“A Cup of Tea” is a Modernist short story by Katherine Mansfield, first published in May 1922. I’m reading it 100 years later.

Commentators commonly describe “A Cup Of Tea” as a story about jealously between women: A rich woman is jealous of a beautiful younger woman with no means — a modern re-visioning of Snow White. Is this really a story about jealousy, though? Below, I argue this is simplistic. Worse, it plays into a cultural stereotype about women in general — that women secretly hate each other, even while trying to be kind, and that a beautiful woman and a plain woman can never get along. Rosemary Fell is a Fairy Queen archetype. Mansfield uses her to say something about beauty standards as she experienced them in the early 20th century.

HOW RICH IS ROSEMARY FELL?

Reading this story, it’s clear the gap between rich and poor has gotten ridiculously wide in the last hundred years. Rosemary is introduced by an unseen narrator — as if gossiping to us, the reader — about a woman who is so wealthy she can just walk into a store and buy whatever she wants. But one day, she walks into a store, sees a cute little ornamental box and considers the price extravagant. Let’s take a closer look at the price, insofar as Internet tools help us, anyway.

How much was the little box? Twenty-eight guineas. What’s a guinea?

Guineas were a coin used in Britain between 1663 and 1814. This story was published long after that, in 1922, when Britons (and also Australians) were still using the term in certain specialised areas. But ‘guinea’ didn’t map perfectly onto a pound. One guinea was one pound and one shilling, or £1.05 in today’s currency.

The guinea had an aristocratic overtone, so professional fees, and prices of land, horses, art, bespoke tailoring, furniture, white goods and other “luxury” items were often quoted in guineas until a couple of years after decimalisation in 1971.

Wikipedia

Making use of a CPI website in 2022, £1 pound in 1922 equals £63.16 pounds. The ornamental box is worth about $1770 in today’s American dollars. If you’ve ever seen the Real Housewives reality TV shows, that no longer seems shocking, even for a tiny ornamental box with no real purpose. Real Housewives have budgets unfathomably large to the vast majority of us.

Are these women the modern-day Rosemary Fell?

The fantasy of having so much money you can buy anything you want must be wildly popular because a number of different franchises of Reality TV feature outlandish consumerism. Do we love to fantasise, or do we love to judge?

Rosemary Fell thinks it wasteful to spend a grand on an ornament. Yet the Yummy Mummies of Melbourne spend a lot more than that on their ‘push presents’.

The first series saw Lorinska, Jane and Rachel all receive extravagant ‘push presents’ after giving birth to their children, in the form of a $99,000 rare diamond ring, a Range Rover and a Rolex respectively.

Yummy Mummies: the reality TV show we really don’t need? Women’s Agenda

Below Deck Mediterranean is the Reality TV equivalent of Upstairs, Downstairs or Downton Abbey. When the Queen of Versailles charters a yacht, cameras follow as she spends a cool thirty thousand euros in a jewellery store. New Zealand crew member Aesha is required to help with the shopping, but can’t believe the extravagance. “When I was growing up, we couldn’t afford to buy cheese!”

Stories which juxtapose the poor against the wealthy are a surefire source of conflict. Economic conflict is especially interesting because income inequality affects us all, and it is only when the wealthy are forced to confront their own privilege that we see their morality. Rosemary Fell faces a moral dilemma: Does she continue to enjoy her own wealth to scratch a brief shopping itch, or does she reapportion pocket money to make another woman’s life significantly better?

SETTING OF “A CUP OF TEA”

PERIOD

Early 20th century

DURATION

An hour or so?

LOCATION

London

ARENA

Between the upmarket shopping precinct and Rosemary’s home

MANMADE SPACES

The shops, the house.

NATURAL SETTINGS

Characters don’t enter the wilderness. The wilderness is not typically associated with the wealthy. (Even when they enter the woods, the day is highly structured.) However, if we’re going with my Fairy Queen reading, the shopping district equals the fairytale woods. The house is a castle and also a prison.

WEATHER

When Rosemary exits the shop without buying the box, it is raining. We might interpret this as plain old pathetic fallacy. (Rosemary is sad about the box; the rain matches her internalised tears.)

The CodeX Cantina podcast point out that commonly when getting wet in the rain or walking through a river, this signals rebirth. Mansfield is setting us up to expect a character arc, in which Rosemary revisits her wicked ways after understanding the man in the shop is clearly taking her for a ride. We expect Rosemary will think more carefully about how her money would be better spent.

However, this is Mansfield we’re talking about. That’s not where she goes with this at all.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

Katherine Mansfield loved a good ‘container motif‘, a type of symbolism typically associated with femme coded characters. Mansfield’s standout short story “Prelude” features various tiny containers, from the matchbox to the pillbox. In “Prelude”, this motif contributes to the larger theme of restriction and social containment.

In “A Cup of Tea” we have another box, which other readers have read as a music box. (The musical aspect of it isn’t on the page.) Here’s the description of it:

