“The Contest” by Annie Proulx is a short story from the Bad Dirt collection, published 2004.

Like Larry McMurtry, Proulx writes two main types of stories — comical stories similar to those found in dime novels (in McMurtry’s case) and in hunting and fishing magazines (in Proulx’s case).

“The Contest” belongs to the comical class, and makes a great case study in satirical anticlimax. When writing an anticlimactic story we have to be careful not to make the reader feel like we have wasted their time. This one works, and it’s worth taking a close look at the story structure. Proulx has done something interesting with it.

SETTING OF “THE CONTEST”

This is a humorous tale, and a satire of smalltown Wyoming rural life, where parish pump politics rule, and where the usual human pecking order works by unusual rules.

Sayre’s Law: The lower the stakes, the more vicious the politics. In tense nuclear talks, people act civilized. In Twitter culture wars, people act like Armageddon has come, raging like maniacs, calling for total war, safe in the knowledge none of it matters.

@G_S_Bhogal

Utilised across about half of the short stories in her Bad Dirt collection, Annie Proulx created the small town of Elk Tooth.

The population is only 80, yet there are three bars in town—Silvertip, the Pee Wee, and Muddy’s Hole. Presuming the entire populace is of drinking age—not a bad assumption, considering their barren, infertile surroundings—that’s roughly one bar for every couple dozen citizens, which actually seems about right. Given the lack of a social scene on these arid prairies, and the rural tragedies that seem as common as they are strange, where else is there to go but a dive like the Pee Wee, which in one story (“The Contest”) sponsors a beard-growing competition? When there’s nothing else going on, watching whiskers sprout may be the most entertaining pursuit available.

The A.V. Club review

There’s a definite magical realist twist near the end of “The Contest”, but otherwise this feels like a slight exaggeration on what could be a real place. The exaggeration, of course, would come from a narrator skilled in the art of the tall tale.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE CONTEST”

Presumably because they have nothing else to do, the men of Elk’s Tooth start a beard contest. It’s meant to be a bit of fun but becomes mean spirited, as it seems to symbolise, to the men, their entire identities.

Before the contest is over, a newcomer arrives. The guy’s beard is luxurious to a comical degree. The men tacitly agree that the contest is over. They’ll find some new way to sort out the pecking order, and turn immediately to modes of transportation.

Why beards, though? For obvious reasons, beards are often a symbol for masculinity as a whole. Perhaps Proulx wrote this story to take the mick out of the pissing contests that so often go down between men in drinking establishments.

David Walliams makes fun of the same in a skit from episode one of David Walliams and Friend (the one featuring Jack Whitehall). A chav type (Whitehall) walks into a bar and says to the other man (Walliams), “I’m better than you.” Ridiculous dick-waving continues until the climax, in which it is revealed the Whitehall character is a virgin. This supposedly negates all his masculine features. So often, when male comedians try to subvert concepts of masculinity, they almost get there but ultimately fail. The idea that you can’t be a man unless you have sex with a woman is as damaging as the other markers of masculinity proposed by the chav character.

STORY STRUCTURE OF “THE CONTEST”

The structure of “The Contest” is very interesting. As I often do on this blog, I’d like to compare it to a children’s picture book. Children’s stories in particular are known to start with the iterative (a description of what happens all the time) and then switch to the singulative (But on this particular day…).

Proulx makes use of this switch, but in a children’s story the iterative introduction tends to be brief. After all, we don’t care much for what happens every boring old day. We want to know what happens on this particular day. Something unusual, you can bet.

But in “The Contest”, Proulx spends ten pages setting up with the iterative — sort of — and then the last three pages in the singular.

Here’s where it switches over:

On this April afternoon Creel was, aside from Amanda and Old Man DeBock, the only one in the bar.

It’s not quite as simple as that, because you could argue the beard contest is in itself a singular event. Structurally, though, the beard contest is exactly the sort of thing that happens all the time. So I’m treating this ‘one off’ contest as Annie Proulx’s way of telling us all the backstory of this town — how it works, who lives there, how the streets are laid out.

Unless we know this town, the singulative portion of the story doesn’t make sense. Even so, this is a story with a classic, anti-climactic ending.

The anti-climactic ending, when used in the extreme, is known as a shaggy dog tale, which I consider a subcategory of the tall tale — a regional, masculine tradition, in line with the narrative voice.

SHORTCOMING

Like many of Proulx’s stories, “The Contest” stars a community rather than an individual. The characters together make up a vision of one eccentric rural figure. Their shortcoming is their extreme isolation, and the insular thinking that inevitably results.

Proulx presents a society that is struggling and persisting at best – which is not especially likeable, but for which we still feel tremendous sympathy as it strains to comprehend the meretriciousness of modernity. She creates characters who, despite their tenacity and will, are somehow flattened against the landscape, beaten down, and whose tragedy is more everyman and woman than individual.

The Observer review of Bad Dirt

This is specifically about the men of the community, who are so similar to each other, really, that they can only distinguish themselves by superficial means e.g. by the colour, length and texture of their beards. As well as the David Walliams sketch, I’m reminded of the ridiculous happenings that Amish communities have become known for. When everyone is forced to live in exactly the same way, humans still have a way of pulling themselves up the pecking order, even if it means inventing an entirely new pecking order. When you’re only allowed to drive a horse and wagon, you can still trick out your wagon. The great irony of being human: the need to stand out and also the need to be like everybody else. (At least, for the neurotypical population.)

