominant morals. Jerry Griswold explains several dominant interpretations of this tale:

In the well known story of “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” the ant is busy all summer collecting food and the grasshopper fiddles his time away. Then winter comes and the grasshopper begs for food from the industrious ant but is turned away hungry with a lecture about being prudent. The moral we are often told — let’s call it the “conservative” one — concerns the need to work hard and plan for the future. But another moral — let’s call it the “liberal” one — could just as easily be that all work and no play makes one as selfish as the ant.

Jerry Griswold

This liberal interpretation becomes completely lost in the 2005 bowdlerisation.

2005 moral: Boys, you can muck around as much as you like. As long as you show remorse all will be well. Also: Girls, you exist to take care of your own children as well as to teach random boys lessons. And if you say no to sharing you are a hard-hearted beatch.

Back to Pandora, here’s why Curious Pandora should never have been given the blame for opening the jar/box whatever it was:

- Zeus sent Pandora down to earth with the jar, so why not blame Zeus for giving it to her? Or why not blame Epimetheus for failing to heed his brother’s advice not to accept any gifts from the gods?

- We forgive Zeus; he is the most powerful of the Olympian gods and he can do what he likes.

- We forgive Epimetheus; he has been tricked by Zeus, the most powerful of gods.

- We don’t even remember Hermes, who is supposed to have given her a dog-like mind and a deceitful nature. (Did he not think that was going to come back to bite people?)

- We blame Pandora, who is used as a tool of trickery, literally gifted as an object, used as an object.

- We have no evidence that Pandora knew what was inside the jar before she opened it.

- Classics scholars don’t agree about whether keeping hope in the jar is a good thing or not. Is Pandora depriving humanity of hope? Or is she keeping it safe so we will always have it?

- Making matters more ambiguous, ‘elpsis’ doesn’t map onto modern English ‘hope’ exactly. We might also translate it as ‘expectation’, because the thing we anticipate with ‘elpsis’ is neither good nor bad.

3. Bluebeard

Is “Bluebeard” a permutation of the “Pandora” myth? I think so. Both involve a young attractive woman who goes somewhere she shouldn’t. Actually, Pandora was never told not to open the box, whereas the heroine of Bluebeard was expressly forbidden to use the key, which her husband put within her reach, then told her about. (The key is basically Eve’s apple, no?)

I never encountered the Bluebeard tale in my childhood exposure to fairytales, suggesting it’s often left out of bowderlised fairytale collections for children, or skipped over. I encountered Bluebeard plots before I came across the Bluebeard fairytale. I wonder if my experience is typical. Let’s just say, it’s not exactly G-rated, no matter how you bowdlerise it.

In “Bluebeard”, an abusive, murderous husband gets older and older while continuing to marry young women, killing them in succession as they each discover the dead bodies of former wives in his basement. Although this story was probably designed by women for women, as an outworking of typically feminine fears around marriage, bowdlerised versions of this fairytale have tended to convey a more simple message: If only the young wife had done as she was told, she would’ve been safe.

Angela Carter subverted the “Bluebeard” story entirely when she wrote “The Bloody Chamber“. For a mental mouthwash, I recommend it.

