Do humans see reality as it really is? This is a fundamental question behind cosmic horror and is one philosophers and deep thinkers still ponder today. If H.P. Lovecraft had been born 100 years later he’d be fascinated with theories such as proposed by Donald Hoffman — that humans have evolved to see only a veneer of reality, not reality itself.

COSMIC HORROR: A SUBCATEGORY OF A SUBCATEGORY

fiction > fantasy > supernatural fantasy > gothic horror/fantasy > psychological horror > cosmic horror

Supernatural fantasy gathered steam around 1887.

Cosmic horror is a subgenre of Gothic narrative from this Golden Age of Supernatural Fiction. This Golden Age was drawing to a close by the start of the 1910s. Standout examples of supernatural fiction include:

- The first volumes of M. R. James’s ghost stories

- Algernon Blackwood short stories and novella such as “The Wendigo” (Audio version: Part One, Part Two)

- Bram Stoker’s Dracula

- Arthur Machen’s “White People“

- Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw is still popular with modern audiences due to over 30 TV adaptations, most recently The Turning and The Haunting Of Bly Manor. Before that the best known was probably The Innocents (1961), starring Deborah Kerr, a screenplay by Truman Capote and John Mortimer.

“The ambiguity of The Turn of the Screw goes way beyond ‘are the ghosts real or not?’,” says Dara Downey, a lecturer in English at Trinity College Dublin and editor of The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies. “Once you start reading it, you realise that nothing in it is really clear – who the governess is, where she’s writing from, what she sees, why she thinks what she thinks about the children, what happens at the end, what we’re meant to take from the story, what those men in the room hearing the story think of it, and so on.

Neil Armstrong, BBC

I have heard writers say the descriptor ‘American Gothic’ is pretty much useless because it seems to describe everything literary written in the American South, ever, and Armstrong seems to be using it here to describe an American strain of cosmic horror:

“In the 1908 Preface to the New York edition, James says that he wants to make the reader ‘think the evil, make him think it for himself’. So, in other words, he never tells us what the ghosts might be doing or saying to the children, or what happened in the house before the governess got there, so we project our own worst nightmares onto it. The fact that James was writing around the same time as Freud makes it so tempting to read something sexual into it, but really it could be anything. The book is part of a long tradition of American gothic from the 16th Century, building on the Puritans’ fears of devils, the unknown, their own sins, witchcraft, possession, ‘Indians’ in the woods, and so on. I think this makes the book perfect for continual reimagining – each era will emphasise what it most fears.”

Neil Armstrong, BBC

We fear what we don’t understand.

H.P. LOVECRAFT

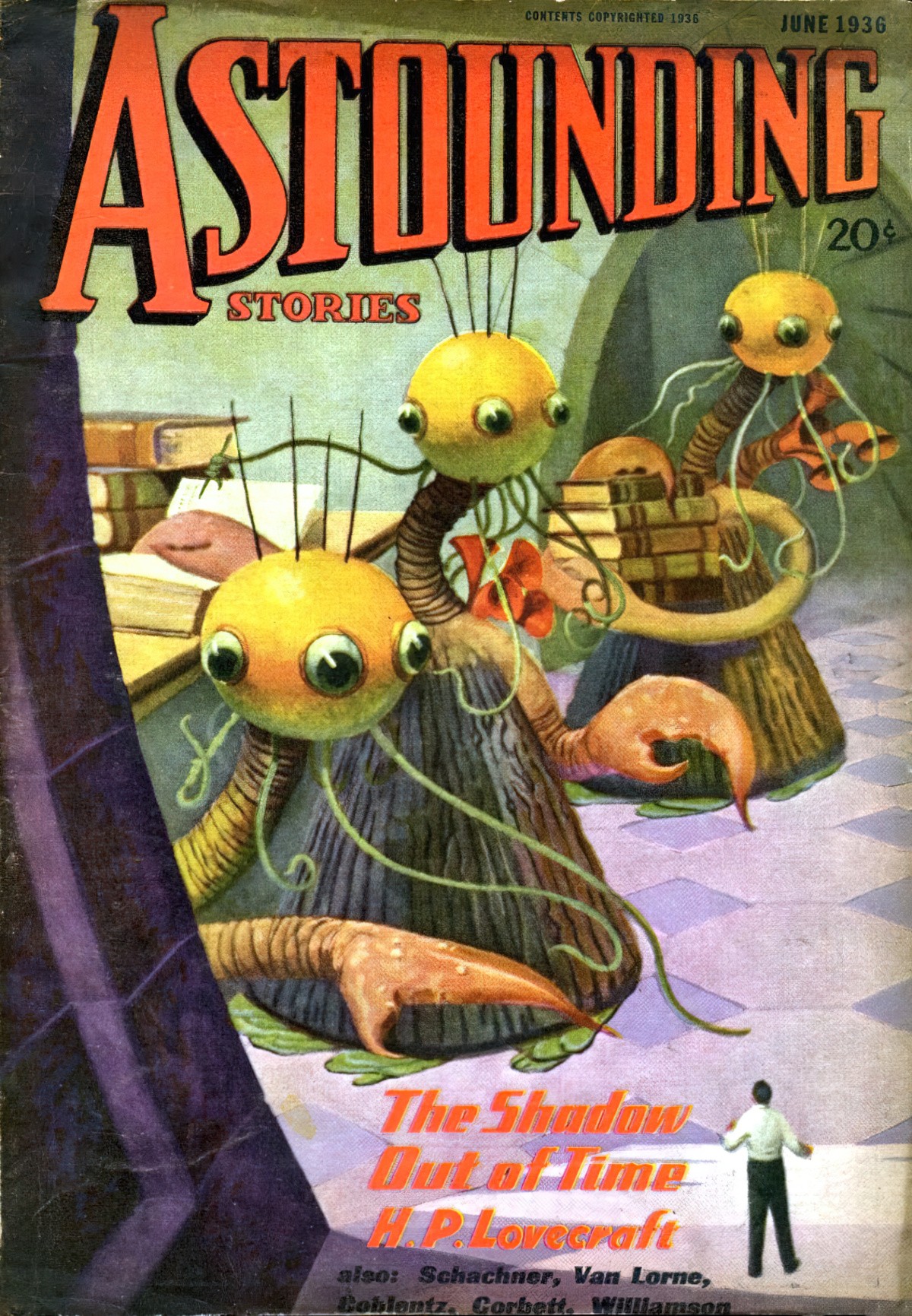

The name most synonymous with cosmic horror is H.P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), with an entire literary movement named after him. But Lovecraft has one of those sad, starving artist biographies. He lived in poverty and died in obscurity at the young age of 47. He never lived to see how influential he’d become on 20th century literature and beyond. (Aside from his raging racism) Lovecraft is best remembered for the following:

- “The Call of Cthulhu“

- “The Rats in the Walls” (I’ve analysed that here.)