DESIRE

The men in “The Contest” want to be respected by each other. Since beards are a symbol of manhood, I guess they each want their manhood respected. (This requires being sized up by a woman — the bartender.)

OPPONENT

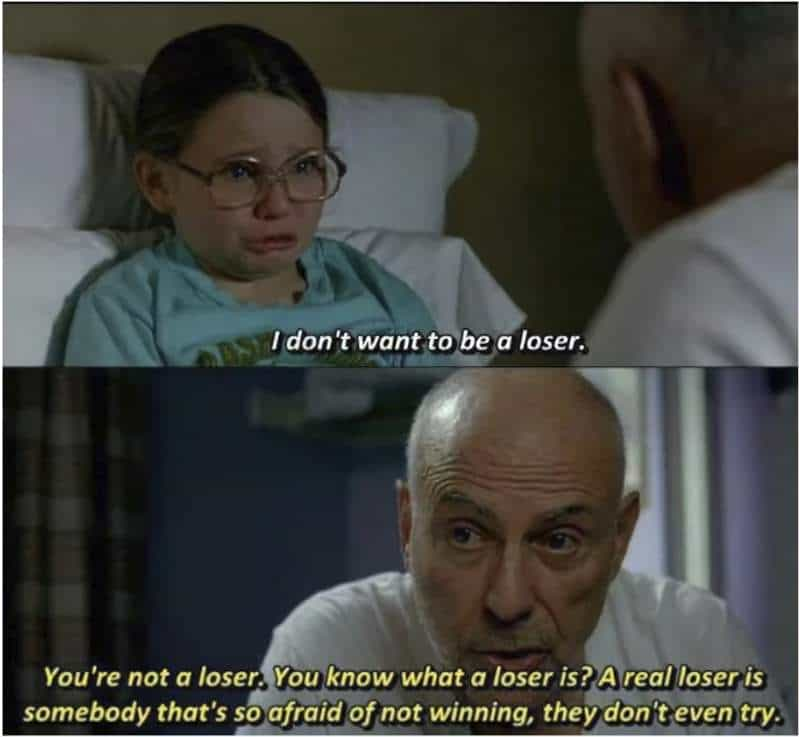

In a pissing contest like this, everyone entered automatically becomes everyone else’s opponent. But the stakes are very low. The prize money is insubstantial.

Despite internal rivalries, the community of men will band together in the face of a newcomer who will show them all up. The conflict in many, many stories works exactly like this: The ‘family’ start off fighting about something insubstantial, but as soon as the outsider baddie enters the story, they band together. I suppose it’s a popular progression because real life works like this. There’s no better way to cement ingroup bonding than by pitting the entire group against another group.

Ralph Kaups is the embodiment of everything sophisticated and foreign. By the end, two of the men, Creel Zmundzinski and Plato Bucklew have banded together. The symbolic opposition exists between country bumpkins and sophisticated blow-ins.

PLAN

There’s not much involved in growing a beard. In fact, you don’t have to do anything. If you’re the sort of person who can grow a beard, you just hang around waiting for it to grow. So how does one turn that plot starter into a fully-fleshed story?

Proulx knows that the beard contest is just the wrapper for something far more meaty — a detailed description of a town and its people, each with their own mini backstory.

A lot of language humour derives from Proulx’s comically detailed descriptions, in sentences with multiple descriptive clauses.

But a profusion of detail does not make a story. It still needs some kind of shape. For that, Proulx introduces a mystery — equally trifling — how did Bill de Silhouette catalogue his books before he up and died? This is important because they need to put their hands on a book about beards in order to settle bar disputes between them.

BIG STRUGGLE

The bar scene is very much like something out of a classic Western, with the shady newcomer barging in through the double swing doors. There are no guns here, but a clear winner nevertheless, symbolised not by the hue of the hat but by luxuriousness of beard.

The mystery of de Silhouette’s library cataloguing is solved when Bill’s widow happens upon a notebook with the key written down — a fitting anticlimactic solution within an anticlimactic tale.

“It was funny. I was cleanin out that big chest in the hall and I come on some a Bill’s notebooks. There was one he’d written on the cover. “Book Key.” I looked in it and it was the system he used. Made me mad he didn’t tell me about it before he went.”

ANAGNORISIS

Part of the humour revolves around the observation (revelation) that it takes outside intrusion to band a community together. Otherwise they’ll just keep fighting each other.

NEW SITUATION

We can extrapolate that the beard contest is over, because no one will want to give prize money to this up-himself blow in.

Now they’ll engage in arguments about who has the best motorcycle/car/horse/wagon. The hierarchy will be based not on who has the flashiest equipment, but on whose is the most eccentric, according to their own smalltown logic, which itself is a nebulous thing.

Bigger than that, a newcomer will psychologically band these rural men together, at least for a time, and the ‘cruel competitiveness’ will simmer down.

TAKEAWAY WRITING TIPS

- If writing a story in which nothing happens (e.g. growing a beard) it’s a good idea to introduce a mystery.

- If the plot ends in anticlimax (e.g. a competition is set up but no one really wins it), then the mystery can be anticlimactic, too.

- Opposition comes in two main forms — opposition between members of the same group (what sociologists call ingroup) and opposition from the outgroup. Stories tend to progress in two main ways: an outgroup opponent appears early and the ingroup members band together to fight them. Or, as in this story, an inversion on the usual, the bulk of the story revolves around ingroup bickering, and the outgroup opponent only arrives to finish things off.