Trends in Finnish children’s literature mirror trends in the English speaking world, but Finland is possibly more keen to keep its unique culture alive via children’s books.

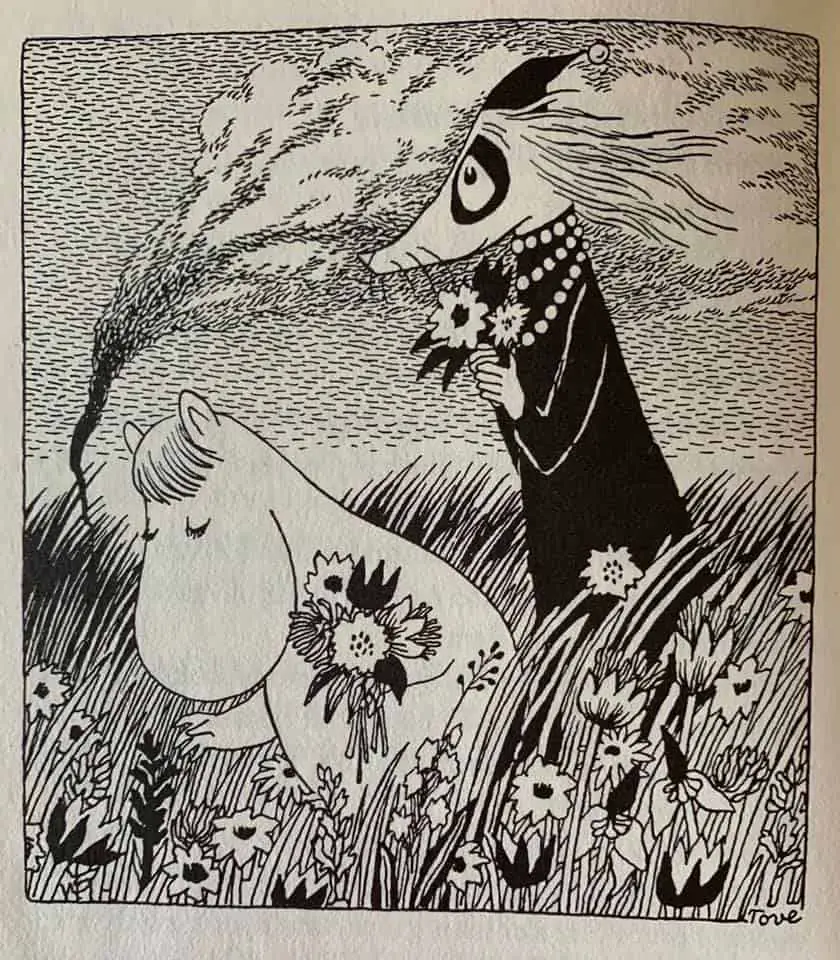

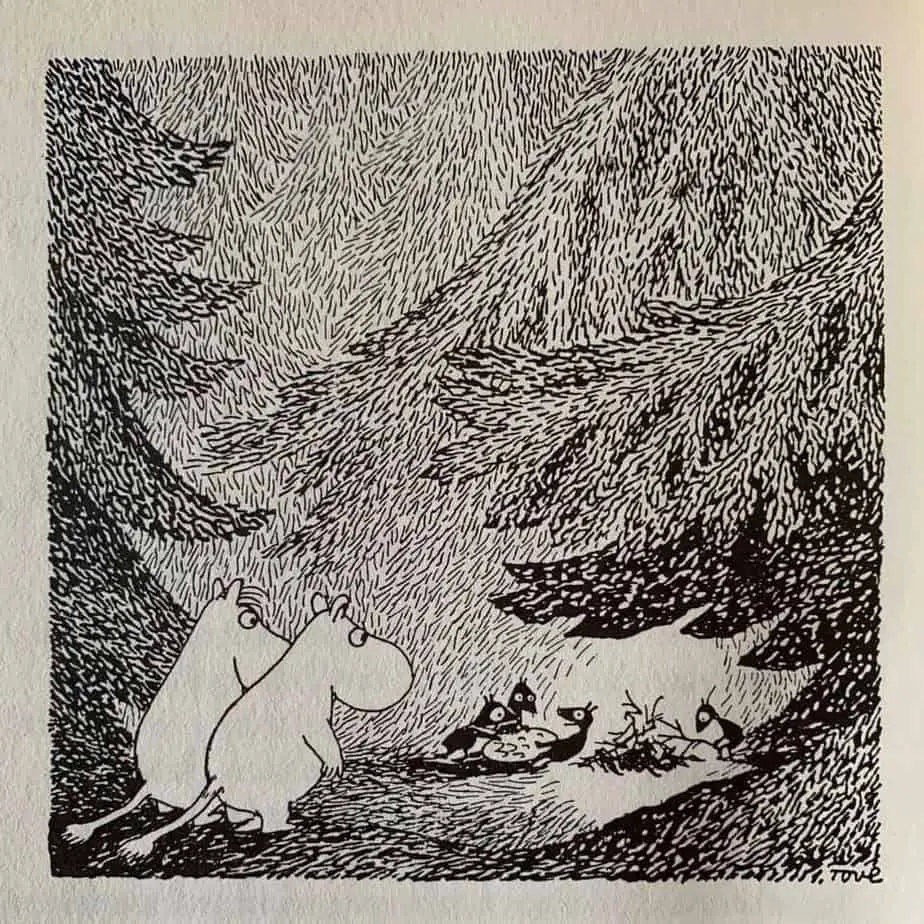

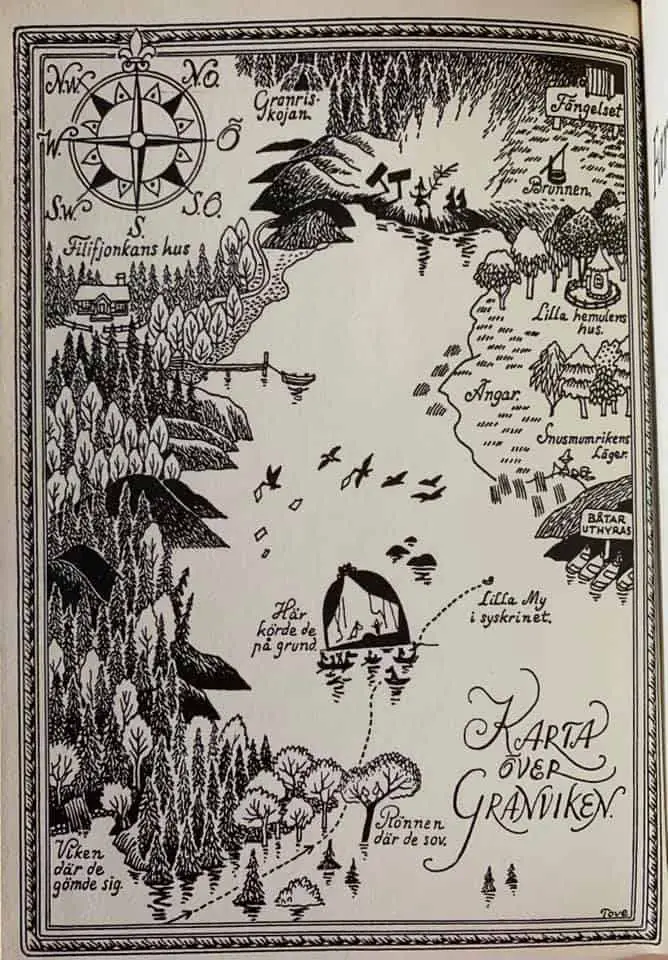

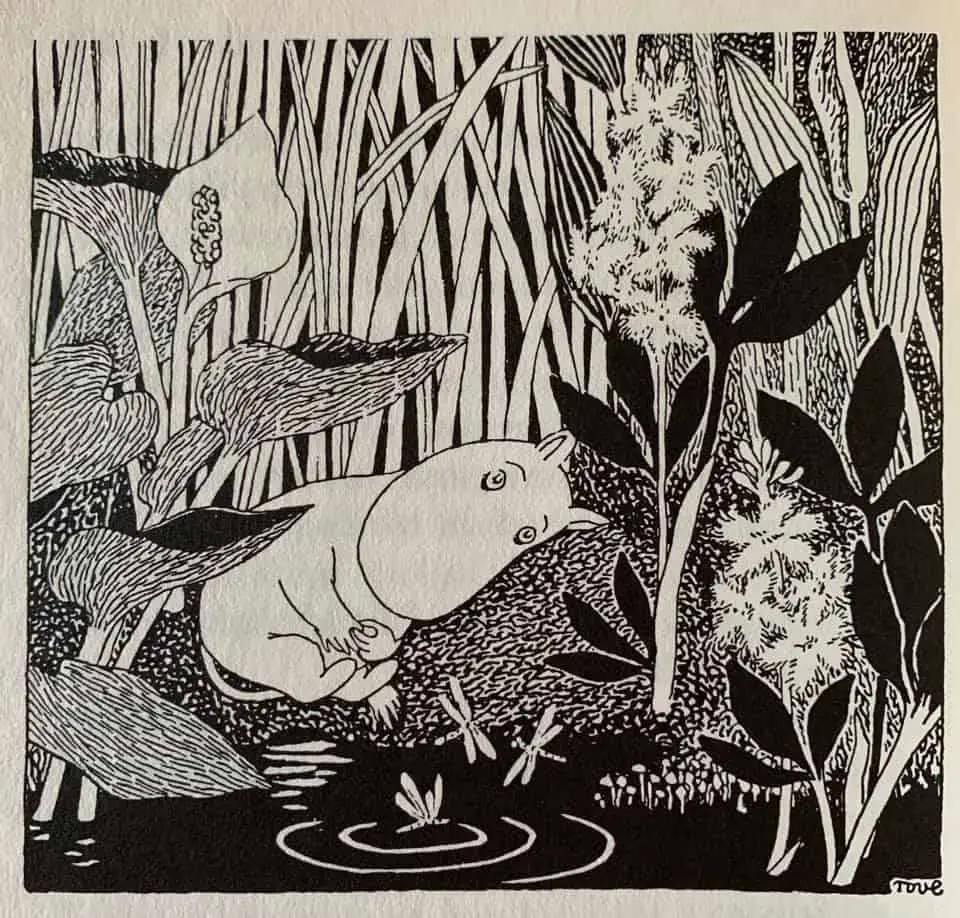

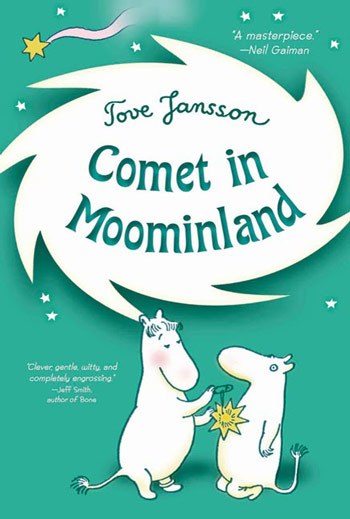

The Moomin stories are some of the weirdest and most inventive children’s books out there, and much beloved, especially in the Moomin family’s native Finland, where there is an entire theme park called Moomin World. Something rational tells us that we might want to work on getting the entire existing oeuvre readily available in the states before we start clamoring for more, but we feel like clamoring nonetheless.