Blondine

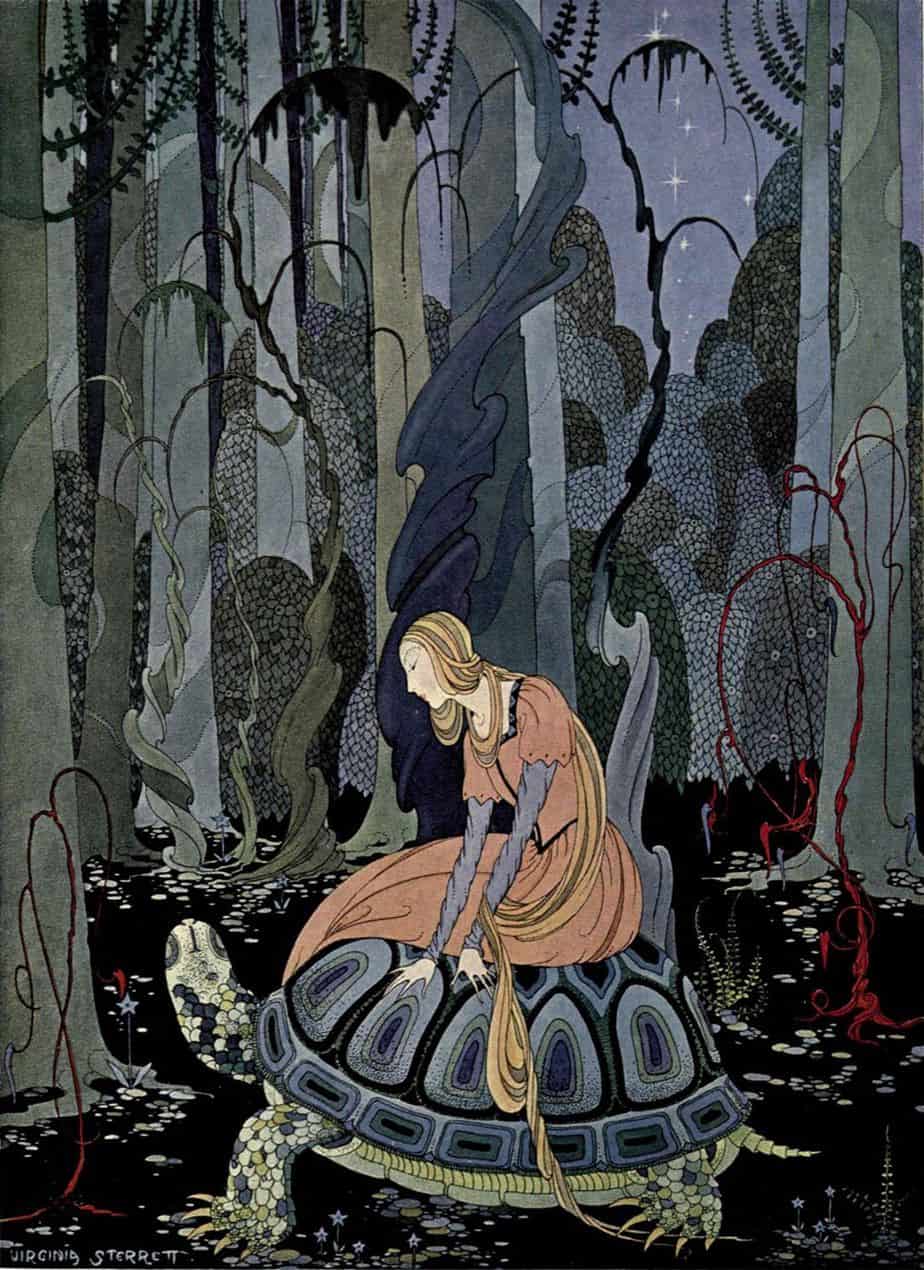

Then there are lesser-told myths which have nonetheless had a massive impact on cultures, both reflecting and changing them by their existence. In the old French fairytale below, a young woman is not allowed to ask a single damn question, to put her trust entirely in someone else.

“Blondine, I am not permitted to disclose to you the fate of your friends but if you have the courage to mount on my back, remain there for six months and not address a single question to me during the journey, I will conduct you to a place where all will be revealed.”

Blondine and the Tortoise, an old French fairytale

Curiosity and Crime Stories

The less you know, the happier you can be. This certainly applies to some extent in real life. These days I’d argue it’s necessary to prize yourself away from the maddening news cycle if you want some mental rest. The main characters of crime stories are often deeply unhappy people, whether they are the detectives or the crime lords.

The main characters of crime stories are all intensely curious. Curiosity is a wonderful trait for fiction — it drives action. Hence the popularity of crime stories.

