“Coming Soon” is a short story by American novelist and short story writer Steven Millhauser, first published at The New Yorker in 2013. (About 3,900 words.) Chang-rae Lee discussed this story with Deborah Treisman at the New Yorker Fiction podcast. The following are my thoughts after reading the story and listening to their discussion.

“You go to sleep one day, wake up and everything’s changed!” This is the sort of hyperbolic statement you might hear from someone describing the pace of change and their inability to keep up with it. Millhauser has taken a sentiment like this and turned it into something literal.

I believe this story has much in common with cosmic horror, and could be described as a contemporary version of that subgenre. Cosmic horror of the Edwardian era has limited appeal to modern audiences, but the big cosmic question remains: Do humans see reality as it really is? Like stories such as The Turn of the Screw, once you start reading this story, you realise that nothing in it is really clear. The less clear a situation, the more readers project our own personal nightmares onto it.

OTHER REASONS WHY THIS STORY IS INTERESTING

- I would like the term ‘spatial horror‘ to catch on, and I believe “Coming Soon” is an excellent example of spatial horror in use.

- Like John Cheever’s “The Swimmer“, “Coming Soon” is this weird realism/magical blend where the reader is not quite sure what’s real and what’s imagined. It’s a very dream-like experience, so oftentimes writers achieve this with an actual dream sequence, but if you don’t find hypodiegetic dream narratives interesting, this is an alternative way of depicting a character’s off-kilter psychology. Millhauser is known for creating stories which exist ‘on the level of the fantastic’. Although the town in this story becomes more and more defamiliarised, the strangeness of this parallel town is evident from the beginning.

- “Coming Soon” is mostly a description of setting. I mean, the description of the town comprises the bulk of words on the page. Sometimes commentators say a setting is a character in its own right. This story is the stand-out example of ‘Setting As Character‘. Chang-rae Lee uses the word “creatureliness” when describing this town. “A bike helmet lay sideways on a front lawn, like a gaping mouth.” As Chang-rae Lee also points out, this story ‘only works because the town becomes something else’. If you’re observant and good at writing beautiful sentences it’s easy enough to create a decent description of a setting. It’s something else again to turn that description of setting into a complete narrative and to have it say something about the nature of humankind, as Millhauser achieves here.

- “Coming Soon” is an example of a single character story within a single setting.

- The pacing is of interest because Millhauser makes use of every speed, including summary, scene, dilation, pause and — most interestingly, the gap, in which the main character wakes up and we wonder what just happened. Chang-rae Lee describes this pacing as a ‘quiet acceleration’, also seen in the work of Raymond Carver.

Readers will bring to this piece our own identities as rural, suburban or city dwellers. Until recently I lived at the end of a dark-night cul-de-sac in a semi-rural Australian suburb, but now live on a corner section on a suburban street with noisy thru-traffic and intrusive street-lighting. We haven’t moved. A new suburb popped up around us. I’m sure for the people waiting on their houses to be built the construction process felt like eons, but for me, the suburb seemed to pop up in an instant. Then, when my hometown was decimated due to a massive earthquake while I was away, the reconstruction process meant I no longer recognised central Christchurch when I returned. Suburbs once busy were now quiet; suburbs once quiet were busy.

Things change quickly when we’re not there, or even when we are there, and not paying them attention.

THE WISH-FULFILMENT FANTASY OF CONSTRUCTION

“Coming Soon” is an example of a story whose ‘making’ emulates its central motif. Millhauser is “constructing” for the reader a new way of looking at the familiar.

My own suburban experience and Millhauser’s story both remind me of a computer game called Cities: Skylines. Basically, the aim is to build a functional city without traffic congestion, sewerage problems and whatnot.

What explains the popularity of Cities: Skylines? Without adding all the cheat mods, it felt to me like I was working for council. The devs say, “It’s about bringing as much reality as possible, but making it real fun than it actually is [to manage a city] in real life.” Relating the popularity of Cities: Skylines to what I’ve learned about literature and genre, I believe these city-building games appeal to the specific wish-fulfilment fantasy of Empire Building. This widely-shared fantasy also explains the huge popularity of Western stories which dominated American men’s fiction in the first half of the 20th century. (It all changed after WW2, after which point Westerns were still called Westerns but were actually anti-Westerns, critiquing the fantasy of expansionism rather than glorifying it.)

“Coming Soon” isn’t exactly a Western story, but there are similarities. Like Ma and Pa of Little House on the Prairie, the main character of this story leaves the safety of community and, against advice of his tribe, insists on moving out to where he expects to find more opportunity and ‘pleasure’ of some kind. And once he’s there, he’s going to find pleasure, dammit.

Like Laura Ingalls-Wilder, who can write an entire chapter about the construction of a door, Levinson of Millhauser’s short story derives pleasure from the building of things. He is the sort of boyish man who enjoys watching big machines at work. He’s almost the construction equivalent of a train spotter.

Levinson also has what Lee and Treisman recognise as ‘small-town American pride’.

It’s rare to admit the specific pleasure derived from watching the construction cycle, as humans cannot keep building and rebuilding without also destroying our planet. In a rare acknowledgement of pleasure, a former colleague admitted to the quirky enjoyment involved in finishing off one box of tissues and opening a new one. This person was the super-organised type, and always had an extra packet of anything on hand. Simply buying that new box and seeing it there, waiting for use, was probably part of this small pleasure.

Short stories like “Coming Soon”, about a specific person in a specific milieu can encourage readers to examine our own psychologies. Do I, too, derive some pleasure from finishing and beginning new packets of consumables, even as I realise I’m contributing to landfill, or to the recycling load? If so, what is it specifically giving me the dopamine hit? Is it the feeling of ‘purity’ we get from starting something new? Is it the very minor promise of a fresh beginning? Is it the small punctuation in daily routine which makes us feel we’ve accomplished something, however minor?

SETTING OF COMING SOON

The pleasure of construction can co-exist with nightmares about climate change and environmental destruction. We can love a new kitchen and not give a thought to how the old one decompose for decades in landfill. This might be the tentpole cognitive dissonance of our age.

This morning on Facebook, someone shared a concerning article about new Sydney housing developments built in areas too hot for future habitation. One of the comments reminded me of Millhauser’s story, and confirmed that this American story could just as easily be an Australian one:

I too live in a leafy suburb in a popular school zone. Old houses get demolished and replaced with boundary to boundary dig out for cinema room and 6 car garage. Tall trees always go or to die, garden replaced with 1 deemed necessary canopy tree, usually a magnifolia grandiflora and rest is box hedge and standard roses.

Sydney’s New Suburbs Are Too Hot for People to Live In: Climate change is making things worse as Australia’s biggest city expands.

I mess with reality in the name of reality. Another way of putting it is that I don’t mess with reality. I mess with the assumption that reality is perfectly captured by middle-of-the-road realist fiction. I’d argue that the conventions of the realist story don’t begin to do justice to the blazing thing that deserves the name of reality.

Steven Milhauser, in response to the question, “What continues to attract you to messing with reality?”

There is a ‘scrim of reality’ superimposed over a story which makes use of a trope oft-utilised by writers of children’s literature, actually: Hyperbole. The amount of change of this story is straight out of Cities: Skylines, a fast-forwarded timelapse of a town under construction. The scale of this construction is fantastical.

PERIOD

any time in living memory. This landscape ‘transcends the moment’. At the same time, this is clearly a world of c. 2013 (the time of publication). There’s even a mention of the iPhone. Phones always place a story specifically in time.

But does it stay 2013?