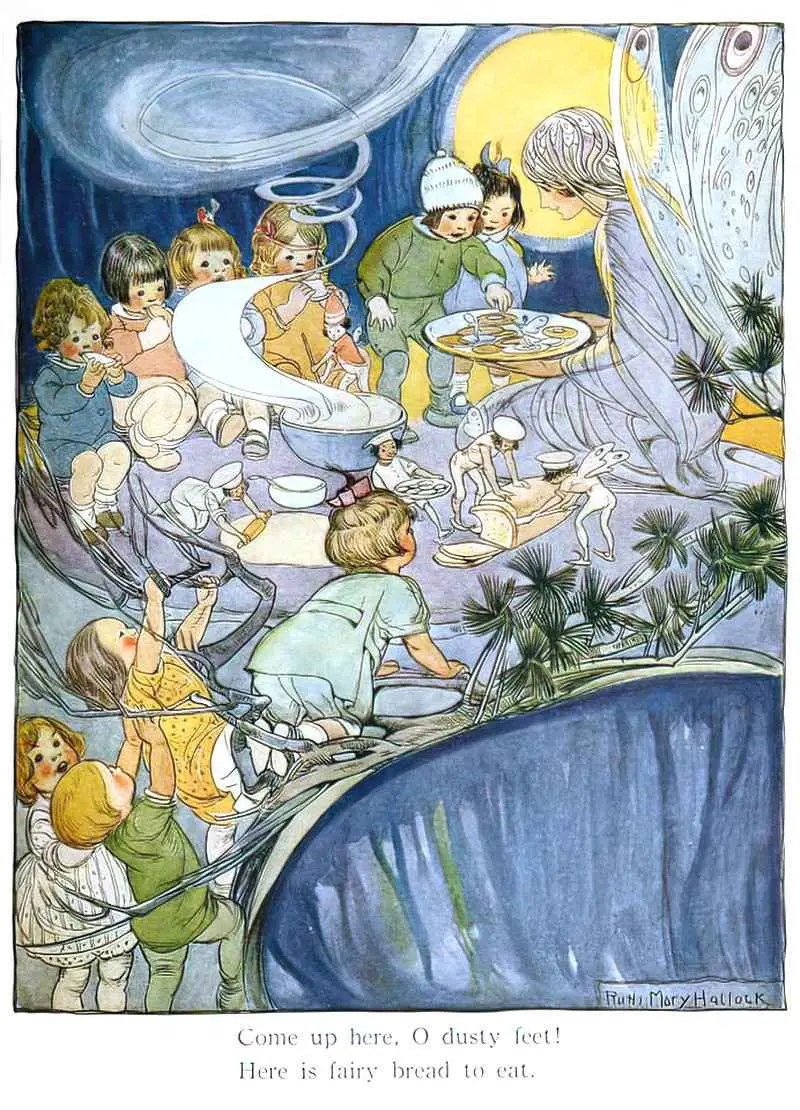

An exquisite little enamel box with a glaze so fine it looked as though it had been baked in cream. On the lid a minute creature stood under a flowery tree, and a more minute creature still had her arms round his neck. Her hat, really no bigger than a geranium petal, hung from a branch; it had green ribbons. And there was a pink cloud like a watchful cherub floating above their heads.

“A Cup of Tea” by Katherine Mansfield

Rosemary falls in love with the box, which tells us a lot about her. What is it she loves? The imagery is Romantic and speaks to a Rosemary’s desire to be loved in a grand-gesture kind of way. Note that she recreates the pose with her husband later, emulating the coquettish pose of the female fairy.

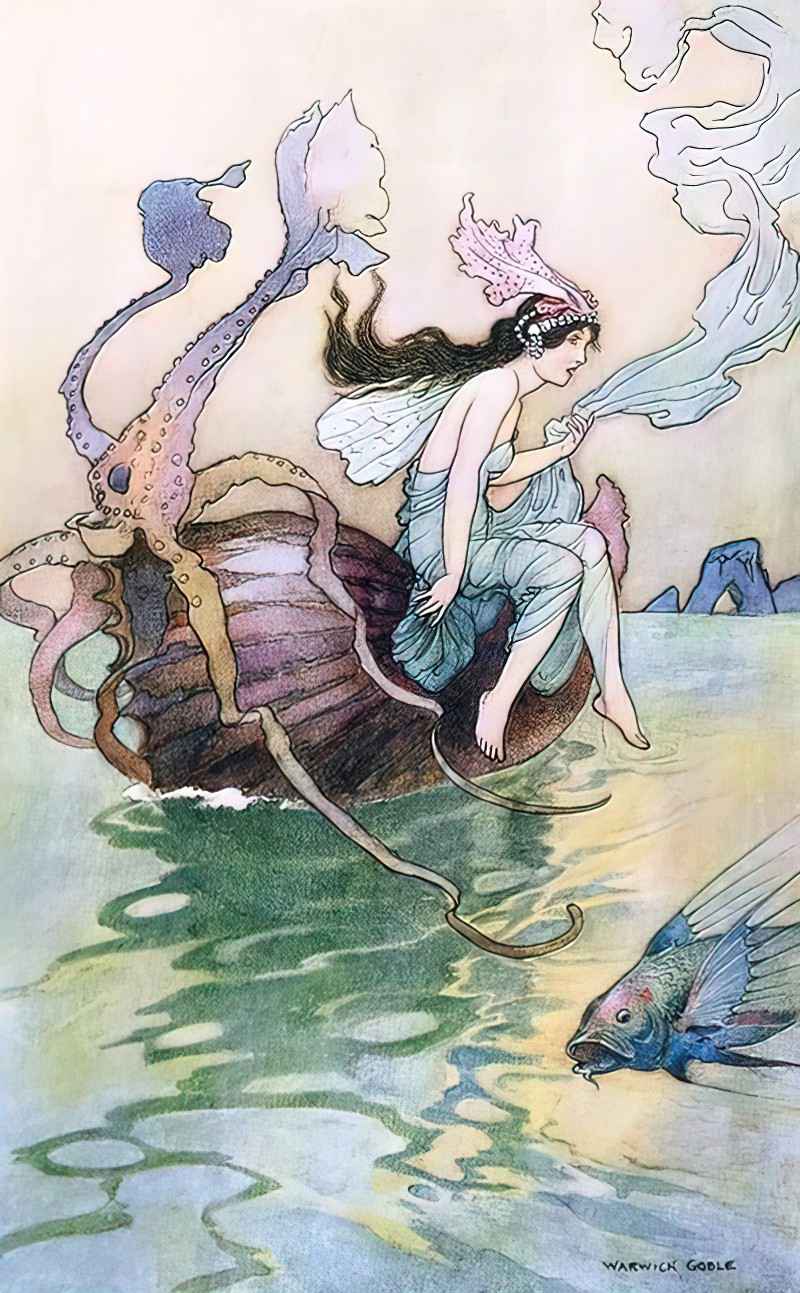

At least, I believe she’s looking at an image of a fairy. Fairies and flowers in art were popular in the early 20th century. So were creepy cherubs. This was the heyday of illustration such as Ethel Jackson Morris, Cicely Mary Barker and Percy Tarrant. Mansfield would have grown up with John Anster Fitzgerald and Richard Doyle. Harold Gaze was a New Zealand-born illustrator of fairies who continued the tradition a little past Mansfield’s time, alongside others.