- At the Mountains of Madness

- The Shadow over Innsmouth

- The Shadow Out of Time

Cosmic horror was heavily influenced by the Golden Age of Supernatural Fiction. We know this for sure because Lovecraft himself said he was influenced by Henry James (1843 – 1916), Arthur Machen (1863 – 1947) and Algernon Blackwood (1869 – 1951).

Lovecraft was very interested in a narrow set of tropes, notably: ‘Common human laws and emotions have no significance in the vast cosmos at large.’ Lovecraft also questioned his Christian background at a very young age, counting Jesus as mythological as Santa Clause. For his stories, Lovecraft became far more interested in ancient myth than in Bible stories.

H.P. Lovecraft was also influenced by the nineteenth century art of Gustave Doré.

Unfortunately, Lovecraft was a raging racist even more than average a white man of his time. He saw people of colour as the monsters, no different from the unknowable cosmic horror villain. Lovecraft couldn’t understand people different from himself, and didn’t want to. Ironically, to Native Americans, white people were the cosmic horror. Lovecraft sided with literal oppressors while successfully putting himself imaginatively in the shoes of the victims.

COSMIC HORROR AND LITERARY IMPRESSIONISM

The two movements share something big in common: It’s impossible for any single person to have a handle on veridical reality. There are techniques used by the literary Impressionists which emphasise this theme (e.g. parallactic viewpoints). Literary Impressionist art asks an audience to reconsider their own viewpoints, and accept that there’s always more to a story than our own individual point of view.

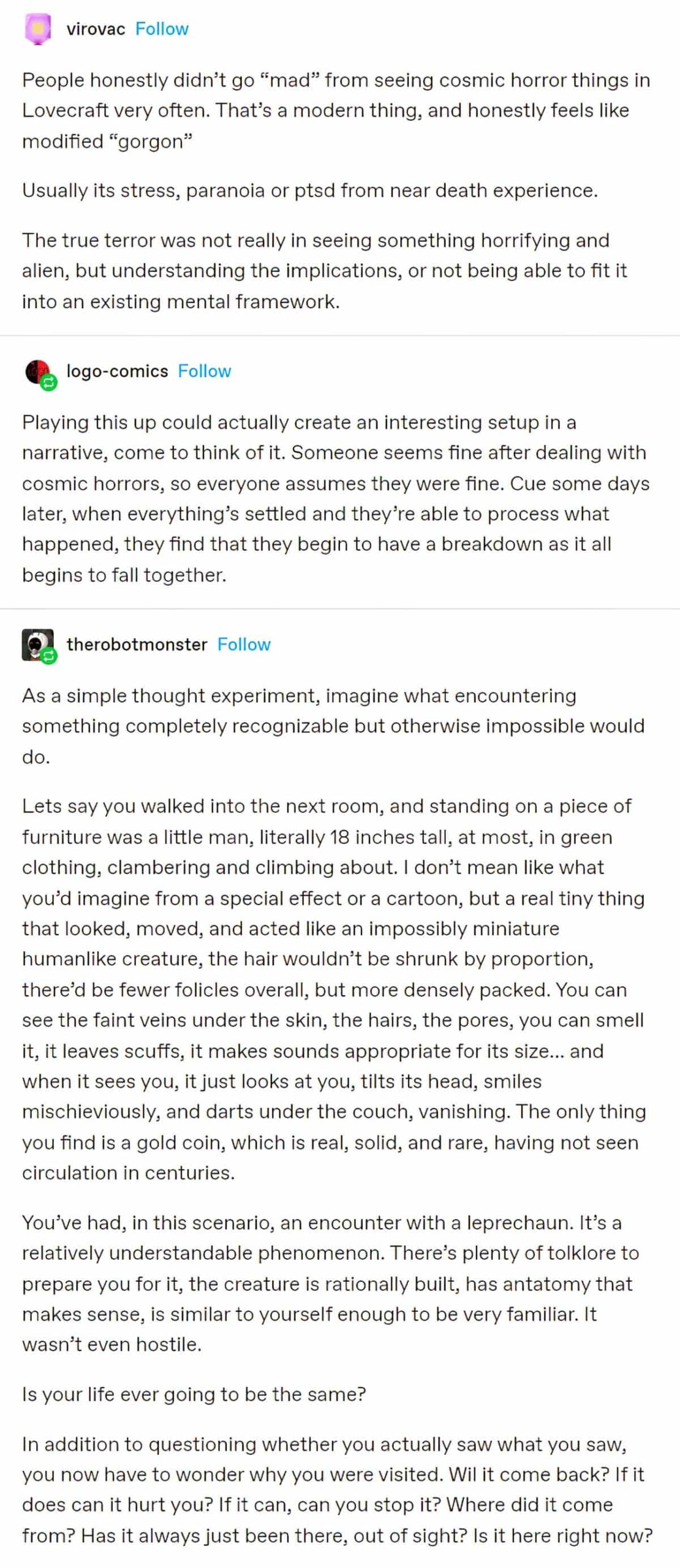

Cosmic horror kicks this aspect up to horror levels. It can be terrifying to realise you’ve been very, very wrong about the entire nature of being.