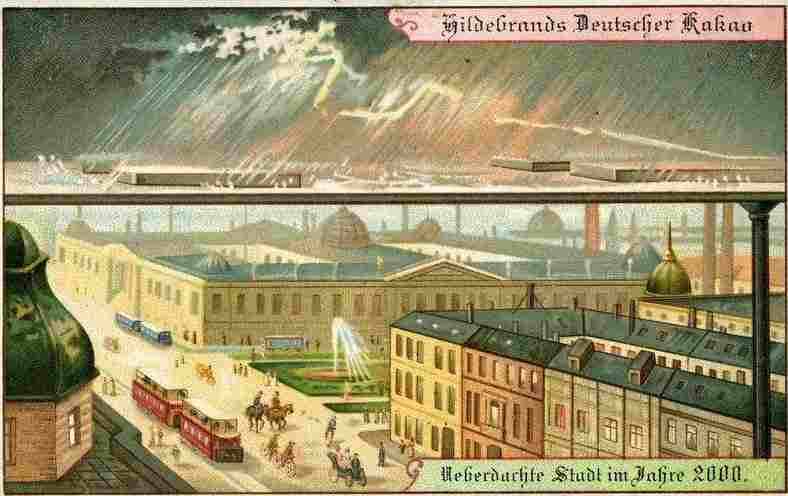

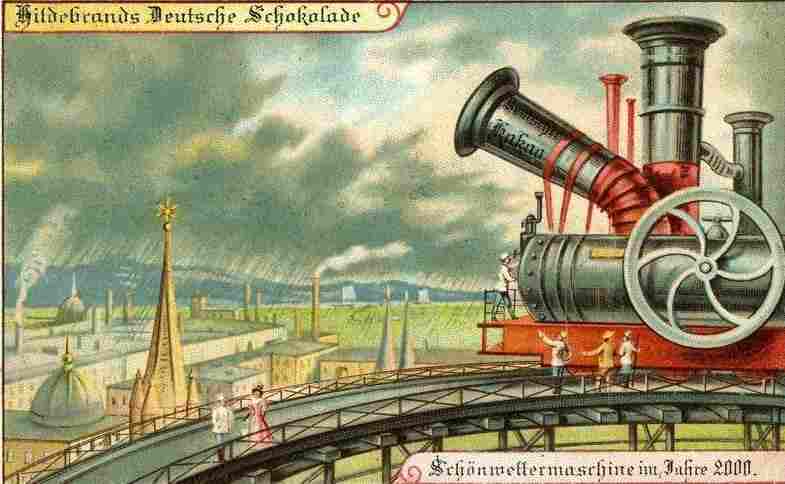

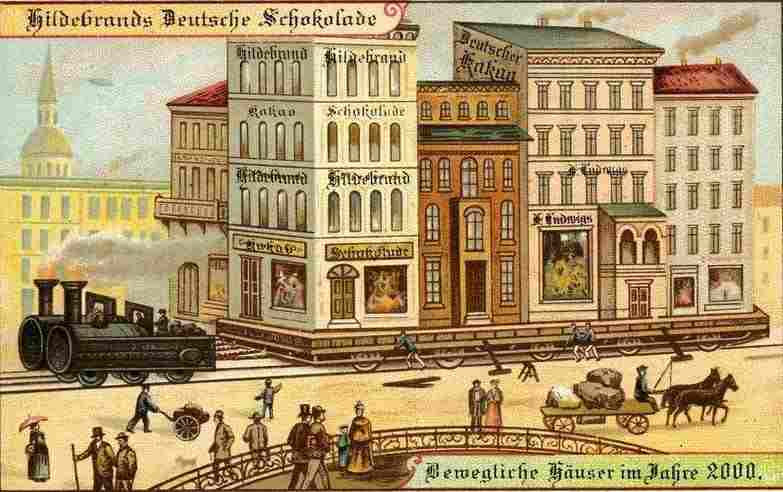

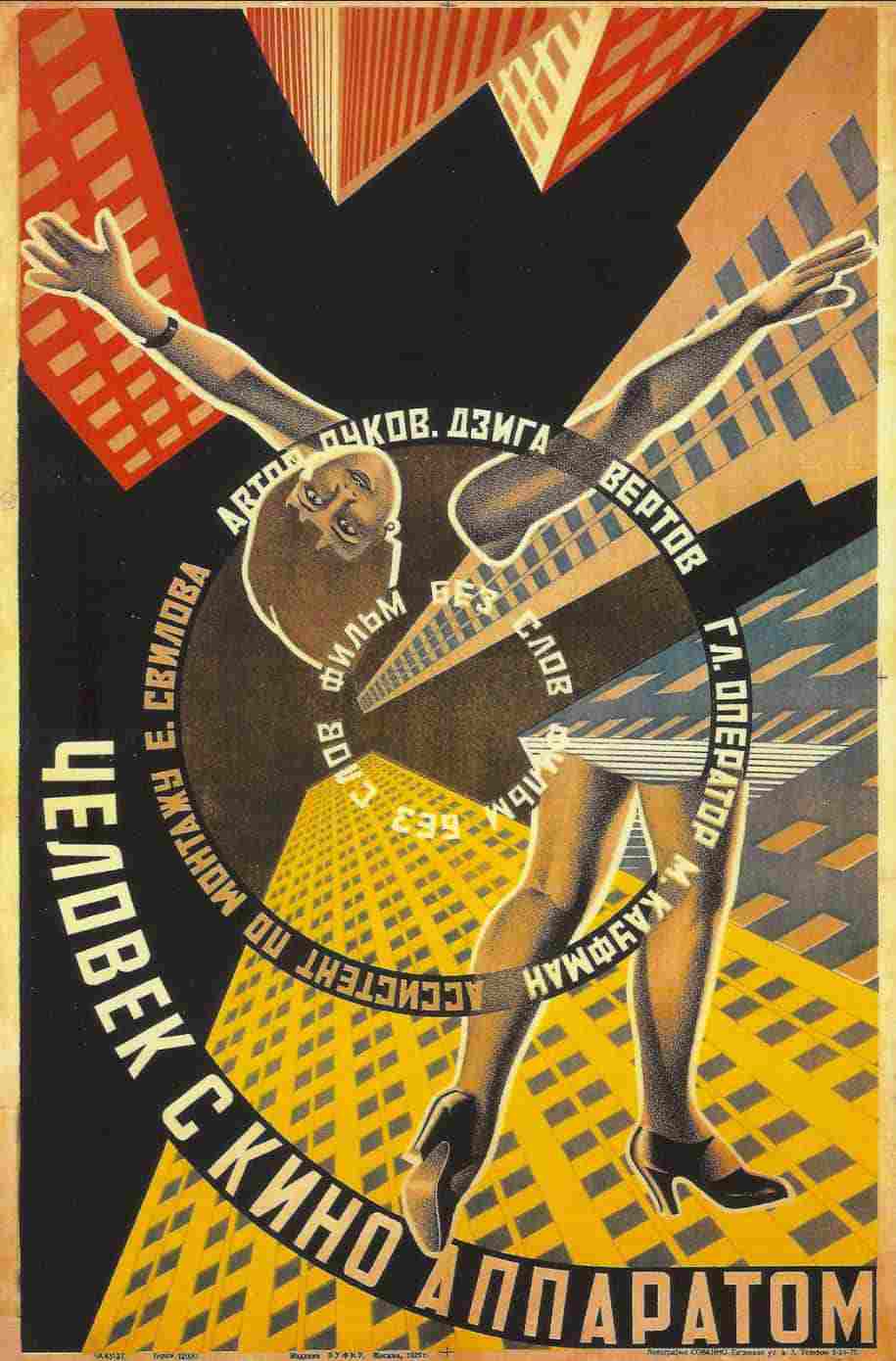

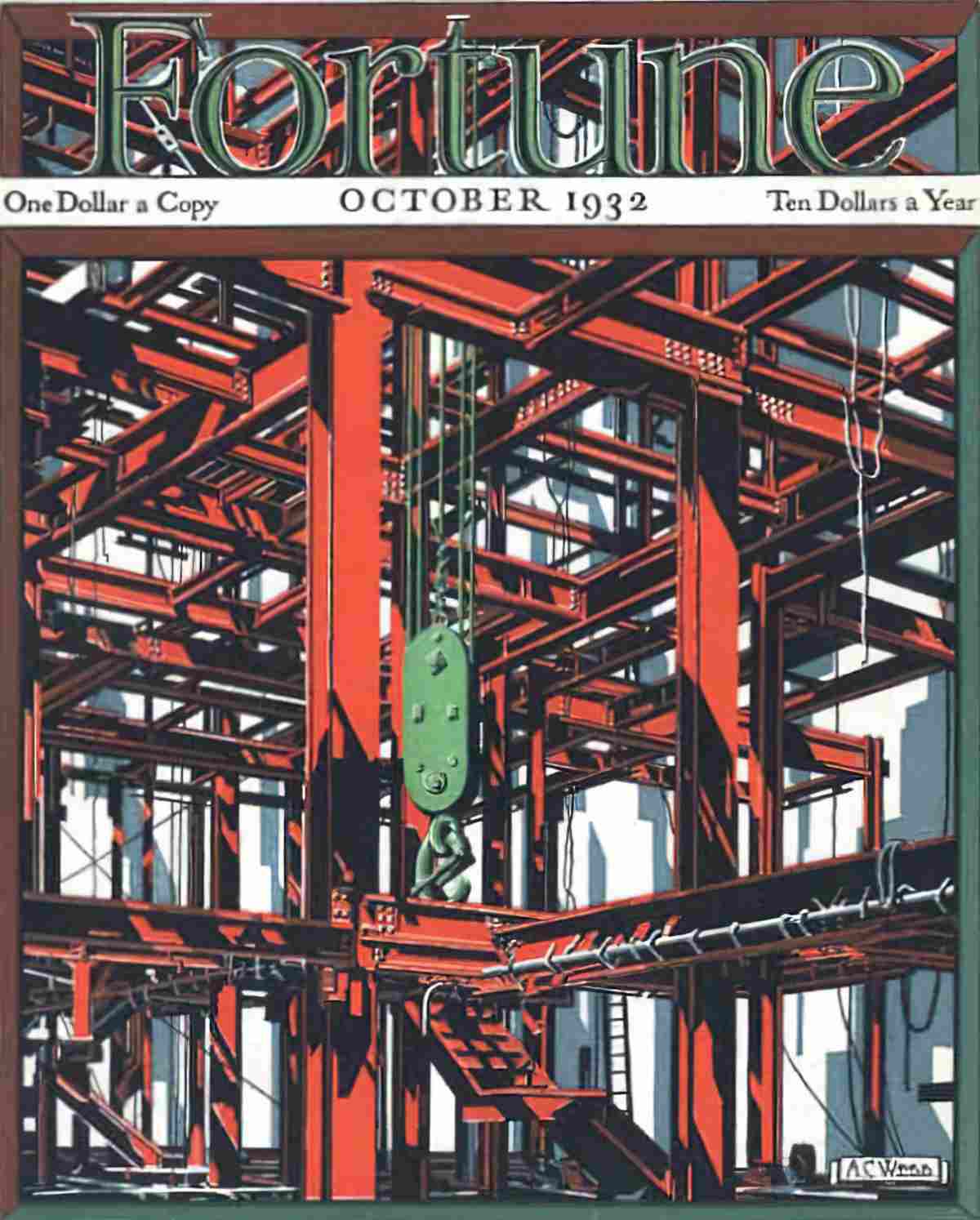

It’s interesting to take a look at how previous generations imagined the future, and what they were afraid of.

Here are some examples from around 1900. Can you tell which specific fears and hopes the illustrator was addressing?

