Is it picture book or picturebook? When commentators put the two words together, they do so mindfully:

The terminology we apply to books, texts and reading do not seem to attach to the picturebook so readily. For example, if we speak of ‘the text’ of a picturebook, do we mean the words or the words-and-pictures together? … And when we say ‘read’ a picturebook does the word — and the process — apply equally well to the visual images and to the sentences and paragraphs alongside, or do we need another term that better represents the special relationship of picture and beholder?

from the introduction to Reading Contemporary Picturebooks: Picturing texts by David Lewis

The more detail in the words, the less room there is for pictorial invention.

from Reading Contemporary Picturebooks by David Lewis

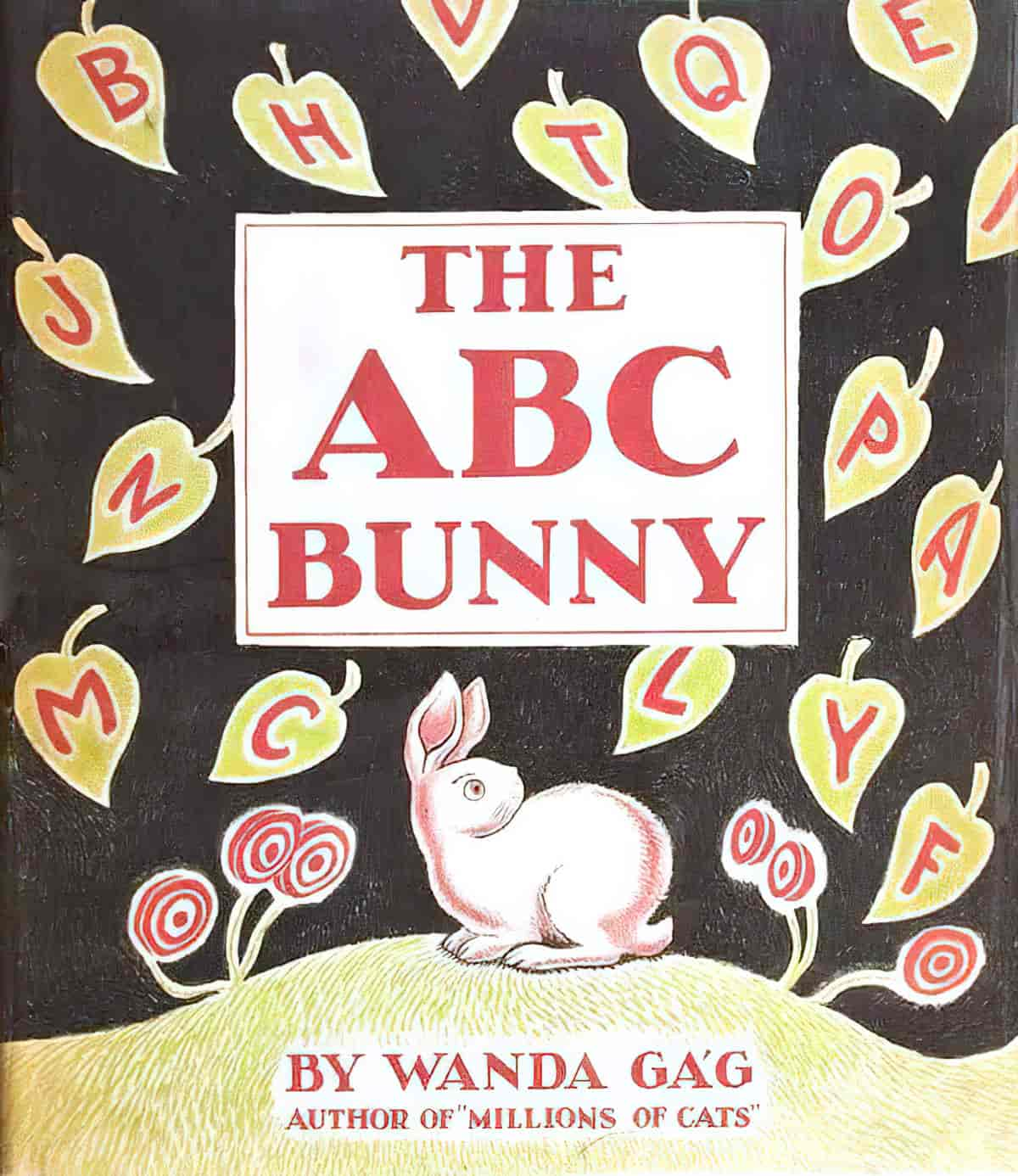

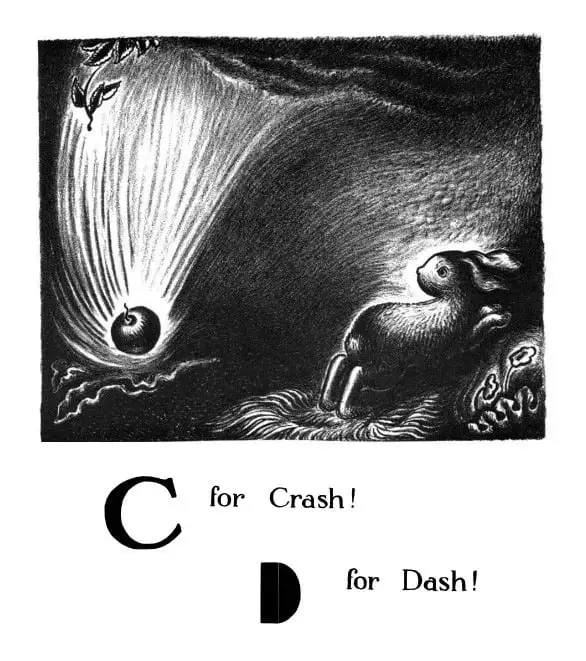

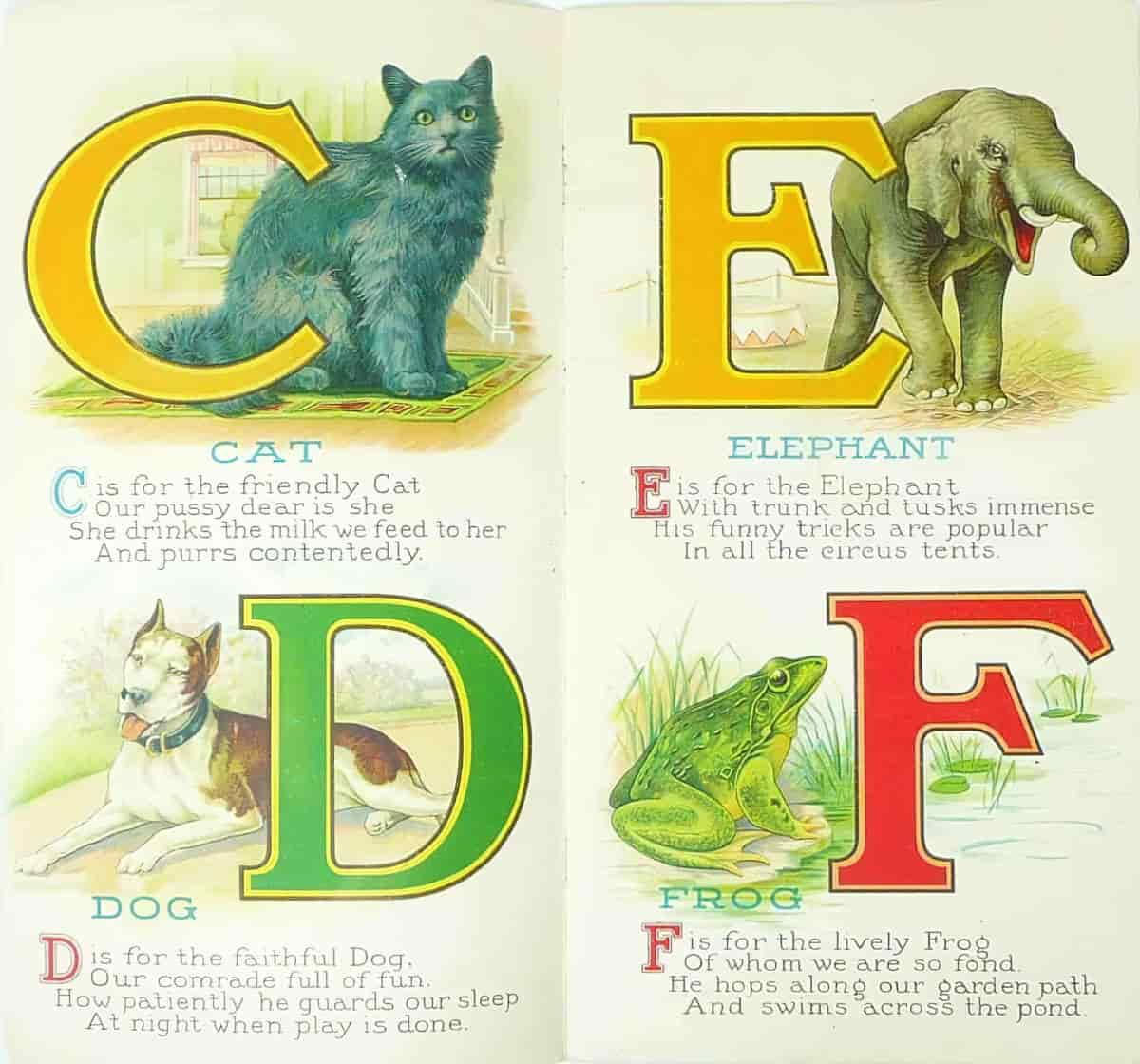

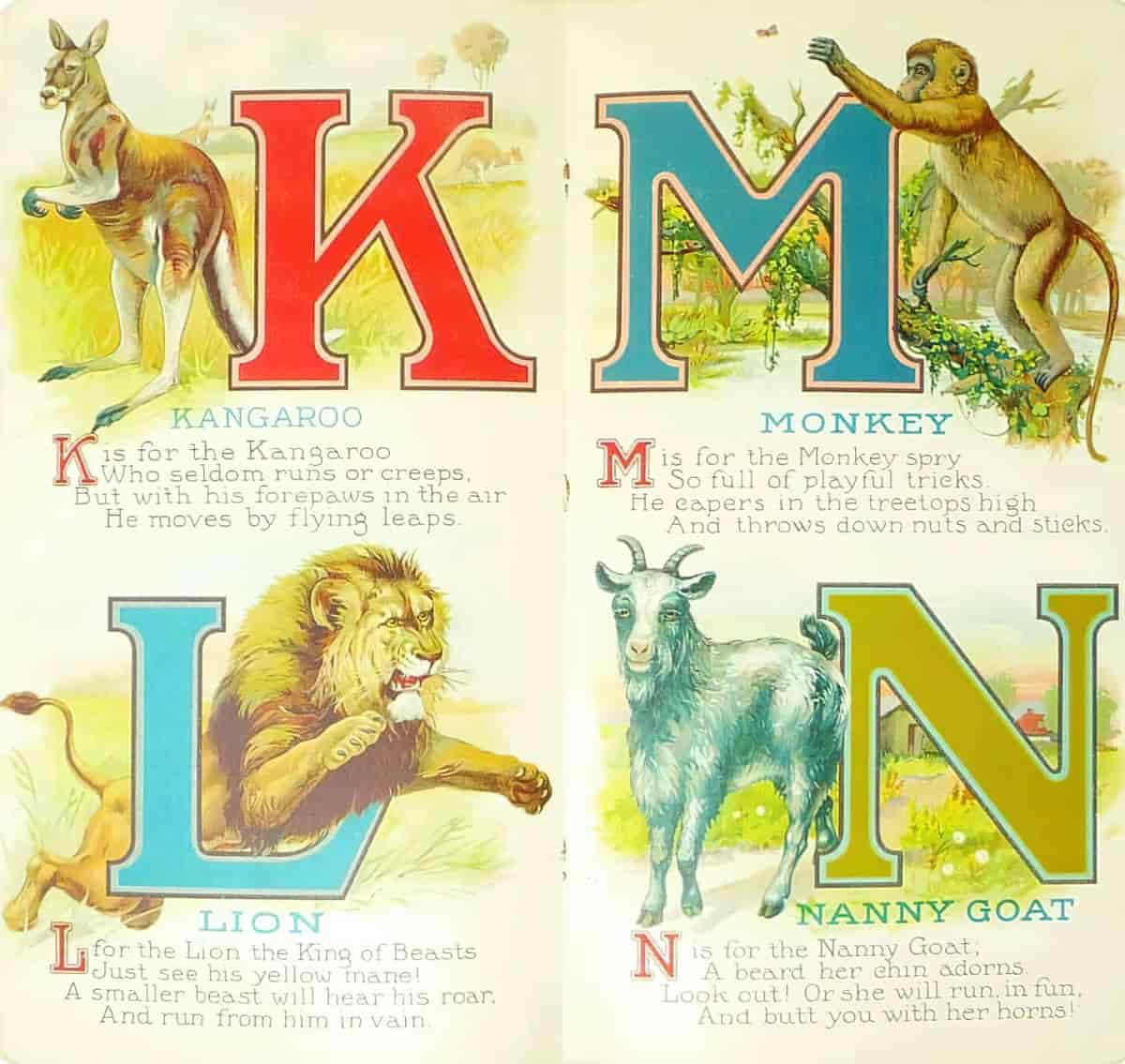

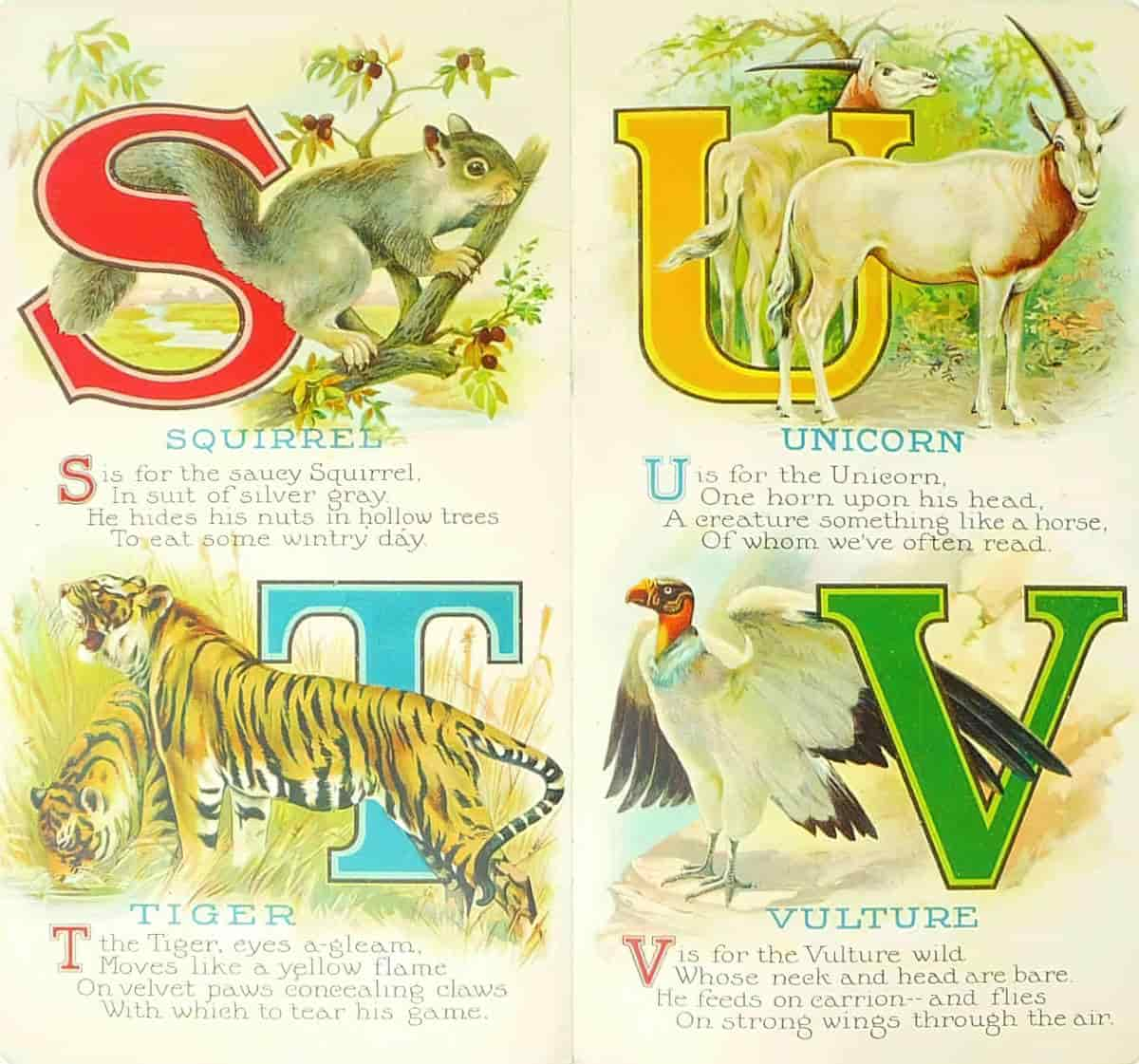

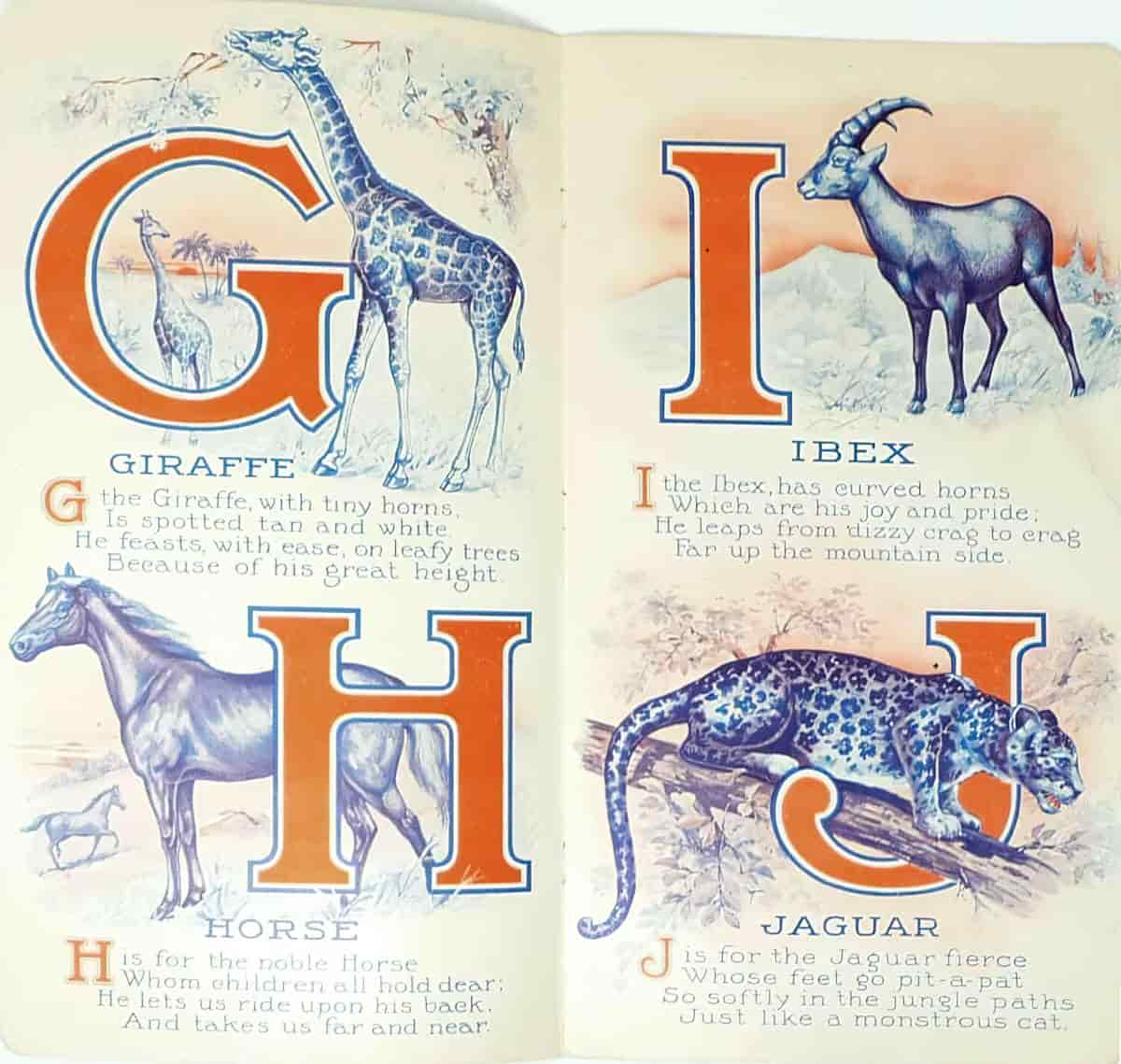

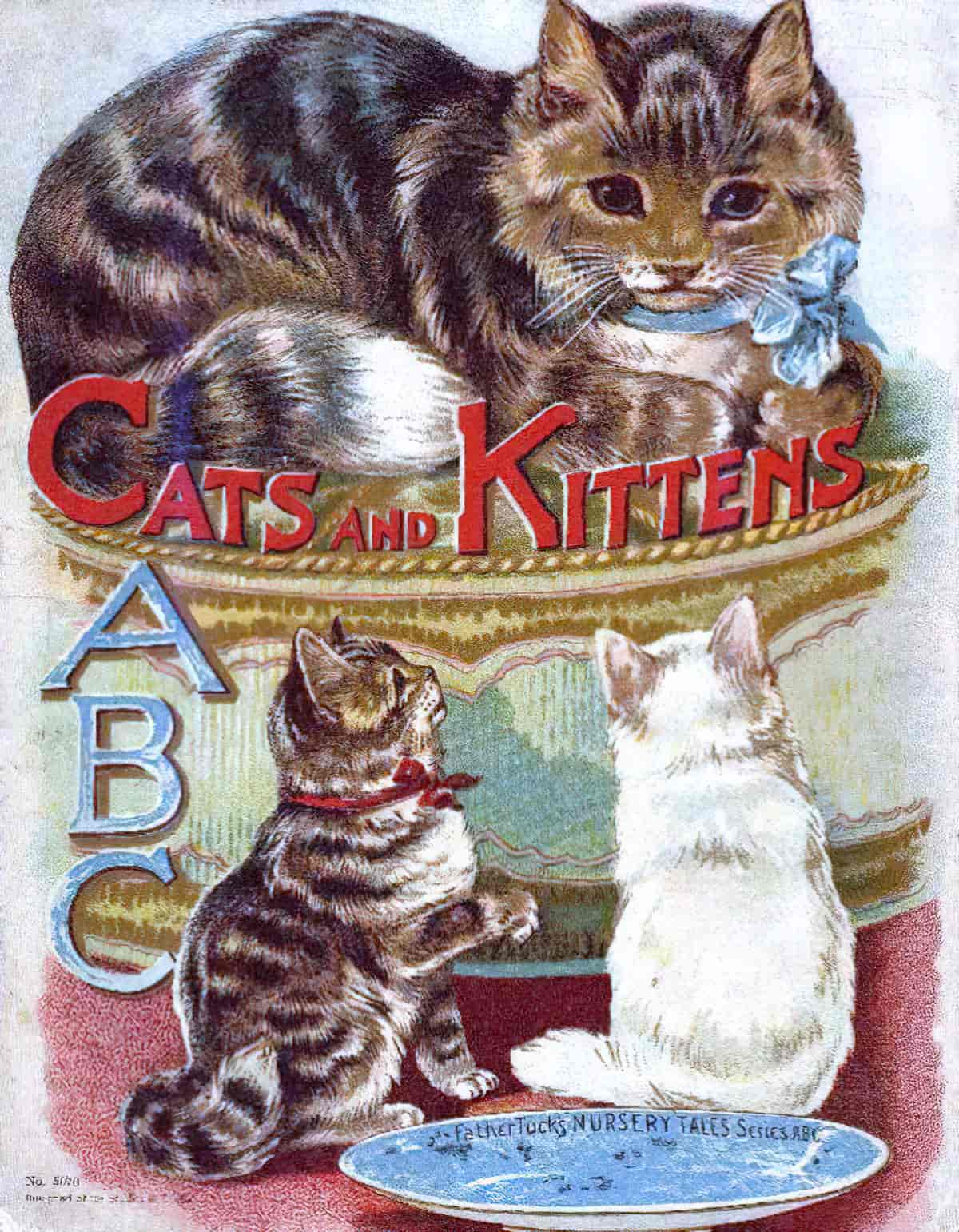

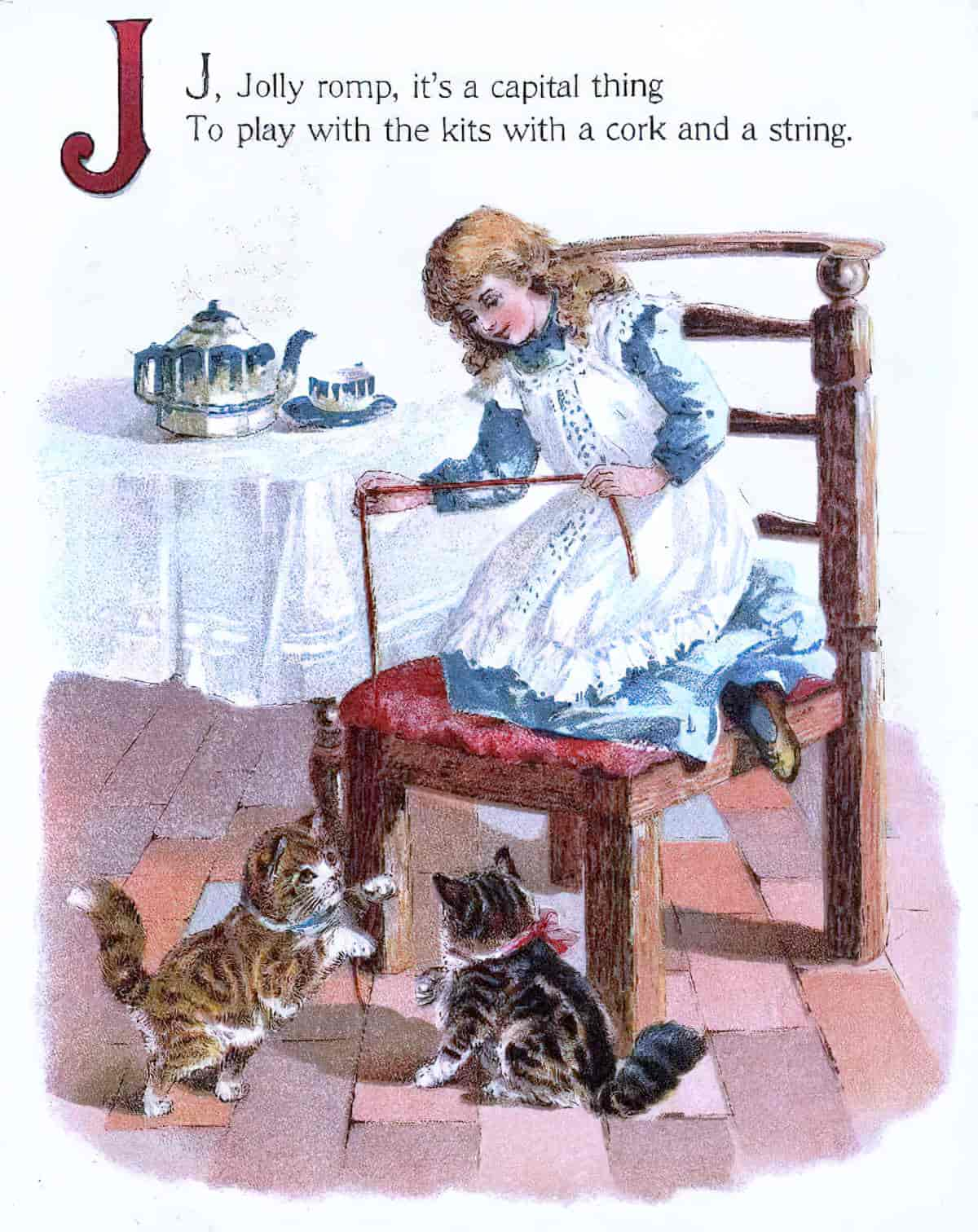

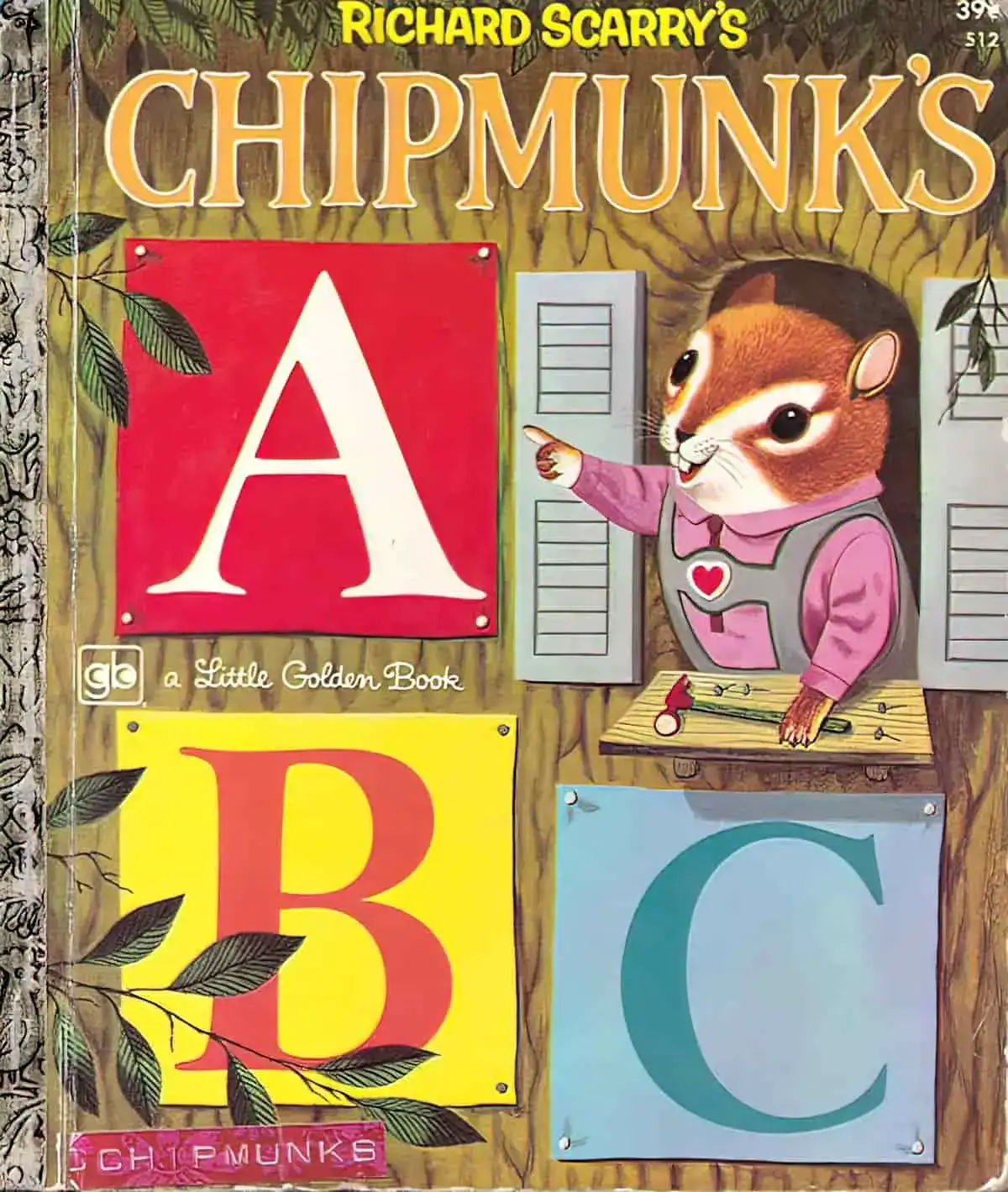

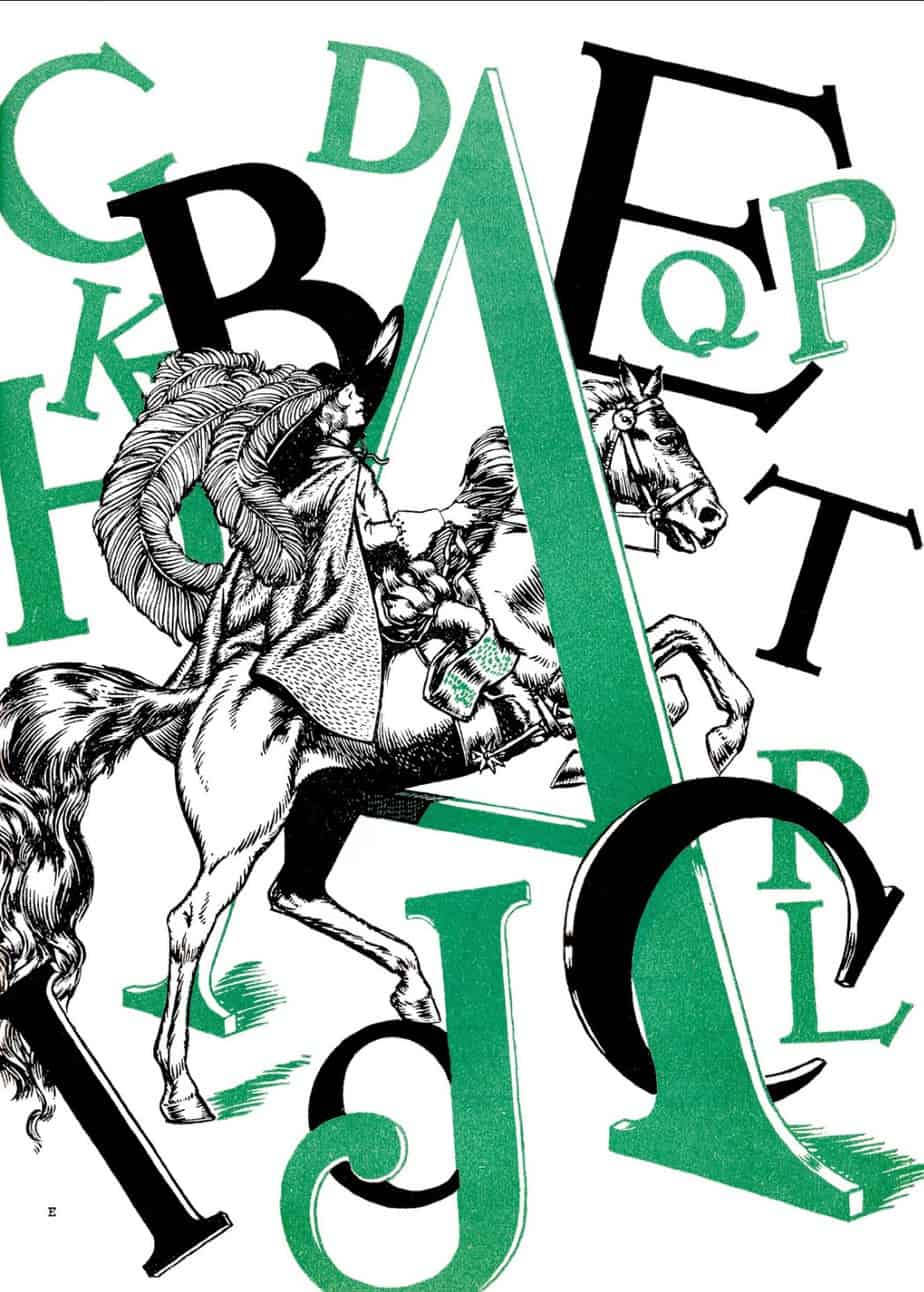

Abecedary

An ABC book, from Medieval Latin abecedarium (“alphabet, primer”).

Absurdism

when highly unlikely or impossible things happen it is called the absurd, most often used for comic effect. There is purposely no logic or continuity.

Abstract Expressionism

Art that while abstract is also expressive or emotional. Abstract expressionists were inspired by the surrealist idea that art should come from the unconscious mind.

Achrony

When the temporal deviation from the primary story cannot be placed in any given moment within the scope of the story. Rare outside purely experimental prose, but perhaps all pictures are achronical.

ADAPTATION

Retrospective adaptations reward audiences for any prior knowledge of the hypotext (or origin story). Retrospective adaptations offer a parallactic view of an older story.

Prospective adaptations can stand alone. Their relevance does not depend upon prior knowledge of earlier texts. Since the child readers of picturebooks have little life experience, when picturebooks come from adaptations, they are highly likely to be of this kind.

Aetonormative

Describes the phenomenon of setting adults up as the norm. Can be a problem in children’s literature, which is written by adults but meant to be read by children.

agogic

In music, pertaining to or emphasizing slight variations in rhythm for the sake of dynamic expression.

