We know when something is creepy. But how to define it?

On The Nature of Creepiness is a study by McAndrew and Koehnke, who realised there had never been an empirical study on what humans find creepy. The results were ‘consistent with the hypothesis that being “creeped out” is an evolved adaptive emotional response to ambiguity about the presence of threat that enables us to maintain vigilance during times of uncertainty’.

Being ‘creeped out’ is sometimes associated with the physiological reaction of feeling ‘cold or chilly’, which makes me think of ghost lore. According to many folk beliefs, ghosts bring coldness with them. But the sensation of feeling chilly also happens when we feel socially excluded, so feeling that coldness is part of a more generalised defence mechanism.

THE CREEPIEST OCCUPATIONS

Four occupations were considered far creepier than others:

- Clowns ― see this post for why, exactly, we probably find clowns creepy (it’s the smile and the mask)

- Taxidermists ― because of their proximity to death, and their apparent fascination with it

- Sex shop owners ― their apparent fascination and proximity to sex

- Funeral directors ― because of their proximity to death, making them the embodiment of The Grim Reaper (Where there is death, there are funeral directors, after all.)

Many storytellers have been utilising the creepiness of these jobs in their narrative, sometimes subverting audience expectations by humanising people with creepy jobs, other times using them straight outta the box.

Pictured above

- The clown from Stephen King’s IT (one of many creepy clowns across storytelling).

- Angela from Six Feet Under, who has every creepiness factor except being male

- Arthur from Six Feet Under, whose ambiguous sexual orientation becomes fodder for speculation in one episode in particular, resulting in Arthur being falsely accused of sending faeces to the Fishers.

- Barry from Dinner For Schmucks:

Barry ― who seems to lack an internal filter, and who spends his off hours building lovingly detailed dioramas featuring taxidermied rodents ― inadvertently turns the tables on the assembled guests.

Both Roach and Carell joined Fresh Air‘s Dave Davies for a discussion about the film, loosely adapted from the 1998 French comedy Le Diner de Cons. In that film, the idiot character creates elaborate designs out of matchsticks; Roach says he made a conscious decision to change Carell’s obsession to express who he is a bit more.

“There’s a little hint of something sad underneath, and the [stuffed] mice become a way for him to express this optimistic view of life,” he says. “And that’s what made it seem like a kind of creepy-funny thing at first, and then these layers unfold.”

Dinner for Schmucks, NPR

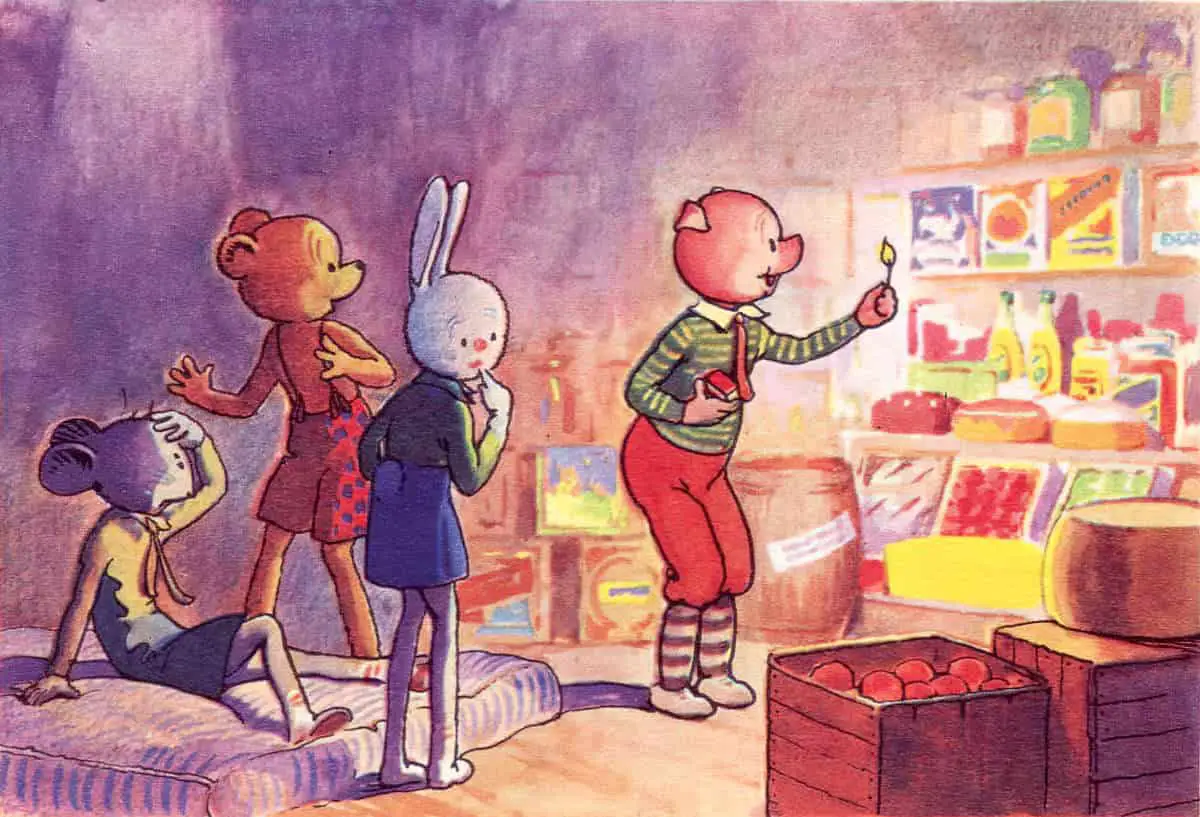

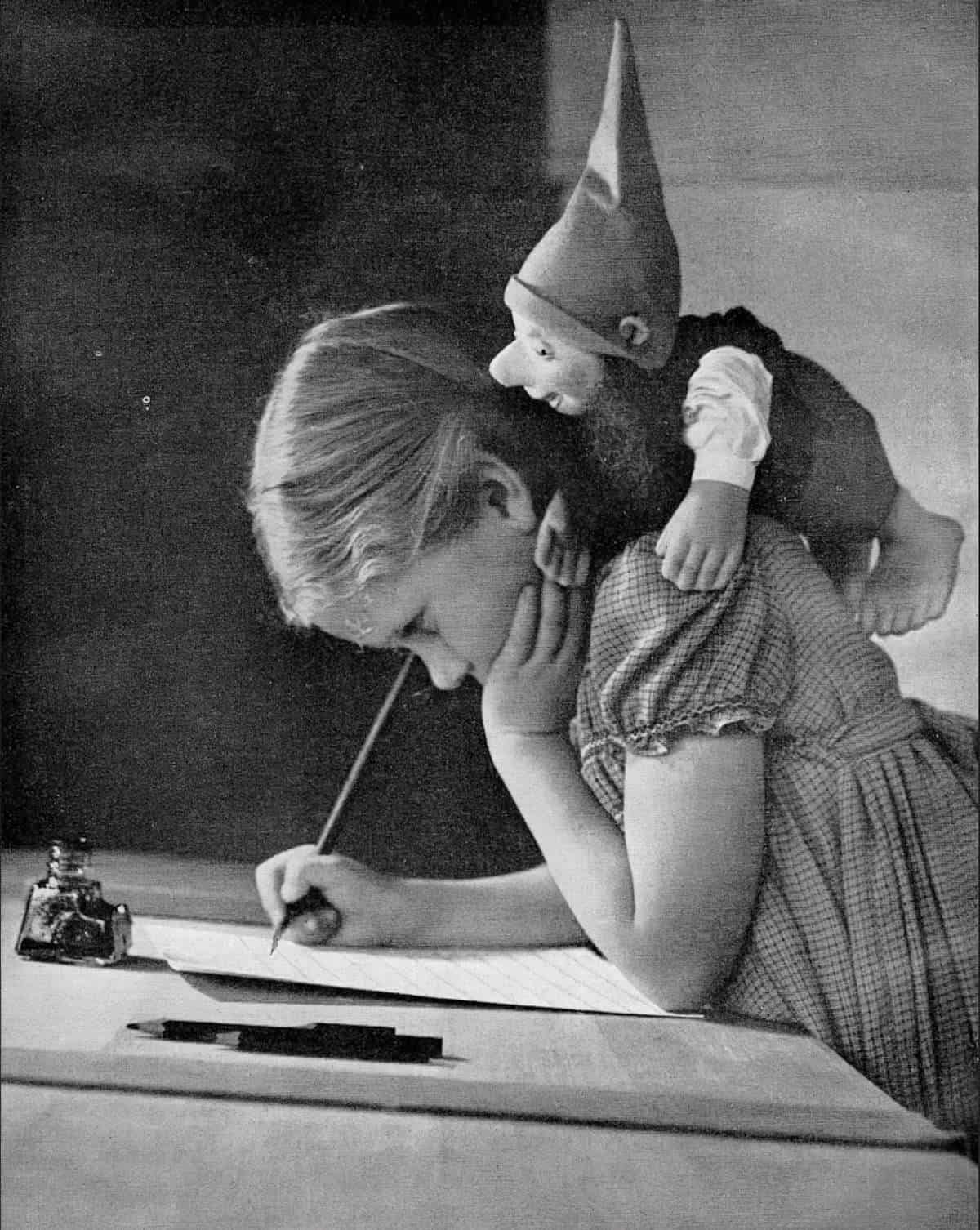

CREEPINESS IN CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Storytellers and illustrators of children’s books can make deliberate use of the creepiness factor to create a frisson of suspense or joyful terror in young readers.

Below is the artwork of an illustrator whose work I grew up with. The Grahame Johnstone sisters were very good at creating creepy villains.