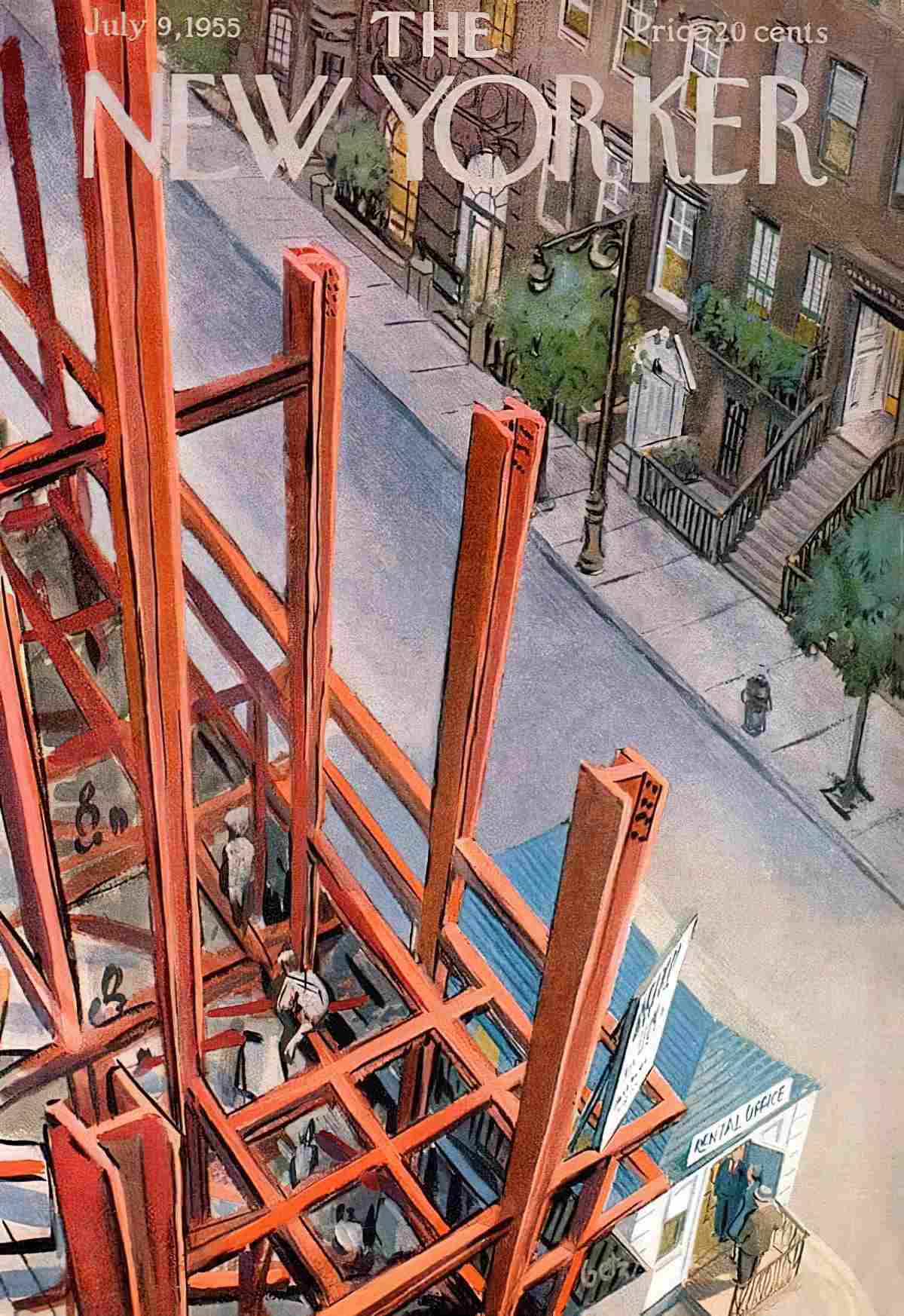

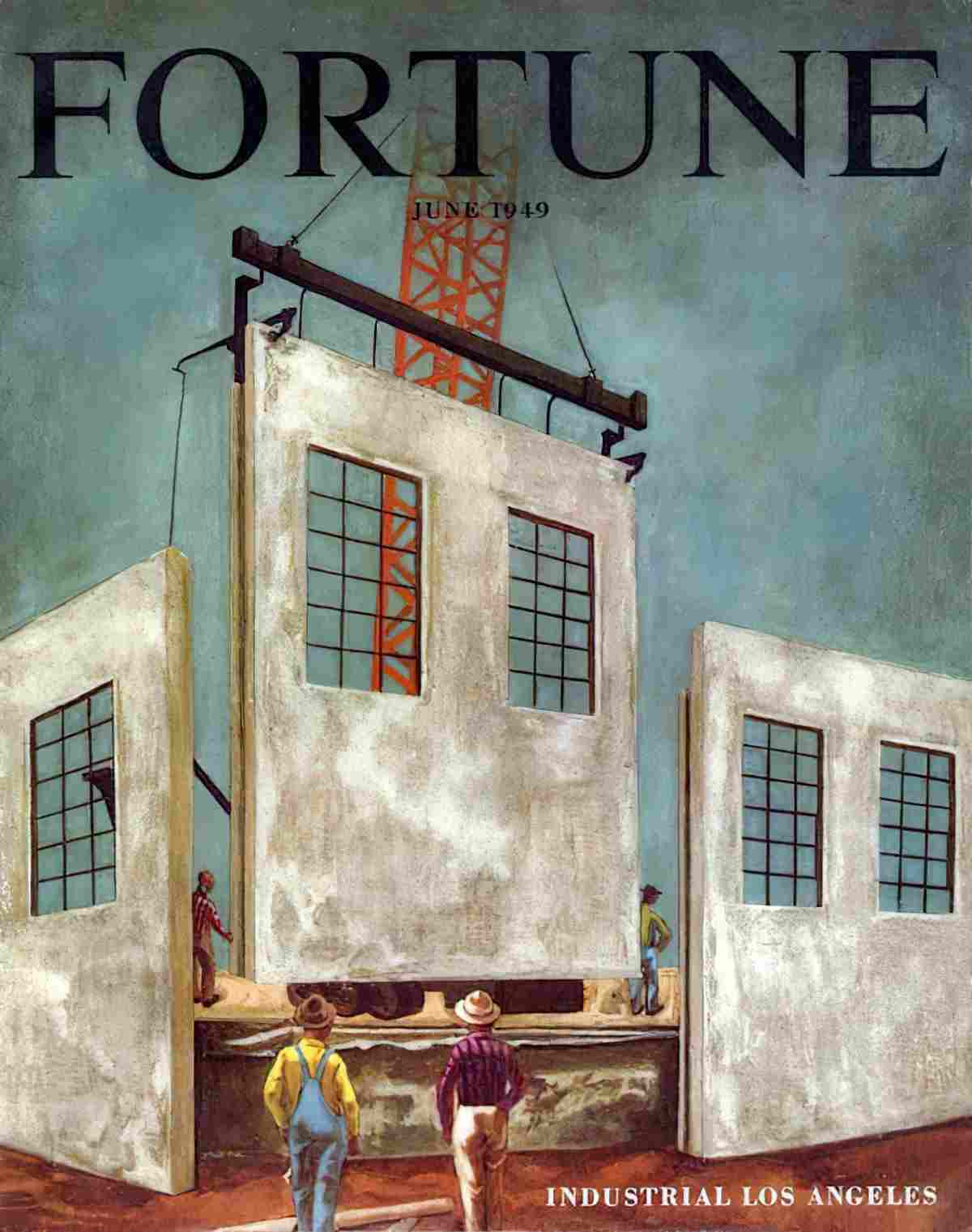

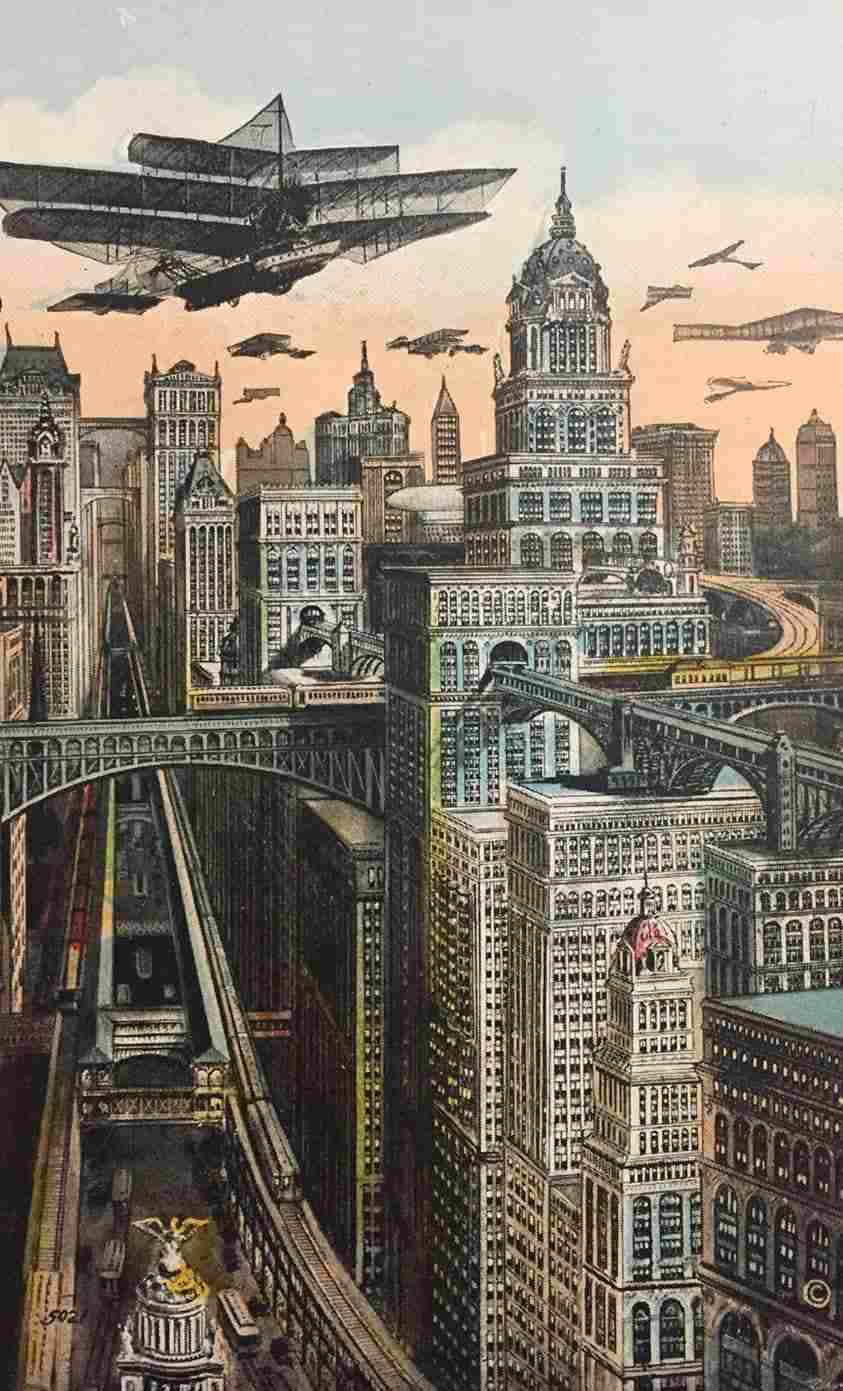

Fast forward a decade, and this is a postcard imagining the future of skyscrapers in New York.

Here’s a ‘house of the future’ illustratrated for a 1961 publication. It doesn’t look all that ‘futuristic’ now, does it? I can imagine a place like this exists. By 1961, people were imagining massive houses with curved lines, a lot of glass, a lot of space.

The old savings bank was still there, with its high front steps and its fluted columns, but it stood two stories taller and was connected to a new building by a walkway enclosed in glass.

“Coming Soon”

