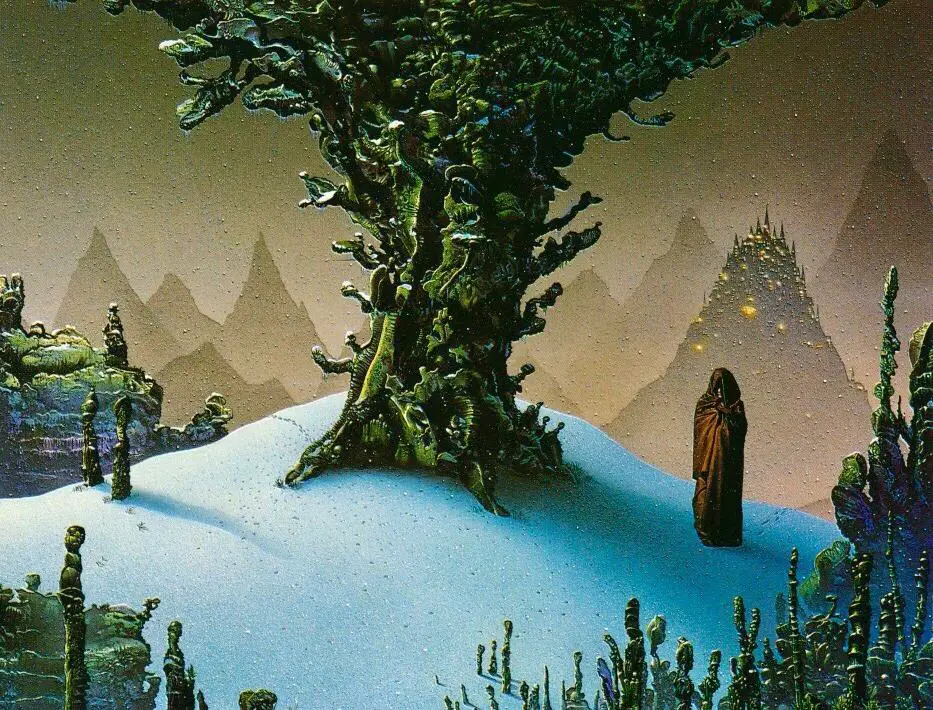

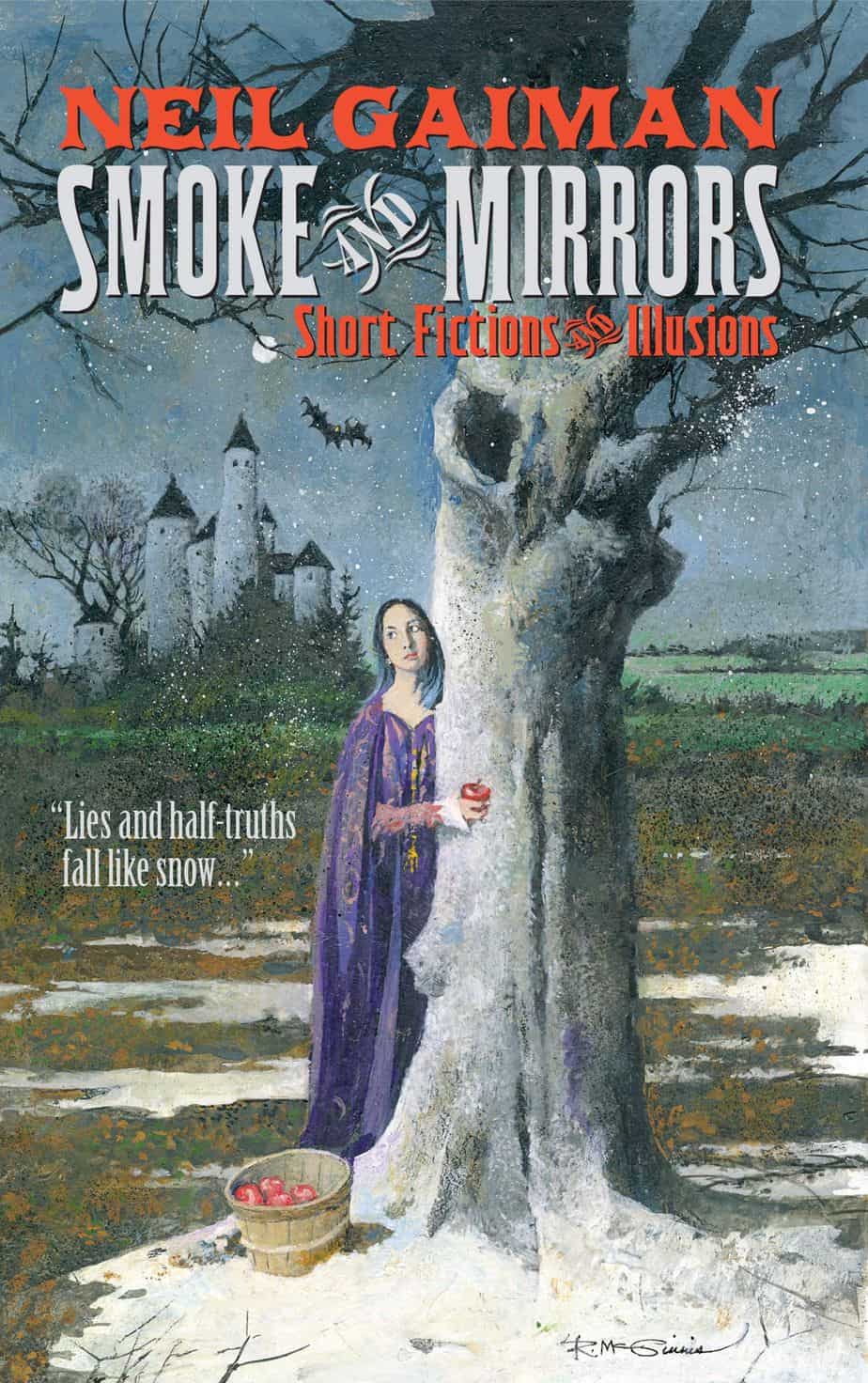

With their roots reaching deep into the earth, trees encapsulate the tense relationship of history and modernity. Many of Britain’s trees sprouted before the internet existed, before phones, TV or radio; some sprouted before cars, trains or newspapers. There are trees that predate the magna carta; Britain’s oldest tree (probably the Fortingall Yew in Scotland) could predate Christ by some 1000 years. Trees incite the imagination to connect to other worlds, and put human dramas in a longer historical perspective.

from the introduction to Weird Woods: Tales from the Haunted Forests of Britain

The film Get Out opens with an image of blurred trees, as if seen from a car window. This positions the audience right there with the characters, who are about to take a journey into your archetypal snail-under-the-leaf setting. Later, by lowering the camera close to the road, the trees seem to curve in on themselves, foreshadowing the claustrophobic, entrapped feeling. Sure enough, we even have a shot of a dead deer — if you remember Bambi from childhood you’ll recognise the dead deer as a symbol of vulnerability in the face of imminent death.

Here’s another creepy tree, this time from the film Tokyo Drifter. Some trees are comforting, other trees are creepy. What makes a tree (or trees) creepy, then? Can we put this particular creepiness into words?

The landscape that surrounds us is rich in folklore connected with the plants and flowers that dwell within it. Some of these are old and connect with the world of fairy. Some are more modern and relate to invasive species. All are fascinating. In this episode of the Folklore Podcast, storyteller and environmentalist Lisa Schneidau discusses the research which went into her book “Botanical Folk Tales of Britain and Ireland” and tells some of the stories related to our plant-based beliefs.