Ray Donovan is a more recent take on the Tony Soprano archetype. Ray Donovan says to his brother Terry at one point, “Don’t ask if you don’t wanna know the answer.”

The clip below exposes Ray Donovan’s modus operandi: “You don’t wanna know what really happened.” For Ray, especially as the seasons progress, knowledge is unhappiness.

Curiosity In Contemporary Stories For Children

So what of modern children’s stories? Are modern children supposed to be curious, or not? From what I can make out, storytellers use curiosity as a curse or a virtue, to fit any given story.

Curiosity will conquer fear even more than bravery will.

James Stephens

ON CURIOSITY AND MORALITY

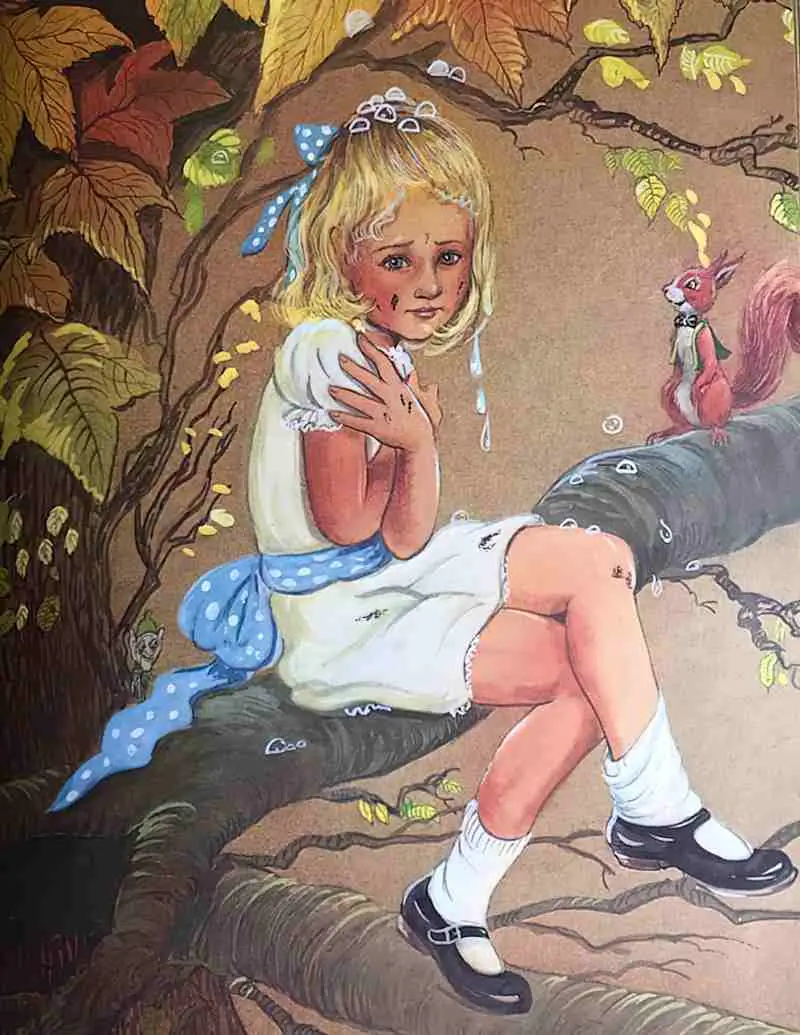

Enid Blyton’s The Folk of the Faraway Tree (1946) was the third book in Blyton’s popular and enduring Faraway Tree series. I know plenty of kids are still reading this series today, encouraged by parents and grandparents who also loved it. The character of Connie strikes me as an evolution of Hawthorne’s Pandora: A pretty girl arrives as a visitor and playmate for the designated nice children. Like Hawthorne’s Pandora, Connie is spoilt and ‘pettish’ (though Blyton never used that particular word), and her incuriosity is first punished when she first refuses to believe in the magic of the tree, and then her curiosity is also punished, when she changes her mind, based on evidence, and peers into one of the windows in the tree trunk.

