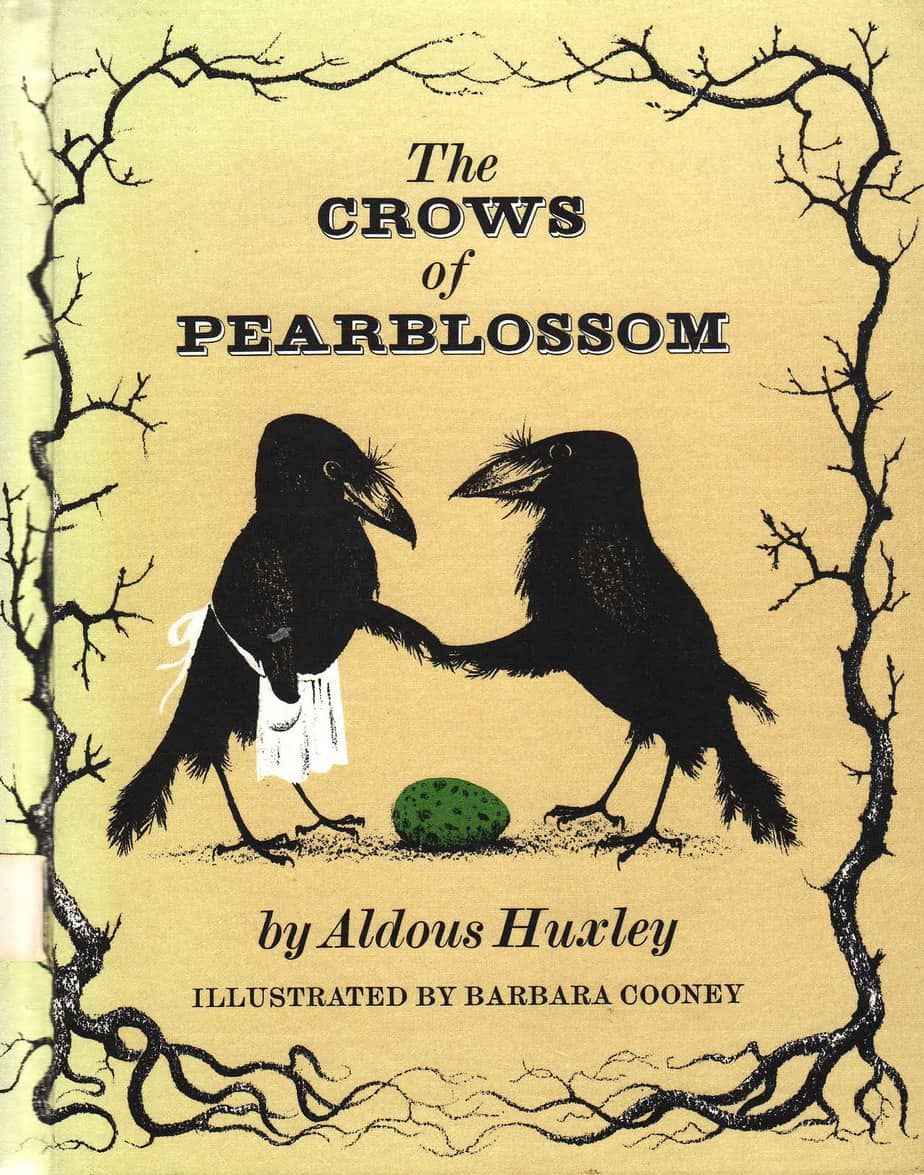

The Crows of Pearblossom is a 1967 picture book written by Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) and first illustrated by Barbara Cooney (1917-2000). This story was published after Huxley’s death. He originally wrote it in 1944 for the specific audience of his niece.