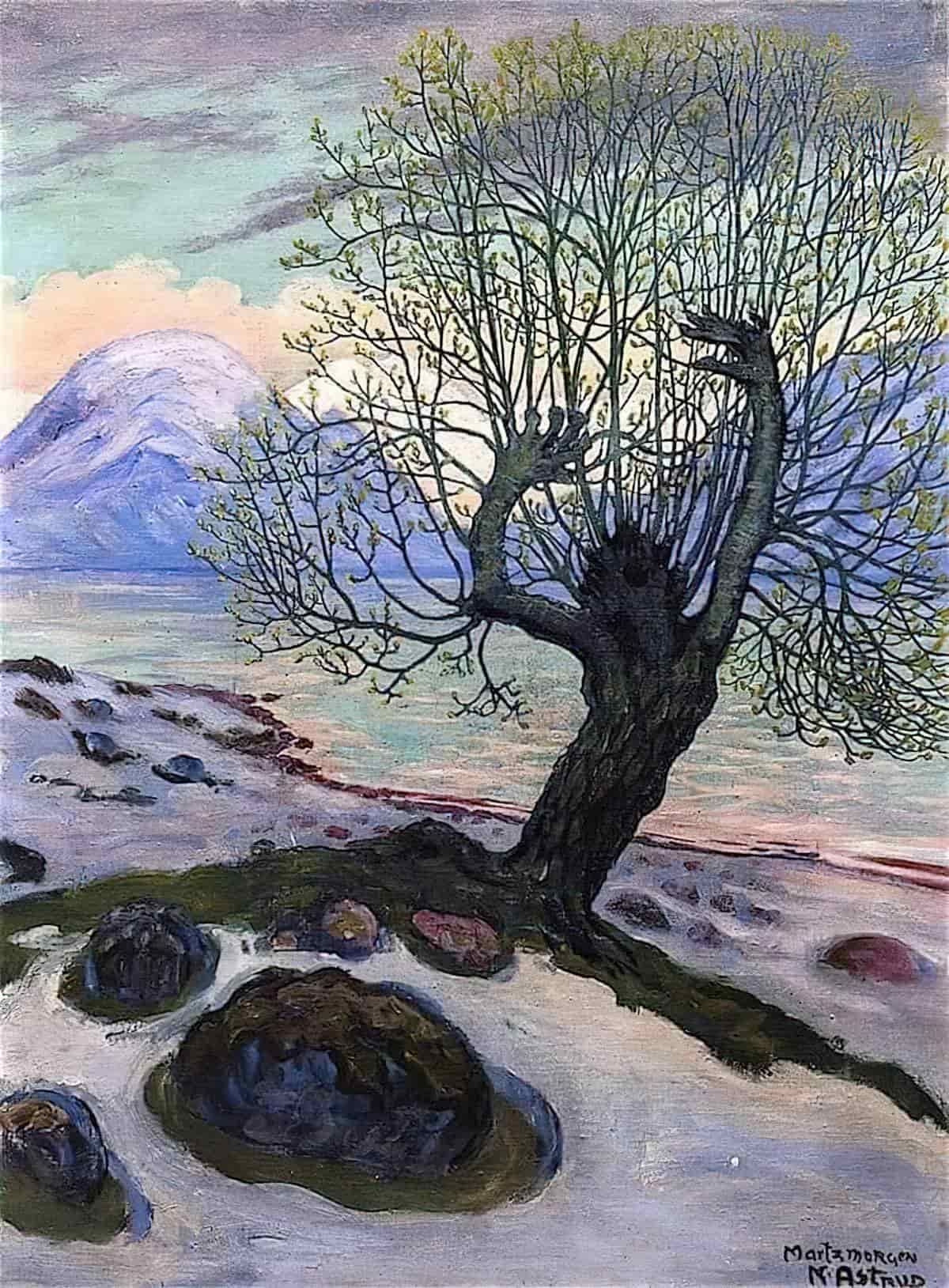

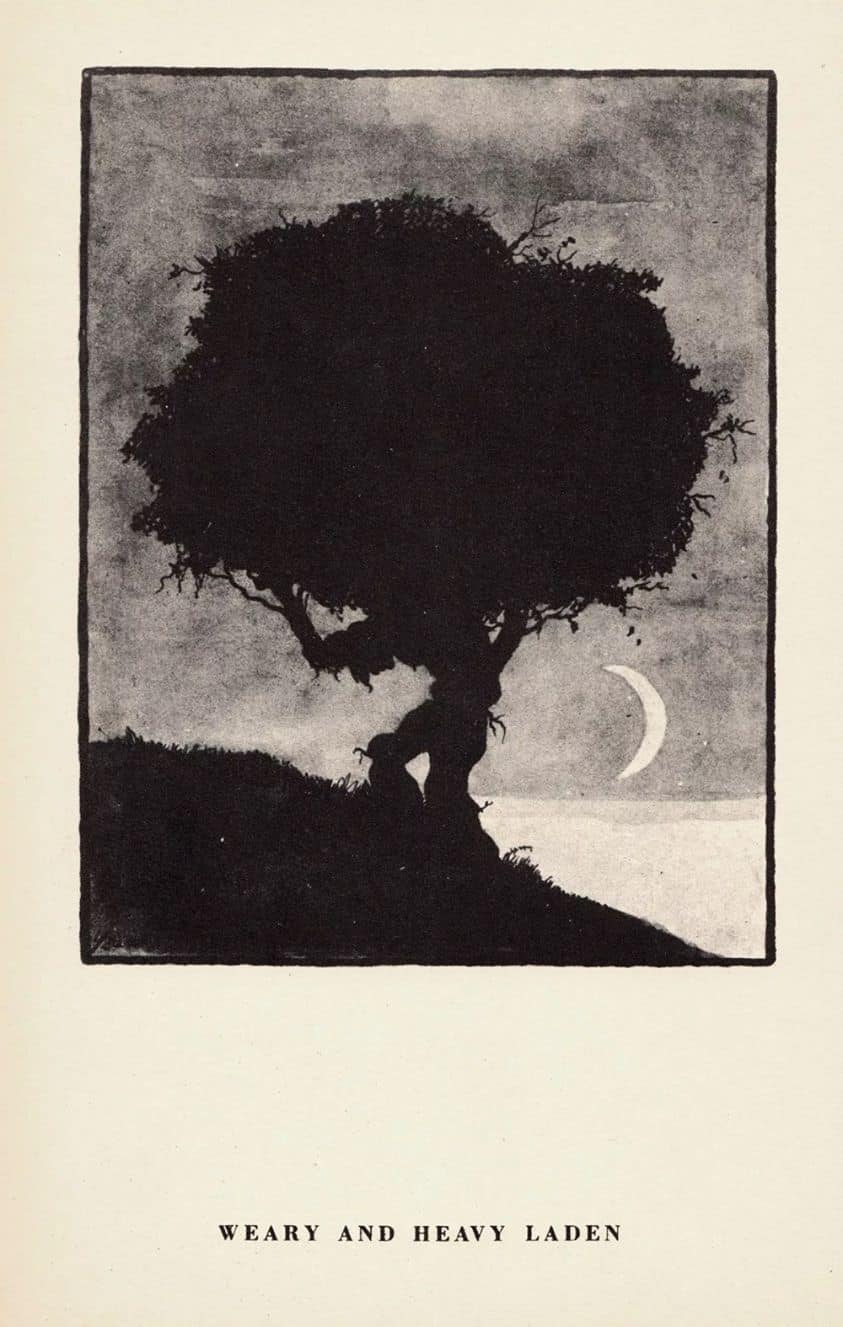

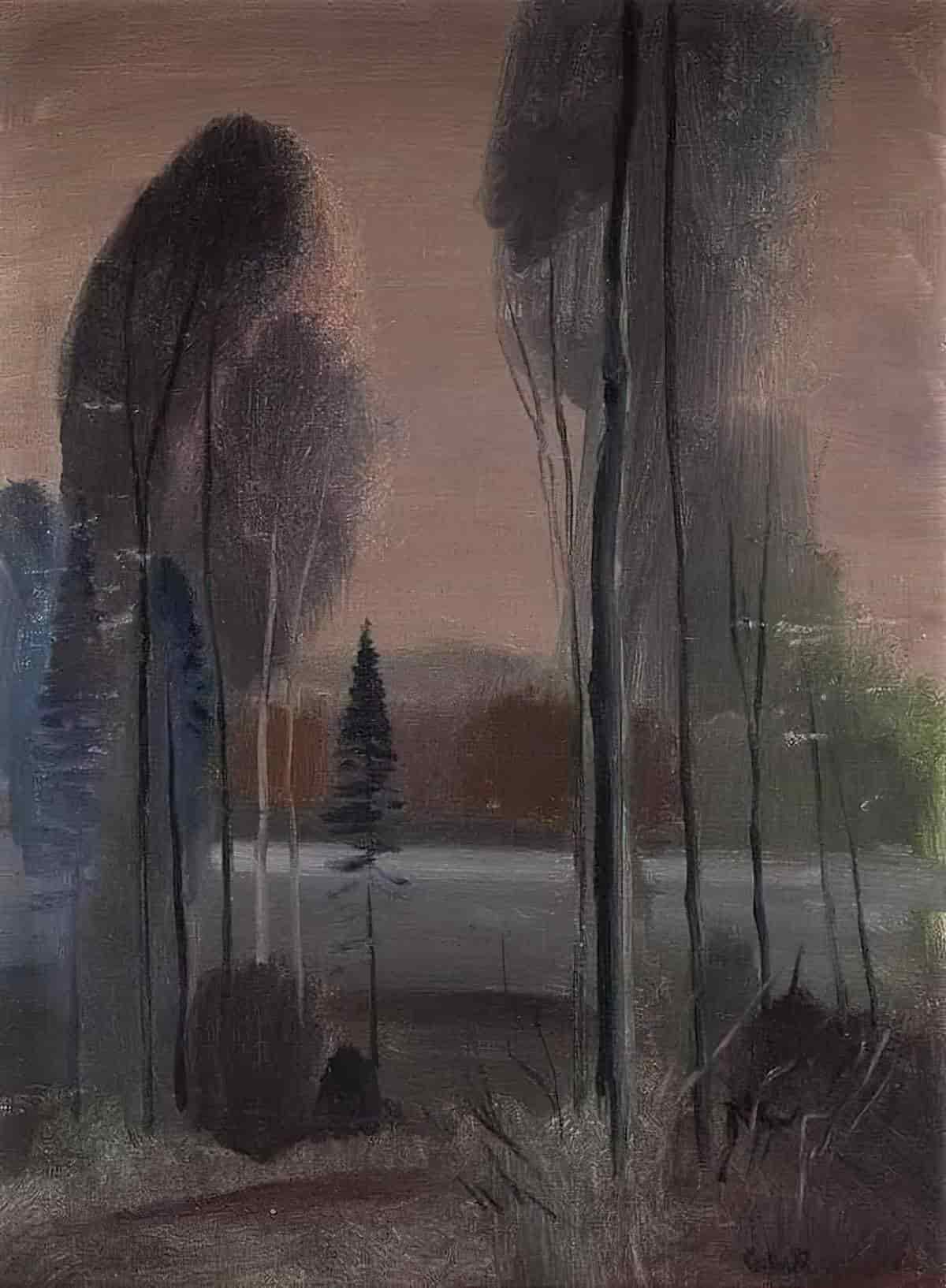

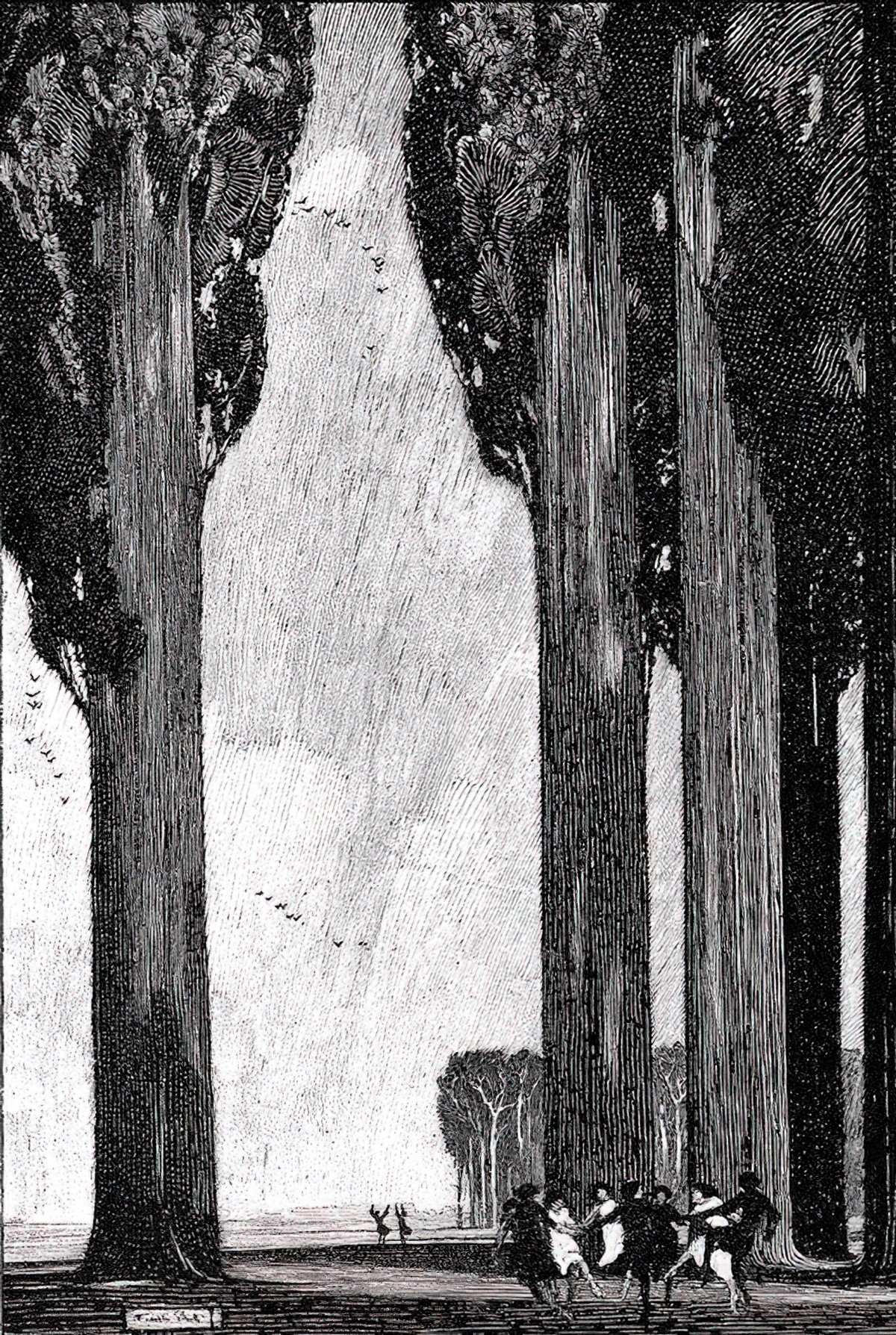

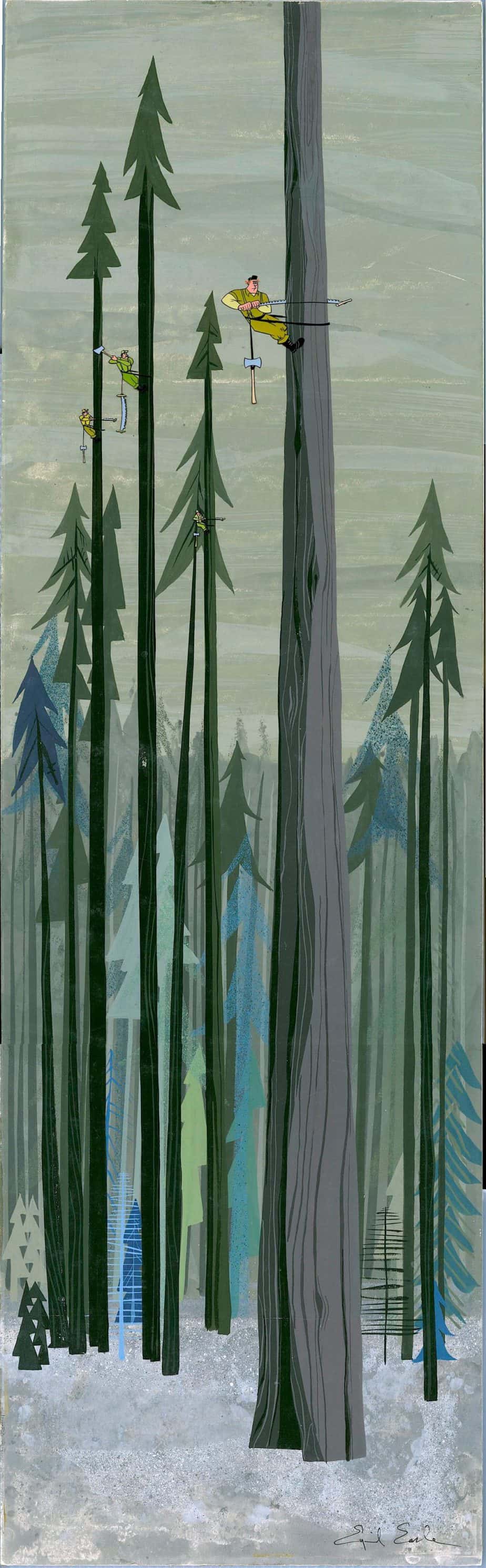

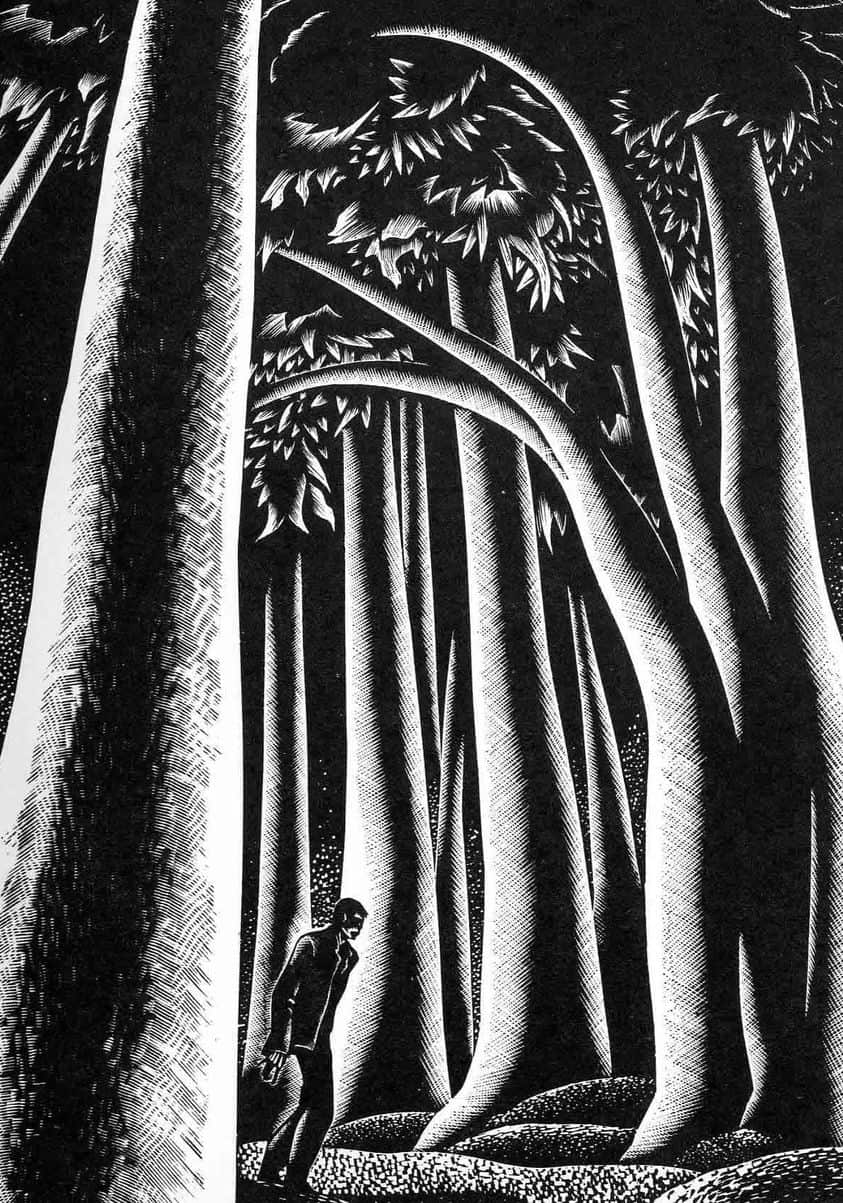

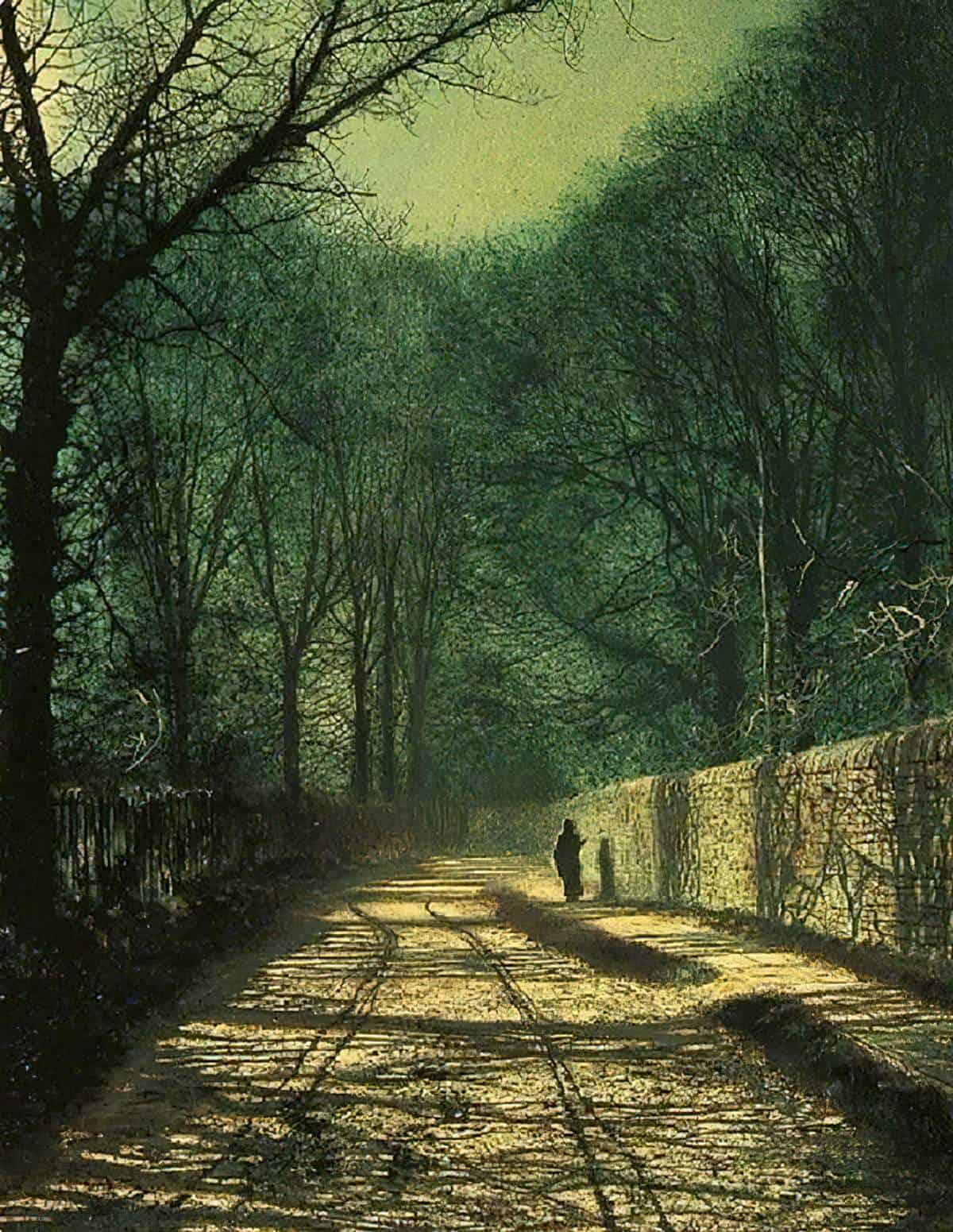