They did this by making use of features which have since been listed in the creepiness study above. Which of the following can you see?

- standing too close

- greasy hair

- peculiar smile

- bulging eyes

- long fingers

- unkempt hair

- very pale skin

- bags under their eyes

- dressed oddly

- licked their lips frequently

- dirty clothes

- laughed at unpredictable times

- made it near impossible for someone to leave without being rude

- relentlessly steers conversation toward one topic

The greenness of her skin affords an extra level of creepiness which is available in fantasy but not seen in real life. We can deduce that if green-skinned people existed in real life, we could add that to the list of creepy.

CREEPINESS CHANGES OVER TIME

When you spend a lot of time looking at illustrations from the first and second Golden Ages of children’s literature, you realise that our idea of ‘creepiness’ must have changed.

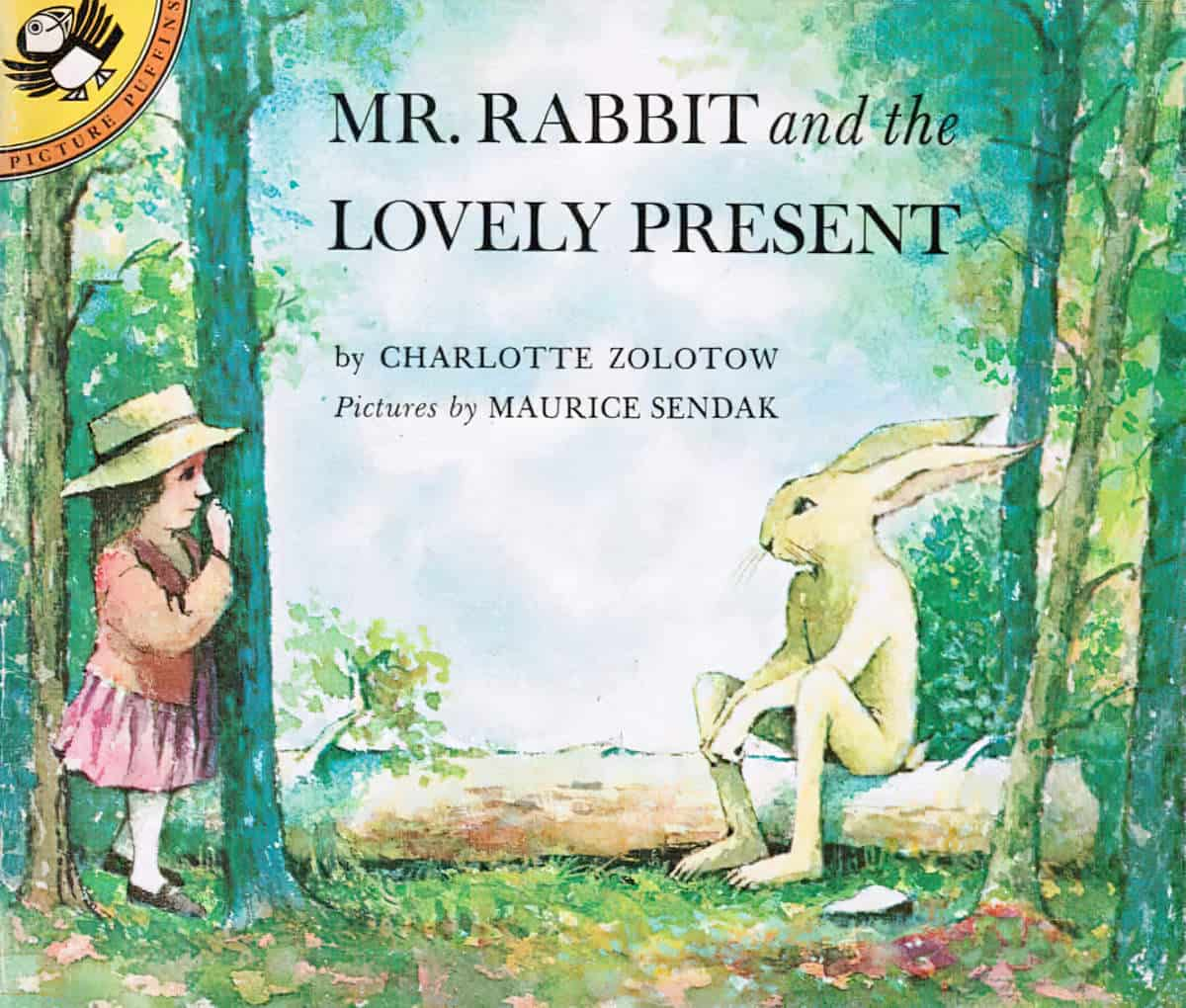

As one example, let’s take a look at Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present, written by Charlotte Zolotow pictures by Maurice Sendak, published in 1962. This is an especially interesting example as it won a Caldecott Honor Medal. This book was fully accepted by audiences at the time.

Now take a look at contemporary consumer reviews of this picture book on Goodreads. The first thing you notice is how many people find the large rabbit creepy.

He’s either imaginary, or been exposed to a radioactive carrot. Either way, I see this kid spending her adolescence in therapy.

CONSUMER REVIEW

Some readers find the rabbit less creepy once they code him as imaginary.

I wanted to like this story but it always felt a little squicky to me. Then I read the intelligent comments of my friend …. And, among other praises and analyses, she pointed out that Mr. Rabbit may be an imaginary friend.

Well that makes so much sense to me now that I actually do feel comfortable loving the story now!

CONSUMER REVIEW

Others had no trouble realising the rabbit is imaginary:

I do really like the aspect of the rabbit being bigger than the girl, making it clear that he is an imaginary helper.

CONSUMER REVIEW

The following reader made a great job of cataloguing exactly why she finds the large rabbit creepy:

I found Mr. Rabbit verging on creepy. Walking on two legs, wearing no clothes, suggesting to the little girl that she buy her mother red underwear, leaning on the little girl presumptuously – violating her personal space – There’s another picture where Mr. Rabbit sits atop a fence and looks at the reader with an expression that seems to say, “Get me out of this picture book.” And in another, he lounges inappropriately on the forest floor, stretched out almost like a courtesan in a nineteenth century painting, his paw touching the little girl’s skirt. It doesn’t help that the contours of his body are those of a middle-aged man growing a beer belly.

CONSUMER REVIEW

- Ambiguity: Is this a man or is it a rabbit?

- (For some readers: Is this a real rabbit or is it imaginary?)

- Standing too close

- Touching

- An age difference

- He is male (therefore statistically more likely to be a sexual predator)

But what did 1960s audiences think of this book? Looking at other examples of 20th century children’s stories, elongated limbs of animal characters (ie. children with human heads) were common. I haven’t seen these proportions on animal characters in contemporary children’s books:

