To a modern audience, what makes a setting feel ‘fairytale’? What is it about the tone, style and plot? I argue here that what makes a fairytale setting feel ‘fairytale’ is mostly the ‘fairytale logic’.

Just as we know, almost intuitively, that a particular narrative is a fairy tale when we read it, it seems we know immediately that a particular film is a fairy tale when we see it.

Jack Zipes (1996)

[Fairy tales display a distinctive quality] in the sense of a characteristic, instantly recognizable feel or style […] recognizable in the level of structure and content as much as language.

Jessica Tiffin (2009)

Every culture has its own fairytales, but I must limit myself to the European notion of a fairytale setting, in which case: Europe. These are the fairytales which have influenced me the most.

Fairytale scholars would like us to know that fairytales change and evolve over time and we should avoid phrases such as ‘the original Snow White’ etc. because there’s really no such thing. There can be no ‘Snow White setting’, either. Fairytales are not a timeless, ageless tradition. With that caveat, and the acknowledgement that modern fairytales will one day look like ancient, unfamiliar and magical to audiences of our distant future, what does ‘fairytale setting’ mean to us, right now, in the West?

Fairytale Colour

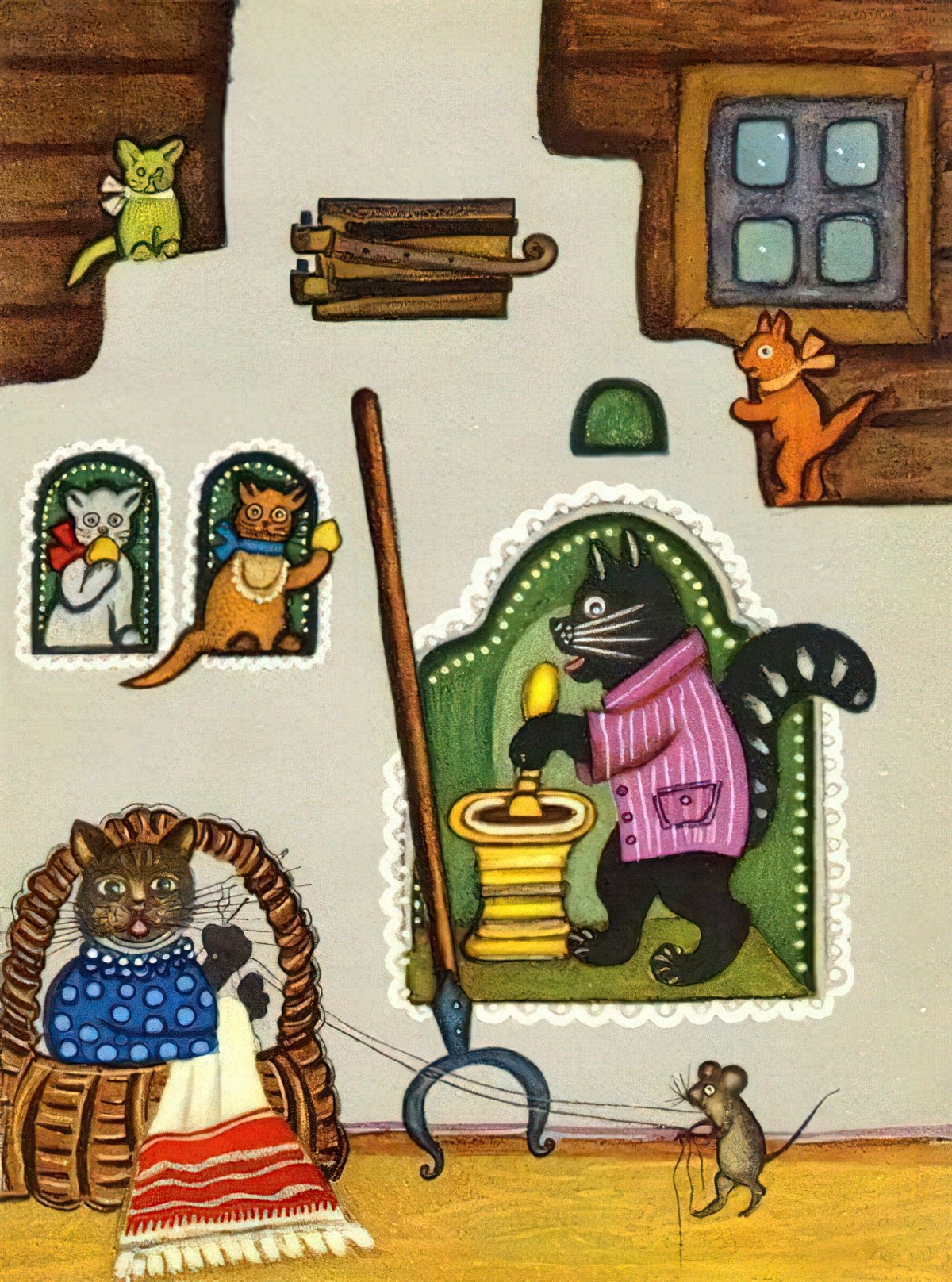

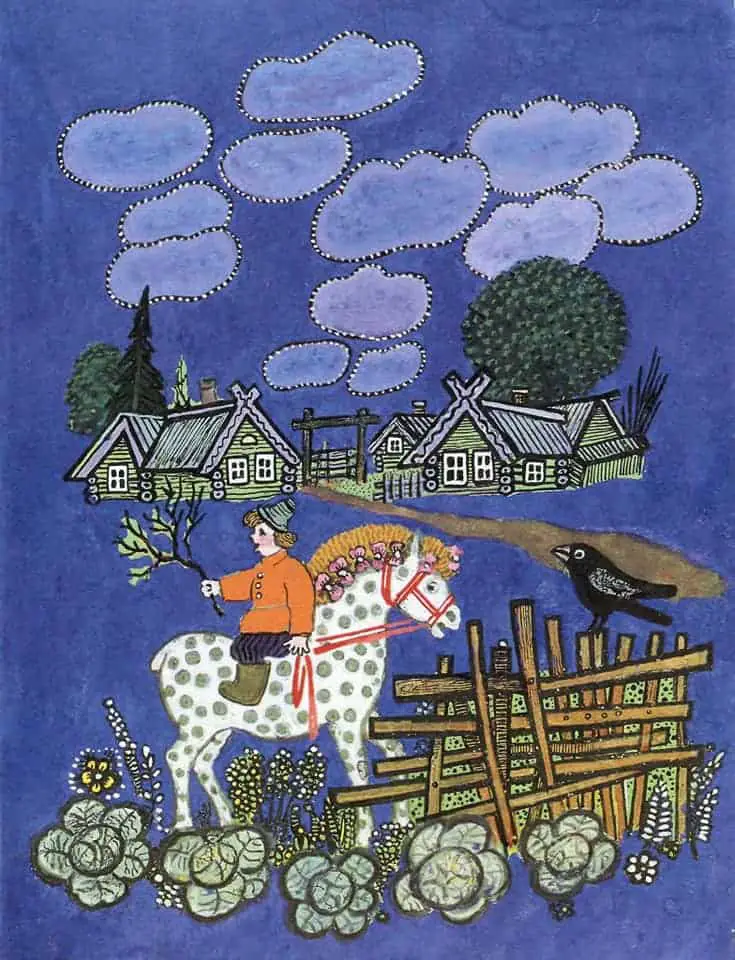

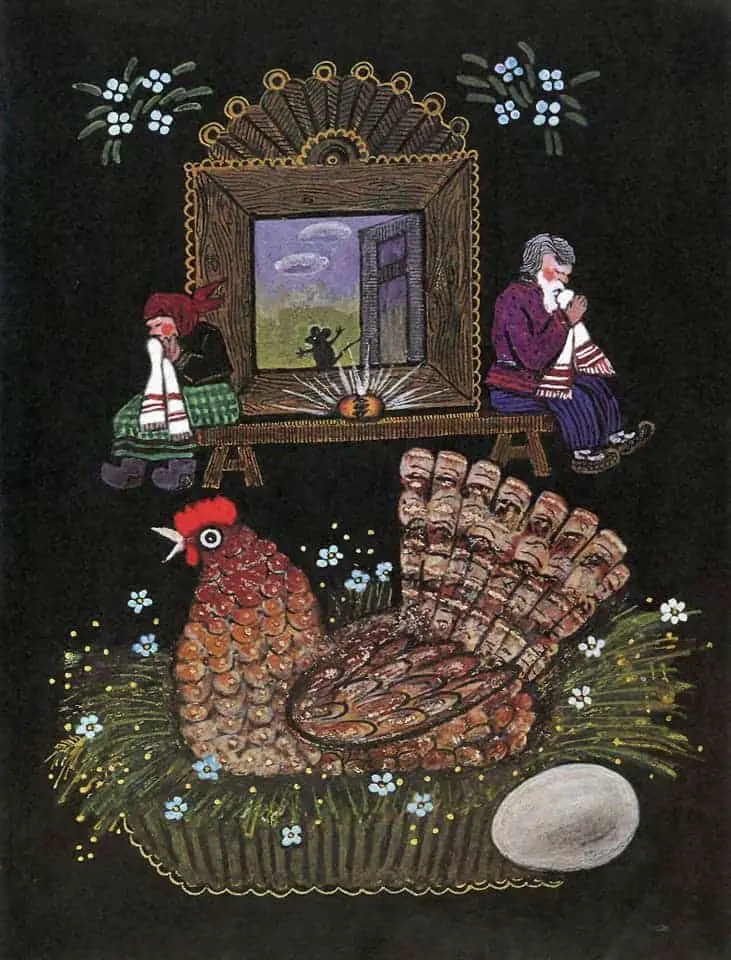

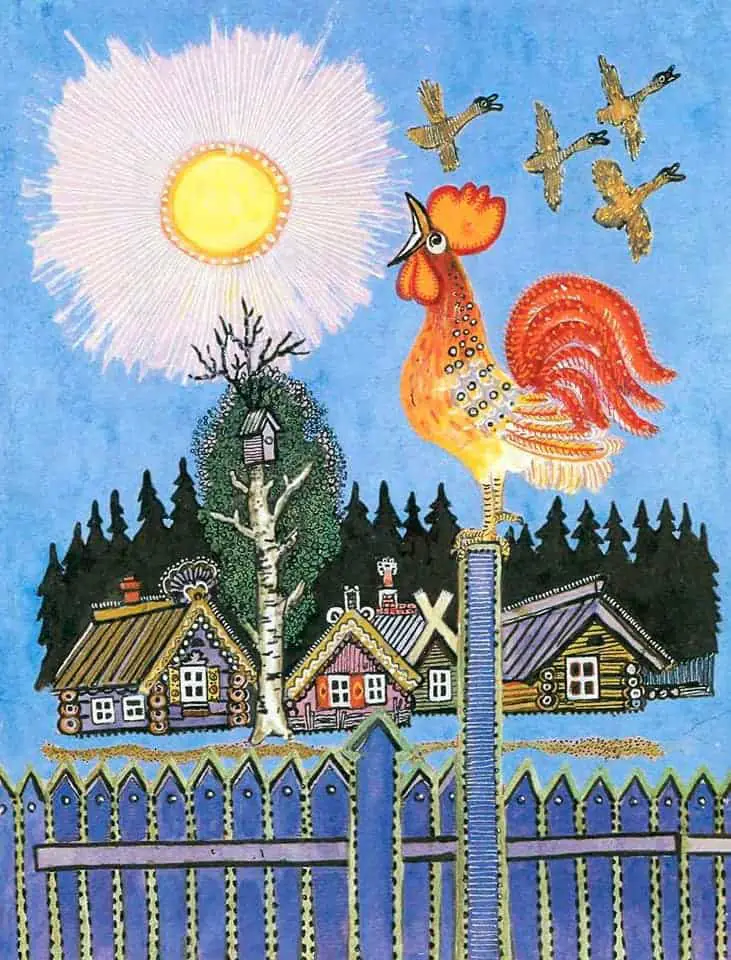

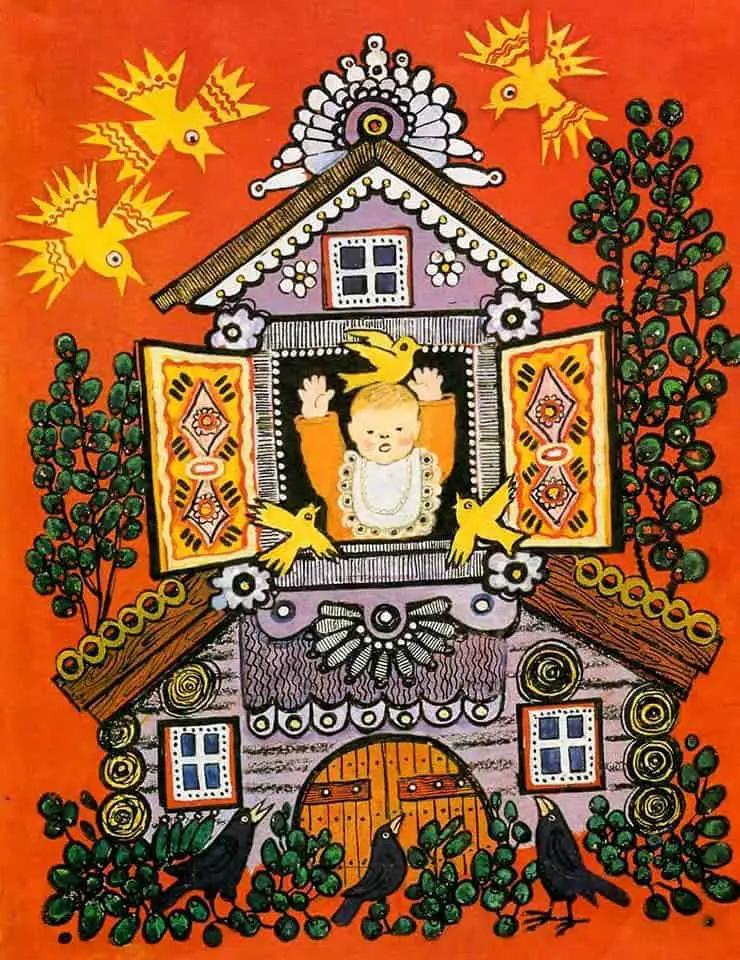

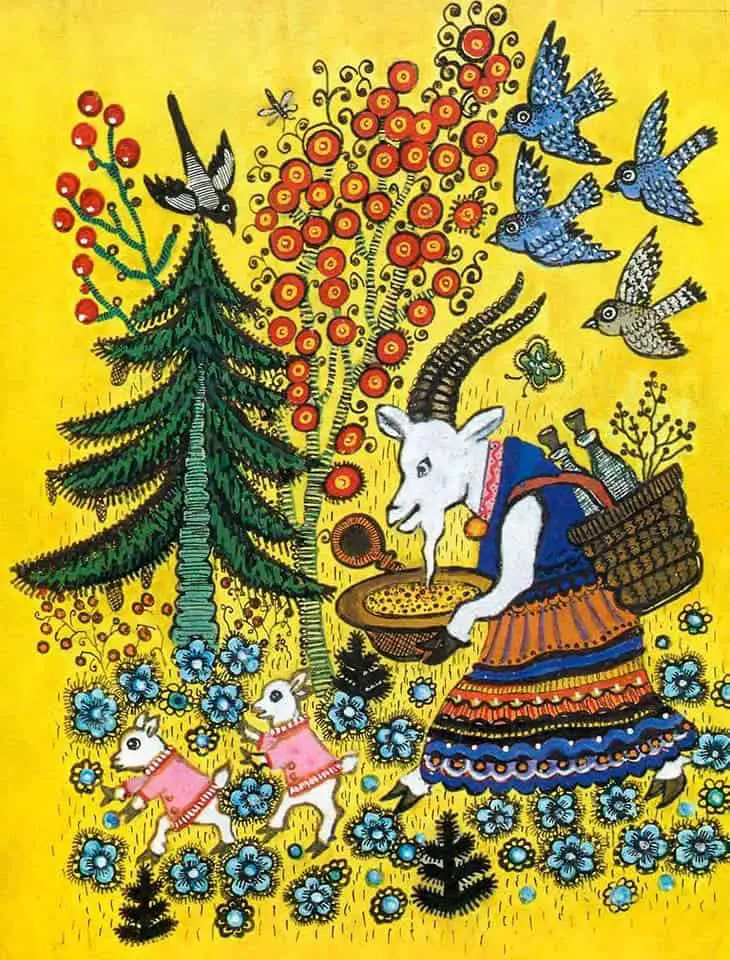

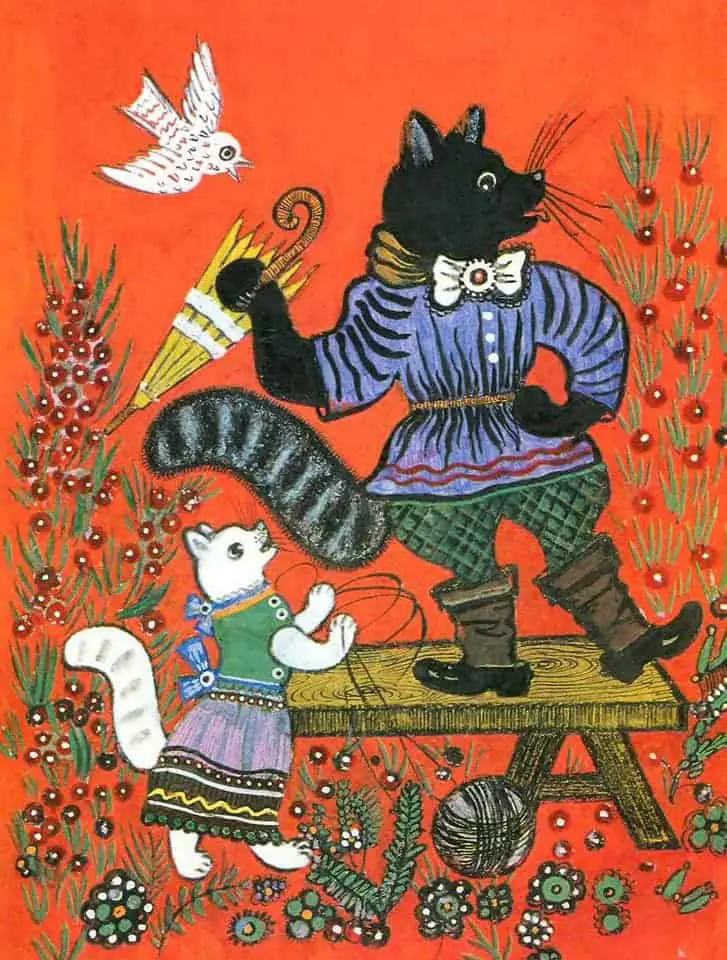

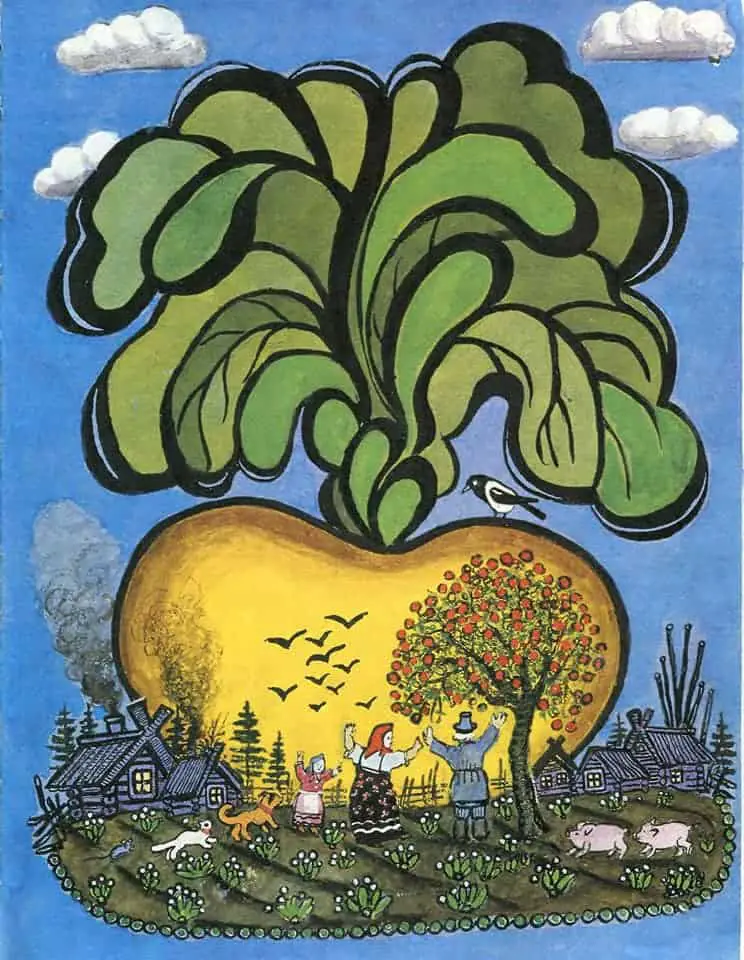

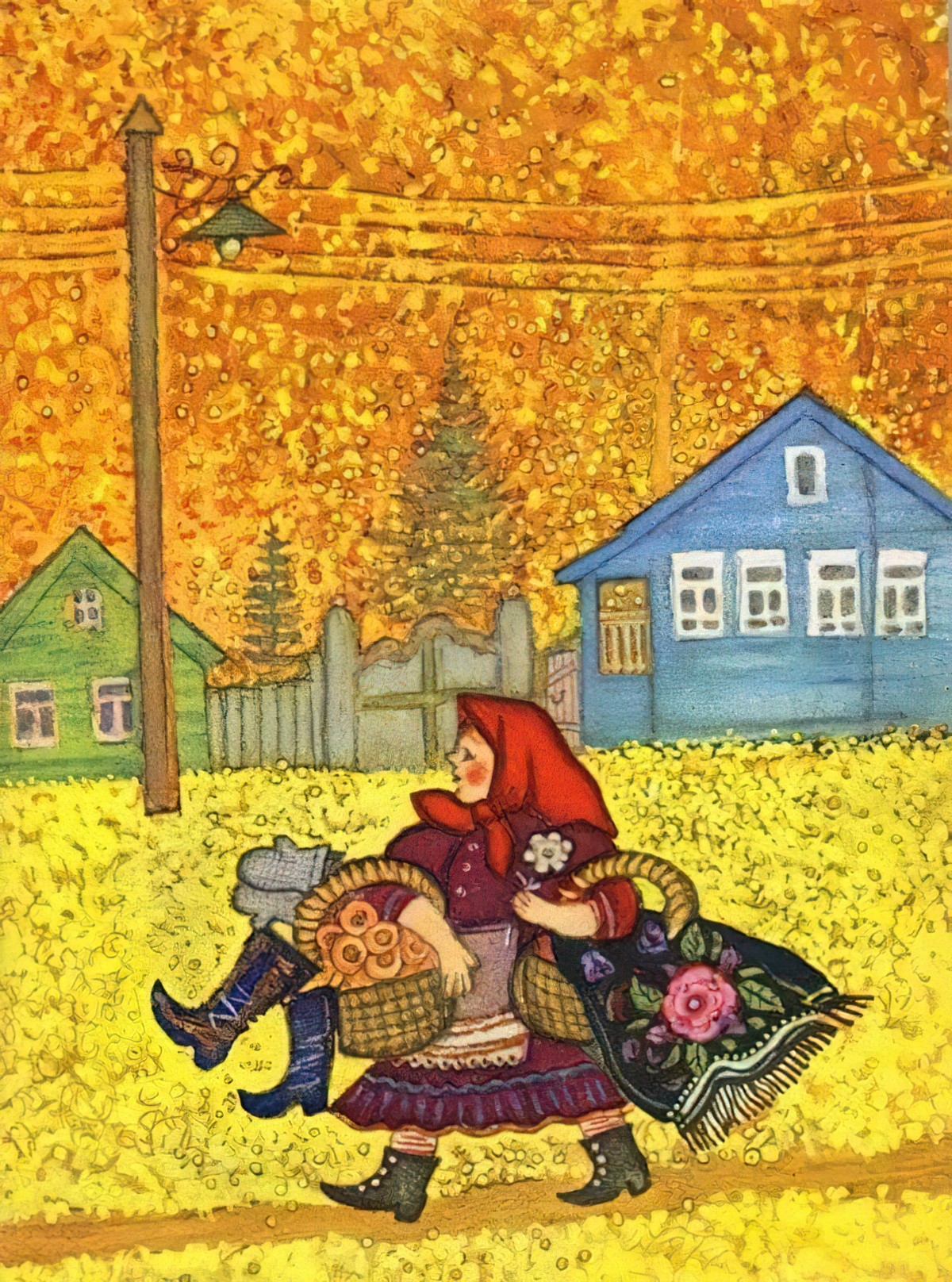

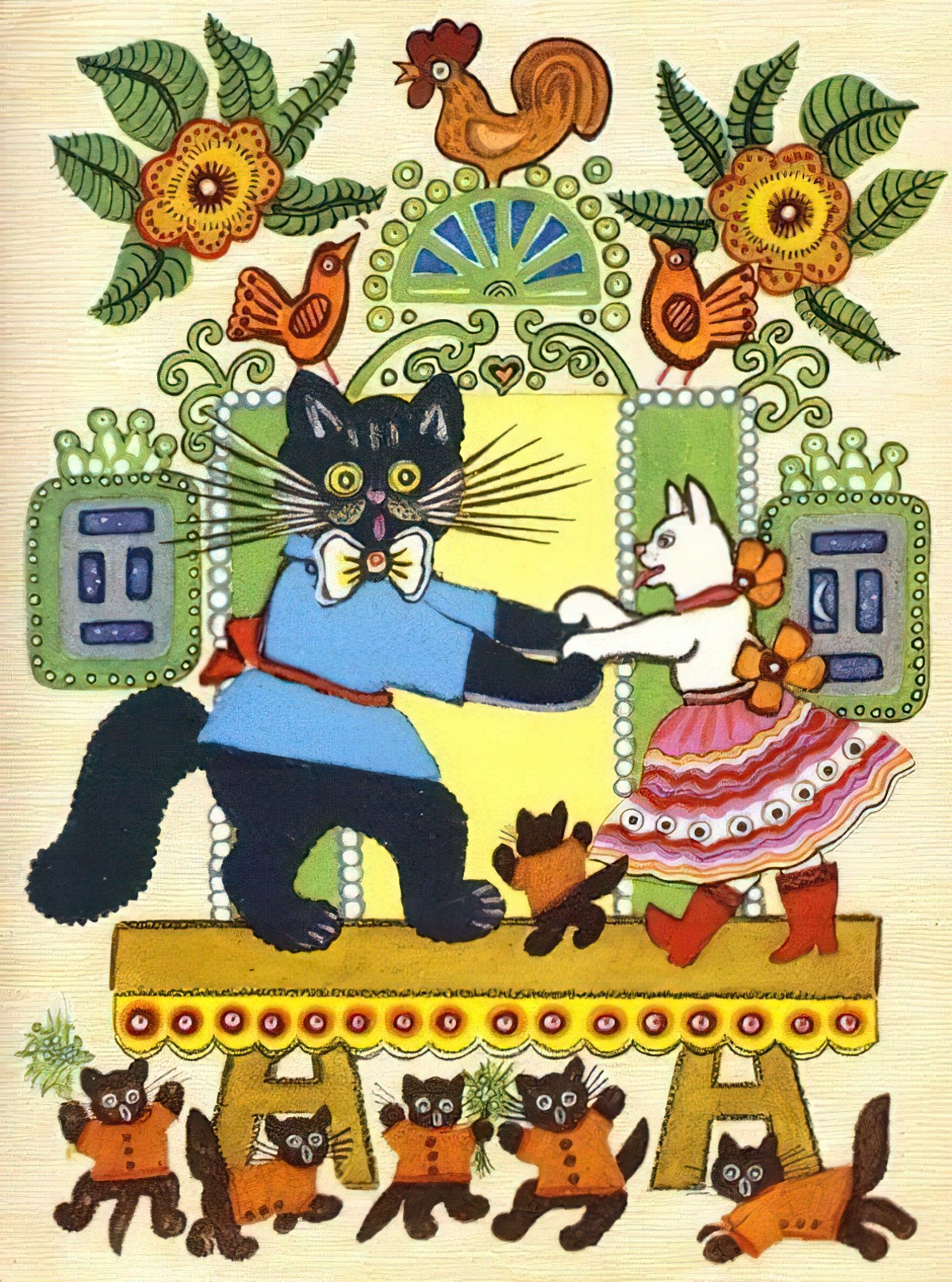

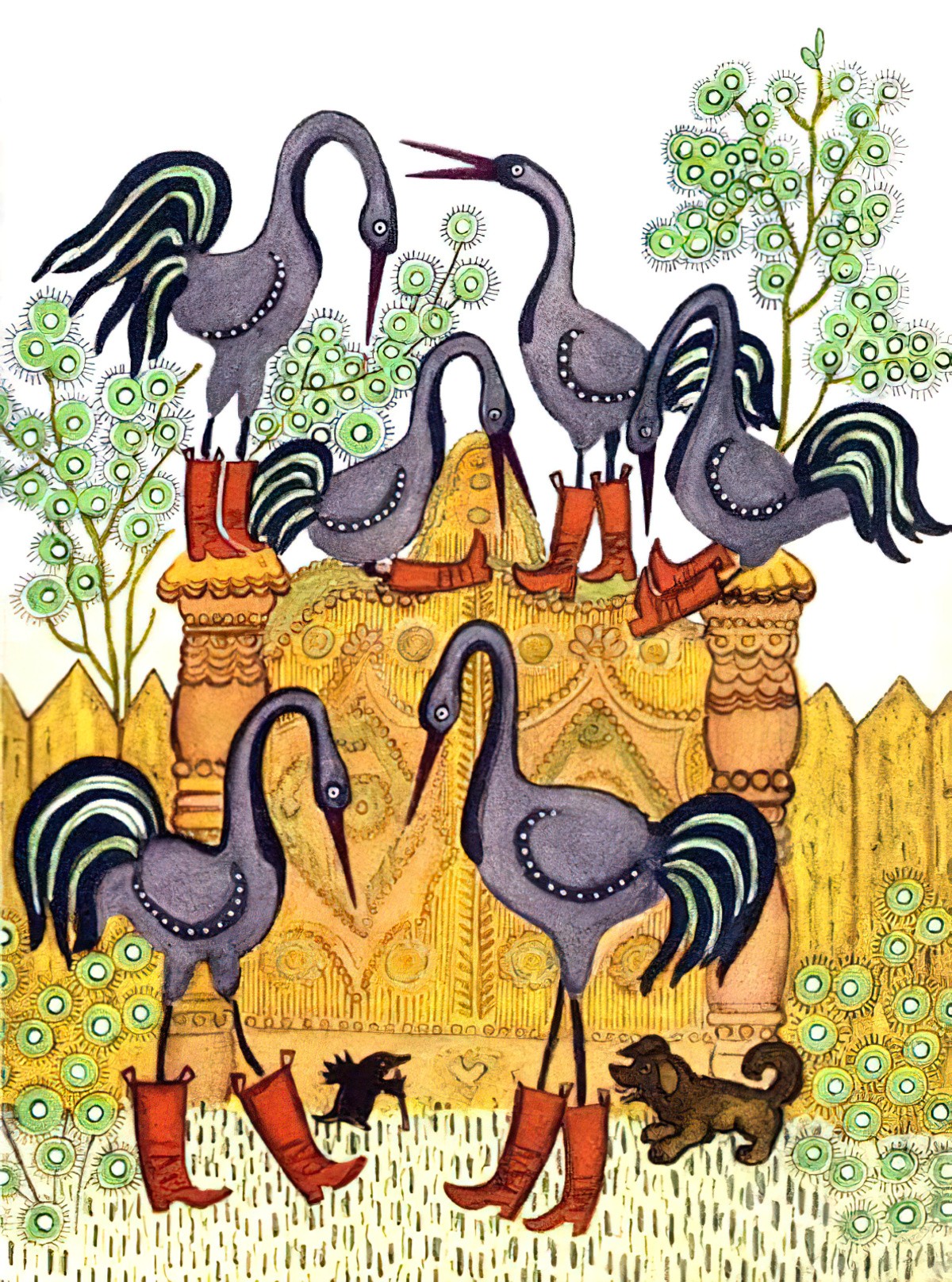

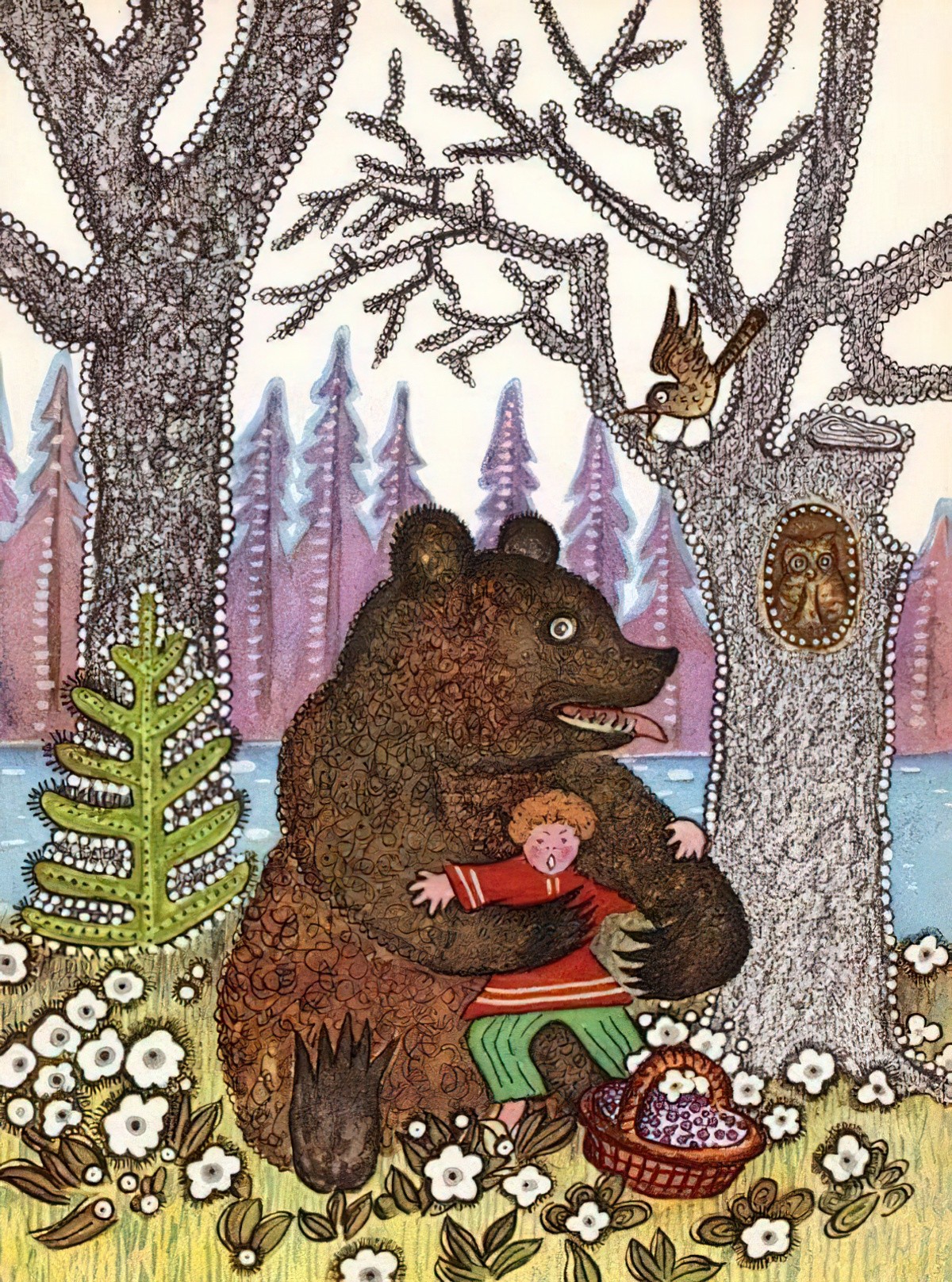

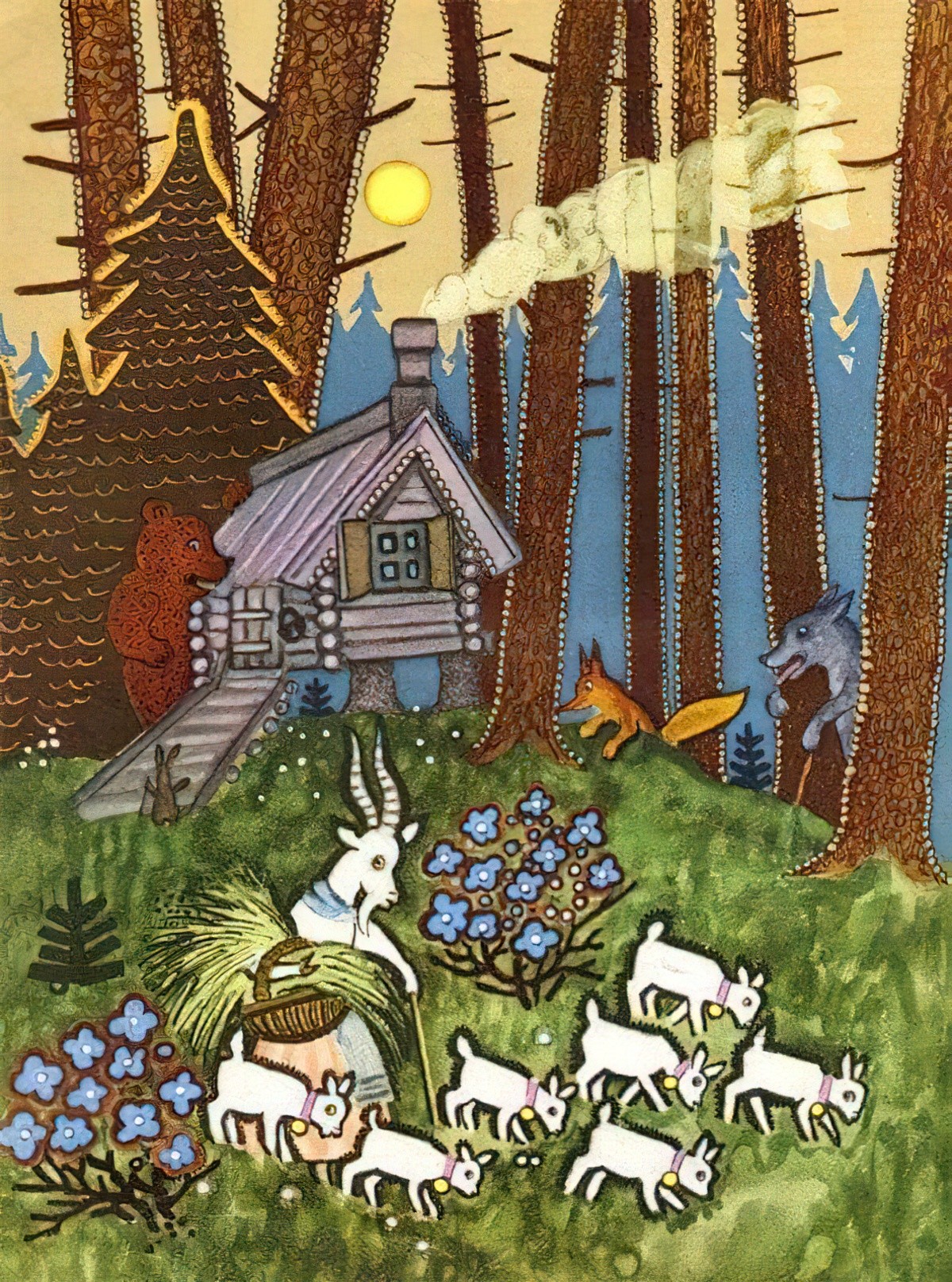

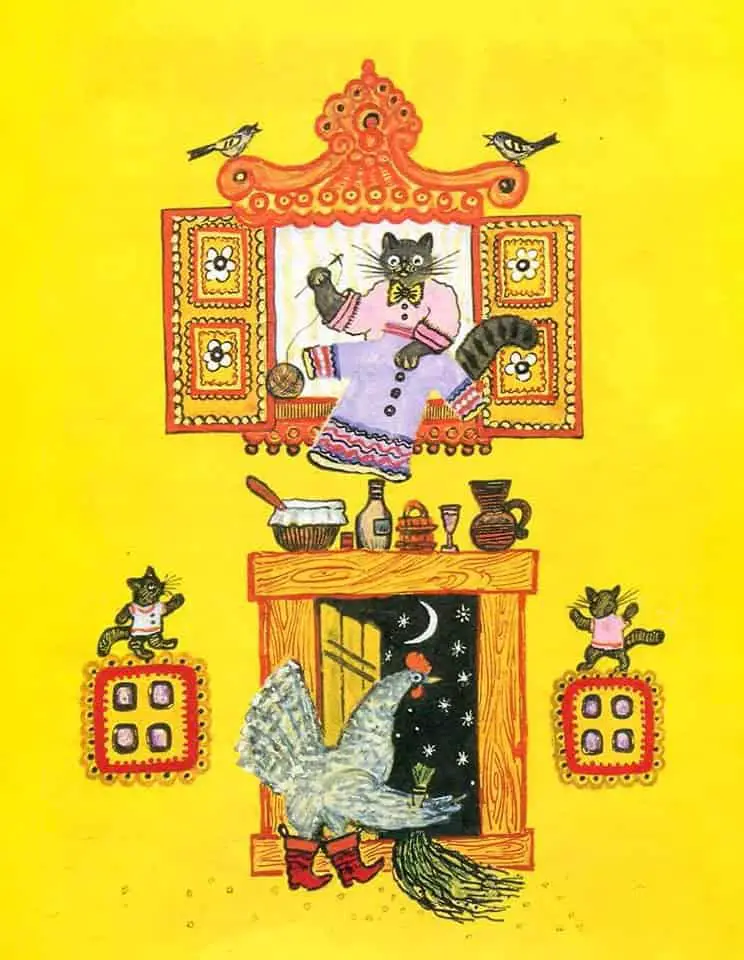

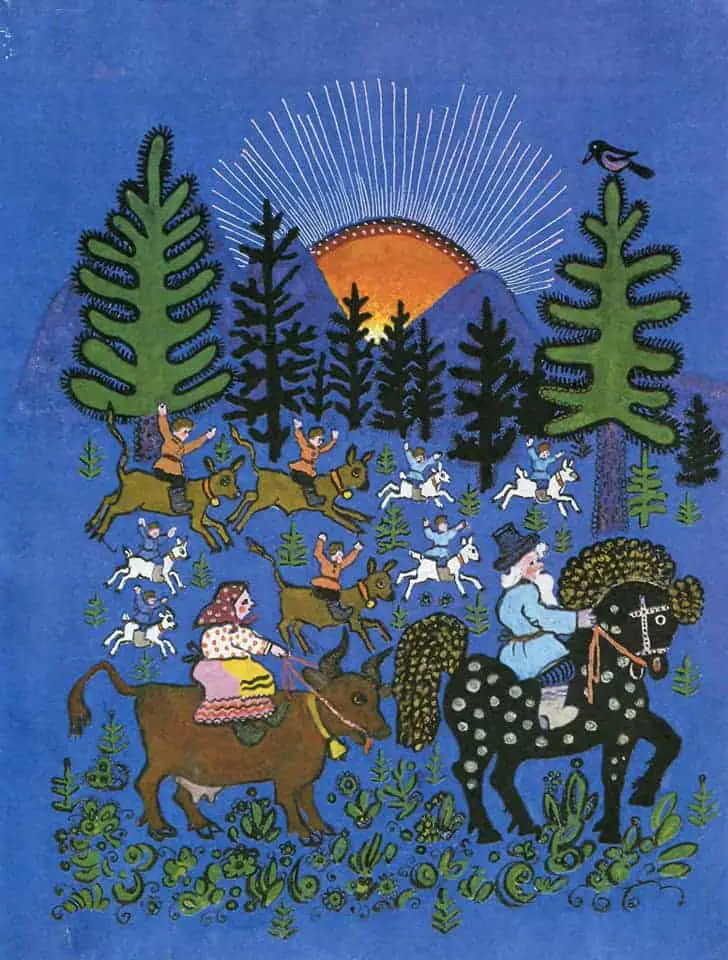

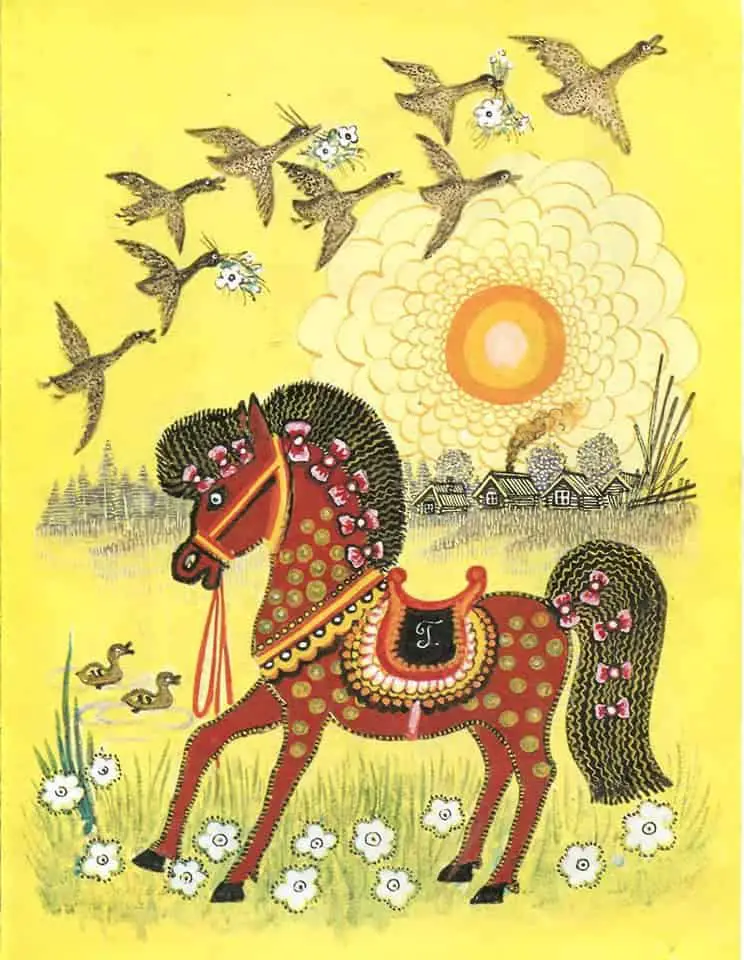

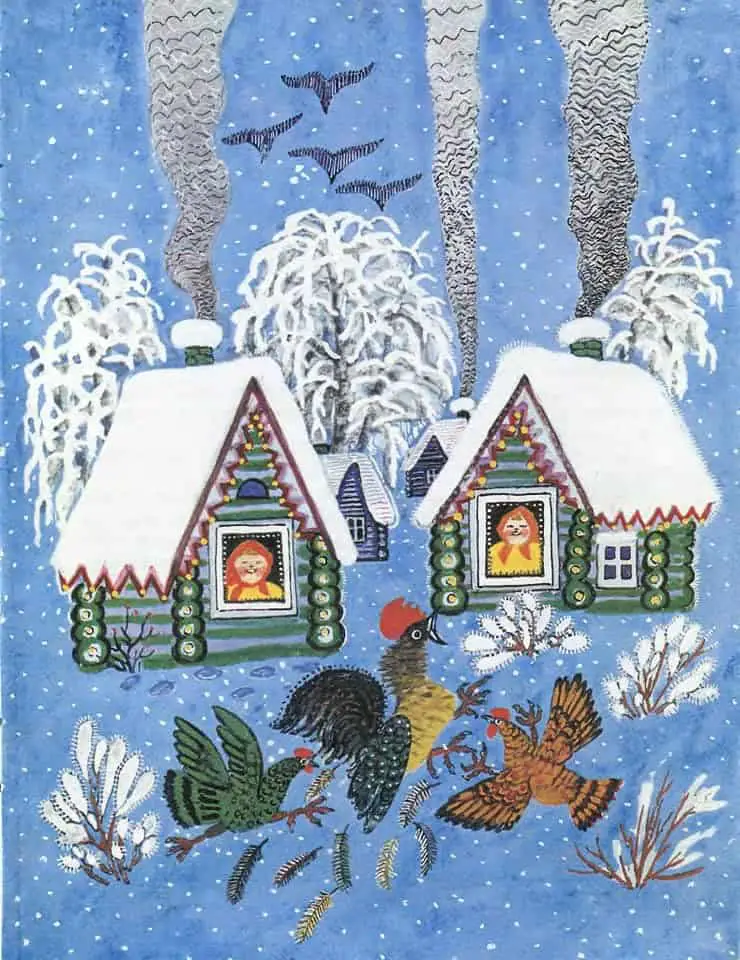

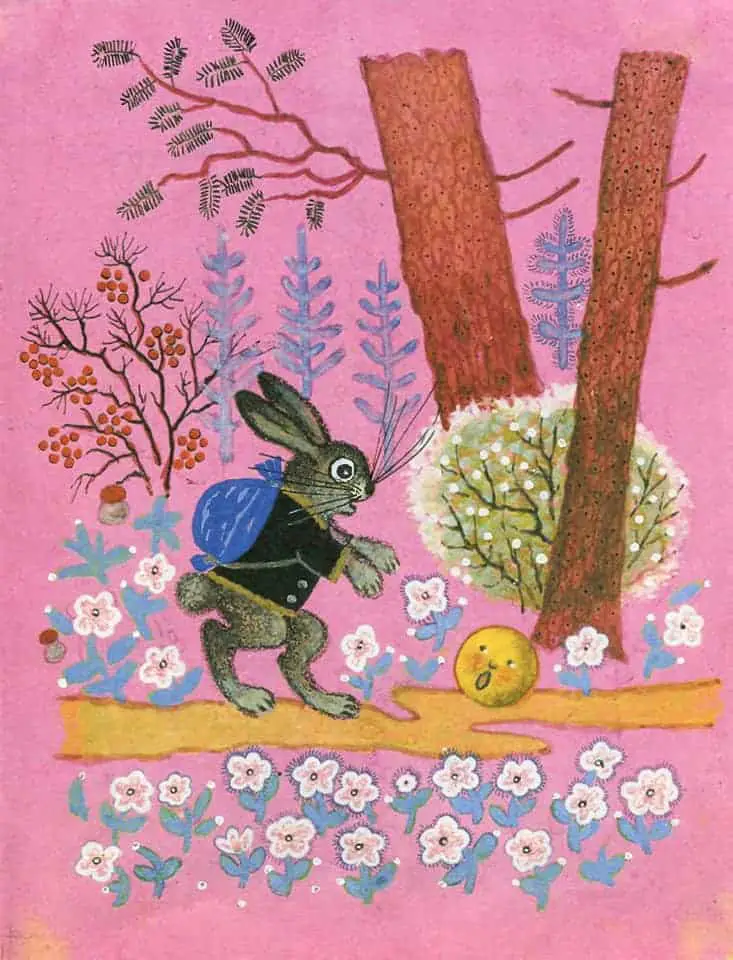

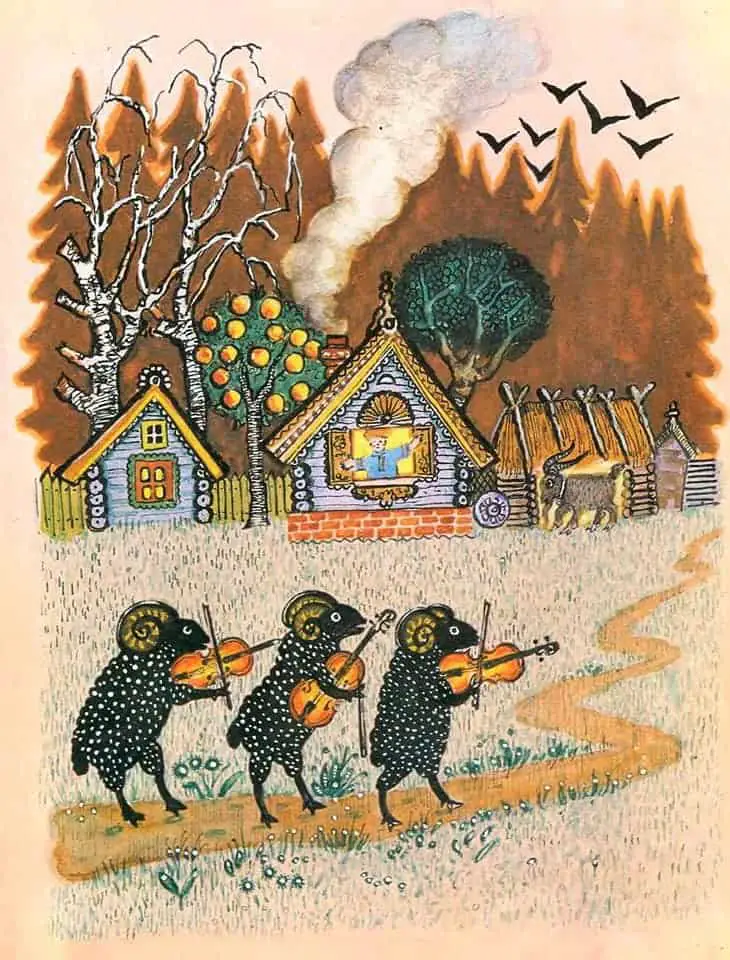

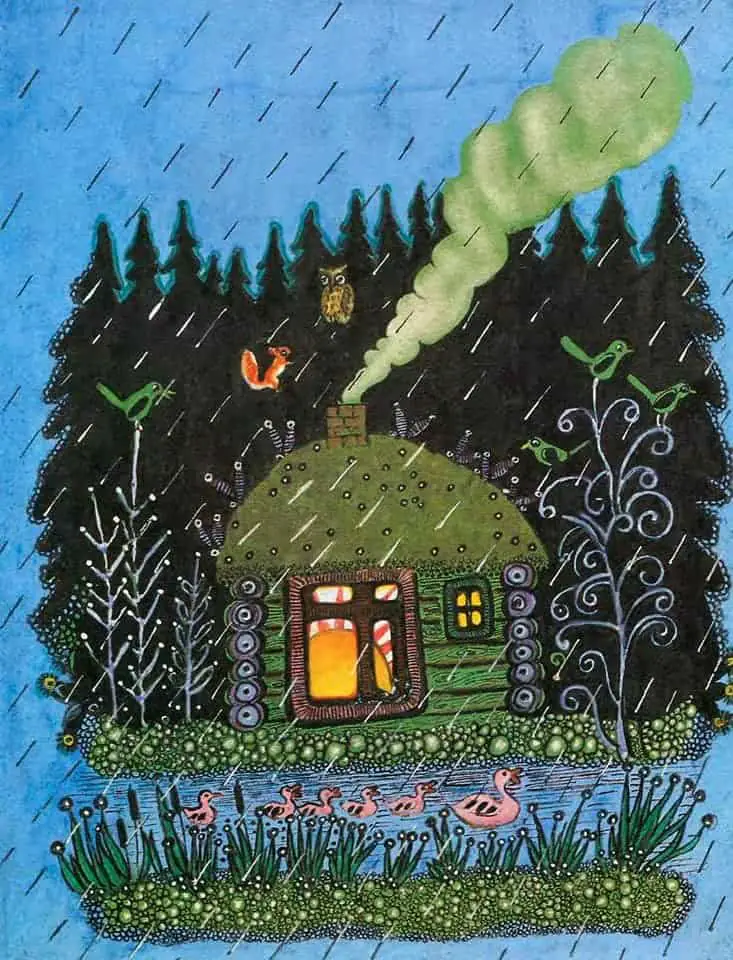

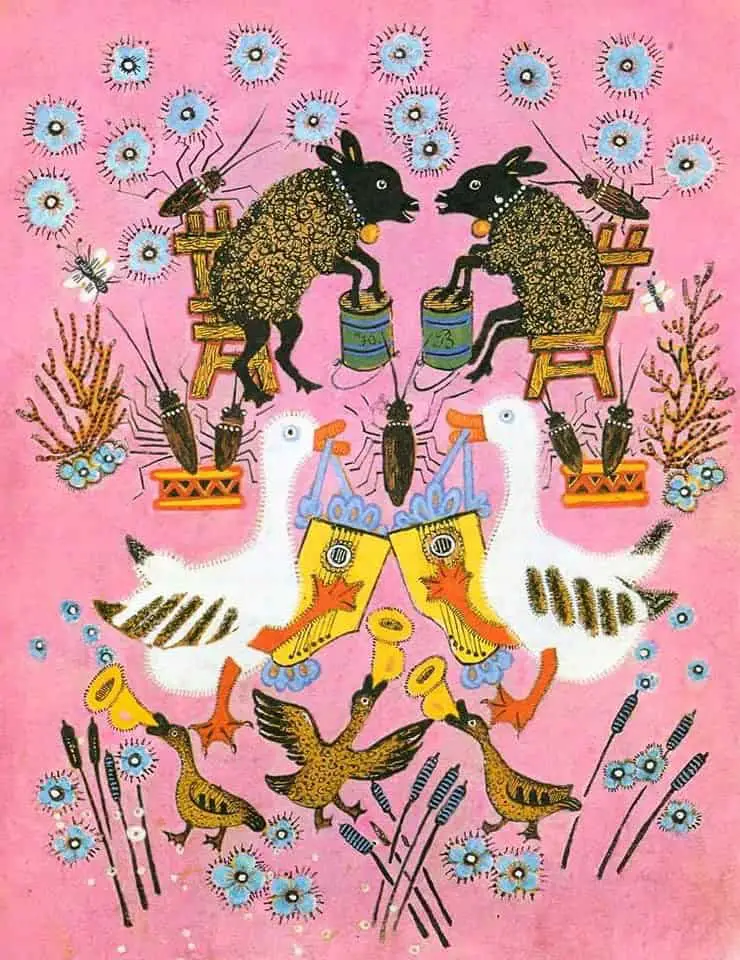

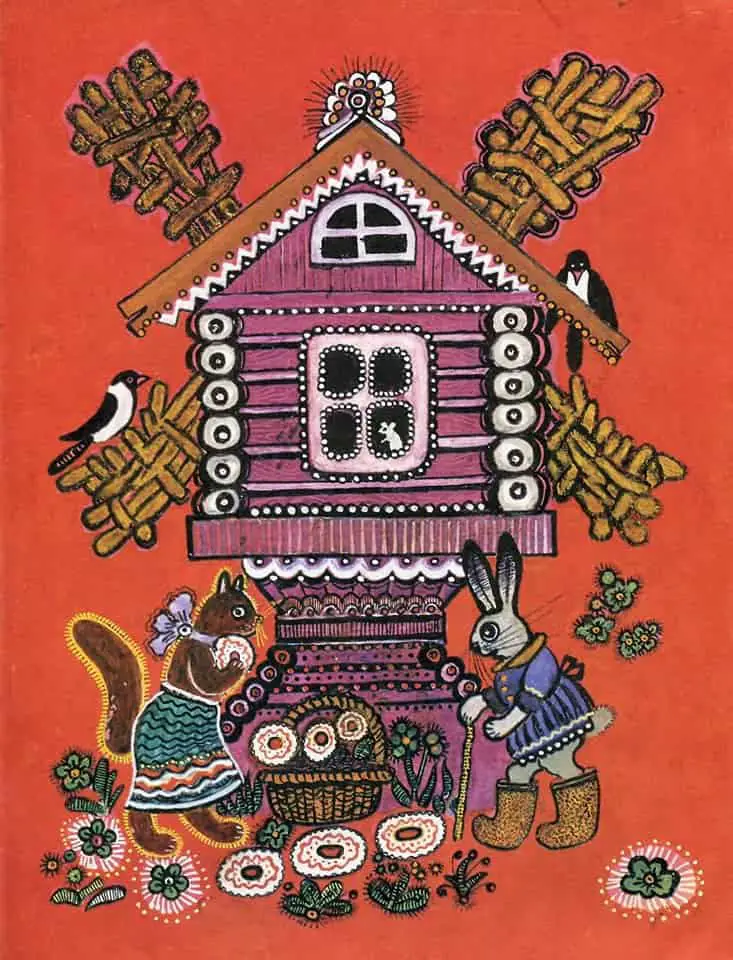

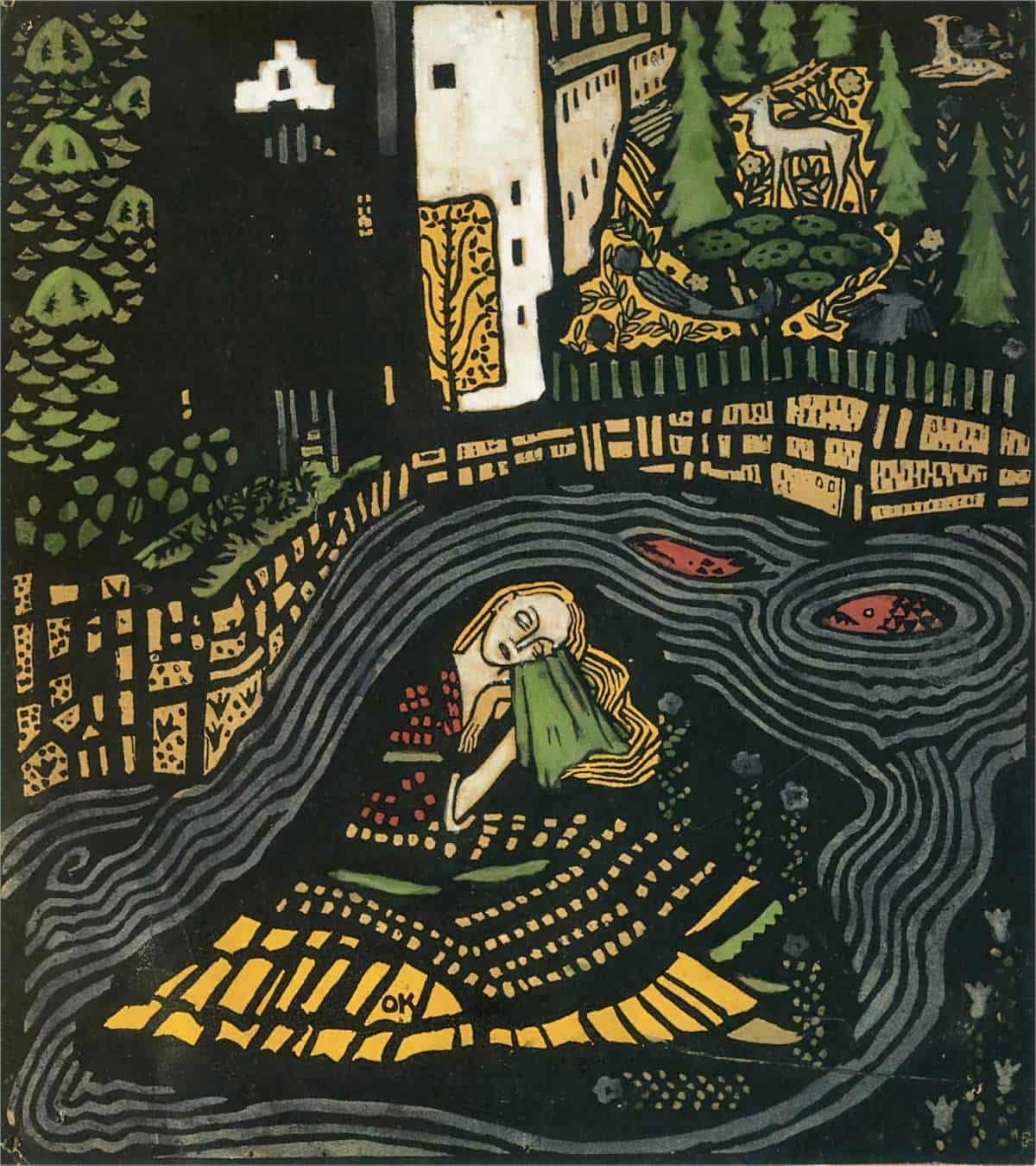

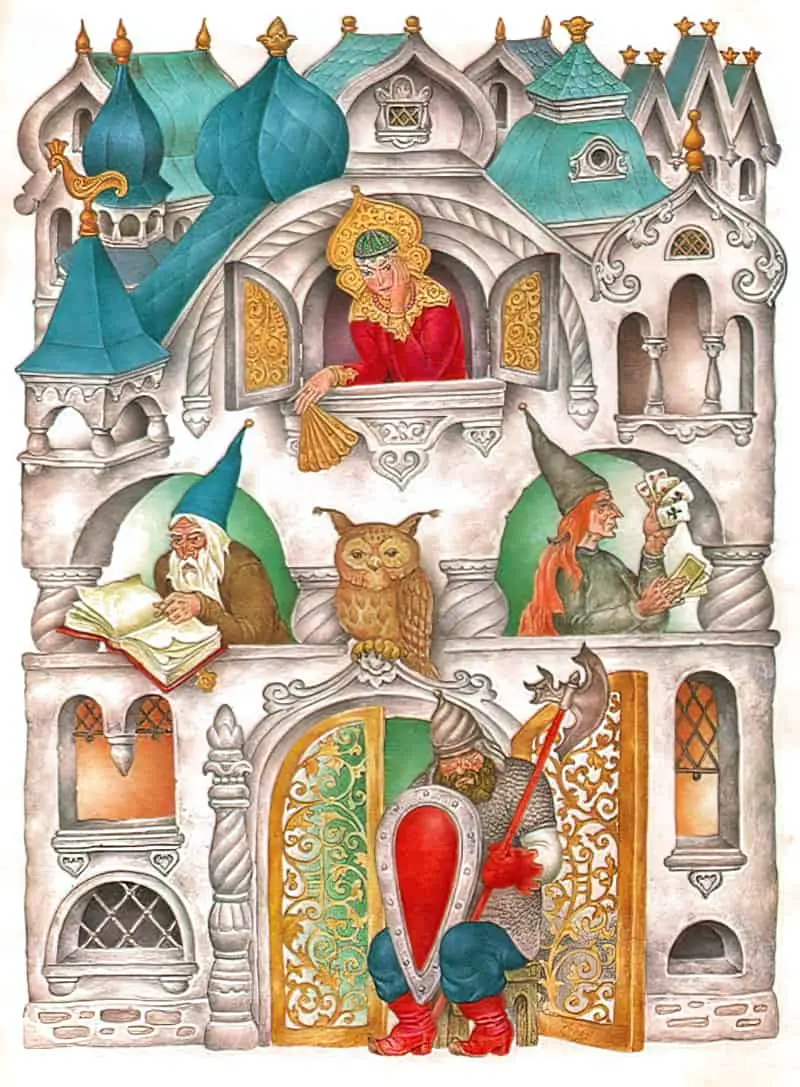

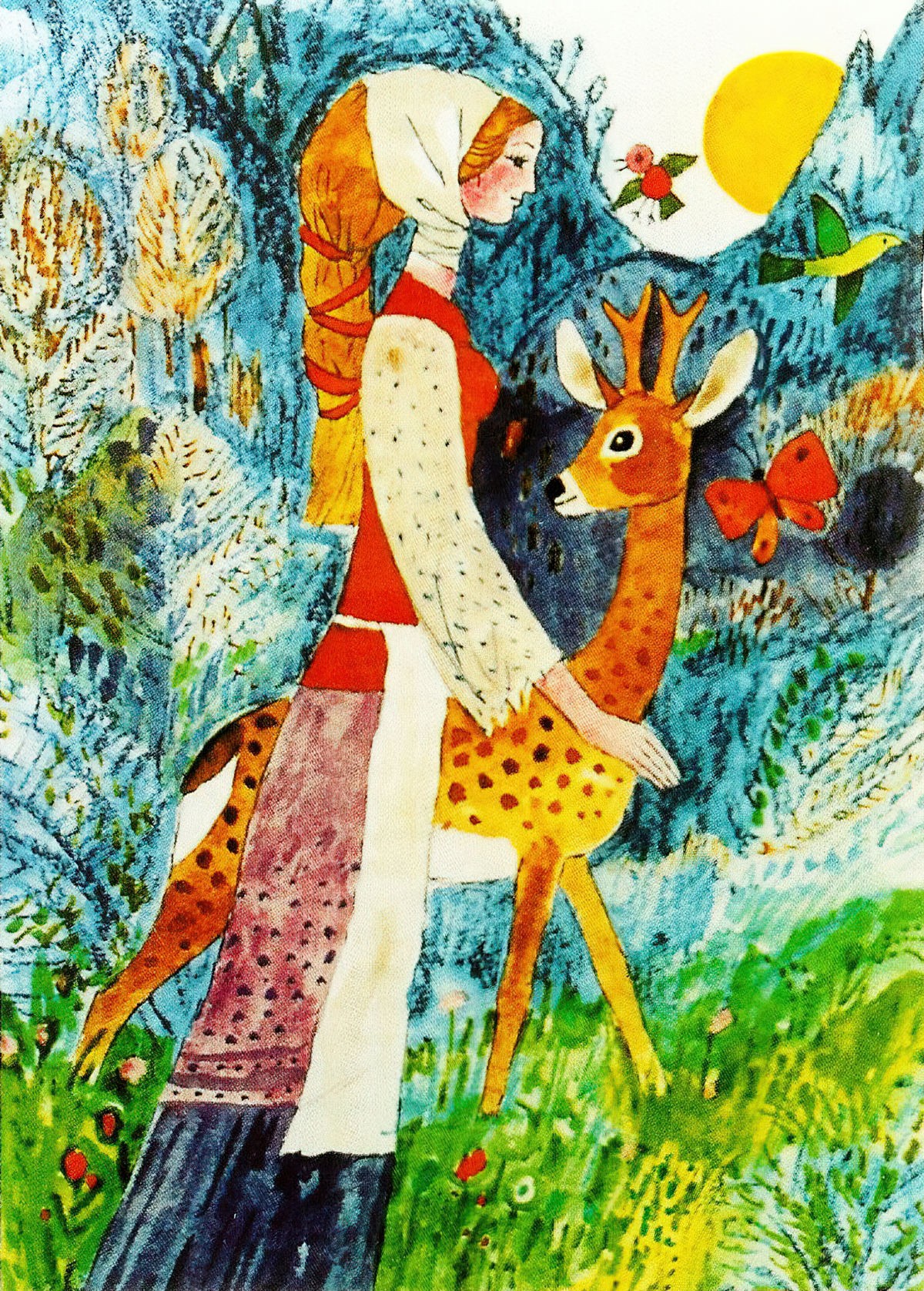

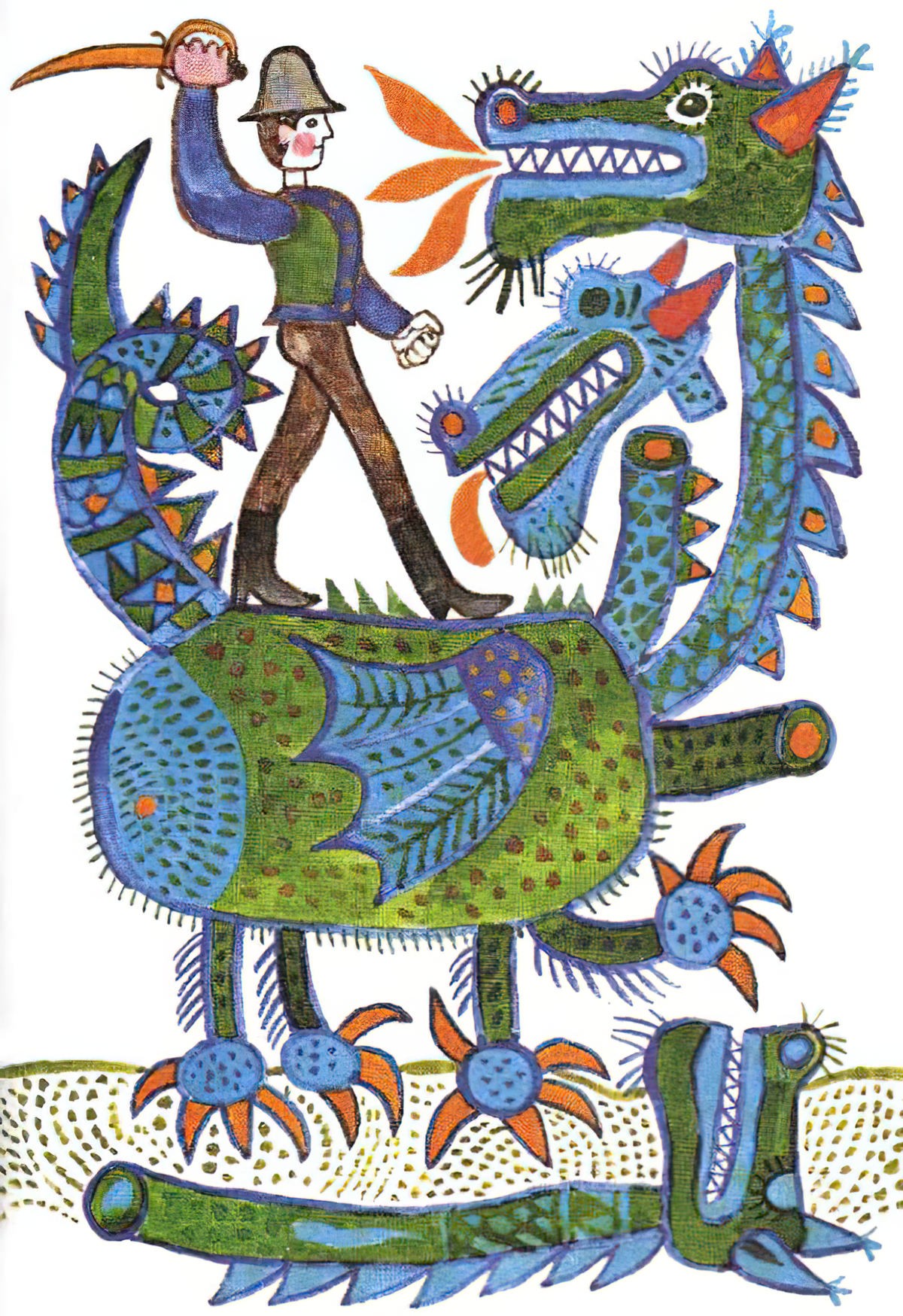