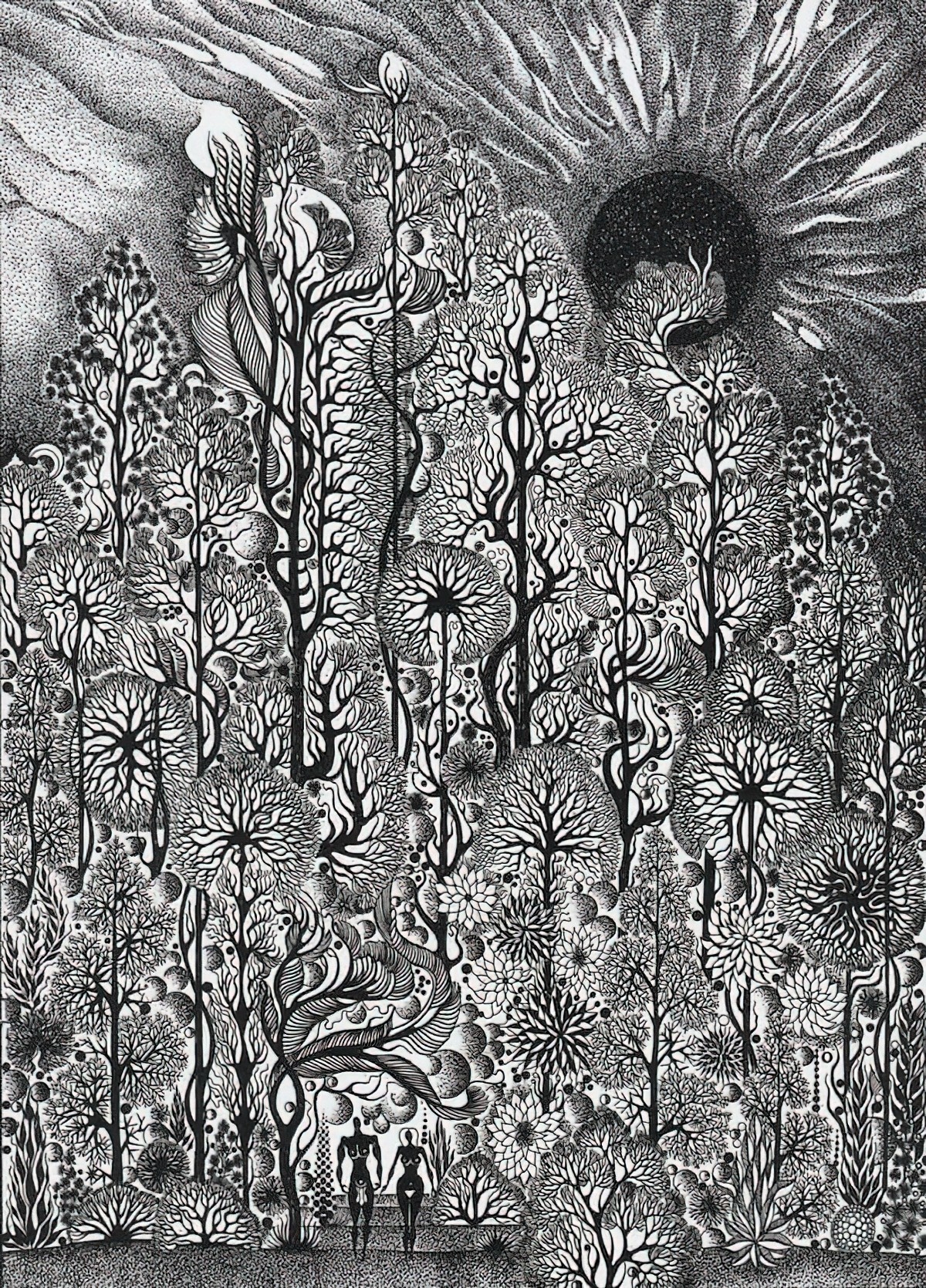

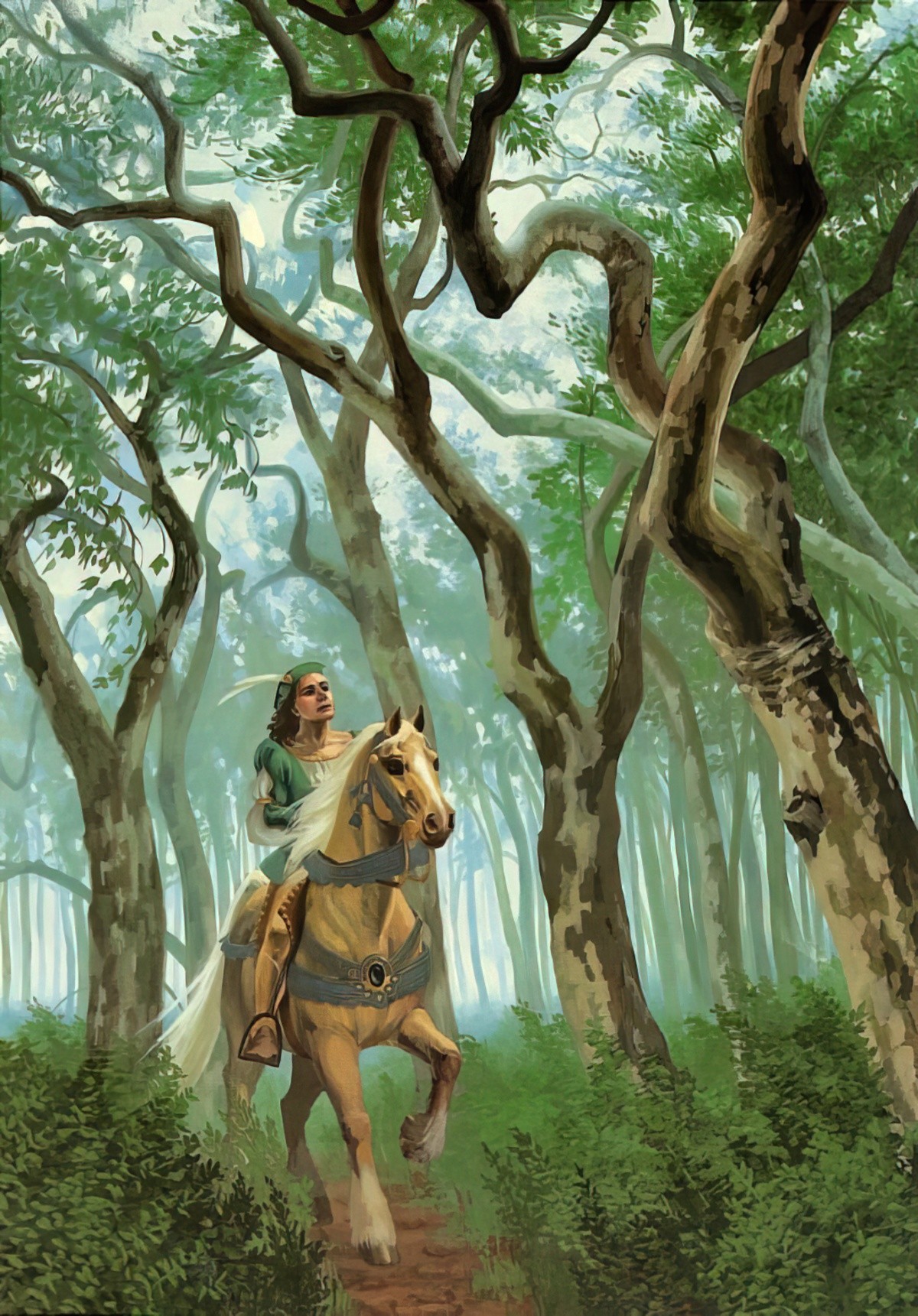

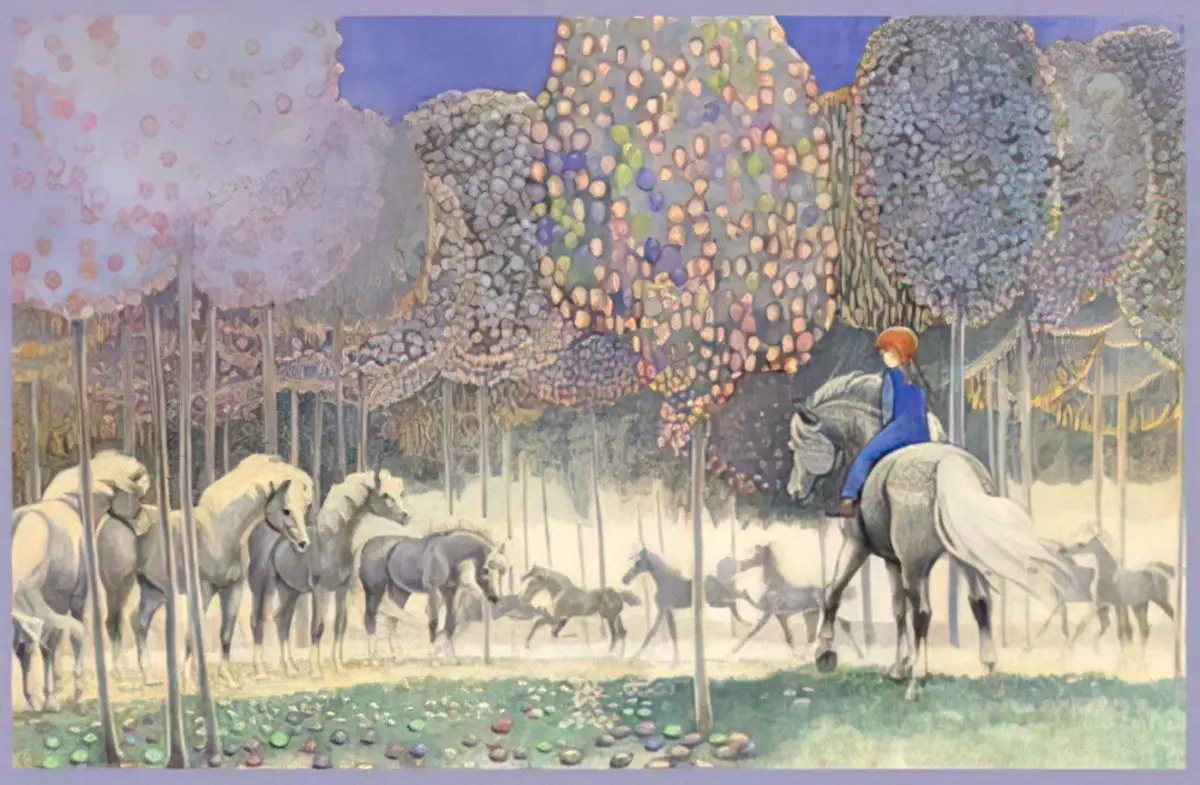

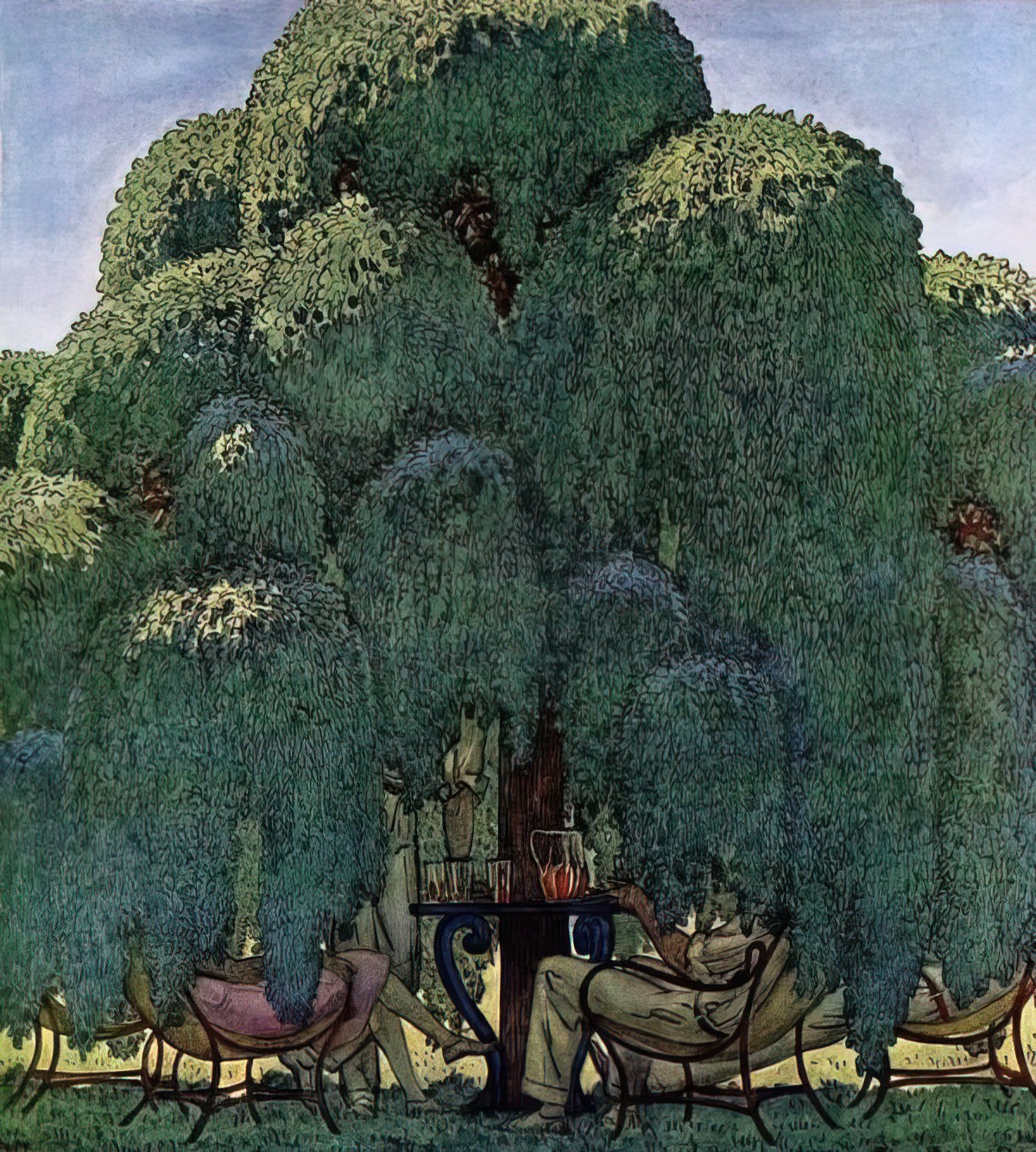

When artists utilise elongated landscape canvases, the height of trees can seem extra creepy. If we can’t see all the way up, what might those canopies be hiding?