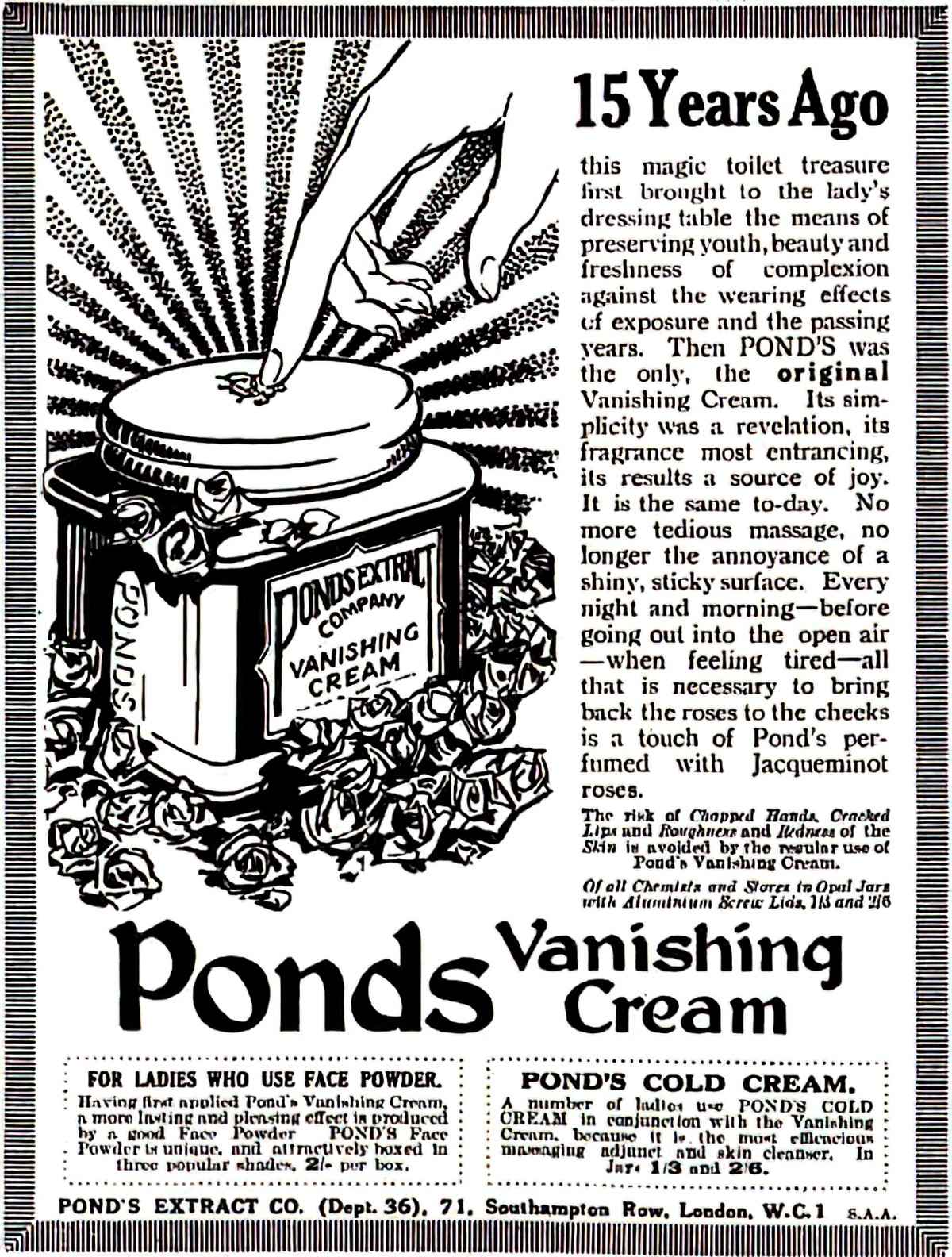

What else draws Rosemary to the box? She admires the creaminess of it. If we take a look at how beauty products are marketed, expensive solutions are frequently described as ‘creams’.

Cream and creaminess is a marker of youthful (white) skin, and prefigures how Rosemary will feel about the young girl who asks for a cup of tea outside.

Of course, today Rosemary would have the option of plastic surgery, facelifts and Botox. And when I say ‘option’, I don’t really mean option, because decisions aren’t made in a vacuum. Beauty standards vary between different social groups. Many wealthy women are expected to chase eternal youth via surgical interventions. Marriages become precarious when wealthy husbands can attract much younger women, despite getting old themselves.

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

As mentioned above, this is your classic rich-poor-divide story.

“A Cup of Tea” is also about a power dynamic between a wealthy husband and wife. The wife belongs to a class of women who, ironically, because of their wealth, have even less autonomy than women from the working class, who are typically more in control of their own (meagre) incomes than daughters of the upper class. Rosemary’s only real currency is her ability to act coquettishly. Her main job in life is to be a human lapdog, which becomes more and more difficult the older she gets.

