Have you ever lived in close quarters with strangers? Perhaps you went out of your way not to know these people, but in the name of etiquette rather than aloofness. There’s something discomfiting about living in a stranger’s pocket. Like commuters on a packed train, we avoid each other’s gaze.

Failure to know our neighbours is said to be a modern ailment. “In the olden days communities were stronger!” we hear, as evidence of modern societal breakdown. But was that ever true of the cities?

Whenever humans are forced to live in close proximity a tacit rule plays out: we pretend to be less proximal than we really are. Desmond Morris wrote about this in The Human Zoo (1969). In cities, we think of other people as trees. There’s no way we can stop and say hello to everyone. We walk right past fellow humans. Yet if we were in the forest and saw another human for the first time in days, we’d stop and have a conversation.

This rule of ‘polite ignoring’ has been in play ever since humans have lived in close proximity. Try walking through a city and saying hello to everyone. People will assume you’re not right in the head.

This rule applies to our neighbours. The closer your neighbours, the more the rule applies. I bet it has always applied. In lieu of evidence from the Stone Age, today I offer evidence from the 1930s — a short story by Carson McCullers, born 1917: “Court in the West Eighties”.

SETTING OF “COURT IN THE WEST EIGHTIES”

- New York, 1930s, and as the title says — in the West Eighties. This is not a story that could have been told in my home country of New Zealand, say, because 1930s New Zealand didn’t have the population density of New York.

- The story begins in Spring — a time of new beginnings — and also warm enough to allow windows open. When the narrator says ‘I cannot understand why I was so unconscious of the way in which things began to change’ she is ostensibly talking about the changing of the seasons, but she is also describing her own gradual epiphanies about life and human nature. Epiphany is the wrong word, in fact, because an epiphany is sudden. There is no ‘epiphany’ here — more like a realisation akin to ‘the thing, sooty-gray patches of snow disappearing’. McCullers is using the seasons as a metaphor for the range of character change (not much, and slowly).