Both movements happened around the time people’s minds were starting to be expanded by big, mind-blowing advances in science. The more we know about the universe, the smaller we feel.

FEATURES OF COSMIC HORROR

The literary movement is known as ‘cosmicism’.

What makes cosmic horror ‘horror’? Cosmic horror typically makes lighter use of suspense techniques than other genres such as thriller and even other kinds of horror.

What replaces suspense techniques to create narrative drive?

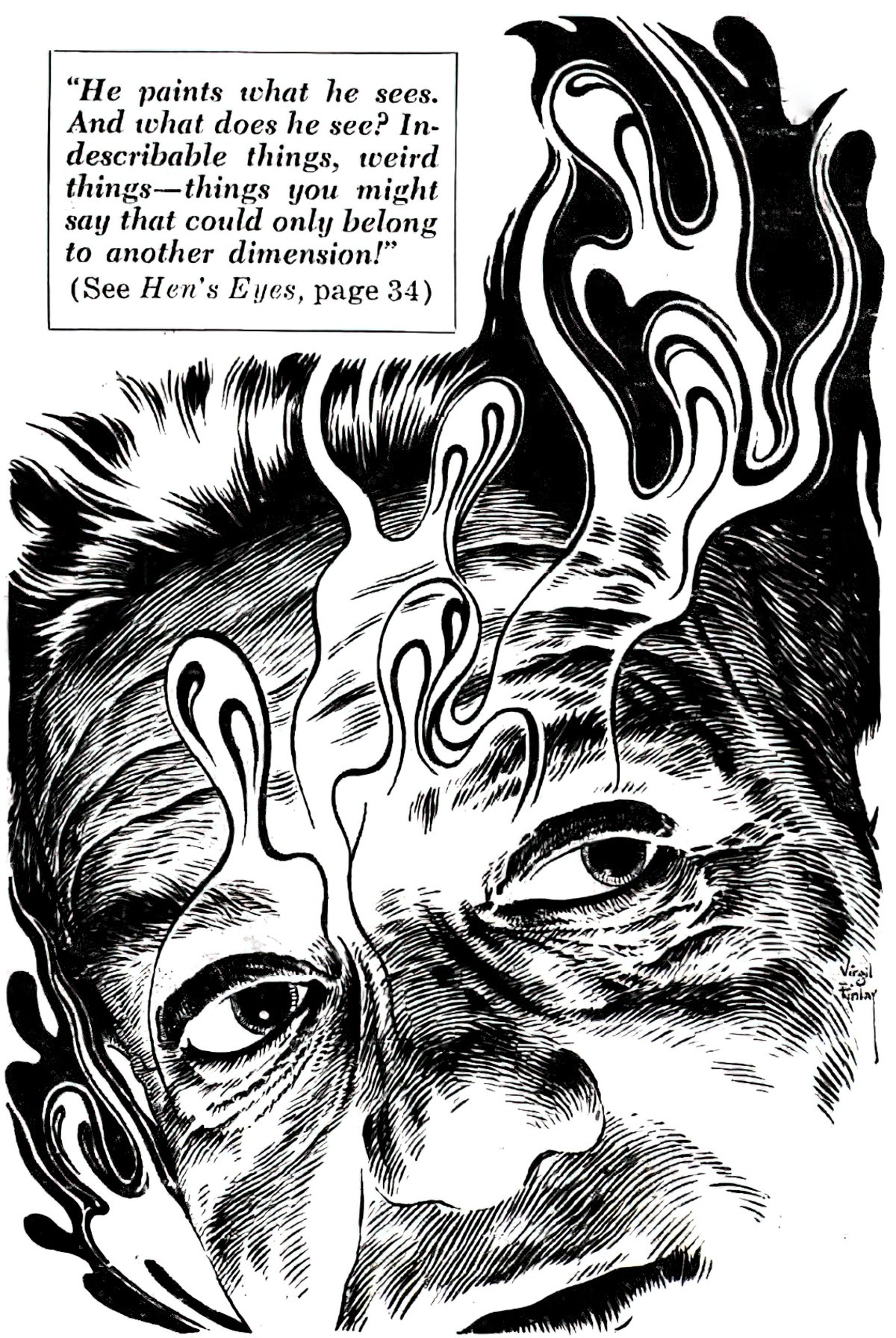

Well, cosmic horror traditionally makes use of its own kind of suspense, akin to the widely utilised technique of leaving the scary thing off the stage of the page, revealing to the viewer only an ominous shadow. To modern audiences, however, when a cosmic horror viewpoint character is so overwhelmed by what they’ve seen that they’re rendered speechless, this can feel like a cop out.

In cosmic horror, it’s all about the physiological response. Good horror creates a sensation known as ‘horripilation’ in its audience. This is the feeling that the hair on the back of your neck is standing on end. Cosmic horror achieves this by asking its audience to feel, if only for a moment, that there is way more out there than we can ever know. Humans are vulnerable, ignorant and at the mercy of greater forces. But how, then, is cosmic horror different from psychological horror more generally?

It’s partly in the themes.

THEMES OF COSMIC HORROR

Thematically, cosmic horror exists to subvert matters of value. Whatever humans value is no longer valuable in the world of cosmic horror. Conversely, whatever humans ignore is actually the most important. (Also terrifying.) The message will be this: humans have got everything wrong.