THE EMOTIONAL LANDSCAPE

Rosemary doesn’t have the emotional intelligence to understand what drives her own self, though everyone around her sees it. Others use this knowledge to their own advantage.

For instance, her husband Philip understands how to get rid of the waif from his house. He only need point out the girl’s beauty. Youthful, natural beauty is his pretty-but-not-beautiful wife’s Achille’s heel.

The shopkeeper knows exactly which items Rosemary will like, then sells them to her at a sum perfectly pitched at Rosemary.

Even the girl in the street outsmarts Rosemary by a country mile. For one thing, she knows to hang around outside shops selling luxury (“antique”) items to women with a huge discretionary income. She knows not to ask directly for money; the upper classes find money crass, especially the women. So she asks instead for a cup of tea. Wealthy women are very used to providing cups of tea to their visitors.

On this particular day, however, the beggar girl gets more than she bargained for. She is about to get caught up in one rich woman’s morality drama, in which Rosemary plays philanthropist and saviour for an afternoon.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “A CUP OF TEA”

PARATEXT

THE TITLE

An episode from 2/13/21: George Orwell’s 1933 memoir of voluntary poverty, Down and Out in Paris and London, can still rip your heart out. Tonight, I read a few passages from it. Nobody has ever brought written about the reality of poverty as viscerally and sympathetically as him.

Human Voices Wake Us

SHORTCOMING

Rosemary has no real power aside from child-bearing and purchasing power. This puts her in a precarious position, despite the wealth she has married into (and which she presumably grew up with, as well).

I’d like to draw your attention to a very old children’s story which Katherine Mansfield may well have read: “Rosamund and the Purple Jar“. Notice the similarity between the names Rosemary and Rosamund? There’s a chance Mansfield never read the 1796 story by Maria Edgeworth, but I’d wager she did. The story remained in print until the 1930s. Few have read Maria Edgeworth now, or even heard of the woman, but her didactic stories for children were popular for over a century.

In Edgeworth’s story, a seven-year-old girl called Rosamund sees a purple jar at the shops and just has to have it. When she finally gets it, the jar is a huge disappointment. Rosamund learns that she should never have wasted her pocket money on such a thing.

Feels to me like Mansfield is writing an inversion of that, resisting the didacticism which child-aged Mansfield would have found condescending. (Think of the stories your great grandparents were reading. Imagine you’re still reading those. That would have been Mansfield’s experience of Edgeworth.)

Ironically, child Rosamund — a girl child of the late 1700s — had been given pocket money of her own! She was allowed to spend it as she pleased. “Rosamund and the Purple Jar”, didactic though it is, may has been read as an early feminist text, though I think it’s saying the opposite. Rosamund wasted her money, which sort of says girls can’t be trusted to make sensible purchases, don’t you think?

What about Mansfield’s Rosemary? At first glance, adult Rosemary is free as seven-year-old Rosamund to spend “pocket money” as she wishes, but Mansfield doesn’t try and crack on this is anything like real power. She avoids didacticism (a feature of Modernism) and she will leave readers to observe how Rosemary goes about getting what she wants, or what she thinks she wants.

DESIRE

Rosemary thinks she wants a pretty box. But in stories as in real life, people frequently go after one thing while really wanting something else. Marketers understand well: When we buy a product we are trying to satisfy an emotional need in ourselves.

What does Rosemary really want? To be pretty? Scratch that. That’s too simplistic for Mansfield. Rosemary wants to acquire prettiness. She has so little real empathy for a beggar girl, she treats her as an object, alongside the pretty box. (In fact, she’ll spend far more money on a box.)

“But,” said Philip slowly, and he cut the end of a cigar, “she’s so astonishingly pretty.”

“Pretty?” Rosemary was so surprised that she blushed. “Do you think so ? I—I hadn’t thought about it.”

“A Cup Of Tea”

Of course, the reader can see Rosemary is lying — to her husband, and also probably to herself. Earlier, before Philip entered the story:

“Won’t you take off your hat ? Your pretty hair is all wet. And one is so much more comfortable without a hat, isn’t one ? “

There was a whisper that sounded like ” Very good, madam,” and the crushed hat was taken off.

“And let me help you off with your coat, too,” said Rosemary.

“A Cup of Tea”

OPPONENT

A number of modern stories have delved into the theme of ‘female absorption of another’ (for lack of a better phrase). We might call it a type of cannibalism. A fairytale example would be the wicked stepmother and Snow White. These days, with better LGBTQIA+ literacy in audiences, similar dynamics tend to be read as sapphic. Women are presented as mortal enemies, yet they are actually in love with each other. Likewise, when Rosemary undresses the girl by taking off her outerwear, the tone is mildly erotic rather than motherly.

Rosemary Fell would like to inhale, cannibalise, absorb the pretty young girl who dares ask for a cup of tea.

PLAN

The husband, Philip, seems to know exactly how his wife works. If he would like to get rid of the waif, he only need signal to his wife that he, too, has noticed the girl’s beauty.

Can a girl ever really be poor if she is so very beautiful? Beauty is a form of currency. Cinderella stories suggest that beauty is all a girl needs and she’ll do just fine, economically.

Rosemary revises down how much help the beggar girl really needs.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Typically at this part of the story, someone almost dies. Either that, or someone spiritually dies. Note: It’s not always the main character:

The girl stood up. But she held on to the chair with one hand and let Rosemary pull. It was quite an effort. The other scarcely helped her at all. She seemed to stagger like a child, and the thought came and went through Rosemary’s mind, that if people wanted helping they must respond a little, just a little, otherwise it became very difficult indeed. And what was she to do with the coat now ? She left it on the floor, and the hat too. She was just going to take a cigarette off the mantelpiece when the girl said quickly, but so lightly and strangely : ” I’m very sorry, madam, but I’m going to faint. I shall go off, madam, if I don’t have something.”