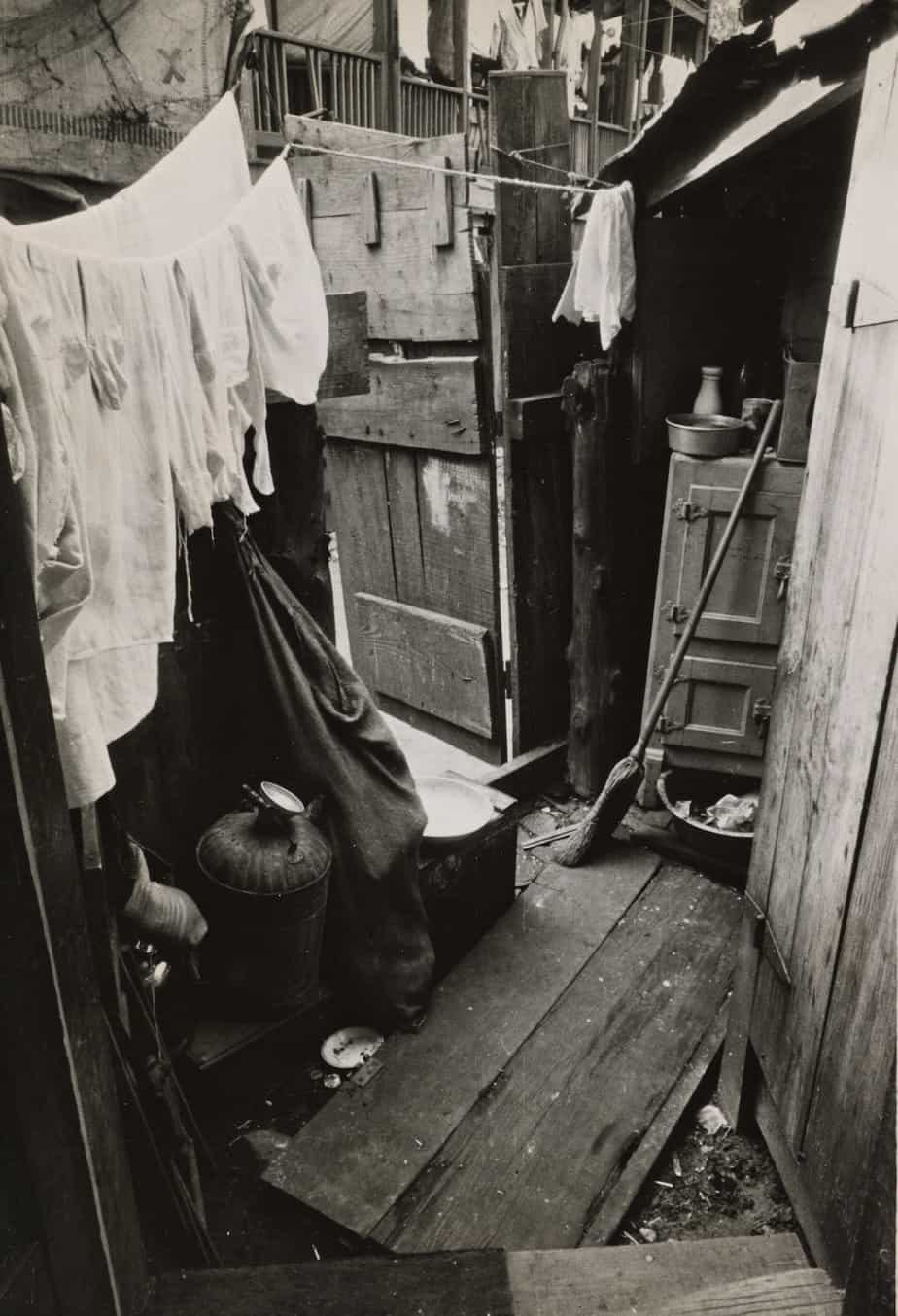

- The narrator is living in cheap housing as a student — ‘Four walls of little rooms’. In 2018 The New York Times made a time capsule which included 1930s New York. But I’m having a bit of trouble visualising exactly how the narrator’s court and rooms are laid out.

- The Great Depression was the worst economic downturn in the history of the industrialised world (so far), lasting from the stock market crash of 1929 to 1939. Though the depression is not mentioned directly, it is almost certainly the reason why the husband next door is out of work. McCullers makes sure to introduce economic woes early on by mentioning the friend back home who can’t go to university (despite being a natural academic) because his father is out of work. This was a time of mass unemployment. Adults who’d never experienced starvation as children went hungry for the first time — an historically unusual form of hunger, and one which comes on the back of entitlement. Frustrated entitlement leads to anger.

- The narrator’s eye functions as a floating camera. The ‘camera’ of the viewpoint narrator functions like a fish swimming through water. She can see details such as stockings in close up — enough to see that only the feet have been washed. She also sees her neighbours as long-shots, with full bodies included in the composition.

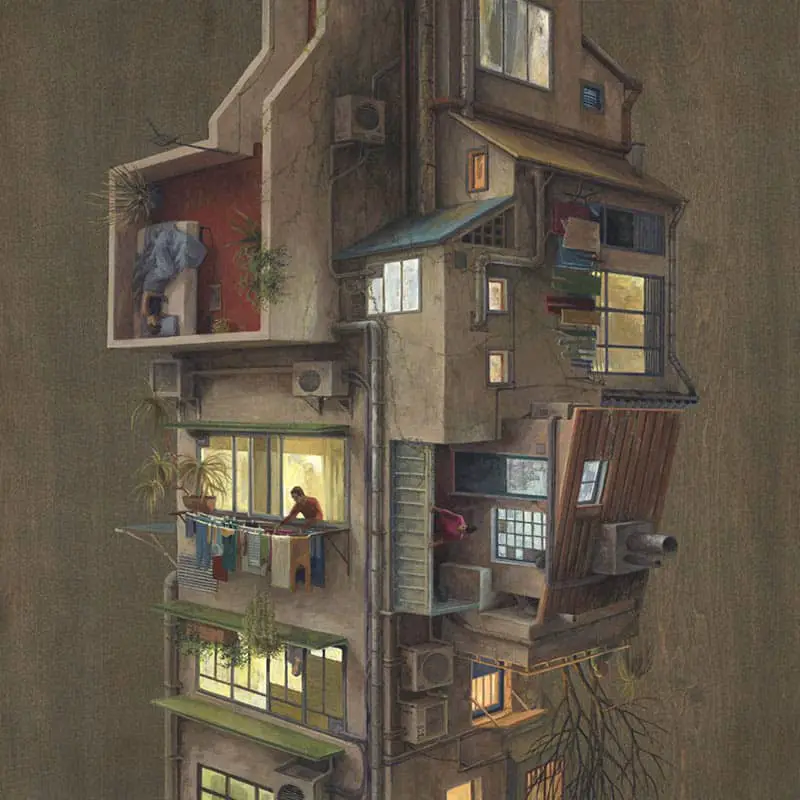

My spatial imagination thereby fails me. I end up imagining a dwelling like a painting by Cinta Vidal:

I’d like to find a photo which shows how the real apartments of the upper eighties would’ve been laid out. In the meantime, Vidal’s Escher-esque painting is actually pretty good as a metaphorical representation. As interpersonal dynamics play out, the narrator’s viewpoint shifts until she is no longer sure how the world works, or what happiness looks like for a woman.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “COURT IN THE WEST EIGHTIES”

This story is a good example of ‘main character subversion‘. The first paragraph leads us to expect a somewhat eventful story about the red-headed man, but as we eventually find out, there is no real story to this guy:

During all this time I can remember seeing only a few incomplete glimpses of this man living across from me — his red hair through the frosty window glass, his hand reaching out on the sill to bring in his food, a flash of his calm drowsy face as he looked out on the court. I paid no more attention to him than I did to any of the other dozen or so people in that building. I did not see anything unusual about him and had no idea that I would come to think of him as I did.