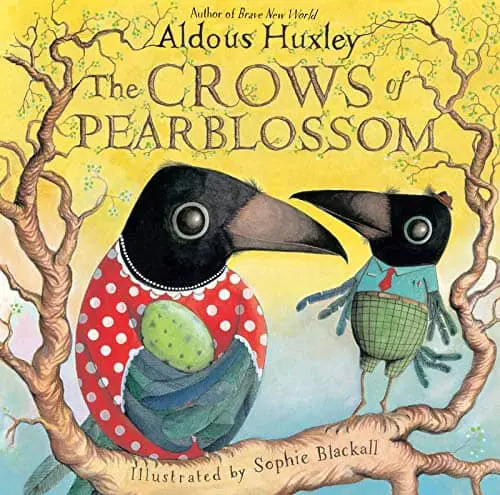

The Crows of Pearblossom was much more recently re-illustrated by contemporary children’s illustrator Sophie Blackall, so has obviously found its audience. But I first encountered this story described as ‘ an odd little book for children’. I’m always interested in ‘odd little books’ because aren’t all books for children inherently odd? They’re wacky, they’re carnivalesque, they contain unique, resonant imagery, and the best of them see the world through the eyes of a three-year-old. And three year olds live on a different planet. So what makes some children’s books feel ‘odd’ while others feel…. ‘expected’?

Being ‘an odd little book’, I expected something like Meal One by Ivor Cutler, which is truly wacko in a wonderful way, but in fact Huxley’s story reminds me of little known Australian picture book The Cider Duck by Joan Woodberry because the climax involves animal cruelty of the sort that I wouldn’t expect today. Especially in Australia, perhaps, cruelty to a snake is a big no-no. If we find a snake in our yard we are required to call animal protection, who then remove the snake. Snakes are not killed.

I find The Crows of Pearblossom uncomfortable for another reason entirely, and that’s the display of misogyny. Did Huxley realise it was there? 1944 was an overtly misogynistic era. Perhaps someone more familiar with Huxley can answer that one.

Huxley aside, my personal reaction leads to another interesting question: In order to critique an idea the storyteller must first show it. I’m clear on that. But in stories for children, to what extent must we critique a bad bit of culture? We no longer accept overtly didactic stories for children, and modern efforts which teach lessons are considered old fashioned.

However, this old-fashioned form of didacticism may have been replaced with what is simply an updated version: The expectation that any sexism/racism/ableism and so on is remedied or somehow addressed by the end of the story, partly as a way to signal to the audience that, no, the storyteller is not themselves sexist/racist/ableist. Most gatekeepers of children’s literature seem to accept that children are not tabula rasa in the sense that they will ape the bad behaviour of the Horrible Henrys of children’s literature, but do remain uncomfortable with children’s book which are as sexist, racist and ableist as the real world.

I happen to be in that camp myself, by the way. This is because anything ending in -ism is ‘the water we swim in’. Unless stories point it out somehow, -isms will continue to thrive in the worst possible way — invisibly.

SETTING OF THE CROWS OF PEARBLOSSOM

- PERIOD — This story could take place anywhere, anytime, but The Crows of Pearblossom could only have been written in an era prior to collective consciousness about animal cruelty and protection.

- DURATION — This is unclear, though we can assume the main action takes place over a week or so. The story calls back to a long-running pattern of a snake consistently, routinely, stealing a bird’s eggs.