Allegory

a device in which characters or events represent or symbolise ideas and concepts. A message is communicated with symbols.

Allusion

(adj. allusory) An allusion is a reference to another story, for example an illustrator might include a girl in a red riding hood in a modern story, alluding to the classic fairy tale. Allusions are good for creating new dimensions.

Anachrony

chronological misplacement of any kind. (You probably know the word ‘anachronistic’.)

Analepsis

another word for a ‘flashback’ or ‘switchback’. A secondary narrative precedes the primary one. For example, a grandparently figure looks back in time. This might be expressed pictorially with a thought bubble, or sepia tones, or other recognised devices for expressing retrogression. The plural is analepses.

ANARCHY

Childhood according to Seuss is a perpetual zigzag between good sense and nonsense, between the anarchy of the Cat in the Hat and the selfless stoicism of Horton. They are like the ego and the id, not so much eternal antagonists as complementary poles. The books that he wrote, averaging one a year from the late 1930’s to the mid-1980’s, alternate between ever loopier (and sometimes forced) excursions into whimsy and ever more pointed (and sometimes forced) fables.

A.O. Scott, Sense and Nonsense, NYT Magazine

Antiphony

A poem or hymn which is divided into two parts. Each part responds to or echoes the other. [Much like words and pictures in a picturebook.] Antiphony: I Am The Great Sun

Backdrop Setting

(as opposed to integral setting) A setting exists, but it is separate from the story. The setting could be changed and the story would still exist, basically unchanged.

BOARD BOOK

A board book is a picture book printed on stiff board, designed to be used by toddlers who may damage books made of paper.

The humble board book, with its cardboard-thick pages, gently rounded corners and simple concepts for babies, was once designed to be chewed as much as read.

But today’s babies and toddlers are treated to board books that are miniature works of literary art: classics like “Romeo and Juliet,” “Sense and Sensibility” and “Les Misérables”; luxuriously produced counting primers with complex graphic elements; and even an “Art for Baby” book featuring images by the contemporary artists Damien Hirst and Paul Morrison.

A Library of Classics, Edited for the Teething Set, NYT

Callout

a call-out or callout is a short string of text connected by a line, arrow, or similar graphic to a feature of an illustration or technical drawing, and giving information about that feature (comic book speech bubbles)

CATCH TALE

The catch tale is a formulistic framework in which the manner of the telling forces the hearer to ask a particular question, to which the teller returns a ridiculous answer.

There’s a long history of catch tales in folk tale. See the CATCH TALES entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

Tall Tales can be used as Catch Tales.

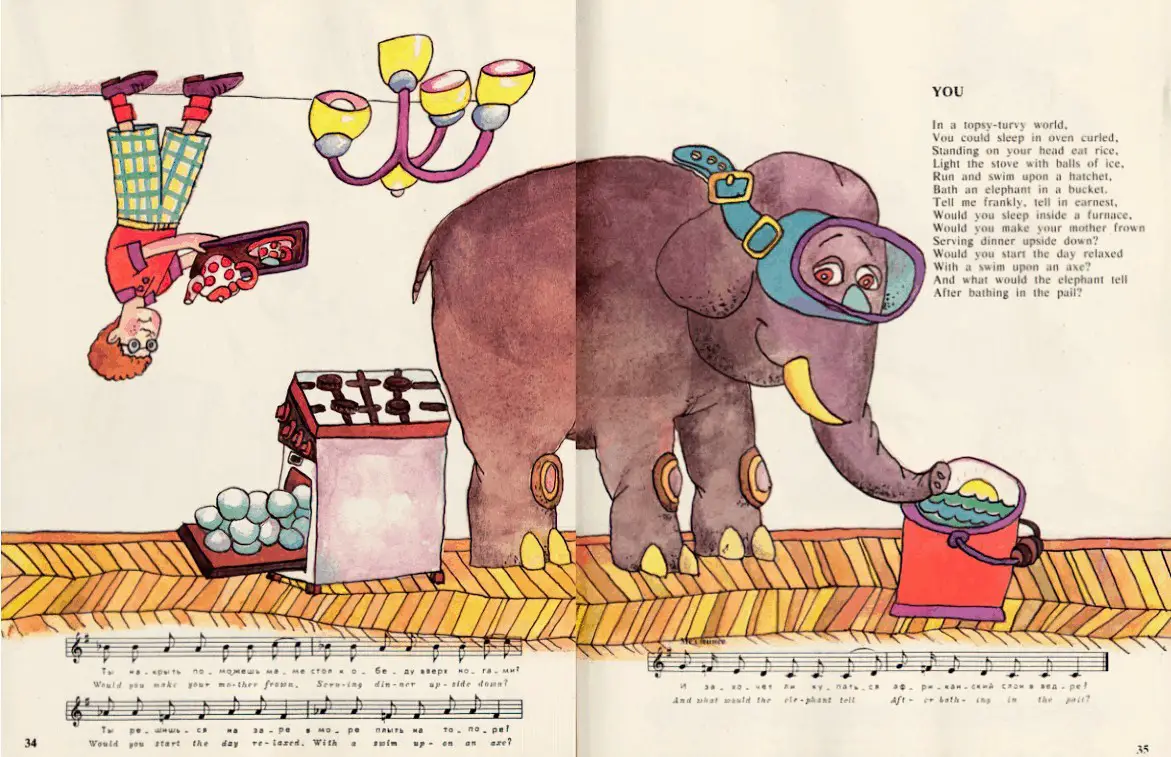

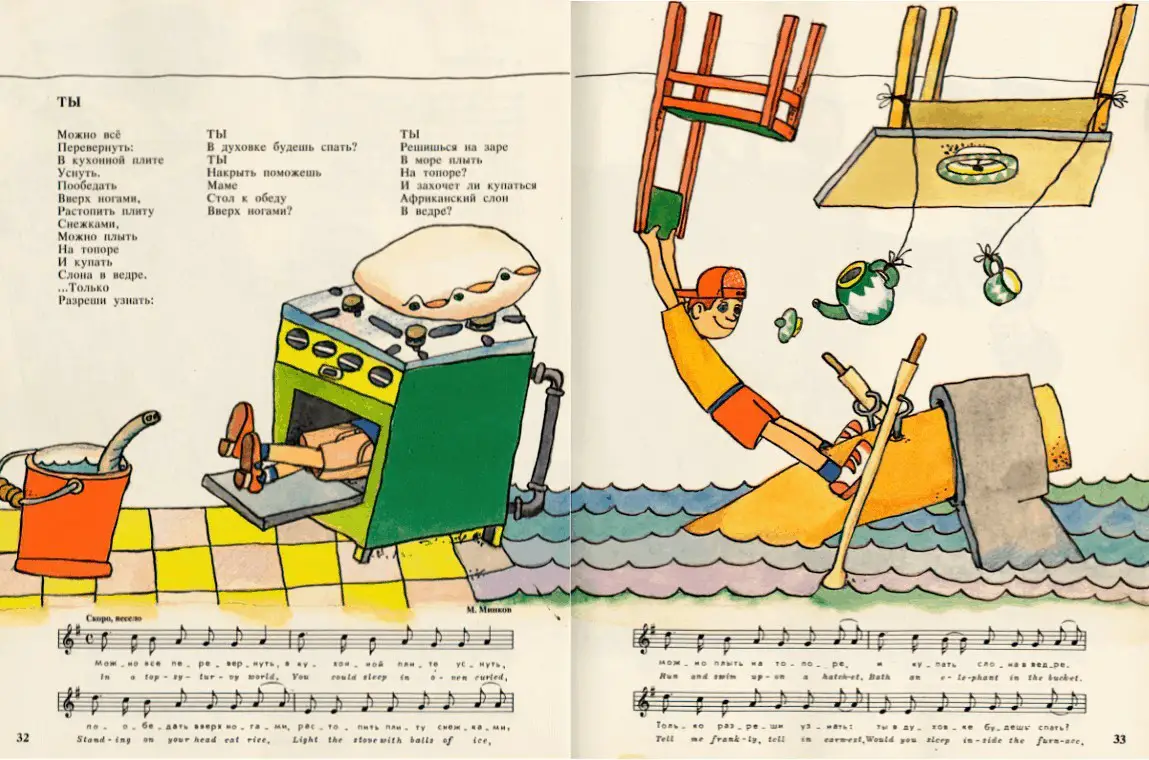

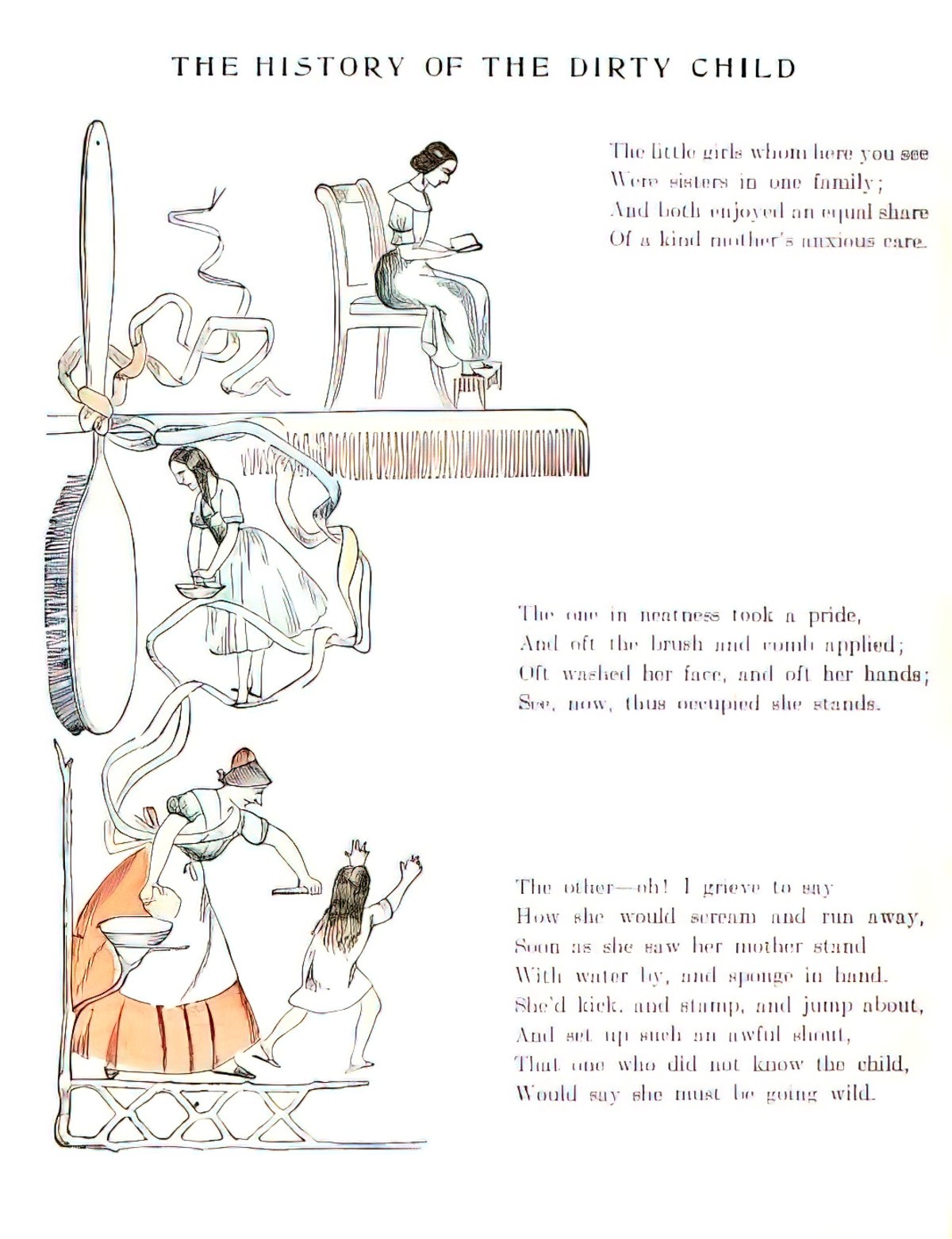

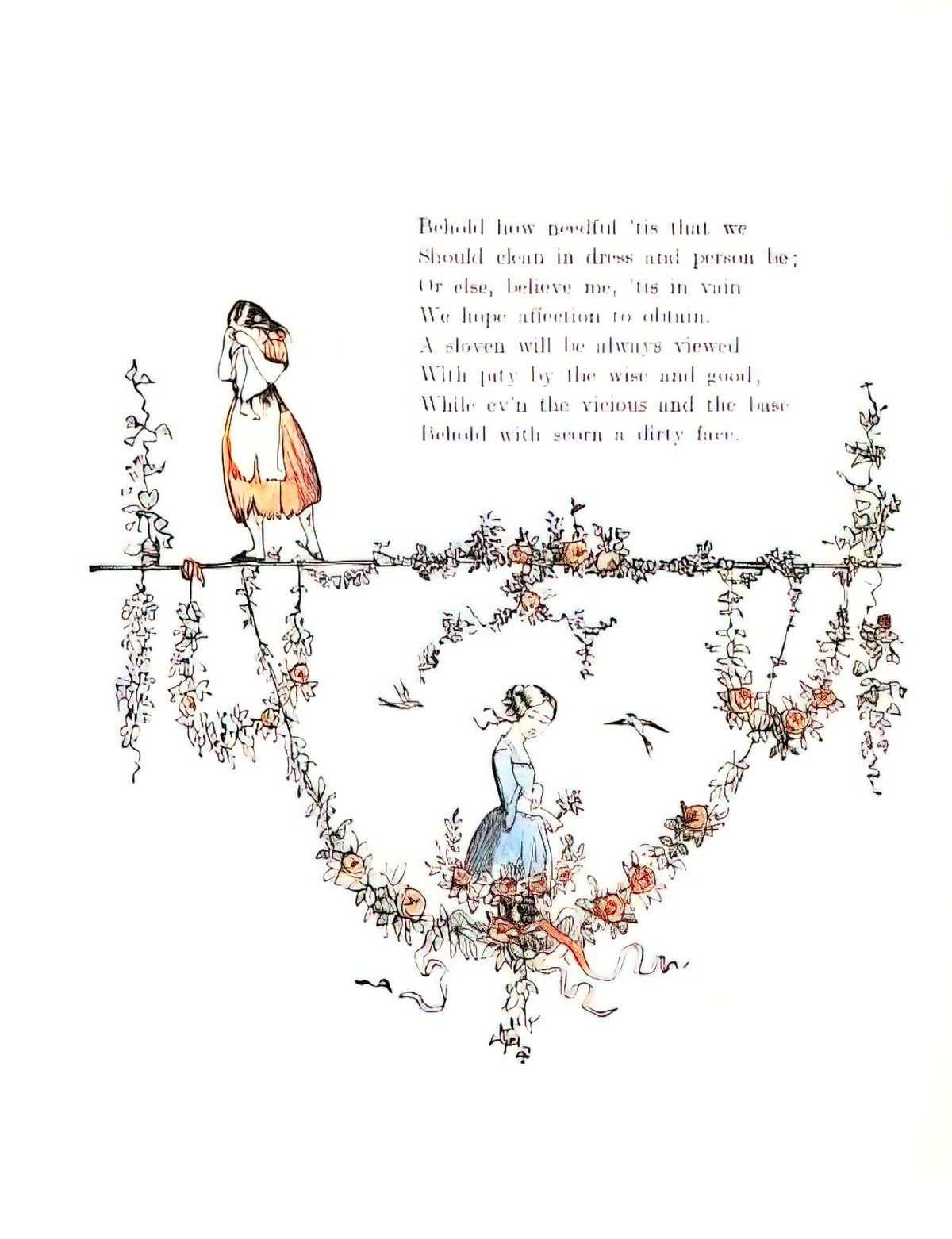

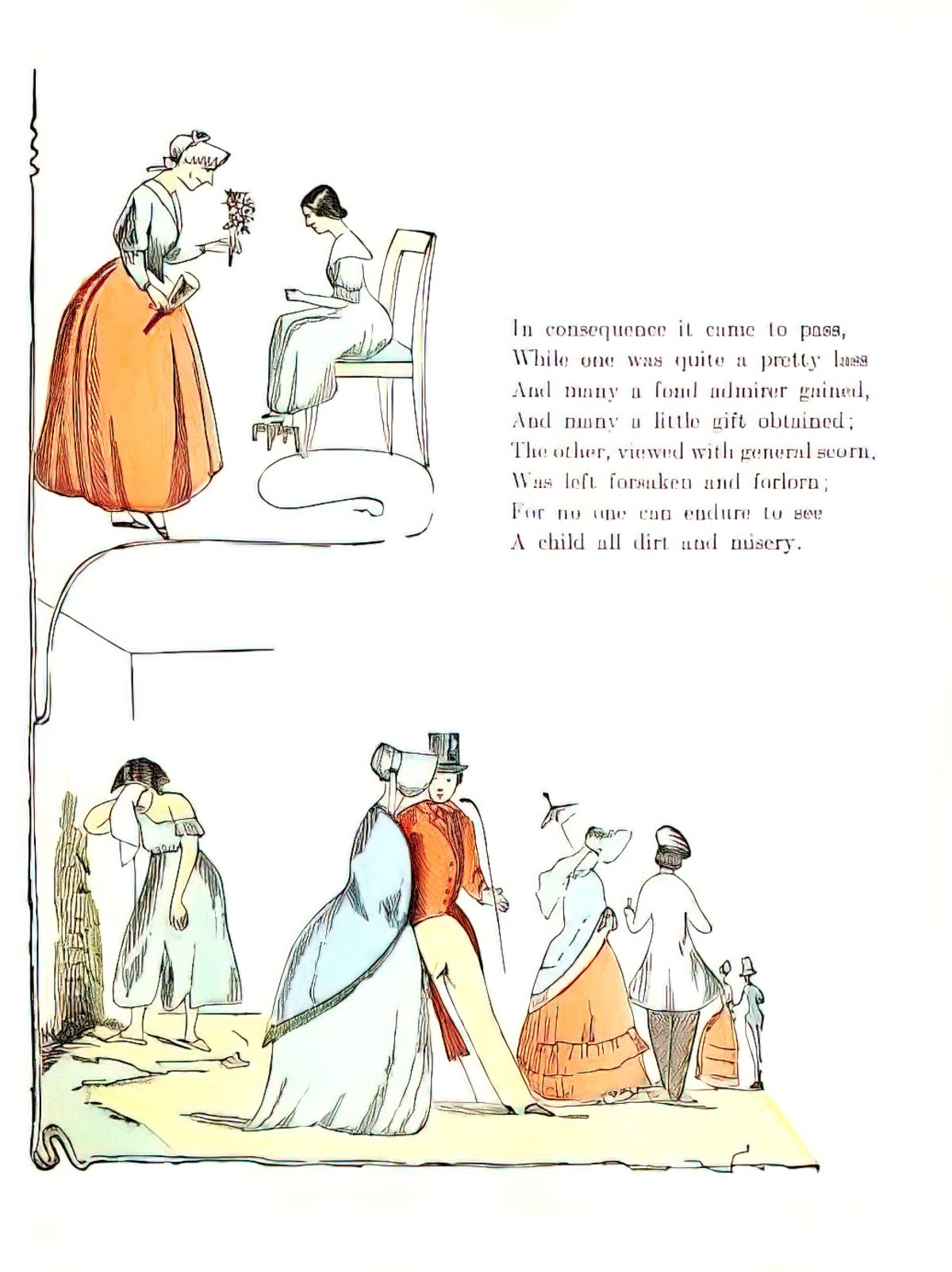

Cautionary tale

A tale told in folklore, to warn its hearer of a danger, e.g. in “Little Red Riding Hood” children are warned not to dilly-dally on the path and talk to strangers. Cautionary Tales are now outdated and more often satirised, for example by Hilaire Belloc in Cautionary Tales For Children.