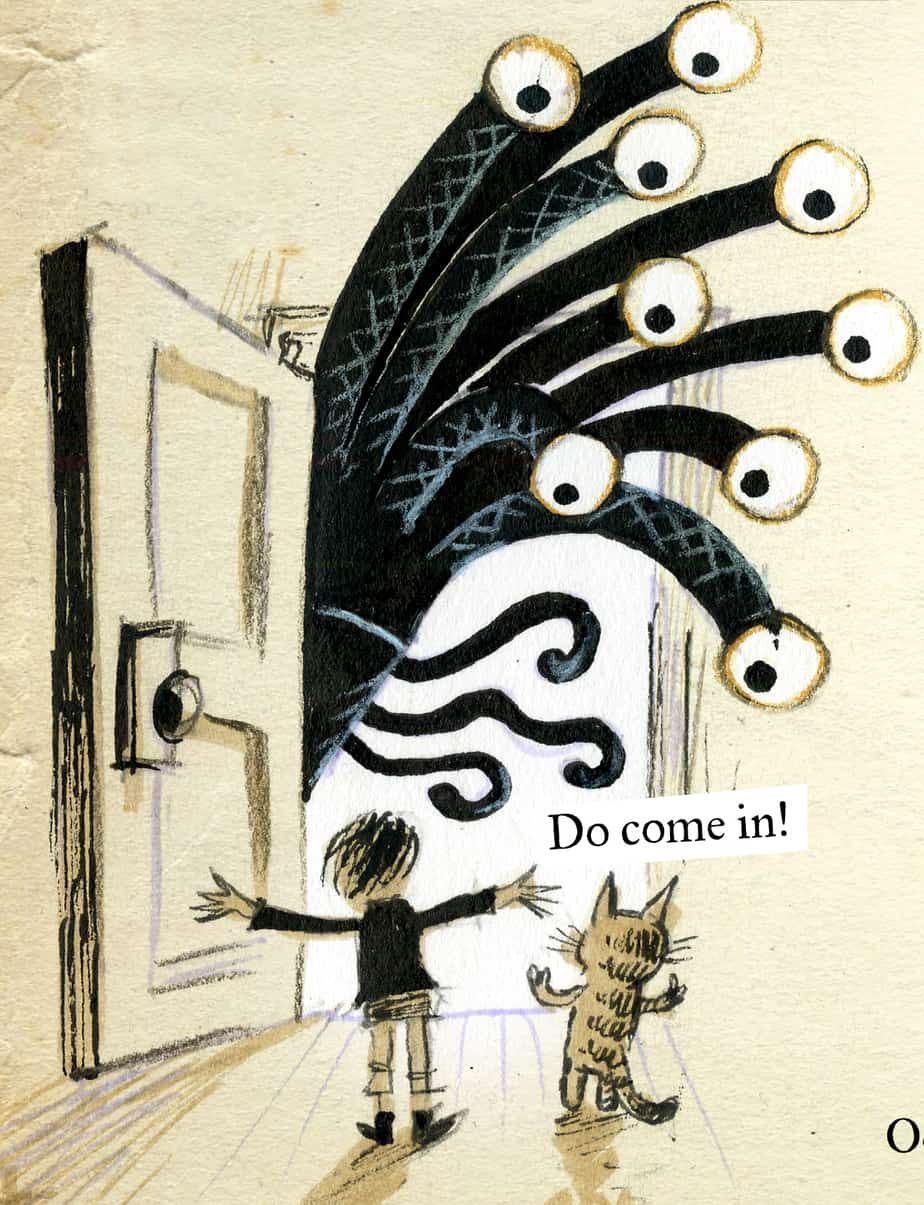

For this reason the picture books of Shaun Tan count as cosmic horror. The Lost Thing is a perfect example of a weird world which exists just beyond the visible world of adults. Across children’s literature, children are able to see what the adults cannot, until they age out of it, or learn to harness their childlike view of reality, unencumbered by the slog of capitalism and consumerism.

COSMIC HORROR AND THE MOVIES

In each of these examples, human order falls apart simply due to the existence of something much bigger than ourselves. In some plots the humans have gone looking for it; in others the ‘beast’ has been awoken. That said, if each of these films count as cosmic horror, the definition has been expanded, or the nature of modern cosmic horror has changed.

- Alien (1979)

- Event Horizon (1997)

- Cabin In The Woods (2011)

- The Ritual (2017)

- Annihilation (2018)

Cosmic horror remains popular because we’re still dismounting from ‘The Great Chain Of Being’ notion that humans exist at the top of the animal hierarchy. If you’ve lived your whole life thinking God created the world for you, then it can be terrifying to ponder an alternative — that no one gives a hoot about you. You are but a speck in the universe.

CHAIN OF BEING: An elaborate cosmological model of the universe common in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The Great Chain of Being was a permanently fixed hierarchy with the Judeo-Christian God at the top of the chain and inanimate objects like stones and mud at the bottom. Intermediate beings and objects, such as angels, humans, animals, and plants, were arrayed in descending order of intelligence, authority, and capability between these two extremes. The Chain of Being was seen as designed by God. The idea of the Chain of Being resonates in art, politics, literature, cosmology, theology, and philosophy throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. It takes on particular complexity because different parts of the Chain were thought to correspond to each other.

Literary Terms and Definitions

Cosmic horror asks us to consider our own mortality, but also our own reason for being, and the futility of jostling for place in the human hierarchy.

A theme that runs through classic cosmic horror: cults. This is partly why modern commentators consider The Ritual an example of cosmic horror.

“Little Runmo” (2019) is an example of cosmic horror. The ‘life’ of a side-scrolling computer game is peak expendability.

You can find cosmic horror techniques in children’s literature. Take the following example from Carrie’s War by Nina Bawden, a middle grade novel from the early 1970s. Two children have been sent from London to the country to provide safety during the war, Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe style. There’s a patch of woods which have a very druidy feeling about them. On the way to collect a goose one day:

She couldn’t explain it. It was such a strange feeling. As if there was something here, something waiting. Deep in the trees or deep in the earth. Not a ghost — nothing so simple. Whatever it was had no name. Something old and huge and nameless, Carrie thought, and started to tremble.

Carrie’s War, Nina Bawden

CHARACTER SHORTCOMING

In the character set up, the main character will have some kind of shortcoming and they will typically be wrong about something. In Cosmic Horror, ‘being wrong about something’ is central. There are monsters; the main character does not believe in monsters. Whatever the main character is wrong about equals what readers in general are wrong about. Cosmic horror says, “The mundane will cloud your view of reality. Pay attention and you’ll see what’s really there.”