“A Cup of Tea”

In this particular story, the main character learns nothing. Mansfield’s near-death scene, in which the beggar girl almost faints out of hunger, is a proxy for the awakening that should really be happening to Rosemary, if this were a fair and just world.

Notice the melodrama. Mansfield made use of a dropped coat on the floor to symbolise death. Wonderful imagery.

Back to fairies for a tick. Fairies are out of fashion so you may not know this unless you’ve read those very old fairy stories Mansfield was reading. Know this: If you ever get kidnapped to fairyland, DON’T EAT THE FOOD. Once you nibble at one of their treats or drink their potion THEY HAVE YOU FOREVER.

(Accepting any kind of gift from supernatural creatures will lead you straight into trouble. This moral is expressed in other folk tales. One notable example is The Elves and the Shoemaker, though contemporary retellings shift the message to a heartwarming tale of generosity.)

Mansfield has used the Fairy Queen archetype when creating Rosemary. Let’s go back to Rosemary’s ‘desire’ for a moment.

What does the Fairy Queen want?

The Fairy Queen wants to trap you. (Typically she tries to trap a man, though Mansfield was interested in relationships between women.) She will try to seduce you before revealing who she really is.

What does she want you? She wants to possess you, either by locking you up or by entering your very being, controlling your actions. But she doesn’t really want anything at all. She represents something you want, something you cannot articulate:

Her presence generates a desire without an object, or with an object that can exist only as further story. What if the Fairy Queen’s excessive and unruly desires are simply reflections, mirror-images of the insatiable desires she generates by her perpetual absence? What if her lust for man’s seed, for men’s bodies and blood, is a reflection of their desire for gold? For in these stories it is only the queen who is drive by lust.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

The Fairy Queen has the ability to turn scarcity into abundance, but she does not use this gift for good. She’s careful with her magic, using it only to gain power for herself. She has a sociopathic disregard for others.

Fairies are all about nostalgia. They associate themselves with places and things that are disappearing due to a changing culture, and the queen of the fairies is no different. She wants things to stay the same. She possesses you because she sees the hero within, and your wish to ‘disturb the universe’.

BUT ISN’T THE FAIRY QUEEN BEAUTIFUL?

The story opens with an ambivalent assessment of Rosemary’s beauty, and by ‘ambivalent’, I mean she is both beautiful and not, depending on which aspect of her you happen to be observing at the time:

ROSEMARY FELL was not exactly beautiful. No, you couldn’t have called her beautiful. Pretty ? Well, if you took her to pieces

“A Cup of Tea”

Modern audiences are used to seeing a beautiful Fairy Queen in stories. We commonly see her as a Snow Queen, popularized by Hans Christian Andersen, and remembered thanks to the endurance of stories such as The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe and 101 Dalmations.