DEICTIC

This is a linguistics term and refers to a word or expression whose meaning is dependent on the context in which it is used (such as here, you, me, that one there, or next Tuesday). When addressing a very young audience, certain words or expressions won’t be familiar to them due to life inexperience. This affects the vocabulary and situations storytellers use in stories for children, or affects how they are introduced (without the same presumption of prior knowledge).

Chronotope

the treatment of spatiality and temporality. A word to describe the way time and space are described by language, because time and space are impossible to depict via visual signs alone. Time can be indicated only by reference. In picturebooks time might be represented by changing light as the day fades, or with clocks and calendars or seasonal changes or ageing characters. But mostly in picturebooks, the passing of time is underscored by words. (Later, at ten o’clock that night, that afternoon, etc.)

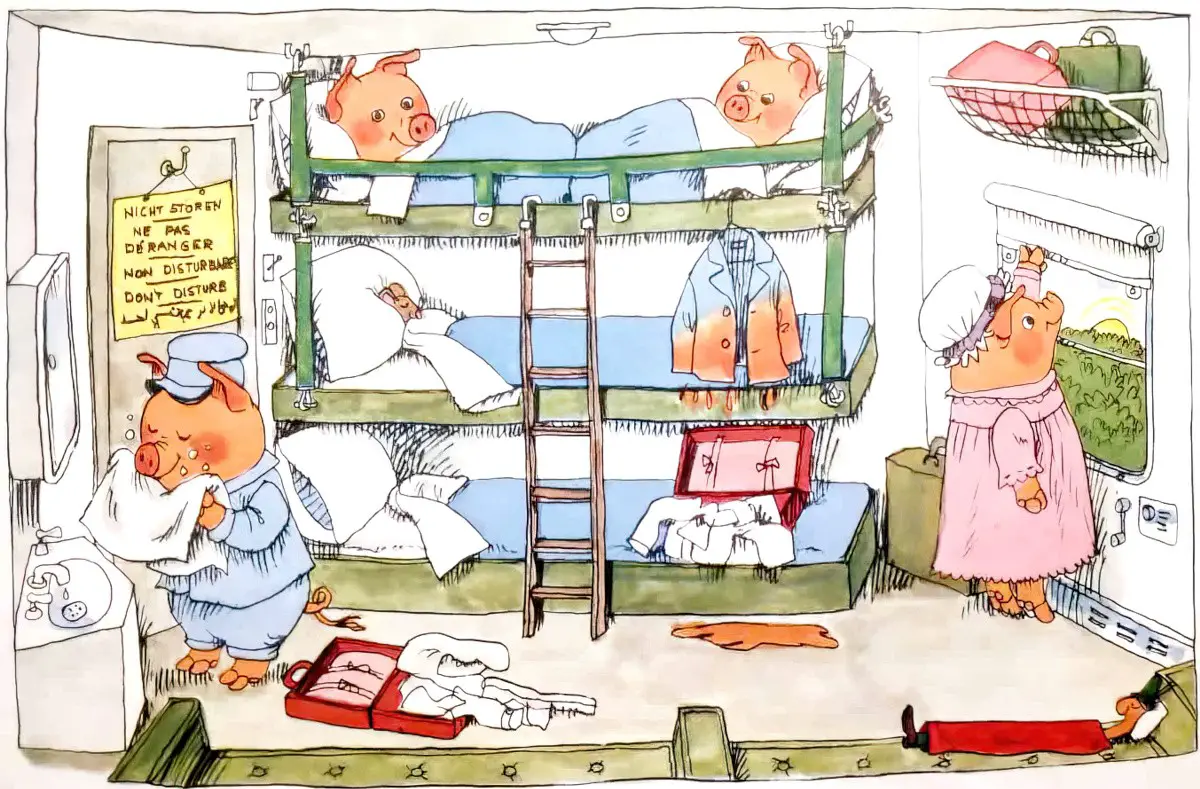

CINEMATIC (VS STAGE) PERSPECTIVE

Some illustrators work on a ‘stage’, while others are more ‘cinematic’, changing the camera around, including various angles and a mixture of close ups, medium shots and long shots.

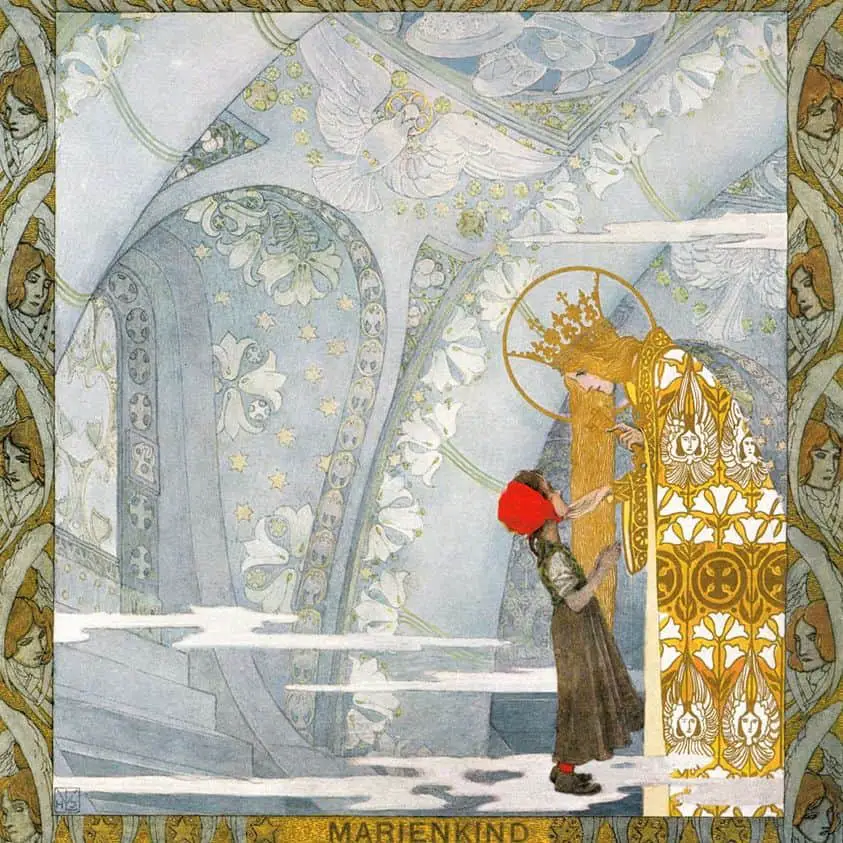

The illustration below is literally bordered by some stage curtains, and therefore makes for an excellent example of ‘stage’ perspective on the page.

Barbara Cooney is a good example of an illustrator who works with stage perspective. We seem to view scenes from the distance of a chair in the audience.

A picture book illustrator who works with cinematic perspective is Chris Van Allsburg. The proportion of cinematic picture books has increased over time. This is down to the influence of television.

Co-author, Co-illustrator or Co-narrator

Words for ‘users’ when the apps require participation (or the illusion of participation) in order to complete the story.

Interactive engagement on a creative level is, indeed, what most apps promise but seldom offer in a meaningful way.

COLONISATION

Why do children get different literature? Because adults think children are different. Childhood is ‘colonized’ by adults. (See article by Perry Nodelman: “The Other: Orientalism, Colonialism, and Children’s Literature.”.) This happens for two reasons: For education and for entertainment, to experience something vicariously. But we have this idea that kidlit must teach kids how to read and how to behave. Books can be too preachy or have lots of fun and these two things can have a tension in them. (Both of these two things do include a definition of a child.)

Colour Field Painting

Describes the work of abstract painters working in the 1950s and 1960s characterised by large areas of a more or less flat single colour

CONCRETIZATION

Texts often describe how places, people, or objects look or sound or smell. Readers can enrich their experience and increase their understanding by forming mental pictures: by imagining what is being described as exactly as the words of the text allow them to. This process is what theorists of reader-response call “concretization”. […] Concretization is a skill often possessed by children. In fact, imagining as literally and completely as possible the world and the people a text describes is the only way that many children know of building consistency from the texts they read. This seems to be the reason that so many children and other inexperienced readers worry about the logic and coherence of the worlds that texts enable them to concretize—why they so often get angry when there are inconsistent details in descriptions of places and people or confusions in the sequence of events.

On the other hand, concretization is a skill that many adults have forgetten. Many readers have been taught to focus so much on using texts’ potential for engendering sights and smells and sounds. That’s a pity. Not only does it deprive such readers of a source of pleasure, but it also prevents them from understanding the subtle richness of the texts they read.

The Pleasure of Children’s Literature by Perry Nodelman and Mavis Reimer

Continuous Narrative

Continuous narrative art gives clues, provided by the layout itself, about a sequence. Sequential narrative without the frames. Vignettes are often presented continuously, too.

Contradiction

On Nikolajeva and Scott’s scale of interanimation taxonomy we find ‘contradiction’, in which pictures and words do not match each other – one tells a different story from the other. This sort of picturebook demands more from the reader in terms of active synthesis, and may appeal to an older, more sophisticated audience, or to a dual audience, in which young readers understand one part of the story and the adult reader understands another. Of course, pictures and words can never be absolutely contradictory. It is a matter of degree. Stories with contradictory pictures and words are also called ‘twice-told tales’.

Contrapuntal

On Nikolajeva and Scott’s scale of interanimation taxonomy we find contrapuntal (the adjective form of ‘counterpoint’) This is a useful word when talking about words and illustrations which deviate from each other somewhat. Further along the scale comes ‘contradiction’, in which the pictures and words completely contradict each other.

Conventional Interaction

Unsurprising interaction in an interactive text, given what has come before. For example, the book app works like a digital version of a book, complete with ‘page turns’.

CUMULATIVE

There’s a long history of cumulative stories in folk tale. See the CUMULATIVE TALES entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

CYBERTEXT

As defined by Aarseth: The cybertext is, literally, “a machine for the production of variety of expression”. Aarseth’s textonomy of the cybertext can only partially be applied to book apps. For example, the aspect of “transiency” (meaning that in a transient text “the mere passing of the user’s time causes scriptons to appear” (Aarseth 1997, 63)) is not very helpful since virtually all book apps for children are intransient text. If a book app is played in the “read-to-me” mode (the closest thing to a transient text I have encountered in a children’s book app), the reading can usually be stopped and modes switched.

Degrees Of Interactivity

- selective participation, in which the user chooses among the options offered by the program

- transformative participation, in which the user selects and transforms the contents proposed by the author

- constructive participation, in which the user can select, transform and build new proposals that are not planned by the author

Dialogic

Relating to dialogue. When literacy researchers use this word they’re talking about how children and adults talk together about a book before, while and after reading.

DIDACTIC

Didactic refers to a story with a clear pedagogical purpose. “Moralistic”.

Everything has a moral, if only you can find it.

Lewis Carroll, Alice In Wonderland

Adults often assume that all children’s stories are fables or should be read as fables […] Aesop’s fables usually end with an explicit statement of a moral. But these stories have been retold by many people, and Joanne Lynn points out that “those who retell the fables always manage to find ‘morals’ that mirror their own values”. When the printer Caxton first published the fables in English in the fifteenth century, he said that the story of the fox and the grapes showed that the fox was wise not to want what he couldn’t have.

In more recent versions the fox’s behaviour is neither wise nor admirable but shallowly self-deceptive; the moral is something like “It’s easy to despise what we can’t have” It seems that, if readers assume a story is a parable or a fable, the presence of a moral is so important that almost any one will do.

Anyone who expects a moral or a message is sure to find one. That this is the case reveals the degree to which messages or themes are separate from the texts readers relate them to. In seeking messages, readers tend to confirm their own preconceived ideas and values: to take ideas from outside the text and assume that they are inside it. That prevents them from becoming conscious of ideas and values different from their own.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

Each reader has to find her or his own message within a book.

Laurie Halse Anderson

Diegetic

Communicates by telling. The flipside of mimetic. In a film, a soundtrack is ‘diegetic’ if it occurs naturally as part of the story, such as in the films of Quentin Tarantino, or on the TV series The Wire, in which any music must come from a radio, or from a CD that a character is playing in the background, rather than added later as part of the editing process. In picture books, verbal text is diegetic.

A phrase such as ‘the diegetic real’ is useful when making a distinction between what is meant to be understood as realism versus what is meant to be understood as ‘happening within the child’s imagination’.

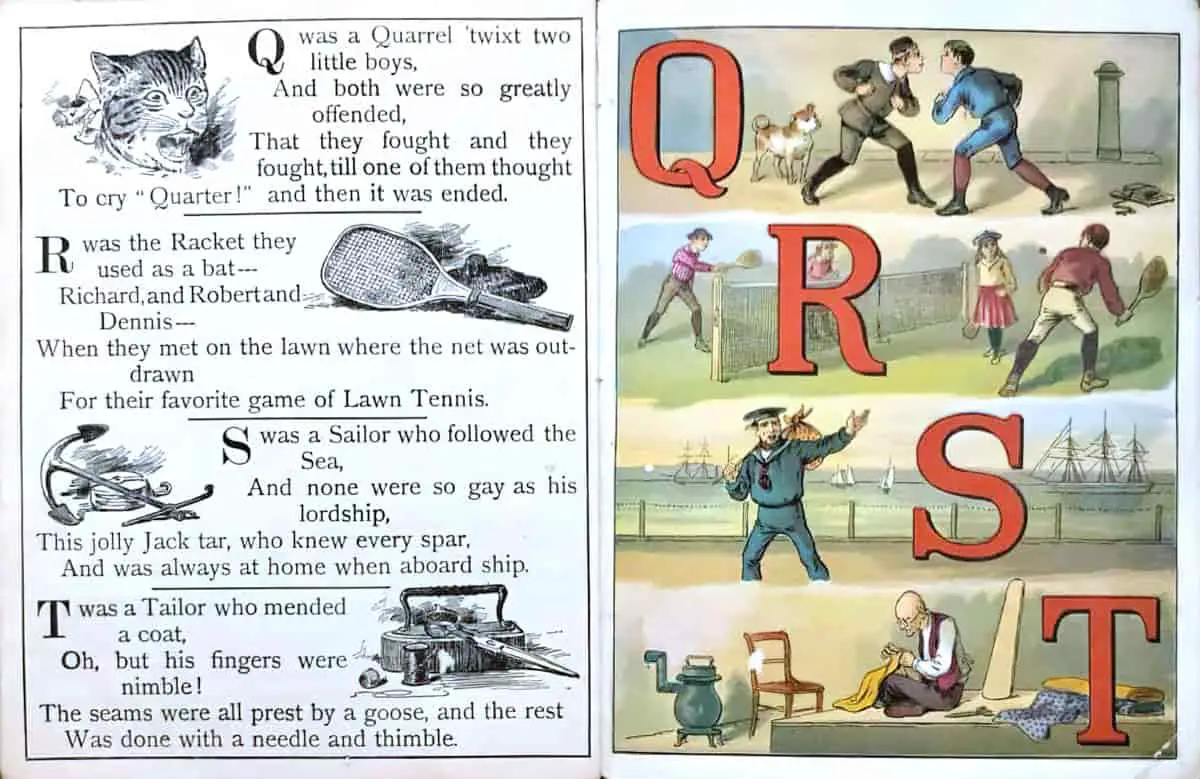

DOGGEREL

Doggerel refers to comic verse composed in irregular rhythm. Bemelmans’ Madeline series is considered ‘doggerel’. The word also describes verse which is simply badly written.

Double Address

When an author intends adults to get things out of a story that children would not. (See also: single address). Some commentators have called the middle grade version of this The Mark Twain Wink, as he was well-known for it. E.B. White and A.A. Milne also used this technique. Note that all of these men also wrote for adults.

Doublespread

a graphic/illustration spreads across two open pages

Droodle

“Droodle” is a nonsense word suggesting “doodle”, “drawing” and “riddle.” Their general form is minimal: a square box containing a few abstract pictorial elements with a caption (or several) giving a humorous explanation of the picture’s subject. For example, a Droodle depicting three concentric shapes — little circle, medium circle, big square — might have the caption “Aerial view of a cowboy in a Port-a-john.”

Dual audience

A ‘children’s book which appeals to both children and adults. Big budget stories (e.g. Pixar movies) are expected to appeal to both children and adults.

Picture books are synonymous with Children’s Literature. But is this is a necessary condition of the art form itself? Or is it just a cultural convention, more to do with existing expectations, marketing prejudices and literary discourse?

from an essay by Shaun Tan

With their violent excesses and winning magic, fairy tales once entertained adults and children together. As John Updike said, they were the television and pornography of an earlier age, and they rarely pulled punches, even when the young were listening in.

Maria Tatar, NYT

‘Children’s books’ in general must appeal to adult co-readers as much as to the child. Picture books in particular must have a ‘dual audience’.

What does this mean, exactly? It can mean one of two things:

- The material must be so universal that it transcends age.

- The story must operate on more than one level, with some things understood only by the adult co-readers.

Ecology

Used primarily for the life sciences, this term has also been employed by sociolinguists and psychologists to describe the ways in which organisms interact with environment. The term ‘ecology’ might also come in handy for discussing picturebooks, and the ways in which words interanimate with pictures. The term ‘ecology’ may be especially appropriate because the ways in which words and pictures feed off each other are different from book to book and even from page to page. One moment words can step forward to occupy centre stage; next moment they return to the wings or comment like a chorus on some key point of action. Ecology is far more dynamic than any kind of taxonomy.

