Different cultures view the sun differently. Ask a Western child to draw the sun and they will draw it yellow. Ask a Japanese child to draw the sun and they will draw it red.

Our closest star is ‘actually’ white. I grew up in New Zealand and I drew it yellow. But when I lived as an exchange student in Japan, I noticed the sky really ‘is’ red. It’s fully red. American children also colour the sun yellow.

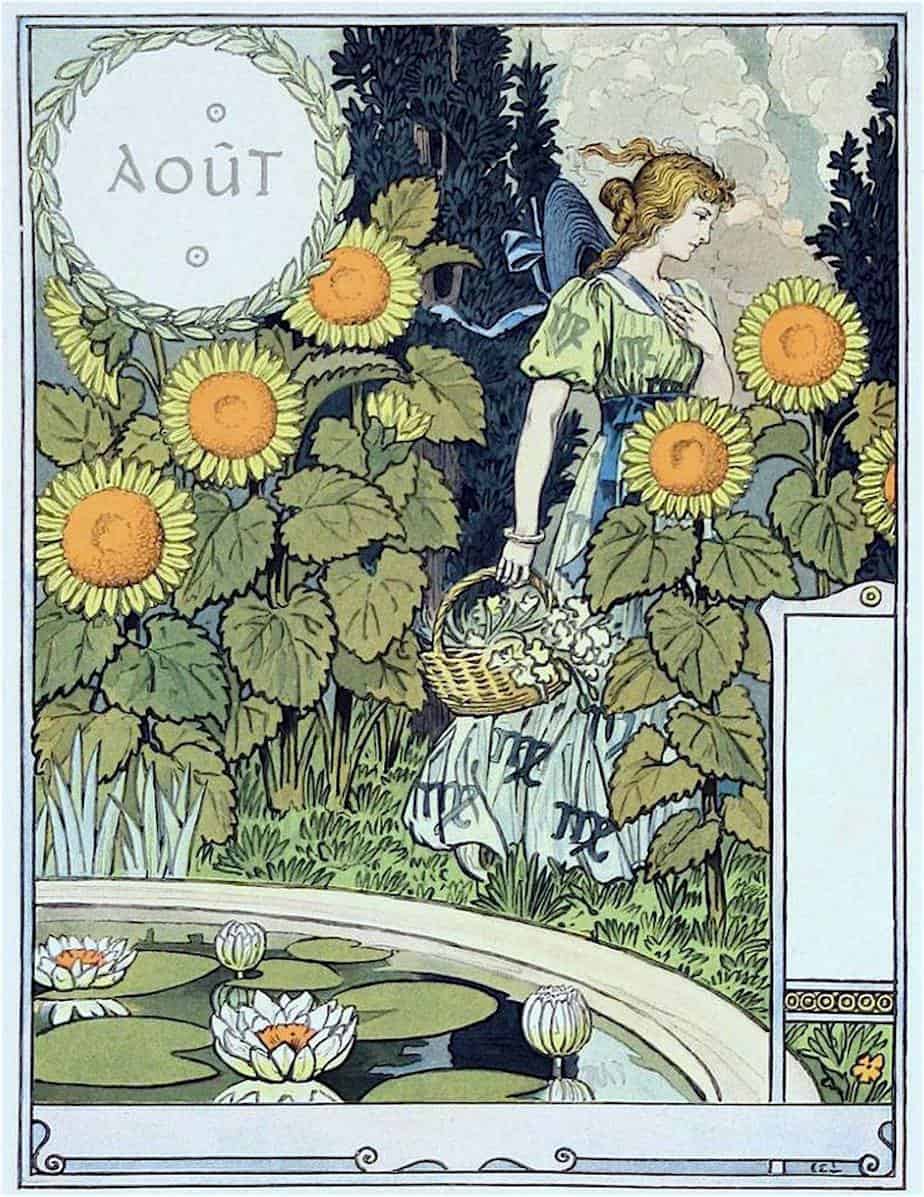

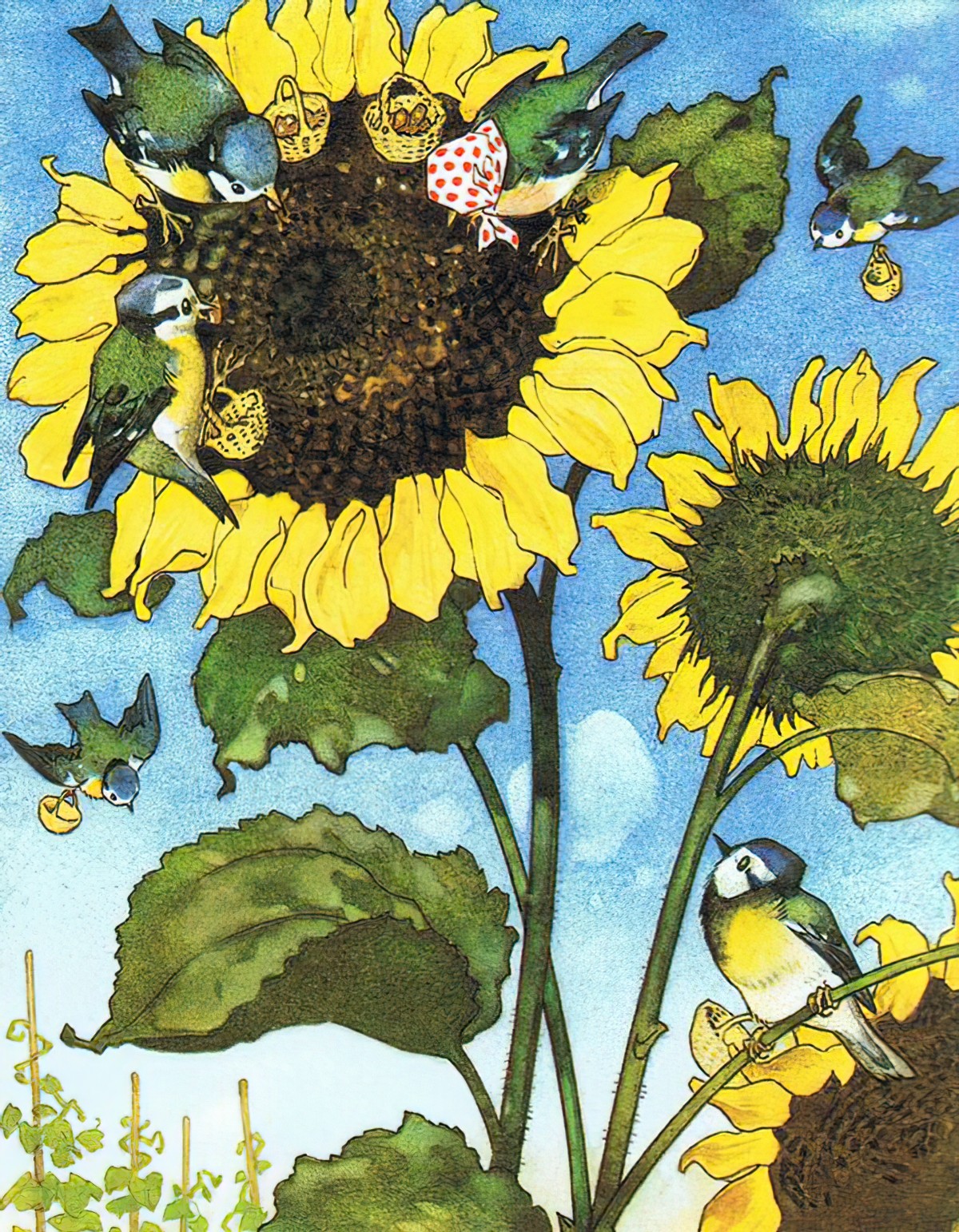

(The sunflower must have been named by someone who thinks the sun is yellow.)

However, it doesn’t always look bright red in Japan, and it doesn’t always look bright yellow in my Western home countries, either. In photos it appears most often as white. Part of our understanding of ‘an object’s actual colour’ is acculturation. We grow up learning that the sun is a certain colour.

Part of learning to illustrate is learning to really see. Wherever you come from in the world, suns, skies, road surfaces, and of course human skins, come in all different colours.