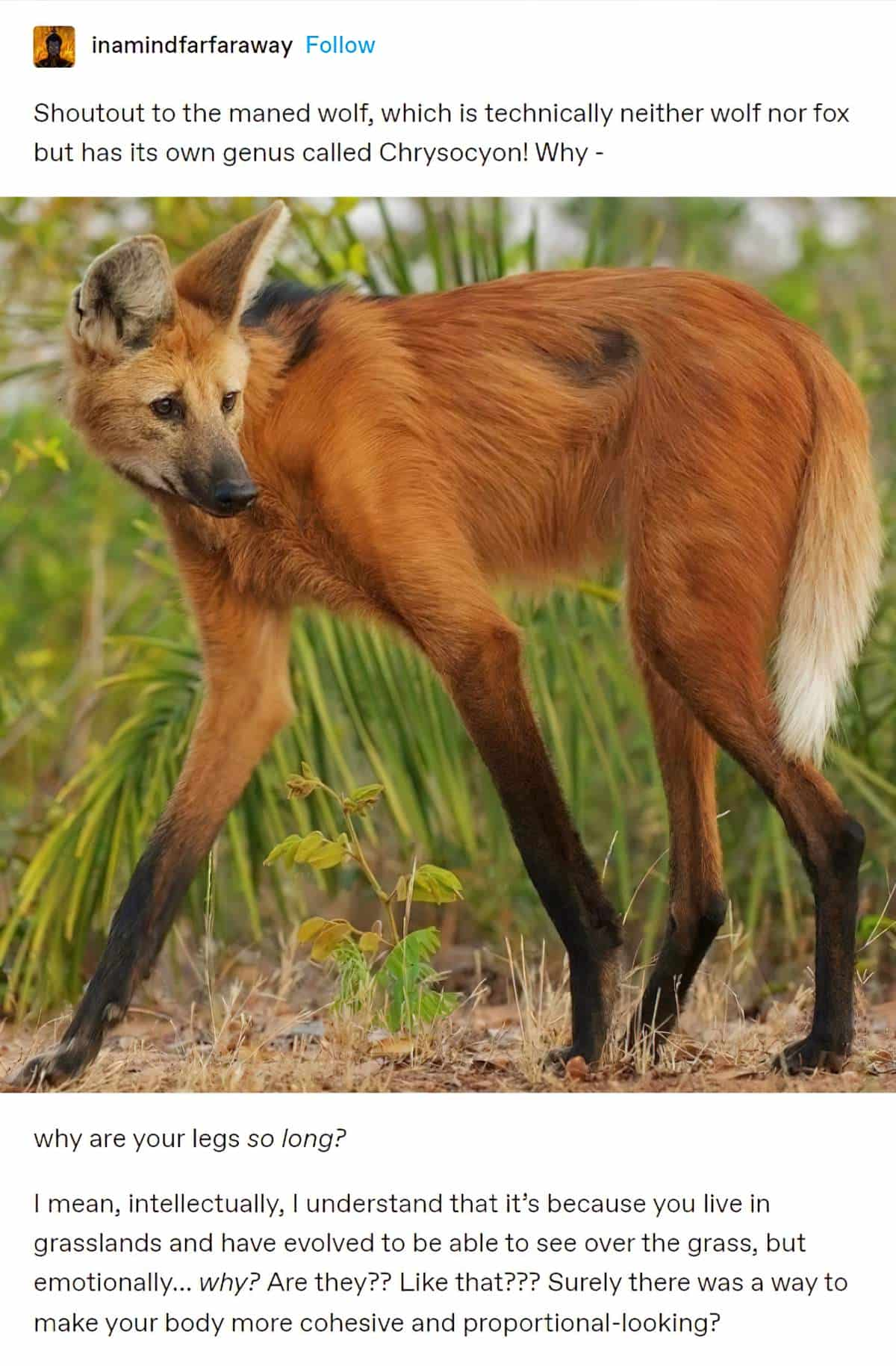

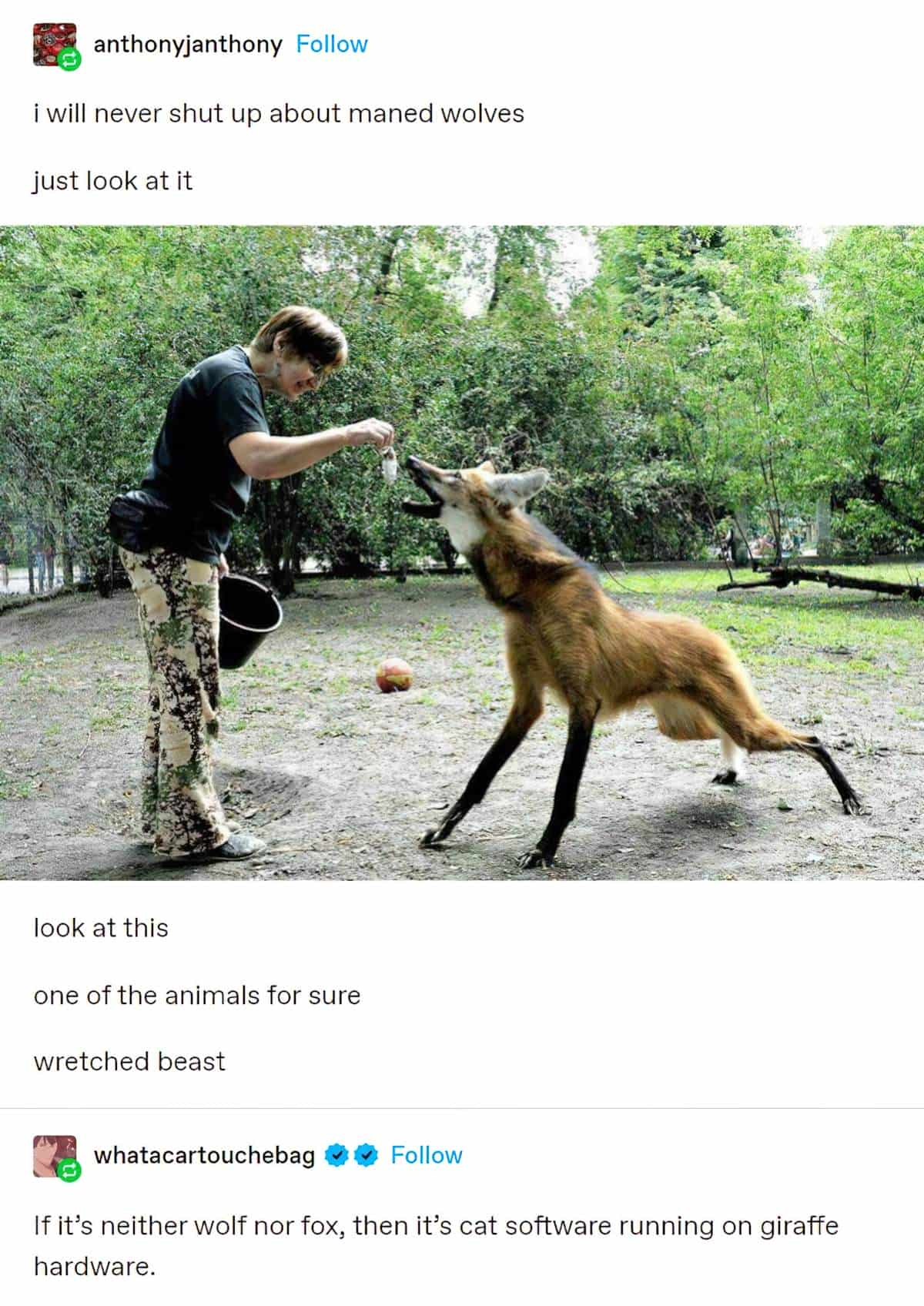

Look, surely those long legs have something to do with it.

There was far less awareness of predatory adult behaviour in the 1960s. We know this. Changes in attitudes, sadly, track directly with men leaving primary teaching positions. By the end of the 1980s, the book buying public had started to think quite differently about stories in which grown men hang out with ‘little girls’. (The word ‘little girl’ is used to refer to the child character in Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present.)

Or perhaps something else is at play. Perhaps readers in the 1960s were less likely to ascribe any gender at all to a fantasy rabbit? If Mr Rabbit is in fact agender, that would remove one of the known creepiness factors. As a corollary, commentators will quite often say that Winnie-the-Pooh is agender.

I don’t entirely buy this. Children, for sure, absorb gender markers such as the word ‘Mr’ when decoding a text or a situation. This has been studied in educational settings, and even applies to so-called ‘universal he’. (Girls don’t think ‘he’ includes girls.)

INTERROGATING OUR OWN CREEPINESS RESPONSE

When we consider the creepiness of ‘standing too close’ I’m reminded of how British people mostly have a much smaller personal distance than Australians and New Zealanders. Yet this is a cultural difference, and we should code it as such.

When I think of people who ‘relentlessly steer conversation toward one topic’ I think of certain neurodiverse individuals, their disabilities around pragmatics and the joy they derive from deep and special interests. When it comes to hobbies, hobbies which involve collecting things are seen as creepy. (And more creepy still when the item collected is related to death or sex in some way. Collecting dolls is also widely considered creepy.) Neurodiverse people with special interests often collect items related to that special interest.

Watching something as a hobby is also considered creepy, including bird watching.

Should we really consider such hobbies creepy? Bird watching harms no one.

In The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker encourages us all to trust our instincts when assessing potentially dangerous people. He’s not wrong about that, and I’ve recommended his book to many people.

“intuition is always right in at least two important ways;

Gavin De Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

It is always in response to something.

it always has your best interest at heart”

“Only human beings can look directly at something, have all the information they need to make an accurate prediction, perhaps even momentarily make the accurate prediction, and then say that it isn’t so.”

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear: Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

At the same time, our assessment of ‘creepy’ has been shaped by our exposure to narrative (cultural and in fiction), and also by our own prejudices and lack of awareness of different cultures and neurodiversity.

Perhaps this goes some way toward explaining why young people are more likely to be creeped out than older people, who have seen a broader range of individuals, and are therefore more likely to sense the main factor behind creepiness: ‘ambiguity’.

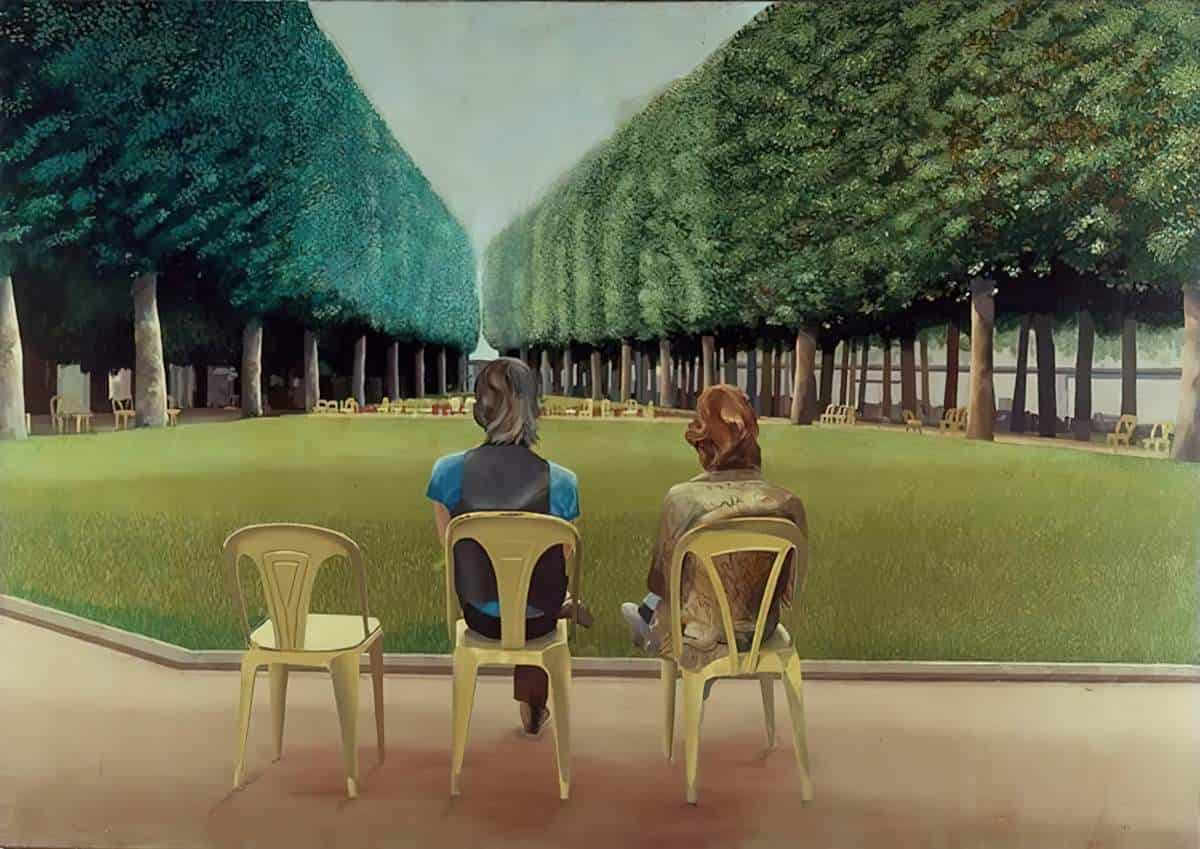

CREEPINESS AND ASYMMETRY

When artwork is nowhere near symmetrical and we don’t expect symmetry, that’s not creepy. Perfect symmetry is also not creepy. But once the artwork approaches symmetry then messes with it a little, now the viewer is plunged into an uncanny valley of symmetry: We espect symmetry, but don’t get it.