Emergent reader

describes readers who have not yet achieved fluency, and who may need a slightly different kind of picturebook from fluent readers

Enhancement

On Nikolajeva and Scott’s taxonomy of interanimation we have ‘enhancement’ somewhere in the middle, in which the pictures enhance the words without being contradictory. Agosto calls this ‘augmentation’.

ENDLESS TALES

An endless tale is a formulistic framework for a narrative. In these tales, the wording of the tale is arranged so as to continue indefinitely.

There’s a long history of endless stories in folk tale. See the ENDLESS TALES entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

ENDPAPERS

Also called end pages. Peritextual parts of a hardback picturebook found on the flipside of the back and front of the cover. Endpapers have been a part of bookbinding since the mid 1600s. We have front endpapers and back endpapers. These pages are the first parts of the interior of the book seen when the book is opened, and the last to be seen after the story has been read and the book is about to be closed.

EPITEXT

Gerard Ganette’s word for the creations that exist around an author’s work: interviews, publicity announcements, reviews by and addresses to critics, private letters and other authorial and editorial discussions. These exist ‘outside’ of the text in question but still influence how an audience will come to a work, and their reading of it.

ERGODIC LITERATURE

As defined by Aarseth: Cybertexts are part of “ergodic literature,” that is, literature in which “nontrivial effort is required to allow the reader to traverse the text”. The keyword in defining a text as ergodic is, of course, “nontrivial” which is vague enough. While swiping and tapping to navigate from one screen to another can clearly be defined as “trivial” (much like turning a page), gestures like tapping on a hotspot to trigger an animation should be regarded as alterations of the text, namely the story, and can thus not be qualified as trivial.

Extraliterary Experiences

The real-world experiences readers bring to the page, and that author/illustrators can assume of readers. For example, children know that some children go to school on a school bus, so this basic concept need not be explained.

FABULA

In contradistinction to ‘story’: Fabula refers to “a series of logically and chronologically related events that are caused or experienced by actors”—thus answering the question “what happens?”—the term story indicates “a fabula that is presented in a certain manner” (answering the question “how is it told?”) In other words: “discourse for the analysis of hypertexts”

In relation to picturebook apps:

multiple fabula apps = in which user follows the concepts of “creating your own story” or “choosing your own adventure.” This type of app is most strongly affiliated with gaming and role-playing, sometimes to the extent that border lines become blurred. users can determine (to a certain extent) what happens in the narration. To evaluate multiple fabula apps, it is useful to consider the actual purpose of this narrative device. Is it to create a random text out of random fragments or is it to encourage users to explore narrative modes ? Does it give the user the opportunity to alter the fabula to produce aesthetically satisfying narratives that have been noticeably affected by the user in a purposeful way? Is randomness the result of the app’s mechanization or an aesthetic failure?

contrasted with:

alternative story apps = Basically, all apps that offer some kind of tap-triggered dialogue, sound or animation fall into this category.

Fairy painting

a genre of painting and illustration featuring fairies and fairy tale settings, often with extreme attention to detail. Fairy painting was popular in the Victorian era and made a comeback in the 1970s.

FIRST PERSON POINT OF VIEW

Remember that illustrations as well as textual narration can be described in terms of first (and third) person.

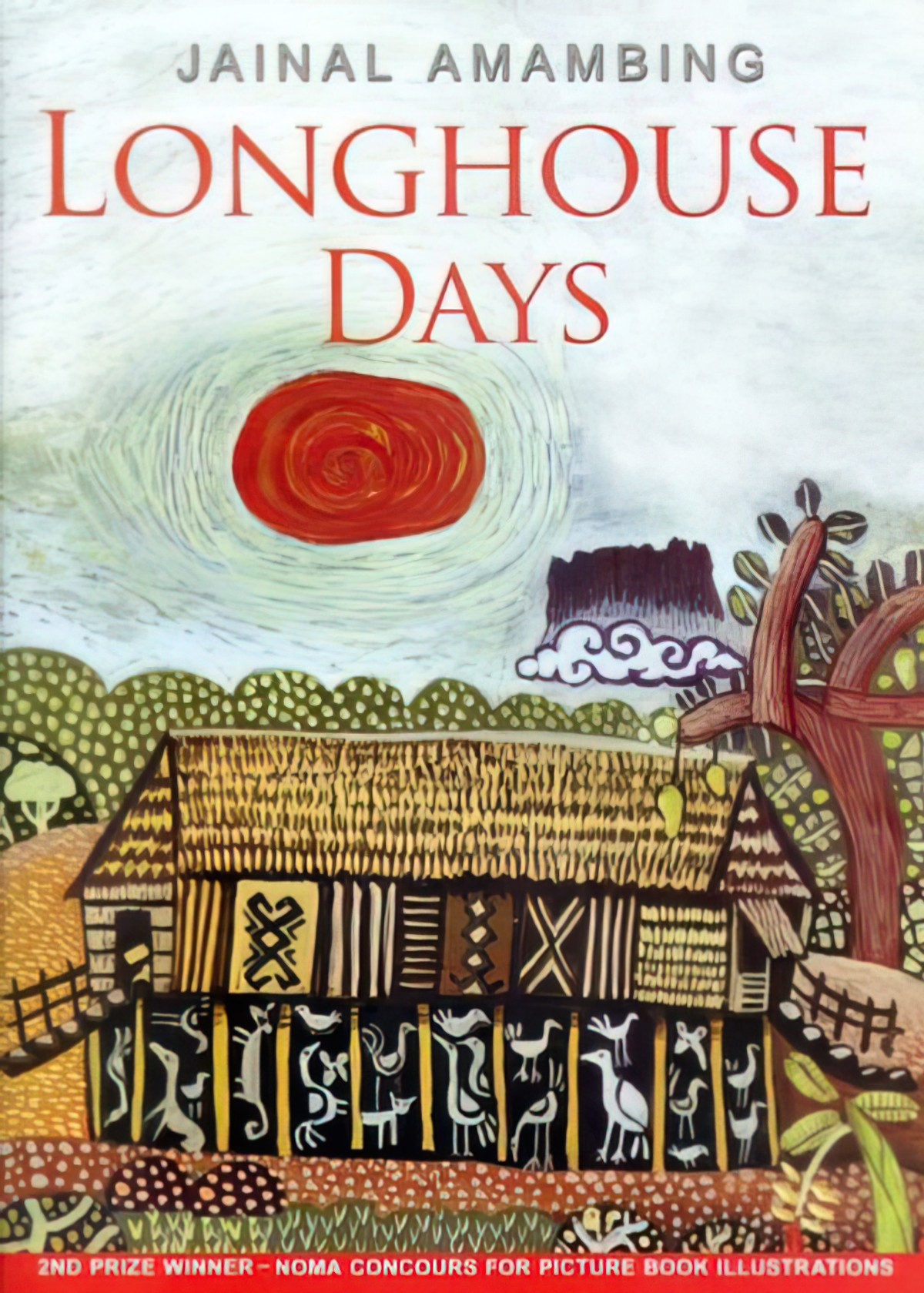

FOLK ART

Art which borrows elements or techniques from art done by the people (rather than by formally trained painters). Folk art tends to be decorative and the perspective off-kilter or flattened. Rosie’s Walk is a good example of folk art in a picture book.

FORMULISTIC CONVERSATIONS (FORMULAIC)

An example of a formulaic conversation from Little Red Riding Hood:

“Grandmama, why are your ears so big?”

“All the better to hear you with, my dear.”

There’s a long history of formulaic conversations in folk tale. See the FORMULISTIC CONVERSATIONS entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

Funny animal

Funny animal is a cartooning term for the genre of comics and animated cartoons in which the main characters are humanoid or talking animals, with anthropomorphic personality traits. The characters themselves may also be called funny animals.

Graphic poetry

A category including acrostics, calligrams, concrete poetry and other kinds of visual poems. Also called ‘shape poems’.

Hedcut

A term referring to a style of drawing, associated with The Wall Street Journal half-column portrait illustrations. They use the stipple method of many small dots and the hatching method of small lines to create an image, and are designed to emulate the look of woodcuts from old-style newspapers, and engravings on certificates and currency.

HETEROGLOSSIA

Multiple voices. A diversity of voices, styles of discourse, or points of view in a literary work. Postmodern picture book authors like Wanda Gag and A.A. Milne utilised the space of children’s literature to play around with the interrelationship between words and images.

The term was introduced by the Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin in his “Discourse in the Novel” (1934). Adjective: heteroglossic.

He was talking about the presence of two or more expressed viewpoints in a text or other artistic work. In a novel, you might have the voice of the characters (dialogue) and the voice of the unseen narrator. These are two different voices, at least. We all speak differently to our friends, children, partners and work associates. This is heteroglossia.

Bakhtin was saying there is no such thing as a single, solitary language which exists in a linguistic, literary, or existential vacuum, untouched and unaffected.

Even young children do this. When they play, children appropriate social roles and rules in pretend scenarios and use a variety of ‘voices’ in role enactment.

During the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature, picture book creators such as Wanda Gag and A.A. Milne were experimenting with children’s experience of heteroglossia. These authors were part of the Modernist art movement. One of the standout features of Modernism: The idea that there’s no such thing as a single, veridical truth. Everything depends on your viewpoint and where you happen to be standing.

Postmodern picture books continue to explore our heteroglossic human experience. A stand-out example is Voices In The Park by Anthony Browne.

Related word: Polyphony (multiple voices). This is another of Bakhtin’s words. He came up with polyphony before he came up with heteroglossia. The two words are now basically the same. If there’s a difference, it’s this, laid out by Morson and Emerson (1990): Heteroglossia describes the diversity of speech styles in a language while polyphony is to do with the position of the author in a text.

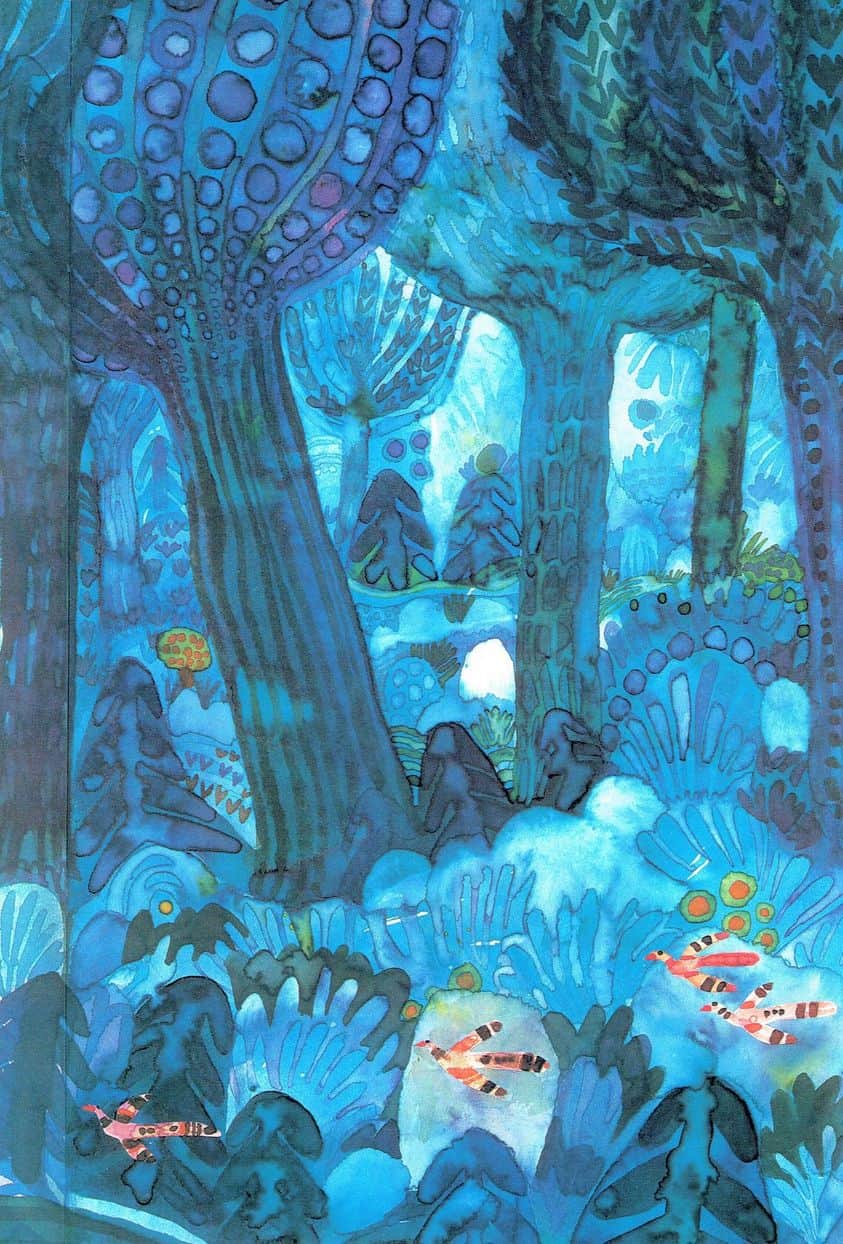

HIGH CHROMA

Chroma is another word for ‘saturation’ and describes the departure degree of a color from the neutral color of the same value.

Colors of low chroma are sometimes called “weak”. High chroma images (as shown below) are also called “highly saturated,” “strong,” or “vivid.”

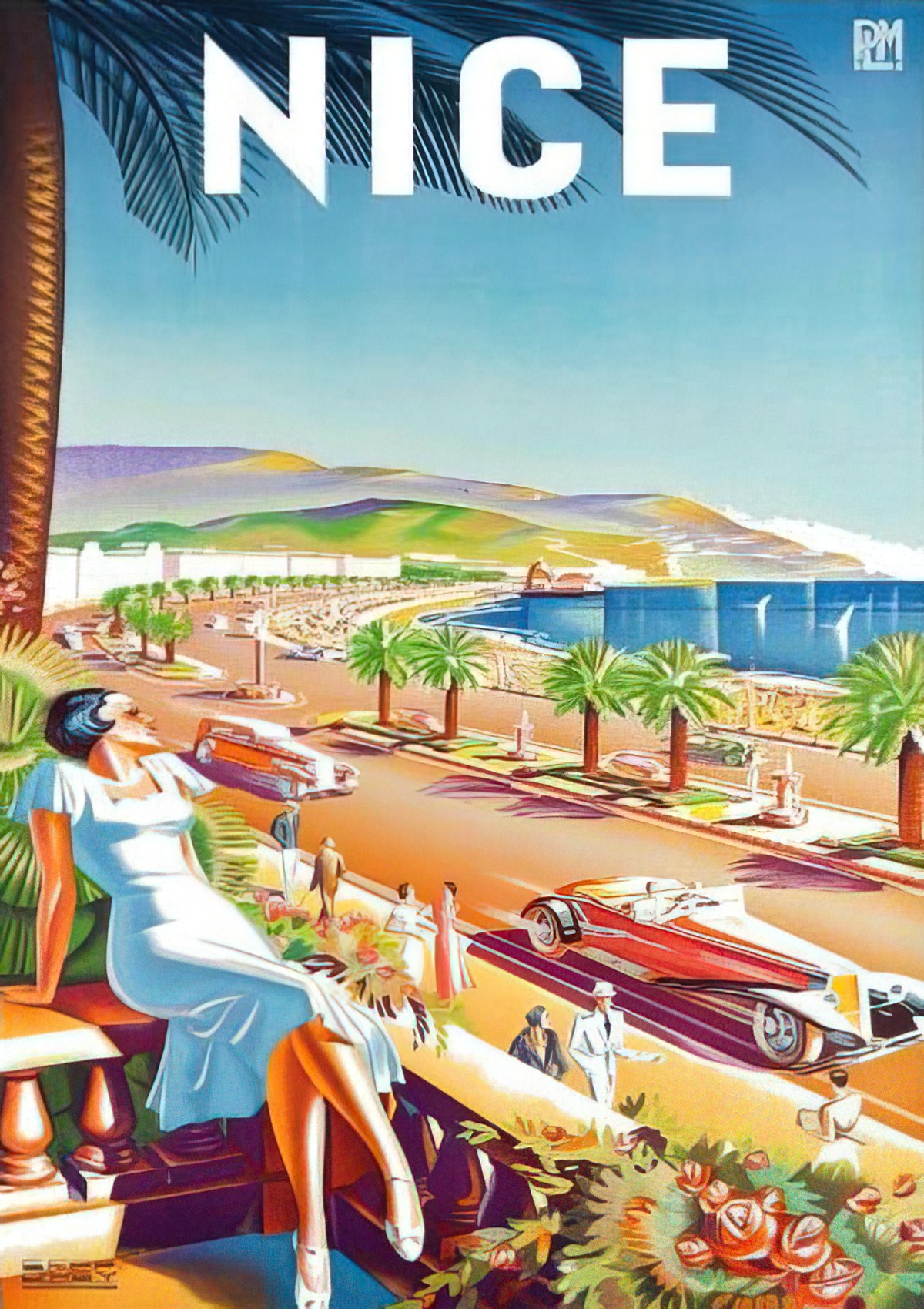

High chroma art can sometimes lend an atmosphere out of the first half of the 20th century.

HIGH KEY

High key images comprise a range of light value colors. (At the other end, a low key scheme contains a range of dark value colors.) More specifically, high key color describes the set of colors that range from mid-tone hues to white, while low key color spans the range from mid-tone to black.

In photography, high-key lighting results in brightly lit subjects with more fill light and softer shadows. Low-key is a photography term, but the art world had had its own word for ages: chiaroscuro. Technically, chiaroscuro is when an artist uses a high contrast between light and dark with the effect of creating a dramatic mood and also to draw the viewer’s eye to a particular part of the composition.

Basically, high key equals lighter. Low key equals darker, and probably with more shadows.

A picture book sometimes goes from one key to another over the course of the story, matching the main character’s mood.