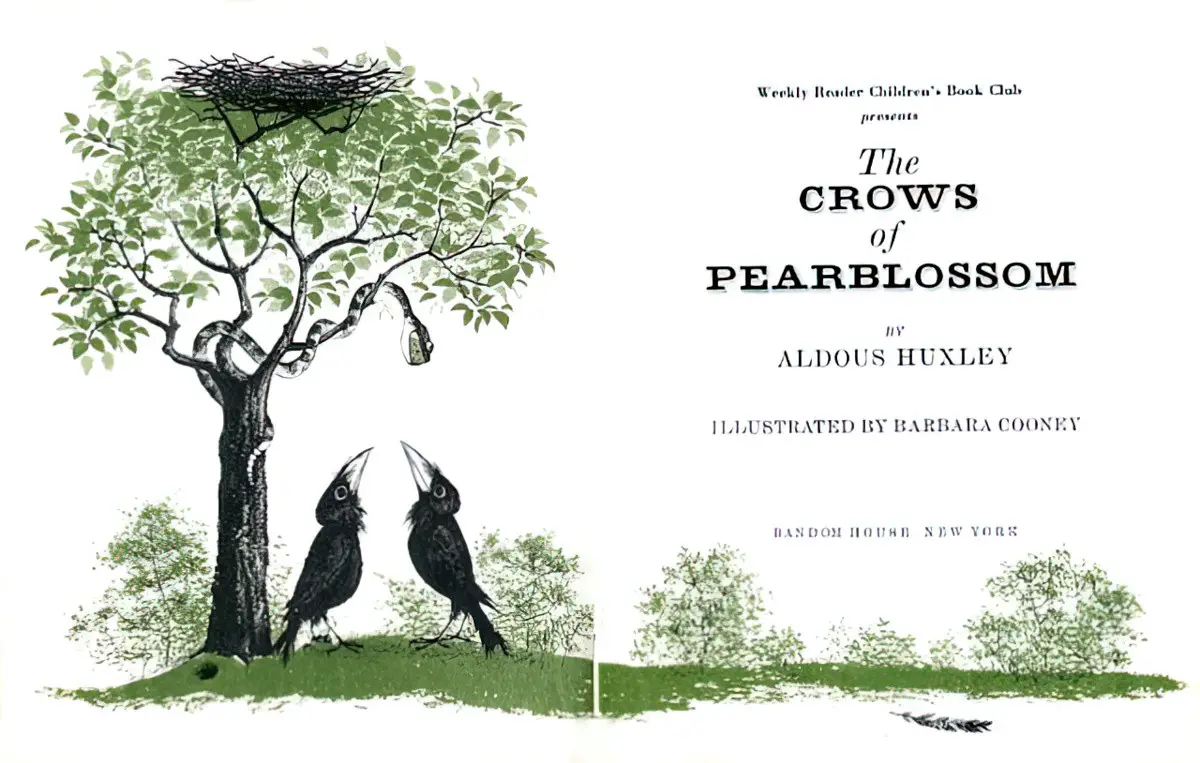

- LOCATION — In a tree, we might guess a pear tree from the title, but it’s actually a cottonwood tree. ‘Pearblossom’ sounds like something out of Foxwood tales, an anthropomorphised animal utopia, but if that’s your expectation going in, prepare to be a little taken aback.