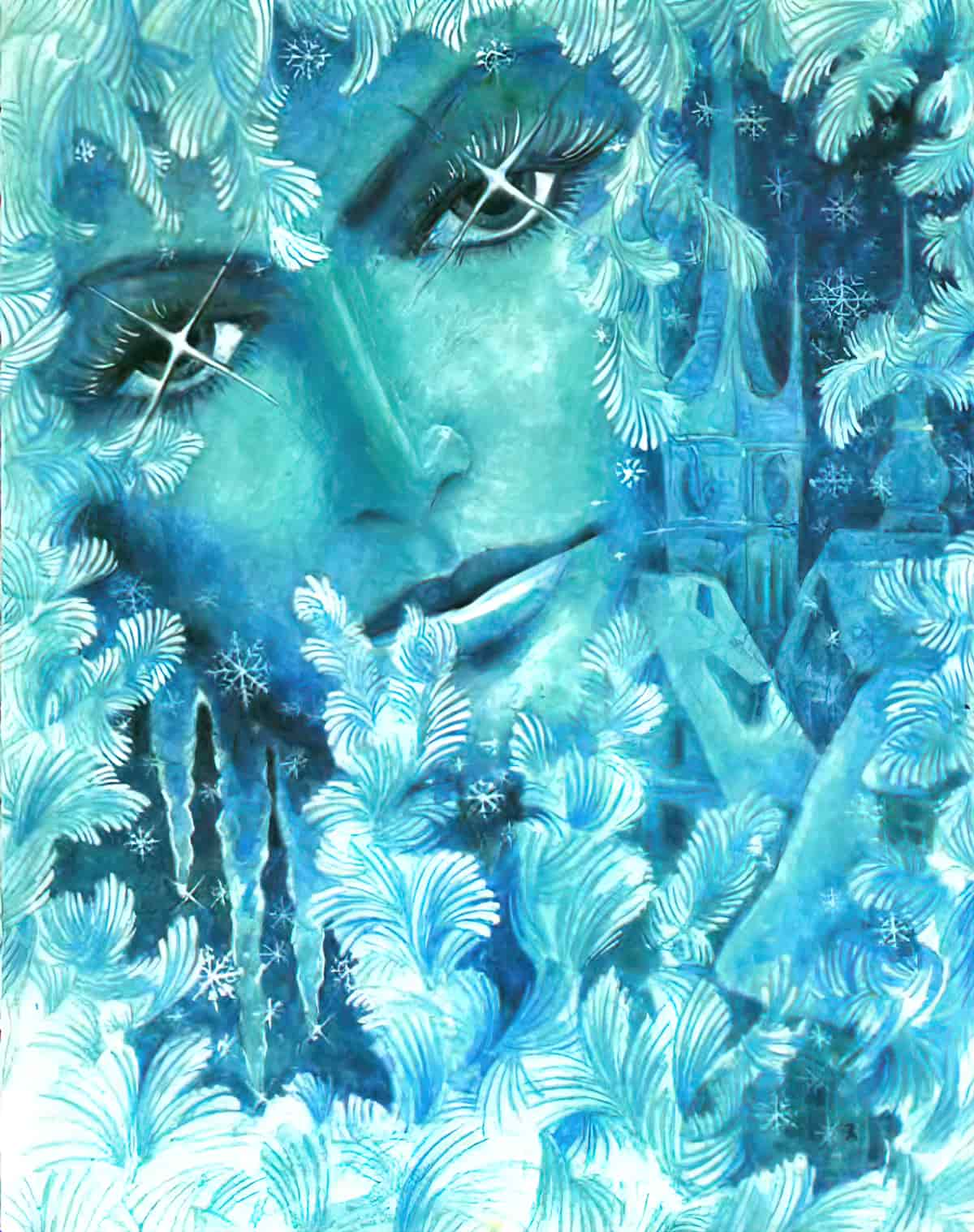

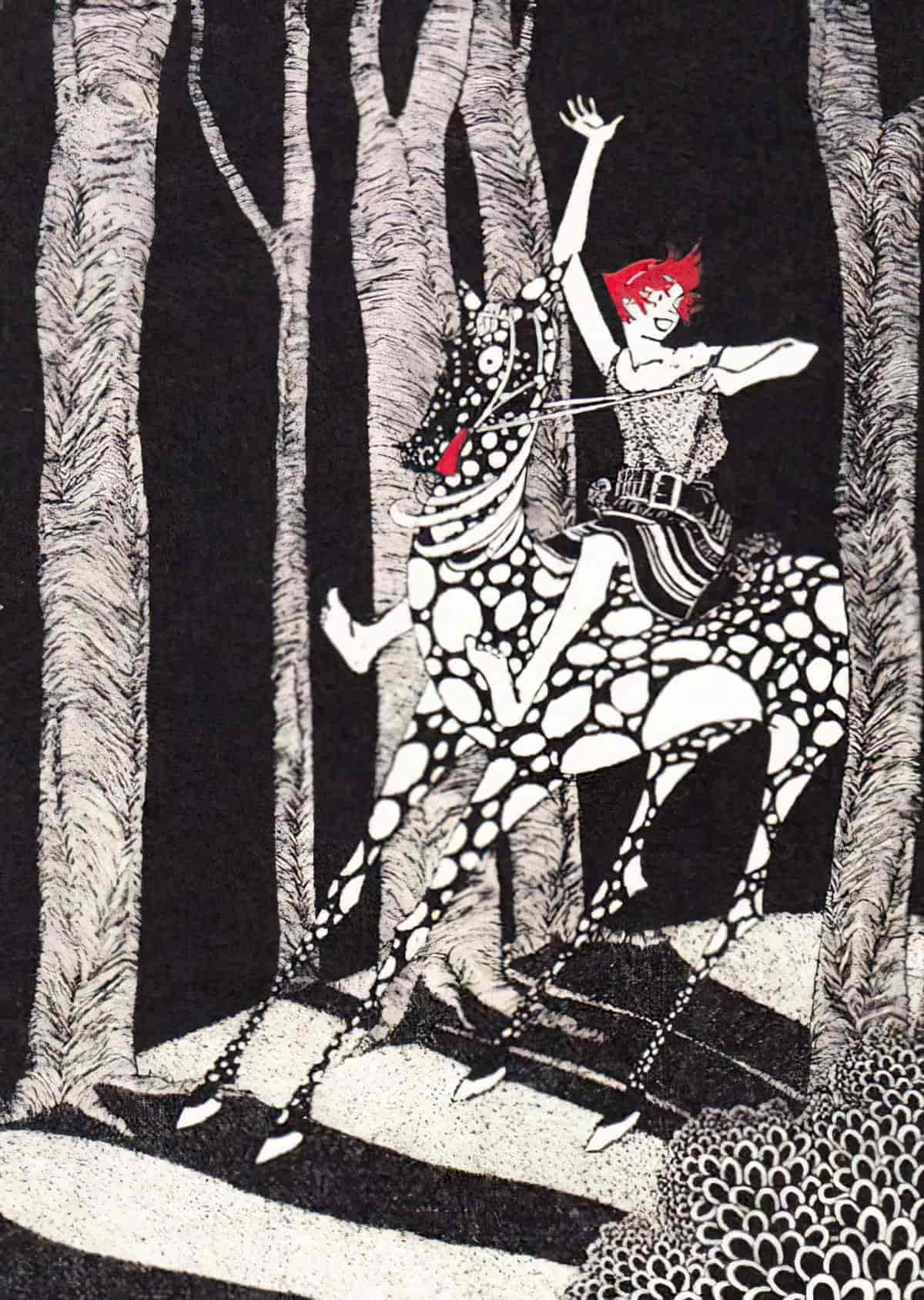

Below, various images of the Snow Queen as she abducts a child. In every instance, illustrators make her beautiful:

But audiences from antiquity didn’t have such a concretized mental image of what ‘beautiful’ looked like. As an example of that nebulous notion, the Hungarian version of the fairy queen is known simply as a ‘Beautiful Woman’.

A modern reading of any old fairytale is ridiculously binary and looks-ist; beautiful people are good people, especially when it comes to women and girls. I’m no fairy tale apologist, but it pays to remember that fairytale ‘beautiful’ was rarely described in specific terms. At most it referred to the colour of a girl’s hair or skin. (To add to the problems, ‘fair’ has come to mean ‘beautiful’ for racist and classist reasons.)