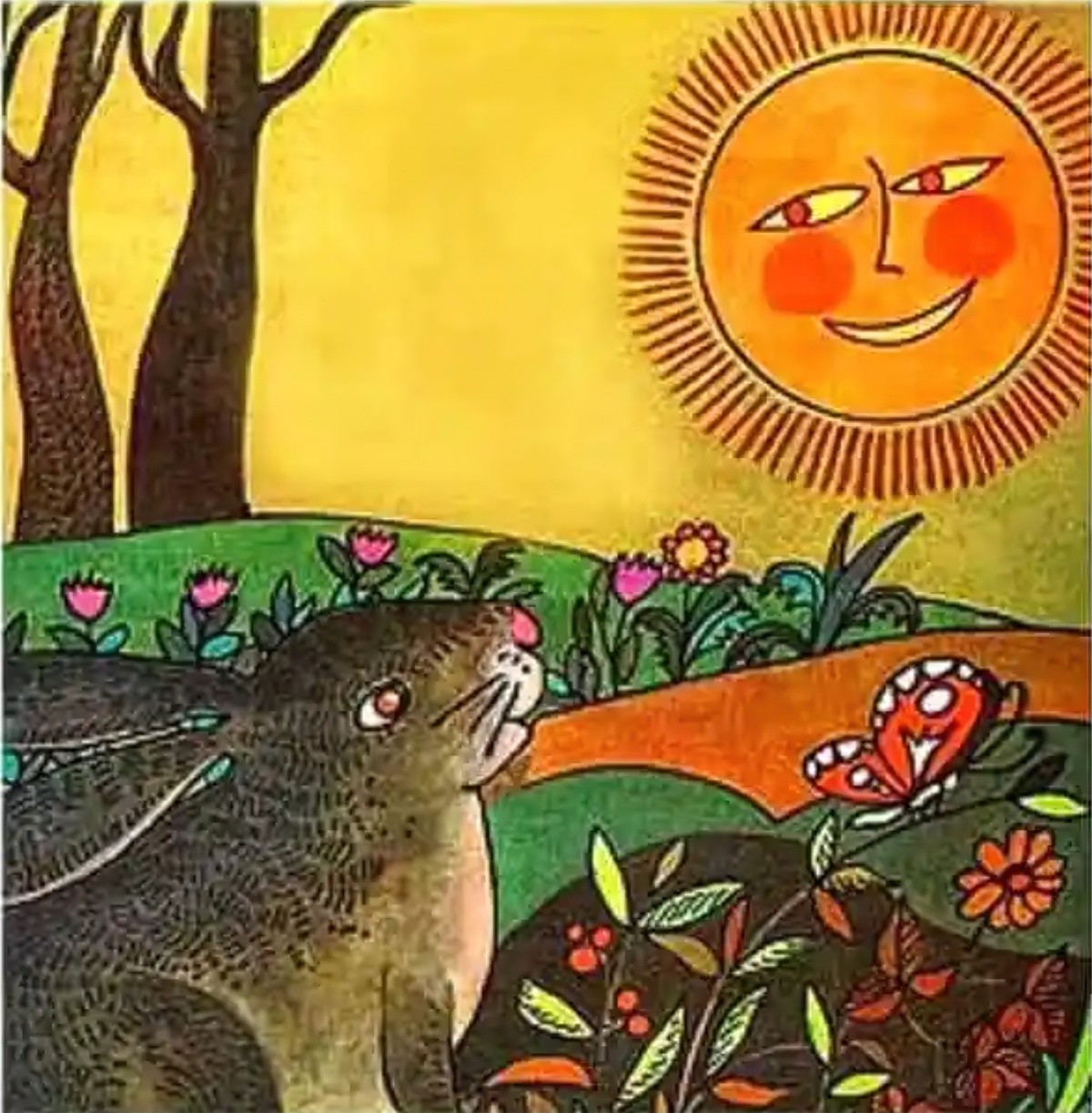

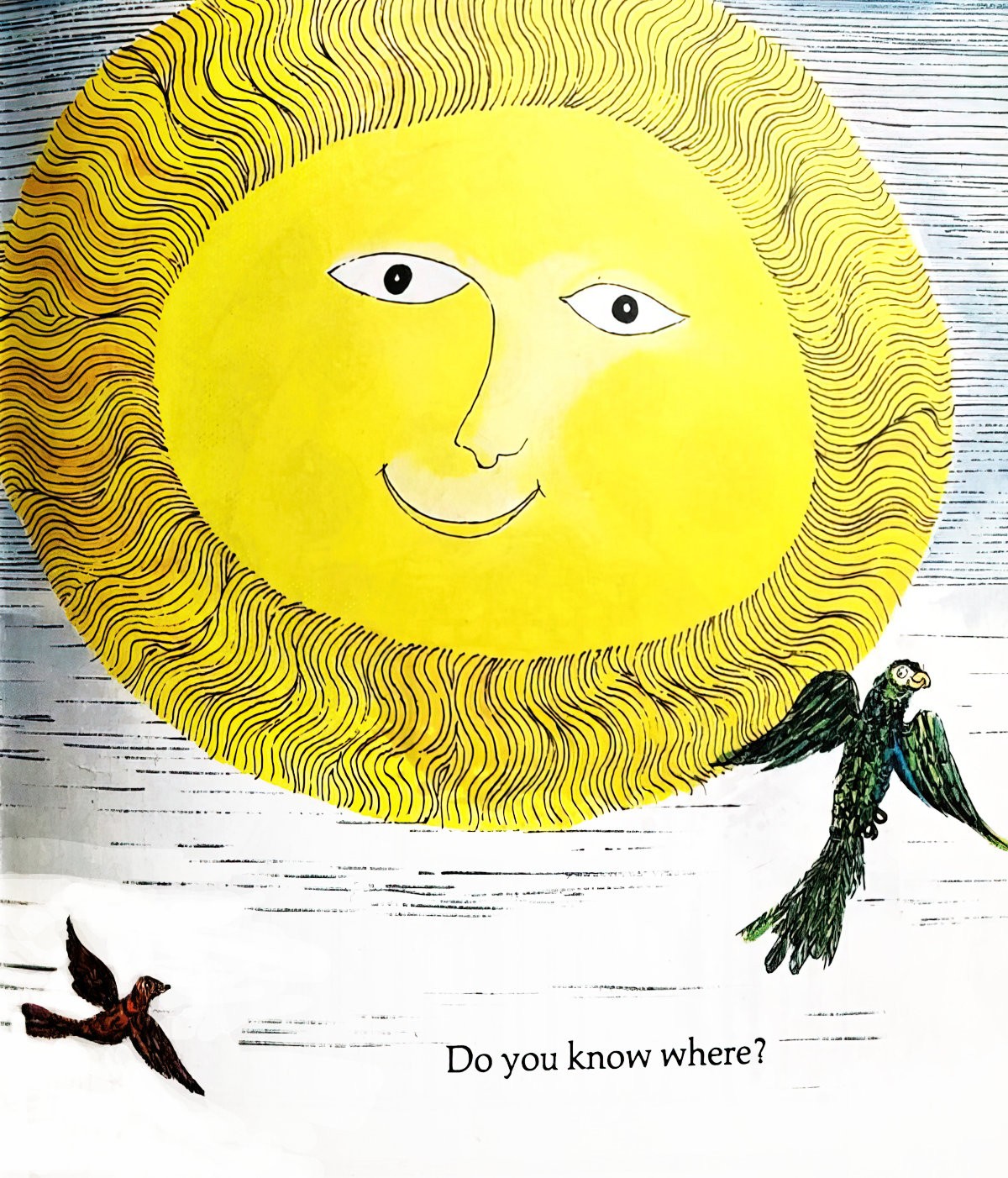

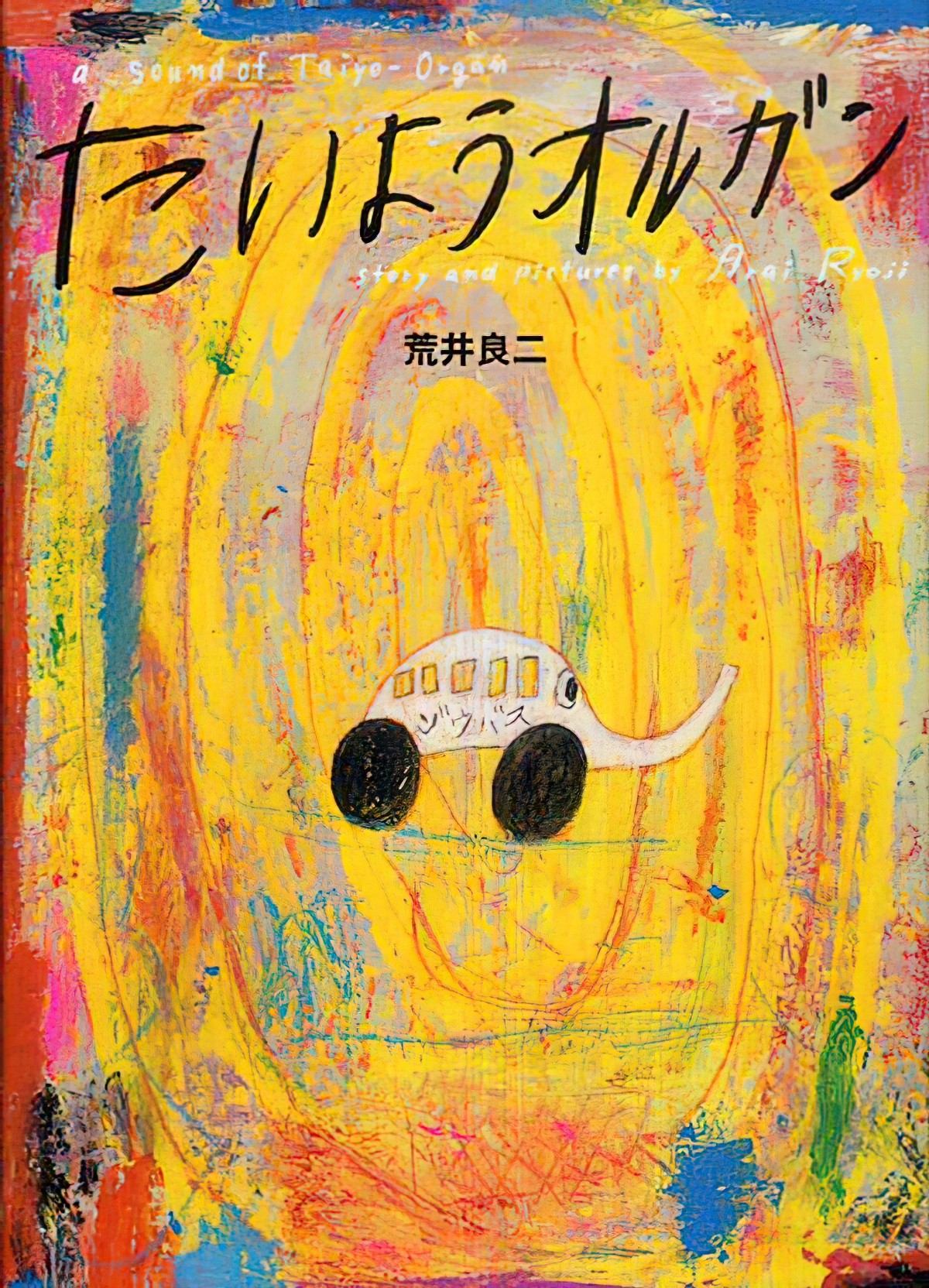

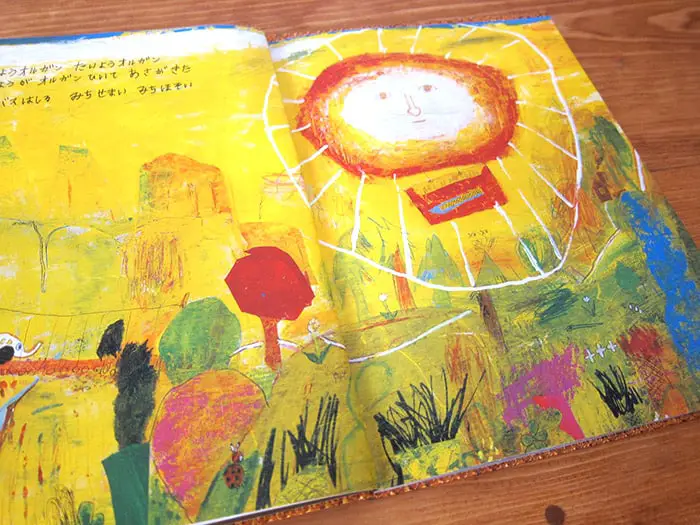

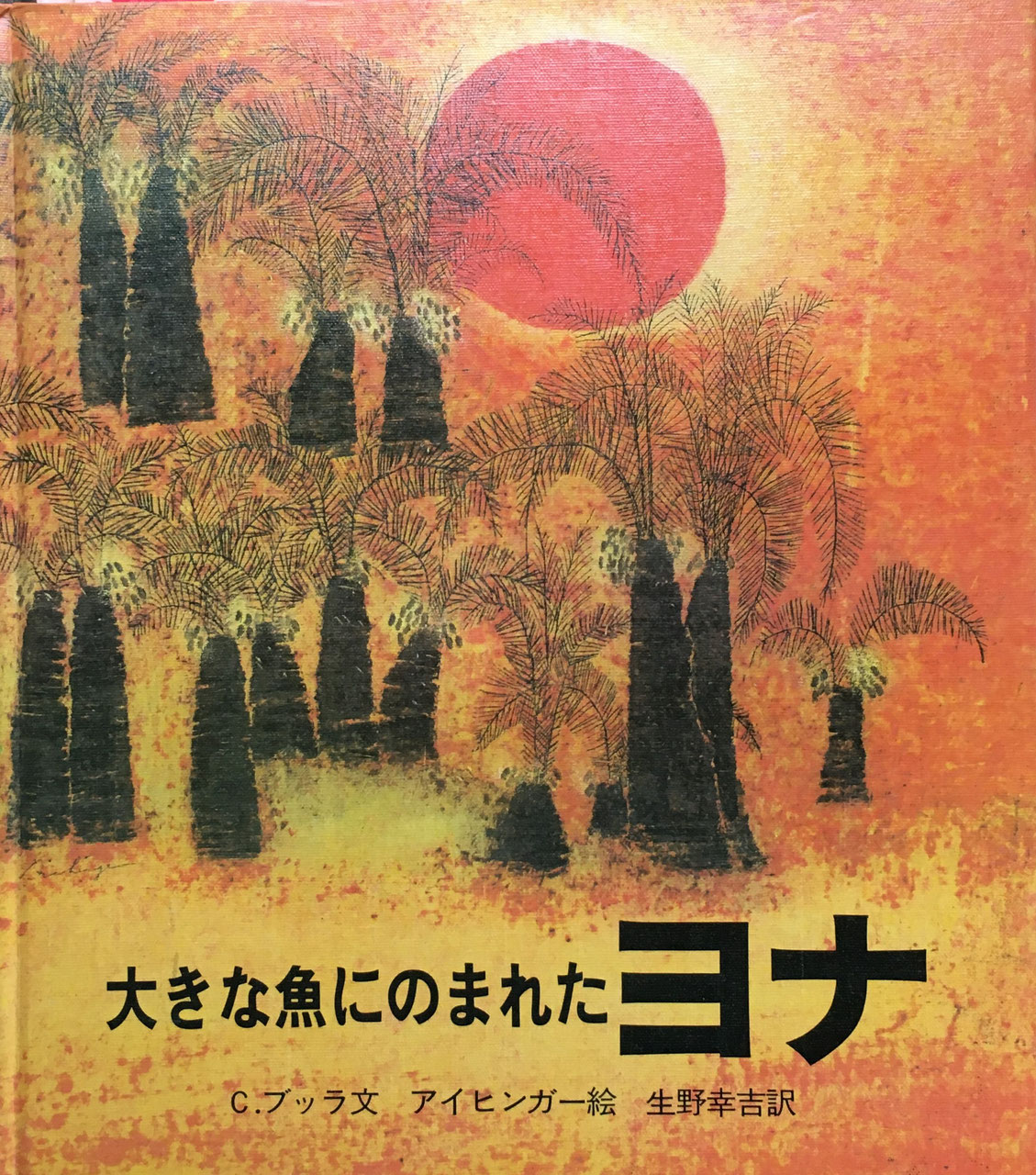