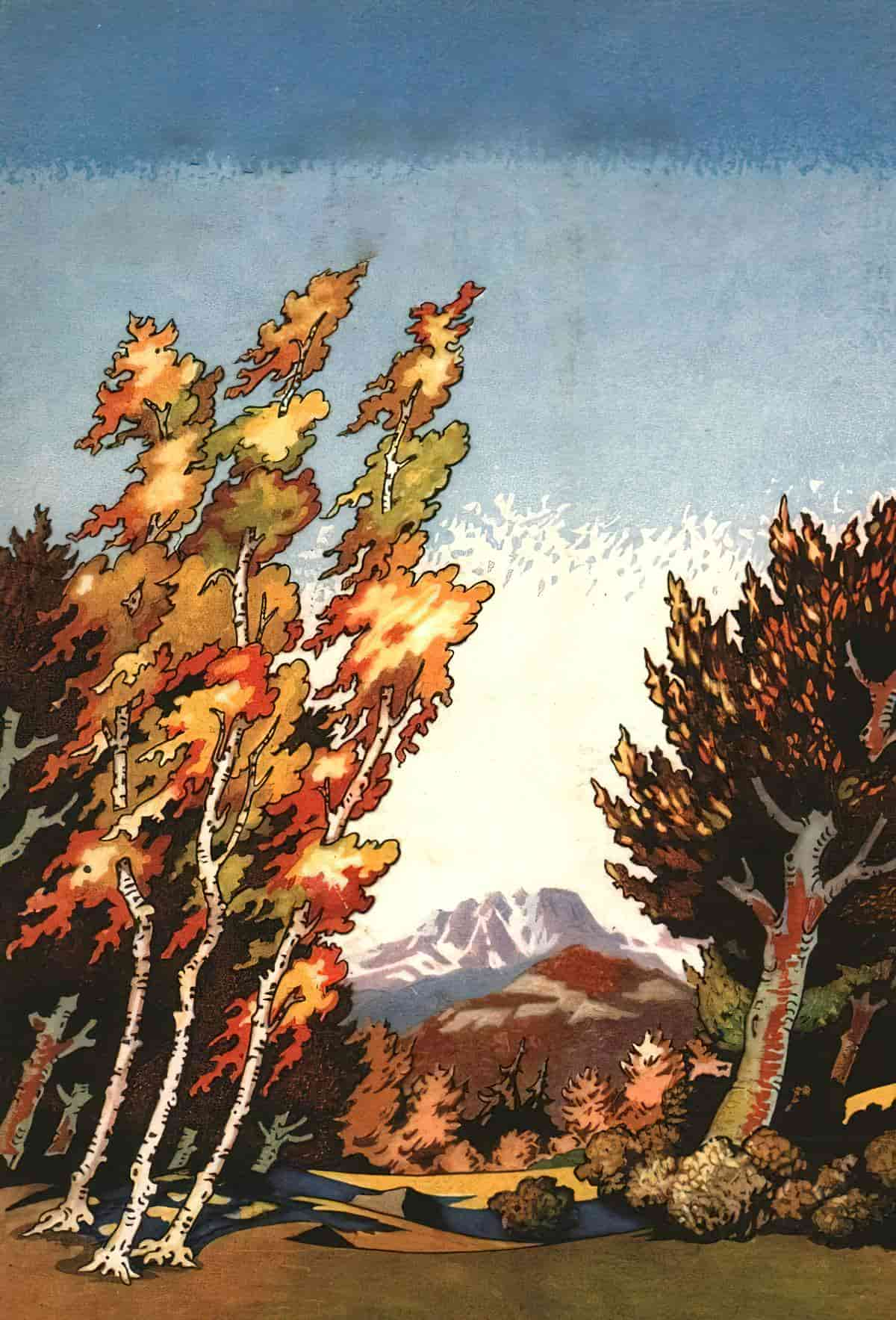

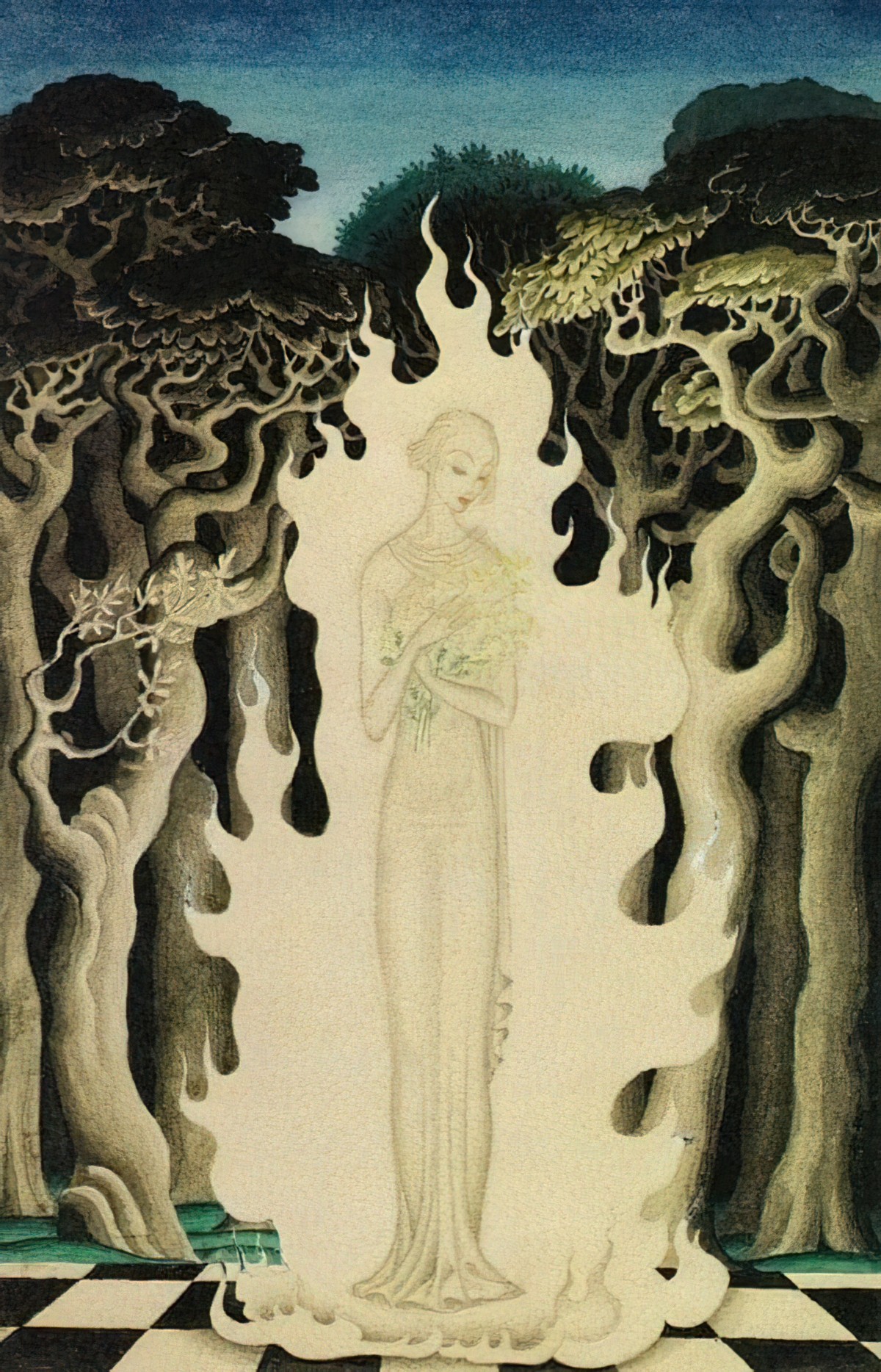

The trees of the illustration below are probably that way due to the wind, but the large trees on the right seem to lean towards the smaller trees on the left like monsters about to eat the smaller trees up.

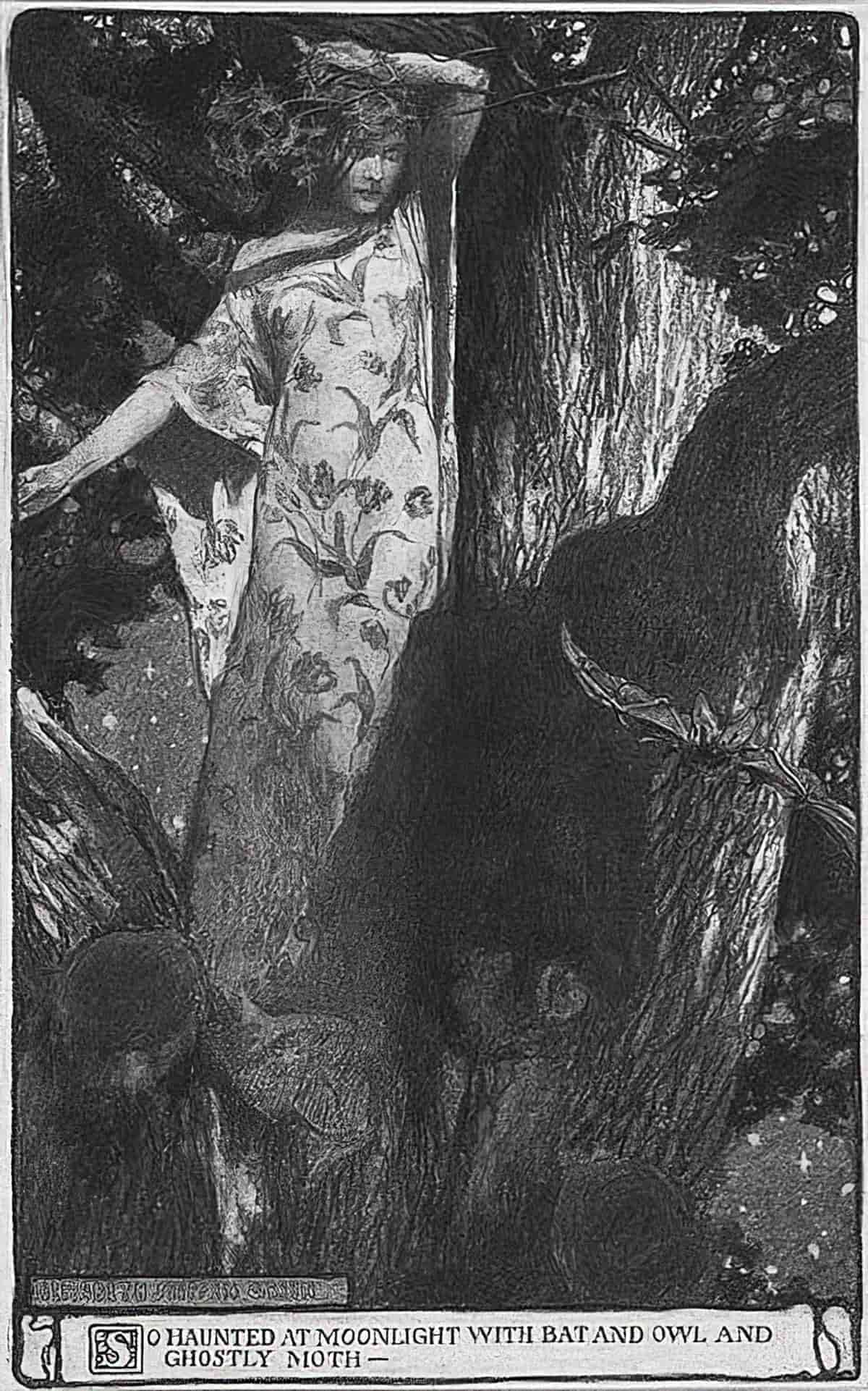

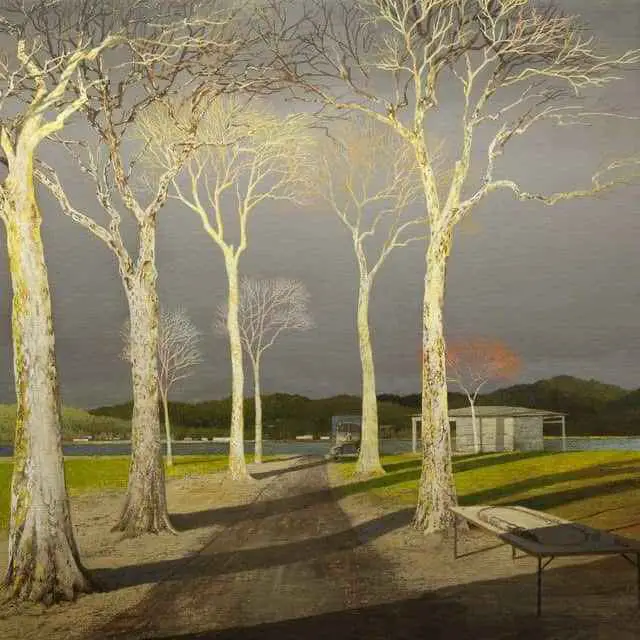

How to explain the creepiness of the trees below, illustrated by Alessandro Tofanelli? I believe it’s a mixture of spindliness, spacing and shadows.

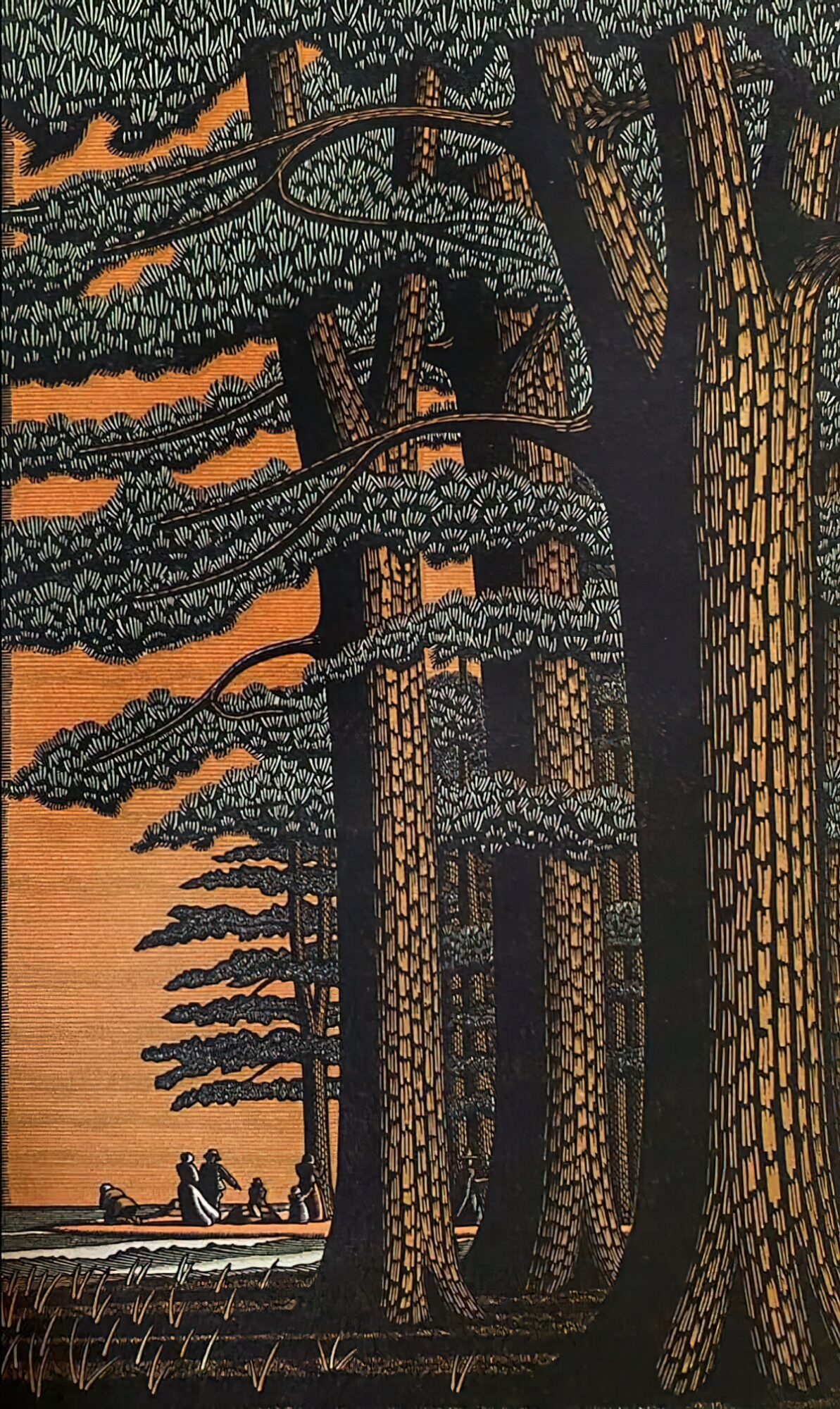

As in the painting above, this one below from 1778 utilises the horror corridor effect. (Corridors are commonly utilised in horror films. Lines of trees are the natural symbolic equivalent of corridors in architecture.)