The illustration below by David Hockney is the perfect example of creepy asymmetry.

CREEPINESS AND CAMERA ANGLE

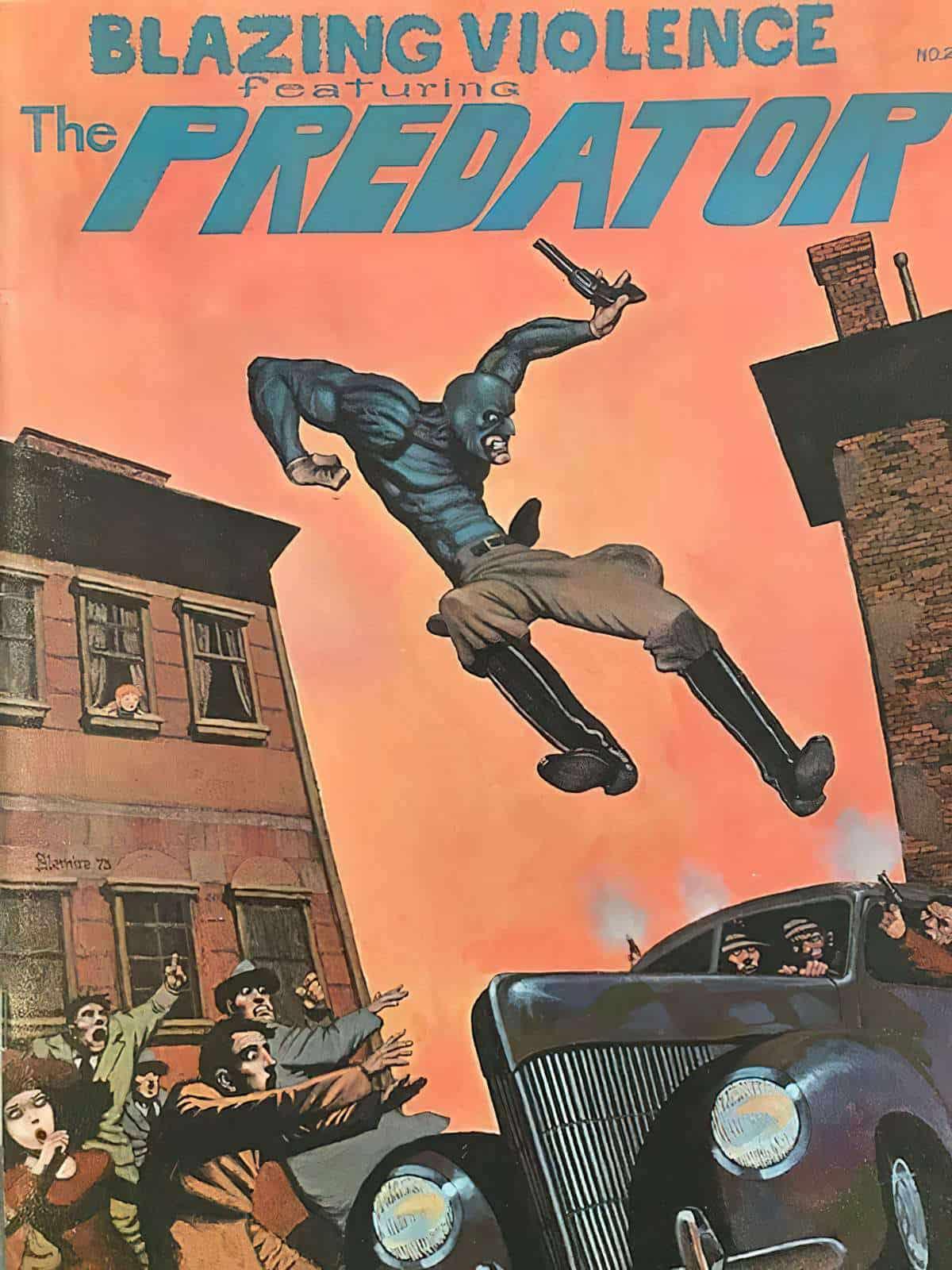

In static imagery, a low angle shot can add to the creepiness, as demonstrated by the following cover illustration, aided by its off-kilter perspective.