Aside from this, the main character of cosmic horror is the Every Man or (very rarely) the Every Woman. They function as a viewpoint character. They arrive to the stage (or page) in statu nascendi (without backstory). Sometimes when writers create characters they want to make them as relatable as possible in a short space of time. They’ll be saving cats, suffering injustices, reacting in relatable ways. The viewpoint characters of cosmic horror aren’t written in this way. If they happen to be relatable it’s precisely because we know very little about them. The story uses human viewpoint characters as the story sees fit. (We don’t really want to fall in love with the viewpoint characters of cosmic horror because they may not live to see the story out…)

In cosmic horror, the world is more important than the character. In transgression horror the mask comes off the character; in cosmic horror the mask comes off the world.

By the way, in the early cosmic horror tales sometimes the viewpoint character would be one removed: This story happened to my friend. Now I’m visiting him in the lunatic asylum. He went mad and is unable to recount the story himself. See: Go Mad From The Revelation at TV Tropes.

As you can probably guess, in the wrong hands Cosmic Horror can take a turn for the horribly ableist.

DESIRE

Whatever the viewpoint character thought they were going to be doing with their day gets rescheduled when they come across something even more horrifying than they’d imagined.

OPPONENT

The web of opponents works the same as in any horror — there will probably be infighting between the humans, with all their different desires and weaknesses, and this infighting pales in comparison to whatever master force reigns supreme.

The big bad evil force is your typical horror villain — pure evil. Much Western horror makes use of Christian symbolism and thought, with the rituals of Catholicism. Although rarely explicit, if we think about this, any evil manifested in human concepts of hell can’t have existed prior to religion.

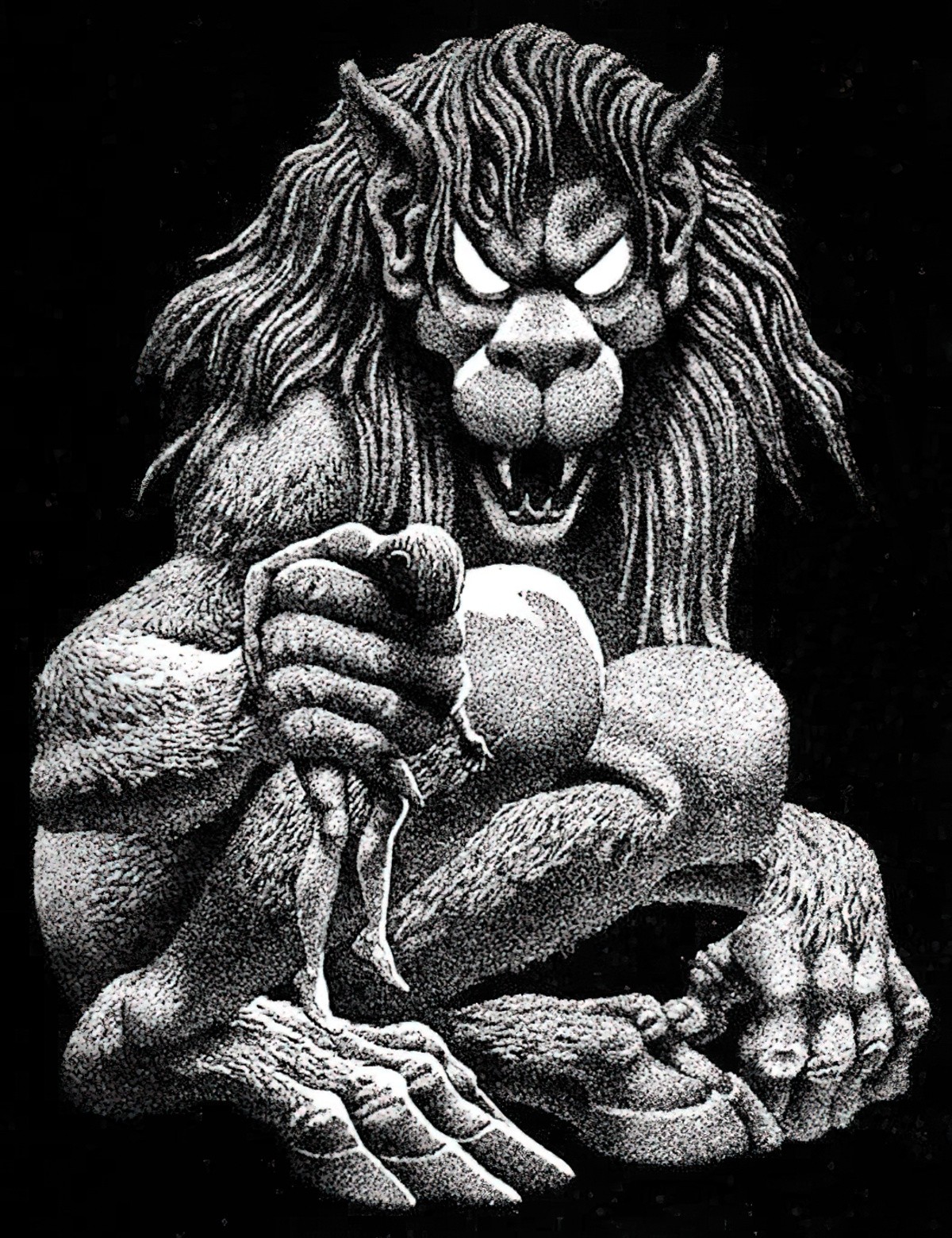

The overwhelming force of Cosmic Horror is sometimes called an ‘Eldritch Abomination‘. Eldritch is an English word used to describe something otherworldly, weird, ghostly, or uncanny. In contemporary culture, the term is closely associated with the Lovecraftian horror.

This is where cosmic horror is a bit different from other types of stories. The Eldritch Abomination in cosmic horror predates religion and even predates humans. It’s probably not even from this world, and may come from a different dimension entirely. Cosmic horror feels to me like an attempt to reject religion by writers who were nonetheless steeped in religious views of the world. As much as they try to nihilistically reject the gods, their fiction keeps coming back to godlike, omniscient, all-powerful… well… gods. Malevolent gods, but gods all the same. (The ancient gods weren’t all that great.) Of all the ancient forces, they are quire like the Djinn, who have been around for far longer than humans have. The Djinn can even fly between solar systems, so their arena is way more massive than ours, as well.