“Court in the West Eighties” by Carson McCullers

This subversion is helped along by the fact that, in the history of storytelling, red hair marks out a character as somehow special — a person things happen to. They stand out. But this man’s red hair is ironically without significance.

It would be interesting to know how Carson McCullers would identify if she were born 80 or 90 years later. Would she be gender expansive, gender non-binary, bi romantic ace? McCullers was certainly not an uncritical follower of the strict gender binary of her era. This short story serves as a critique of accepted feminine norms, about a narrator who, looking back on herself from a slightly removed distance, sees that she was naive about gender roles when she first came to New York.

SHORTCOMING

We are told directly of the narrator’s sex and age:

I have often thought that when you are an eighteen year old girl, and can’t fix it so you look any older than your age, it is harder to get work than at any other time.

Carson McCullers

The young narrator is developing ideas — or merely articulating preconceived notions — about femininity.

Julianne Newmark

When establishing the Psychological Shortcoming it’s often useful to ask what a main character is wrong about. (Julianne puts it so well):

We know [the narrator’s] situation in New York City is somewhat unique, as a young woman far away from home in the city alone for her studies, and we know that she perceives the young married couple as very much in love and “happy,” in the early pages of her story. She thus reinforces the traditional trajectory for a woman’s life: marriage and then child-rearing. These she equates with “happiness.”

Julianne Newmark

Susan Faludi wrote an entire book about this, but as it specifically applied in America after the 9/11 attacks:

when we base our security on a mythical male strength that can only increase itself against a mythical female weakness — we should know that we are exhibiting the symptoms of a lethal, albeit curable, cultural affliction.

All of women’s aspirations — whether for education, work or any form of self-determination — ultimately rest on their ability to decide whether and when to bear children.

Susan Faludi, Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women

However, the terrorist attacks only served to strengthen a phenomenon already in force. The Shortcoming of this narrator at the beginning of the story is the personification of a societal one: Don’t sit back and yearn for men to save whatever is wrong with the world. Failure to step up is the narrator’s Moral Shortcoming.

DESIRE

The narrator has been brought up to rely on men to step in and save the day. In short, the narrator wants a man to step in as patriarch of the apartment complex.

This is so she doesn’t have to do anything herself, other than exist.

This is a cultural comment on accepted gender divisions of the 1930s, but it’s still in play today, evident less at a household level perhaps, but still most alarmingly evident in politics. I’m talking about the idea we’re seeing around the world right now — that ‘good people’ need a ‘strong man’ leader to save everyone from those foreign, evil men.

OPPONENT

As viewpoint character, the narrator of this story is not the character involved directly in the web of Opposition. Like us, she bears witness.

The violent, surface opposition exists between the husband and his wife, then between the cat-like man and the cellist.

The married man above the cellist is perhaps using the cellist as a proxy wife upon whom he exacts his deep-seated misogyny. (It would be too much against his morals to attack the woman he married for his woes — easier to criticise some other woman, objectified as ‘loose’.)

Who is the married man avenging, really, when he yells at the cellist to be quiet even though she is in the middle of being manually strangulated? (By the way, despite what movies tell us, this often leads to real, long-term, life-changing physical injury.)

The married man’s real — though unacknowledged — opponent is a society in which men lose masculine privilege when suddenly unable to provide economically for their families due to forces beyond their control.

It’s dangerous to read too much into connections between fiction and its author’s life, but I was interested to learn that as a youngster, Carson McCullers would practice Bach fugues on the piano for five hours a day. I suspect that puts the author’s sympathies more firmly with the cello player than with the viewpoint narrator.

PLAN

Directly linked to the narrator’s moral shortcoming — that she waits around for a man to save the day — is the fact that she makes no Plan. Her only plan is to observe and hope.

In this case, other characters in a story must make plans, though ‘plan’ is a bit of a weird word when describing actions that take place out of rage — or perhaps it wasn’t rage. Perhaps when the husband raped the young cellist he was undertaking a well thought-out plan to keep her in her place. It’s a myth that murderous, violent people ‘just snap’. Often their attack is cool, calm and well-calculated, more like Hannibal Lecter than The Incredible Hulk.