DISCUSS

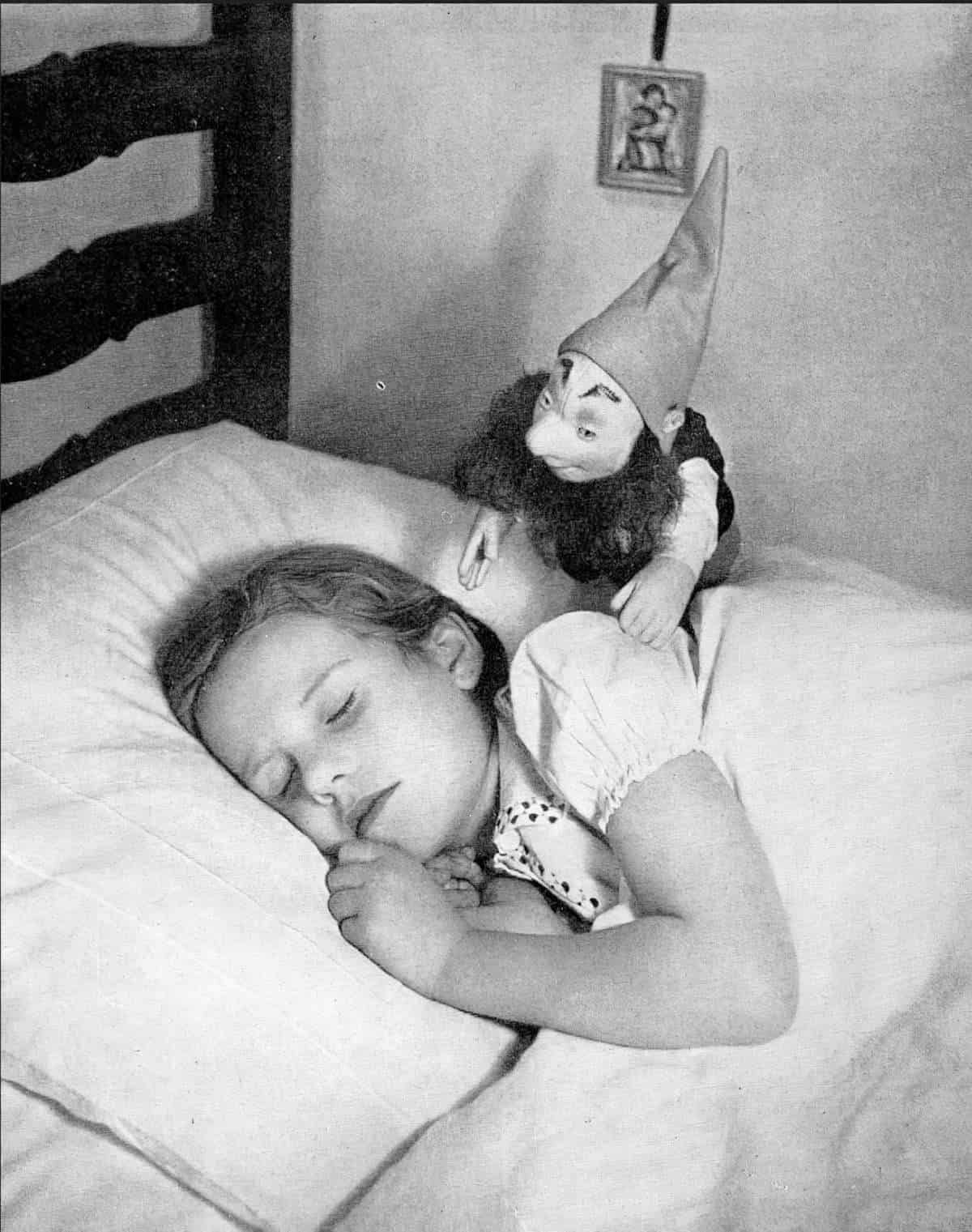

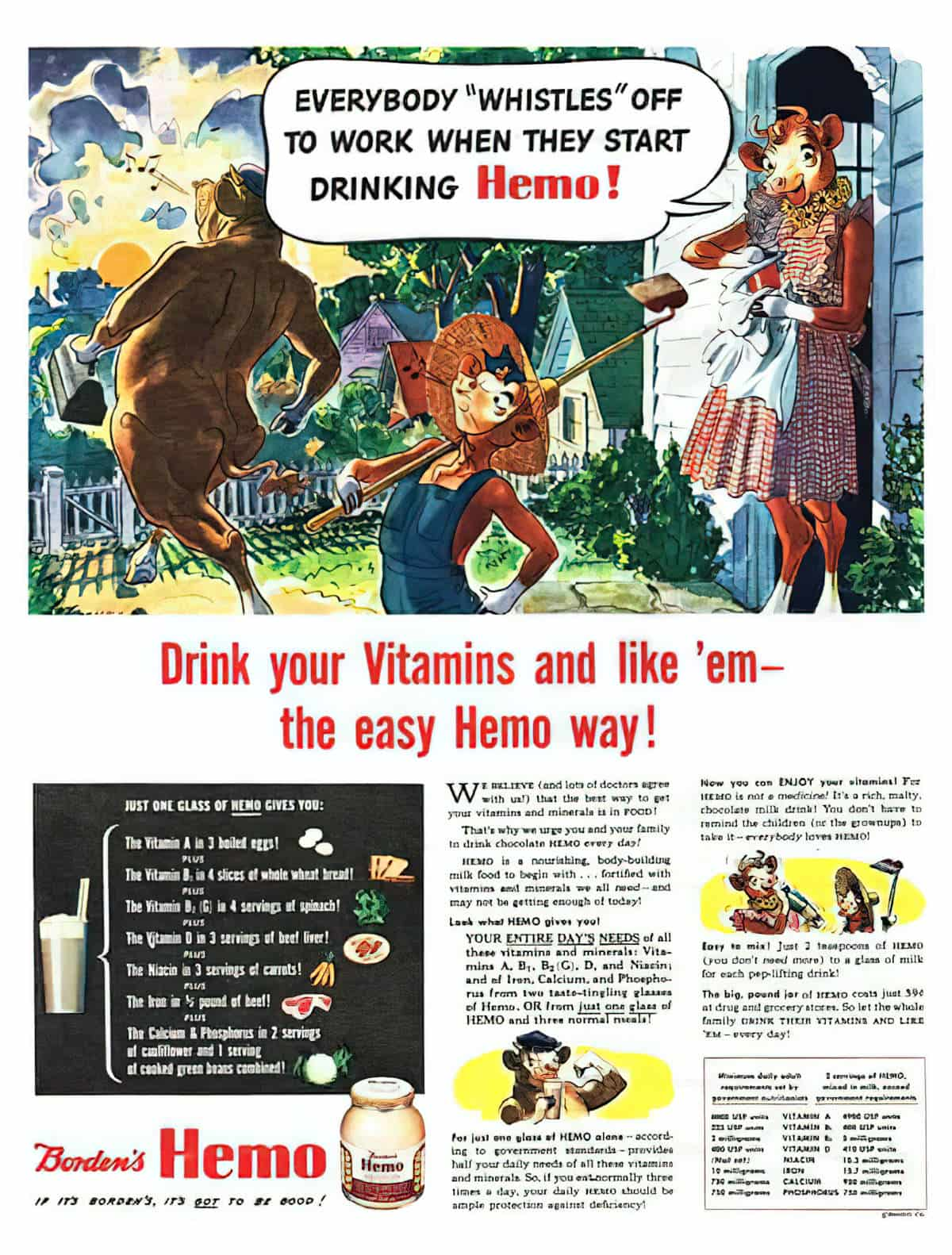

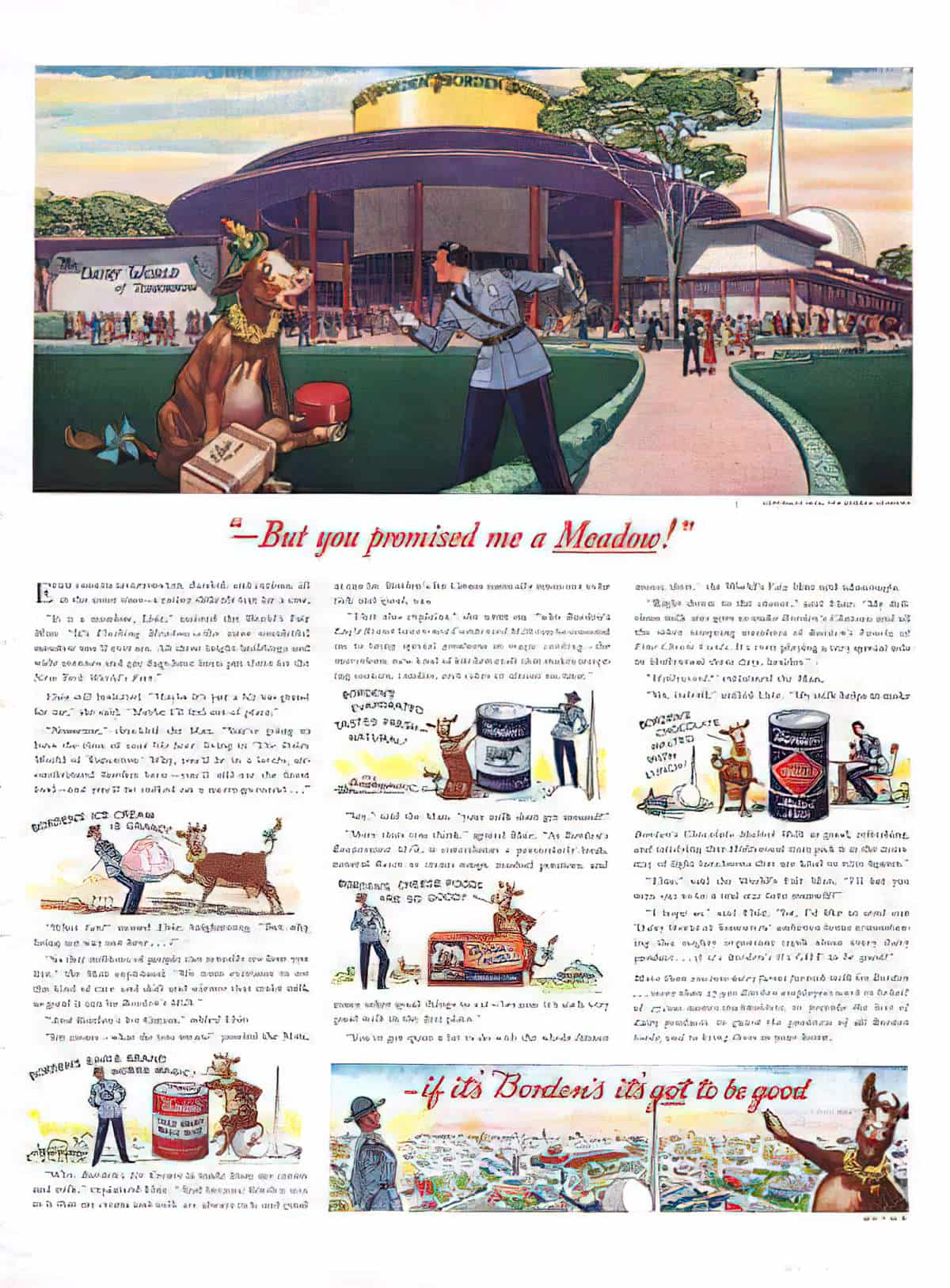

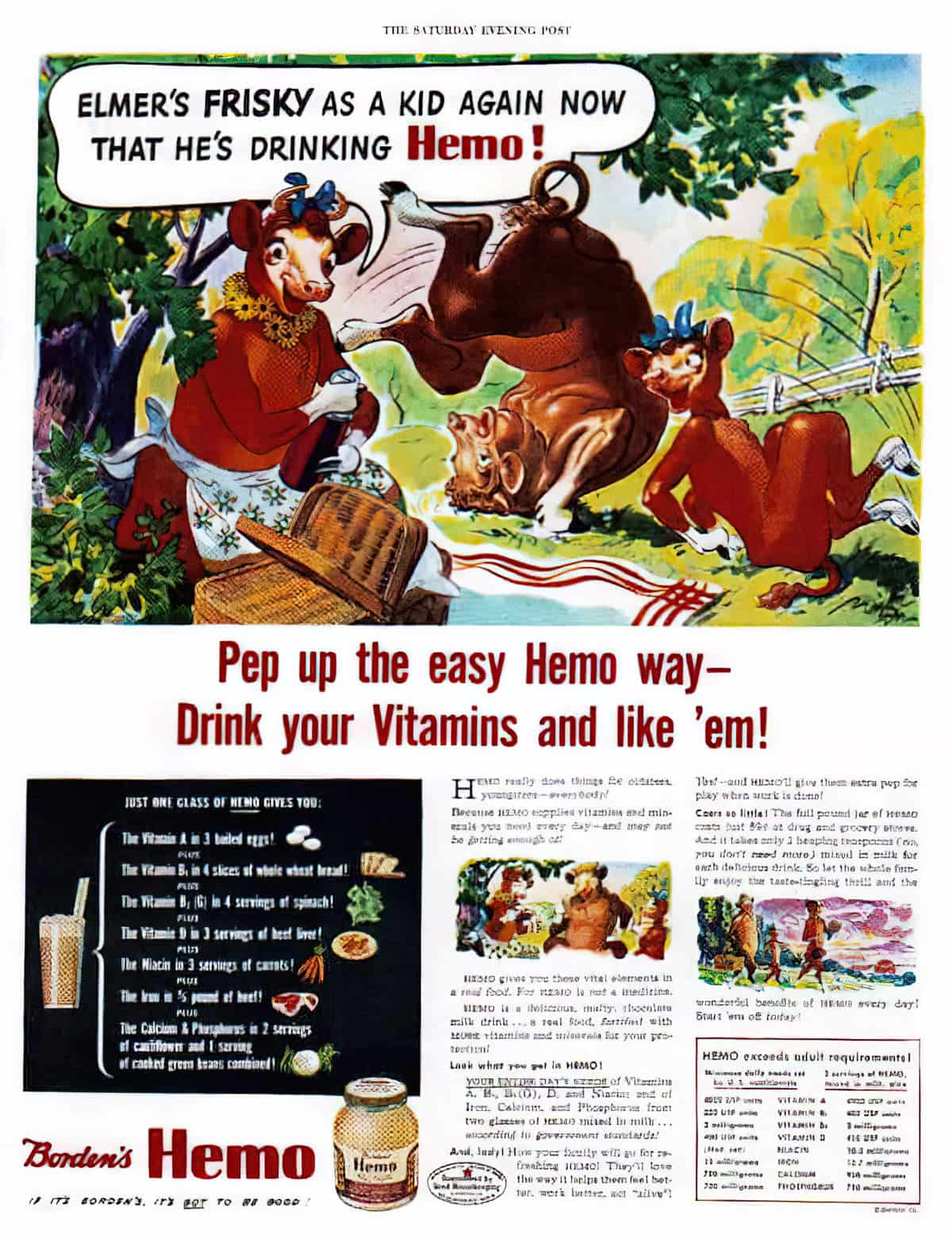