In any case, the humans can’t fight back against this kind of villain. The villain is way too ancient and powerful, and we can’t even understand their motivations, so they’re impossible to foil.

CTHULHU MYTHOS (also spelled Cthulu and Kutulu, pronounced various ways): Strongly influential in pulp science fiction and early twentieth-century horror stories, the Cthulhu mythos revolves around a pantheon of malign alien beings worshipped as gods by half-breed cultists. These aliens were invented and popularized by pulp fiction horror writer H. P. Lovecraft. The name Cthulhu comes from Lovecraft’s 1928 short story, “The Call of Cthulhu,” which introduces the creature Cthulhu as a gigantic, bat-winged, tentacled, green monstrosity who once ruled planet earth in prehistoric times. Currently in a death-like state of hibernation, it now awaits an opportunity to rise from the underwater city of R’lyeh and plunge the earth once more into darkness and terror. August Derleth later coined the term “Cthulhu mythos” to describe collectively the settings, themes, and alien beings first imagined by Lovecraft but later adapted by pulp fiction authors like Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, Henry Kuttner, and Brian Lumley. Some common elements, motifs, and characters of the mythos include the following:

- “The Great Old Ones,” an assortment of ancient, horrible, powerful (and often unpronounceable) deities/aliens including Cthulhu, Azathoth, Nyarlathotep, Shub-Niggurath, Hastur, Dagon, and Yog-Sothoth.

- “The Elder Gods/Elder Things,” A term used interchangeably with “The Great Old Ones” by Lovecraft, but used by August Derleth to refer to a separate group of aliens at war with the evil “Great Old Ones.” They serve as a deus ex machina in several short stories of the Cthulhu mythos.

- Servitor races, i.e., lesser alien species that worship and/or act as slaves to The Great Old Ones, including the shape-changing shoggoths, the intelligent fungus crabs (Mi-go) living on Pluto, the tentacled star-spawn, and the aquatic race of “Deep Ones” living near Devil’s Reef in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.”

- The imaginary town of Arkham, New England, used as a setting, along with nearby towns like Dunwich and Innsmouth along the Miskatonic river valley.

- The theme of insanity (often protagonists suffer mental breakdowns merely by viewing one of the Old Ones).

- The appearance of forbidden books of ancient and dangerous lore, such as the fictional Necronomicon, The Book of Eibon, and Unaussprechlichen Kulten.