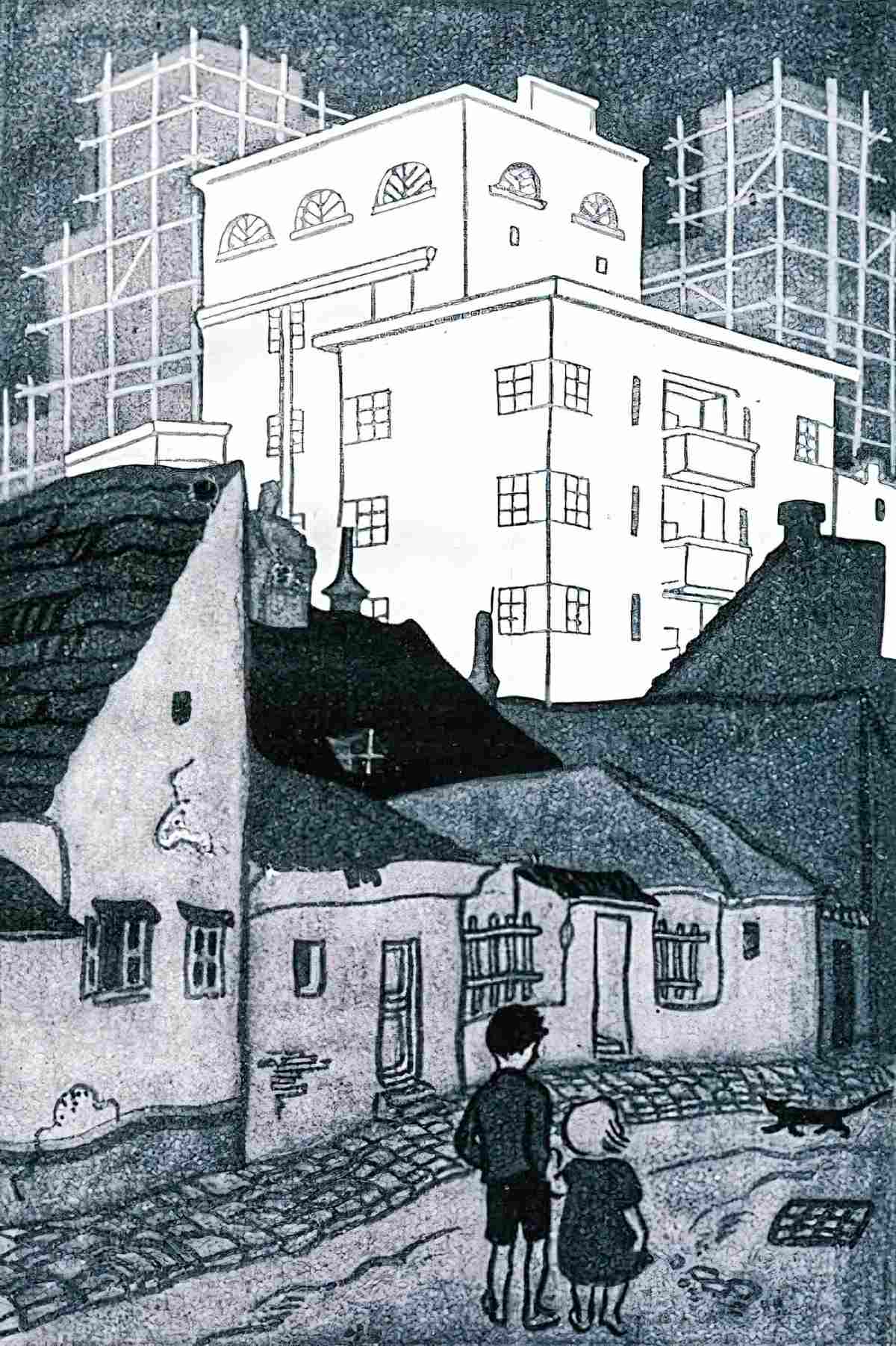

When imagining future cities, we have long imagined ‘big’. Humans scale down as the buildings scale up.

DURATION

unclear (by design). I believe this covers a man’s entire adult life, from the moment he left the city until he slips into (the possible dementia of) old age.

LOCATION

We are told right away that Levinson is a ‘refugee from the big city’, which establishes him as a character archetype. Chang-Rae Lee and Deborah Treisman recognise the city as New York, and say the small town could be any number of American places. It’s highly recognisable to them. This small town is also recognisable to me, from here in Australia. I’m thinking also of someplace I’ve never been: to the so-called ghost cities of China (Pudong, Chenggong District, Ordos City and around 50 other cities which have been built to boost the economy rather than to provide housing for the republic’s people.

The following sentence shows a deliberate non-specificity when it comes to location:

The old Vanderheyden Hotel looked like a Renaissance palazzo. The nail salon was a Swedish-furniture store.

“Coming Soon”

ARENA

Against reader expectation (we expect to go with Levinson to Miami, at least) we stay in the same little town across the entire story.

MANMADE SPACES

Oh yes, this story is all about the manmade spaces.

NATURAL SETTINGS

At the end there’s mention of forest but, in fairytale fashion, this forest is metaphorical.

The street came to an end; an unpaved path led into what appeared to be a forest.

“Coming Soon”

The forest is the subconcious. With the addition of details such as this forest, the reader understands that this town is not of the real world, even though he describes it ‘with great veracity’ (Lee’s phrase). Also, Levinson has until now managed to avoid entering his own subconscious by hyper-focusing on the world all around him. At the end of this story, this relatively comfortable state of being will come to an end.

WEATHER

The story begins in summer, with an al fresco coffee shop scene.

TECHNOLOGY CRUCIAL TO THIS PARTICULAR STORY

The story is full of the technology of construction. Cosmic horror gained traction when people’s minds were starting to be expanded by big, mind-blowing advances in science. The humans of the age of cosmic horror never got to see construction of the magnitude we see it today. What would Lovecraft have done with the ghost towns of China? (I don’t actually care, I’m not a fan of racists.)

LEVEL OF CONFLICT

This refers to the story’s position on the hierarchy of human struggles. We don’t know what’s going on in the wider world of the story because, like some kind of Groundhog Day plot, or perhaps The Truman Show, this character is fatalistically stuck inside his local environment.

He also points out that in any story the surroundings of the main character are both internal and external. We might consider this town an outworking of Levinson’s psychology. In which case, what’s going on with this guy? It’s ironic that he’s drawn out of the city because it’s too built up, yet it’s the construction aspect of his chosen town which initially invigorates him, because if things keep going like this, soon his small town will be no different from New York. How is it possible to enjoy the benefits of construction while also avoiding the inevitable consequence of it? It’s not possible. That, I believe, is the point.