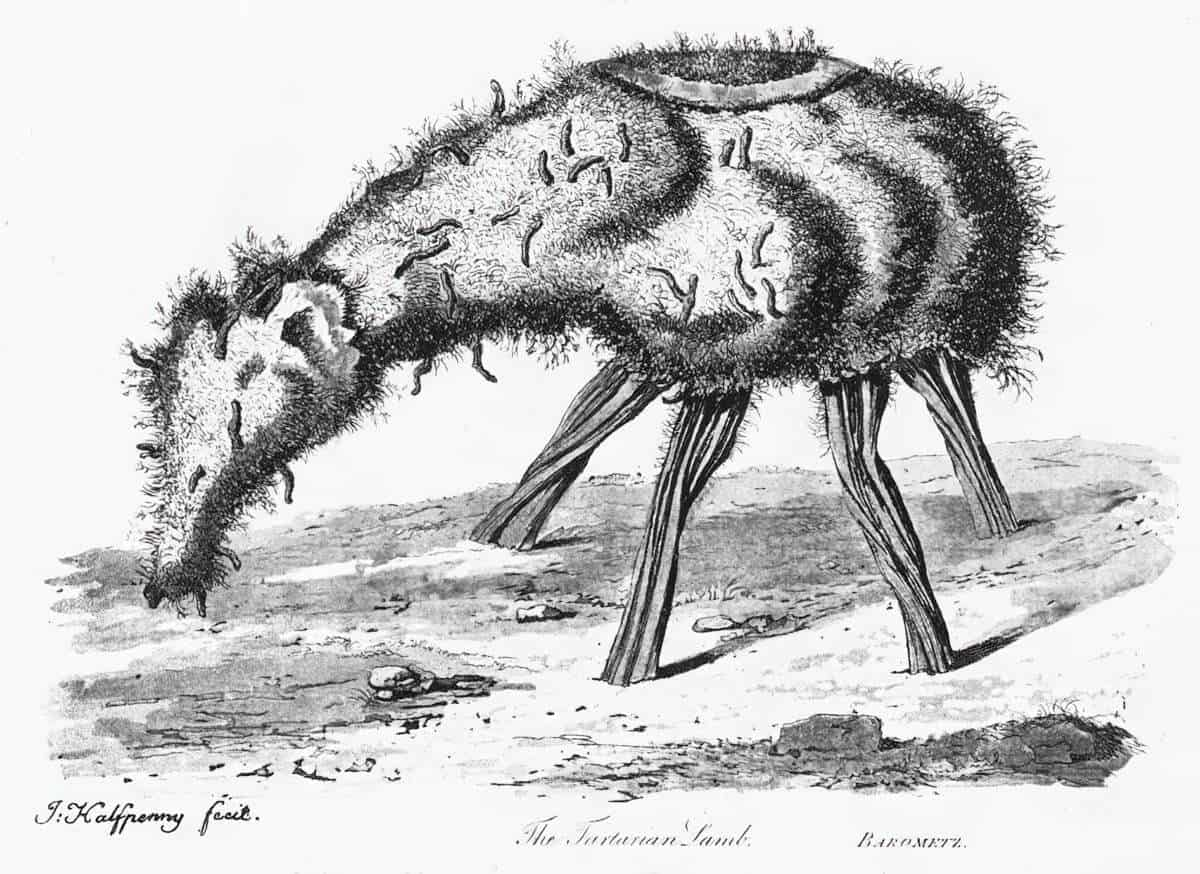

Does the following creep you out and if not, why the hell not? What happened to you?

Also: What makes it creepy? Be specific.