from Literary Terms and Definitions

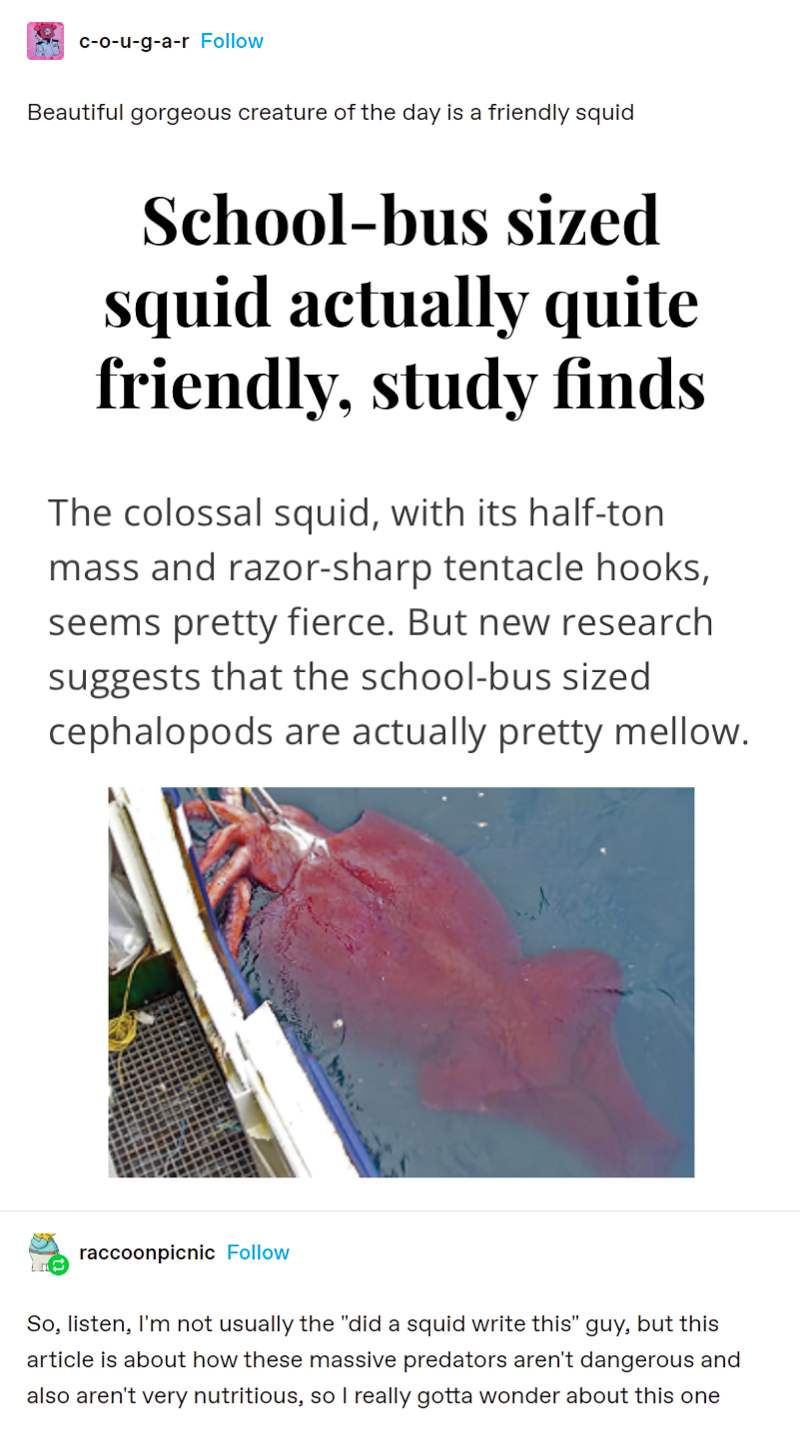

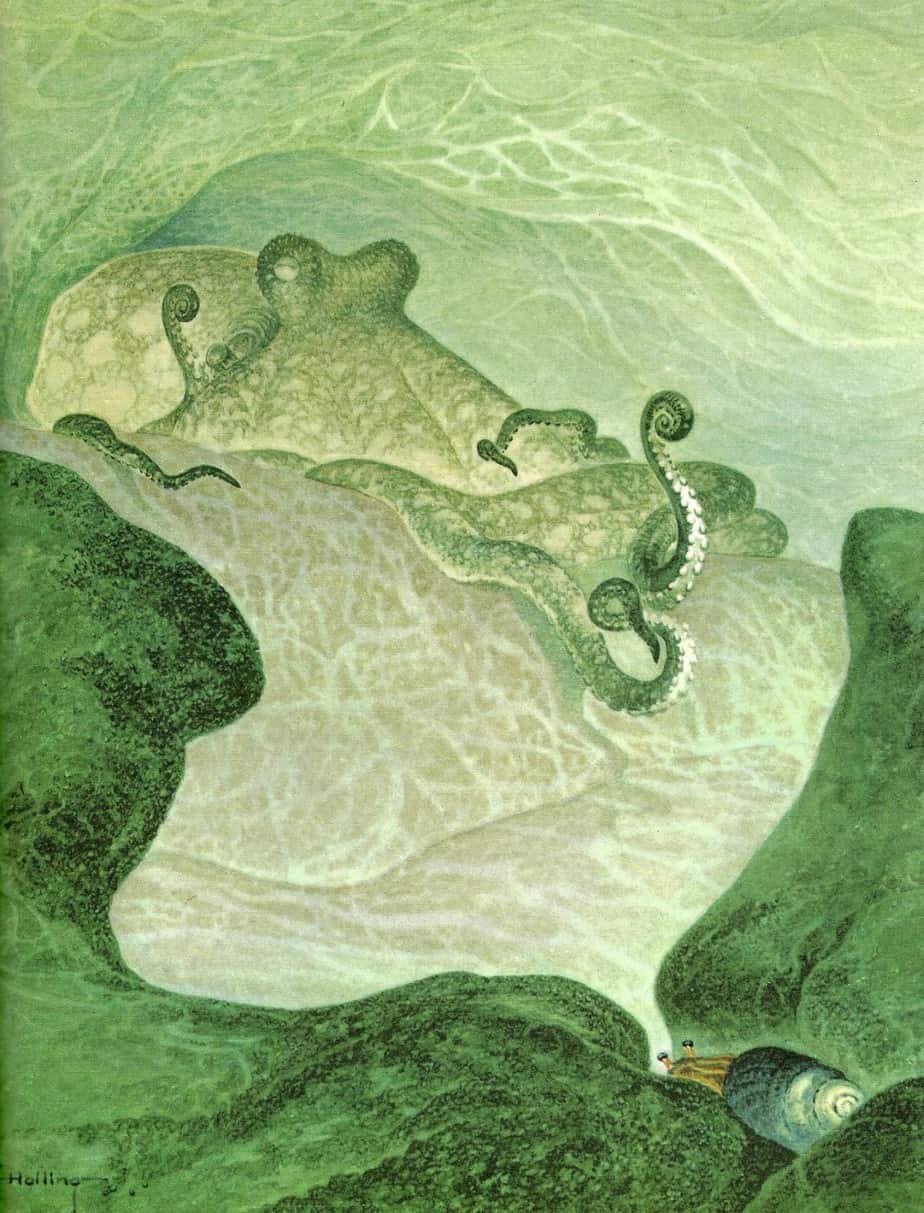

The Kraken is another well-known Lovecraftian opponent. The first description of a kraken (giant squid) reached England in 1755. According to newspapers, one washed up on the coast of Orkney in 1808.

PLAN

Once the viewpoint character realises there’s something fishy going on, they’ll want to find out more. So the plan will be around that.

STRUGGLE SEQUENCE

Spatial horror is a set of tricks storytellers use to make the audience feel bodily discomfort. As the terror progresses and enters the struggle phase the spatial horror intensifies.

Cosmic horror does not typically involve gore. Cosmic horror is a subcategory of psychological horror.

ANAGNORISIS

This has to be the scariest part of the story. The best of the best cosmic horror stories create a revelation in the reader as well as in the main character, and the reader should feel the whole world looks different, at least for a moment.

However, that poor sucker the viewpoint character doesn’t have the privilege of distance and rather than experiencing life-changing epiphany, goes crazy. The ‘going crazy’ part is a standard fixture of cosmic horror but think widely; they may lose their senses, they may (these days) suffer PTSD or psychological trauma. In any case, the human mind isn’t equipped to process the experience.

NEW SITUATION

In many well-known tales of Cosmic Horror, the main character dies at the end. This is partly why you don’t want the audience getting too attached to them.

Cosmic horror is difficult to write because it’s hard to awe a modern audience with a completely new idea. However, the subgenre makes for excellent parody. (Horror and comedy are a great genre blend.) Welcome To Night-Vale is a popular parody of cosmic horror, released as a podcast in the format of local radio. The Hitch-hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy can be considered parody of cosmic horror as well.

THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY

Suppose a good friend calmly told you over a round of drinks that the world was about to end? And suppose your friend went on to confess that he wasn’t from around here at all, but rather from a small planet near Betelgeuse? And what if the world really did come to an end, but instead of being blown away, you found yourself hitching a ride on a spaceship with your buddy as a travelling companion?