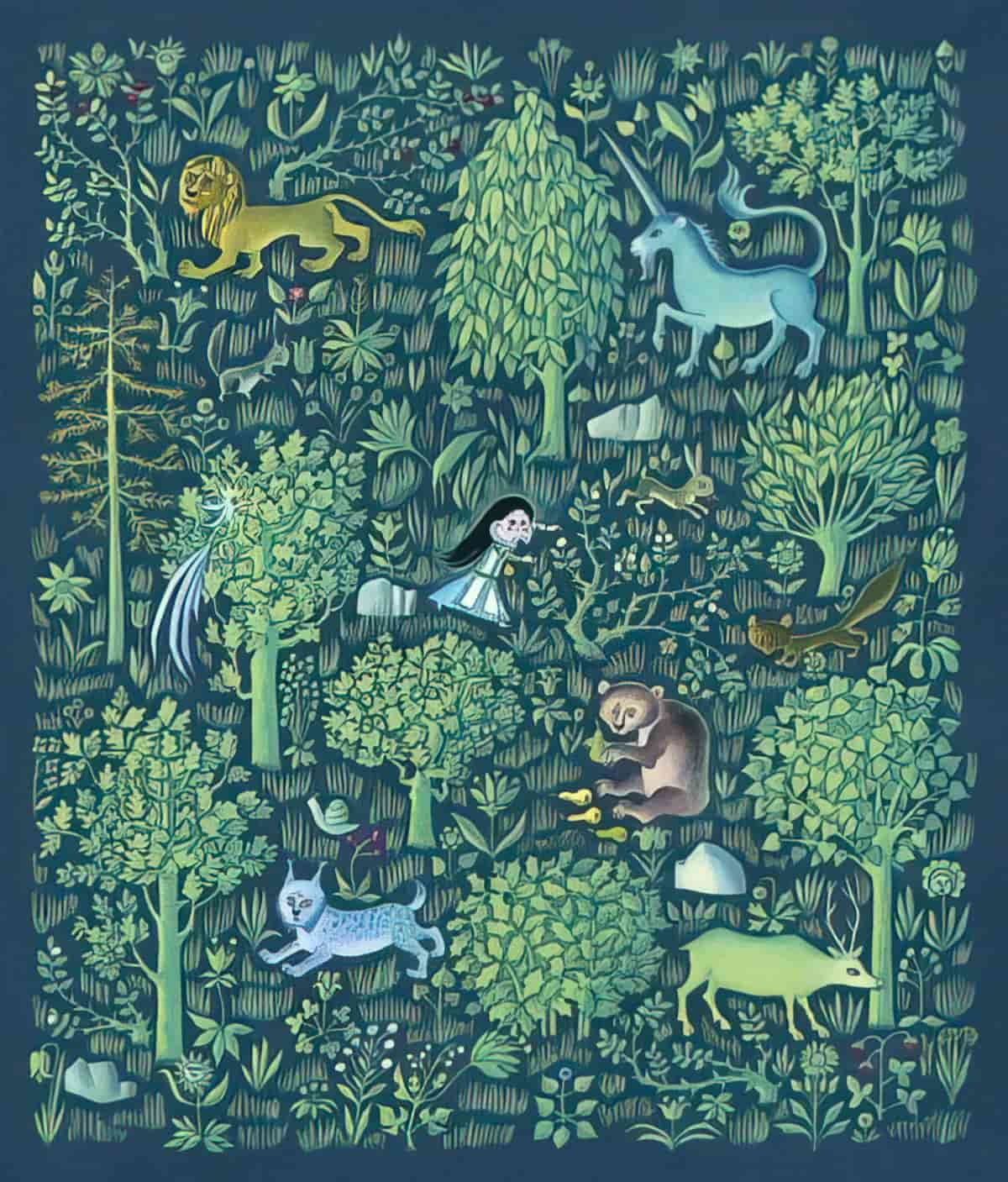

Horror vacui

In visual art, horror vacui (Latin for ‘fear of empty space’) or kenophobia (from Greek for ‘fear of the empty’) is the filling of the entire surface of a space or an artwork with detail. In physics, horror vacui reflects Aristotle’s idea that “nature abhors an empty space.”

Italian art critic and scholar Mario Praz used this term to describe the excessive use of ornament in design during the Victorian age.

If something is so detailed it almost makes your brain hurt, you might describe it as horror vacui.

Hotspot

In a book app, a part of the screen which initiates an action when touched. The effect is said to be ‘tap-triggered’.

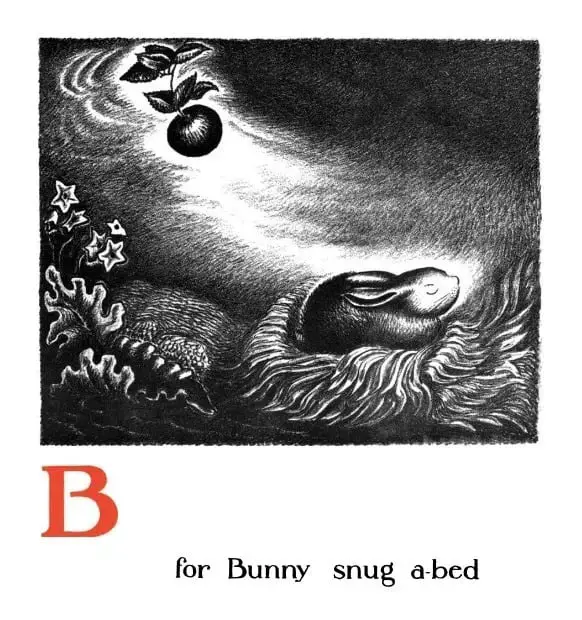

HYGGE

Hygge, meaning ‘snug’; is a Scandinavian concept that evokes “coziness”, particularly when relaxing with good friends or loved ones and while enjoying good food.

This word also describes a large number of picture books — those which aim to create a snug and cosy atmosphere for readers.

HYPERTELY

An extreme degree of imitative coloration or ornamentation not explainable on the ground of utility. (Adjective: hypertelic.)

Hypertext

The relationship between a given text (the ‘hypertext’) and an anterior text (the hypotext) that it transforms e.g. Snow White in New York is the hypertext of Snow White the traditional fairytale (the hypotext). This word relates to diegetic levels.

The concept of cybertext is neither limited to nor does it include all kinds of literary texts published in the digital medium. Hypertexts, on the other hand, are a specific type of fiction within this medium that is distinguished by certain technical characteristics, that is, “a text that […] will ‘branch or perform on request’ (by links or other means)” (Wardrip-Fruin 2010, 40). Even a cursory glance at children’s book apps reveals that only a limited number of them fall into either category. Therefore, a different framework must be used to assess this kind of media.

Iconotext

A genre in which neither image nor text is free from the other. A term (first?) used by Richard Wagner, who wrote the book Reading Iconotexts: From Swift To The French Revolution. Author/illustrator Jon Klassen discusses this ‘middle space’ between illustration and writing which the reader must fill for themselves, creating a much more expansive world than either the illustrations or words could achieve by themselves. The process in which the reader interacts with an iconotext and fills in the gaps is called interanimation.

Iconophor

An artform around a letter of the alphabet. Its origins lie in medieval illuminations, though the abecedarian connection was usually coincidental in the Middle Ages.

Illustrated fiction

A broad term encompassing not only picturebooks but also comics, graphic novels, illustrated magazine fiction and anything else in which words and picture work together to tell a story.

Illustrations do have a narrative purpose. They must show us not just beautiful patterns and evocative atmospheres but what people look like as stories happen to them; that is, as they move and talk and think and feel. So their faces and bodies usually have the simplicity, and consequently the expressiveness, of cartooning, a simplicity at variance from the frequent richness and detailed accuracy of their backgrounds, which give us a different sort of narrative information. When faces and bodies do have the same solidity and detail of shading and lines as their backgrounds, they may come to seem static and inexpressive…The extraordinary expressiveness of cartooning seems to make it a particularly appropriate means of communicating narrative information. To suggest that all picture-bo0k art is a sort of cartoon or caricature is no insult; it merely stresses the extent to which the purposes and pleasures of this art differ from those we assume of other kinds of visual art.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures:

Impressionism

A movement in art which can be seen in some picture books. Impressionistic paintings make it seem as if the viewer only caught the scene with a glance.

IN MEDIAS RES

In medias res is a Latin phrase used by the poet Horace; it means “in the middle of things.” Poet Horace was describing the ideal epic poet.

IN STATU NASCENDI

In statu nascendi is a Latin phrase and means “in a state of being born”.

When a story begins in medias res (in the middle of things) and the character is given no backstory, we may say the character is presented to us in statu nascendi.

A good example of a picture book which begins in statu nascendi is Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day by Judith Viorst, although modern picture books tend to begin this way in general. Older style picture books often have a short build up which describes what a character does regularly (the iterative), then switches to the singulative when describing what happens in this particular story.

Integral Setting

(As opposed to backdrop setting): Describes a setting which is an essential part of the story. It may even be considered a ‘character’ in its own right. If the setting were anything else, the story would not be the same or would not work at all.

INTERROGATIVE TEXT

An interrogative text has the force of a question.

In an interrogative text, authority is questioned. Harry The Dirty Dog is an example. Carnivalesque texts are interrogative by their function.

Intraiconic text

Writing that appears as part of an illustration, such as book titles on spines of books, writing on a computer screen, an addressed envelope. Slows down our ‘reading’ of the visual text and adds to the text-image tension.

The illustration below is especially interesting because the intraiconic ‘text’ is also a picture.

Irony

A rhetorical figure based on a deviation from the dictionary meaning of words. Irony cannot be expressed by pictures alone, but can be achieved when the words in a picturebook don’t match up with the pictures, creating an ironic counterpoint. In order to work, all stories everywhere need a certain degree of irony.

Picturebooks are ironic in ways specific to picturebooks.

In their book How Picturebooks Work Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott came up with a taxonomy to describe how words and text work together to tell a story. When picture and text do not line up, they say there is ‘ironic distance’ between them. The difference between a picturebook (one word) and another kind of illustrated text: Picture and text must be working together in some way to create something new.

Here is the taxonomy they came up with:

- SYMMETRY: Words and pictures are on an equal footing.

- COMPLEMENTARY: Words and pictures each provide information.

- ENHANCEMENT: Words and pictures each enhance the meaning of the other.

- COUNTERPOINT: Words and pictures tell different stories.

- CONTRADICTION: Beyond different narratives, words and pictures tell the opposite of each other.

Nikolajeva and Scott are talking about the ironic distance between words and pictures in terms of narrative.

There’s another layer of ironic distance which comes from mood (for lack of a better term).

In a NYT review of some illustrated fairytales, Maria Tatar says the following:

Though [Lisbeth] Zwerger’s watercolors are sometimes disturbing, the decorative beauty of her work also functions as an antidote to the violent content of the tales. This dynamic is reversed in Hague’s “Read-to-Me Book of Fairy Tales”: Allison Grace MacDonald’s gentle prose mitigates the ferocity of some of Hague’s illustrations.

A beautiful picture can moderate violent images in a horrific story. Likewise, a sweet, innocent story can be spiced up by ferocious and daring illustrations.

Isochronic(al)

A story is isochronic if the timespan of the story and the time it takes to read the story (the discourse timespan) are the same. See also: Talking about story pacing.

JATAKA STORIES

Sometimes called birth stories, Jataka are accounts of the previous lives of the Buddha in vairous animal and human forms. They have been absorbed into the folklore of many countries. Jakata tales have many similarities to the Panchatantra and Aesop’s fables.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

Picture book examples:

Buddha Stories (1997) illustrated by Demi

The Brave Little Parrot (1998) illustrated by Susan Gaber

Foolish Rabbit’s Big Mistake (1985) illustrated by Ed Young

KINDERCULTURE

Shirley Steinberg and Joe Kincheloe came up with the concept of ‘kinderculture’: a new form of children’s culture which emerged in the late 20th century. This culture was driven by “changing economic realities coupled with children’s access to information about the adult world.” The 1980s marked the beginning of the boom in children’s consumer culture. Before then, marketers didn’t target children directly.

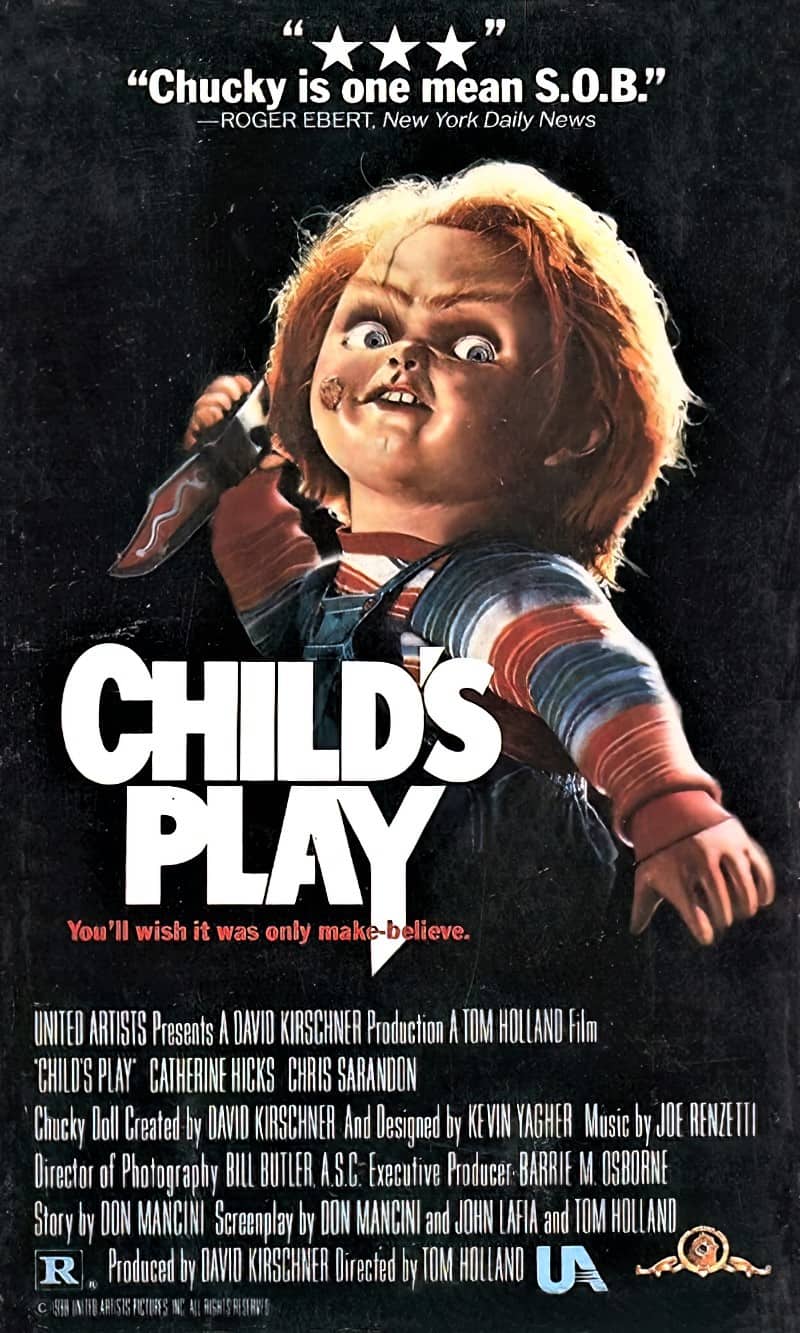

People were feeling pretty anxious about this change. The horror film Child’s Play (1988) feels like horror comedy now, but is all about those very real 1980s anxieties. A doll literally talks directly to a vulnerable child without the safe go-between of the adult.

The main concern for parents of the 2020s is that children have direct access to the entire Internet without the safe go-between of the adult.

LOW CHROMA

Chroma is another word for ‘saturation’ and describes the departure degree of a color from the neutral color of the same value.

Colors of low chroma are sometimes called “weak”.

Literacy

Most often, two distinct things:

- learning to read and write

- such things as drawing conclusions, making associations and connecting text to reality

There is another kind of literacy required for reading digital stories: technical literacy—knowing how to progress through a story. A higher level of literacy again involves creating meaning, understanding and at the same time being critical. There is no evidence that literacy, in and of itself, leads to the cognitive functioning of, for example, logical, analytical, and critical thinking that the ‘literacy myth’ prescribes.

LiteraRY

In literary fiction, style is paramount, the work is thematically integrated, character is rounded, originality at a premium. Contrast with genre fiction.

LUDIC READING

‘Ludic’ or ‘absorbed’ reading is a virtually trance-like state in which readers willingly become oblivious to the world around them. The term as used here comes from Hugh Crago and Victor Nell.

Magic realism

Some people think that ‘magic realism’ is an unnecessary term to describe a type of low fantasy, for people who don’t like using the word ‘fantasy’. Others believe we should be making more use of the word fabulism. A highly political term, magic realism generally describes a story which seems grounded in our real world but which contains fantastical elements.

MAN BITES DOG HUMOUR

‘Man Bites Dog’ describes inversion humour. I’ve also seen ‘hat on a dog’ describing the same category of joke, in which the audience laughs because the usual way of things is back to front.

MARK TWAIN WINK

Mark Twain is famous for a style of narration in which a narrator cracks jokes which tend to go over the heads of child readers and appeal to the adult co-reader. We also see E.B. White and A.A. Milne writing in this way. We might hypothetically see this in picturebooks, though contemporary writers usually mean something different when they’re talking about picturebooks and ‘winks’.

The wink commonly refers to the ending in which a careful observer notices there’s something more to the story. Commonly there’s a clue which tells the reader the story is about to repeat, or that magic is actually real.

MATERIAL BODILY PRINCIPLE

This is Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin’s term. Picture books about the human body and its concerns with food and drink (commonly in hyperbolic forms of gluttony and deprivation) are stories about the material bodily principle.

Gross-out middle grade texts are often concerned with excretion (usually displaced into opportunities for getting dirty). Sometimes we get gross-out picturebooks, too. The Disgusting Sandwich is one example.

In stories for older readers this turns into concerns with sexuality (often displaced into questions of undress).

Harry The Dirty Dog (1956) is a good example of a picture book concerned with the body and the unfortunate need for maintenance.

Below: “The History Of The Dirty Child” from Slovenly Peter, or, Cheerful stories and funny pictures for good little folks illustrated by Hoffman Heinrich

Metafiction

Fiction which draws attention to the fact that it is fictional, not attempting verisimilitude. In children’s literature, directly addressing the reader (or ‘breaking the fourth wall’) is a common metafictive technique.

METAPHORICAL GENDER

Beef vs. chicken’ is a classic example of what’s known as ‘metaphorical gender’, where the two items in a pair are judged to express a masculine/feminine contrast despite having no directly gendered meaning—other examples include ‘square vs. circle’ and ‘knife vs fork’

language: a feminist guide

- dog vs. cat

- blue thing vs. pink/purple thing

- cottage cheese

METATEXT

Meta, meaning all, refers to the coming together of text and image. All elements of a picturebook must be seen in relationship to each other. One element may be dominant on first appearance, though all contribute to meaning.

I’ve also heard metatext to mean a secondary text which talks about a main text. (The person writing or talking has to first define which is the main text, in the same way they have to define diegetic levels.)

Mimetic

Communicates by showing. Illustrations are inherently mimetic. Mimetic is the flipside of diegetic.