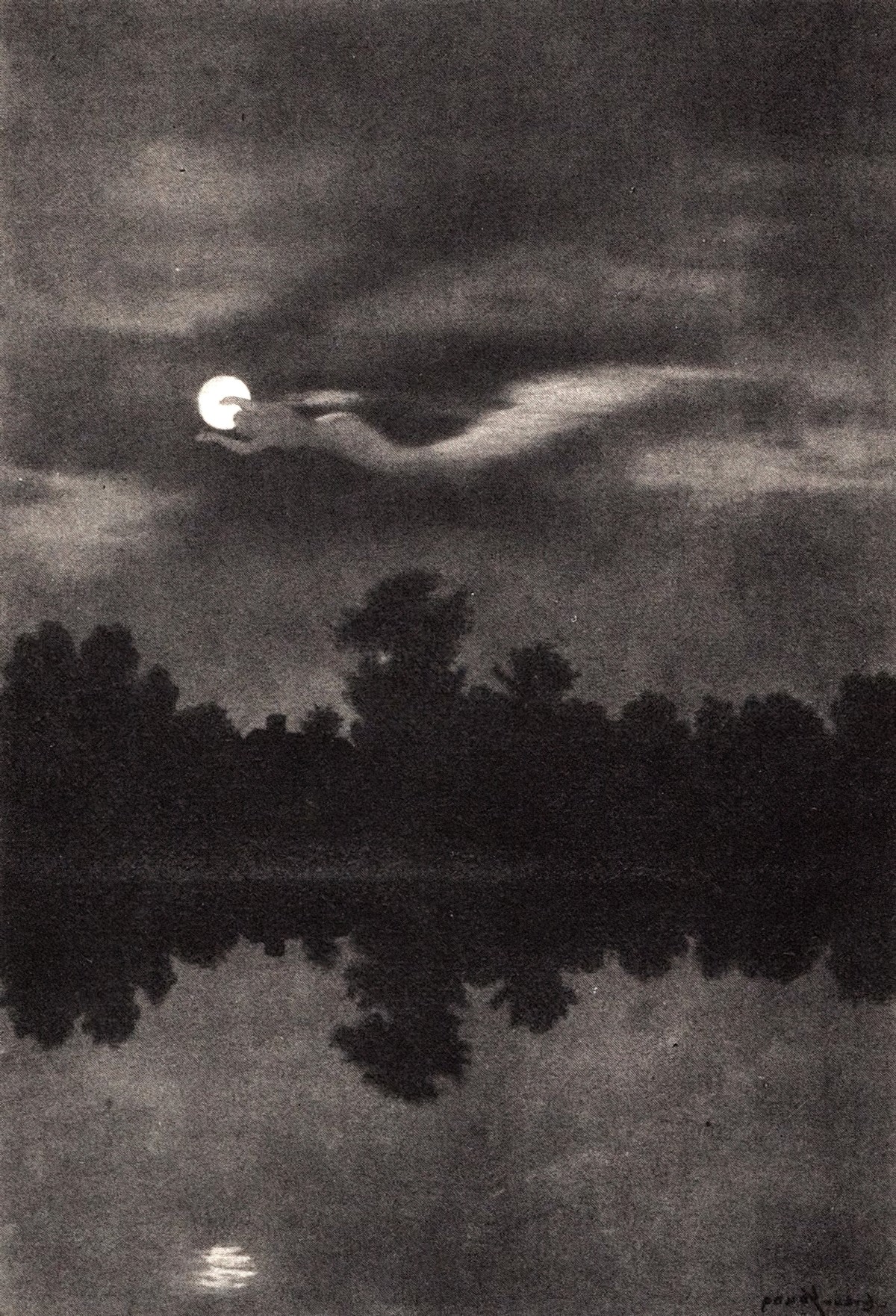

Symmetry in general can be creepy, especially when the symmetry is slightly off-kilter. Therefore, a line of trees along a mirroring lake gives off an ominous vibe, though I’m sure what’s happening in the sky is also part of the creepiness of the illustration below.

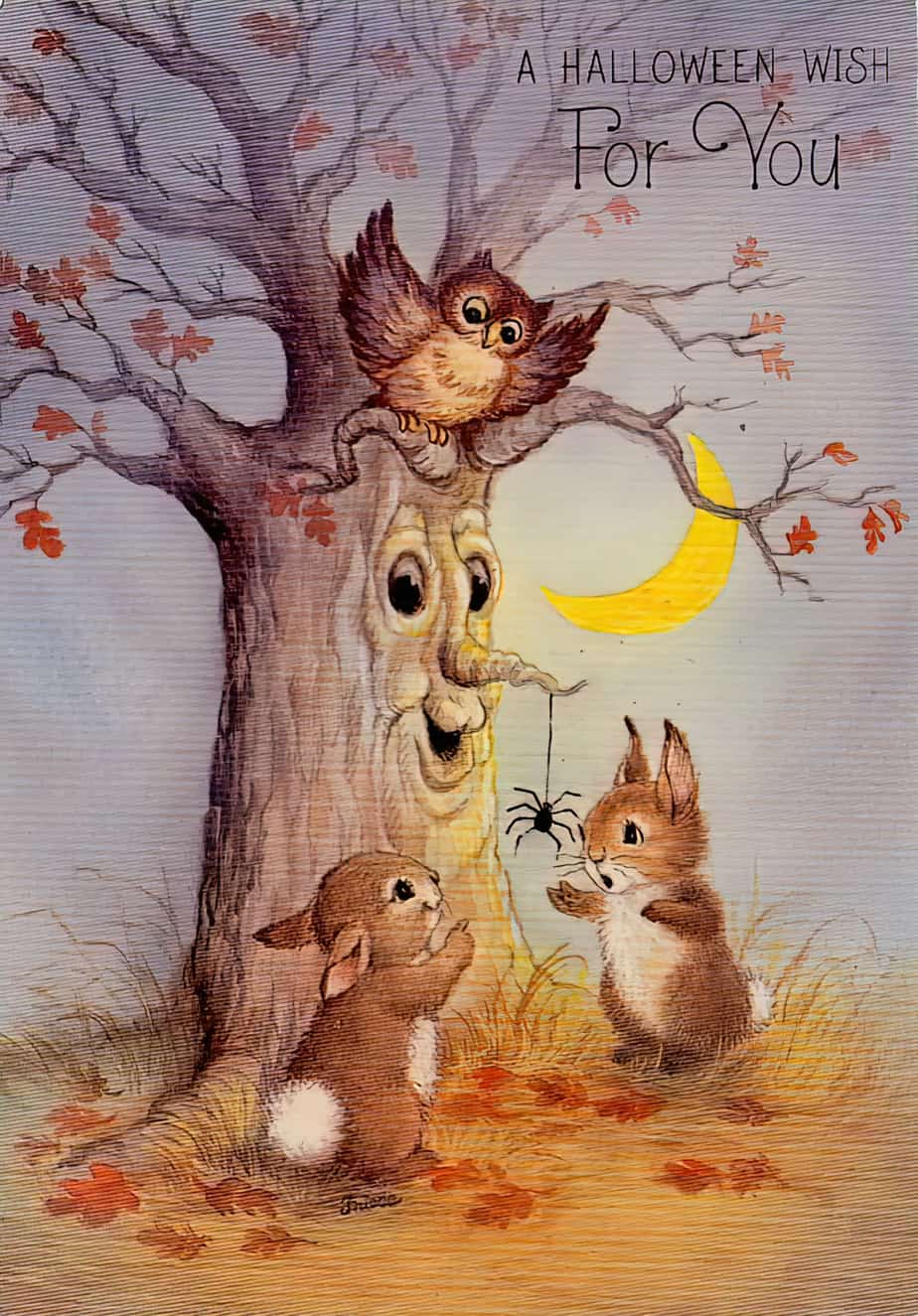

When we hear trees talking to us, that’s a pretty good sign of hallucination. It’s also a very common one.

THE FIRST HALLUCINATIONS I can remember from childhood are the faces in the trees. I saw them everywhere, especially at night. Whether they had a twisted laugh or demonic eyes, they were always scary. I have schizophrenia, and I still see the faces in the trees. I was diagnosed at age 20, and for the past 14 years, I’ve been committed to helping people understand what schizophrenia is—and what it’s not. These are the biggest misconceptions I tackle most often.

Top Ten Myths About Schizophrenia

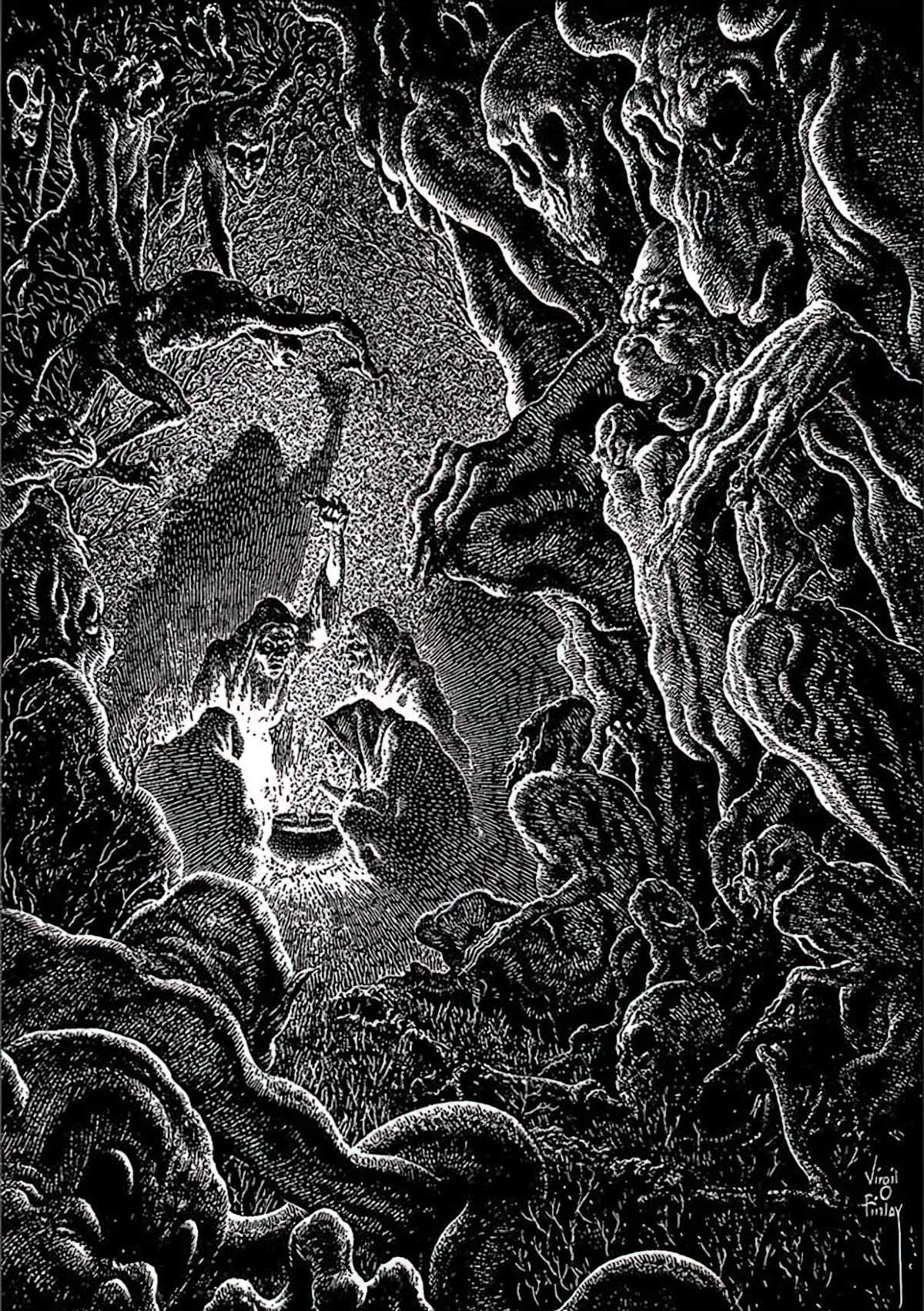

But all of us are prone to seeing faces in things, and this includes trees.

Spindliness is clearly scary. Look at Tim Burton movies to know that. Are spindly trees creepier than leafy trees because of the symbolism of winter, which is in turn connected to death? A winter deciduous tree is almost indistinguishable from a dead tree, after all. There’s also the zombie effect of a bare, deciduous tree ‘coming back to life’ in spring. Humans are wary of anything which seems to spring back to life. (I use the verb ‘spring’ mindfully there.)