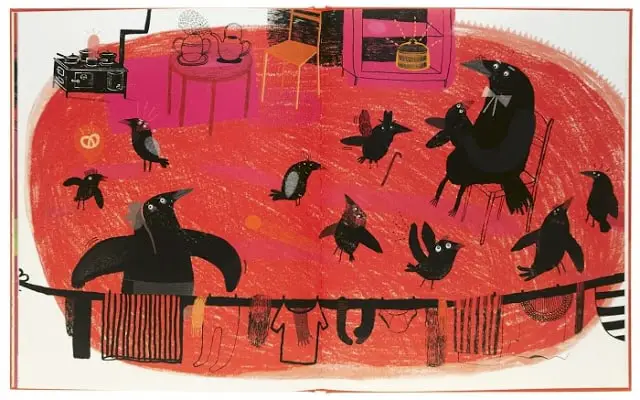

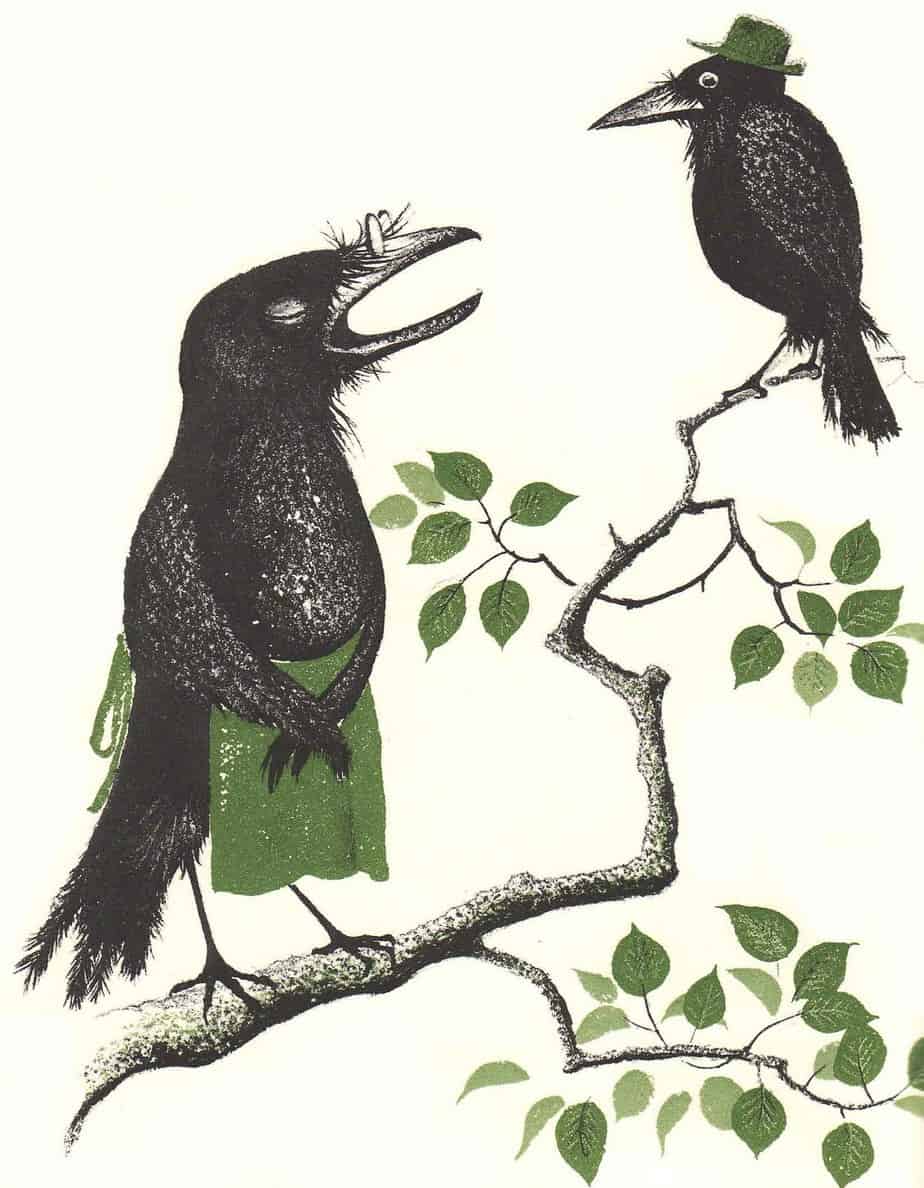

- ARENA — Cooney’s illustrations are spot illustrations only, which is unusual for Cooney, whose later full spreads are gorgeous. (See Miss Rumphius, for instance.) Even when the crow and the owl visit a house, we see only the top of a chimney. The effect of this is interesting: There’s no sense of an ‘arena’, but rather a sense of connected spaces which we cannot (and need not) place spatially in our heads.

- MANMADE SPACES — Chimneys in children’s stories are starting to really fascinate me for how they are used metonymically to stand for human habitation. We see only a chimney, not a full house.

- NATURAL SETTINGS — Likewise, in Cooney’s version, we see only a branch of the cottonwood tree, not the full tree. This is an interesting choice because after reading a bit about birds, this is very much not how birds see the world. (I also know from my daily walks that birds, well, magpies, see everything. In this country they swoop you.) I can believe that insects see their world in macro, but evidence suggests birds have a far better grasp of an overall landscape than humans do, and better eyesight, too.

- WEATHER — The environment of this story is devoid of weather events. This is in line with your typical utopia, in which weather is sometimes exciting but never calamitous.

- TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY — There may or may not be some technology which your plot will rely on. In some genres (especially science fiction) this technology will be central.

- LEVEL OF CONFLICT — We don’t know what’s going on in the wider world of the story. The conflict is entirely between characters, one of whom is more clearly animal (the snake is snakey), the other is more anthropmorphised (the birds is unfortunately human enough for her offspring to require nappies).

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE CROWS OF PEARBLOSSOM

PARATEXT

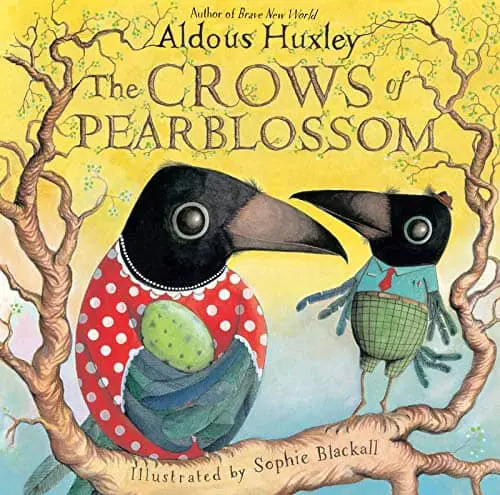

I doubt this picture book would have found longevity (or publication) without the platform of the author as a writer for adults, so the later version of this story reminds adult buyers on the front cover that this is by the author of Brave New World.