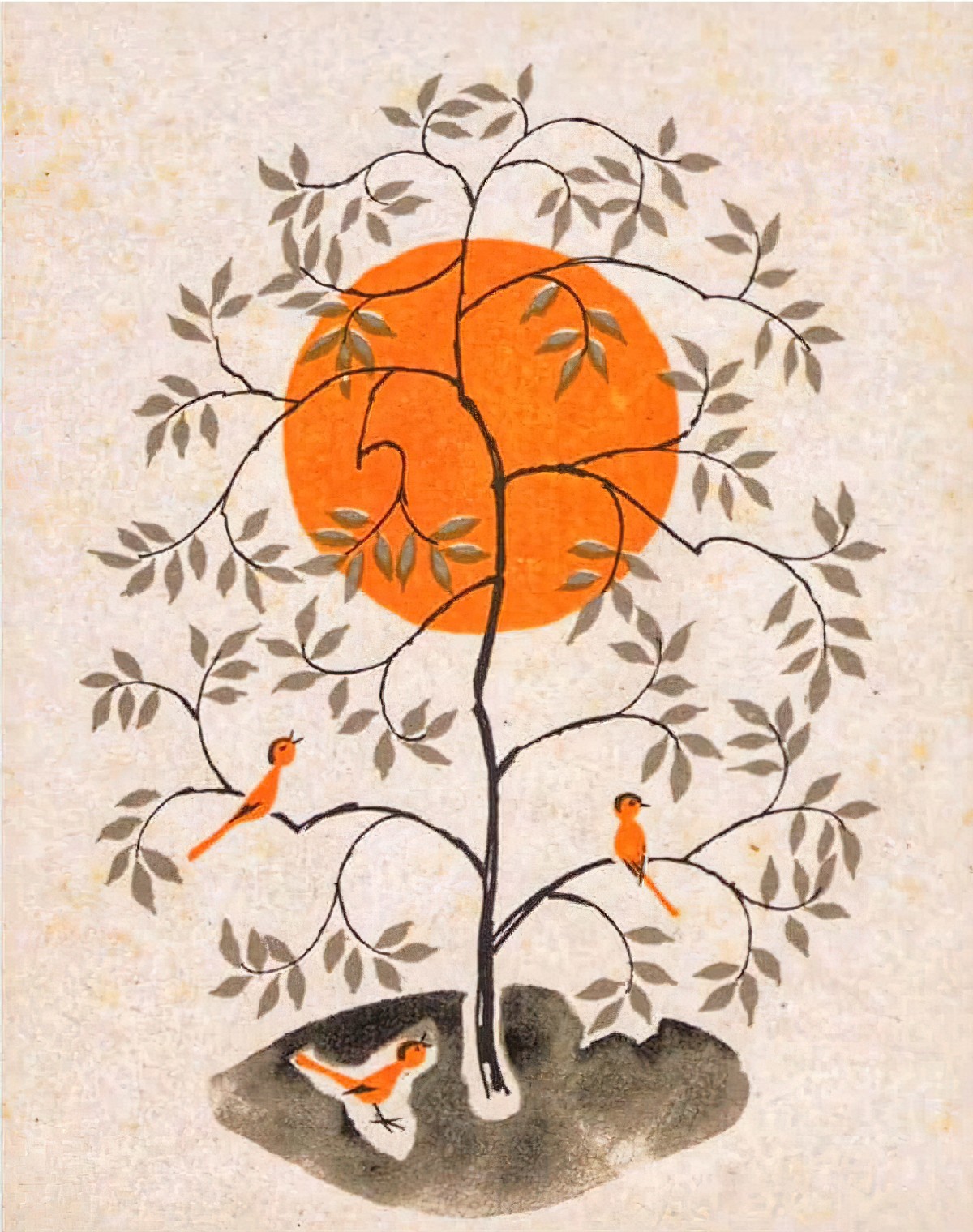

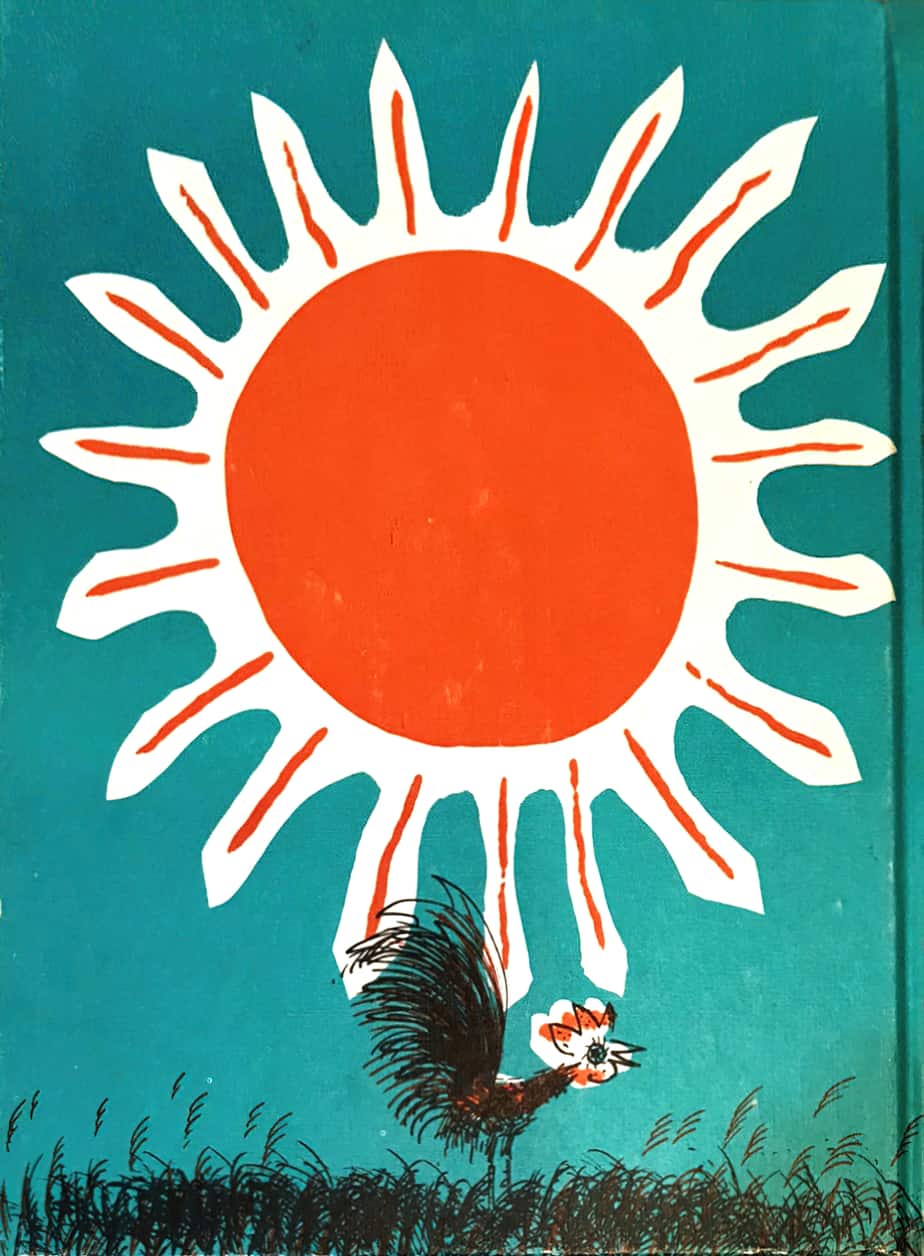

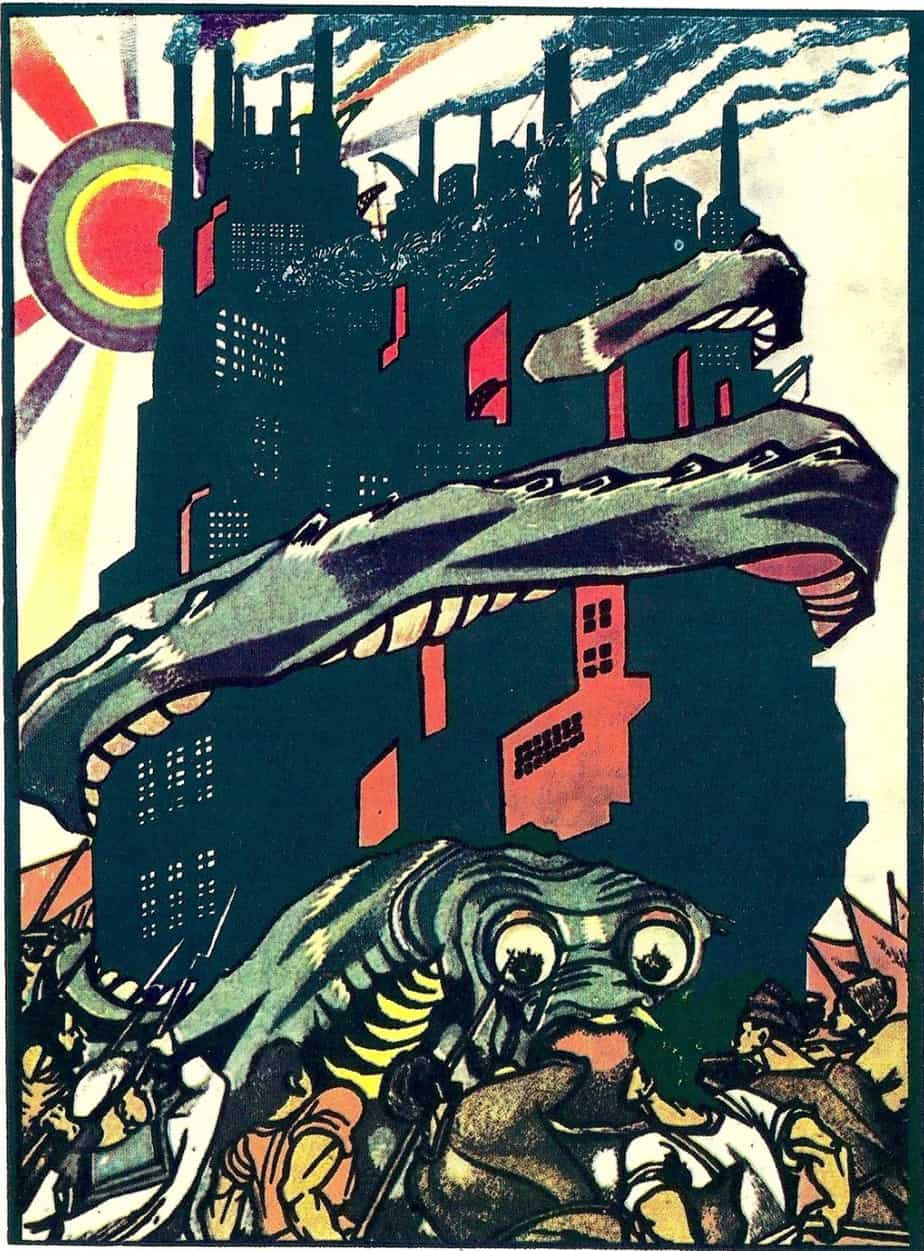

The sun in A Sound of Taiyoo Organ is very similar to the sun as depicted in this Russian picture book.