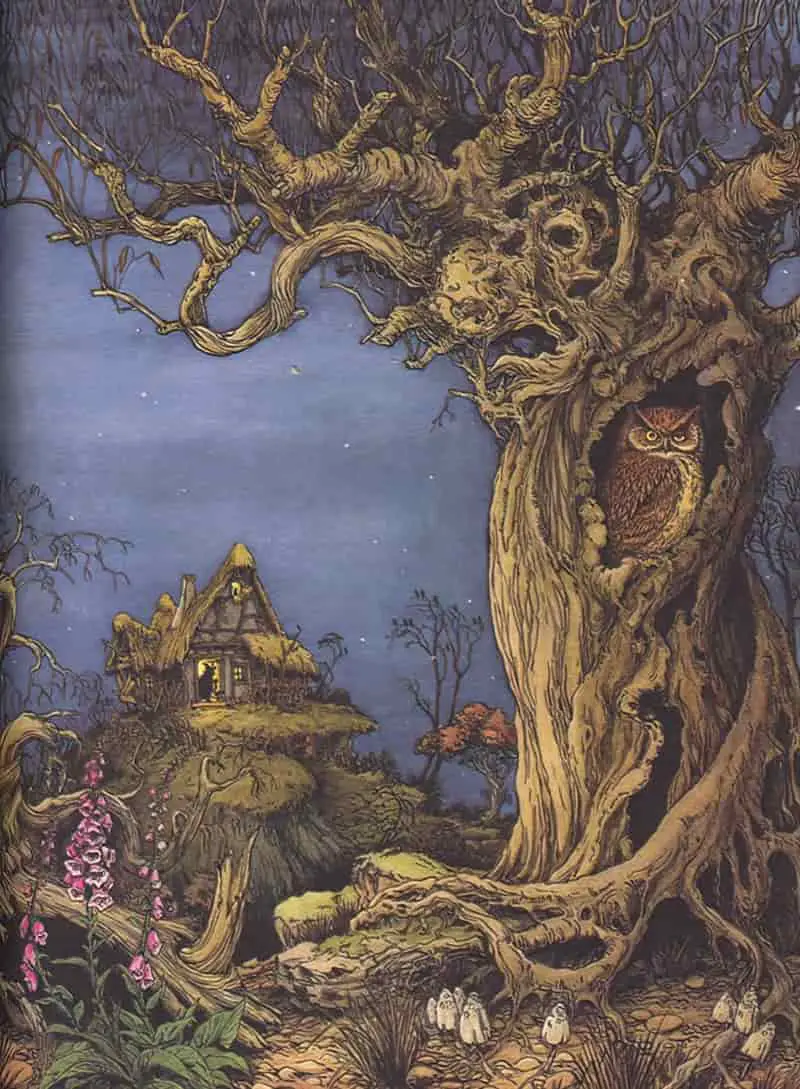

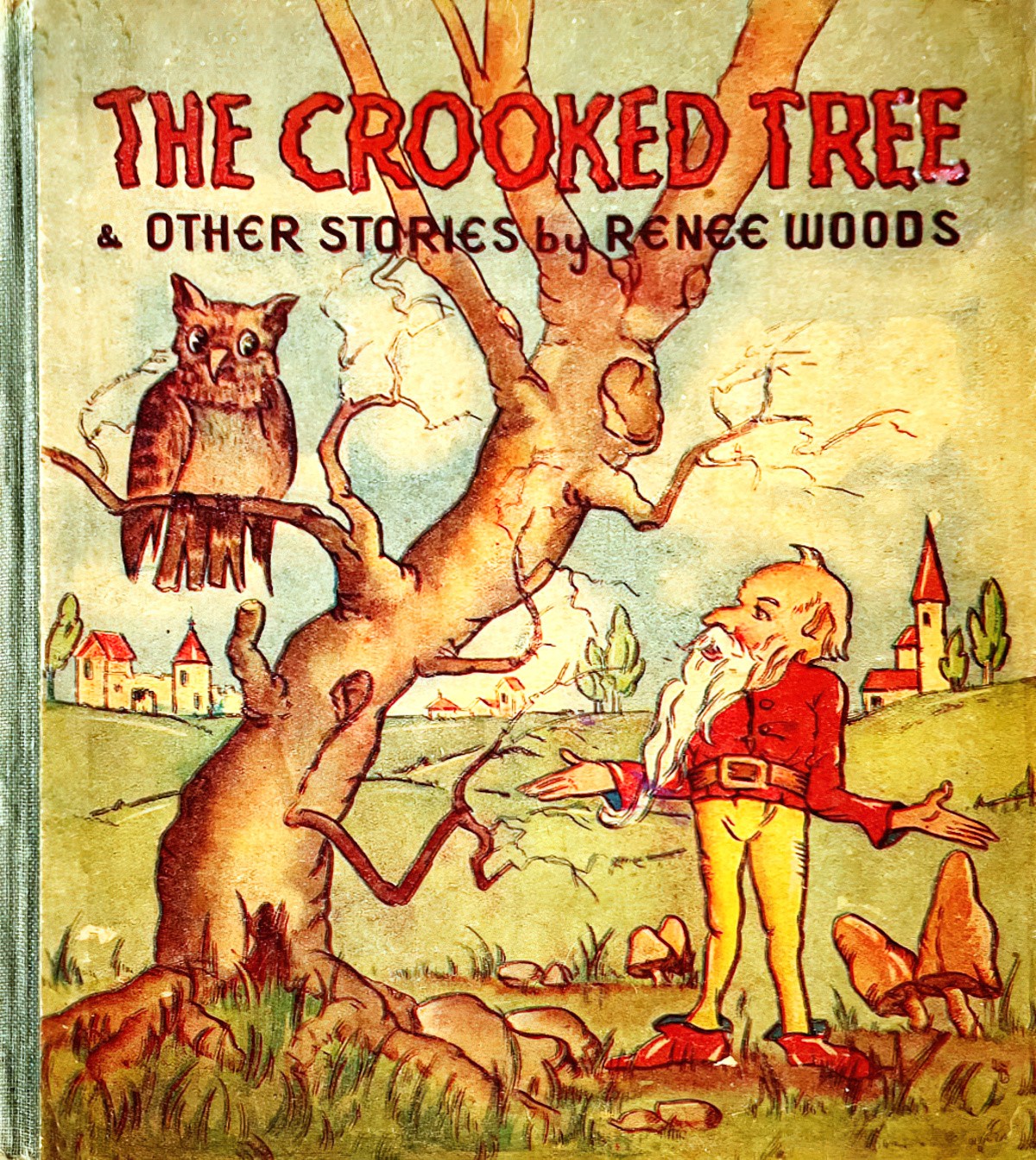

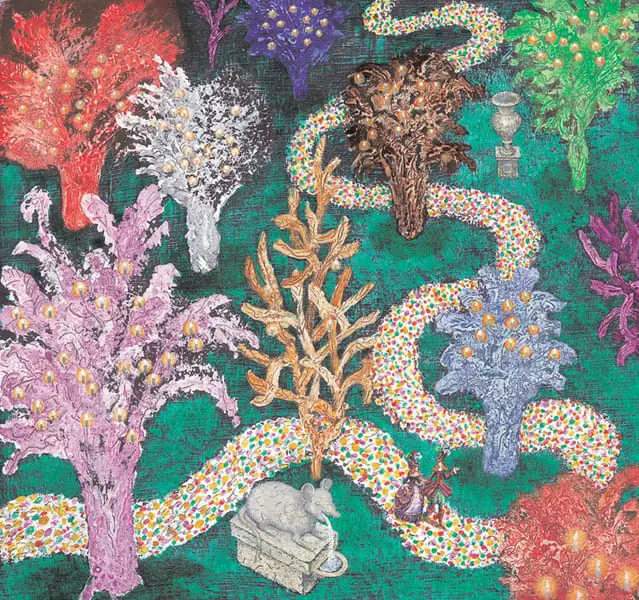

There’s spindly, then there’s ‘oddly shaped protrusions’ of the fantasy tree.

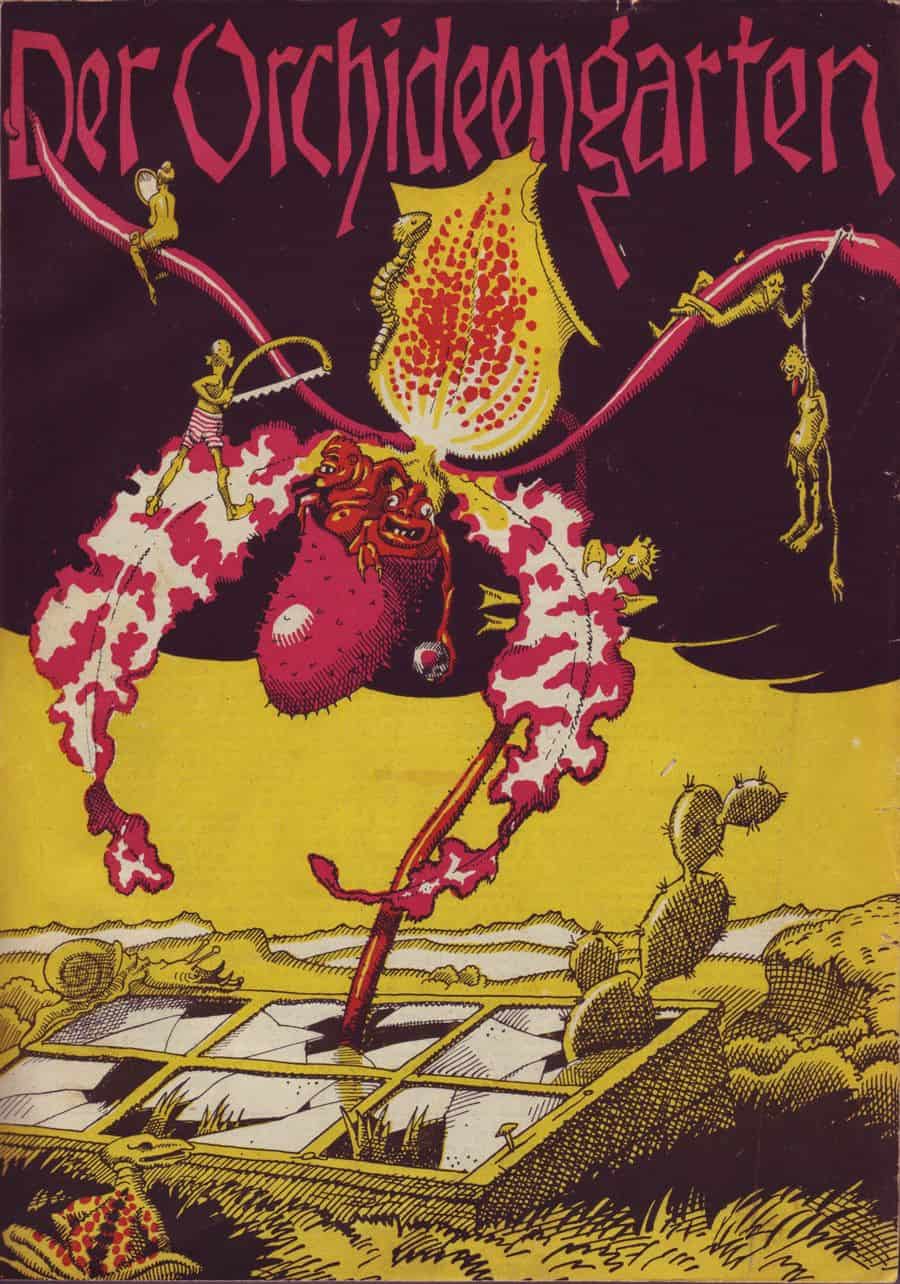

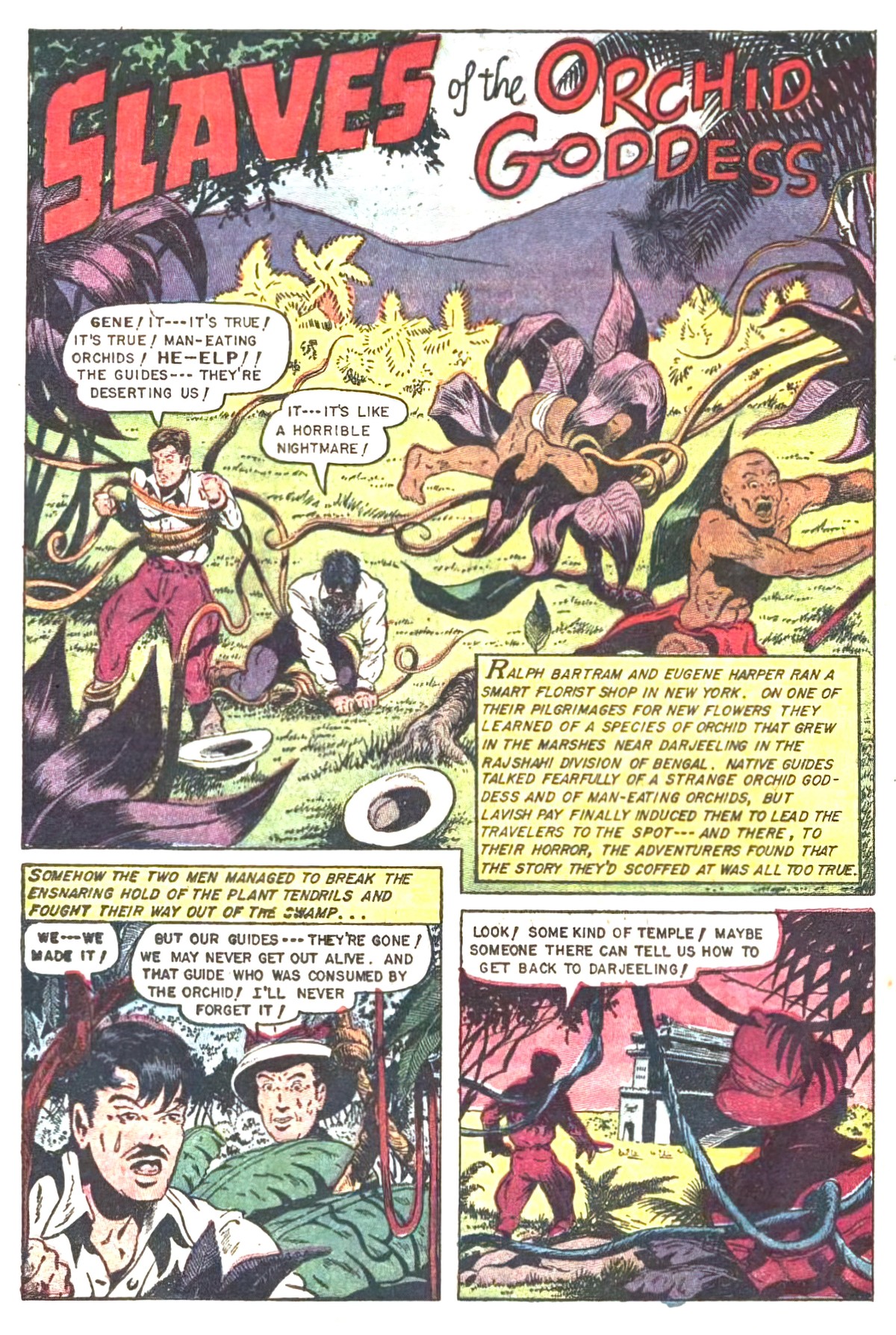

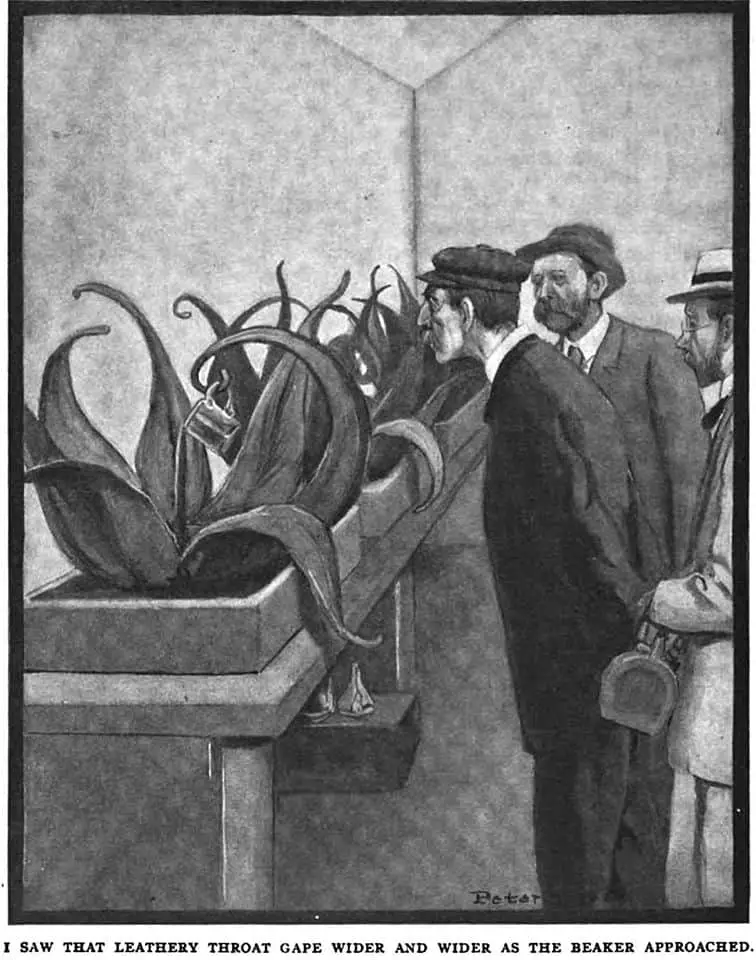

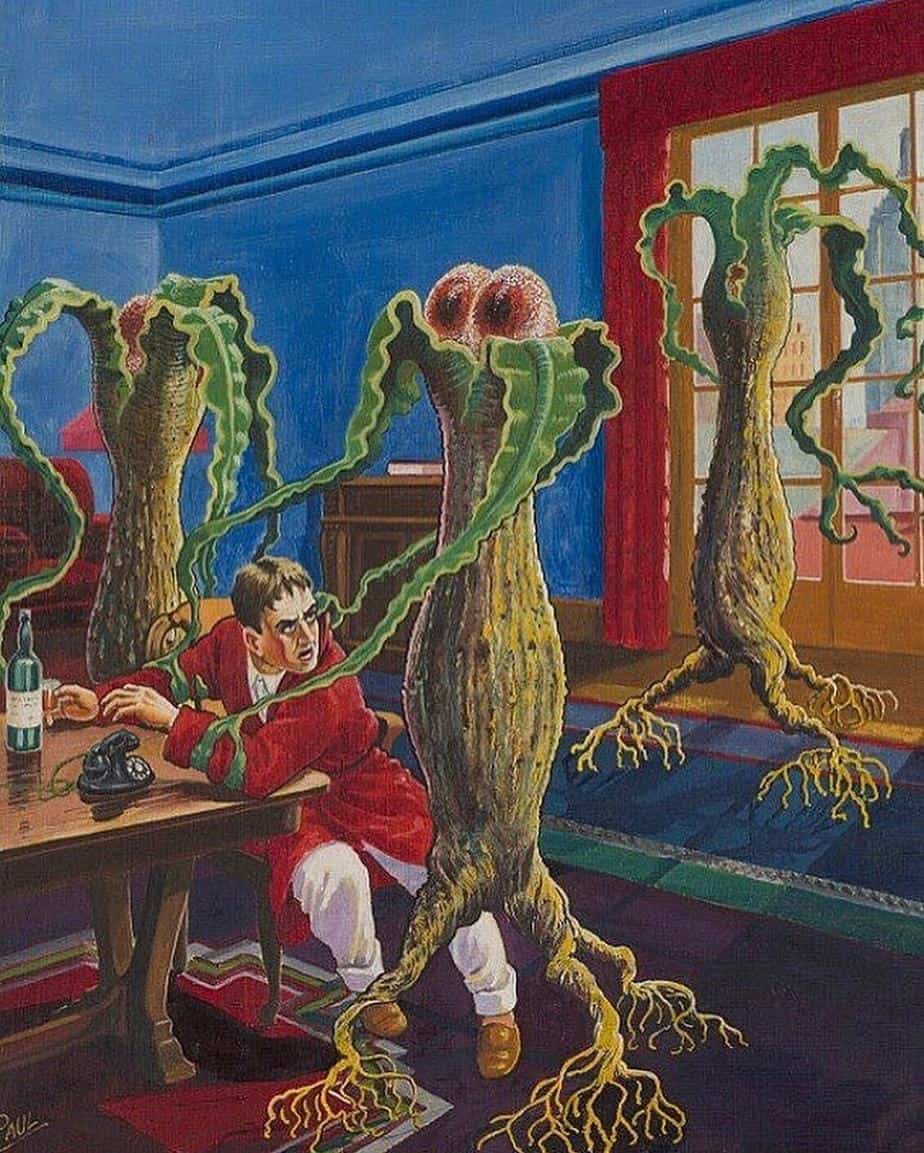

Long before Day of the Triffids, carnivorous plants existed in Gothic horror, including in vampire stories.