When it comes to choosing a colour palette, the more removed from reality, the more removed from realism. When illustrating a fairytale, the artist has complete freedom of colour.

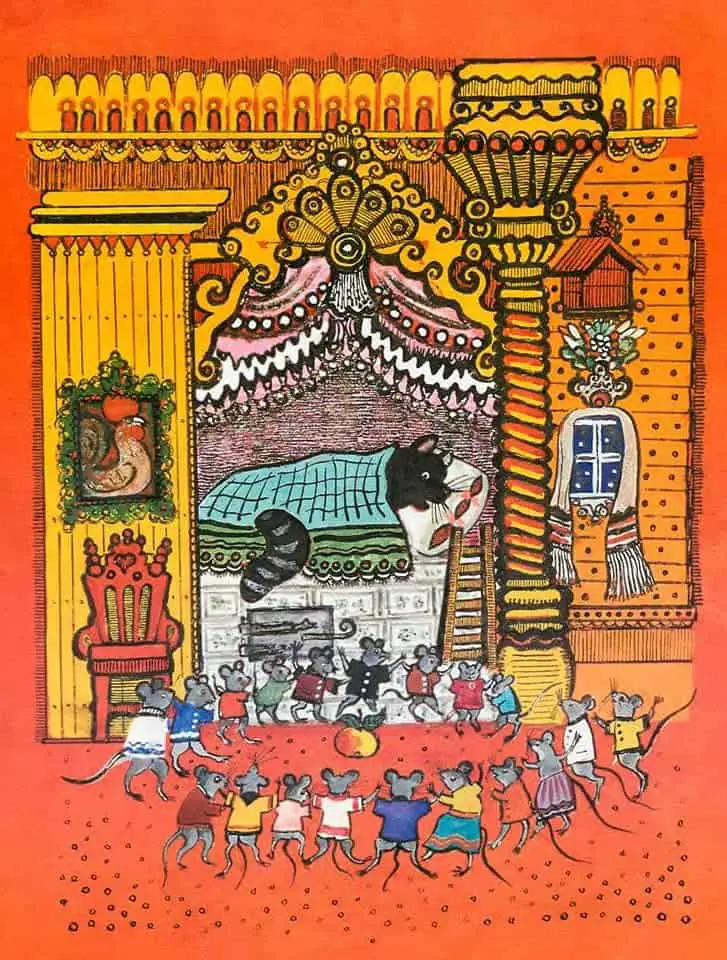

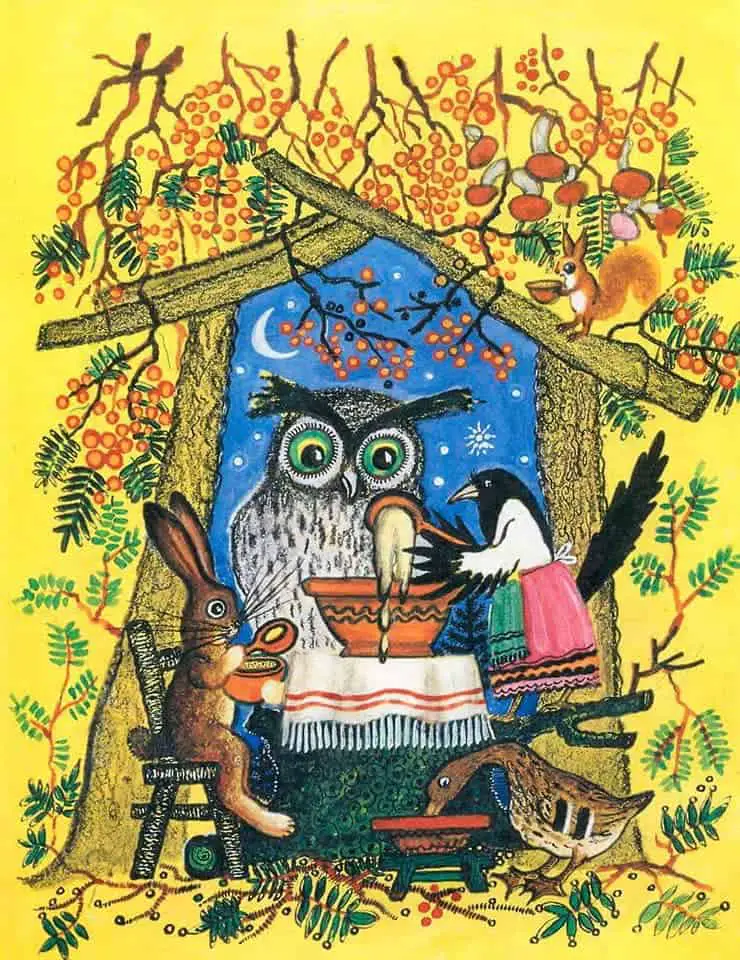

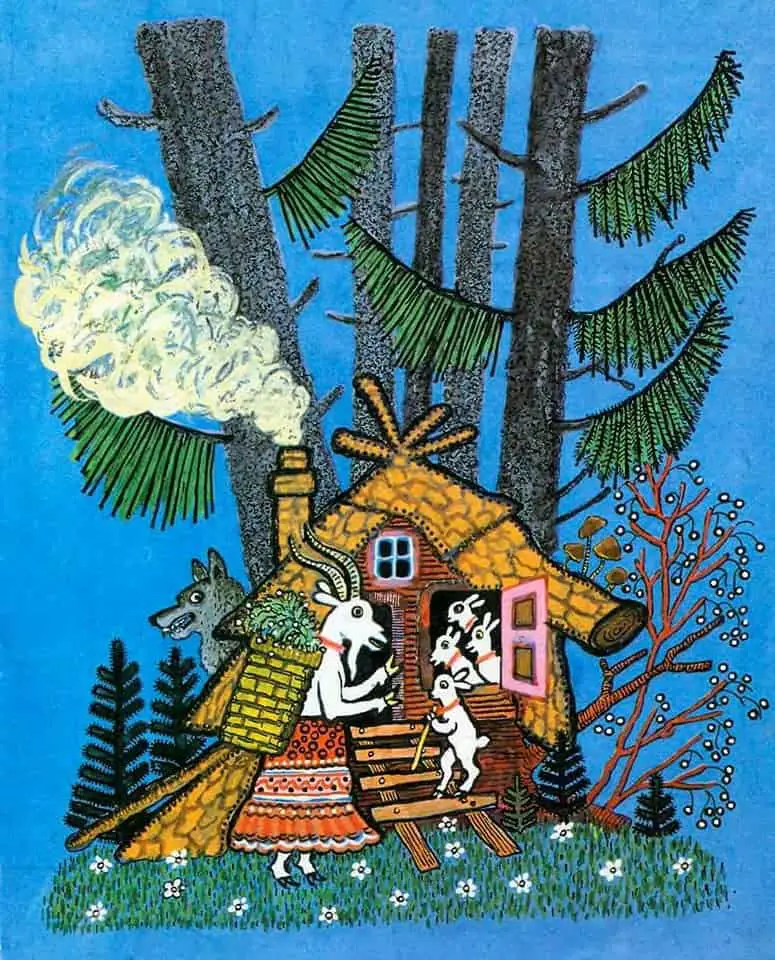

The illustrations below are by Yuri Alekseevich Vasnetsov for a book of Russian fairytales.

Fairytale Time

[Fairytale world is] a realm of events not present to the storytelling occasion at all but conjured up for the occasion by the story.

Katharine Galloway Young (1987) (211)

Once upon a time…

Fairy tales [use] well-recognized framing formulae like “once upon a time” to open and “and they lived happily ever after” to close. Openings can be simply “There was once” while closings tend to be more diverse, including:

- They remained happy and content/While we still don’t have a cent

- They remained rich and consoled, and we’re just sitting here and getting old”

- And those who tell this tale and whoever caused it to be told/Will not die a terrible death whenever they grow old.

Fairytales are separate from linear time. They take place in some parallel world, like a non-mechanical Steampunk world, in which had things panned out differently we might still be living there. Grimm fairytales are low on detail, but we know they’re not set in the here-and-now.