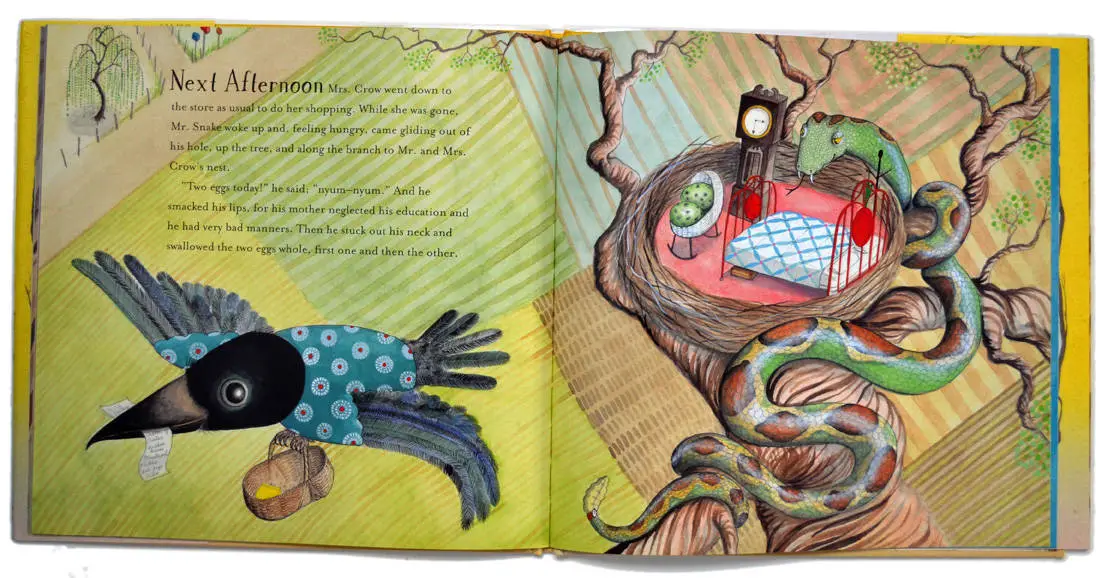

Written in 1944 by Aldous Huxley as a Christmas gift for his niece, The Crows of Pearblossom tells the story of Mr. and Mrs. Crow, who live in a cottonwood tree. The hungry Rattlesnake that lives at the bottom of the tree has a nasty habit of stealing Mrs. Crow’s eggs before they can hatch, so Mr. Crow and his wise friend, Old Man Owl, devise a sneaky plan to trick him.

This funny story of cleverness triumphing over greed, similar in tone and wit to the work of A. A. Milne, shows a new side of a great writer.

marketing copy

I disagree that this work is similar to that of A.A. Milne, whose 100 Acre Wood is a genuine utopia, where no one is gendered, despite the reflexive male coding of everyone. The similarity is the existence of the sage owl. That’s about it.

SHORTCOMING

Who is the main character in this story? There isn’t one — it’s the story of a small group of animals.