Before the 18th century, someone with teeth, a full head (and pubic area) of hair, and skin free of disfiguring sores counted as ‘beautiful’. If a good-looking young person today goes camping and comes back with a face covered in mosquito bites, is that person no longer beautiful? Perhaps not, but only temporarily. Any body ravaged by disease is wearing a kind of mask, separate from any true essence of beauty and goodness, which is how the fairytales meant it. The 20th century was an unusual period in human history because beauty was suddenly seen as fixed, changed only because of the ravages of old age. Since we all get old (if we’re lucky), fairy tale beauty is surprisingly egalitarian.

Katherine Mansfield’s life straddled the fin de siecle. “A Cup of Tea” is undoubtedly a commentary on what it meant for a woman to be “beautiful” in her lifetime.

Fast forward to the 21st century and we are losing this notion of natural born beauty, due to the popularity and accessibility of surgeries and other beautifying treatments. Interventions skip right over Mansfield’s era and give us more in common with a very old conception of beauty as changeable with effort and money (gold).

Katherine Mansfield created in Rosemary a fairy queen archetype described as both beautiful and not beautiful (‘pretty’). This supports my read of Rosemary as Fairy Queen, because the ancient fairy queen archetype is both beautiful and ugly, depending which side of us she wishes to reveal:

There is no sense that the queen of the fairies is really old, or bloody, or the author of castration and deformity. Rather, both beauty and deformity turn out to be appearances. Femininity is the instability of these appearances, their shimmering refusal to resolve themselves into a single stable object of desire.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

Women are commonly regarded as liars. One aspect of femininity held up as ‘evidence’ of devious charm: women’s use of make-up and other beautifying accoutrements, supposedly used to ‘conceal’ the uglier truth which lies beneath.

The modern conception is that a creature who shows her ugliness must really be ugly — the beauty was the mask. But for the ancient fairy queen, ugliness and beauty may both be masks, operating more like a two-faced Janus than like a mask. Neither version is more true than the other.

By the way, when the fairy queen appears in classic tales, pay special attention to her feet. Like many other fantasy creatures, her feet may give her away. She might have camel feet, or the trotters of some other heavy animal. (But to hide these feet she’ll probably be wearing a long, sweeping dress.)

ANAGNORISIS

Although I’ve compared the symbolism of “A Cup of Tea” to “Prelude”, as far as epiphanies go, this story is better compared to “The Garden Party” in which Laura, in her pretty hat and fancy party dress, delivers left-over food to a mother who has just lost her son in a terrible accident. Laura suddenly feels out of place as a rich girl who lives at the top of the hill. She seems to understand something, but Mansfield doesn’t tell us what.

Here we have another anti-epiphany, typical of Mansfield. It is far easier for Rosemary to forget she ever met the girl.

Is there an anagnorisis for the reader?

I think so, if readers are open to it. Don’t we all want to stay young and beautiful, pretending to ourselves that age — and therefore death — will never come for us? Mansfield makes use of the Fairy Queen archetype because she represents whatever you, the reader, cannot articulate.

Ergo, Rosemary cannot articulate it, either. Although it is Rosemary who is the Fairy Queen, she’s been deceived by others. She’s unaware of her own true desires. This leaves her (and us) in a dangerous position. When we don’t understand who we really are or what we really want, others may come to understand us better than we understand ourselves. This leaves us vulnerable to exploitation.

NEW SITUATION

Has Rosemary really forgotten the girl? She has absorbed the image of her. The girl may have even been of use in turning her husband on. While the husband basks in the glow of nubile feminine beauty, Rosemary can ask permission to buy the extravagant little box.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

I have no doubt Rosemary will return to the shopkeeper and buy the ornament for that exorbitant sum. The shopkeeper is the other man in Rosemary’s life who knows exactly how she works, and he will play her like a fine instrument.

Why does Rosemary need the box? Because the girl has gone and taken her beauty with her. The box is a compensatory beauty. Unlike Rosemary herself — and even the girl — the box will never grow old. The box will be creamy forever.♦

FURTHER READING

PODCAST RESOURCES

If you’d like to fall asleep, the Just Sleep podcast reads “A Cup of Tea” in the most calming boring voice imaginable.