In Greek there are useful words which draw a distinction between linear, realworld time and eternal, mythic time: chronos and kairos.

The snippet below is from a children’s book about a boy who takes an Arctic journey to connect with an ancient version of himself. In doing so, he enters a mythological world in which time operates as kairos, not chronos. This example offers some insight into why a chronos sense of time wasn’t all that helpful to an ancient hunter gatherer way of life:

“When the seal starts to come there is a scratching sound and the hunter must be ready to put the point in then.”

“How long must one wait?” Russel asked.

“There is not a time. Waiting for seals is not something you measure. You get a seal, that is all. Some men go a whole winter and get none, some will get one right away. Hunting seals with the small point and the killing lance is part of the way to live.”

Dogsong by Gary Paulsen, p52

Time in dreams is frozen. You can never get away from where you’ve been.

Margaret Atwood

Fairytales take place in the primordial time of kairos. The Latin term for kairos is in illo tempore.

- Unlike chronos, kairos is reversible and ‘returnable’.

- Kairos is not entirely separated from chronos. We ordinary folks can integrate linear and mythic time by performing rituals, which are timeless because they are repeated linear season after linear season. Rituals, rites, festivals and carnivals serve the purpose of rising above linear time.

- Carnivalesque stories start in chronos, switch to kairos then return the main character back to chronos.

- Until about the age of five, children live entirely in the present, unable to conceive of linear time. Children’s stories are therefore well-suited to fairytale notions of time. They share this in common with archaic humans, who did not live by the modern clock.

- It is interesting to look at a story in terms of ‘iterative frequency’. For more on that see Iterative and Singulative Time In Children’s Literature. In singulative time, events take place once. In iterative time, events take place time and time again. Kairos is more pagan, because rituals and events take place seasonally, year after year, making them iterative. Archaic gods returned time after time. Christianity is more associated with chronos because Jesus dying on the cross was a one-time event. In this way, kairos becomes associated with those stories from antiquity. Recorded history is iterative, in which each event is considered to happen just the one time.

Fairytale Seasons

Compared to here in Australia, Europe is dark. I think of a time between seasons. When Hans Christian Andersen wrote his literary fairytale The Little Match Girl it was winter, and the ground was probably covered in snow, but Grimm fairytales seem set in some temperate time, somewhere between autumn and spring. Puss In Boots involves jumping into a river, so I imagine summer. The Frog Princess is frolicking around near a well, probably sitting on the ground, which is probably not damp. Again, probably summer, or midday in spring.

Time Of Day

It’s surprising to me how many fairytales take place during daylight hours. Or perhaps we simply assume daylight because the time of day is not mentioned. When the youngest son sets out to ‘seek his fortune’, we assume he sets off in the morning. Illustrators do, too. It’s a fair assumption. People in earlier times truly believed that night-time was dangerous in itself, for its noisome vapours. That’s over and above wolves and burglars and what-have-you.