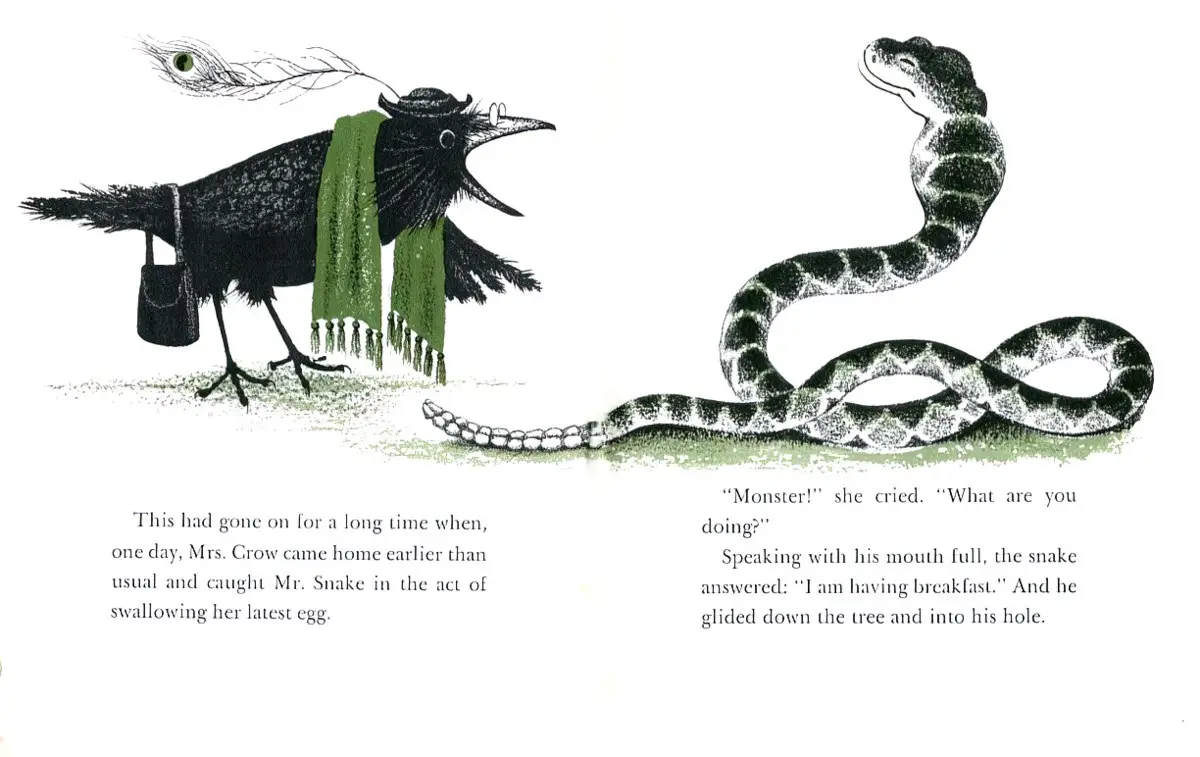

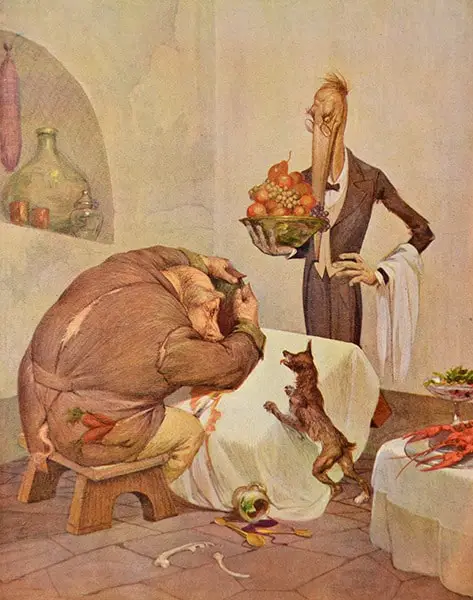

The female crow is initially presented as the clear victim, though the peacock feather stuck in her modest hat suggests she has big ideas above her station. (A Hyacinth Bouquet archetype.) Every day she goes out to do the shopping, and when she returns her precious fertilised egg has been eaten by the snake.

But despite being the victim of serial… and I do mean serial… infanticide, the shortcomings of Mrs Crow are substantial. This is reflected in both the text and the illustrations. You’ll be familiar with this bossy housewife trope from other stories. To take another example, Larry McMurtry uses her to comical effect in Lonesome Dove, with the character of Peach.

Here she is, introduced in full comedic form:

Peach at least wrings a rooster’s neck her own self. A more annoying version of the same archetype is Sybil of Fawlty Towers. In the very first scene, Sybil ‘nags’ her husband. She’s asking the impossible: She’s asking him to carry out a maintenance task, and every time he starts, she requires him to do something with the menus. This poor, hapless husband can’t win.

Lonesome Dove and The Crows of Pearblossom are different genres for different audiences, but the trope is identical: A white woman exacts retributive justice via the male characters in her life, and she persuades them to do this with veiled insults about him being insufficiently manly if he does not do her bidding. In contemporary lingo, this MO is an inherent part of the ‘Karen’: powerful tool of the patriarchy. The difference between a man exacting vengeance and a woman persuading a man to exact vengeance is clear: The audience is always, always more sympathetic to the person who at least has ‘the balls’ to go in and do the hard work himself. Audiences rarely sympathise en masse with the Peaches and the Mrs Crows of narrative.