This subgenre was pioneered by Phil Robinson who wrote “The Man Eating Tree” (1881).

In “The Story of the Grey House” guests stay at a secluded country mansion but are strangled and drained of blood by a demoniacal creeper growing among the shrubbery.

Another is “The Purple Terror” (1899) by Fred M. White.

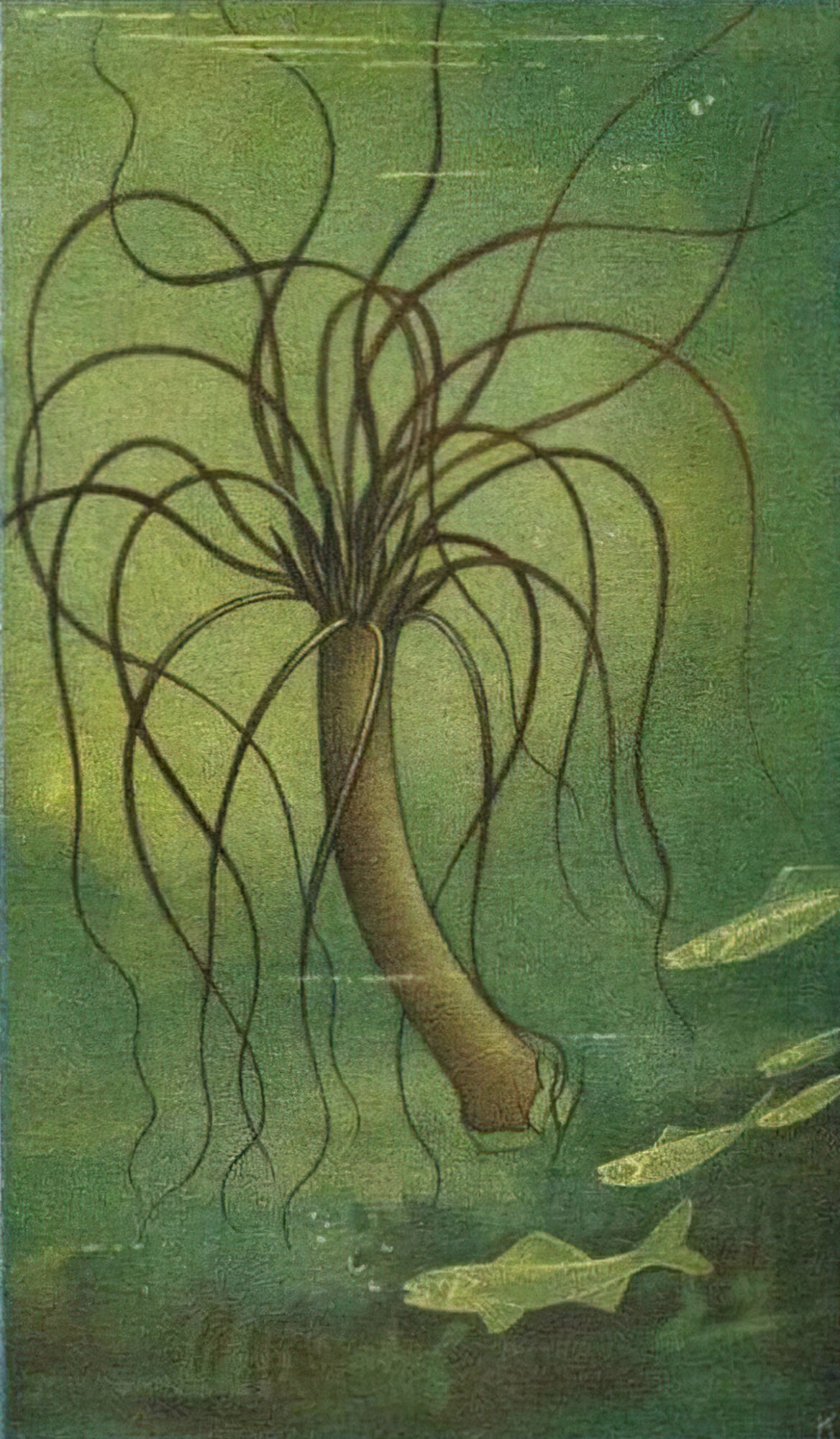

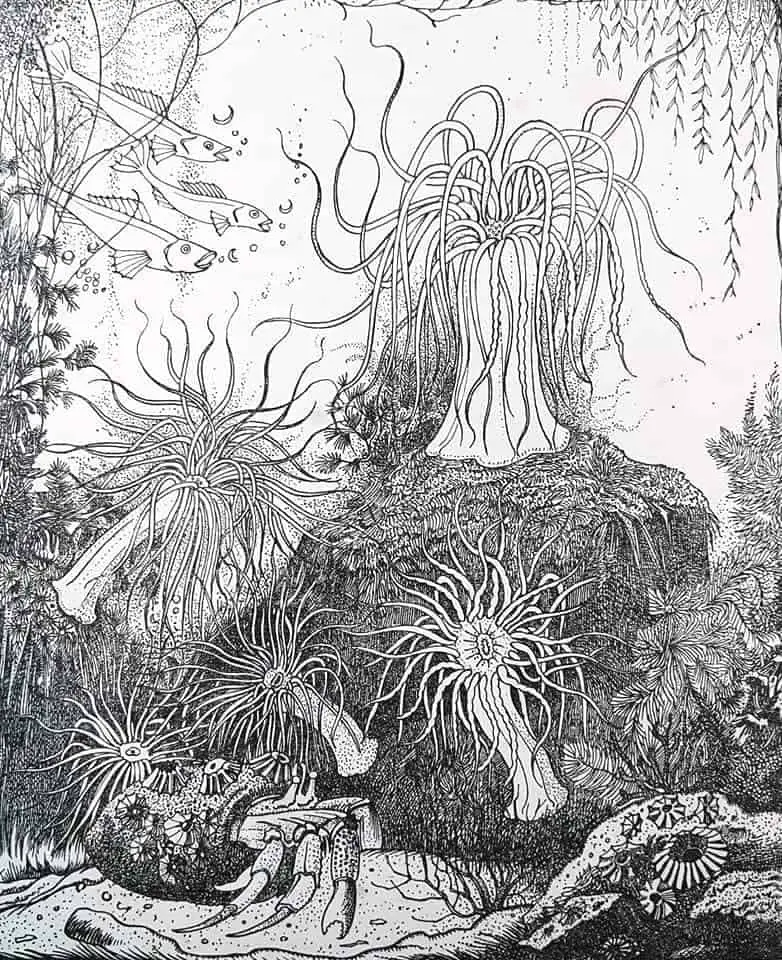

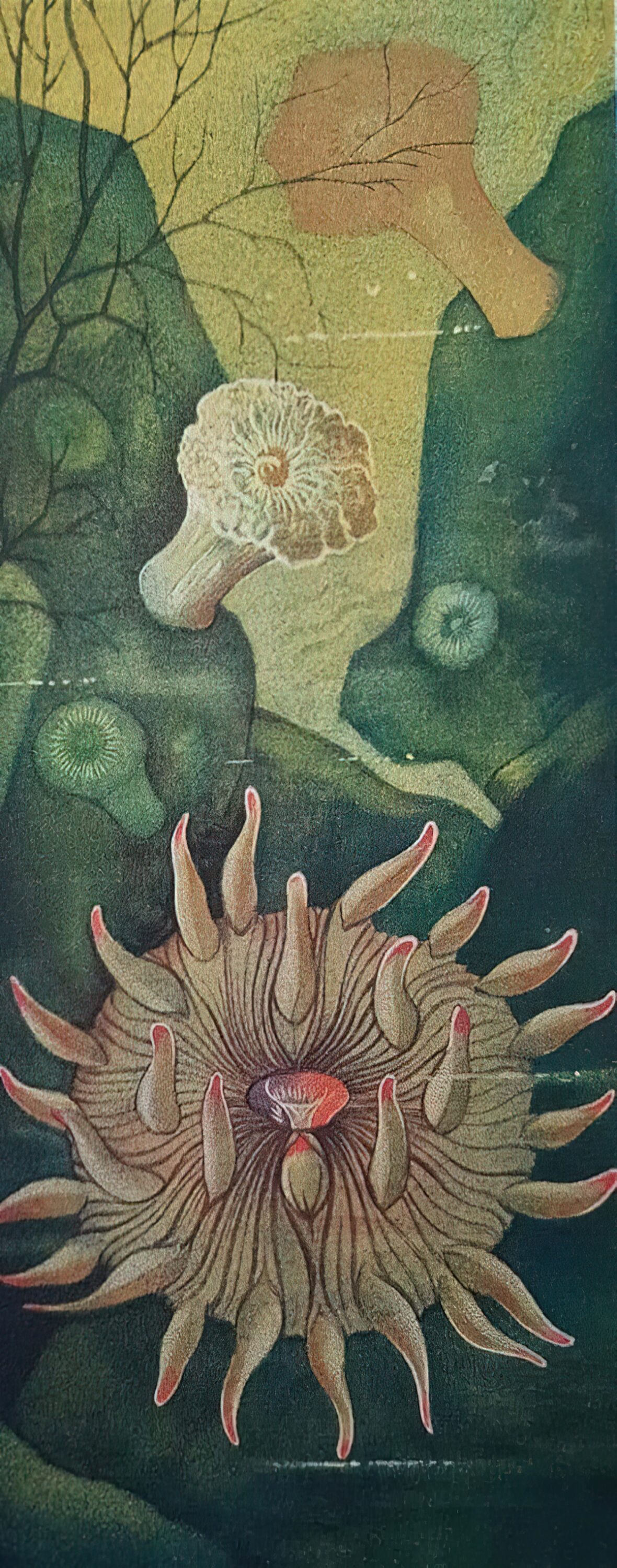

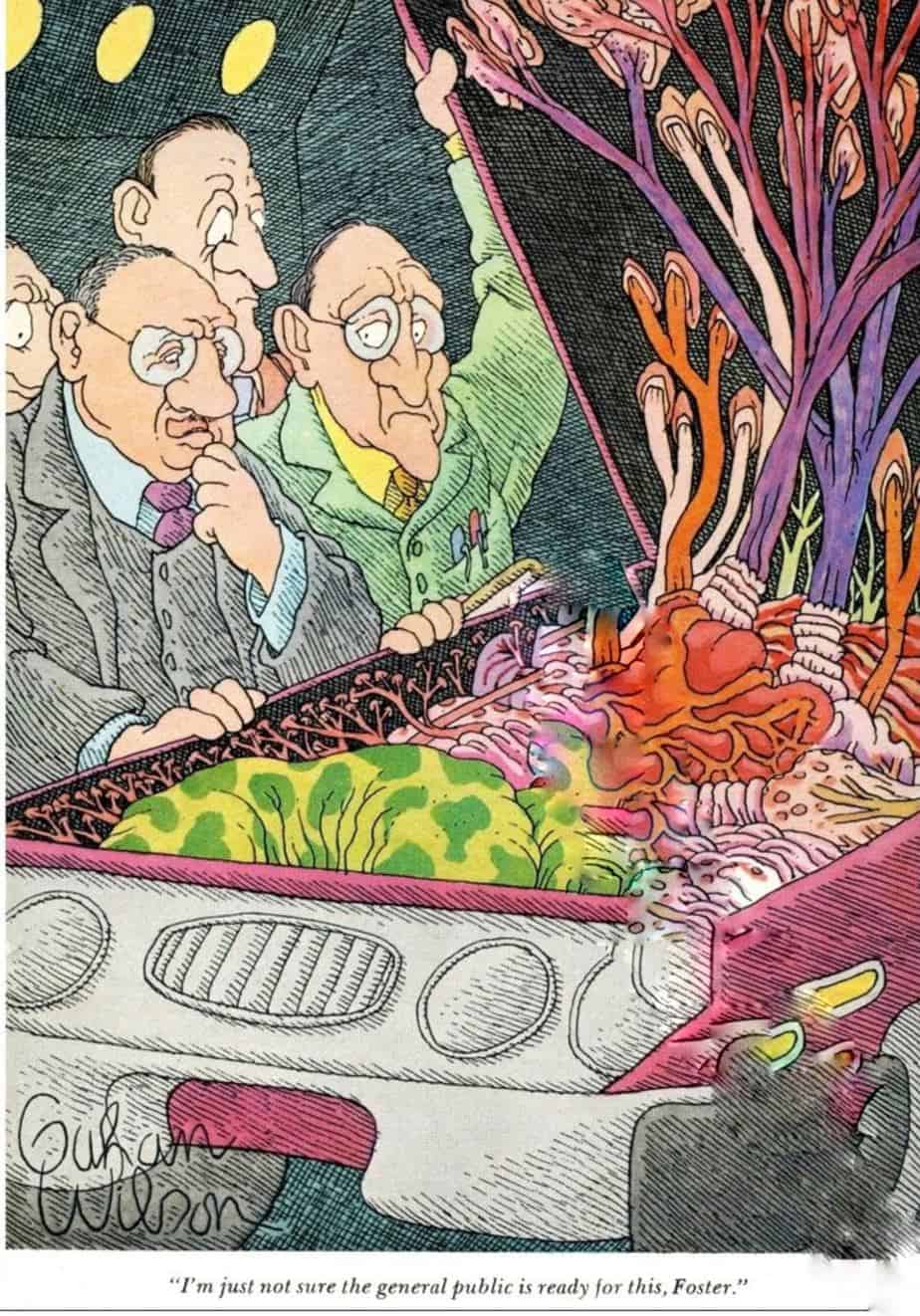

AQUARIUM MANIA

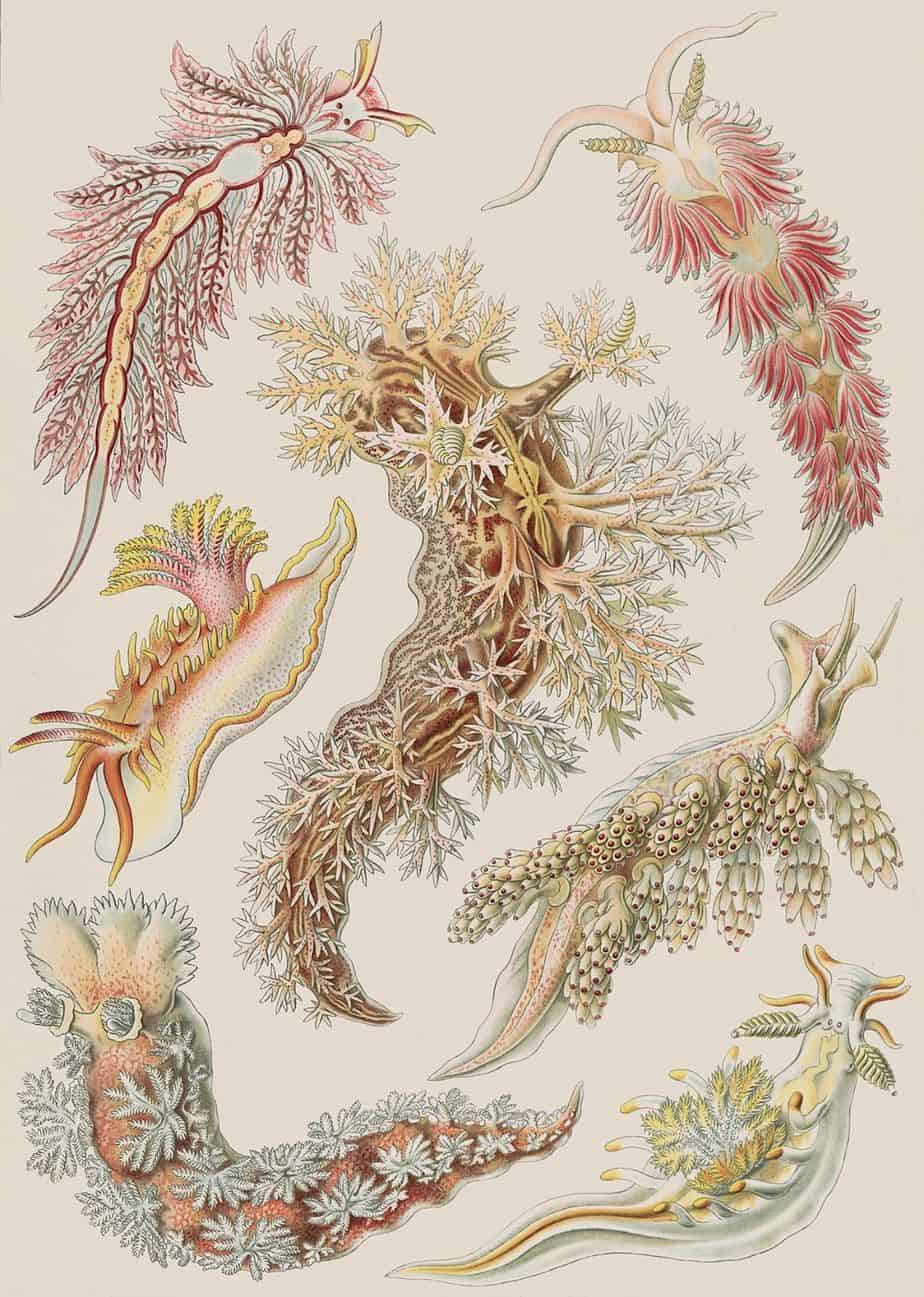

The Public Domain Review has a great article about the golden age of aquariums.

Walking Trees

Meal One by Ivor Cutler

Ferns Work Together In Bee-Like (Eusocial) Colonies

Fruits and Vegetables Are Trying to Kill You: Antioxidant vitamins don’t stress us like plants do—and don’t have their beneficial effect from Nautilus

“Professor Jonkin’s Cannibal Plant“, a short story in the public domain