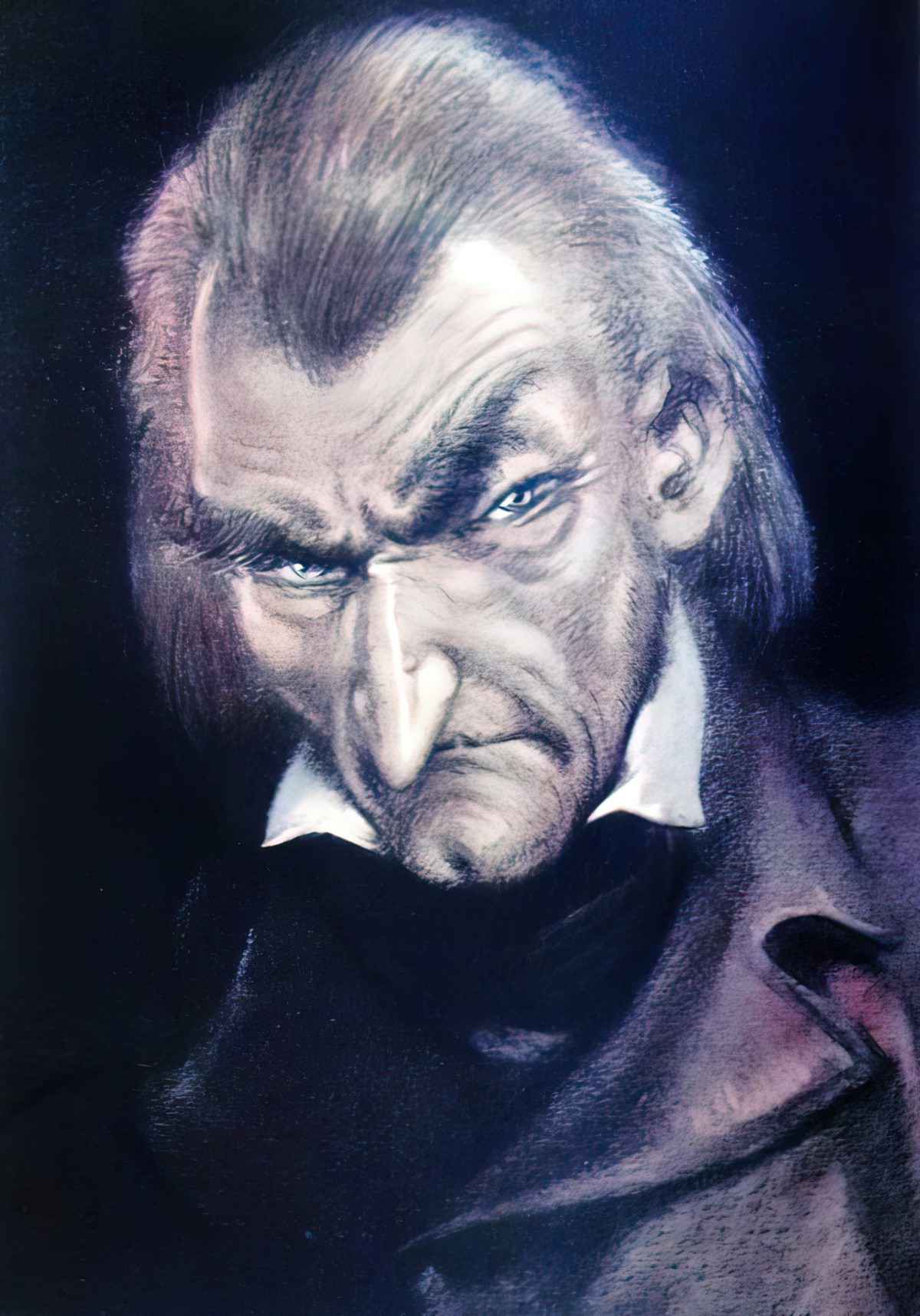

The CodeX Cantina podcast analyses “A Cup of Tea”. These guys point out that Rosemary is a different kind of rich selfish person than, say, Ebenezer Scrooge (who hoards and hoards) because she wants to be a philanthropist.

If you’d like to hear “The Snow Queen” read aloud, I recommend the retellings by Parcast’s Tales podcast series. (They have now moved over to Spotify.) These are ancient tales retold using contemporary English, complete with music and foley effects. Some of these old tales are pretty hard to read, but the Tales podcast presents them in an easily digestible way. “The Snow Queen” episode was published January 2019.

TEA

Tea has been one of the most popular commodities in the world. Over centuries, profits from its growth and sales funded wars and fueled colonization. Erika Rappaport talks about her new book, A Thirst for Empire, in which she delves into how Europeans adopted, appropriated, and altered Chinese tea culture to build a widespread demand for tea in Britain and other global markets and a plantation-based economy in South Asia and Africa. She shares her in-depth historical look at how men and women—through the tea industry in Europe, Asia, North America, and Africa—transformed global tastes and habits and in the process created our modern consumer society.

How Tea Shaped the Modern World

This week on A Taste of the Past, host Linda Pelaccio is joined by tea sommelier for the historic St. Regis Hotel in New York City, Elizabeth Knight.

Widely recognized as one of the country’s foremost authorities on tea and entertaining, Knight shares her passion as the founder of Tea with Friends, a website devoted to all things tea. A certified English Tea Master, she is the author of bestselling books on the subjects of tea and entertaining including Tea with Friends, Celtic Teas with Friends, Welcome Home, and Tea in the City New York – A Tea Lover’s Guide to Sipping and Shopping in the City.

Tea Time

It’s a little known fact that in the nineteenth century, Americans favored green teas consumed hot with milk and sugar. The teas were imported from China until Japan developed an export industry centered on the U.S. Author Robert Hellyer explores the forgotten American preference and traces the trans-Pacific tea trade from the eighteenth century forward in his book, Green with Milk and Sugar. He shares his insights on how the interconnections between Japan and the United States have influenced the daily habits of people in both countries.

Forgotten Past of Green Tea in America

It’s tea time babes, so grab yourselves an English muffin and turn on “Murder She Wrote”, because things are about to get real geriatric on this week’s burning-hot episode of America’s favorite podcast. We are talking tea history, tea puns, tea psychics and psychos, plus the glorious Long Island history of the Long Island Iced Tea, and the origin of no one’s favorite cocktail at the legendary Oak Beach Inn. So grab yourself an Arnold Palmer and pour it down your pants, it’s Life’s a Banquet the podcast!

TEA off! A double header episode about TEA! PART ONE

So you made it through part 1 of our TEASTRAVAGANZA. Congratulations, and welcome to part deux! We hope you brought some cream and some hottttt gossip! This week we talk hard tea, and the worst party in history, The Boston Tea Party. So get yourself some Smooth Move and toss it all into the ocean, it’s Life’s a Banquet the podcast!

TEA for 2- Part two of our TEAisode! PART TWO

Our guest is Don Mei who is the Director of Mei Leaf, an awesome tea company based in London.

Don also has a wonderful YouTube Channel called “Mei Leaf”, which has 80,000 subscribers. His videos are extremely educational and uniquely fun based on his extensive knowledge of both Chinese and Japanese tea. His global and analytical perspective helps viewers to appreciate tea even more.

In this episode, we will discuss various aspects of Japanese tea such as production, flavor and terroir in comparison with Chinese tea, Don’s intriguing path to become a tea specialist and much, much more!!!

What is the Difference Between Japanese and Chinese Tea?