There is also some body size issues going on with this one, with fat women coded as bossy wives, and I can’t even be bothered with that. I’m so tired of it.

Recall, too, the violent reactions directed at Anna Gunn, who played Skyler White in Breaking Bad. It’s all part and parcel.

the reason men are always surprised when their unhappy wives leave them is because they’ve been brought up to EXPECT her to be unhappy. Now I can’t stop seeing the ‘unhappy wife’ trope everywhere.

Sofie Hagen on Twitter 7:32 PM · Jul 29, 2021

DESIRE

Here is Mrs Crow of Pearblossom, mouth open, eyes shut. The visuals are clear: She wants her husband to kill the snake. She is all talk, but blind to the fact that she’s asking a lot of the (smaller) male crow. By this point in the story, any sympathy for her has evaporated, by design.

Yet the rules of masculinity are so strong, that these male characters always seem to do her bidding. Audiences, conservative in consumption, are not expected to question this part.

OPPONENT

The snake is typically snakelike. If you’ve ever kept poultry in Australia you’ll know that the snake’s MO is to sniff out a coop and camp out nearby, enjoying eggs daily. The chickens and their eggs belong to the snake now, until you get rid of the snake (or the goanna).

Sympathy transfers away from the female crow to the male crow, who looks appropriately terrified at the prospect of killing the Minotaur of this story — the snake.

PLAN

Audiences also empathise with tricksters rather than with heroes who go straight in to battle without a clever plan.