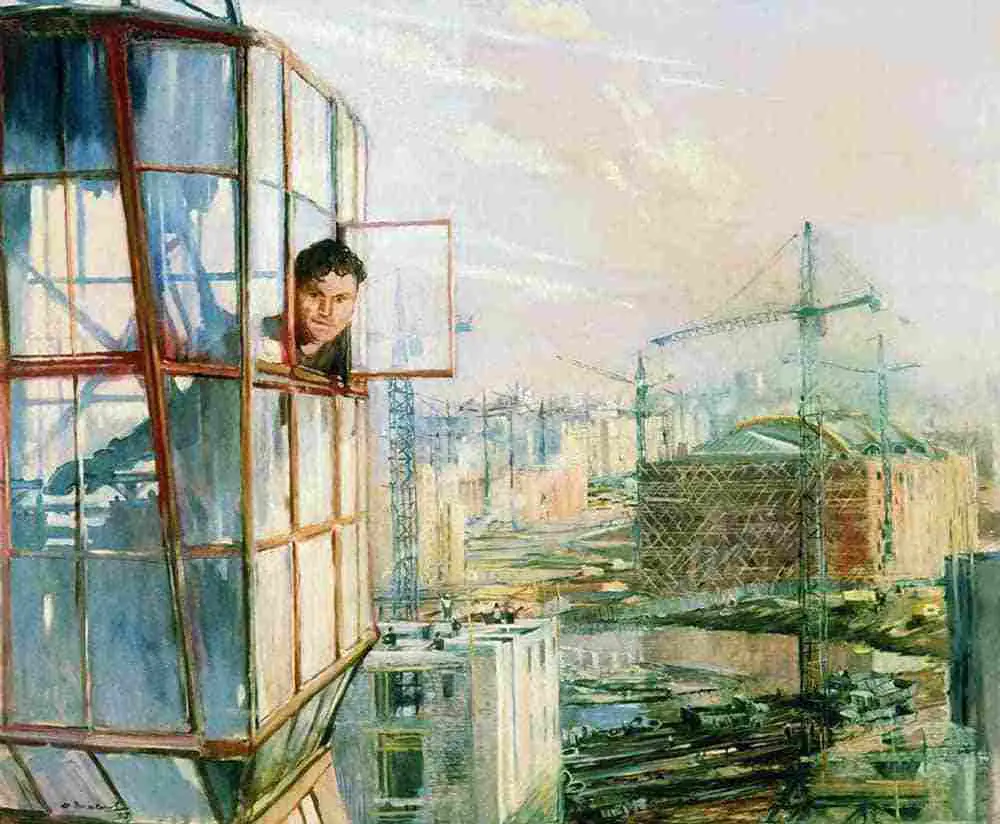

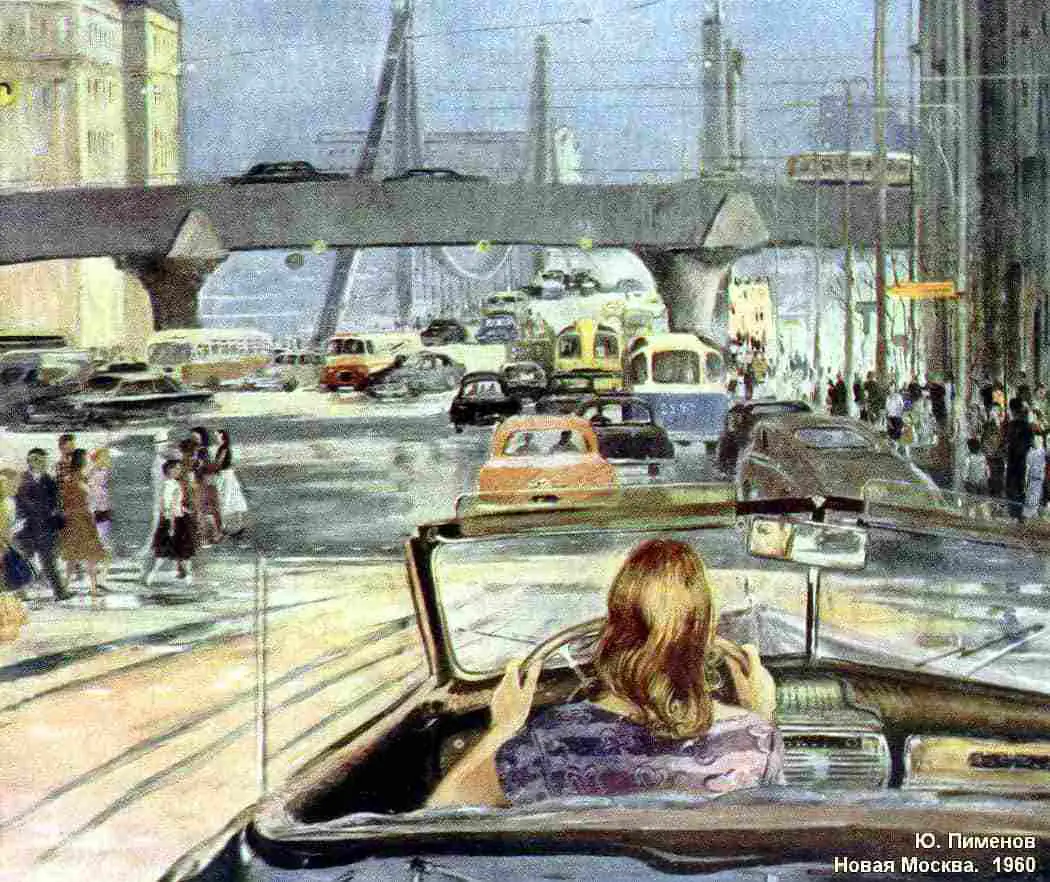

The paintings below, by Russian artist Yuri Ivanovich Pimenov (1903-1977), are a relatively rare artistic rendering of a landscape under construction, as witnessed by a painter who was able to see the wabi sabi beauty in such landscapes. These 1960s paintings accompanied the massive construction of residential buildings which had begun in Moscow. This construction effort saw the first appearance of “khrushchobs” (small apartments with a combined bathroom). For many Russians, the 1960s were a transition to a level-up in lifestyle.

If I’m thinking of Moscow and Australia while reading this American story, this speaks to the universality of setting. Millhauser has successfully created what feels like an atemporal town and a widely shared experience.

LEVEL OF REALISM

When does the switch from realism happen in this story? (The story world is never really ‘real’, but there is definitely a moment when the reader knows this world is screwy.)

Chang-rae Lee jokes that you always know when a character takes a nap that something will be different when they wake up. Millhauser mentions how time helps with this disorientation – Levinson has a dinner with friends at eight, but next thing we know, he’s back from Miami. We have no idea how much time has elapsed. This forces readers to do a double-take. We assume this happens on a different Saturday, but the story never says so overtly.

Millhauser keeps mentioning specific times: One Saturday afternoon in summer, Ten minutes later, 7:35, 7:55 etc. But the nature of time is that it happens every day. The next scene could be the same Saturday, or it could be a Saturday many years later.

Deborah Treisman asks if this is a Rip Van Winkle story. In Washington Irving’s short story “Rip Van Winkle”, a Dutch-American villager in colonial America meets mysterious Dutchmen, drinks their liquor and falls asleep in the Catskill Mountains. He awakes 20 years later to a very changed world, having missed the American Revolution.

But no, the fantasy time of a Rip Van Winkle story is clearly defined. Levinson in “Coming Soon” is not dreaming in his sleep; he is immersed in the ‘living, continuous dream’ which we all share.