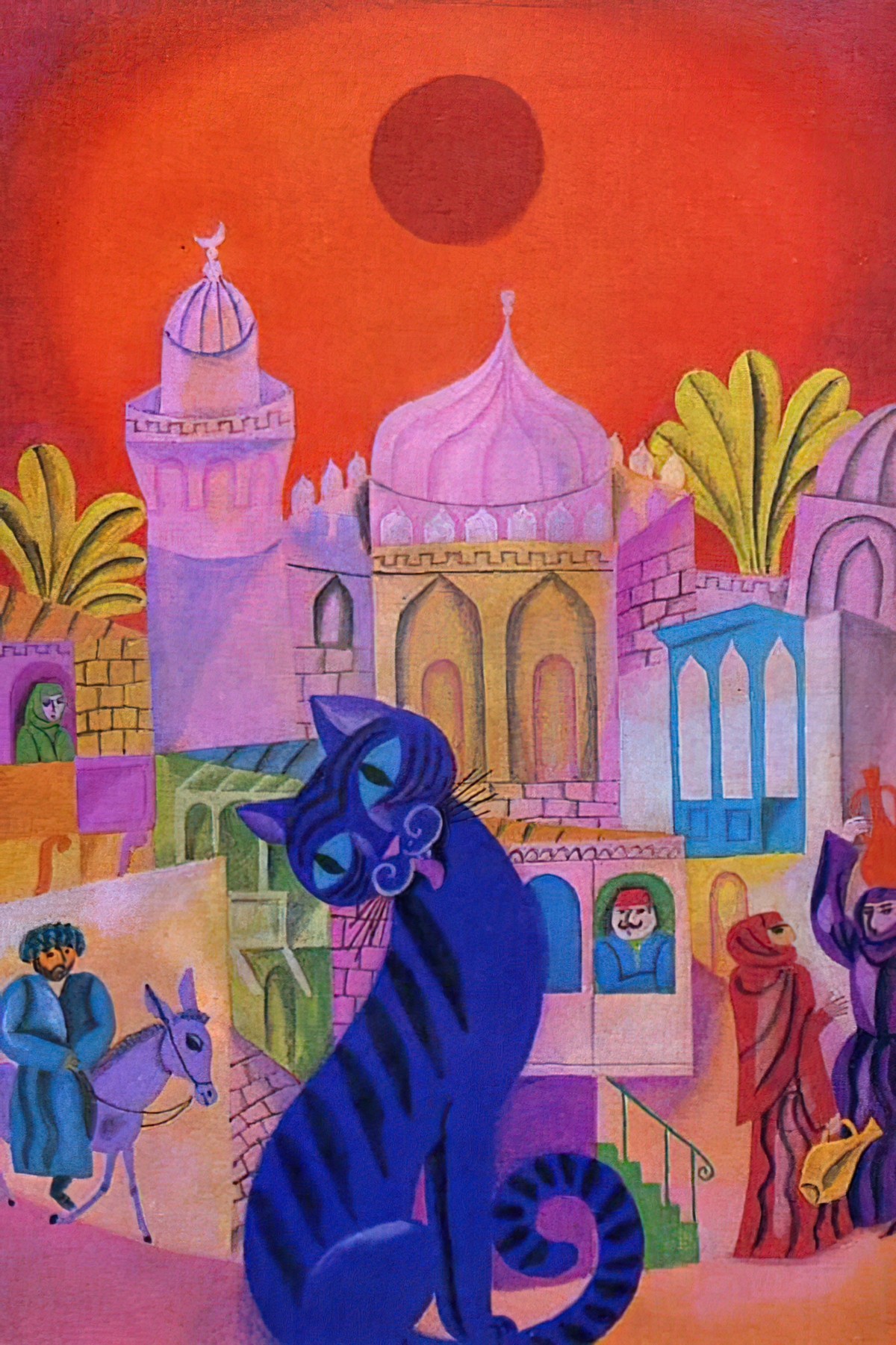

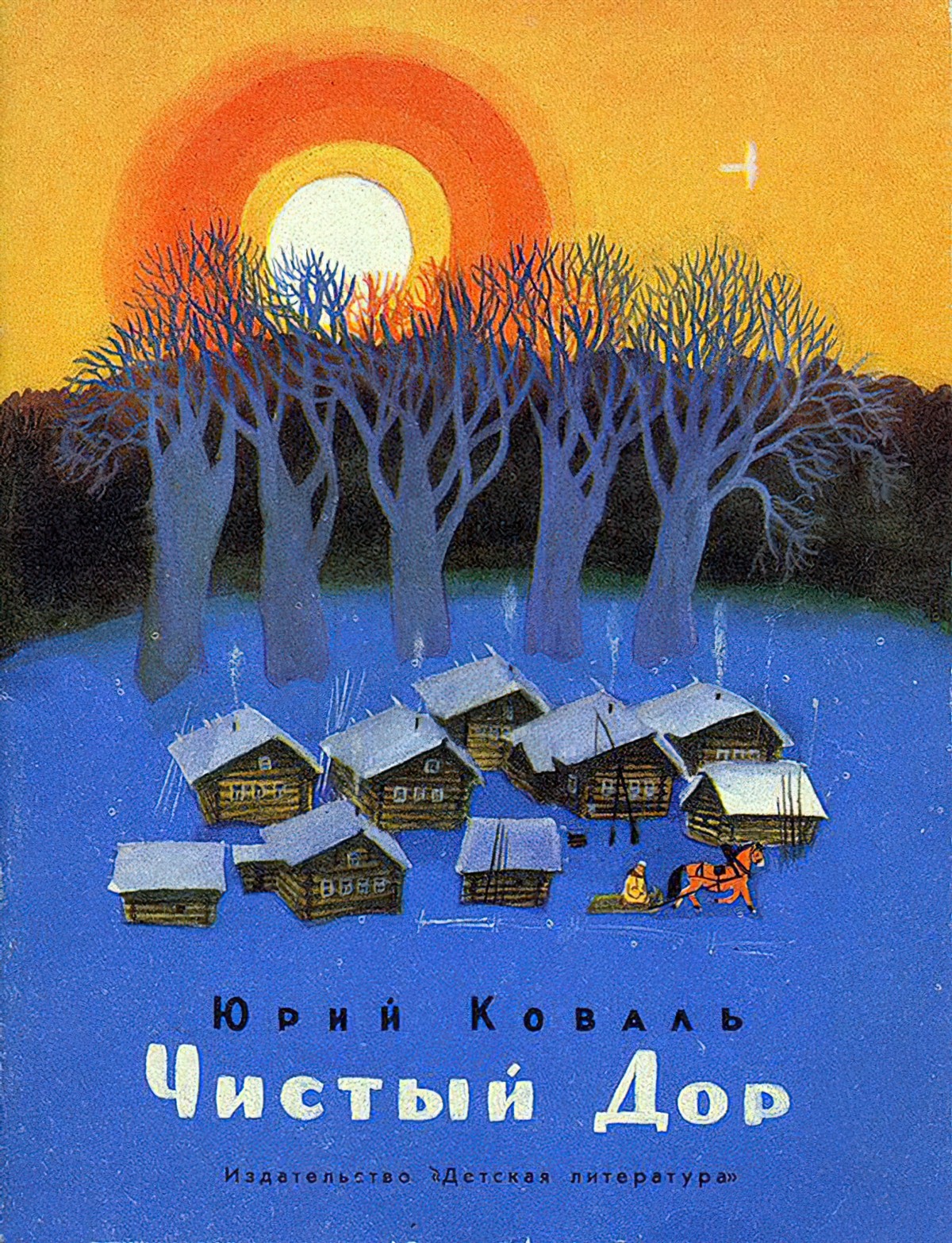

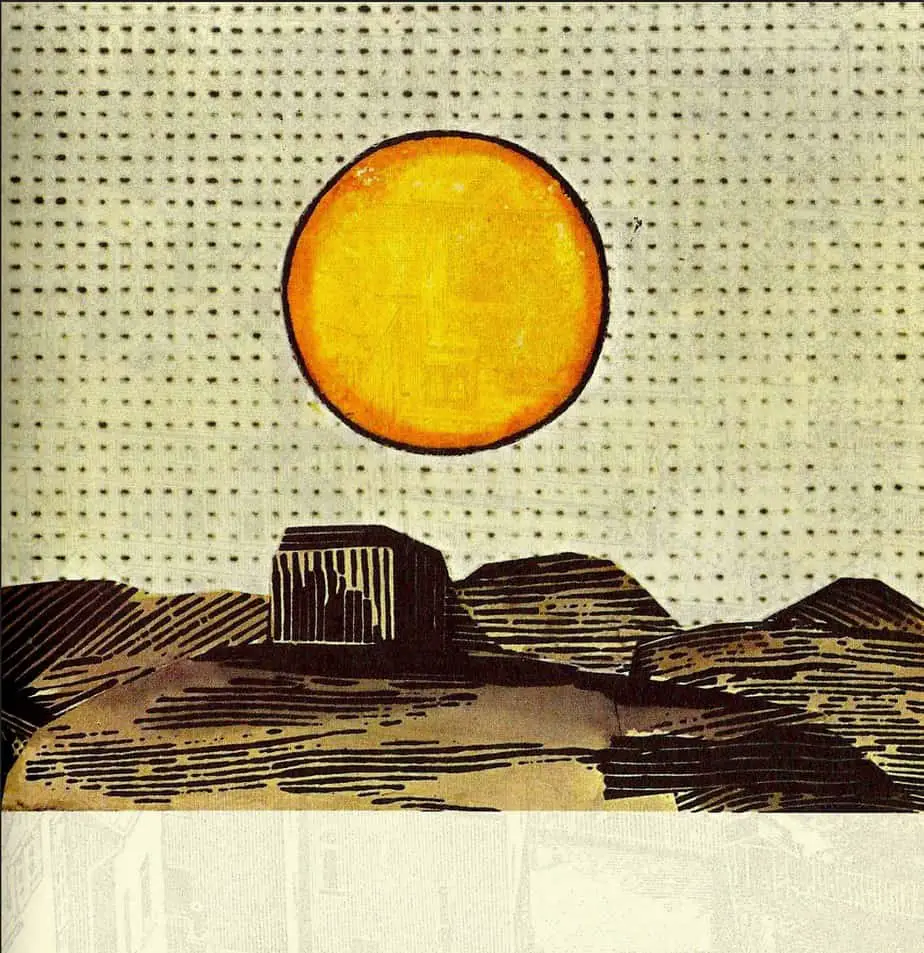

Below is another example of the sun as seen from Russia. I doubt it’s a coincidence that Japan and Russia are so geographically proximal. They’re so near to each other, in fact, that Russia and Japan are still in disagreements about which country gets to claim the territory of the Kuril Islands.