Fairytale Geography

When Arthur, Ren and Cecily investigate a mysterious explosion on their way to school, they find themselves trapped aboard The Principia – a scientific research ship sailing through hazardous waters, captained by one Isaac Newton.

Lost in the year 2473 in the Wonderscape, an epic in-reality adventure game, they must call on the help of some unlikely historical heroes, to play their way home before time runs out.

Jumanji meets Ready Player One in this fast-paced adventure featuring incredible real-life heroes, from the internationally bestselling author of The Uncommoners series.

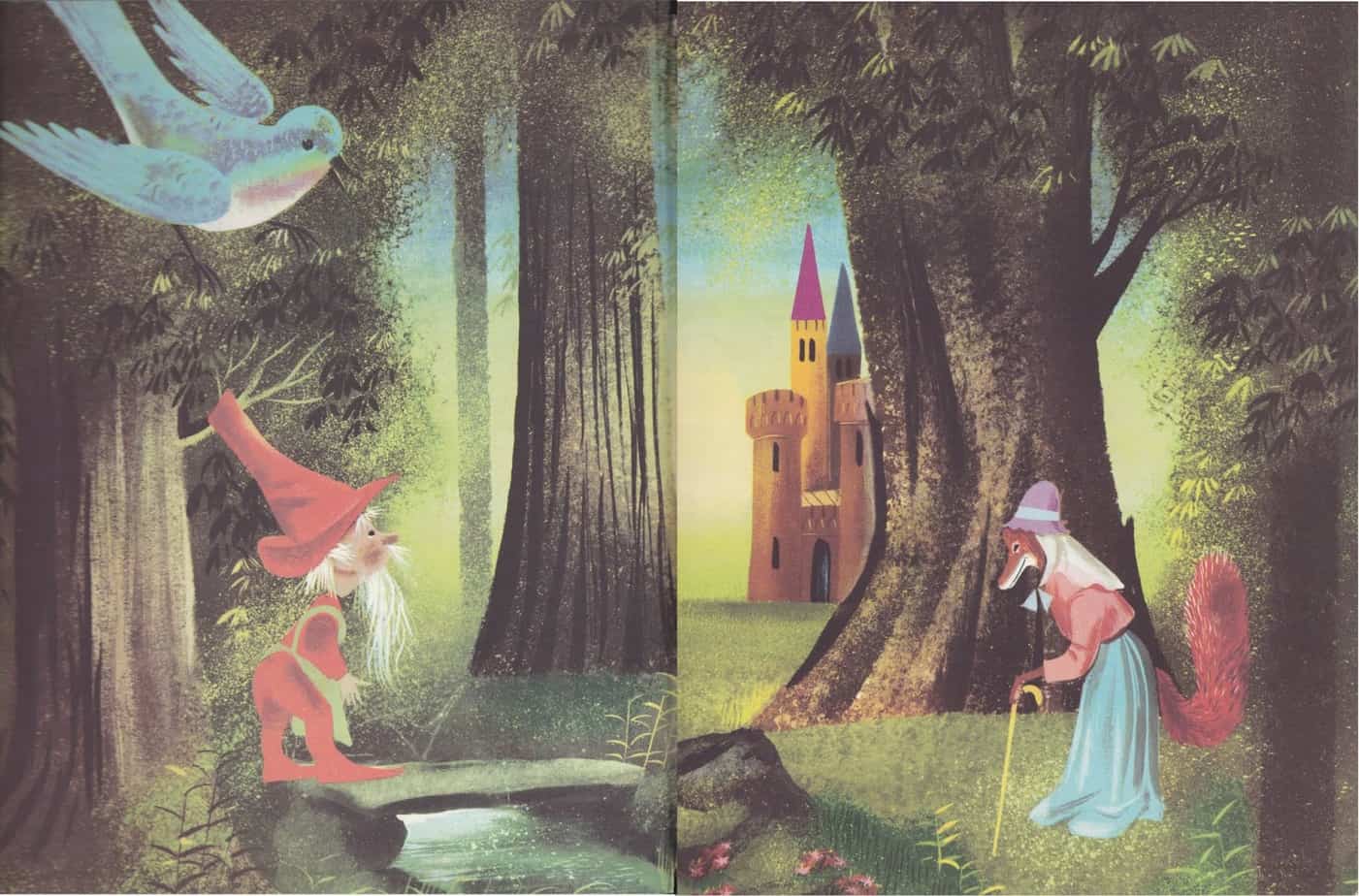

The fairytale world is an outworking of the subconscious. When characters enter the forest, they are delving into the deepest, most scary parts of their minds, facing their deepest, darkest fears.

When they walk along a path, or float down a river, they are embarking upon a mythic journey.

When they go underground they are dangerously close to the evils of hell.

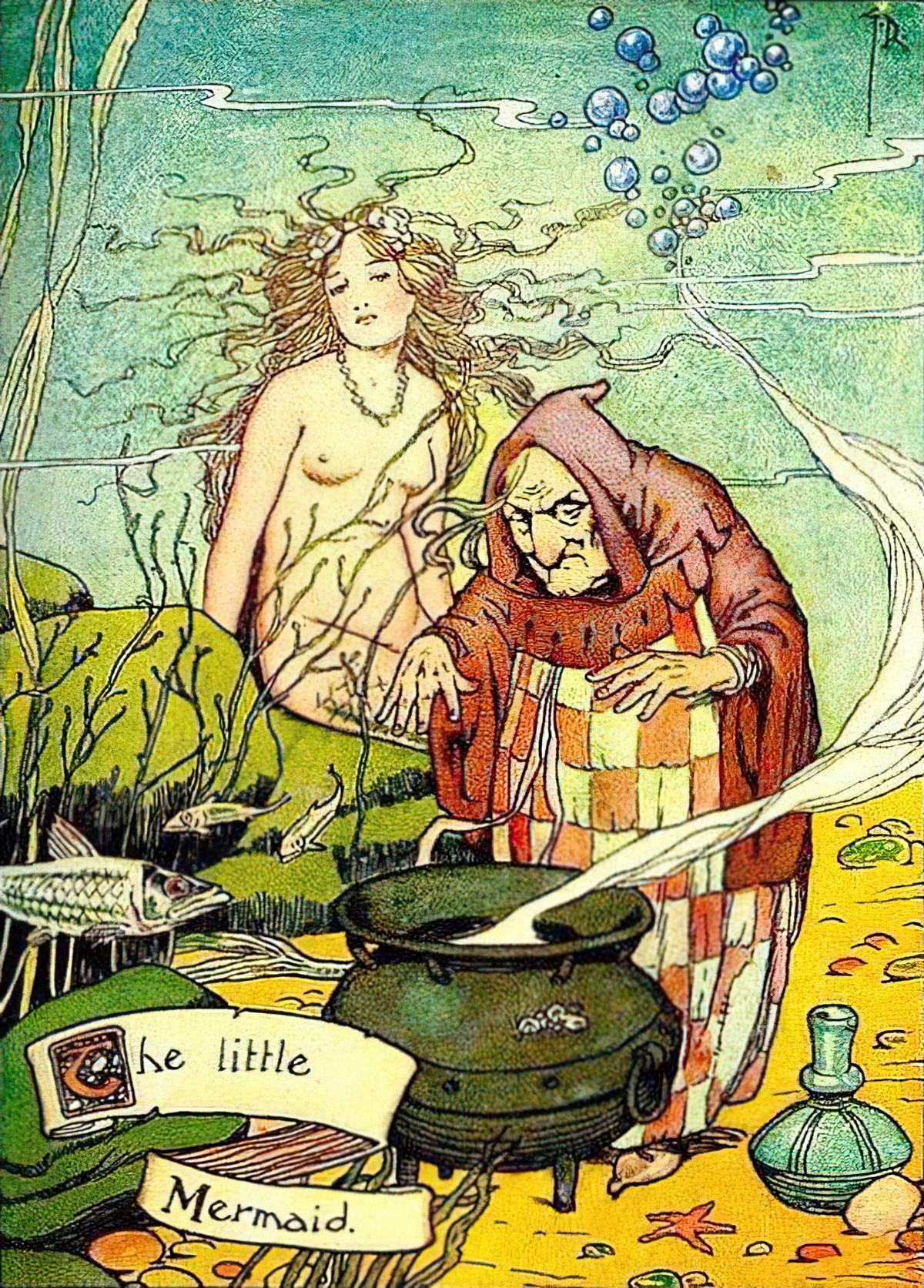

When they venture under the sea, they are taken to another subconscious place, reminiscent of existing in utero.

Fairytale Health

Blindness is temporary, and therefore probably metaphorical.

SLEEPING HERO MOTIF: A motif common in Celtic folklore and Arthurian literature in which the heroes or mythological beings of old are not dead, but rather sleeping, waiting in heaven, or stored in alternative worlds like Fairyland. At some future time, they will awake or be called forth to fulfill some important function. In the legends of King Arthur, for instance, Malory recounts him as “Rex quandam et rex futurus,” the once and future king who will return to Britain in the hour of its greatest need. We see 20th-century versions of this recreated in C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia. For instance, in Prince Caspian, Caspian’s forces re-summon High King Peter and the other Pevensie children to save them from the Telmarine usurpers. More apocalyptically, in The Last Battle, we read of how a giant named Time sleeps in a cavern under the earth, waiting for Aslan to wake him so he can blow his horn to summon the stars from the sky before he plucks the sun of Narnia and destroys the world. Anthropologists might argue that, in the Christian tradition, the idea that Christ will have a second coming and return to earth is another example of the motif.