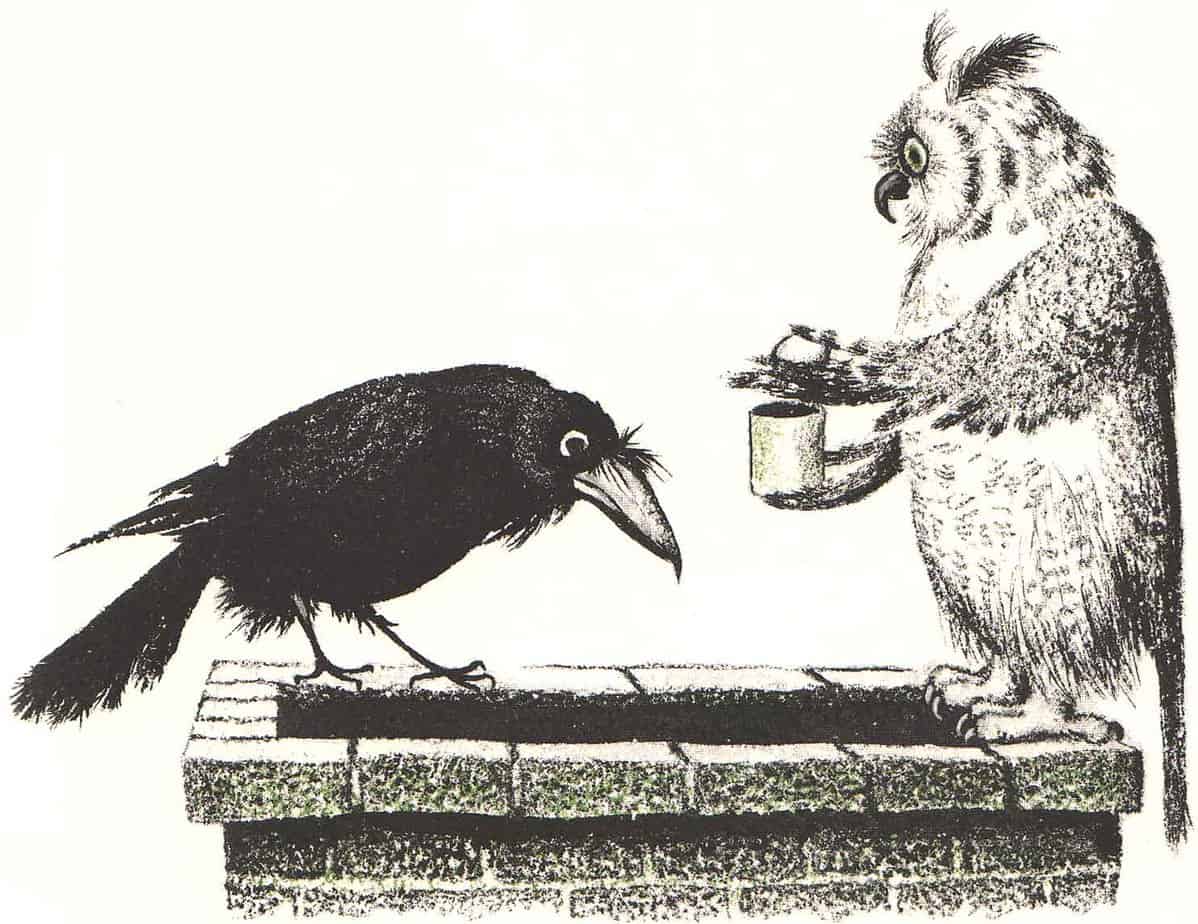

In traditional mythic fashion, the male crow of Pearblossom finds a fairytale mentor, in the form of an owl. Twentieth century children’s stories frequently utilised owls as the sage archetype. (A.A. Milne spoofed the trope.) Sure enough, the owl has an idea, but this plan will work. The owl and the husband crow will trick the snake by making fake eggs (basically the poisoning trick) and painting them to look exactly like Mrs Crow’s eggs.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

This part of the narrative is disturbing to me. Although the snake is the baddie in this story, it is decidedly uncomfortable to watch any animal writhe in pain after eating something poisonous.

The snake wraps himself in a knot around the branch and dies. I’m confident that ‘wrapping himself in a knot’ was coded 70-80 years ago as ‘just desserts’. Even today, children’s writers prefer to avoid direct retributive justice by implicating the villain in their own demise. One Goodreads reviewer calls this ‘deliciously dark’. Indeed, Edward Gorey pulls off similar. However, I just find it dark.

Secondarily, there is also interpersonal issues between the husband and wife crow. In one spread, the homosocial bond between the crow and owl (both coded male) is emphasised when they confront Mrs Crow by telling her, “You talk too much.” Oof.

The problem, of course, is not that she talks too much. It’s that she’s all talk, and that women who use the patriarchy indirectly for retribution are as bad as men who use it directly. This is the aspect that isn’t fully explored on the page. The sociopolitical implications of that one-sided remark really sting with a 2020 reading.

ANAGNORISIS

The Minotaur (snake) was a flat baddie and was never going to learn anything. He ends up dead. strung between two branches.

What does a reader take away? Rather than bash something on the head quickly and put it out of its misery, poison it? Slowly? So that it appears to die through its own greed? This is the children’s book version of Se7en (1995), utilising one of the Seven Deadly Sins.

NEW SITUATION

Like Peach of Lonesome Dove, who wrings a rooster’s neck no probs, Mrs Crow is sufficiently callous to use the dead snake carcass as a washing line for her babies’ nappies.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

Mr and Mrs Crow have many, many babies and anyone who knows anything about environmental equilibrium will realise that the ecosystem is a delicate thing. There is such a thing as too many crows and not enough snakes.

What has happened to Mr Crow? We don’t see him with Mrs Crow at the end. She must have had her egg babies fertilised somehow, but there may be a homosexual subplot. I’m wary of reading too much into stories of this age, but on the other hand, in an era when homosexuality was illegal, dangerous and therefore taboo, ‘veiled’ stories about gay lives had to be heavily veiled.

An excellent example of that is “The Lumber-Room” by Saki, a story which I didn’t even realise was a queer story until someone else pointed it out to me (and then it was obvious).

An excellent counter example is my contemporary interpretation of Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes, which I see as clearly, unequivocally gay. But from what we know of Potter’s life and times, there’s absolutely no reason to think she wrote it with queer intent.

RESONANCE

I believe The Crows of Pearblossom is an excellent example of a children’s book in which the author’s celebrity leads directly to its reprinting. I despise this story, and I doubt a newcomer to children’s publishing would have found a place for their similar but contemporary manuscript.

Did Huxley write this ‘for children’ (in general)? Nope, and this is the issue. He wrote it for a specific child. I also suspect he wrote it for her adult co-readers equally, with winks to the adults about martinis, obvious lampshading of why there just happens to be paint lying around, and so on. We’ll never know how many in-jokes and real-life animalification Huxley included in this story for his niece. The wider readership is left only with what’s on the page.