Flavorwire

See also: It is a religion. How the world went mad for Moomins from The Guardian

Though best known outside her home country of Finland for the series of children’s books she wrote featuring the Moomins, Tove Jansson was also a wonderful writer of adult fiction. Featuring an old woman and her six-year-old granddaughter, The Summer Book retains the warmth and quirkiness of her children’s stories, but adds a layer of Nordic melancholy to the mix. There is no plot to speak of – Sophia and her grandmother simply share a summer on an island, talking, eating, laughing and exploring – yet this remains a charming and beautiful book, with prose that sparkles from beginning to end.

Best Loved Children’s Books In Finland

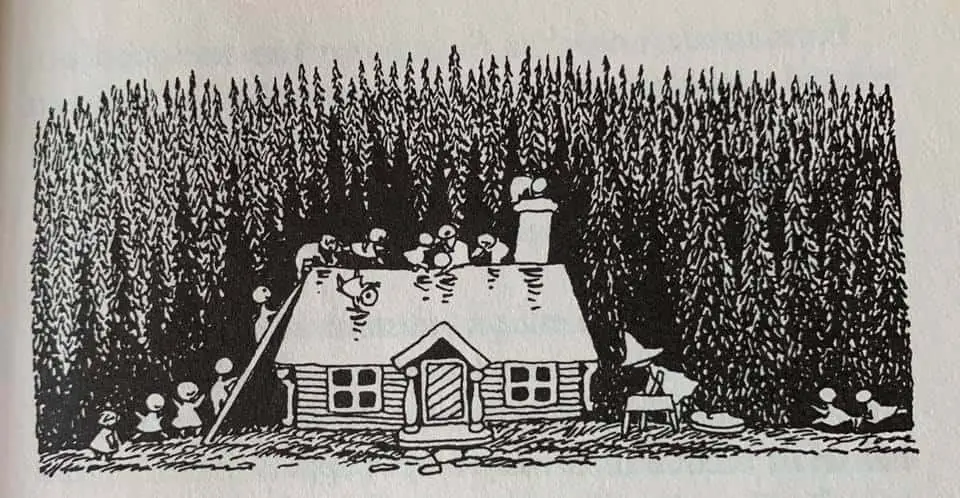

- books by Tove Jansson (who writes in Swedish). Tove was Finnish-Swedish, part of the Swedish speaking minority of Finland. She wrote her books in Swedish. The first ones were translated into Finnish after the English translations Many Swedes identify with settings and character as much as Finns do, though in some of her books her Finnish heritage is clear. Take Farlig midsommar (1954). This book shows that Tove was a Finn because the traditions of midsummer differ greatly between Nordic countries. In this book Tove depicts a Finnish midsummer rather than a Swedish one.