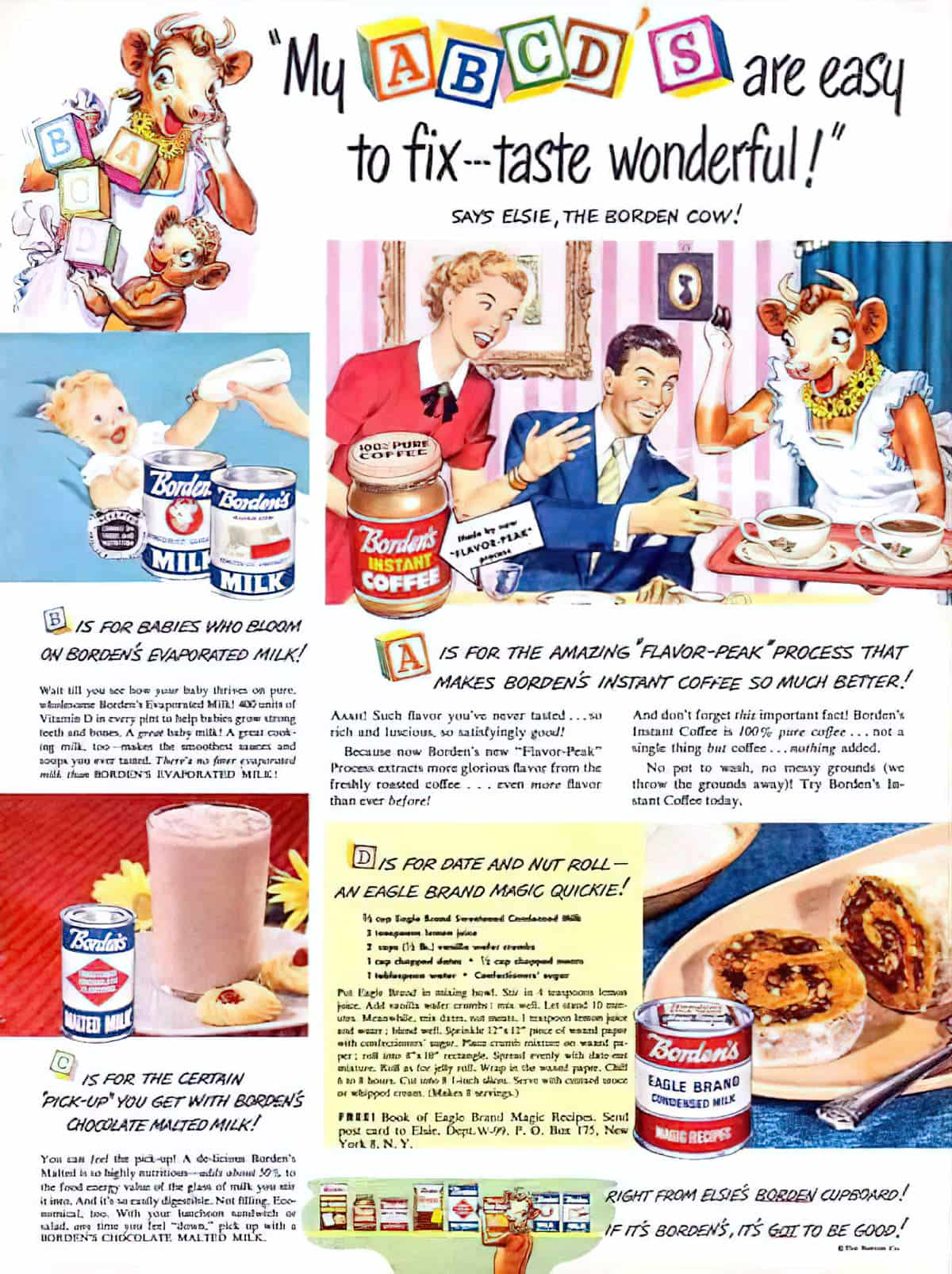

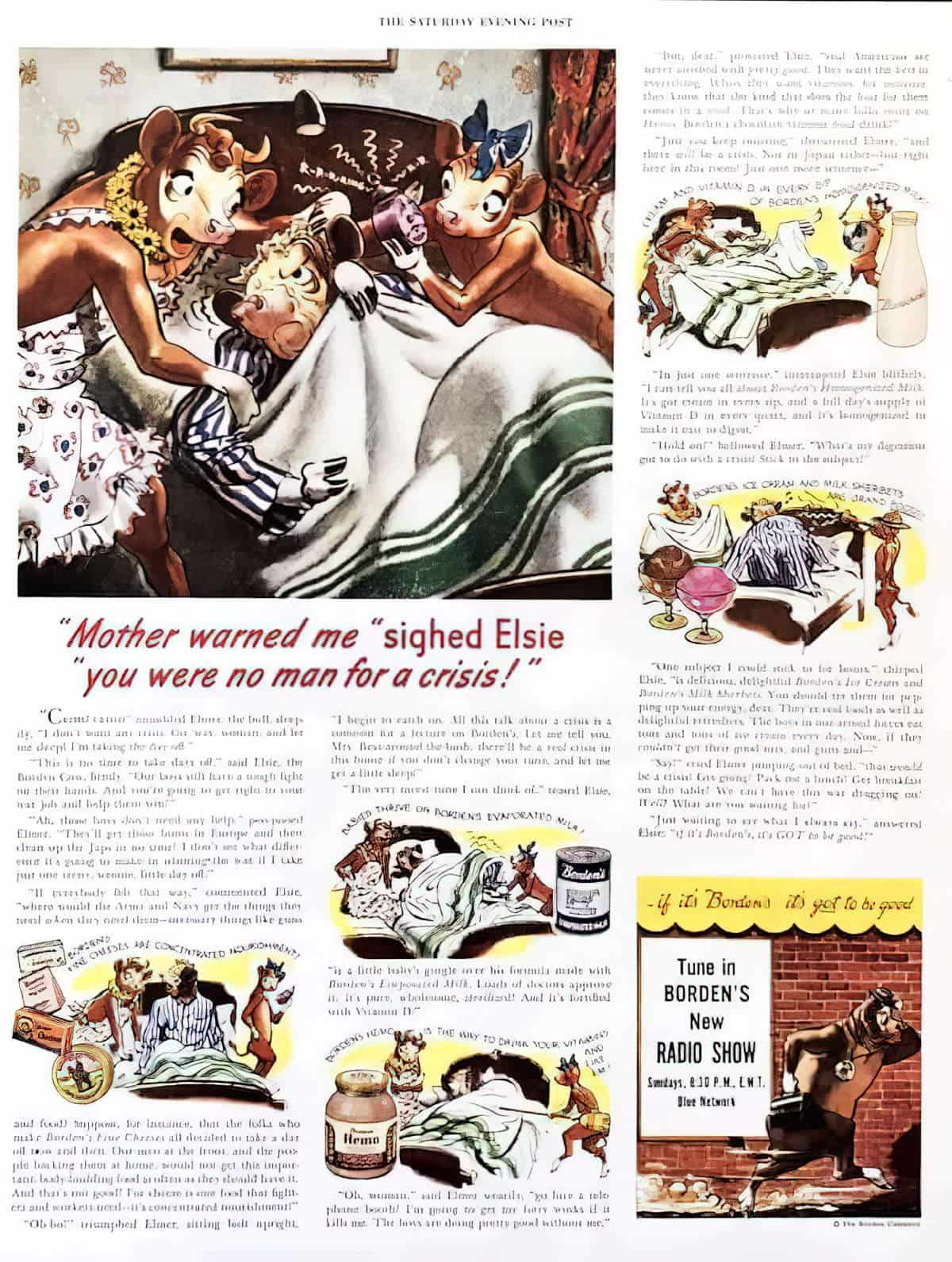

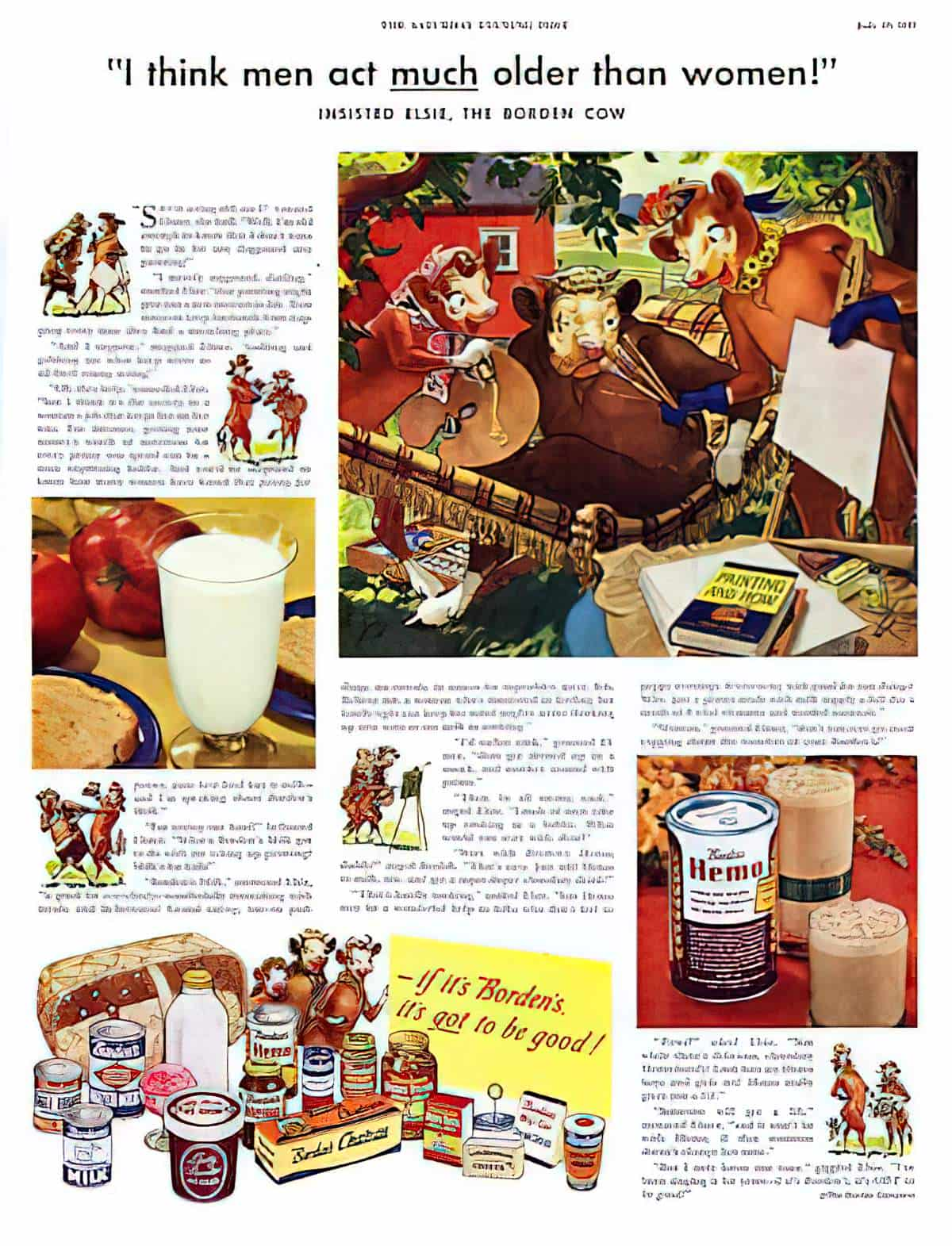

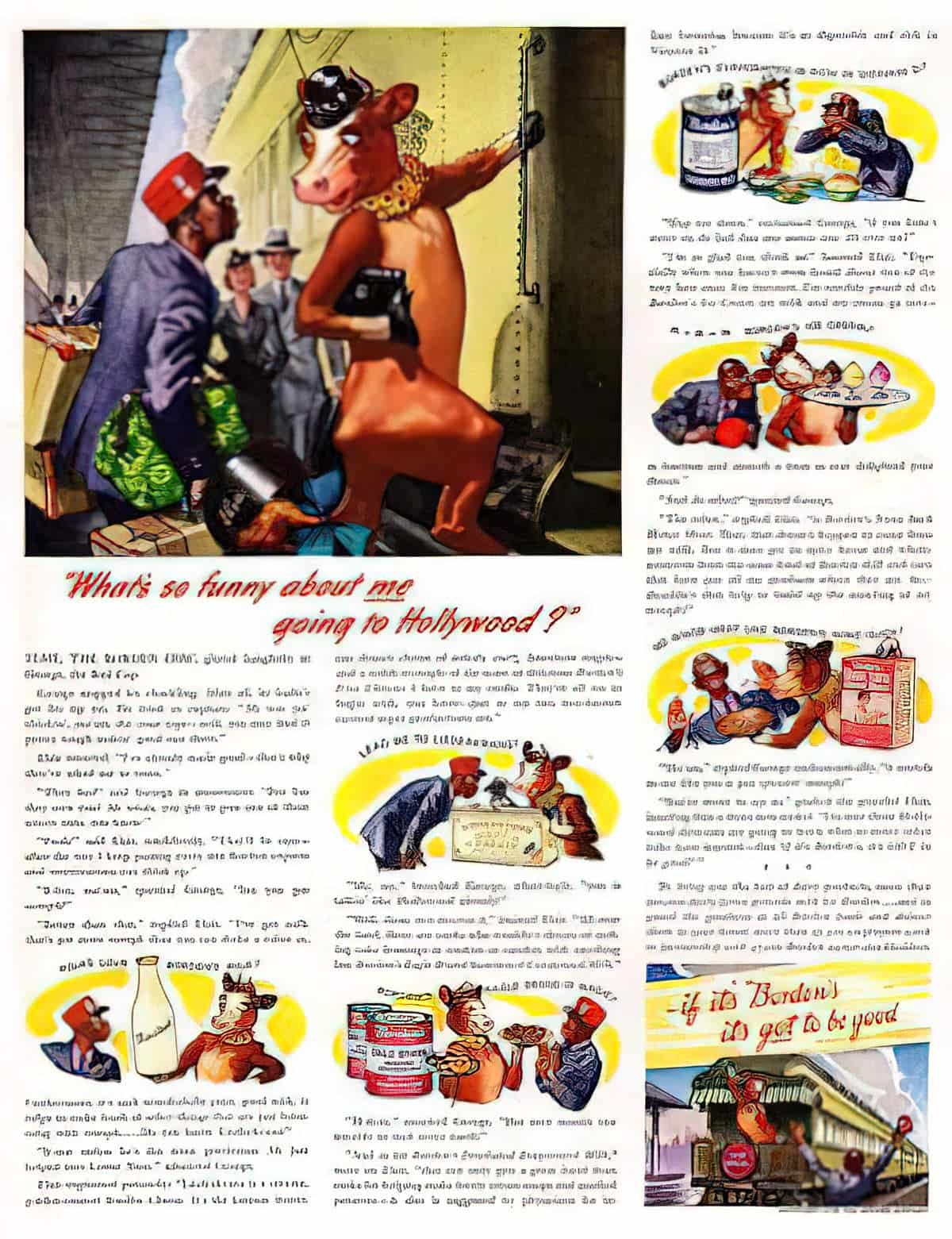

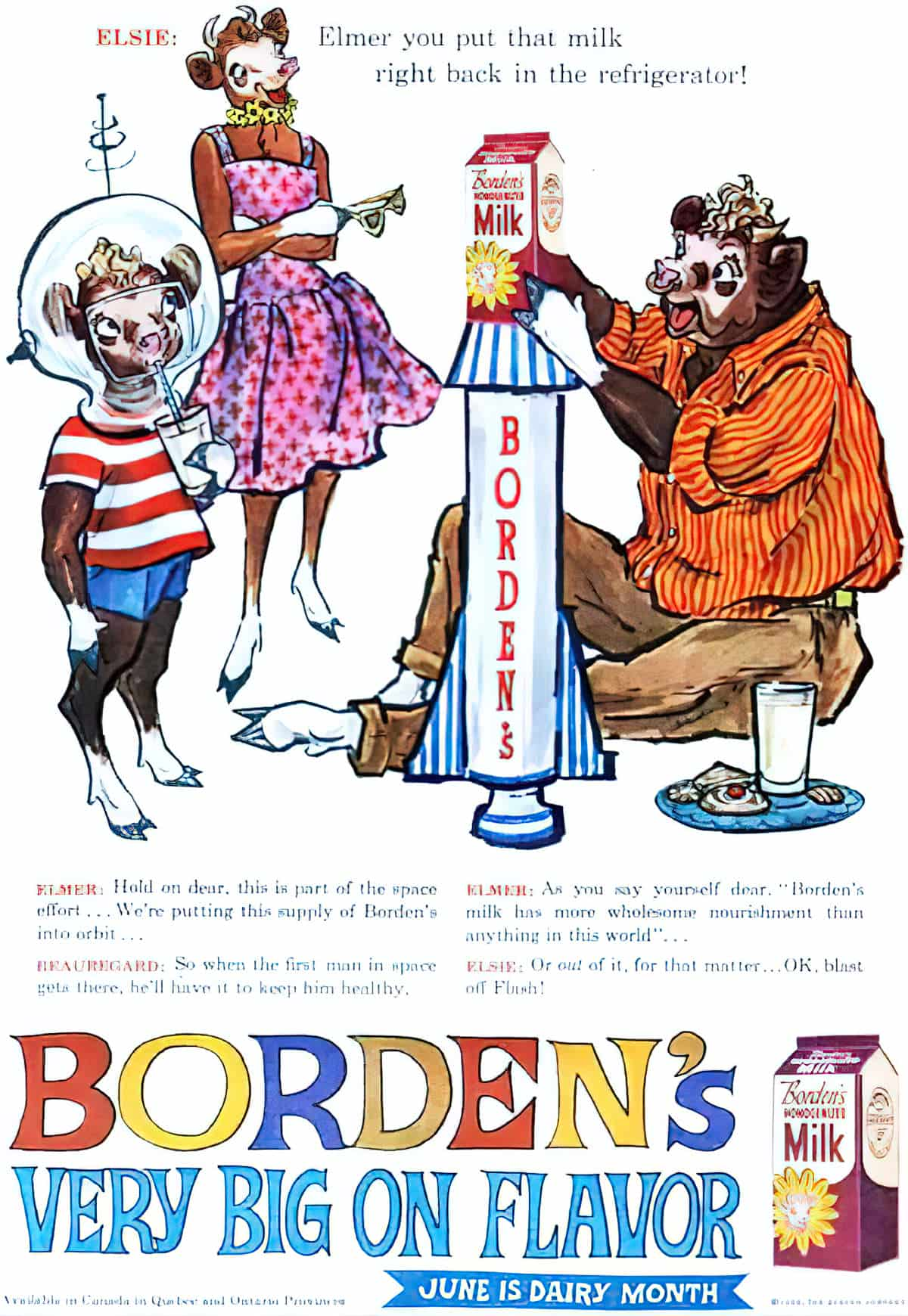

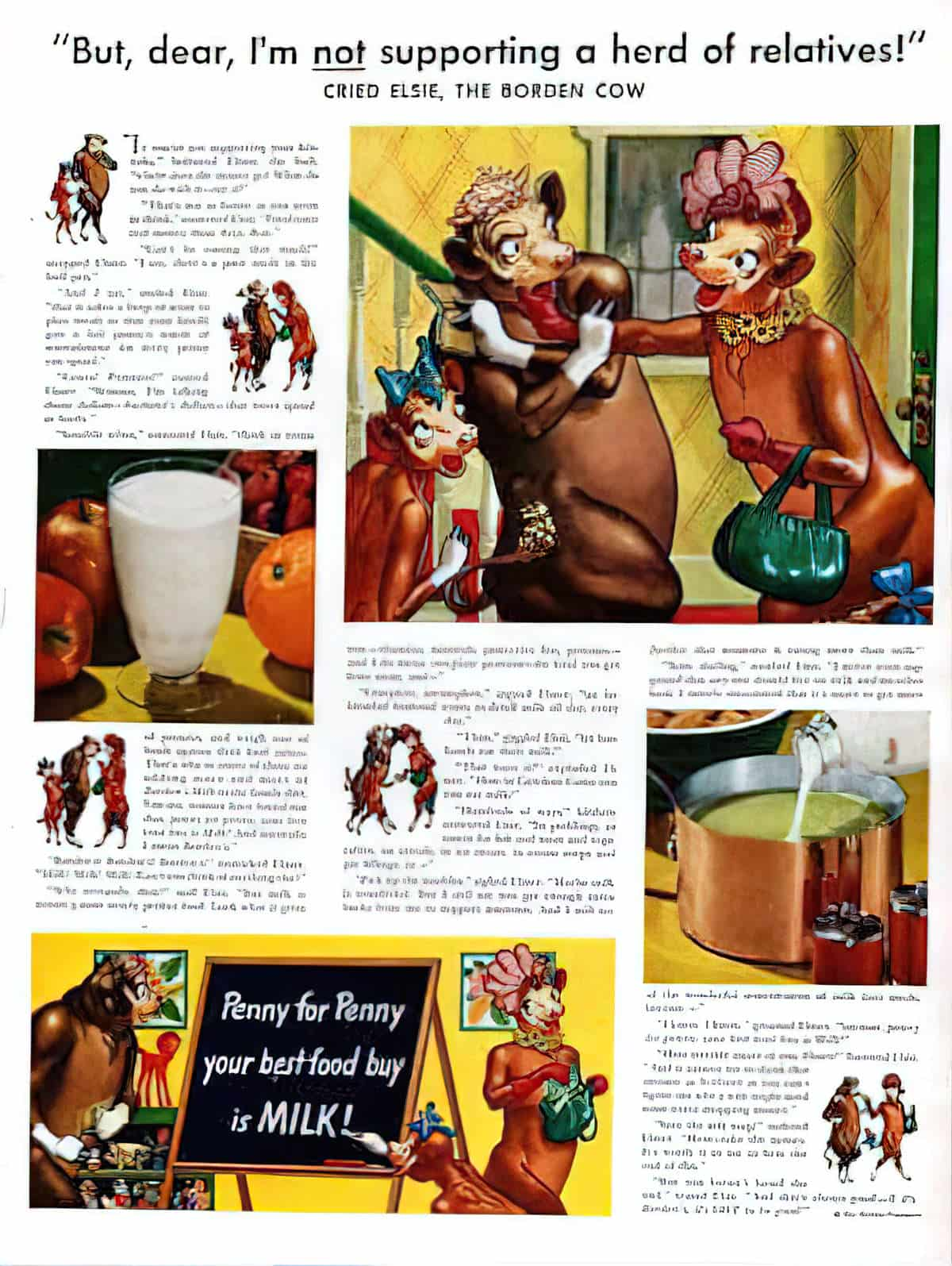

Ward created a long series of ads featuring Elsie the Cow and her family. Elsie was seen in advertising campaigns for over 30 years, but she was never able to make the transition to television. (I wonder why.)

She was created in 1936, when the dairy industry saw highly-publicised price wars between farmers and dairy processors that caused larger dairies to be portrayed unfavorably. (Walter Early drew the first Elsie the Cow cartoon, which makes his name aptronymic.) The company first started advertising in medical journals, which featured a variety of cartoon cows with several different names, including Mrs. Blossom, Bessie, Clara and Elsie. A typical ad showed a cow and calf talking in a milk barn.

Except for the rare promotional appearance, she was retired in the late 1960s. However, Borden’s kept her image on their products. Over the following years she went through a few changes, arguably becoming creepier and creepier. This cow could already talk, but she was subsequently given the ability to stand upright. Eventually she became a creepy admixture of cow and housewife.

Header illustration: “Two Dancing Fools” by Hendrick Hondius (I), after Pieter Bruegel (I), 1642. The image reminds me of illustrations of the Wild Things by Maurice Sendak. Sure, they’re fools and they’re only dancing, but they are also very creepy.

SEE ALSO

The Everything Is Creepy podcast

Fantasia 2016 — a review of Creepy (2016) by Kiyoshi Kurosawa