So is Connie supposed to be curious, or isn’t she? Though I dutifully despised Connie as a child reader, the adult me admires the girl’s skepticism. If I’d believed every tall tale my cousins told me I’d have been in gullible trouble. I admire that Connie changes her mind when faced with actual evidence. Pretty sure that if I saw a window in a tree, I’d think I was losing my mind, but I’d also want to see if there was anything inside.

Perhaps you remember how often Blyton uses the word ‘queer’, meaning ‘curious’, or ‘intensely interesting’. Blyton’s characters were always curious types. But Blyton is a typical example of how a children’s author both rewards and punishes the trait of curiosity. Reward and punishment in a Blyton adventure is never contingent upon the act of curious investigation itself; rather, entirely contingent upon who was doing the investigation. The curious investigation of the designated empathetic characters equals good. The curious investigation of the designated immoral characters equals bad.

Connie is a spoilt brat who is given everything, including beautiful clothes. Likewise, Pandora has often been mistaken for a woman who was given everything and did nothing with her privilege but wreak havoc upon the world. The name “Connie” comes from a name that means “constant” or “steadfast” and I believe this (accidentally) describes the character of Connie perfectly. What about Pandora’s name?

Pan = all

Dora comes from didomi, “I give”.

It’s easy to make the mistake of thinking Pandora means a person who has been given everything, but her giving goes the other way, because the verb is active. Pandora refers to someone who is all giving rather than to someone who has been given everything. (In Greek, pandora often describes the earth, an all-giving thing which sustains life.)

We should regard Pandora as generous rather than a spoilt brat, but her reputation as a spoilt brat endures, hence all the beautiful, spoilt-brat Connie archetypes of children’s literature who are so often punished for ‘sticking their noses into other people’s business’.

Let’s fast forward a few decades from Blyton’s Connie. Harriet The Spy is rewarded for her curiosity, alongside many related child detectives. That said, child detectives usually come close to a metaphorical death while solving the neighbourhood crime, in a self-sacrificial kind of way. The cosiness of children’s crime stories fit along a continuum, but there’s always that danger of bodily harm lurking in the shadows. Crime stories for children align with crime stories for adults in their basic plot structure. The crime solver must be intensely curious or nothing will get solved.

Illustration by P.B Hickling from ‘The Inquistive Harvest Mouse’ by Noel Barr. Ladybird, this edition 1953

CURIOSITY IN PICTURE BOOKS

What about curiosity in picture books? Shaun Tan’s picture books aren’t really for the preschool set so aren’t exactly typical of the category, but in “The Lost Thing“, Tan tells a story in which a boy grows up and loses the magical childhood ability to notice details. This means his world gets more grey and less interesting. In another of Tan’s stories, “Rules Of Summer“, the message is similar, though even the child characters are incapable of noticing the world around them at times. Even in a story that’s not really about curiosity, “Eric“, the details in Tan’s illustrations send a similarly clear message: We must notice the small things. If we fail to take notice, we are really missing out (in this case, specifically self-knowledge).

In picture books for younger children, main characters typically notice the things adults do not, are open to unlikely fantasy happenings in their day-to-day world in a way that adults are not, and are rewarded for this interest with carnivalesque adventures a la Curious George.

USEFULLY INCURIOUS ADULTS IN CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

Adults, by negative example, are often the inattentive, incurious characters of a children’s book. To take a mid- 20th century example, Mrs Arable of Charlotte’s Web is a standout example of an inattentive, incurious adult. Fern’s mother is usefully vague (useful to the plot). When a storyteller creates an adult character who is vauge, they are effectively getting them out of the way so the child can have their own adventures. (In fairytale the mother might’ve been simply killed off.)

“Well!” said Mrs Arable. “Isn’t that nice!”

E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web, after Fern tells her mother she had ‘the best time’ at the fair.