- Lena Krohn, the Minerva books

- Winners of the Finlandia Prize

- and also the Finlandia Junior award

- The popular Heinähattu ja Vilttitossu (‘Hayhat and Fluffshoe’, illustrated by Markus Majaluoma, Tammi) series of children’s novels by the sisters Sinikka and Tiina Nopola has now been relaunched for picture-book readers.

- Timo Parvela’s novel Ella ja Äf Yksi (‘Ella and F One’, Tammi), part of his Ella series set in a primary school, reached the silver screen last year in a film version directed by Taneli Mustonen.

- Dystopia, fantasy that reaches out into the future, is clearly on the way to becoming a new and trendy subgenre of domestic fantasy. The best examples include Annika Luther’s De hemlösas stad (‘The city of the homeless’, Söderströms), as well as Routasisarukset (‘The frost children’,WSOY), the splendid opening volume of Anne Leinonen and Eija Lappalainen’s fantasy trilogy…The realistic novel for young adults is clearly going through a critical stage.

- The number of self-contained (non-serial) novels for young people is decreasing. (From ‘Once Upon A Time’.)

- The classic novel by Aleksis Kivi. Joulupukki (1981), published in English as Santa Claus, is arguably the world’s best-known Finnish children’s book.

- Kirsi Kunnas (born 1924) is the queen of Finnish children’s poetry.

General Notes On Children’s Literature In Finland

- Finnish picture books for children have long been reliable export goods around the world…Now young adult literature has also blazed a trail on to the international market. (Books From Finland)

- There’s not much in the way of ‘anarchy’. (The first children’s book by Alexandra Salmela, who has previously published a novel for adults, brings some sorely needed anarchy to Finnish storybooks. – Alexandra Salmela: Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia [Giraffe mummy and other silly adults]

- Most Finnish board books have been following the contemporary trend for strong colour palettes with pared-down character designs. – from a review of Toivon talvi [Toivo’s winter] .

- The buyers of Christmas presents favour books written by Finnish authors.

- All new mothers in Finland receive a ‘maternity package’ from the state containing items for the baby (including bedding, clothing and various childcare products) intended to give each baby a good start in life. This tradition, which started in 1938, is believed to be the only such programme in the world. Each package also contains the baby’s first book, traditionally a sturdy board book by a Finnish author. – from Future, fantasy and everyday life: books for young readers

- Novels for beginning readers often carry an indication of the publisher’s recommended age range on the front cover. This has led to confusion among young readers as well as library staff who recommend books to readers. The first decade of the 21st century was a time of upheaval in Finnish reading culture, with diagnoses of various reading disorders, more entertainment options competing for children’s attention and the increase in the number of children from immigrant backgrounds all putting new demands on children’s literature. (from same source as above)

- Sci-fi/fantasy writing now appears to be taking over from realism in Finnish young adult literature. A number of authors who previously favoured realism (Salla Simukka, Laura Lähteenmäki, Anne Leinonen & Eija Lappalainen) have now turned their attention to dystopias, though the themes of independence and growth are still present in their new works. Supernatural romances with vampires and trolls are also making their presence felt in Finnish literature. (same)

- There is a tradition in Finnish children’s literature of giving an idyllic portrayal of the natural world. From a review of Mila Teräs & Karoliina Pertamo: Elli ja tuttisuu [Elli and the dummy]. Today, Finnish children’s relationship with nature is limited to the surroundings of the summer cabin.

- Modern picture books are influenced by traditional Finnish folktales such as the Kalevala, a Finnish folk epic. (See here for an online collection.) The Kalevala and other mythological subjects appear in Louhi, the adventure-packed final book in Timo Parvela’s Sammon vartijat (‘Guardians of the Sampo’) trilogy, in Reeta Aarnio’s children’s fantasy Veden vanki (‘The prisoner of the water’), and in Sari Peltoniemi’s Hämärän rengissä (‘The servant of darkness’), which is an imaginative combination of alternative history and fantasy. (reference here)

- The supply of titles for children and young adults is greater than ever, but the attention the Finnish print media pays to them continues to diminish.

- Literature aimed at older teenagers is coming close to matching the diversity of adult literature.

- Families in stories are increasingly diverse. Of the Finlandia Junior Prize, the chief judge said in 2010: ‘‘It caught my attention that in none of the six shortlisted children’s books are there any so-called nuclear families, at least not for long. The main characters constantly live and grow without something – the lack of parents or the attention of an adult is a serious matter to a child. However, in these books there is always someone who cares, not perhaps a stereotypical mom or dad, but an adult nevertheless.’

- The retro fad, with its interest in the lifestyles of previous eras like the 1960s and 70s can be seen not just in fashion and interior design, but also in children’s book illustrations, the delicate tones of the 70s can be seen both in the visuals and in the earnest didacticism reminiscent of 70s children’s books.