BIG STRUGGLE

On first reading I wondered if there had been a murder, and that the sounds refer to manual strangulation. Did you think that, too?

It is soon revealed that the Battle sequence culminated in assault, probably sexual. This was carried out by the cellist’s male visitor — described only as a cat (who comes and goes in the night). The other men nearby either shout at her to be quiet (the married man) or look on, doing nothing (the red-headed man).

(Cats are very useful to storytellers. When femme coded characters are described as cats, the result is often sexualisation. When masculo coded characters are described as cats, it’s often more reminiscent of a big cat who can kill you.)

ANAGNORISIS

The narrator does not undergo a complete Anagnorisis, choosing to continue with her belief that the red-headed man will still save them all from bad in the world. But now she is actively ‘choosing’ to believe this, and you can’t ‘choose’ to believe something unless you know there’s more underneath, right? And since the narrator is telling this story herself, she must understand that the red-headed man is not going to save anyone — that no one is going to save anyone else, because we are all caught up in our own small day-to-day lives.

This type of short story ending is therefore in keeping with Literary Impressionism, because the Impressionists didn’t believe people changed all that much, and if they did, it was only very slowly, not in epiphanies.

As Julianne Newmark explains at her blog, the narrator’s arc is shown to the reader by the motif of borders:

McCullers’s story is, though not as overtly, a story concerned with a woman’s development (the narrator is in the city to be educated), with borders (the distinctions that reverberate in McCullers’s work between North and South), and with other kinds of borders . . . such as the physical ones that separate her from her neighbors in the apartment building, such as the “age” ones that make it hard for an eighteen-year-old woman to get a job in New York City, as she says, and the class borders on which the narrator comments upon her realization that her married neighbors are becoming increasingly “poor” even though their building is not a building occupied by poor people and it does not look shabby at all from the outside. This young narrator is learning a lot about the transgression of borders and the maintenance of them in this story, even though she doesn’t comment on this directly.

Julianne Newmark

To comment on them directly would mean she has experienced a complete emotional arc. But the narrator is still young at time of writing. Carson McCullers only lived until the age of 50, so never experienced the long hindsight of old age.

NEW SITUATION

The reader can extrapolate that the red-headed man will go to his next place and live in a very similar fashion. People are creatures of habit.

The young woman who was assaulted will continue living with trauma. She has already changed her habits, symbolised by the fact that she no longer dries her stockings where others can see them. (This simple detail is psychologically telling — she blames herself for the rape, at least a little. And she thinks that if she is careful enough, it won’t ever happen again. Another form of self-delusion.)

The narrator’s fate remains less clear: Self-delusion is to her huge psychological advantage, after all. I am somewhat envious of those who successfully convince themselves everything is fine even though it’s clearly not (e.g. climate change deniers, ‘egalitarian’ women who eschew ‘feminism’, believing gender equality has been achieved). There are huge penalties for seeing injustice at close range, especially if this insight leads us to action.

We are highly rewarded for conforming to gender expectations as well. There is a lot at stake for this young woman narrator if she were to fully realise and accept her own gender equality, and the idea that perhaps it was herself — not just the Jesus figure of the red-headed man — who could have done something to help the cello player that night.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

FOR THE ANAGNORISIS

I am fascinated by people’s ability to choose self-delusion. (Some better than others.) Although I only read McCullers’ story this week, I made use of the same Anagnorisis arc in our picture book app Midnight Feast (2014). The main character Roya looks out the window, sees that she is surrounded by homeless and starving people, then makes the active choice to retreat into her imagination, which includes imagining they don’t exist.

FOR THE NARRATION

Contrast this narrator with the narrative voice of Alice Munro’s short stories. Elderly women often look back on their younger years with a full understanding of who they were then and how they were shaped by their environments. This is then juxtaposed with the clarity of hindsight they have now. Clarity of hindsight is evident across Munro’s work even when the narration is (close) third person (rather than first, as it is here).

FOR THE STORYWORLD

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window is also the story of someone quietly observing his neighbours, eventually witnessing a crime. In the trailer for this 1954 film, notice how the camera moves like a fish swimming through water. Again, this is ocean symbolism at play, showing that the city is a dangerous food chain where bad things can suddenly happen.

Carson McCullers herself was partially paralysed by strokes by the time she was thirty. I imagine this made her an acute observer of her neighbours at time, similar to the character in Rear Window, who is laid up with leg injury.

FOR THE NARRATIVE VIEWPOINT

We remain fascinated by viewpoint narrators spying in on other people’s lives. The Girl On The Train was the tentpole psychological thriller of 2015, and led to many more like it.

Header photo by The New York Public Library