Literary Terms and Definitions

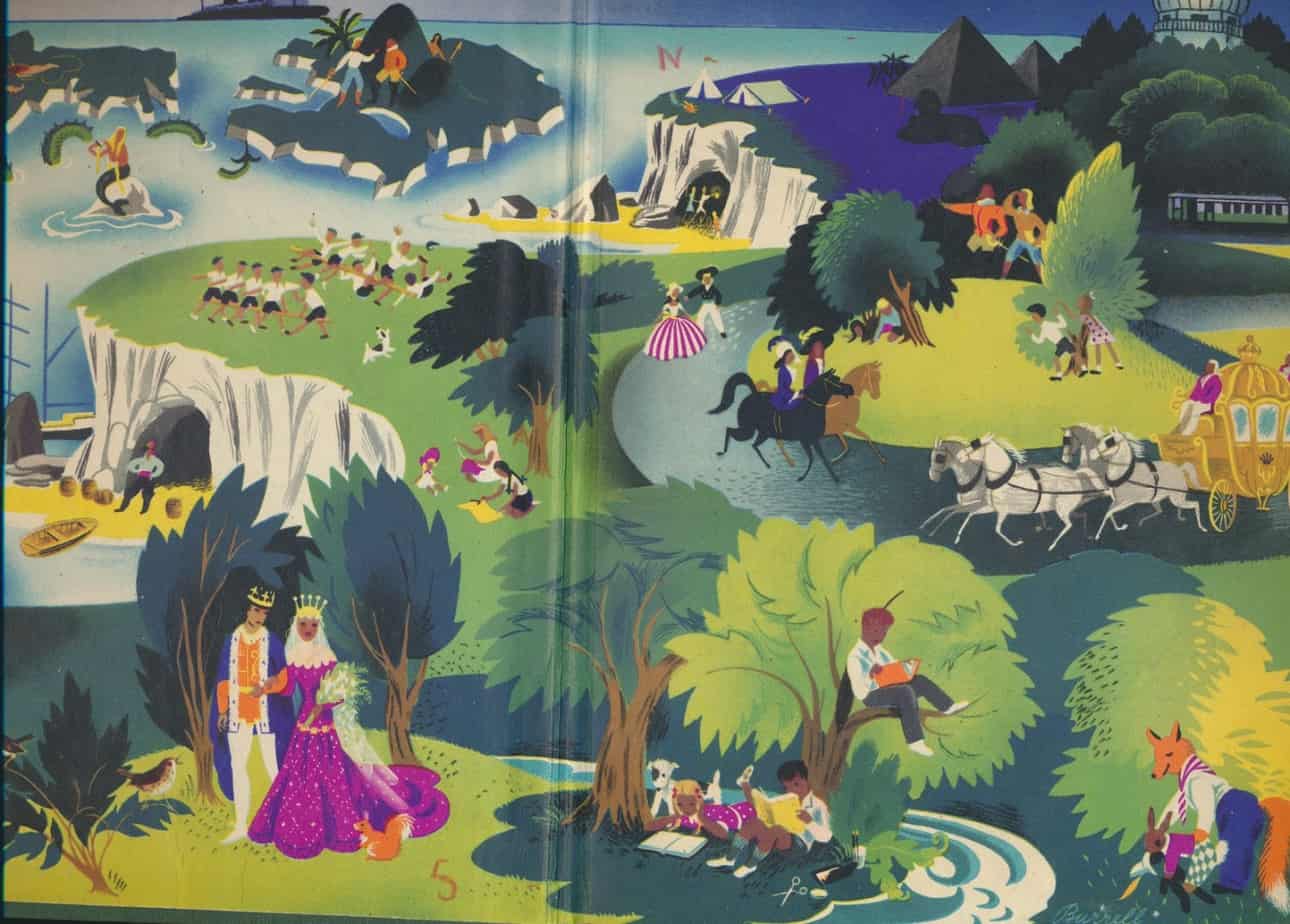

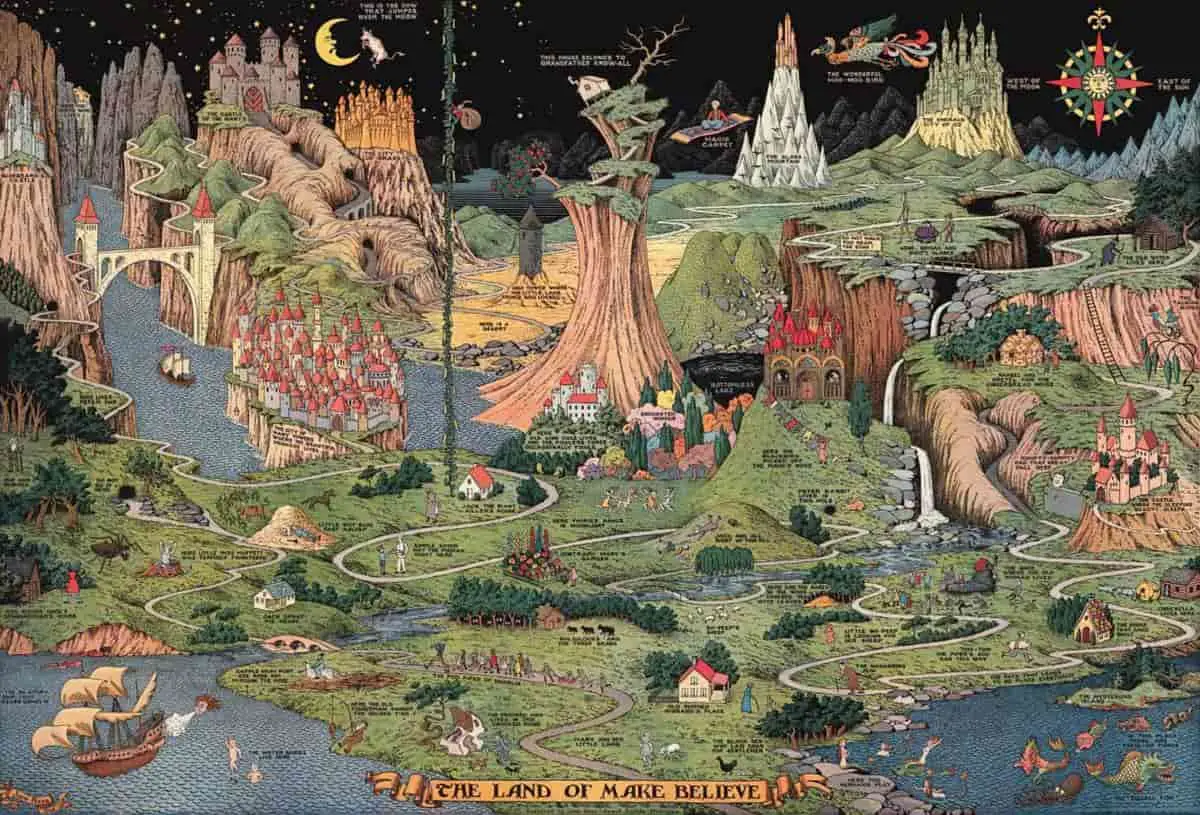

“The Land Of Make Believe” was created in 1930 and exhibited in the children’s section of Chicago’s 1933 Century of Progress World Exhibition. Illustrator Jaro Hess originally sold copies and the map himself. The poster found its way into classrooms and children’s bedrooms across America. Many American adults today recognise the map from their childhood.

The art style looks influenced by Hieronymus Bosch (for example The Garden Of Earthly Delights). Bosch was born in the mid 1400s.

In Hess’s ilustration, over 30 fairy tales and nursery rhymes appear on a fantasy map. Some are better known than others:

- “The Pied Piper of Hamelin“

- “Goldilocks and the Three Bears“

- “Jack and Beanstalk”

- “The Wandering Jews“

- “The Wonderful Moo-moo Bird“

- “Skull Fish“

Desperate Housewives has a fairytale vibe, and because fairytales have been read by children since the era of the Grimms, fairytales put an audience in mind of storybooks for children. There is plenty Desperate Housewives shares in common with children’s books:

- The utopian facade, though in a children’s book the utopia is often a genuine idyll. Desperate Housewives is filmed on a set, not on a real street so absolutely everything we see on Wisteria Lane is ‘fake’, as well as carefully planted there. The creators describe Wisteria Lane as ‘hyper-real’.

- The calm, all-knowing narrator, explaining truisms to the audience in a soothing, before-bed kind of way

- The structure of the stories, which are bookended in a way many children’s books are, as well as smaller things such as switching from iterative to singulative time.

- Though it’s not a strictly followed rule, episodes tend to open in the morning and are drawing to a close once we start to see conversations at bedtime, even if the episode itself spans several days. Many picture books work on a 12 hour clock, starting with the child getting out of bed, ending with them back in bed and ready for sleep.

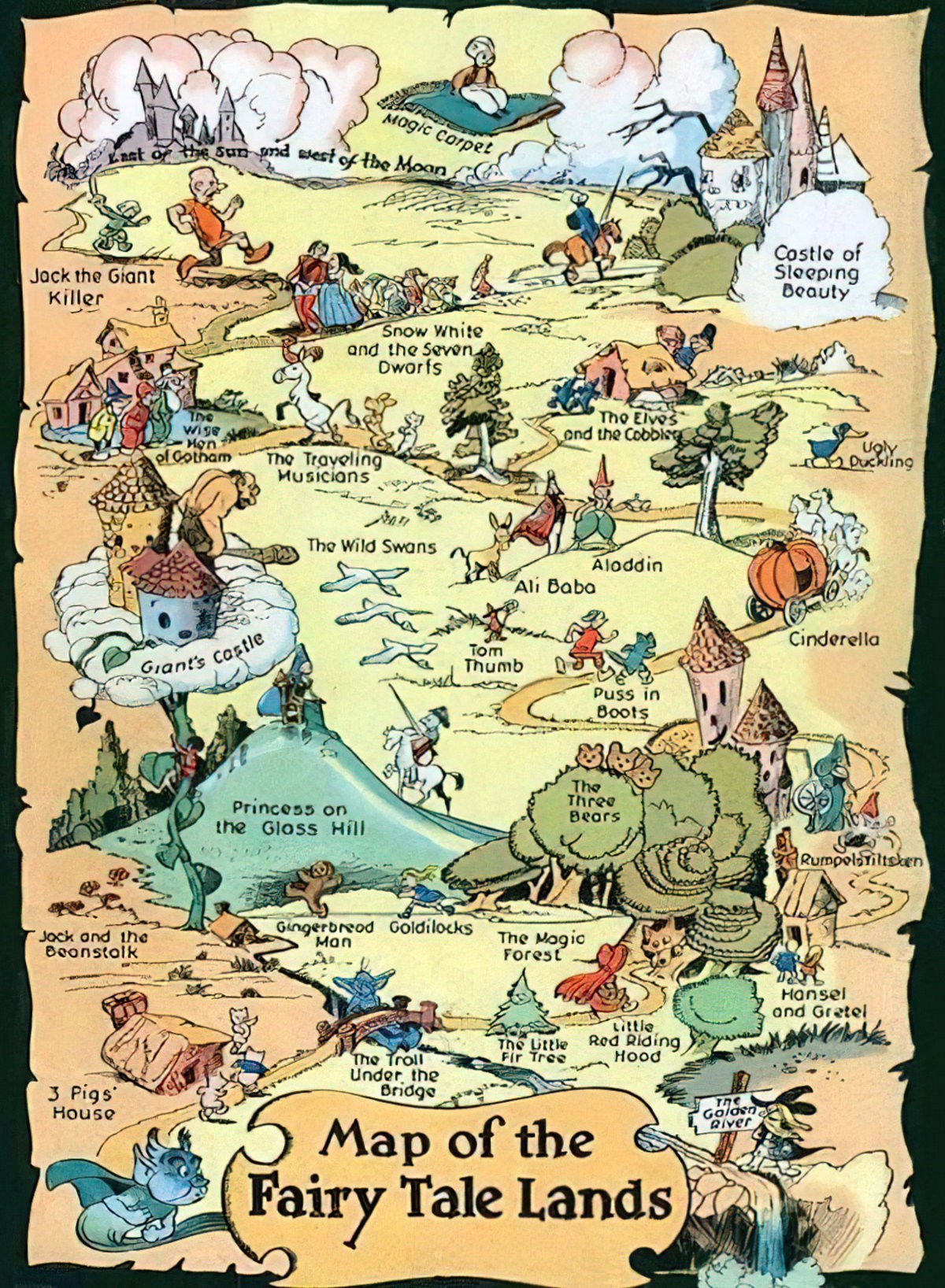

Fairytale Features Of The Land of Make Believe

- The land stretches out in all directions, with kingdoms separated as if by bubbles. We hear a lot about royalty and relatively little about the peasants. There are too many chiefs and not enough Indians in these fairytale worlds. More stories have always been told about the rich and powerful. These lands must therefore be peopled by the invisible. We see extraordinary peasants in fairytales. But we don’t see permanently ordinary people in the fairytale landscapes of our imaginations, except occasionally as the Simple Simons, who we meet on the roads.

- The world stretches vertically, both under the ground and into the sky, somewhere between Hell and Heaven. There are underground caverns full of treasures, and ogres can live in the sky counting their fortunes.

- Currency is in precious metals but also in magical items. Magical items tend to be everyday items with magic imbued, like beans or broomsticks. This is fairytale technology. Seven league boots and magic carpets are the high speed rail and aircraft of fairy land.

- There aren’t actually many fairies, depending on what you mean by fairies. If you’re thinking of Tinkerbell archetypes, those are a recent iteration. In a wider conception of the term, a fairy is any sort of imagined-up creature and they populate every imaginable space, because humans abhor a vacuum.

- Size trumps smallness, but size and smarts are negative correlated. Small tricksters will win over big oafs.

- There’s no police force. You’re on your own. There is, however, vigilante policing of other people’s behaviour, and notions of fairness involve retributive justice. People who are underdog tricksters are exempt, and may take any amount of power for themselves. Beautiful young women are also exempt.

- Old women are feared as the personification of death. We call them witches.

- As in a dream, characters can transmogrify. Witches can seem like beautiful women and vice versa. Even a house can appear as something it is not, exemplified by the gingerbread house of Hansel and Gretel.

- Glass technology is really quite old, but sheet glass took a lot longer to craft. Humans have long been fascinated by glass — in fairytale world glass (and the mirror) is as fascinating as fire for its ability to change form.

Fairytale Settings Are Allegories Of Common Fears

Fairytales are allegories — extreme metaphors — into the subconscious. The settings and characters serve that one, main purpose: To bring us into contact with our unvoiced, unacknowledged fears.

- The Frog Princess is about feminine The Fear of Engulfment (fear of pregnancy and childbirth)

- Jack and the Beanstalk is about the masculine fear of a remaining attached to one’s mother, unable to find independence.

- Rapunzel is about society’s fear of letting young women control their own sexuality, and is an outworking of our desire to keep them locked away, protected from the world. For young women themselves, it may function as a wish-fulfilment fantasy, to remain safe when the world outside seems so dangerous.

So if a story works allegorically and if you can easily pinpoint a specific universal fear, the story is fairytale-esque.

Muted Character Desire

Fairytales rely on character archetypes, and one way to create a unique character is to give them unique goals and wishes. But in a fairytale, everyone wants gold and everyone wants a baby. In fairytale world, this is assumed fact. The more muted the characters’ desires, the more they ‘sink into’ their worlds, riding on the wave of whatever comes their way, the more ‘fairytale’ a story will seem to the reader.

Not all fairy tales are influenced by the Romance era, but in the Romantic tradition, character desire doesn’t seem to be as vital to story as mood and symbolism. Romantic poets did not aspire to create active participants in the stories. They were more about tortured souls. Their heroes and heroines were the original Goths, haunted by poetry, at the whims of strong forces, often supernatural, outside their control and understanding. If the main characters can neither control nor understand their worlds, then this is a fairytale world.

Fairytale Narration

Even back in 1988, Linda Hutcheon said that contemporary readers were no longer accepting a truly omniscient, omnipresent narrator. Replacing that older style of narration, is a ‘dialogue between a narrative voice…and a projected reader’.

Nothing has changed since then. Close third person narrative is now the norm. How does this relate to the world of a story? It’s about chaos versus structure.

Classic fairytale narrators create an orderly and structured world, where everything happens for a reason in a predictable cause-and-effect chain. This includes retributive justice, “an eye for an eye”. Good things come to good people.

In contrast, the narrators of modern stories create a kind of chaos, for example by suggesting unreliable narration, polyphony (various voices), multiple plots, open endings and so on. These are features of modern stories, not of fairytales. (Maria Nikolajeva writes about this in From Mythic to Linear: Time In Children’s Literature.)

In years to come—and Boq would live a long life—he would remember the rest of the summer as scented with the must of old books, when ancient script swam before his eyes.

Wicked by Gregory Maguire

When the narrator skips forward as in the example from Wicked, above, readers get the strong sense of a story set in the distant past, which generally has the effect of making it sound like a fairytale. (It’s done in A Series Of Unfortunate Events, too.)

Thematic Contrast

In the short introduction to Norwegian painter Theodor Kittelsen below, the narrator describes the thematic contrast Kittelsen created: The beauty of Norwegian nature against the horror of Norwegian folklore.

It’s not just Kittelsen: Illustrators of fairytales almost always create a beautiful world to juxtapose against the horror of fairytales. There are a few exceptions, but these stand out. One example of a non-beautiful fairytale world is the Hansel and Gretel retelling by Neil Gaiman, illustrated in scary black and white by Lorenzo Mattotti.

Fairytale Logic

The rules of physics do not apply in a fairytale.

You can cover large distances in your Seven League Boots.

You can get eaten by a larger/fiercer creature, remain completely unchewed and undigested, and fight your way back out of its stomach, good as gold.

Then again, real life can be stranger than fairytale.

Case Study: Into The Forest

Into The Forest is a thriller film ostensibly set in a modern day, dystopian world, attracting an audience who expected modern day logic. But the ending to this story made clear that this is in fact a world which runs on fairy tale logic. Two sisters burn down their family home and retreat into the woods to live in the wild, along with a new baby. They are to survive on nuts and berries, we assume. This is a frustrating ending for audiences expecting a different genre, because according to real world logic the young women have made a deadly mistake. How to survive without shelter?

This is frustrating for an audience. Surely they would’ve been better off staying in their house and fixing it to a liveable standard.

But if we apply fairytale logic, the ending makes sense: They can no longer stay in their natal home because the memories of it are metaphorically infecting their present reality. They therefore have no choice but to retreat into the woods, where it is always possible to support oneself in the cathedral of trees, eating seasonally and abundantly, at one with nature, as fairytale girls are sometimes able to do.

The Fear of Engulfment (due to pregnancy and danger of childbirth) is a strong thread in Into The Forest.

Consider the ending of Into The Forest alongside this passage from The Sundial by Shirley Jackson:

It has seemed to me that this house will become a kind of shrine, for our children,

The Sundial, Shirley Jackson

and for their children. Living in the fields and woods as they do, living under a

kindly sun and a gentle moon, with all their wants supplied from nature, they will

have no thought of houses, and a roof will become to them synonymous with an

altar; we may yet live to see our grandchildren worshipping in this house.

RELATED

Ringlorn: adj. the wish that the modern world felt as epic as the one depicted in old stories and folktales.