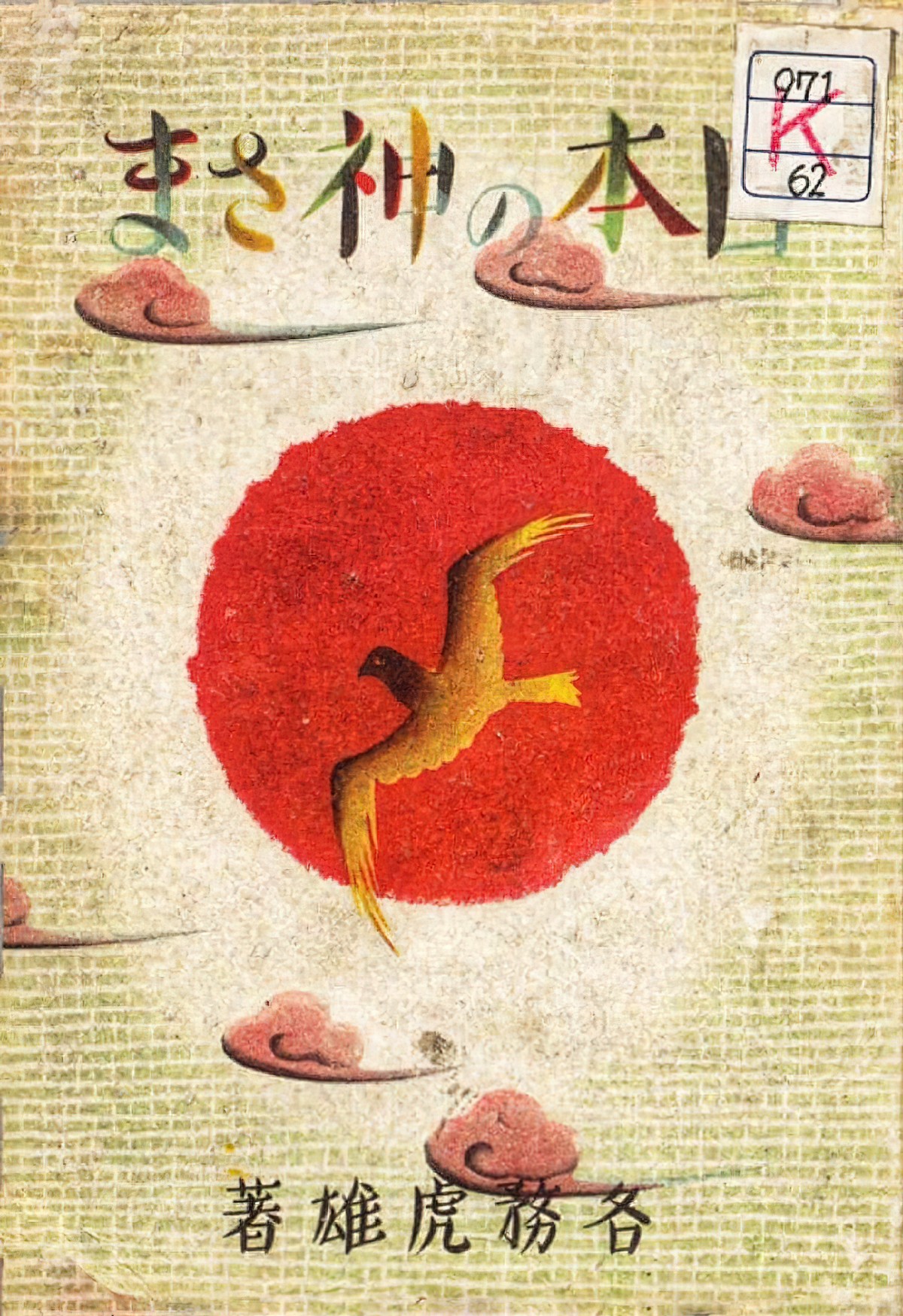

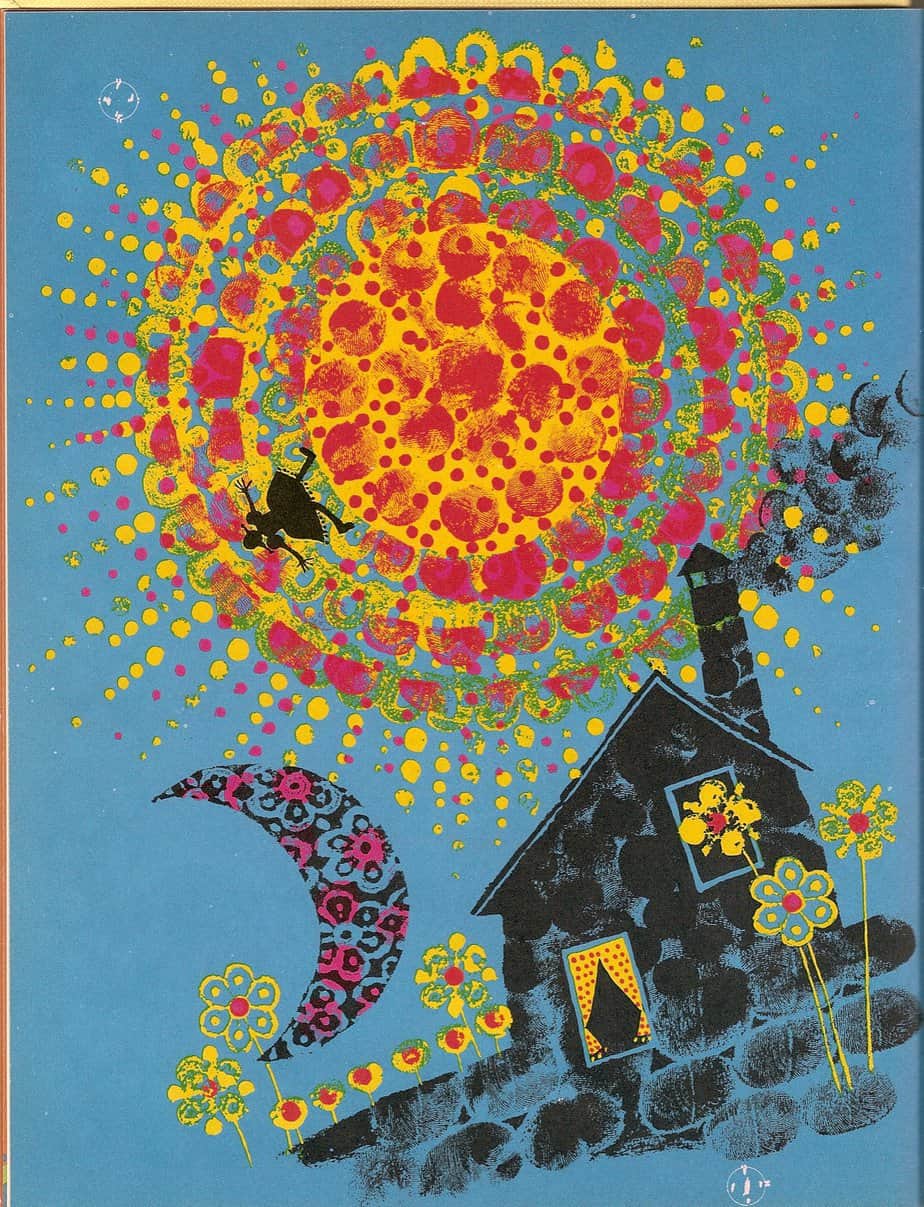

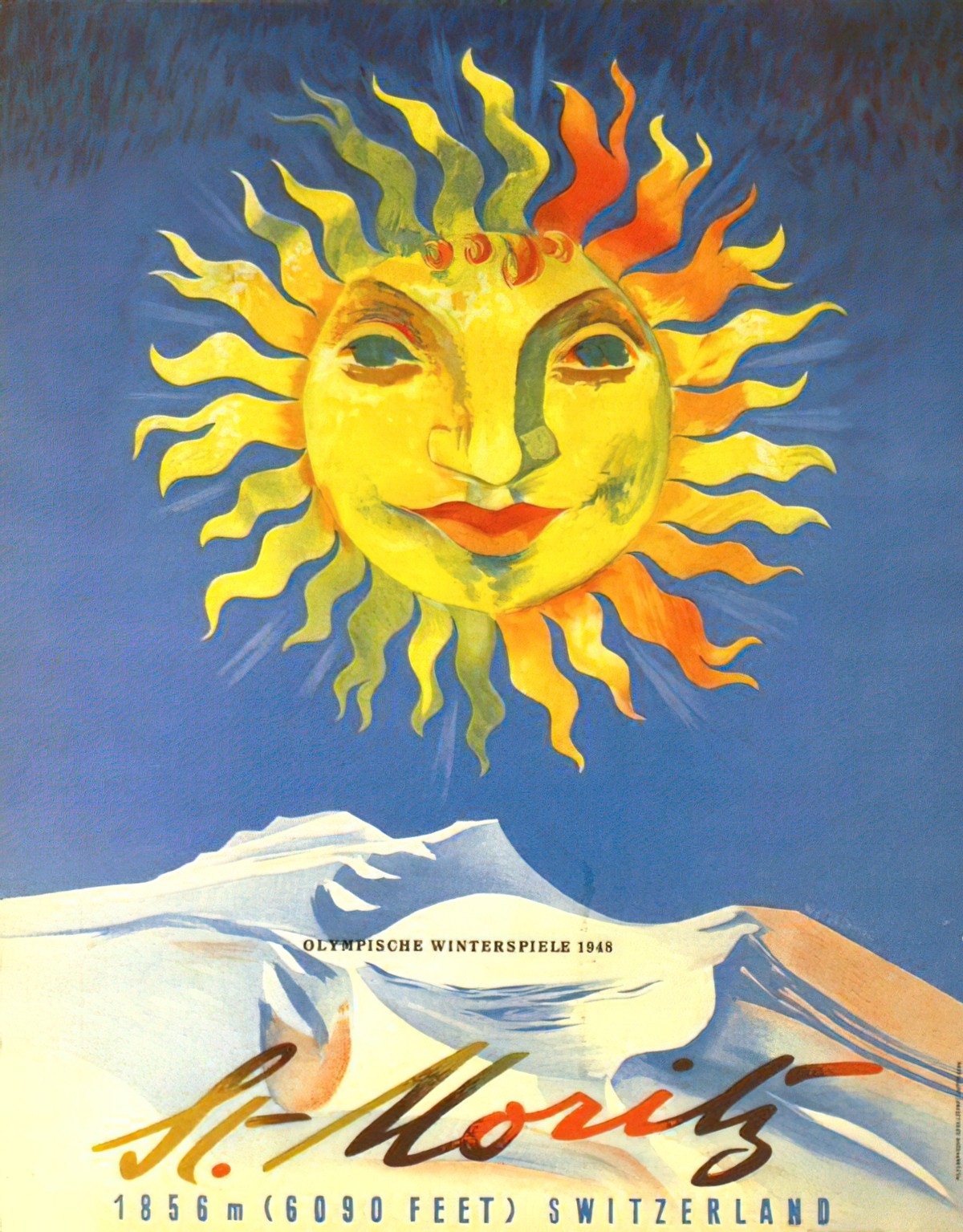

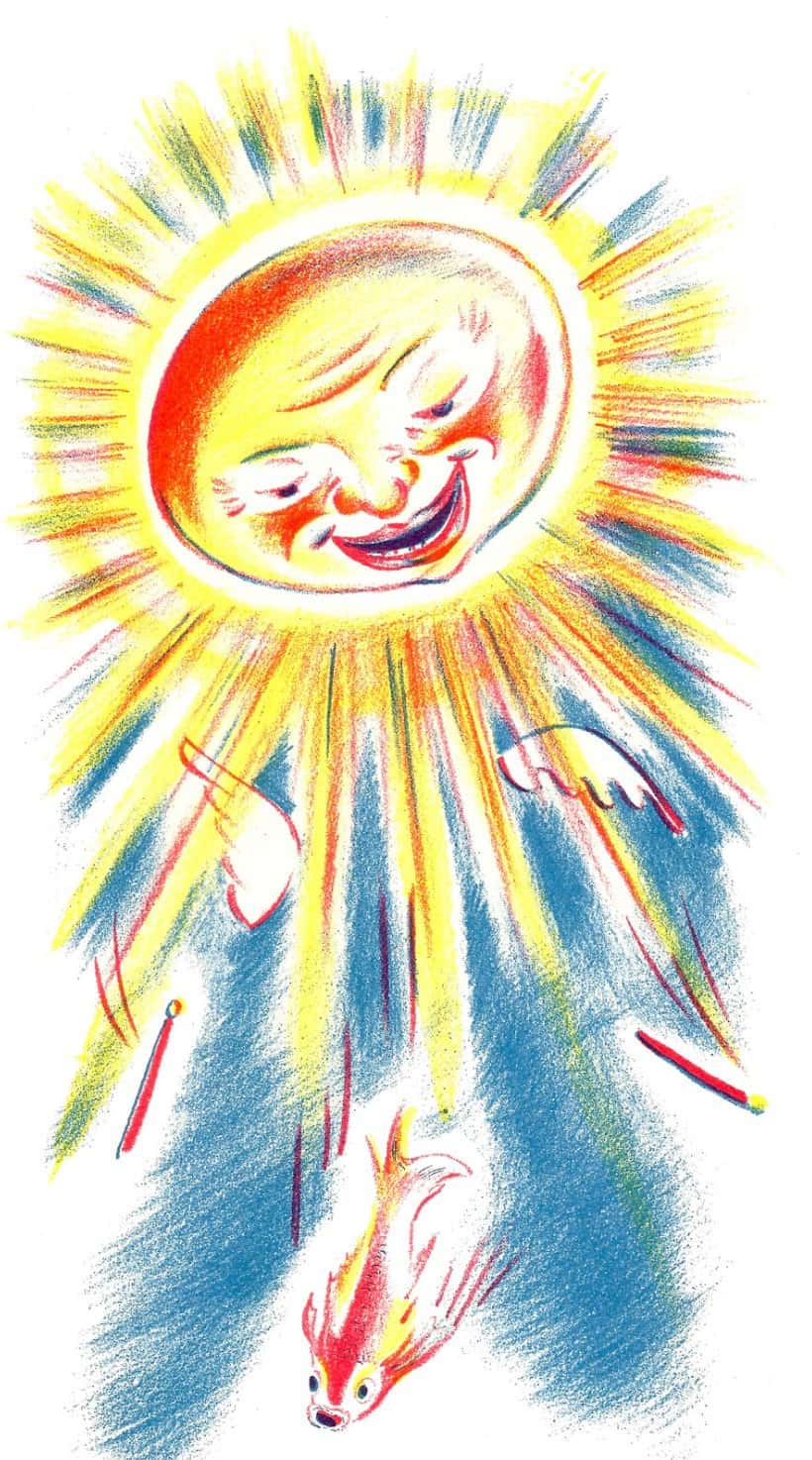

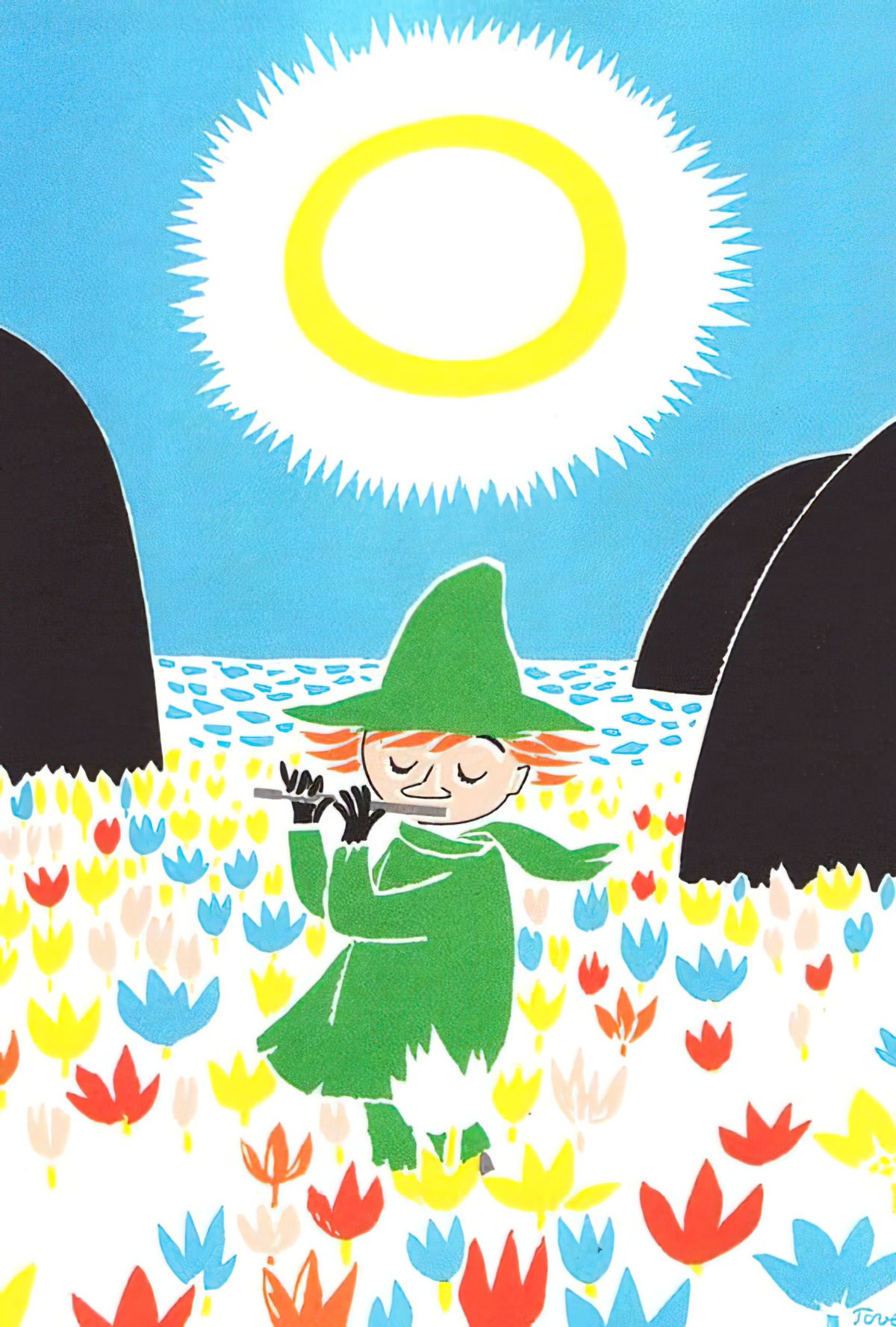

When taken to its extreme, a white sun surrounded by a corona of yellow with rays creates a powerful optical illusion for the viewer.

The sun looks quite different from Australia. When I lived in Japan I regularly left the house without sunglasses. Part of the reason is that sunglasses are considered a bit suspect by Japanese people, and a bit scary. But living here in Australia, I can’t leave the house at any time of year without sunglasses. I have a dark, wraparound