Mise en scène

Mise en scène is a ‘grand, undefined term’ which in film refers to the arrangement of space and the objects within it. The following things all contribute:

- sets

- props

- acting styles

- lighting

- camera angles

- and other elements

The concept may also be useful when describing picturebooks.

On the one hand, mise en scène describes the limits of human experience by indicating the external boundaries and contexts in which people live. On the other, it reflects the powers of the characters and groups that inhabit it by showing how people can have an impact on the space in which they live. While the first set of values can be established without characters, the second requires the interaction of characters and mise en scène.

From The Film Experience: An Introduction

Mise en scène as an external condition indicates surfaces, objects, and exteriors that define the material possibilities in a place or space. One mise en scène may be a magical space full of active objects; another may be a barren landscape with no borders.

- The interiors of trains and subways, with their long, narrow passageways and multiple windows and strange anonymous faces mean that a character’s movements are restricted as the world flies by outside (The Lady Vanishes, The American Friend).

- Deserts and jungles can be threatening to visitors (King Solomon’s Mines, The African Queen)

Mise en scène as a measure of character dramatizes how an individual or group establishes an identity through interaction with (or control of) the surrounding setting and sets. The mise-en-scène and the character mutually define each other, although the mise-en-scène may be unresponsive to the needs and desires of the characters.

- A forest can be a sympathetic and intimate place (Robin Hood) or it can be an environment fraught with psychological significance (“The Company Of Wolves“).

- A wide open space can expand the characters’ horizons (Brokeback Mountain).

Monoscenic Narrative

Monoscenic art represents a single scene with no repetition of characters and only one action taking place.

MULTIMODAL NARRATIVE

A digital story is defined as a ‘multimodal narrative’ text comprising pictures, music, speech, sound and script.

Mythopoeia

The creation of artificial myths; artificial mythology (see also: pourquoi story)

NAIVE ART STYLE

Naïve illustration is created by, or mimics, an untrained artist with a distinct style that is characterized by simplicity and bold colour choices.

See also Vanishing art.

Vanishing art style and naïve illustration are both forms of art, but they have some key differences.

Vanishing art style refers to art that is expected to disappear over time due to its ephemeral nature and its creation on non-permanent surfaces. It is typically created quickly and spontaneously, and the artist may choose to remain anonymous.

Naïve illustration, on the other hand, refers to art that is created by an artist who lacks formal training or education in art. This can result in a style that is characterized by simple forms, bold colours, and a lack of attention to technical details. Naïve illustrations can be created on a wide range of surfaces and materials, including paper, canvas, or even found objects.

Narratology

The theory and study of narrative structure.

Visual representation of setting is ‘nonnarrated’, and therefore nonmanipulative, allowing the reader considerable freedom of interpretation.

from How Picturebooks Work by Nikolajeva and Scott

Negative space

Most often white space, sometimes negative space comprises another colour such as black. In many ways, picturebooks are like film, but negative space is not an option in most kinds of films, where there has to be some kind of backdrop. Advantageous because lack of setting means a story may not date so much.

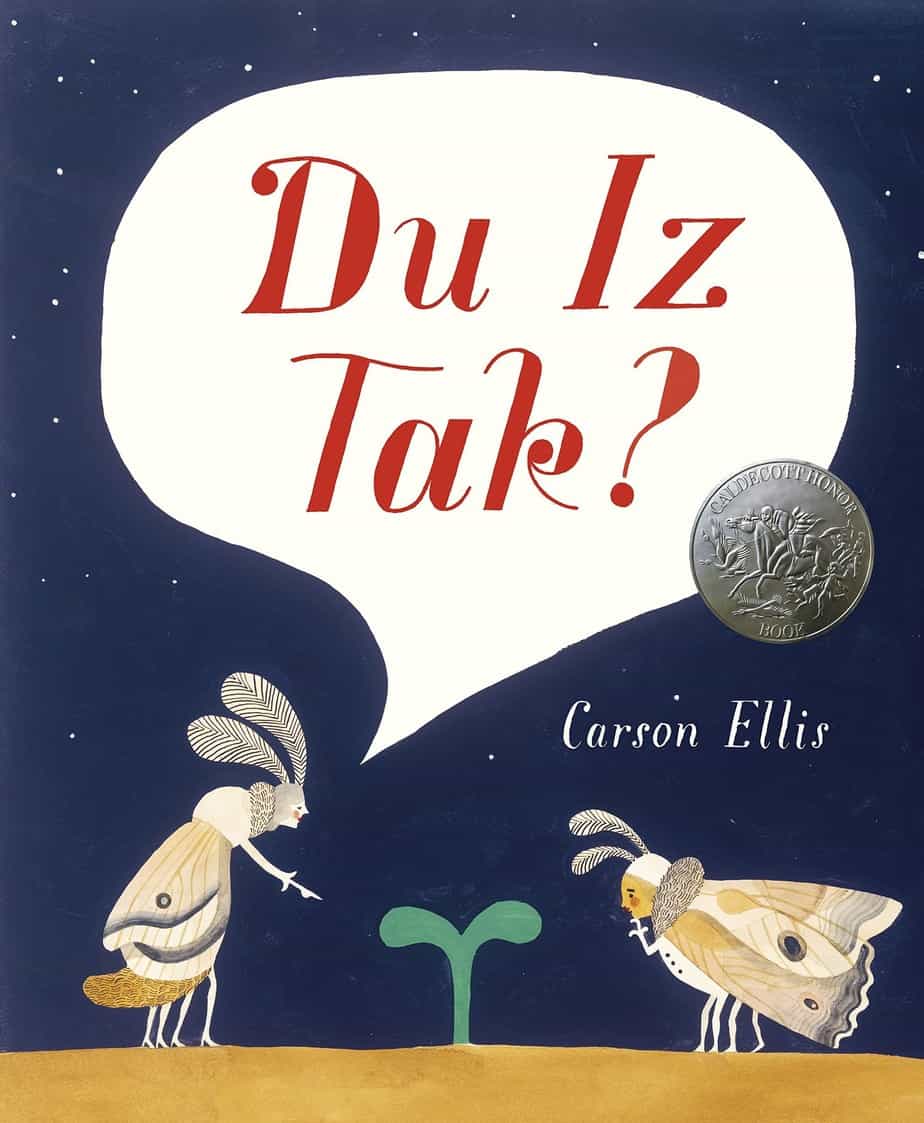

Nonce Words

Technically, nonce words are signifiers that lack the signified. In effect, these tend to be words used for the purposes of this story only. Also called ‘occasionalism’. Fictional coinages do not fill any lexical gap, nor do they enrich the lexicon. Thus, the ‘one off’ characteristic of fictional coinages is a predominant feature of such new words. In literature, the main motivation for new word formations is not to enrich the lexicon but to enrich the text itself. Since there is little chance for literary coinages to enter the language, they can be classified as nonce formations.

Note: The word ‘nonce’ is not related to the word ‘nonsense’. It means ‘for the once’.

That said, every now and then a nonce word from a very popular children’s book does enter the shared lexicon. Runcible probably comes from Edward Lear’s limerick The Owl and the Pussy-cat (1870).

The difference between a neologism and a nonce word: Neologisms are young words which have occured naturally in our shared lexicon. Nonce words are performed for a work of art, and, generally, remain meaningful only within that work of art.

The popularity of Dr. Seuss has given rise to what we now call ‘The Seussian idiom’. See ”If I Ran the Circus” and ”Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book”, which initiate young readers into the enjoyment of language. When learning to speak, children learn to master the phonetic patterns of their mother tongue(s) by babbling streams of plausible but nonexistent words. This explains the popularity of made-up language with early readers.

NONSENSE

Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that balances elements that make sense with some that do not, with the effect of subverting language conventions or logical reasoning. … The effect of nonsense is often caused by an excess of meaning, rather than a lack of it.

Gibberish, light verse, fantasy, and jokes and riddles are sometimes mistaken for literary nonsense, and the confusion is greater because nonsense can sometimes inhabit these (and many other) forms and genres.

Wikipedia (Literary Nonsense)

Anne Carroll Moore, superintendent of children’s work for the New York Public Library system, called Dr. Seuss the American counterpart to Edward Lear, the tentpole author of British nonsense. Lewis Carroll popularised nonsense literature further. But some (e.g. Leonard Marcus) say Dr Seuss is not really a nonsense writer. He uses nonsense as a device to hold the interest of the reader.

A picture book example of nonsense is Meal One by Ivor Cutler.

Laura E. Richards and New Zealand’s Margaret Mahy are rare female examples of nonsense writers. (Nonsense may be related to the Tall Tale tradition, which is also masculine.)

NOW BOOKS

We can divide picture books into two main categories depending on whether they have a complete story structure or not. If they do, we call them ‘storybooks’. If they don’t, we might call them ‘now books’. Now books instead focus on presenting a particular moment or theme in a child’s life. These books may have illustrations and minimal text, and are used to help children learn about and understand the world around them.

Now books include:

- Richard Scarry’s Look Books

- Everywhere Babies by Susan Meyer and Marla Frazee

- Charlie Parker Played Be-Bop by Chris Raschka

Now books may give the pleasure of immersion in narrative, but they frequently do something else besides. There is no character arc in these books.

NUNC STANS

Although it literally means ‘now standing’, a better translation is something more like ‘everlasting now’.

In Christianity and in philosophy this Latin phrase means eternal existence as an attribute of God. In literature is refers to a moment of stasis or stillness. The phrase can convey a sense of the present moment being frozen in time, and can be used by writers to create a sense of contemplation or reflection. It may also be used to describe a moment of great significance or importance that is frozen in time.

Some stories attempt to ‘overcome time’. Winnie the Pooh might be said to work with the everlasting now. The characters never age. Same could be said for The Simpsons.

Oral Tradition

Some children’s authors write in the style of oral tradition. Enid Blyton is a good example, as is folklore, making use of formulaic language, schematic and derivative characters, stories which change to suit the circumstances of time and audience and an open form. (Contrast with ‘literature’.) Oral traditions are no less valid than literary works. Stories making use of the above conventions might be described as ‘written folklore’. This type of story has a low status, partly because of its popularity.

Panoptic Narrative Art

Panoptic narrative art depicts multiple scenes and actions without the repetition of characters. Think of the word ‘panorama’. ‘All-seeing’ (pan + optic). Panoptic art encompasses multiple perspectives or points of view.

This can be achieved through various techniques, such as using multiple characters or viewpoints, or by using non-linear or interactive elements to convey a sense of a complete and holistic understanding of the story.

Parallelism

Parallelism refers to the use of similar or corresponding structures in language or writing. In literature, parallelism can refer to the use of repeated grammatical structures or similar phrase patterns to create a sense of balance and unity in a text.

Parallelism and symmetry are related concepts, but they have distinct meanings.

Symmetry refers to the balance and proportion in design or composition. Symmetry can be found in many forms of art, such as painting, sculpture, and architecture. It can be described as the balance and proportion of design elements, such as shapes, colours, and patterns, and can be achieved through the use of geometric shapes or repeating patterns.

So, parallelism is a literary device and symmetry is a visual one. Both parallelism and symmetry have to do with balance and repetition but in different ways.

An example of parallelism in literature is the repetition of similar grammatical structures or phrase patterns to create a sense of balance and unity in a text.

In Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” the first and second stanzas both start with the phrase “Two roads diverged in a wood,” creating a sense of parallelism that emphasizes the theme of choices and their consequences.

Another example is from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, when the character Gandalf says: “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” This phrase is repeated several times throughout the novel, serving as a reminder of the gravity of the characters’ quest and the importance of making wise choices.

At this point you may be wondering how parallelism is different from motif, another type of repetition you find in literature.

Parallelism refers to the use of similar or corresponding structures in language or writing e.g. repeated grammatical structures, similar phrase patterns. These structures are repeated to create a sense of balance and unity in a text.

But motifs are in the imagery family. A motif is any kind of meaningful repetition which unites a work at the level of metaphor. A motif helps audiences enter the thematic level of a work.

A motif can be literally anything: from a specific object or image, to a color, or even a sound or word.

Paralepsis (paralipsis)

In a word: omission. Also spelled paralipsis. The device of giving emphasis by professing to say little or nothing about a subject, as in not to mention their unpaid debts of several million. In picturebooks, too, a kind of paralipsis can happen when something mentioned in the text is left out of the picture, or vice versa. Negative space might be said to be the picturebook equivalent of paralipsis. For example, a page might be deliberately left blank because the character has disappeared for a time. An empty chair may draw attention to the fact that its usual occupant has died (See The Heart And The Bottle by Oliver Jeffers. Paralepsis can also be a secondary narrative in which time is independent of the primary story. For example, there’s a paralepsis in Where The Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, when Max travels ‘through night and day and in and out of weeks and almost over a year’. This kind of anachrony is common in picturebooks which describe an imaginary journey. For example, all the happenings of Narnia can’t possibly fit into the time the children would’ve spent at the country house.

Paratext

Gerard Genette’s word for the sum of the peritext and epitext. Peritext is within a book aside from the author’s words whereas the epitext includes author interviews and other marketing materials.

Readers may make of my work whatever they please…The problem with my telling people what I think it means is that my interpretation seems to have some extra authority and that sometimes shuts down debate: if the author himself has said it means X, then it can’t mean Y. Believing as I do in the democracy of reading, I don’t like the sort of totalitarian silence that descends when there is one authoritative reading of any text.

Philip Pullman

Participation

Academics are distinguishing between the several possible meanings of the concept participation:

- conventional participation, such as letters decoding or the passing of pages or screens

- active participation, a complex interpretive demand related to a postmodern configuration of meanings

- interactive participation, or physical cooperation with the work

Pedagogical Applications

Used to describe parts of a story which encourage some sort of learning, for example via puzzles, counting things, finding objects.

PERITEXT

All the physical features within a book aside from the author’s words. Front and back covers, dust jacket, endpapers, half-title and title pages, and dedication page all work together with the text and accompanying illustrations to produce a unified effect. These are known as a work’s peritext, a term first used by Gerard Genette in 1987.

An example of a picturebook in which the peritext starts the story is Rosie’s Walk. Virtually all of the story is on the title page of Rosie’s Walk, with one little exception. The fox exists only the pictures, never in the text, so immediately there is a tension between the text and the illustrations.

PICTUREBOOK APPS

Short for application software: Software designed to accomplish specific user tasks (in contrast to “system software”).

PICTUREBOOK EBOOKS

While e-books are single files that require specific software (e-reader software), apps (being software) run by themselves.

Point-of-View

In a picturebook, point-of-view might be conveyed via the text or via the perspective of the illustration.

The most common point of view in modern novels is ‘close third person’, which contemporary readers are used to. In children’s novels, introspective narrators are common. Picturebooks tend to be narrated (via the words), with the point of view expressed (via the illustrations) by facial expressions and body language, in particular. Pictures are very good at presenting an omniscient perspective via panoramic views of settings/various scenes of different characters doing different things.

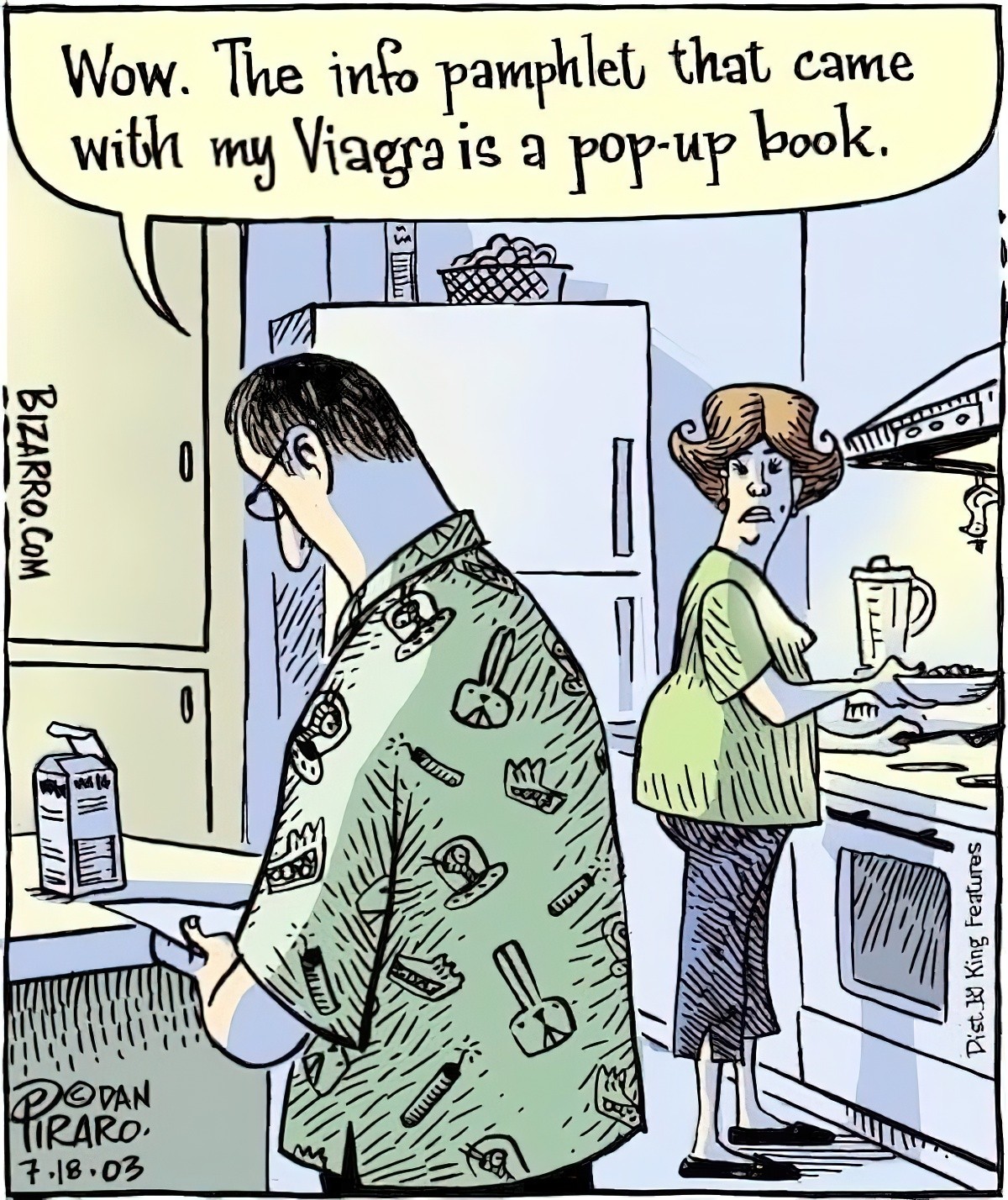

POP-UP BOOK

The term pop-up book is often applied to any book with three-dimensional pages, although it is properly the umbrella term for movable book, pop-ups, tunnel books, transformations, volvelles, flaps, pull-tabs, pop-outs, pull-downs, and more, each of which performs in a different manner. Also included, because they employ the same techniques, are three-dimensional greeting cards.