STORY STRUCTURE OF COMING SOON

PARATEXT

I would like Chang-rae Lee and Deborah Treisman to have talked about the meaning of the title, but I’m left wondering, “What, exactly, is coming soon?” I’m left thinking it’s probably death. (Because aren’t all short stories ultimately about death?) Perhaps it’s just ‘overwhelm’ that’s coming for Levinson.

At a surface level, the title comes from this passage:

At the next street, he turned left toward Main. He had a clear view of the new sidewalk café, with its red fabric railing; next door, workmen were replacing brick with stone, under a sign that read “coming soon.” He had a confused sense, as he crossed Main Street, that the stores were no longer the same, that everything had changed again, but surely he was mistaken, an effect of overexcitement in the oppressive afternoon heat.

“Coming Soon”

SHORTCOMING

Cosmic horror says, “The mundane will cloud your view of reality. Pay attention and you’ll see what’s really there.” Like a cosmic horror character, Levinson ‘only belongs in this story’. For instance, Levinson wishes he’d been a civil engineer or a town planner. This is exactly the sort of desire and regret that matches a story about the construction of a town. Apparently Millhauser is a master of creating specific characters for specific settings/stories.

Levinson is a creature of habit, taking the same coffee, and the same route to the coffee shop every day. He could be a member of the Dull Men’s Club. This routine life juxtaposes against the massive changes happening all around him. He has to wave at the old lady on her porch. Routine and control of the environment calm him.

he turned onto West Broad and walked to the corner of Maplewood, to see how his construction site was coming along.

“Coming Soon”

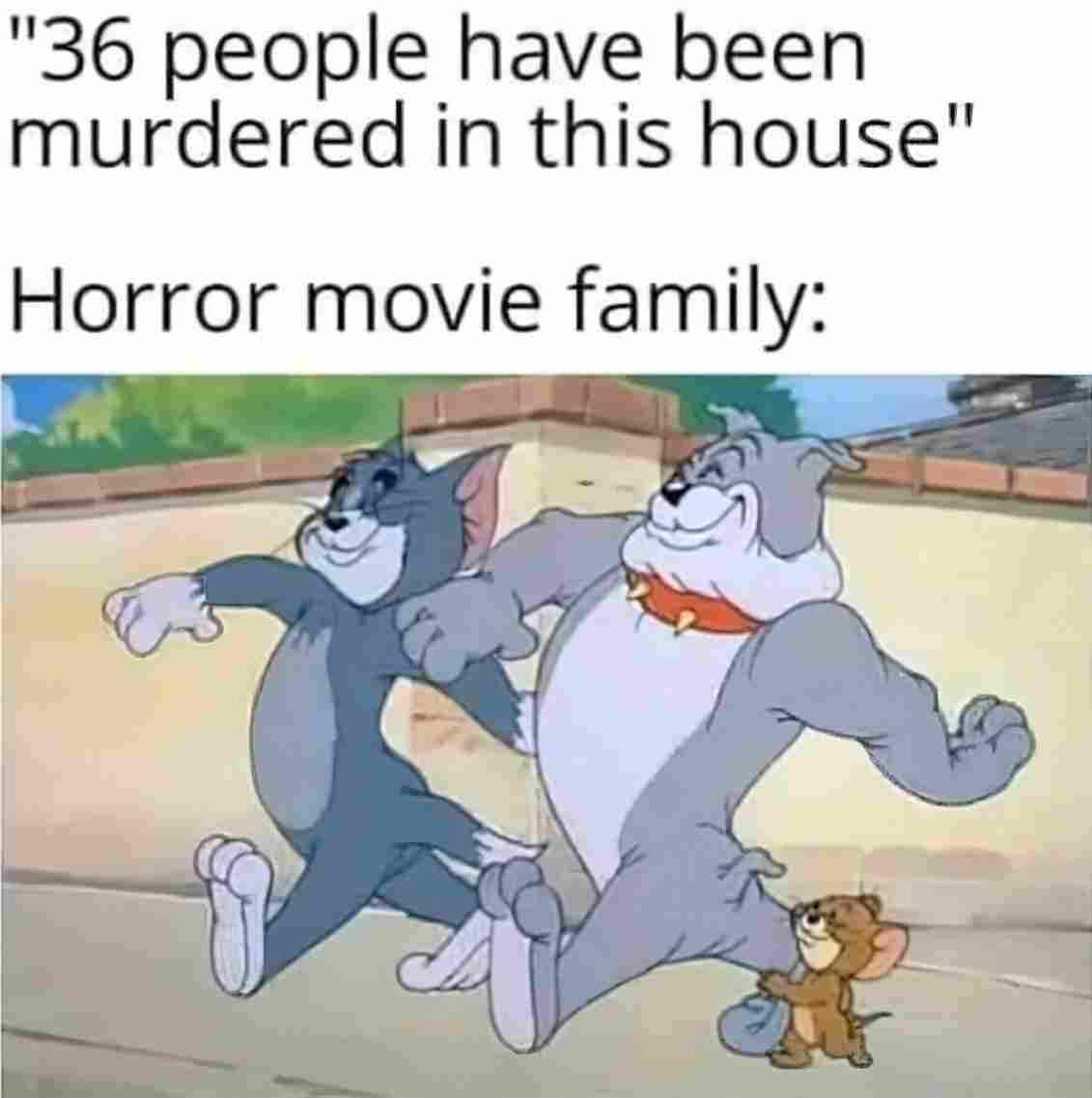

For the purposes of this story, routine equals fate. He’s almost robotic, the way he goes about his stroll along Main Street, drinking the same coffee at the same coffee shop, saying hello to the same old lady. Robotic behaviour can be funny, and it can also be horrific. (Horror and comedy genres share much in common. It’s bizarre.)