pair for summer, and a lighter pair of lenses for winter. Australia and New Zealand share this in common; the sun is more glary down here. The archetypal storybook sun is yellow. But down under, the sun itself is white, and the sky around it is yellow. (Not that anyone should be looking directly at the sun.)

Maori language: Ata hāpara and atatū (dawn and just after sunrise). Ata mārie (good morning)

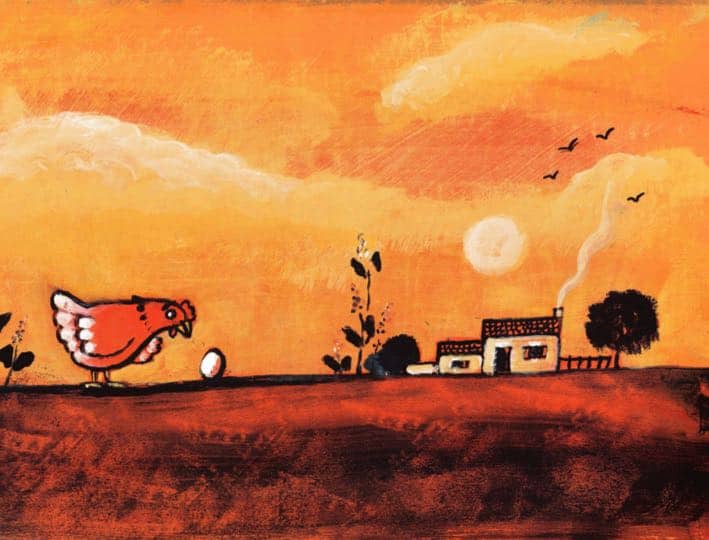

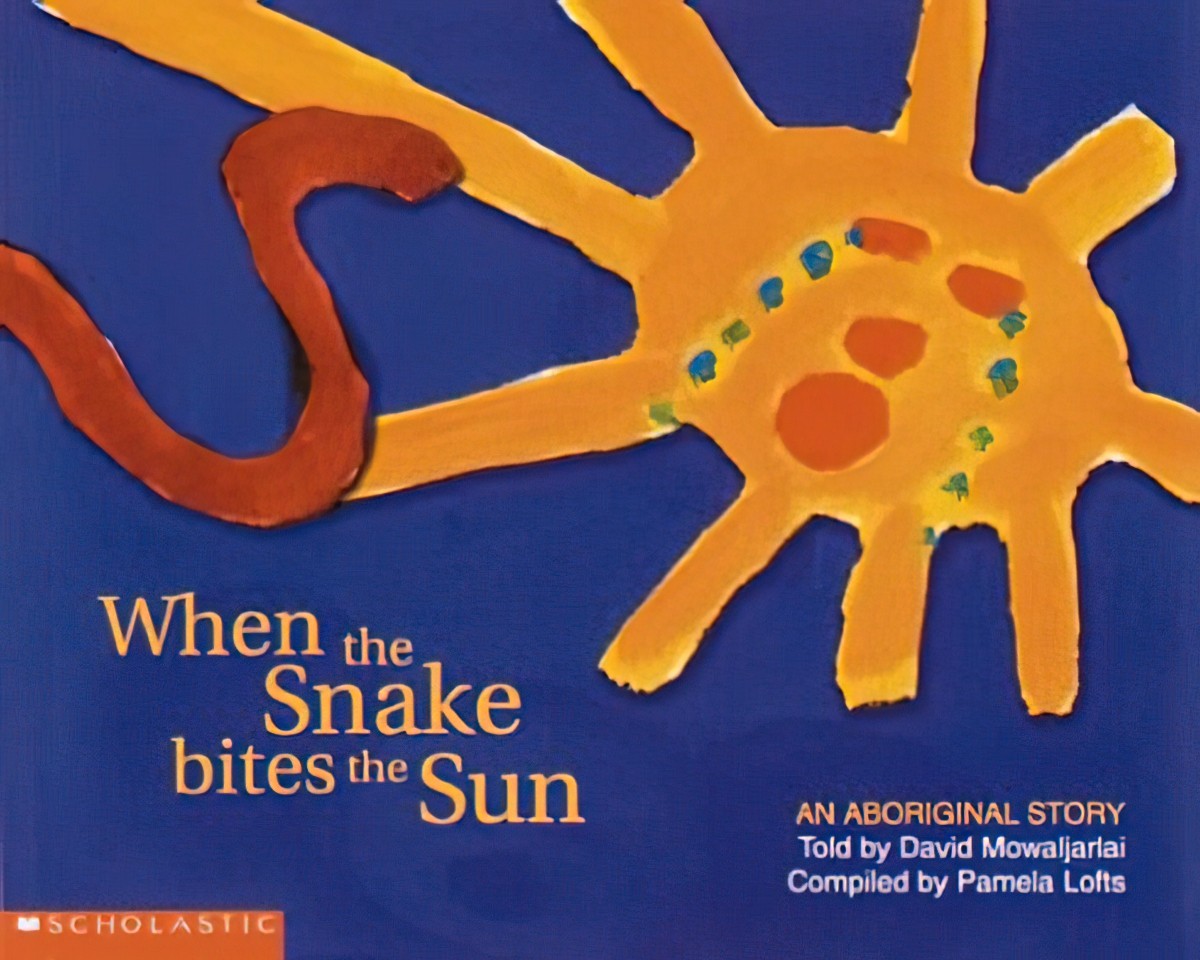

However, even in Australian art, sometimes you do see the archetypal storybook sun. The picture book below is Aboriginal. The sun is often covered in a yellow haze, especially in fire season.