It happens to Arthur Dent.

An ordinary guy from a small town in England, Arthur is one lucky sonofagun: his alien friend, Ford Prefect, is in fact a roving researcher for the universally bestselling Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy … and expert at seeing the cosmos on 30 Altairian dollars a day. Ford lives by the Guide’s seminal bit of advice: Don’t Panic. Which comes in handy when their first ride–on the very same vessel that demolished Earth to make way for a hyperspacial freeway–ends disastrously (they are booted out of an airlock). with 30 seconds of air in their lungs and the odd of being picked up by another ship 2^276,709 to 1 against, the pair are scooped up by the only ship in the universe powered by the Infinite Improbability Drive.

WHERE IS COSMIC HORROR HEADED?

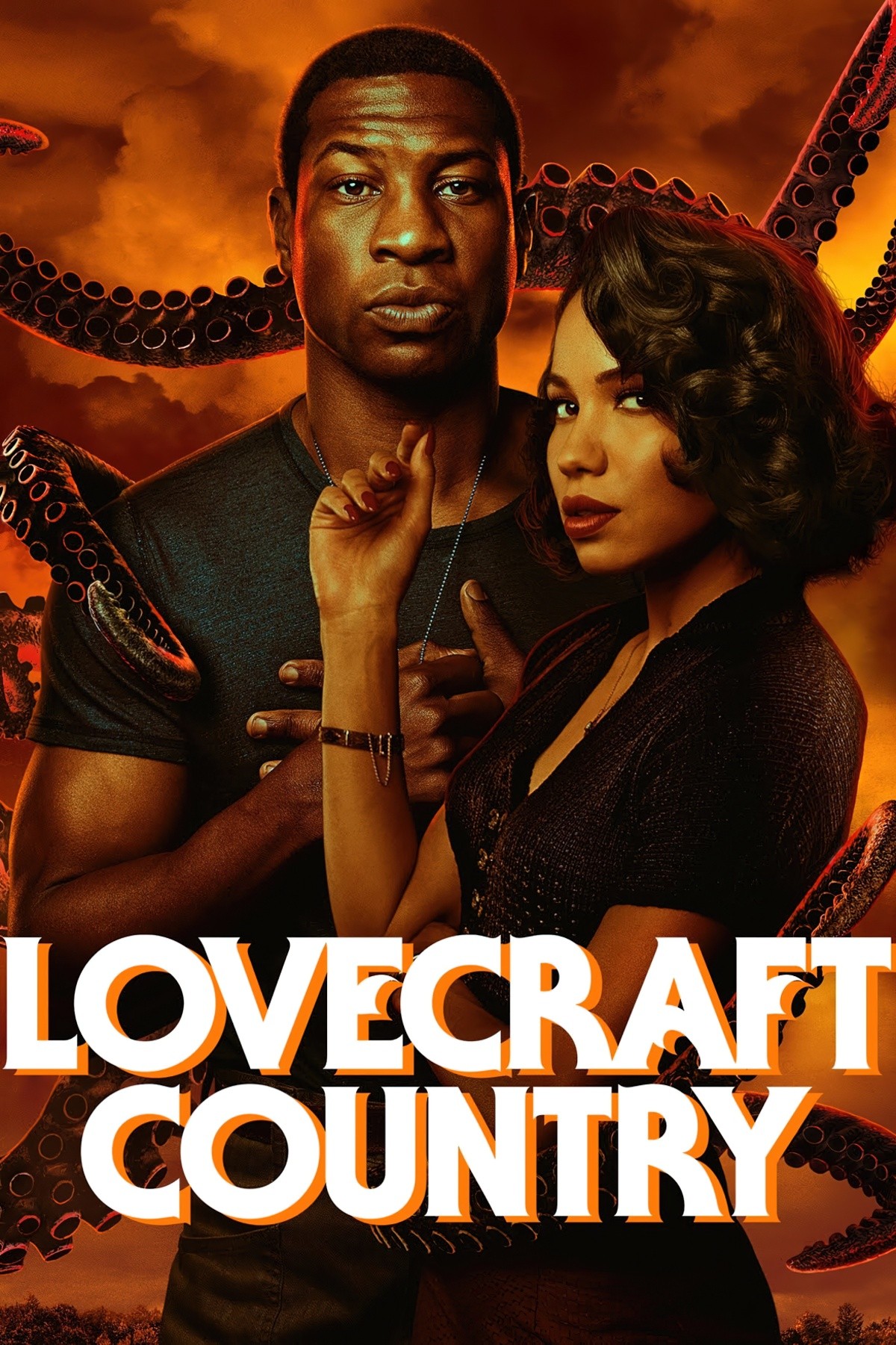

In the 21st century, cosmic horror is being wholeheartedly reclaimed by authors with various marginalised identities and intersectionalities.

Woman authors are creating main characters who are both femme and The Scientist.

Black, indigenous and authors of colour are inverting the story that Lovecraft told. An excellent TV series example is Lovecraft Country (2020).

Lovecraft Country follows Atticus Freeman as he joins up with his friend Letitia and his Uncle George to embark on a road trip across 1950s Jim Crow America in search of his missing father. This begins a struggle to survive and overcome both the racist terrors of white America and the terrifying monsters that could be ripped from a Lovecraft paperback.

‘Pure’ Cosmic Horror as it existed in the 20th century is no longer very interesting for contemporary readers, so modern cosmic horror tends to be a blend of cosmic horror and other kinds of speculative fiction, especially science fiction. This allows for character development, for starters, and can bring big ideas down to the personal level.

RELATED TERMS

Cosmic Irony: An alternative term for situational irony, especially when connected to a fatalistic or pessimistic take on life.

Cosmic Justice: A riff on ‘poetic justice’, in which natural consequences for an action take place in a story, in place of retributive justice meted out by humans, or gods.

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Episode 65 of the Our Opinions Are Correct podcast gives us all permission to skip Lovecraft. Really, you don’t need to read him unless you’re a completionist. We’re Officially Done with Lovecraft and Campbell