Levinson doesn’t want to live in a small small town. If the town is too small, it won’t be sufficiently well-managed for this guy.

Levinson is both attracted to and horrified by construction. Otherwise, he’s not a particularly individuated character. In the golden age of cosmic horror, characters were Everymen (who were often dead at the end anyway, so who cares). These early cosmic horror characters had no individuating characteristics at all.

Modern audiences want a bit more from a main character than a walking set of clothes. We need just a few details to help us imagine a real character, and Millhauser gives us just enough in this story to achieve verisimilitude but withholds the idiosyncracies which might make us think of Levinson as a real individual . Compared to the language used to describe the city, Millhauser’s thumbnail sketch of Levinson is conveyed in remarkably unadorned language:

He’d put a down payment on a shady house on a quiet street of overarching maples, but he hadn’t kissed the city goodbye in order to sit back with his hands on his belly and live a soft life. He still worked as hard as ever, often staying at the office till six or seven; on weekends, he mowed his lawn, caulked his windows, cleaned his gutters, shovelled the drive. He was seeing two women—dinner and a movie, no more—while waiting for the right one to come along. He had a decent social life; the neighbors were friendly. He was forty-two years old.

Coming Soon

Notice the phrase ‘shady house’. Shady, of course, has two meanings: Either nicely shaded by leaves, or horrific/creepy.

SPATIAL HORROR

Now to the very interesting example of mise en abyme as spatial horror.

On one corner, the sidewalk was closed to pedestrians; beyond a portable chain-link fence, a small white house with a red roof stood entirely enclosed by the studs, beams, and rafters of a much larger house, which was being constructed around it. Levinson tried to imagine what would happen to the original house—would it remain inside, a house within a house?

“Coming Soon”

In an episode of Breaking Bad, Walt and Jessie cook meth inside houses which have ostensibly been set up for pest control. The outside of the house is covered in a huge canvas tent while something unexpected and dangerous happens underneath. There’s an inherent horror to the idea that something can invade our homes from the inside.

On A Clear Day (The Peddlars) on YouTube

This also explains the popularity of Bad Nanny stories, about women brought into the fold to help run the house, but who end up destroying the family unit. In stories for children, Monster House is a horror example of the ‘house that comes alive (from the inside)’.

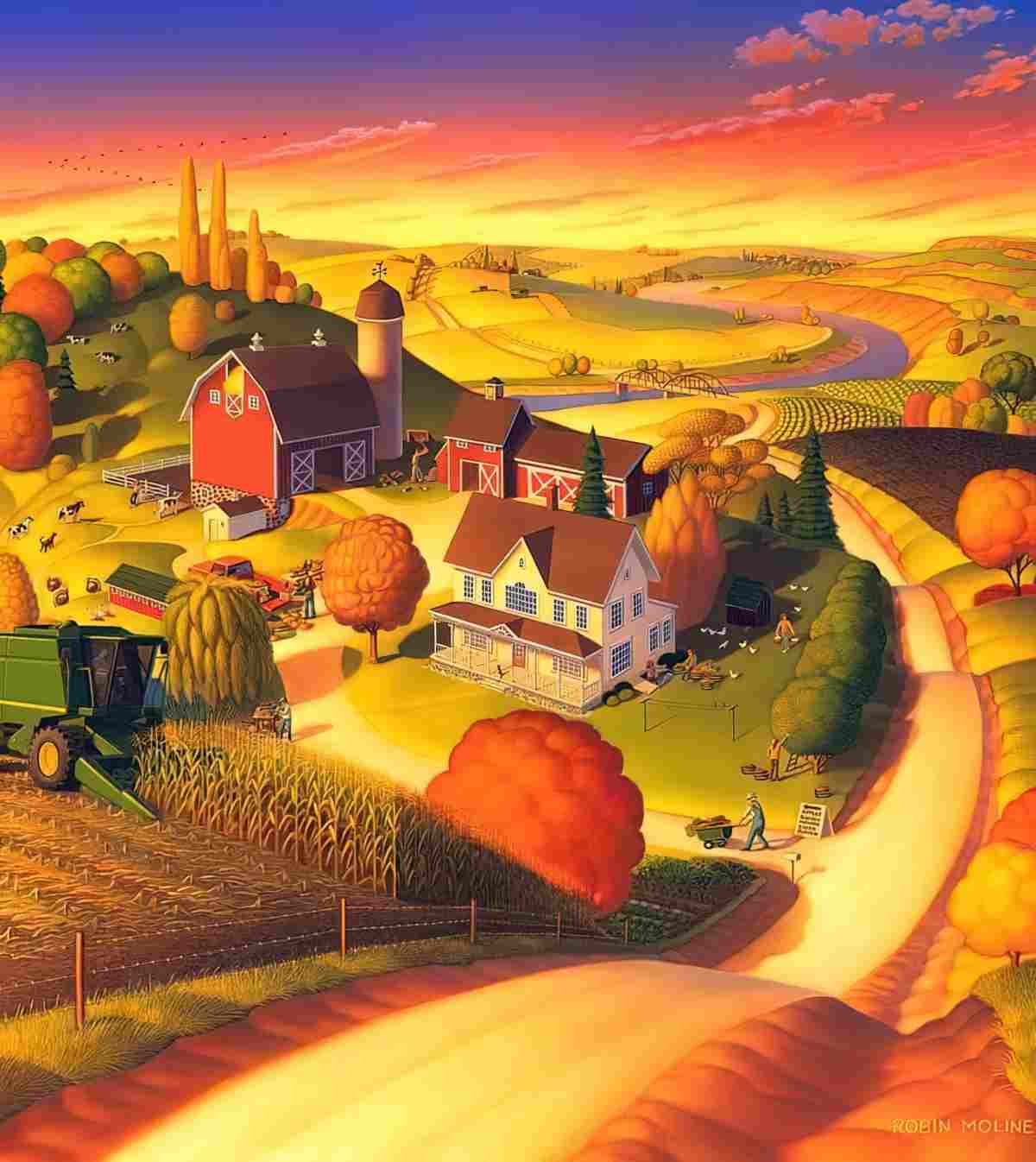

There’s something inherently horrific about the mise en abyme effect (achieved by holding two mirrors facing each other). Human brains can’t deal with the concept of infinity, so that’s probably part of it. But also, the idea of ‘things within things’ all the way up — and down — promises there’s more to a setting than meets the eye — snail under the leaf, but on steroids. Mise en abyme promises, cosmically, horrifically, more than we can ever possibly know. Hence, mise en abyme as horror trope. The house within a house of this particular story is extra horrific because of the original red and white colours of it, which we tend to associate with cosy neighbourhoods, hence the classic red American barns and white picket fences.

This town has been created by humans, but is slowly taking on a life of its own. This horror works similarly to the old Ghost in the Machine trope, in which humans create the computer. The computer achieves consciousness and kills us all.

DESIRE

On weekends and evenings, whenever he was free, Levinson liked nothing better than to explore the streets of his town.

Coming Soon

Levinson is more interested in architecture and construction than in people. People do not occupy his mind. He’s even dating two women. Rather than demonstrating an insatiable appetite for connection which cannot be satisfied by one woman, in Levinson’s case we have the opposite: To him, one woman is the same as any other. The woman he’s waiting for exists only in his imagination. So long as he imagines the perfect woman, he can justify remaining single in an amatonormative world. Anyhow, little is said about that. Just when you think the story might be about the messiness of dating two women at once, it is not. We never hear more about the women.

So what does Levinson want at a deeper level? What human need is he satisfying by wandering the streets looking at all this construction?

OPPONENT

Since the city itself is a character, the city itself can function as Levinson’s story-worthy opponent. The defamiliarised city, replete with various examples of spatial horror, begins to scare him. It almost feels as if he is losing his mind, and he may be. He is the town; the town is his mind.

Chang-rae Lee says that ‘all writers do this’: Presenting a reality which seems fine, or ‘fated’, then following this with something which upsets that illusion of fate (proving it was all an illusion). (Do all stories do this? That’s an interesting question.) Certainly all horror stories do.