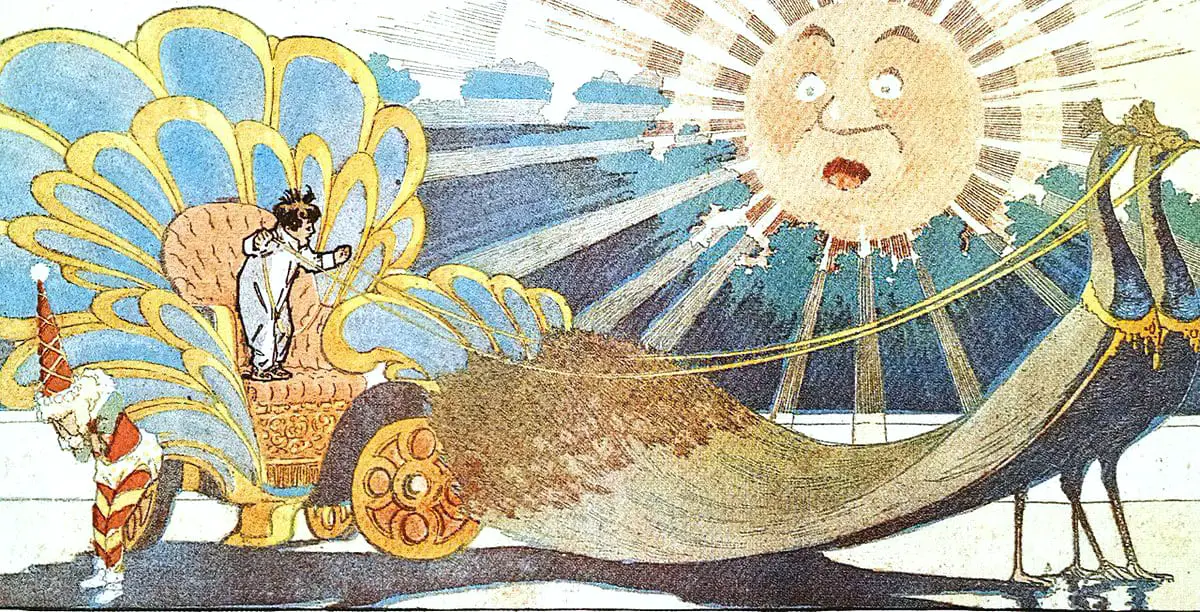

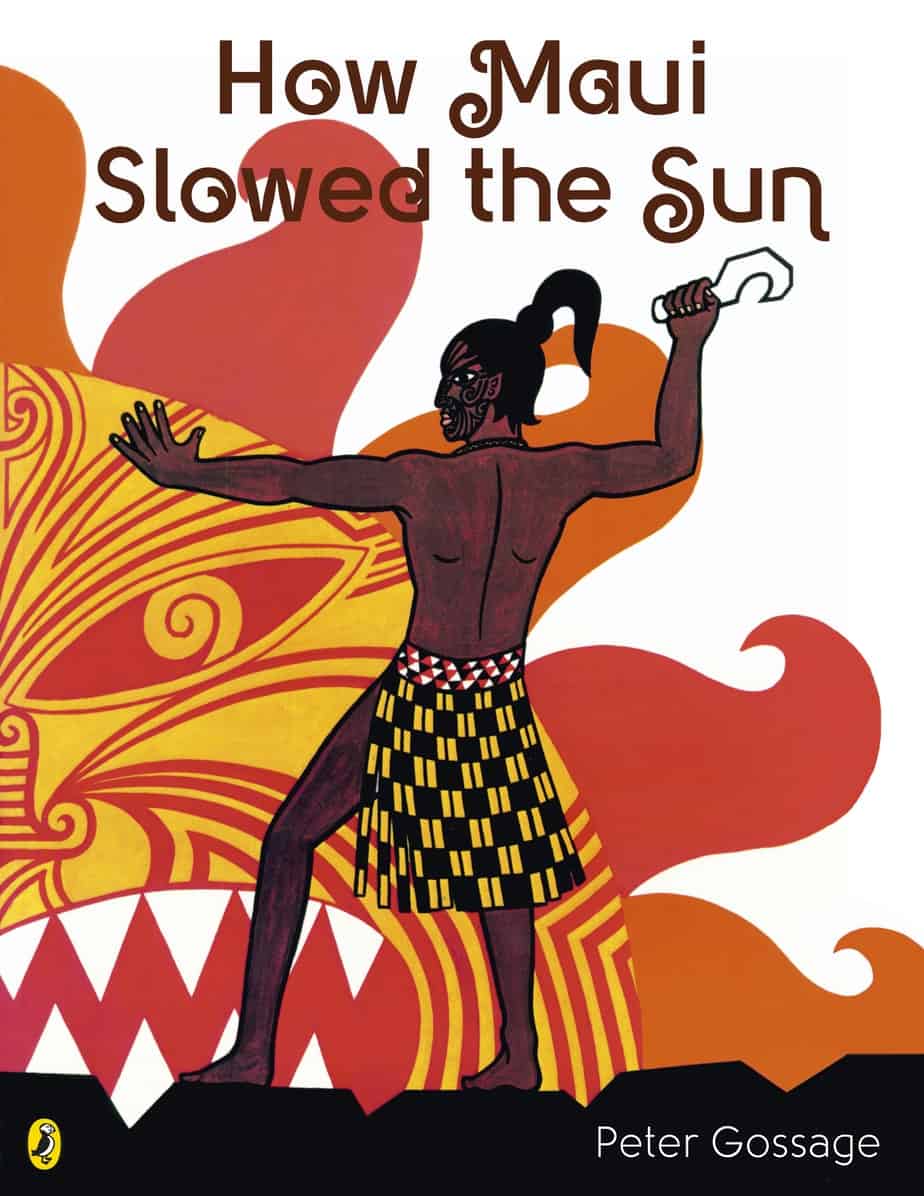

The picture book below is also a picture book mythology, this time from New Zealand. In this case, the sun itself is turned into a character. (The New Zealand sky turns orange when Australian bush fires are at their peak.)

Over the next twenty minutes the eastern cloud lifted a little, rolling up like a slow curtain. A strange, red glow crept out from under it, filling the sky with a clear, furious light against which the hilss with their spiky crowns were plastered flat and balck, having no more dimension than a shadow. The rolled edges of the clouds were touched with gold and rose colour, deepening second by second to an intense brightness.

A description of sunrise in The Tricksters, a 1980s YAL novel by New Zealand author Margaret Mahy