Trees In Japanese Folklore from Curious Ordinary

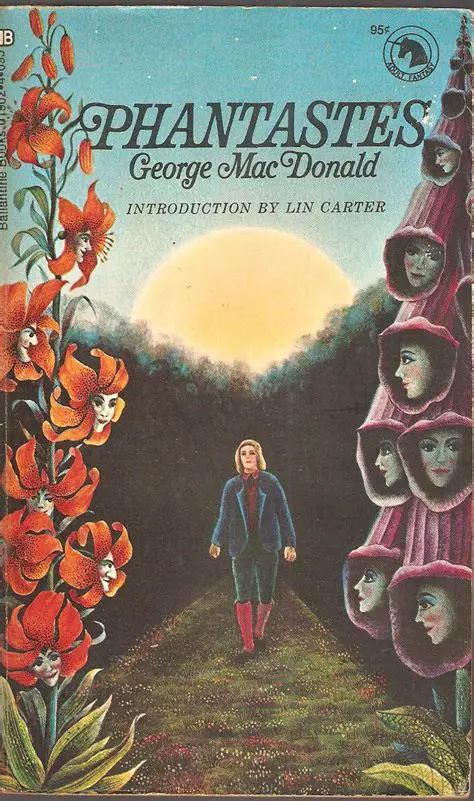

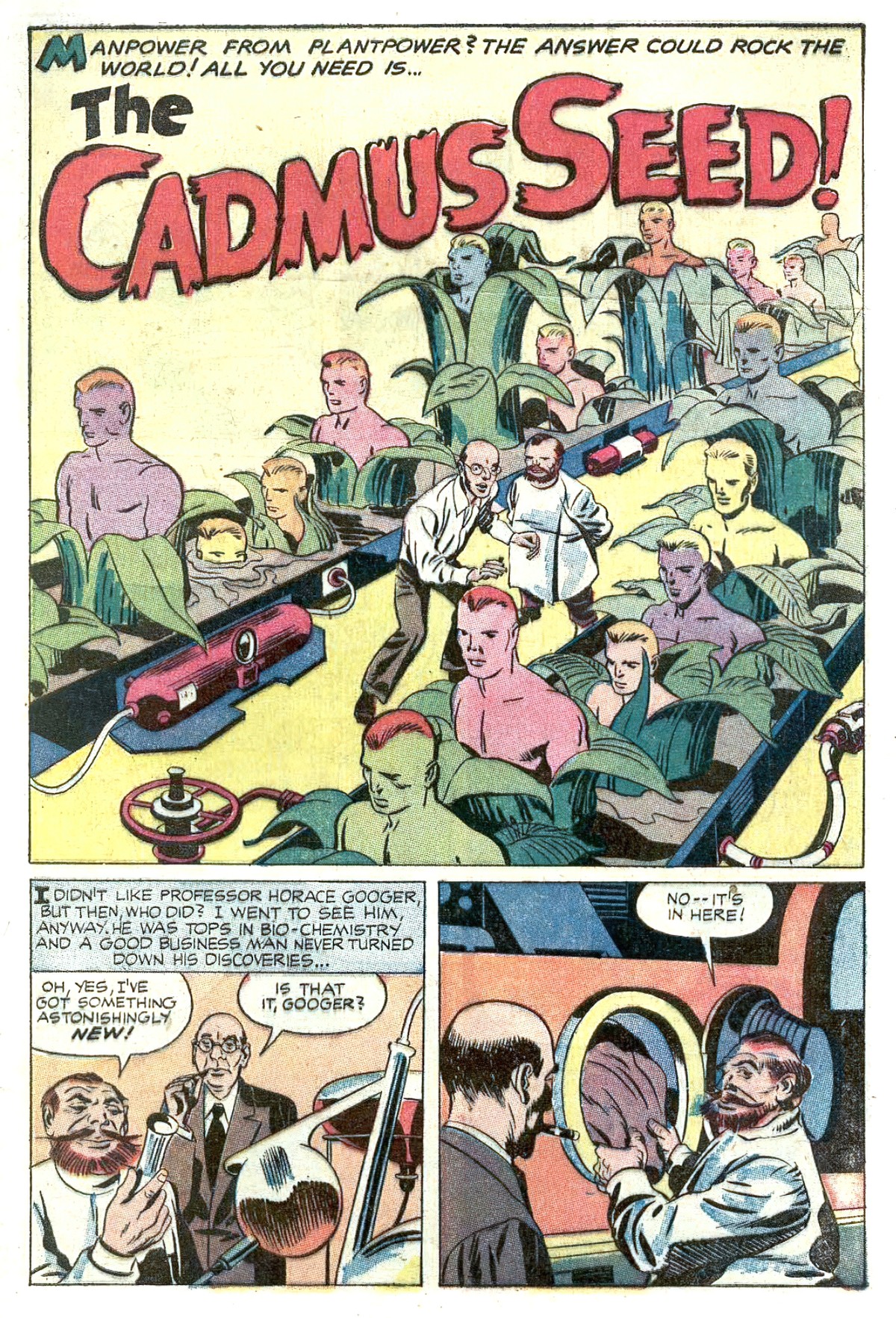

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF EVIL ROOTS: KILLER TALES OF THE BOTANICAL GOTHIC Rappacini's Daughter by Nathaniel Hawthorne The American's Tale by Arthur Conan Doyle Carnivorine by Lucy H. Hooper The Giant Wisteria by Charlotte Perkins Gilman The Flowering of the Strange Orchid by H.G. Wells The Guardian of Mystery Island by Edmond Nolcini The Ash Tree by M.R. James A Vine on a House by Ambrose Bierce Professor Jonkin's Cannibal Plant by Howard R. Garis The Voice In The Night by William Hope Hodgson The Pavillion by Edith Nesbitt The Green Death by H.C. McNeile The Women of the Wood by Abraham Merritt The Moaning Lily by Emma Vane

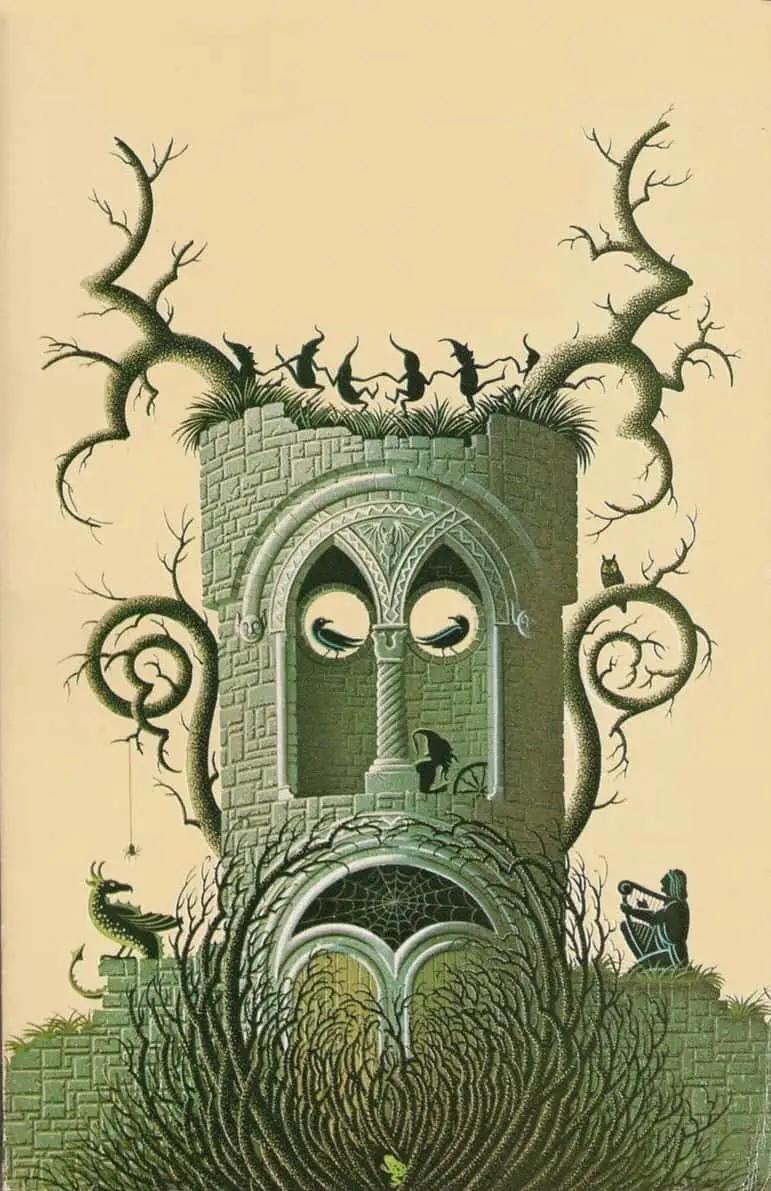

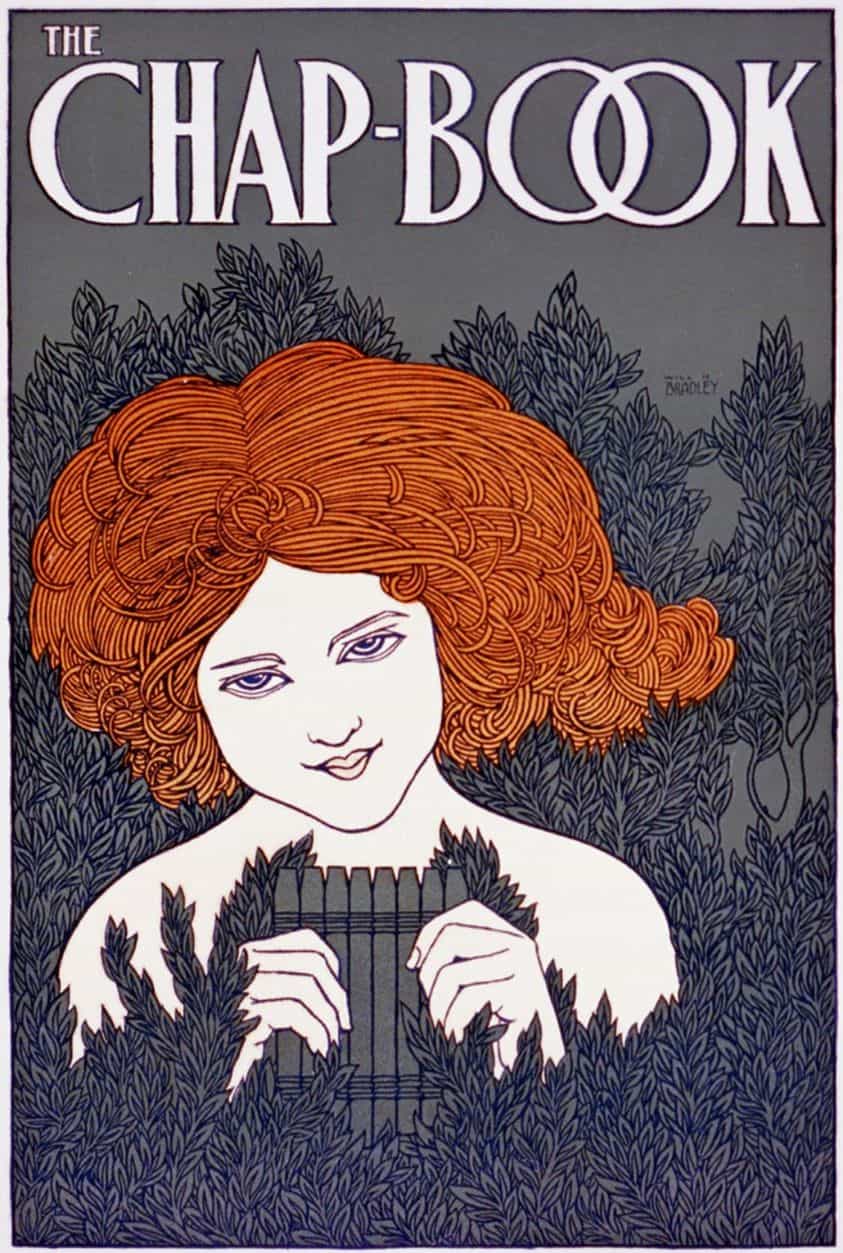

Header illustration: The cover of DER ORCHIDEENGARTEN, considered the first German fantasy magazine.