Wikipedia

POSTMODERN

In postmodern picturebooks: reality is presented as less certain than assumed, meaning is not inherent to the work, non-linear narratives are common, the voice is often sarcastic and self-mocking, it is frequently self-referential, metafictive and anti-authoritarian. The reader is required to complete the story themselves after thinking about it.

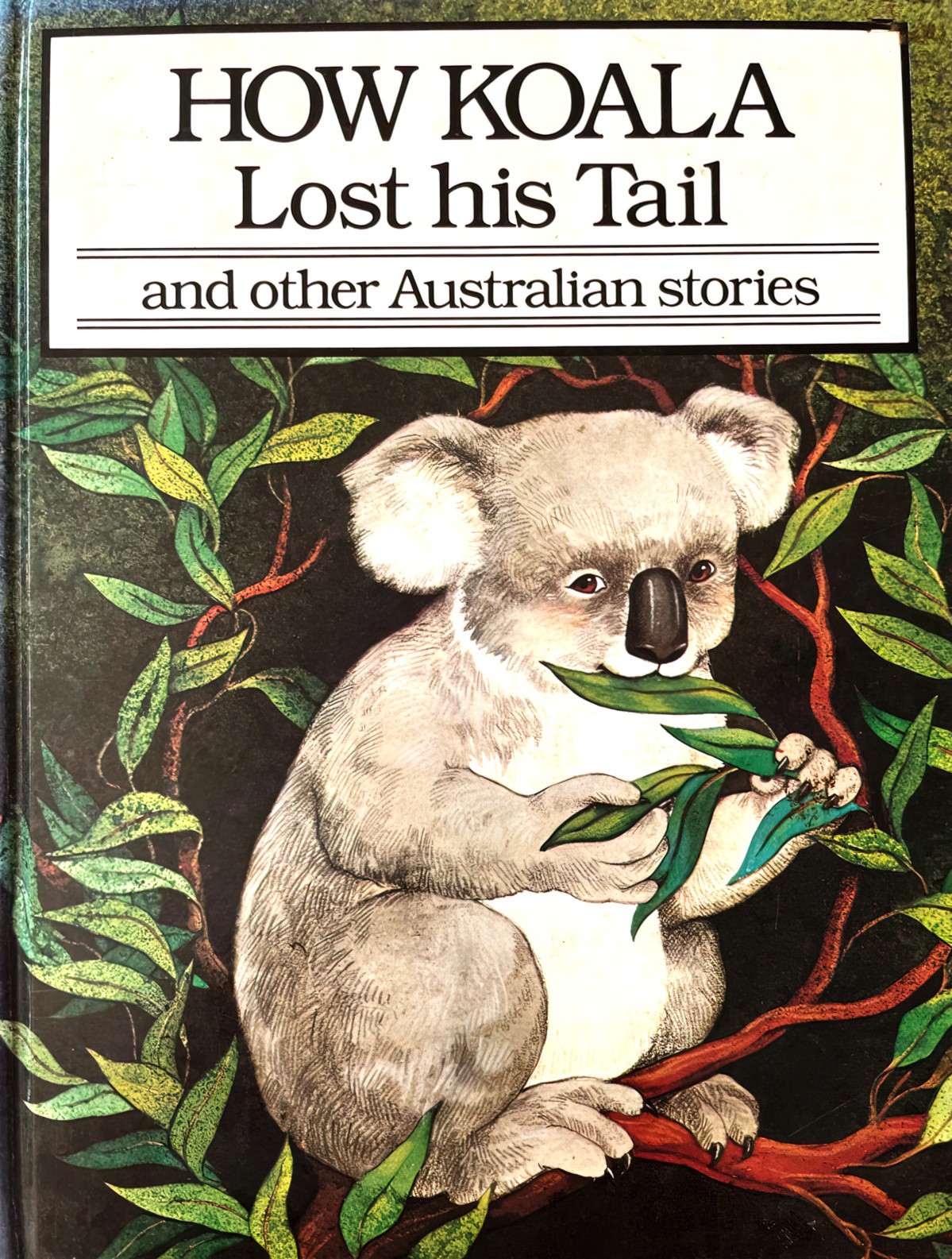

Pourquoi story

Also known as an origin story or an etiological tale, a pourquoi story is a fictional narrative that explains why something is the way it is, for example why a snake has no legs, or why a tiger has stripes. A classic example is Rudyard Kipling’s collection of Just So Stories. See also: mythopoeia.

Prolepsis

A flashforward/anticipation. The opposite of analepsis. A secondary narrative that is moved ahead of the time of the primary narrative.

Reading event

Describes the ‘lived experience of reading — the experience of sitting down to read a picturebook — from cover to cover — as opposed to ‘studying’ a picturebook, or examining some part of it.

Recto and Verso

the front (recto) and back (verso) of a leaf of paper in a book

REDUCTION

Reduction can make texts intended for both adults and children appear to have been written for children alone. For instance, the fairy tales of Hans Chritian Andersen have long been considered solely children’s stories in the English speaking world because of their translations into English…this was a reduction of multiple address.

from Comparative Children’s Literature by Emer O’Sullivan

Register

A variety of a language or a level of usage, as determined by degree of formality and choice of vocabulary, pronunciation, and syntax, according to the communicative purpose, social context, and social status of the user. In picturebooks the word ‘register’ describes a kind of atmosphere evoked by both words and pictures together e.g. grotesque, nostalgic, everyday registers.

REMEDIATION

Remediation is the act of remedying or correcting something that has been corrupted or that is deficient. But in the context of picture book media, the usage is difference.

Whereas books are ‘adapted’ for screen, books are ‘remediated’ as apps.

REPEATED READING

Picture books must stand up well to repeated reading. There are developmental reasons why children return to the same books time and again.

It may be that narrow input is much more efficient for second language acquisition. It may be much better if second language acquirers specialize early rather than late. This means reading several books by one author or about a single topic of interest.

from The Case for Narrow Reading by Stephen Krashen

What makes a picturebook re-readable?

Rhymed prose

A literary form and literary genre, written in unmetrical rhymes. One famous example of rhymed prose is Lewis Carroll’s “The Jabberwocky”.

See also:

- “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”

- “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe

ROUNDS

Stories which begin over and over again and repeat.

There’s a long history of rounds in folk tale. See the ROUNDS entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

SCOPOPHILIA

A love of looking. Film theorist Laura Mulvey uses it. Comes from Freud.

Although the word is sometimes associated with voyeurism (the act of secretly watching others without their knowledge or consent), it is also used in the context of visual arts, film and media studies, to describe the pleasures of looking at the spectacle, the visual pleasure of watching movies, TV shows, picture books and other media forms.

So, the word scopophilia is often associated with the pleasure of looking at something as a form of entertainment, as well as the pleasure of looking at something as a form of power or control.

Simultaneous Succession

Widely used in medieval art (in ‘hagiographies’, depicting the life of a saint), this term implies a sequence of events. Think of those cave paintings showing a stick figure with a spear, hunting down an animal. The moments are disjunctive in time but imply a sequence. For example, a series of pictures in a picturebook might show a child getting ready for bed: pulling off her jumper, taking off her shoes, brushing her teeth, retrieving teddy bear, getting under the covers. This technique of showing the passing of time works better for slightly older children, because younger children may interpret a series of pictures of this girl getting ready for bed as five different girls. (However, adult co-reading is assumed.) The books of Sven Nordqvist make much use of simultaneous succession. This is most often a type of continuous narrative art.

Simultaneous Narrative Art

Not to be confused with ‘simultaneous succession’. In this kind of illustration, everything in a picture appears to be happening at once. This kind of illustration has very little visually discernible organisation unless the viewer is acquainted with its purpose. There’s an emphasis on repeatable patterns.

Simulative Participation

The user is given the illusion of doing something that actively moves the story along but in fact the user is not free but must adhere to, say, the app programming, if we’re talking about book apps.

Single Address

When an author intends only to write a picturebook for children, even if the picturebook ends up being enjoyed by adults anyway. (See double address. Not to be confused with ‘dual audience’) It may be useful instead to think of multiple addresses rather than an either/or.

Screentone

When lots of tiny dots are used to fill a shape. Is still used today in manga, so if screentone is used in a modern picturebook, it’s likely to evoke a retro or comicbook feeling.

Solipsism

The philosophical idea that only one’s own mind is sure to exist.

Speed, Order and Frequency

These categories are helpful when applied to hypertextual structures and further distinguish between empirical and computed behaviour or strategies.

For example, the computed minimum or maximum speed for progressing from one page to the other might substantially differ from the empirical speed of a specific user at one specific running of the app.

Synoptic Narrative

A synoptic narrative depicts a single scene in which a character or characters are portrayed multiple times within a frame to convey that multiple actions are taking place. Synoptic is the adjective of synopsis.

Surrealism

A movement in art and literature that sought to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind, for example by the irrational juxtaposition of images.

Syllepsis

A poetic device, a type of zeugma. In picturebooks, this occurs when you see two or more parallel visual stories, either supported or unsupported by words. A fairly common example in picture books is when the pictures depict the lives of small creatures doing their own thing but who remain unmentioned in the main text. The plural of syllepsis is syllepses. See also: parallelism.

Symmetry

Maria Nikolajeva and Carole Scott have created a sophisticated taxonomy of picturebook interactions (between words and pictures) and came up with a sliding scale. ‘Symmetry’ is at one end, in which the pictures pretty much repeat what the words have already explained. At the other end is ‘contradiction’, in which the pictures say something completely different from the words, often creating irony or humour. The problem with having ‘symmetry’ at the ‘extreme’ end is that pictures cannot help but say more than the words, since ‘a picture tells a thousand words’ (or thereabouts). So there will never exist a perfectly symmetrical picturebook.

Teaching stories

A term used by writer Idries Shah to describe narratives that have been deliberately created as vehicles for the transmission of wisdom. Teaching stories include folktales, fables and didactic fairytales.

TEXTUAL NARRATOR

In stories without pictures we talk simply of narrators, but in picture books with a meaningful gap between the story told by the words and the story told by the illustrations (e.g. Rosie’s Walk) we might specify the narration as told by the words, in which case I have heard ‘textual narrator’.

THEME

The concept of theme means different things in different settings. In high school literature class we are told that ‘theme’ is a word — a sort of abstract noun like ‘love’ or ‘independence’. This is okay — this gets most students passing year 11 English, but if you go on to study literature, or if you’re a writer, the single word example of theme isn’t enough.

THEME AS USED IN EVERYDAY ENGLISH: “Well, the theme of today’s meeting was definitely muffins.” In everyday usage, ‘theme’ can refer to any collection of ideas which are somehow connected.

DEFINITION FOR WRITERS: A theme is a sentence, not a single word.

Theme is a coherent sentence that expresses a story’s irreducible meaning.

WAR is not a theme. War is a setting.

LOVE is not a theme. Love is a genre (Romance, love story)

TEEN DRUG ABUSE is not a theme. Teen drug abuse is subject matter.

That said, when people talk about theme in relation to picture books they are often talking about the tags given to picture books by library cataloguers: family, friendship, loneliness etc.

TITLE

Titles (and headings) are a text-type in their own right. They serve a variety of functions and are of special interest to translators. Translated titles must fulfil the same functions in different markets. (This is why authors don’t often get a say in titles — it’s complicated!)

- DISTINCTIVE: A book’s title distinguishes it from other books. In some cultures (e.g. in Germany) there’s a law to protect book titles against unfair competition. Book titles must be unique.

- METATEXTUAL: Indicates information such as the genre of the book e.g. a funny, English language picture book

- PHATIC: Since titles are on the front covers, or appears on publisher’s lists and book recommendation sites, the title has a phatic function via first contact with the person looking at it. Length and memorability (mnemonic quality) is important here. If a title is too long and unmemorable the potential consumer won’t remember it, and the phatic function remains unfulfilled. (The word ‘phatic’ describes language used for general purposes of social interaction, rather than to convey information or ask questions.)

- REFERENTIAL: Offers information about the most important characteristics of the text regarding content/style. Information in a title must be comprehensible and acceptable for the recipients otherwise a title’s referential function remains unfulfilled. The title might say something about theme e.g. Pride and Prejudice. It might give us a clue about register Howe: The Day the Teacher Went Bananas. It might signal intertextuality e.g. William Faulkner: The Sound and the Fury.

- EXPRESSIVE: Gives the author’s opinion on the text or any of its aspects. Basically, this means titles convey opinions. Titles have positive, negative and neutral connotations, make use of evaluating adjectives and adverbs and so on. The evaluation might apply to something in the book e.g. The Prettiest Love Letter In The World or it might refer to the readers themselves e.g. Hillaire Beloc: Bad Child’s Pop-Up Book of Beasts. This function is heavily culture specific.

- APPELLATIVE: Evokes the attention and interest of readers, including those with no previous interest in this kind of book, because the publishing team and author desire this book to be purchased and read. Basically, titles are meant to appeal. There’s a subfunction as well: to persuade. To guide readers’ interpretation.

For more on this see Text Functions In Translation Titles and Headings as a Case in Point.

TRIM SIZE

A publishing industry term for the size of a printed book. Below, Leonard Marcus explains how trim size is important (in a conversation about ebooks and their limitations).

Barbara Basbanes Richter: You don’t sound like you are against the use of technology, rather in favour of its judicious employment.

Leonard Marcus: I’m not against technology, but it’s no substitute for a parent. And in certain respects, paper books function more effectively than e-books do. I think that these are two art forms that are going to both develop and each will put pressure on the other to do better at what it can do best. A Kindle, for example, can’t change its format. Every picture book has to be exactly the same size to fit in the screen, and that is a real problem for creator of picture books, whereas the trim size and other physical aspects of the book have always been considered expressive elements. But that’s not to say that some brilliant person couldn’t take an e-book – which is really a form of animation – and do something on an aesthetic level that someone working in a picture book format could only dream of doing.

from Book Chat Part One with Leonard Marcus at Literary Kids

TRIPLE PERSPECTIVE

Triple perspective describes works featuring figures seen from different viewpoints. They appear in one pictorial plane, resulting in distortion.

The foreground boy below is a non-picture book example of a figure depicted in triple perspective:

TOY BOOK

Toy books were illustrated children’s books that became popular in England’s Victorian era. The earliest toy books were typically paperbound, with six illustrated pages and sold for sixpence; larger and more elaborate editions became popular later in the century. In the mid-19th century picture books began to be made for children, with illustrations dominating the text rather than supplementing the text.

Wikipedia

User-Device Response Techniques

Describes the sort of interaction that happens between computer and user in games, but which is rarely seen in book apps. Book apps cannot offer the same narrative freedom of choice as role-play gaming where the user directs an avatar more or less freely through a virtual world.

- character editing

- various forms of multi-user experience which could be fruitfully applied to concepts of multiple fabula or alternative story apps to create alternative texts in interaction with other users.

- the introduction of blanks, either literally in the interface as free space where the user can fill in words, drawings, or photos of their own choice or by using the possibilities of the device that allows users to make videos, take photos, or record their own words all of which can then be integrated into the app as forming part of the narrative.

Vanishing Art Style

Some features of vanishing art styles include:

- Temporality: The art is not meant to last forever, and it is expected to disappear over time.

- Ephemerality: The art is created to be fleeting, and its existence is often brief.

- Environmentally sensitive: The art is affected by the environment in which it is created, such as weather, pollution, or human intervention.

- Unconventional mediums: The art is often created using unconventional materials or surfaces, such as walls, sidewalks, or natural rock surfaces.

- Spontaneity: The art is often created quickly, spontaneously and without prior planning.

- Public-oriented: The art is often created in public spaces and is intended for the general public to view.

- Anonymity: The artist often chooses to remain anonymous or unknown.

- Non-commercial: The art is often created for artistic expression rather than commercial gain.

- Design is often created with large colour areas, enhanced in specific places with details only to suggest important features or clues.

An example of a vanishing art style is cave paintings. These paintings, which were created by prehistoric humans, are found in caves around the world and depict images of animals, people, and other subjects. Due to their location in caves and the natural deterioration of the rock surfaces on which they were painted, many of these paintings have been lost over time and are now difficult to view or no longer exist. Hence: ‘vanishing’.

A modern example of a vanishing art style would be street art. Street art is created on buildings, sidewalks, bridges, and other public spaces using spray paint, markers, or other forms of graffiti. Because street art is created on surfaces that are not specifically designed for art display, it is often temporary and can be erased or painted over by property owners or city officials. Additionally, street art can also be affected by weather, pollution, and other environmental factors, which can cause it to fade or disappear over time.

A doodle on the back of a napkin is ‘vanishing style’.

Likewise, artwork done by kindergarten children is a type of ‘vanishing’ style. It’s not commercial, done spontaneously, can use all sorts of non-permanent media and so on.

Picture books which mimic (and encourage) childlike artwork are obviously not meant to be ephemeral, but can recall a vanishing, child-like style.

Verbal, Visual, and Sonic signs

The analysis of book apps calls for a broad use of the term “text.” The text of an app as I understand it comprises its totality of verbal, visual, sonic, and interactive elements, or the “surface” of the app as distinguished from the underlying structure of the source code.

Vignette

A small illustration or portrait photograph that fades into its background without a definite border. In picturebooks vignettes are often used to show the passing of time e.g. a child getting ready for bed might be depicted by the same child brushing her teeth, pulling on a nightgown then getting into the bed.

Visual motifs

Decorative designs and patterns used in visual artwork, such as rabbits (to indicate various things in different cultures, such as rebirth or fertility); sunbursts, curlicues etc.

Vita activa and Vita passiva

Those who are active versus those who passively consume.

The words come from philosophy, specifically from the German-Jewish philosopher and political theorist Hannah Arendt in her 1958 book “The Human Condition”.

When applied to literacy, vita activa emphasizes critical thinking and the ability to analyze and interpret texts. Vita passiva emphasizes the acquisition of information rather than the ability to think critically about it.

World literature

Is sometimes used to refer to the sum total of the world’s national literatures, but usually it refers to the circulation of works into the wider world beyond their country of origin.

Sometimes the German word ‘weltliteratur’ is used even in English to mean the same thing.

SEE ALSO

This list of art terms relates specifically to Vermeer, but includes many words that are useful when describing artwork in picture books.

Header painting: Carlton Alfred Smith – The Young Readers 1893