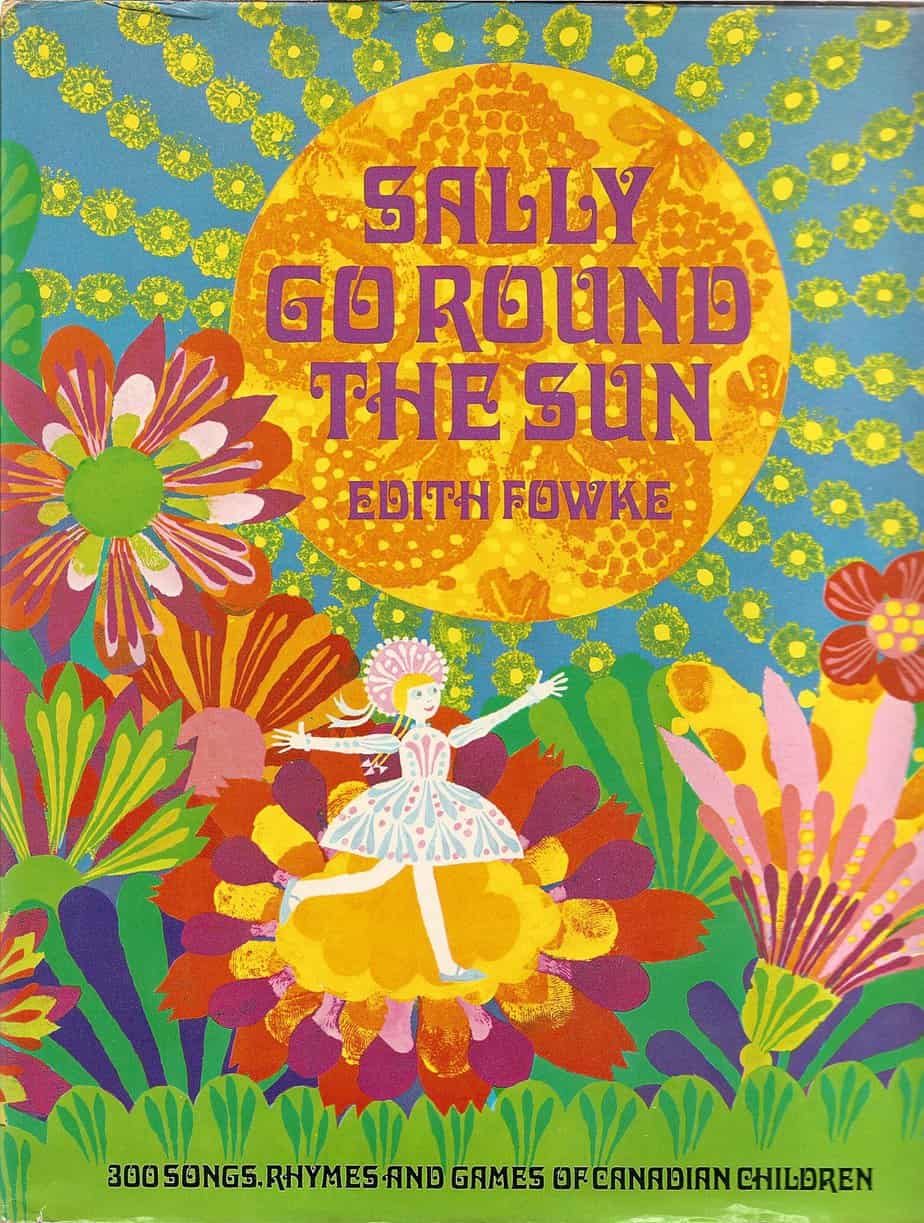

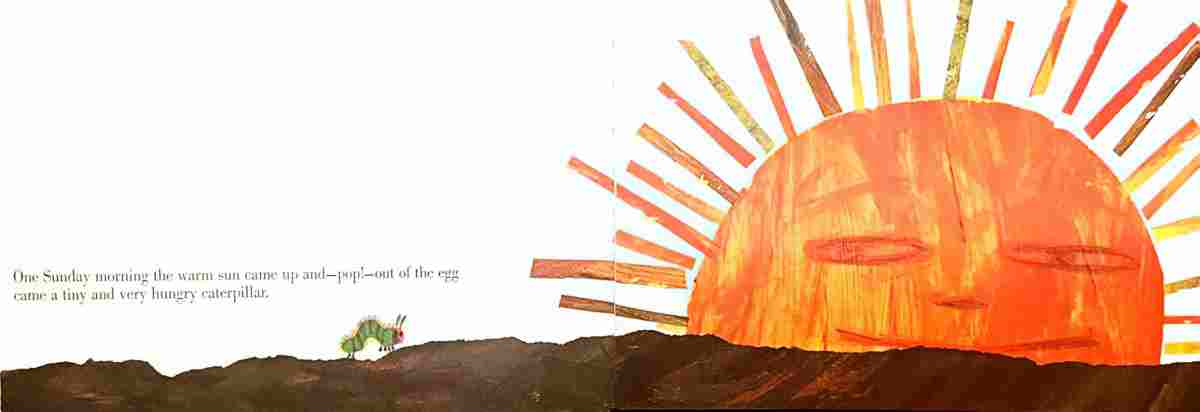

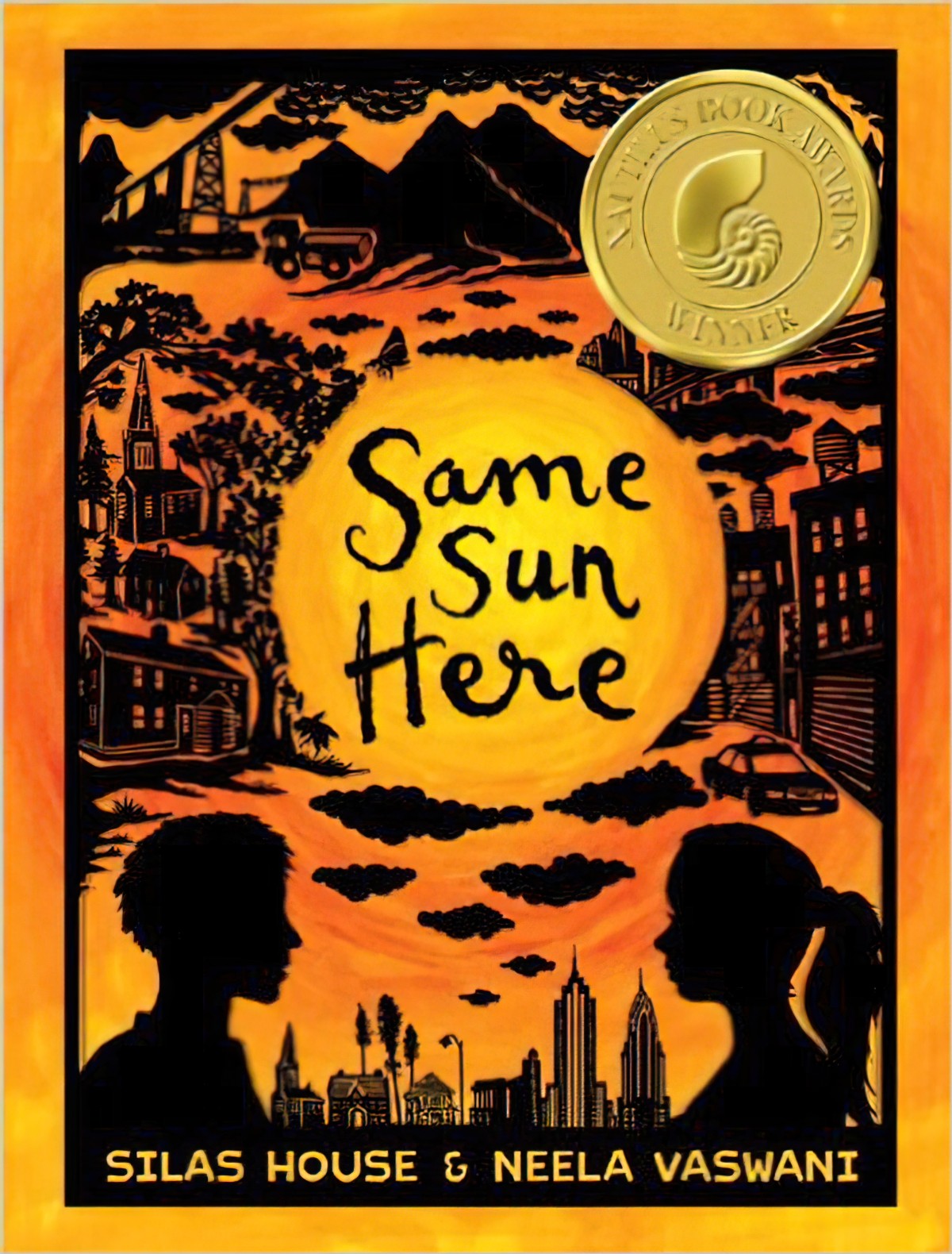

Yellow and orange suns are the default and we see them often in illustration. The children’s book below is about an Indian immigrant girl in New York City.

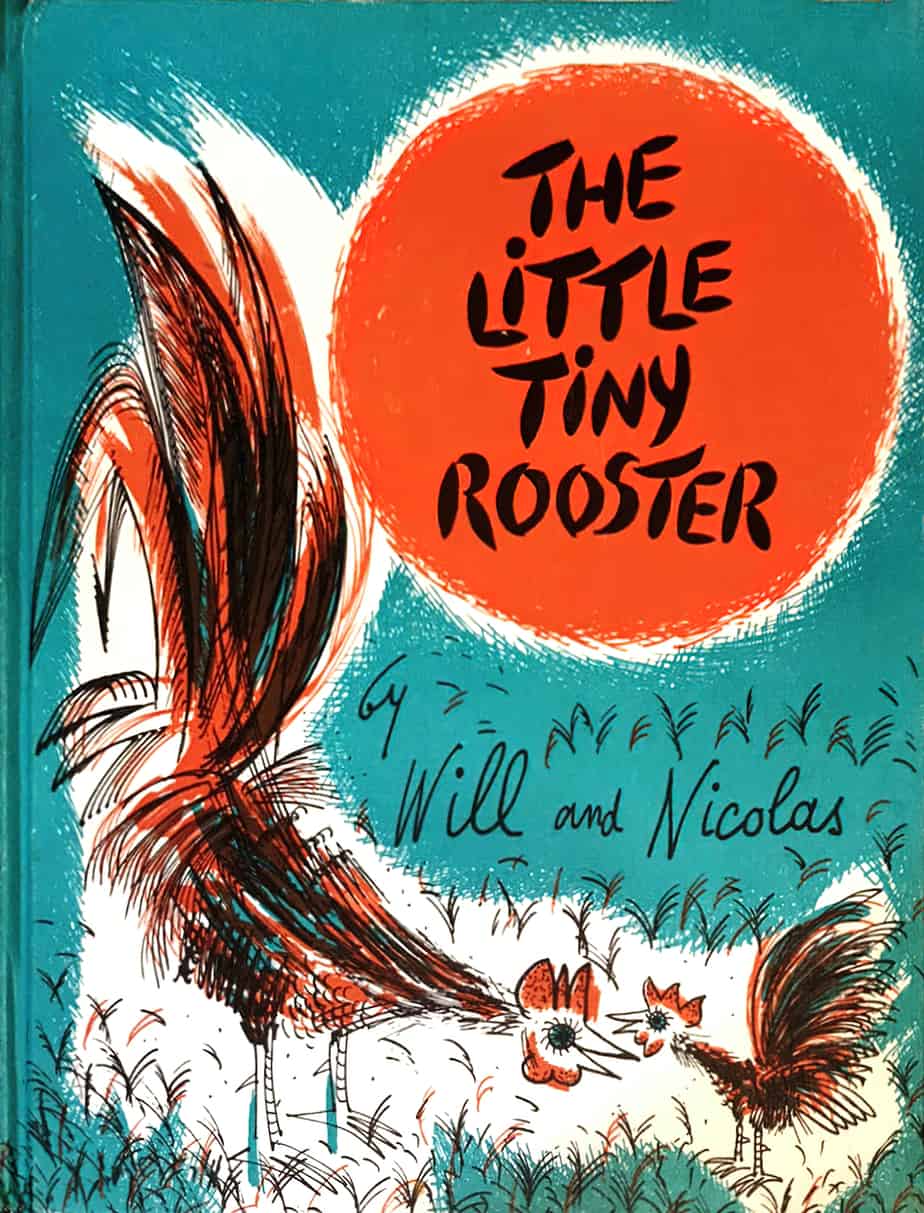

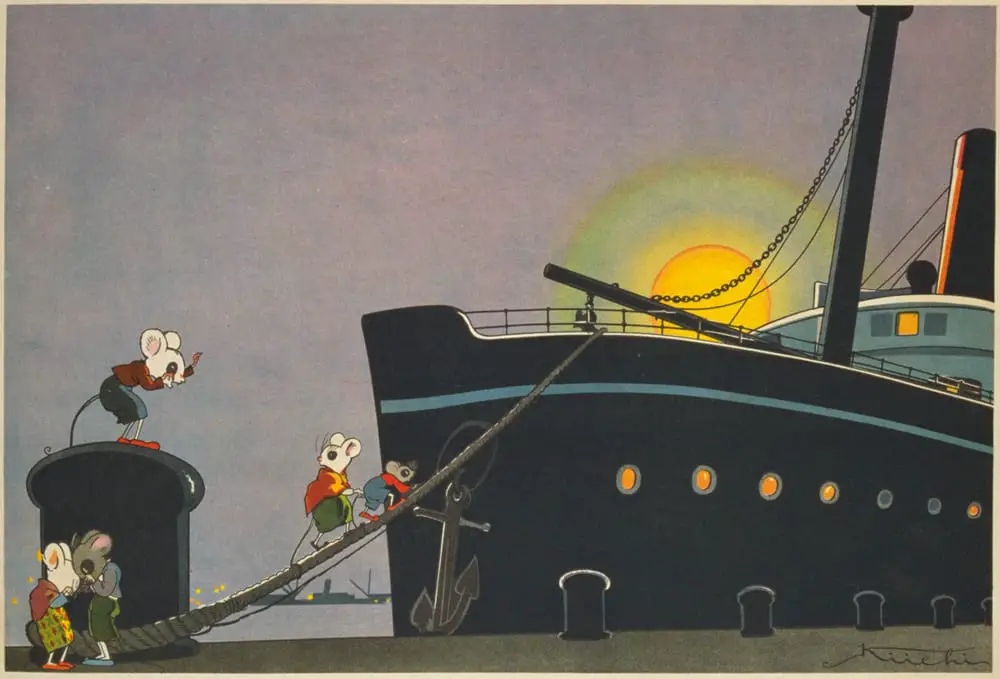

MADELINE IN LONDON BY LUDWIG BEMELMANS

Bemelmans is an interesting case, having grown up in Europe then emigrating to America as a young man. It’s safe to assume Bemelmans saw the sun through a number of different hazes. Generally, Bemelmans depicts the sun as yellow. For him, yellow is the ‘unmarked’ version. But he does something interesting with the sun in his picture book Madeline In London — after the horse tragically eats all the gardener’s flowers, the flower-loving gardener gets out of bed, opens the door and sees a yellow sun in the shape of a flower greeting him. But once he realises his flowerbed has been destroyed, Bemelmans paints the sun as red. In other words, Bemelmans uses red to signify a downward emotional turn.

Header illustration: by Polish illustrator Zdzisław Witwicki, (1921-2019).