The happy/utopian setting before shit hits the fan has been called ‘Snail Under The Leaf’. Meaning, everything seems fine until you lift a leaf and find a gross little snail under it. We might liken this switch that happens in lyrical short stories to the switch from the iterative to the singulative that often — but not always — happens in children’s books. (Every day, Johnny would… [ITERATIVE] But one day…[SINGULATIVE])

PLAN

Like your typical cosmic horror character, there’s no plan here, apart from reacting to events as they play out. Levinson has already made his major life decision: Moving from the city to a small town for lifestyle reasons. Now he gets on with the day-to-day job of living, and maintaining his house.

I’ve heard commentators in Australia saying lately that homeowners are spending a lot of money on their houses and that’s why it’s impossible for a young buyer to get onto the property market. There are no cheap-ass houses to be found. I’m no economist but I think there may be a bit more to the housing crisis than that. Still, in light of this story, it’s an interesting point of view. Are we overcapitalising on our houses? I mean, there are other issues apart from economy ones, like thousands of people sending old kitchens to (not) decompose in landfill.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

How does this story build to some sort of climax? Readers expect some sort of build, after all.

The world becomes less and less familiar until it feels completely different and not at all like ‘home’. The climax is when Levinson runs out onto the highway and catches a ride out of there. I see this as a kind of death — if not literal, then spiritual.

there was only so much you could take in before exhaustion struck you down

“Coming Soon”

The home is such an important place for humans. Even for nomads, there must be some place where basic needs are met. Without the concept of home, we cannot exist.

A note on the plot shape of this story: Scenes repeat, and each time we see the scene again, it contains more: more detail, more horror, in this case. “Coming Soon” is an example of a cumulative story. A standout example of this plot shape (which doesn’t take long to read) is “The Fifth Story” by Clarice Lispector.

ANAGNORISIS

Back to the mise en abyme, Chang-rae Lee and Deborah Treisman wonder if along with the house within a house, if there might be a man within a man, too. Is this one way of showing character change? On the page, the reader is not shown any character change. Partly this is because this story avoids interiority. The word used by Lee: details are ‘funneled’. We see Levinson only from the outside. We are shown only what he observes.

In the podcast, a distinction is drawn between Cheever’s “The Swimmer” and “Coming Soon”. “The Swimmer” by John Cheever features a tragic character who has no understanding of what’s going on. With Levinson this is not the case, they say. He seems to know what’s happening around him.

I’m not sure this is true. For me, this story is a metaphor for dementia. If you’ve ever spent time with someone with dementia you have witnessed the disorientation which seems to come out of nowhere when they’re out and about, even in familiar places. “Where am I?” they might suddenly exclaim. “Which way is home?” Then, slowly, any interiority which was there gradually disappers over time, until all that is left is a world which seems to be changing at a fantastical rate, and where the once familiar now looks unfamiliar.

When he reached the tree-lined streets at the outskirts of his neighborhood, he realized that he must have made a wrong turn somewhere, for he was passing houses he had never seen before, though some seemed dimly familiar.

“Coming Soon”

NEW SITUATION

Like many lyrical short stories, this one ends in medias res.

all at once Levinson found himself on a six-lane highway, where ruby tail-lights rushed away into the distance. On the other side of the divider, yellow headlights came streaming toward him. Under a blue-black sky, Levinson entered the second lane, passed below a sign with a name and exit number he did not recognize, and rode off into the night.

“Coming Soon”

Lee and Treisman, as I did, took special note of the word ‘rode’. He didn’t ‘run’ or ‘drive’ off into the night, but rode. However, my take was the inverse of theirs. For them, ‘to ride’ is to suggest he’s taken control of the situation, but for me, the fact that he ‘rides’ rather than ‘drives’ means he is being carried off, as if by the Erl-King.

As mentioned already, I think Levinson’s dead now, but then I do read death into everything. Perhaps he lost his grip:

Soon he was sitting in the shade of a table umbrella, drinking an iced cappuccino and trying to get a grip on things.

“Coming Soon”

But if I read this story at a metaphorical level, it is clear that Levinson is not getting out of this town (unless he is dead). The bars/frames/lines running through this story work like a motif suggesting a jail from which Levinson cannot escape. Look for passages like these:

A man with an orange stripe across his jacket was waving him to the right, where a narrow lane ran between back yards.

“Coming Soon”

As well as ‘jail’ and imprisonment, the lines might indicate a life segmented into parts — parts which he can never get back. When he awakes in the disorientation scene, the sunlight creates a ‘slash’. What has been slashed here? This is violent imagery, and suggests a definitive ‘line’ between what was before and what is to come.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

CITIES AND THE SELF

Chang-rae Lee and Deborah Treisman agree that in Levinson’s mind, he is the self-appointed officer of all this construction and renovation. Watching it all happen allows him to be, in a strange way, human.

To what extent do we derive our humanity from the settings we construct around us?

WHAT IS PLEASURE?

Lee and Treisman mentioned that the word ‘pleasure’ comes up a number of times. We don’t hear about other types of pleasure e.g. of visiting his mother or about any pleasure derived from dating. There’s no intimacy with another person. He is in solitary confinement of his own choosing.

IS THE FUTURE REALLY ‘BIG’?

How big can towns get before they start to destroy us (personally and collectively)? Though we imagine bigger houses when we imagine housing of the future, the reality has gone in the opposite direction. Only the wealthy can afford large houses.

RESONANCE

Why has Millhauser created for us a defamiliarised town which also feels super familiar? Interestingly, Chang-rae Lee found himself wondering what he’d been doing with his days, and I also had this reaction. Where have the last 14 years gone, I wondered, as I thought back to when we first moved into the end of this semi-rural cul-de-sac, now a suburban street corner. Every day looks the same but different.

What have I been doing with my time?

I was listening to Jonathan Storment yesterday, and something that he said really caught my attention. He talked about how we can spend hours of our day, months of our lives, pursuing things that in the end have no value. He gave the example of his obsession with the Rat on a Skateboard game on his smart phone. Jonathan was so proud when he figured out that he was ranked number 37 in the world on Rat on a Skateboard, but the more he thought about that, the more uncomfortable he became in realizing how much time he must have spent on this silly game. On thinking over our tendency to be distracted from worthy pursuits by trivial ones, Jonathan said, “The worst thing that you can do with your life is not to fail, but to succeed at something that doesn’t matter.”

Dr. Jennifer Shewmaker

I read somewhere that if you want to make the years seem longer in hindsight, punctuate them with memorable events. Since I despise big gatherings and all forms of event planning, I’m unlikely to ever take this advice, but I do think there’s some truth to it.

This circles me back to the point of cosmic horror: Whatever humans ignore is actually the most important thing. Are we so busy living our routine lives that the years are slipping by without us properly ritualising them? Honestly, this is one of my greatest fears.

Thanks, Mr Millahauser. Yes, thank you for this modern horror story. You got me.

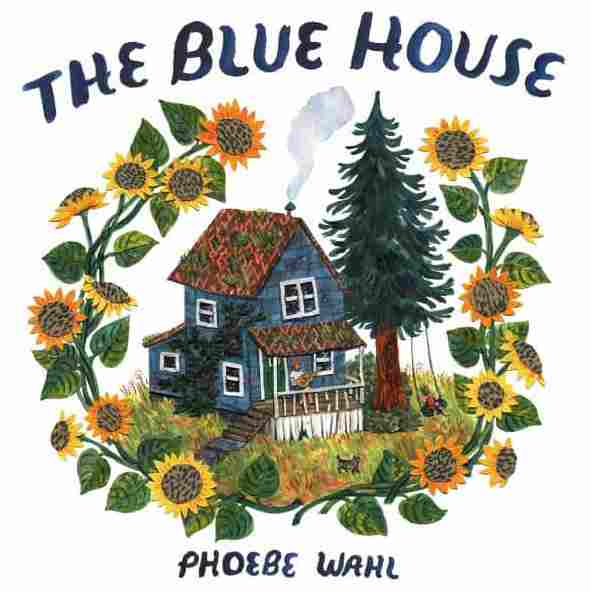

In the tradition of Virginia Lee Burton’s The Little House comes a heartfelt story about a father and son learning to accept the new while honoring and celebrating the old.

For as long as he can remember, Leo has lived in the blue house with his dad, but lately the neighborhood is changing. People are leaving, houses are being knocked down and shiny new buildings are going up in their place. When Leo and his dad are forced to leave, they aren’t happy about it. They howl and rage and dance out their feelings. When the time comes, they leave the blue house behind–there was never any choice, not really–but little by little, they find a way to keep its memory alive in their new home.

The header illustration is by Derek Roberts. I believe it is a jigsaw puzzle.